MAN’S WORLD (25)

By:

December 27, 2024

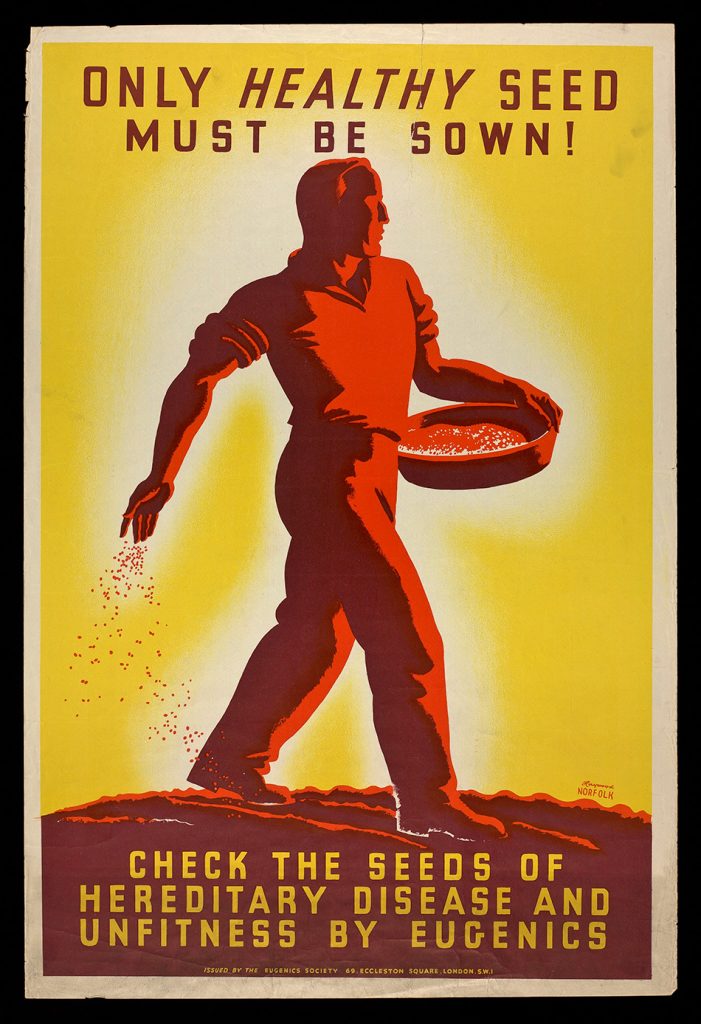

HiLoBooks is pleased to serialize Charlotte Haldane’s 1926 proto-sf novel Man’s World for HILOBROW’s readers. Written by an author married to one of the world’s most prominent eugenics advocates, this ambivalent adventure anticipates both Brave New World and The Handmaid’s Tale. When a young woman rebels against her conditioning, can she break free? Reissued in 2024 (with a new introduction by Philippa Levine) by the MIT Press’s RADIUM AGE series.

ALL INSTALLMENTS: INTRO | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25.

BACK TO THE FUTURE

All science properly so-called, by which I understand systematic knowledge under the guidance of the principle of sufficient reason, can never reach its final goal; for it is not concerned with inmost nature of the world; it cannot get beyond the idea. SCHOPENHAUER — ‘THE WORLD AS WILL AND IDEA.’

Nicolette still slept. Bruce walked across to where she lay, looked for a moment, then paced up and down the room once or twice. He went to the window and on to the balcony. There was no sound but a faint rustling. As he gazed out, the gathering clouds parted for a moment, and through their frayed pearly edges he imagined he saw, outlined against the moonlit blue above them, a moving, dwindling spot. Then they closed again.

Mutely, he wished the boy well on his last voyage of discovery. He had always been so unhappy. Yet he had no more sought to investigate the cause of his misery than he would avail himself of the facile cure. Sad and proud individualist, he had been as self-opinionated as if he had been self-created. Never had he turned to inquire of the woman who had made him — inadequately — nor of those who stood beside and behind her, the ancestry and the blood whence they had both sprung. It was difficult for Bruce, who had long trained himself to view everything sculpturally, architecturally, to enter mentally into Christopher’s flat, pictorial, one-sided point of view. He was penetrated too deeply by his own theories of interdependence and linkage; he was a biologist.

It was fine — the way the boy had gone. Bruce could respond emotionally to an act like that; a clean gesture of cleavage, possible only to one who saw life as Christopher did — canvas through which the knife of will could slash sharply.

Bruce never doubted that he would not come back, but as the slow moments passed his regret became keener. There was a deal to be said for self-ending, from all points of view. And he had enough sympathy to understand the appalling terror with which certain minds viewed the in soluble riddle of existence, the necessity they felt to invent an Ultimate, a resolving harmonious end. He himself was secretly sustained by complete confidence in the continued expansion of the human intellect; he accepted gladly all scraps of evidence which seemed to point to the fact that its power of discovery was kinetic. Quite clearly, if one assumed just a little, thought moved. It soared and fell, like the oceans. What, in the end, might be left of the ground it was ceaselessly attacking — whether the new tracts it uncovered would balance or even outmeasure those that constantly sank and foundered, reveal mighty cities and precious civilizations, or dying, rotting vestiges; whether this new land would itself be gloriously fertile or utterly barren, no man could tell. But at every moment during which one contemplated such problems one seemed to stand at a definite point on a line stretching from infinity to infinity. From the past to the future — from the future to the past — it was enough. Bruce was content.

He went back. He would take Nicolette away, to Nucleus, to the Garden. At once. The sooner it was settled, the easier would the settlement be. As he was about to pick her up, to carry her to the car, he paused. He turned and went to the machine-room. The little one-seater car attached to the hut stood there still, with that curious air of waiting which belongs to machines in repose. The airplane, of course, was gone. Bruce knew what he wanted. He went to the door of a small wall cupboard and opened it. Yes, as he thought, the oxygen was in its place. None had been moved. Intentional or accidental? Bruce knew it was not the latter, since automatically one never went up without the stuff. He shut the cupboard and went back. Brave boy!

He picked Nicolette up in his arms and prepared to carry her out. Sleepily she slid an arm around his neck. He pressed her to him. There was a sound of wheels outside. He stood and waited. Some one was rapidly walking up, trotting now, running. They were short, agitated footsteps. He turned to the doorway. Morgana stood there.

She glanced at them for an instant, bewildered, with dazed eyes. Then an expression of hostility, mingled with alarm, crossed them.

‘Where’s Christopher?’ she asked.

‘Gone,’ Bruce replied quietly.

‘Where?’ she demanded, her hands pressed against her breast.

‘I don’t know.’

‘When?’

‘Five minutes ago. You’ve just missed him.’

Her hands dropped to her sides. She looked at Nicolette and involuntarily lowered her voice.

‘Did you tell him?’ she demanded softly, yet brutally.

‘Yes.’ Bruce’s glance, though quite calm, was too strong for hers, despite its fury. She moved past him, into the room, and sat down with her back to him, wearily.

‘We are just going too,’ he said gently. ‘Back to Nucleus. Will you come with us?’

‘No.’

‘Then, good-bye.’

She did not reply. He supported Nicolette’s weight on one arm. With his disengaged hand he carefully closed the door behind him. Morgana was left alone.

As usual, she was too late. She sat staring stupidly, bestially, in front of her. Her whole consciousness was concentrated, thrown in on itself.

As usual, she was too late. Brian wouldn’t do anything, Christopher couldn’t do anything, she couldn’t. Nicolette — mentally she clenched her fist in the girl’s face and spat. Yes, she should at least have done that. Now it was too late. She had been born too late. She had loved too late, she had never understood until understanding availed nothing. For Christopher would not come back. They had driven him away while she had been rushing to him. She would have made up to him for it all. Together they would yet have done something. She had been cheated, as usual.

Suddenly she saw themselves vividly, pictorially, on that walk to the old Extonian’s laboratory.

‘The only law I recognize…’ she had declared. ‘The only law I recognize….’ What was it she had been trying to say?

‘God’s?’ suggested Christopher softly. They had looked into one another’s eyes.

If only then she had gone to him! Now it was too late.

If he had planned to go away — and for months she had suspected that it would, it must, end like this — why could he not, at least, have waited for her? Together they would have gone so gloriously. But he had gone alone. Alone. She did not speak the word aloud, but she savoured it all the same. Now she would always be alone. Unless? She stood up suddenly, violently. What a fool she had been! It was not too late. Rapidly she felt in her

pockets. No, they were not there. As usual, she had forgotten, until it was… She checked herself. For this, at least, it never was too late. There were a dozen ways of following Christopher, and she need not fear that she would not catch him up — this time. Rapidly she thought. She remembered this place. She had been here before. The lake — she remembered perfectly. Up the path and through the wood, and the hill sloped sharply down on the other side.

As she had come, so she went. She ran. She had to hurry. Although she would not miss him, this time. Up the path, there was a stone, she stumbled; through the wood — a night-jar was sawing the air on a dead branch somewhere — down the hill, first clay, then grass, then moss. She ran, and the wind clawed at her hair as if to pull her back. The bank — ten feet, that was enough. She threw up her hands and jumped.

‘Christopher!’ she shouted.

Bruce had adjusted the hammock bed carefully, placed Nicolette in it, settled down at the wheel, and driven off. The indicator hand on the speedometer travelled round rapidly. Forty… fifty… sixty… seventy… He kept it at ninety. They would reach Nucleus by seven o’clock. It was necessary to get there as soon as possible. Knowing Morgana a little, he imagined she would have come prepared. In the alternative case she would make a fuss, which would be just as awkward. It was necessary to avoid publicity now. And as soon as they reached Nucleus he would see certain people. She would have to be silenced. She was a nuisance. He wished she would have the sense to do the obvious thing. That would be satisfactory, from every one’s point of view. Women like that were useless. Women. Well, there would only be Emmeline and Antonia to deal with in this case. He was not alarmed. That would be relatively simple. He began to think of several jobs he had to do. He would resume his tour as soon as Nicolette was comfortably settled. He was anxious to see Maxwell and find out what Svengaard had been doing. The eminently pleasurable contemplation of his future business reasserted its hold on his mind. He plunged into calculations, details, figures; the fascination of the map-maker, of the man who has will, power, knowledge, gripped him again. He drove on.

‘He’ was kicking hard. She held him in her arms. His eyes, as yet vague, unfocussed, endeavoured to fasten on her face. It was an effort. He made it. It was difficult at first. But he persevered. At last they held her image. He smiled, gurgled at her, kicked lustily with joy and pride.

His kicking woke Nicolette. She found that her arms held him, but her flesh was still between them and his. He had not yet freed himself. He must wait a few months longer. But he was keen to see and to be seen. He went on kicking.

‘He wants to get out,’ she murmured. ‘He’s trying ever so hard. Impatient little creature. Bruce,’ she called, ‘where are we?’

‘Halfway to Nucleus. Are you comfy?’

‘Yes, but I’ve woken up. I want to come and sit beside you. We both do.’

‘All right. Wait a minute. I’ll stop.’

He slowed down and drew in a little to the side of the road. He lifted her over to him and set her beside him. He kissed her on the lips — ‘One for you,’ he said with a smile — and then over the navel, ‘and one for him. Slept well?’

‘Beautifully.’ She took Bruce’s hand and pressed it to her. ‘Feel him?’ she asked.

‘Rather.’ Bruce started again, but did not accelerate beyond fifty. They could go slow for a bit. Nicolette might want to talk.

After a while she said: ‘What has Christopher decided?’

He answered: ‘ I don’t know, but I think I can guess.’

‘I didn’t hear the end of your talk. I wanted to listen, but he,’ she patted her round belly, ‘made me go to sleep. I can’t concentrate for long on anyone but him. Did you help Christopher?’

‘In one sense, possibly. In another, no.’ He turned to watch her expression. ‘I think he’s dead by now.’

Nicolette stayed quite still for a second or two. ‘Oh, Christopher!’ but she remembered him whom she could not for an instant forget. She was a well-trained little mother-pot.

‘Oh!’ Then, ‘How did he die?’

‘I am not certain he did,’ answered Bruce. ‘He refused to consider the suggestions I made to him.’ Nicolette nodded. ‘He flew off and left the oxygen behind. It looks as if he had not intended to return.’

‘What a splendid end!’ said Nicolette gravely.

‘I agree. I admire him.’

‘He won’t suffer any more. He might have suffered more deeply in the future, if he had stayed. Do you think his ideas were queer, Bruce?’

‘Not in the circumstances. Tell me, Nicolette, do you know anything about his birth and the time before? About Antonia’s condition and behaviour, I mean.’

‘No,’ she answered reflectively. I don’t think I do. All I know for certain is that before I was born she had a daughter who owing to some mischance was born abnormal. Antonia never saw her, but she grieved. She wanted a girl, you know.’

‘Much?’

‘Oh, very much. Yet she never made a special fuss about me. Christopher was her favourite. She will grieve for him.’

‘Yes. She should have done that long ago. Do you know if they talked a great deal together, if she ever told Christopher or he ever asked her anything?’

‘I doubt it. Christopher was so tremendously reserved, you know. With every one except me. And Antonia is reserved in a way, too. Although she pretends to herself and every one else that she is completely candid. But why are you asking all these questions?’

‘Because I thought you might like to know what was Christopher’s trouble. You see he tended to be intermediate sexually. I very much doubt whether you father was concerned with that. But I imagine that your mother’s ardent longing for a daughter, although she bore a son, affected him. She must have neglected her exercises — cheated somehow. Physically, at any rate outwardly, he appeared normal enough. But you know what slight modifications you get at either end of the intermediate scale. Christopher’s submasculinity did not cause more than a slight mental perverseness. It could have easily been corrected. But it developed and grew into this sterile mysticism, which led to his self-ending. The excessively mystical impulse always has its root in some slight sexual perversity, both in men and women. You will hear more about it at the Garden. It is tremendously important.’

‘You mean that normal men and women have not got that impulse?’

‘Not as a rule. You can divide the religious into various classes, according to a scale. The extremists who advocate and practise asceticism of the body and contemplation by what they used to term the “soul,” lean towards sterility both of mind and body. The religious desire for and belief in an after-life are the complements of under-developed physical or mental vigour in this. You nearly always find those sort of people terrified of the infinite, incapable of thinking, for instance, in terms of physics or geology or mathematics. You heard how appalled Christopher was by my attempt to make him think rationally about the stars.’

‘How do you explain the so-called religion of the people in the old days, then?’

‘The white race has never been fundamentally mystical. It is far too virile for that. But the alleged belief in an ulterior world was an excuse to overthrow and to establish institutions or customs in this, to go to war, or to reformations.’

‘”Think not that I am come to send peace on earth,”‘ answered Nicolette; ‘”I came not to send peace, but a sword.”‘

‘Precisely. What could be more clearly a declaration of policy than that? It served the activities of our race well. And it only endured so long as the Christian Church, like its predecessor, the Roman Empire, had a policy of action, and was run by vigorous men of action — Paul, Ignatius Loyola, Luther. When it ceased to govern and to act, to be political, Christendom in the West was doomed. Science provides our basis of policy, but the same type of human intelligence, the active type, still leads and governs.’

‘You see how essential for us it is,’ he went on after a pause, ‘that the men and women of the governing class shall be as normal as possible. If they were not, our power would wilt away in a few centuries. We have no use for sterility, for above all things we aim to keep the race going until each individual shall have achieved complete self-consciousness. A self-conscious race: it seems to me worth while, that.’

‘And to me,’ answered Nicolette. But it won’t be for a long time yet.’

‘Not for a long time. That is our privilege, to go on building towards the completion of an edifice we shall never see crowned. And it is a test of our value that we should be able to face that realization and yet not flinch. That we should continue the experiment begun by this race thousands of years ago. In the meantime there will always be Christophers, and they will always suffer. But it’s the experiment that counts for us, not the result.’

As he spoke, Nicolette was compelled by his fervour to turn and look at him. His steady hands gripped the wheel. He looked with dark, clear-visioned eyes through narrow lids straight ahead at the shining road before them, that led up and down, over hills and through valleys, to Nucleus, back to the future.

And as she looked at Bruce, Nicolette began weeping gently (so that ‘He’ might not be disturbed) for Christopher.

THE END

RADIUM AGE PROTO-SF: “Radium Age” is Josh Glenn’s name for the nascent sf genre’s c. 1900–1935 era, a period which saw the discovery of radioactivity, i.e., the revelation that matter itself is constantly in movement — a fitting metaphor for the first decades of the 20th century, during which old scientific, religious, political, and social certainties were shattered. More info here.

SERIALIZED BY HILOBOOKS: James Parker’s Cocky the Fox | Annalee Newitz’s “The Great Oxygen Race” | Matthew Battles’s “Imago” | & many more original and reissued novels and stories.