SEMIOPUNK (29)

By:

January 4, 2025

An irregular, ongoing series of posts dedicated to surfacing examples (and predecessors) of the sf subgenre that HILOBROW was the first to name “semiopunk.”

BABEL (2022) | BABEL-17 (1966) | CAMP CONCENTRATION (1968) | A CANTICLE FOR LEIBOWITZ (1959) | CAT’S CRADLE (1963) | COSMONAUT KEEP (2000) | THE DIFFERENT GIRL (2013) | DOOM PATROL (1987–91) | THE EINSTEIN INTERSECTION (1967) | EMBASSYTOWN (2011) | ENGINE SUMMER (1979) | EXPLOITS AND OPINIONS OF DR. FAUSTROLL, PATAPHYSICIAN (1911) | FEERSUM ENDJINN (1994) | FLATLAND (1884) | FRIDAY (1982) | LE GARAGE HERMÉTIQUE (1976–79) | THE GLASS BEAD GAME (1943) | GLASSHOUSE (2006) | GRAVITY’S RAINBOW (1973) | THE HAMPDENSHIRE WONDER (1911) | LORD OF LIGHT (1967) | THE MAN WITH SIX SENSES (1927) | THE MOUNTAIN IN THE SEA (2022) | NINEFOX GAMBIT (2016) | ODD JOHN (1935) | PATTERN RECOGNITION (2003) | THE PLAYER OF GAMES (1988) | RIDDLEY WALKER (1980) | RODERICK (1980–83) | SNOW CRASH (1992) | THE SOFT MACHINE (1961) | SOLARIS (1961) | THE SPACE MERCHANTS (1953) | THE THREE STIGMATA OF PALMER ELDRITCH (1964) | TIME OUT OF JOINT (1959) | UBIK (1969) | VALIS (1981) | A VOYAGE TO ARCTURUS (1920) | VURT (1993) | WHITE NOISE (1985).

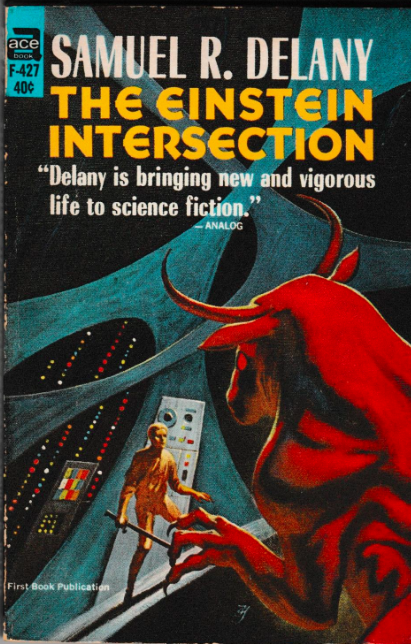

THE EINSTEIN INTERSECTION

The Einstein Intersection was published in 1967, when Samuel R. Delany was just 22. Although this extraordinary, if often puzzling and even infuriating book had detractors at the time, it was awarded the Nebula Award for Best Science Fiction Book. However, James Blish, a celebrated member of the so-called Golden Age (c. 1934–63, in my periodization scheme) cohort of sf authors, showed up at the awards banquet, Delany would recall, to gripe about the “pretentious literary nonsense” that had of late begun to infect science fiction. Delany was obviously doing something right.

Some 40,000 years from now, humankind has evolved beyond any need for their bodies, their culture and traditions, their artifacts, and so forth — so they’ve transcended the mortal plane, left the Earth and humankind’s traditions behind. Our protagonist, Lo Lobey, a 23-year-old, brown-skinned, satyr-like musician, will discover that he is a member of an alien race who’s arrived on Earth and inherited humankind’s norms and forms without properly vetting them first. Which is probably what it felt like to be a queer, Black 22-year-old in 1967.

The mixed-up mythos inhabited by Lobey’s species incorporates everything from Roman and Greek mythology to American yarns about the Wild West and even the Beatles — figured here as semi-legendary keepers of “the great rock and the great roll.” *

Lobey’s journey of understanding begins when his mate, La Friza, dies. (This alien species is three-gendered; their pronouns are “lo,” “la,” and “le.”) Like the mythical musician Orpheus, whose myth — among others — he is unwittingly recapitulating, Lobey sets off to see if he can’t perhaps restore his beloved to life. Along the way, he’ll discover an even more important mission: His species must come to an understanding of its true (i.e., fluid) nature, and develop new and improved (i.e., highly flexible) ways of living together rather than merely aping traditions inherited from the past. Or something like that; that’s how I understand the story, anyway.

The appeal to semioticians ought to be immediately obvious. All of us inhabit a cultural system whose lineaments are invisible, inherited, and seemingly natural and inevitable. Our perceptions are warped by this system, our values and decisions influenced by it, our actions to some extent guided by it. We’ve inherited it, but we don’t entirely understand it, nor do we recognize how un-free we are because we can’t “see” it. We’re mutable, fluid creatures restricted and restrained by the inherited cultural frameworks analyzed by semioticians….

___

* In Michael Moorcock’s four Runestaff fantasy/sf novels, we read that the ancient gods of “Granbretan” are Jhone, Jhorg, Phowl, and Rhunga. Great minds think alike. I dig it that another of Moorcock’s gods is “Jeajee Blad”: J.G. Ballard.

Along the way, Lobey will meet several excellent characters, including Spider, a badass evolved alien (“different,” as they’re known) who uses his telekinetic powers to herd dragons, and who becomes a kind of guide to Lobey; the sweet prince-in-exile Greeneye, a Christ-like “different” who performs miracles; Dove, a ubiquitous sex symbol; and Kid Death, the novel’s antagonist, a mocking, child-like, Billy the Kid-recapitulating “different” who murders mutants with his mind.

The book’s title is explained by Spider, who suggests that Einstein’s theory of relativity only became truly helpful to mankind once it intersected with Gödel’s incompleteness theorem, a “mathematically precise statement about the vaster realm beyond the limits Einstein had defined.” Spider expands on this intriguing notion like so:

In any closed mathematical system — you may read ‘the real world with its immutable laws of logic’ — there are an infinite number of true theorems — you may read ‘perceivable, measurable phenomena’ — which, though contained in the original system, can not be deduced from it — read ‘proven with ordinary or extraordinary logic.’ Which is to say, there are more things in heaven and Earth than are dreamed of in your philosophy, Horatio.

The “intersection” between Einstein and Gödel that gives this novel its title was an inflection point in humankind’s history. At some point in the past, enough humans came to comprehend the irreality of the “real world” that, somehow, eventually, they figured out how to transcend it. They set themselves free. Will Lobey’s species — hampered by ill-fitting bodies and hindered by outmoded mythologies — figure out how to liberate themselves too? Will we, Delany’s readers, also aim to liberate ourselves?

Myths can and will control us… unless we study how myths work, and use that knowledge to write our own stories. James Blish, in his complaint about the meta-textual science fiction of the genre’s New Wave era (c. 1964–1983, in my periodization), argues that myth belongs to the fantasy genre, because it explains the world “in terms of eternal forces which are changeless. The attempt is antithetical to the suppositions of science,” i.e., because science believes we can analyze the forces at work in our lives and become masters of our destiny.

Semiotics operates at the “intersection” (if you will) of fantasy and science fiction, then. Like the authors of fantasy, we understand myth to be a real source of “forces” to which we are acculturated to adapt; like the authors of science fiction, we analyze myth and seek ways to subvert and evade its power. We’re neither as passive as the fantasy author, perhaps, nor as arrogant (and naive) as the science fiction author.

Like a semiotician, Lobey’s quest takes him into the dimension of myth — the “underworld,” literally. The most amazing part of the book is the extended sequence in which Lobey hunts down a minotaur (except it’s human from the waist down, not the other way around) in a radioactive underground maze and battles him. Which allows him to learn — from the super-computer PHAEDRA [Psychic Harmony Entanglements and Deranged Response Association], or perhaps it’s an oracle — that his species is “a bunch of psychic manifestations, multi-sexed and incorporeal… trying to put on the limiting mask of humanity.”

“It must be rather difficult,” PHAEDRA suggests to Lobey in a discussion about how his species has inherited humankind’s forms and norms, “walking through their hills, their jungles, battling the mutated shadows of their flora and fauna, hunted by their million year old fantasies. … But I suppose you have to exhaust the old mazes before you can move into the new ones.”

PHAEDRA makes a good point. We do have to make a study of existing myth-systems. But we also need to exorcise them, so that we can go on to live out our freely chosen destinies. We tend to spend all of our time and energy on the former, don’t we? Delany’s book does too.

To reference yet another myth, this tendency is the semiotician’s Achilles heel: We’re addicted to the analysis. It’s a labyrinth at the center of which we hope never to arrive.

JOSH GLENN’S *BEST ADVENTURES* LISTS: BEST 250 ADVENTURES OF THE 20TH CENTURY | 100 BEST OUGHTS ADVENTURES | 100 BEST RADIUM AGE (PROTO-)SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST TEENS ADVENTURES | 100 BEST TWENTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST THIRTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST GOLDEN AGE SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST FORTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST FIFTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST SIXTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST NEW WAVE SCI FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST SEVENTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST EIGHTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST DIAMOND AGE SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST NINETIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST HADRON AGE SCI-FI ADVENTURES.