SEMIOPUNK (30)

By:

February 1, 2025

An irregular, ongoing series of posts dedicated to surfacing examples (and predecessors) of the sf subgenre that HILOBROW was the first to name “semiopunk.”

BABEL (2022) | BABEL-17 (1966) | CAMP CONCENTRATION (1968) | A CANTICLE FOR LEIBOWITZ (1959) | CAT’S CRADLE (1963) | COSMONAUT KEEP (2000) | THE DIFFERENT GIRL (2013) | DOOM PATROL (1987–91) | THE EINSTEIN INTERSECTION (1967) | EMBASSYTOWN (2011) | ENGINE SUMMER (1979) | EXPLOITS AND OPINIONS OF DR. FAUSTROLL, PATAPHYSICIAN (1911) | FEERSUM ENDJINN (1994) | FLATLAND (1884) | FRIDAY (1982) | LE GARAGE HERMÉTIQUE (1976–79) | THE GLASS BEAD GAME (1943) | GLASSHOUSE (2006) | GRAVITY’S RAINBOW (1973) | THE HAMPDENSHIRE WONDER (1911) | LORD OF LIGHT (1967) | THE MAN WITH SIX SENSES (1927) | THE MOUNTAIN IN THE SEA (2022) | NINEFOX GAMBIT (2016) | ODD JOHN (1935) | PATTERN RECOGNITION (2003) | THE PLAYER OF GAMES (1988) | RIDDLEY WALKER (1980) | RODERICK (1980–83) | SNOW CRASH (1992) | THE SOFT MACHINE (1961) | SOLARIS (1961) | THE SPACE MERCHANTS (1953) | THE THREE STIGMATA OF PALMER ELDRITCH (1964) | TIME OUT OF JOINT (1959) | UBIK (1969) | VALIS (1981) | A VOYAGE TO ARCTURUS (1920) | VURT (1993) | WHITE NOISE (1985).

LORD OF LIGHT

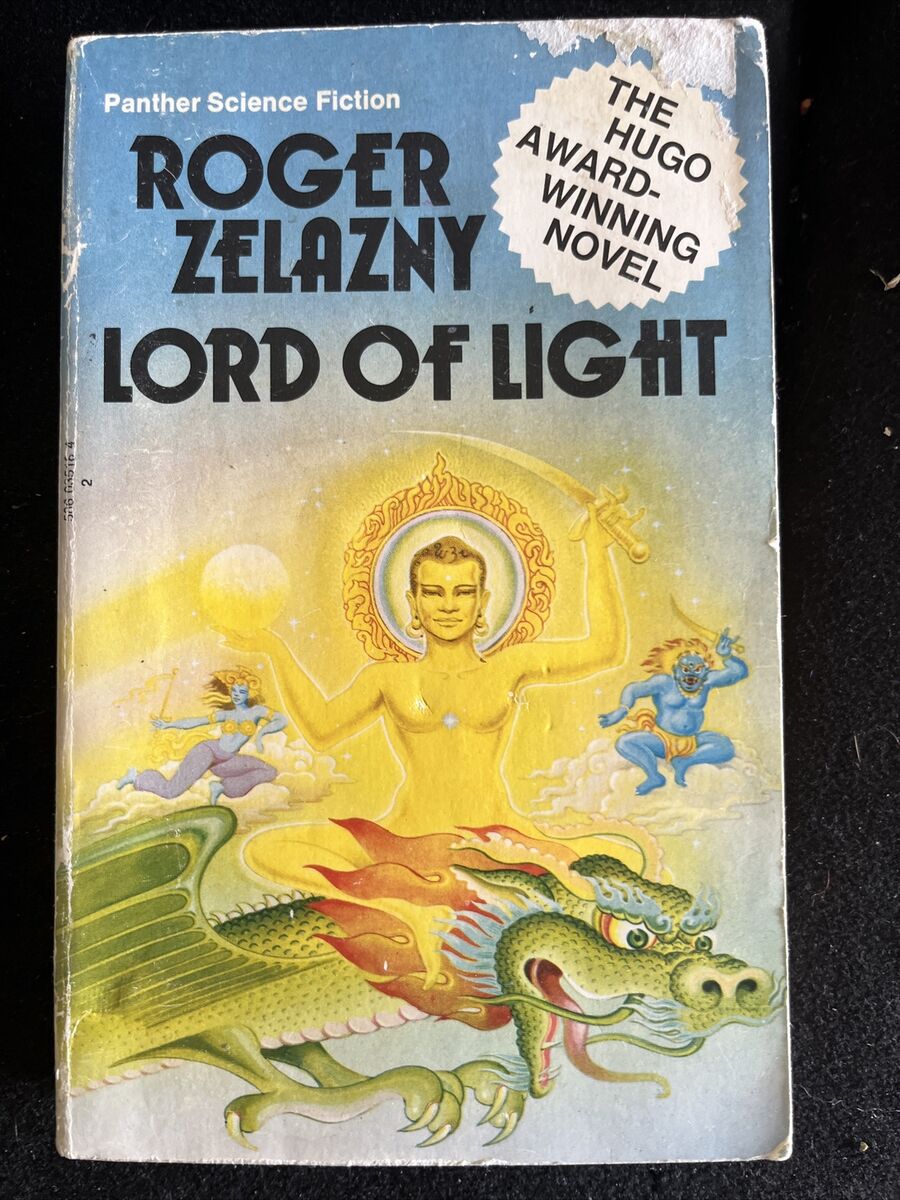

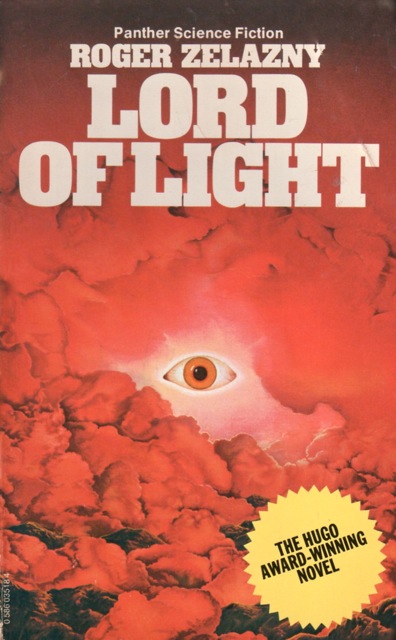

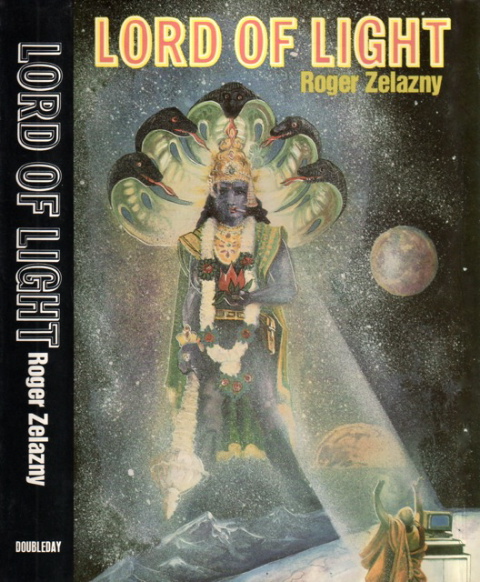

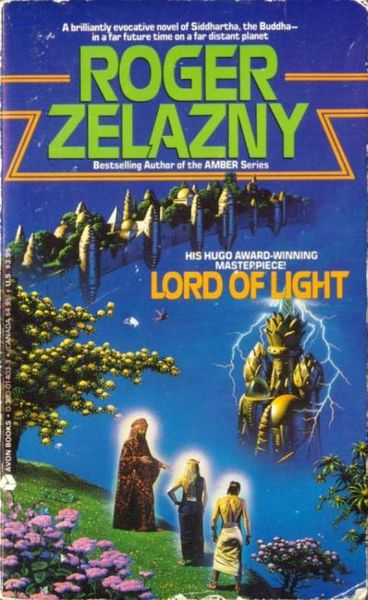

Roger Zelazny’s Lord of Light (1967), which won the Hugo for Best Novel, is one of the many sf titles that I’d first encounter via the Science Fiction Book Club, c. 1984 or so, when I was a teenager.

It’s a perplexing story, at first — because it seems to be a fantasy novel whose characters are Hindu gods. As the action commences, we find Yama (Hindu god of death and dharma), collaborating with fellow Celestial City outcasts Ratri (goddess of night) and a talking ape named Tak to surreptitiously restore Mahasamatman — he prefers “Sam” — to corporeal reality. Sam, it seems, was vanquished — after having tried and failed to overthrow the ruling pantheon of gods — to the sky-cloud of Nirvana. All of which reminds me, now, of Iain M. Banks and his digital versions of Heaven and Hell; also reminiscent of Banks is the fact that Lord of Light begins with a flash-forward. Once Sam’s consciousness has been downloaded into a flesh-and-blood body, the narrative reverts to a (much) earlier period during which Sam abandoned his godly name and form and took on the mortal aspect of Siddhartha — in order to introduce teachings that would undermine the doctrine of obedience to the gods among the world’s mortals.

Eventually, we figure out that we’re reading science fiction. One of the tip-offs: The gods smoke cigarettes and punctuate their epic-style language with American slang and pop culture references. Yama tends a “pray-machine” that offers “many kilowatts of prayer.” It turns out that we’re on a planet colonized long ago by (mostly South Asian) humans from Earth. The officers of the space ark have deployed advanced technology to make themselves immortal — by transferring their consciousness from one body to another. Over vast stretches of time, the “Firsts” have developed mutant superpowers related to their initial areas of expertise. They’ve set themselves up as Hindu gods, ruling over the non-immortal descendants of the ark’s other passengers. Whenever a mere mortal dies, the “gods” decide whether or not to reincarnate them into a higher caste… or into an animal’s body instead. The decisions are based on the subject’s fealty to the gods.

Sam, we learn, was one of the original gods. His contribution to their ascendancy, early on, involved his mental control of electromagnetics. (Note that the Marvel character Magneto had appeared a few years earlier, in The X-Men #1.) In his role as one of the Firsts, Sam helped destroy or bind the planet’s natives — beings of pure energy — now known as demons. The gods then decided to suppress enlightenment among the planet’s mortal population — including technological advances. Which leads Sam, a technologist, to have a change of heart about the whole scheme. After some centuries, Sam liberates some of his old power-boosting gadgetry from a Celestial City museum, and descends into a place called Hellmouth to enlist the aid of the bound energy-demons. Although taken captive and “killed,” he returns and leads an army of demons, humans, and rebel gods in a (failed) revolution against the pantheon of Celestial City. Along the way Yama, who begins as Sam’s enemy, becomes his closest friend and secret ally.

All of this occurs over a vast span of time; the story is epic. Catching up, at last, to the future point at which our story began, Sam and his allies plan their next move in their campaign against the ruling pantheon.

Writing for HILOBROW in 2013, Gordon Dahlquist described Lord of Light as a book”dedicated to dragging all wizards out from behind their curtains.” This unveiling/demystifing aspect of the book is what I imagine my fellow semioticians would find most appealing about it. Everything that we hold sacred — those aspects of our social and cultural order that seem natural, eternal (immortal, even), and inevitable — are in fact human constructs. Zelazny dramatizes this wise message in a rich way.

The aspect of Hinduism that I’ve always found astonishing is this: Hindus believe in one ultimate reality (Brahman), and avatars (or incarnations, when they take on flesh-and-blood form) are understood as different forms of this supreme being. The Hindu pantheon of “gods” are not considered separate gods in their own right; they are useful illusions generated in order to give mortals an object lesson in restoring Dharma. There’s a parallel between this religious tradition and semiotics, which understands each “node” in a network of meaning to be merely a symbol or metaphor for some underlying, impossible-to-represent meaning. There are moments in Zelazny’s book where this sort of Hindu/semiotic insight is articulated.

For example, when Sam first returns to bodily form, he preaches a lesson to the monks of Yama’s temple, in order to call forth within them “nobler sentiments and higher qualities of spirit” and defeat the false gods’ “machineries of Karma” – at least for a while. Sam tells the monks:

“Names are not important […]. To speak is to name names, but to speak is not important. A thing happens once that has never happened before. Seeing it, a man looks upon reality. He cannot tell others what he has seen. Others wish to know, however, so they question him saying, ‘What is it like, this thing you have seen?’ So he tries to tell them. Perhaps he has seen the very first fire in the world. He tells them, ‘It is red, like a poppy, but through it dance other colors. It has no form, like water, flowing everywhere. It is warm, like the sun of summer, only warmer. It exists for a time upon a piece of wood, and then the wood is gone, as though it were eaten, leaving behind that which is black and can be sifted like sand. When the wood is gone, it too is gone.’ Therefore, the hearers must think reality is like a poppy, like water, like the sun, like that which eats and excretes. They think it is like to anything that they are told it is like by the man who has known it. But they have not looked upon fire. They cannot really know it. They can only know of it. But fire comes again into the world, many times. More men look upon fire. After a time, fire is as common as grass and clouds and the air they breathe. They see that, while it is like a poppy, it is not a poppy, while it is like water, it is not water, while it is like the sun, it is not the sun, and while it is like that which eats and passes wastes, it is not that which eats and passes wastes, but something different from each of these apart or all of these together. So they look upon this new thing and they make a new word to call it. They call it ‘fire.’ […] No word matters. But man forgets reality and remembers words.”

We need words! But we should also learn to tune into the flux upon which the meaning-structure that makes word-use possible is constructed. And having done so, we should seek to use words for beautiful purposes instead of ugly ones.

Does he believe in his own sermon? Yama laters asks. “I’m very gullible when it comes to my own words,” Sam replies. “I believe everything I say, though I know I’m a liar.”

Fun facts: In 1979 it was announced that Lord of Light would be adapted into a big-budget science fiction movie. A massive set was going to be constructed in Aurora, Colorado — and after the movie, it would become a sci-f theme park. Jack Kirby himself was hired to contribute costume and set design sketches. (The whole project turned out to be a scam.) During the 1979–81 Iranian hostage crisis, when members of the US diplomatic staff were trapped in Tehran, the CIA acquired the abandoned movie’s script and Kirby’s designs — and used them to create a cover story for the escapees. As depicted in the 2012 movie Argo.

JOSH GLENN’S *BEST ADVENTURES* LISTS: BEST 250 ADVENTURES OF THE 20TH CENTURY | 100 BEST OUGHTS ADVENTURES | 100 BEST RADIUM AGE (PROTO-)SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST TEENS ADVENTURES | 100 BEST TWENTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST THIRTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST GOLDEN AGE SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST FORTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST FIFTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST SIXTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST NEW WAVE SCI FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST SEVENTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST EIGHTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST DIAMOND AGE SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST NINETIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST HADRON AGE SCI-FI ADVENTURES.