MAN’S WORLD (24)

By:

December 19, 2024

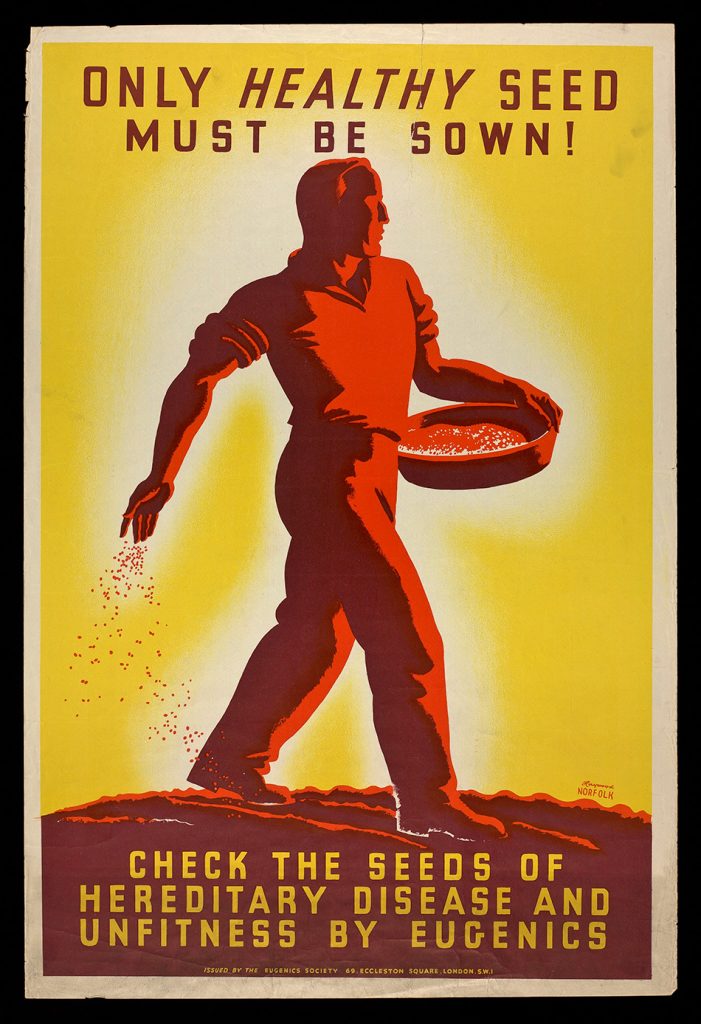

HiLoBooks is pleased to serialize Charlotte Haldane’s 1926 proto-sf novel Man’s World for HILOBROW’s readers. Written by an author married to one of the world’s most prominent eugenics advocates, this ambivalent adventure anticipates both Brave New World and The Handmaid’s Tale. When a young woman rebels against her conditioning, can she break free? Reissued in 2024 (with a new introduction by Philippa Levine) by the MIT Press’s RADIUM AGE series.

ALL INSTALLMENTS: INTRO | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25.

UNREALITY (cont.)

Christopher more or less stumbled into the room whence Nicolette had called, obeying her call subconsciously. There were sounds still ringing in his ears which left no room there for the perception of alien tones, or he might have been aware of a strange quality in hers. The room was brilliantly lit, and entering from the darkness, he saw her face, in the first seconds, only as a familar blur…. And minutes passed, minutes of greetings, smiles, before his eyes focussed on her properly. His eyes informed his ears; he became aware, now, of a profound change in her appearance, yet his imagination was still so far away that he asked, stupidly: ‘Nicolette? Is it really you?’

And Nicolette was about to answer automatically ‘Yes,’ before her own new knowledge slipped in a pause between the opening and closing of her lips. Was not that just the question she had come to answer? But not so.

Christopher had already met her eyes. He frowned and peered a little, still blinking. Then, passing his hand rapidly over his hair, said: ‘Don’t speak. I can see.’

‘Can you, Christopher? Already?’

‘Yes. And what I can see in your face — what you have come to tell me, dates from before your pregnancy, doesn’t it? So you could still have chosen; it is obvious how you chose; all you want to tell me is why, isn’t it?’

‘If I can. It is difficult.’

‘Perhaps for you. Not for me. At least not yet. It’s so easy to see. Something of you, and so of mine, has passed out of your own into Bruce’s keeping. Bruce isn’t one of us, as I might have suspected. He’s too old. Did you realize that he is too old, or were you beyond knowing even that? Are you no more young, Nicolette?’

It became easier for both of them when he had pronounced those rather fantastic words. It confirmed the nightmarish quality of this scene. It was easier at once to act stiffly, clumsily, as they were doing, the moment the unreality of this encounter was driven home. And as always during such periods of emotional tension, when time conceptions become absurdly distorted, thought comets flashed across the empty darkness that just now appeared to them to ‘stand for’ their ordinarily clear, well-stocked minds. Some part of Nicolette’s consciousness was now following such a zigzag trail, that flashed out: ‘Lucky we understand one another so well; we can suffer together, equally.’ Whereas Christopher was aware of a ghostly, ghastly laughter, flitting about there ceaselessly.

He was trembling, and his voice was low as he went on. ‘Oh yes, I think I understand the present position perfectly. But the past? That, in the light of it, seems so absurd. That you had better explain a little.’ Then there was another flash in the background of his consciousness, but this he took hold of and brought out in words, as a flash of inspiration.

‘I say, Nicolette, let’s fly! Shall we?’

‘I… I can’t,’ she answered piteously. ‘It makes me sick.’

Then Christopher felt the sting of tears in his eyes, and heard himself laughing, and he continued to laugh, but he pressed her gently into a chair. He knelt beside her, took one of her hands in his, kissed and fondled it a little. Nicolette stroked his hair with the other. They were silent for a moment or two, both suffering about equally. Christopher after this small pause spoke gently: ‘Never mind. I am just beginning to think… I don’t quite know yet… but probably I have behaved absurdly all the time. I was your shadow baby, wasn’t I? And now those games you played to make me happy are finished, because you’re going to have a real one. Yes?’

Nicolette nodded. ‘But couldn’t you grow up too? Please, my dear?’

It was all getting more unreal and more easy from minute to minute.

‘We’ll see. But on the whole I doubt it. What should I grow up for? Anyway, it was nice of you to come to ask me.’

‘Isn’t there anything, Christopher, anything at all?’

‘I shall be angry if you try to take my dreams away from me, little mother-pot. I am going to keep those till the end — right to the end. You have come to show me that they were and are only dreams, but you can’t banish them. You have lived with them long enough to know that they are Christopher. What you call my dreams, and I my realities. You were part of them once, or rather, there was a Nicolette in them. But now — you — here——’ He had begun to walk up and down, and he flung out his hand to her ‘Oh, you could never persuade me that you are real, that this Nicolette-Bruce entity of which half is before me now, that it and its background, with people and rules and all the rest of it, are real. Try if you like, tell me something. Talk to me.’

‘Bruce could talk to you more convincingly than I, if you would care to see him. He’s waiting for me with the car. Would you?’

‘Yes. I want to see you together. I haven’t ever yet, really, you know. I couldn’t.’

‘Didn’t want to wake up, you mean, don’t you?’

‘That’s putting it your way. I might say, “Or go to sleep — forever.” Opposites mean much the same thing, anyway. Call Bruce.’

As usual when Bruce entered, he filled the room with comfort for Nicolette. The dark mental background immediately lightened. Seeing these two together, now, whom she loved, she felt her self loving Christopher more for Bruce’s presence. Almost she fell a-brooding on this masterpiece of sensation — Love. But they began to talk, and she to listen.

‘Why didn’t you come up?’ asked Christopher. ‘I didn’t know you were waiting out there all this time.’

‘Nicolette preferred it; it doesn’t matter. I’ve been watching Mensch and Descartes. But I could not see much out there. You haven’t a spy-hole here, have you?’

‘No. There ought to be one, but it’s rather an old hut. Have they decided about Jesus yet?’

‘In principle, but not in practice. The difficulty seems to be to find an appropriate constellation. But you know how long the popular mind takes to make itself up.’

They all three of them went to the balcony and stood there a moment, looking out and up. Christopher laughed quietly.

‘We’re pulling down the stars for them to play with, now,’ he said. ‘What next, I wonder?’

‘That’s not quite fair to us, surely,’ answered Bruce gravely. ‘Do you realize that since astrology went out, great multitudes of people never glanced this way once throughout their lives? Comparatively few years ago, Mensch had a struggle to get elementary astronomy into the school curricula. Yet without it, no human being can begin to have an adequate sense of proportion. This game we’ve started them on now is just a beginning. In another twenty years we shall be getting them somewhere up to the mark.’

Christopher turned his back on the balcony and re-entered the room.

‘Your enthusiasm spoils the stars for me, like everything else, Bruce,’ he said calmly.

‘I’m sorry, but why should poets and astrophysicists have a monopoly of them? People like you and me…’

‘Oh, people are you and me; or were once, before your accursed medicine men got hold of the world and started tinkering about with them. Where’s it going to end? Isn’t any one going to pull them up? I marvel, when I look back to the beginning of the scientific era, that no one, not one single man, foresaw what it would all lead to —’

‘Butler,’ interjected Bruce.

‘Oh, possibly, yes. But not in its monstrous fullness. Not in its personal implications. Not in its power over the mind and body of each one of us. I mustn’t even mention the word “soul”; if I might it would not convey anything to you. Tell me what there is in this world of yours for a person like me! You, with your hundred per cent. man and your hundred per cent. woman, with your normality and your dreary talk of intelligence. I’m glad I’m not one of you! As long as I live, I shall feel an undying loathing of it all. You draw a map of a man’s consciousness as you do of the “genes” of a rabbit. You tinker about and fiddle about with every living thing; you babble about “lethal factors” and “survival value,” and all your other nonsense. Do you mean to tell me seriously that you attach the slightest ultimate significance to it all? Even as I speak to you, I can see what you are thinking. Neurosis, due to whatever you like to call it — and if we gave him so and so, and mucked about so, and with a few hefty doses of hypnosis, we could make quite a nice, normal little man of him.’

‘You know why I’m talking to you like this. I know Nicolette’s put you up to try to “reform ” me. Something ought to be done about me soon before I make any mischief. All these years I thought she loved me — she may still think so — to-night I know she was only mothering me, trying to protect me. One finds people out so suddenly! The moment I saw you two together I knew. I fled. You come after me. I don’t mind seeing you both to-night. But we’ll have it out finally. You must leave me alone. There’s nothing, absolutely nothing, you can do for me.’

‘I’m sorry you’re so antagonistic to me, Christopher. After all, I have fallen in with your scheme as far as it was practicable. When Nicolette has had her baby you will have to recognize that. But it would be folly to go to the lengths you suggested. You would defeat your own object.’

‘How do you know?’ Christopher asked hotly. ‘Did any of the people of old who felt as I did reckon like you do? Were they prudent? Were they careful? Have none of you ever known moments of complete consciousness, of mystical union with God — yes, with God and His Saints, when a Voice has called to you “Go thou and do likewise!” There isn’t any object but that, to go straight on to the bitter end, the end that is just a beginning…’

‘I can’t argue with you about mysticism, Christopher. But if you talk about consciousness, there is something to be said. There doesn’t seem to be much doubt that to all of us, occasionally, come those longer or shorter periods of a realization that seems complete. In the old days this process of intensive thought was symbolized as an act of going up to a great height and holding communion with a god. When Moses went away to think, he came back with a law he had worked out, prepared to give it to his people as a divine revelation. Now whenever one “comes back” in this way the rest of the world does appear to be worshipping a golden calf. But we’re trying to do away with the symbolism of mountains in connection with thought, and we manage to govern without revelations, and we study stupidity instead of punishing it. Moses was a father of science, not merely of a church, and we use precisely the same methods to-day as he did, only without the trimmings. They’re superfluous already. That seems to me an encouraging sign. The more familiar we become with the processes of thought, the more easily we shall be able to maintain a high level of thinking over an increasing period. But for the next few thousand years the thinking of the human race will have to be done for it by a few men at a time. And they will make occasional mistakes, which I expect will decrease in number and importance. That those men must be “inhuman,” as you mean it, is inevitable. To be human in your sense is simply to be emotional. Feeling is not thinking and one has the utmost difficulty in convincing most people of that simple fact. To admit it is to admit something requiring the utmost courage and fortitude to endure, and those who have not enough must invent a god to salve their feelings.’

‘Stop, Bruce!’ Christopher’s cry was imperative. ‘It’s no use going on. I’m not listening to you. I’ve hardly been hearing you. My ears are full of other sounds. Bruce——’ He pointed to Nicolette. Her eyes were closed. There were tears on her lashes. She was asleep.

‘Bruce,’ said Christopher softly, ‘long ago, when we were quite small children, I used to see her asleep like that. And I have never loved her so much as in those moments. But as a lover you can do more for her than I. I am glad you have taken her, happy about that, Bruce. Now stay here with her. I am going out for a while. I prefer I to be alone.’

‘Won’t you —’ Bruce did not complete the sentence, but he laid his hand on the boy’s arm. He knew he could do no more, but he was filled with pity. There was, of course, just one thing….

Christopher stepped back. His eyes met Bruce’s fully; his glance was keen with honest hatred, unyielding and clear.

‘No, I will not.’

‘Then — be careful.’

‘I will. They’ll have to come a long way for me.’

He went quite softly, but he did not look back.

Christopher did not attempt to think at all until he had climbed a few hundred feet westward. Already the little shack in the velvet woods lay a long way below him. But now time and space, which had so often provided the theme for delightful speculations on previous flights, were nothing to him. He had passed through the belt of light mist which had been gathering earthwards when they had come in from the balcony, and the stars, more than ever like spots on a one-coloured map, lay before him. But they did not tempt him to-night to draw imaginary roads from the Sickle to Orion, through Castor and Pollux to Aldebaran, roads of discovery through infinity.

They did, however, recall him after a time to self-consciousness. They reminded him of Bruce, who had spoiled the stars for him. Still he did not notice how his hands trembled, although through familiarity his grip on the stick was firm.

‘Everything seems about finished.’ No, those words had no meaning. He might repeat them with his lips, he might bring them forward to stand out brightly against the sombre background of his mind, as those stars stood out against the sky it was futile, they had no meaning. ‘Everything…’ who can define that? ‘Seems’… that’s a little better is,’ or ‘may be,’ — he rejected ‘may be’ violently and repeated ‘is’ with determination. ‘Finished’ — what nonsense! I mean, of course, ‘Begun.’

That was clearer — much clearer. Christopher had not the least doubt that this was definitely a beginning — perhaps of something important. Beginnings — of days, of litanies, of the unfolding of flowers, of symphonies — beginnings were invariably beautiful. He couldn’t think of an ugly beginning, and as he searched a score of quotations tittered through his mind. ‘Our Father, which art in Heaven, hallowed be Thy name,’ — what a beginning! He repeated the invocation several times, and mercifully had no need to reject the memory of the following request: ‘Die Sonne tönt nach alter Weise?; came next, ‘In Brudersphären Wettgesang, und ire vorge schriebene Reise vollendet sie mit Donnersang.’ And then, ‘In the grey beginning of years, in the twilight of things that began. The word of the earth in the ears of the world, was it God, was it man?’

Christopher was weeping, and when he noticed it, was a little surprised. Surely all that was far beyond tears — what had brought them down? That last unimportant word lingering in his mind, of course. Although he was sorry to find he still cared sufficiently to weep, Christopher could not shake off its influence. Words were having a curious effect on him just now, apparently. Apparently, then, one had to say good-bye. These small ceremonies seemed inevitable. He turned his head half to one side and downwards, but the clouds were all below him, and he was relieved to find that he could not, even if he wanted to, see through them.

Still, he was sorry. He let his tears run, let himself be filled with the sorrow that prompted them, the enormous, heavy sorrow that, if indulged in too long, leads to sleep. He was sorrowing for those little creatures, that curious race down there, sorrowing as the gods, as the Great God Himself might sorrow, a long way further up, every now and then. Even here, far away and free as he was, he took with him the ancient sense of kinship. He suddenly realized that it was this, precisely, he had come up here to lose.

Nothing new about this desire. He felt an invading sense of kinship with his forerunners, those who had also sorrowed for man and withdrawn from his contacts, and he felt a regret that they were not all with him here, that the Makara was not a vast mythological ship on which all those who had been compelled to fly from earth could have embarked with him. What comfort had common man not devised for his superiors when he had built them aeroplanes! He had abolished the necessity of dwelling precariously on hilltops or in caverns in order to await the purging of the soul and the complete filling by the divine spirit. Where they had perforce crouched, he could spring, soaring to meet revelation half-way. It was movement they had most lacked, he thought, not having known how to unleash the potential energy that should enable them to soar physically also.

Already the edges of his sorrow were fading into indifference. The higher he climbed, the more easily could he forbear to look downward and backward. The whole earth now seemed unreal to him; as clearly unreal as the last hour he had spent on it, when the message of his symphony had been succeeded by the pleading of Nicolette and the warning of Bruce. He had heard neither, for his head was filled with other voices, but he had seen them, looked upon them both as one looks with lazy curiosity at strange shapes on waking up in a half-light, after having fallen asleep in the sunshine.

Nicolette… had he really seen her for the first time to-night, or had some new individual slipped into the personal form of the small sister he had loved so many years? Whose were those sad, doubting eyes that had looked from him to Bruce? Eyes — oh, yes, he had seen clearly enough — that lightened and cleared as their glance travelled Bruceward. He was not a bit sorry to have left that Nicolette behind; it was quite certainly not the same creature, and, dwelling on the other, he exclaimed with a sudden sense of revelation: ‘I invented that girl!’

Ah, yes! he had invented her, because, until now, he had felt so heavily the need of a companion on that pilgrimage he must make alone. And yet he seemed to remember having told her, long ago, when he could formulate his thoughts more easily by speaking them at her — he seemed to remember having warned her that he must go alone. He had had need of company, nevertheless, and until this real Nicolette had unfolded herself, the dear little invention had been loyal. For naturally his invention had been a sexless companion, the personification of no other emotion but loyalty. When the generative passion had turned that child-friend into womanhood the invention had crept away, slowly and timidly at first, and then at the last vanishing swiftly in a glitter of tears.

That word sex (words were like stepping stones in the pools of thought to-night) — that had to be thrown overboard too, before Christopher could soar freely towards his destination. It was another feeble monosyllable, a euphemism, masking emotions which had been institutionalized by man. You might turn away from it, with draw, deny, deny, deny — it was useless, down there. Neutrality was not negation. On that ground you were either one of the army of propagatives, or an enemy whom they would ultimately extirpate. Moses and Luther between them had seen to that. Their modern successors did not preach; practice was more efficient. It was not the homosexual body they dreaded, but the homosexual soul; the soul in which the seeds of ‘love’ were doomed to infertility, the soul that was sufficient unto itself. From that high self-satisfaction one was tempted indeed, tempted to stoop down and preach to those other poor souls, seeking in their desperate want the unattainable mate; if only to help or to comfort, one offered a part of one’s own secret wisdom. And at last, exasperated by their stupidity, their coarse unintelligence, one wanted to teach, not gently nor with words, but by deed or gesture, meeting violence with defiance.

Till at last, wearied of them and all they did or were, one recoiled once more into the worthier preoccupation with the quintessential problem.

Not a last thought for Emmeline, for Antonia, for St. John? No. Christopher had flown a long way by now. The Makara was groping her way more cautiously, travelling further and further forward, in order to get a little and a little higher. Christopher put her into climbing gear, and turned on the raiser. She would be all right now for a bit — let her have her head.

It was later that he felt the dropping of the temperature and switched on the radiator. The molecules — no, one could quite easily think of atoms now — were separating, moving about more happily, for there was more room up here. One could expand, could stretch mentally and physically, for there was room — so much room!

Later. The Makara was sailing along steadily enough still, on her own sweet road — Christopher’s only in so far as it led further and further forward and a little higher and higher. He had ceased to think vocally for the past fifteen minutes; marvellous thoughts came in increasing numbers, but it was unnecessary up here, where there was so much room, to group them in sequence. There did seem, though, at the back of his mind, dimly apprehended, a thought that wanted to come forward, yet could not get through. It translated itself into an unpleasant sensation in order to find an easier path, a sensation as of something forgotten that made one want to click the fingers and press the tongue against the teeth — tk, tk, like that. Christopher could hear the click of his fingers, but was un aware that as he repeated the motion his thumb and index finger were fully two inches apart. Tk, tk — what was this that had been forgotten and that could not get through?

Here was God — indubitably: it was like going to the top of the mountain. He had known all along that when once those grimacing voices had been left behind he would hear THE VOICE, just so, like this, its music getting ever louder and clearer as one climbed forward and upward. His own music came back to him, but it could not compare with this, though it was the same — but this…. The thoughts fell away abruptly, nothing now remained but the mighty music. Tk… tk… Oxy.… tk… tk… Oxyg…

There was something intruding on the music. Something very small but significant, annoying, something that must be eliminated. Tk… tk… He could hear it now in spite of that glorious thundering. It was a mere word. Just listen for a second more and then it will fade away. Tk… tk… Oxygen.

Oh, was that all? ‘Oxygen,’ Christopher shouted, but the shout emerged from his throat a whisper. There was so much room up here. And suddenly he understood with extraordinary clearness, not that he had forgotten the oxygen and was going to die, for surely that was exactly what he had intended and there was no need for the intrusion of that ignoble clicking, none at all; he understood that he was about to enter into the kingdom and the power and the glory, and they into him — that, borne upward on the wings of those unceasing harmonies rapidly becoming visible, taking shape as their anticipated forms, he was going to…

For he had now cast off all superfluities, he was now transcendental, soaring quite free and yet fused with all eternity….

He was now lying crumpled up over the stick. Purple blood was trickling from the nostril he had declined to cover with the protective mask — purple swiftly crimsoning on the glass edge of the clock face he had smashed in his fall.

The Makara continued faithfully to bear her little upward, passenger further and further, but ever so slowly a towards the forbidden heights whence soon she would wrench him, swooping through space, downward and backward, downward and backward — where he belonged.

RADIUM AGE PROTO-SF: “Radium Age” is Josh Glenn’s name for the nascent sf genre’s c. 1900–1935 era, a period which saw the discovery of radioactivity, i.e., the revelation that matter itself is constantly in movement — a fitting metaphor for the first decades of the 20th century, during which old scientific, religious, political, and social certainties were shattered. More info here.

SERIALIZED BY HILOBOOKS: James Parker’s Cocky the Fox | Annalee Newitz’s “The Great Oxygen Race” | Matthew Battles’s “Imago” | & many more original and reissued novels and stories.