MAN’S WORLD (22)

By:

December 5, 2024

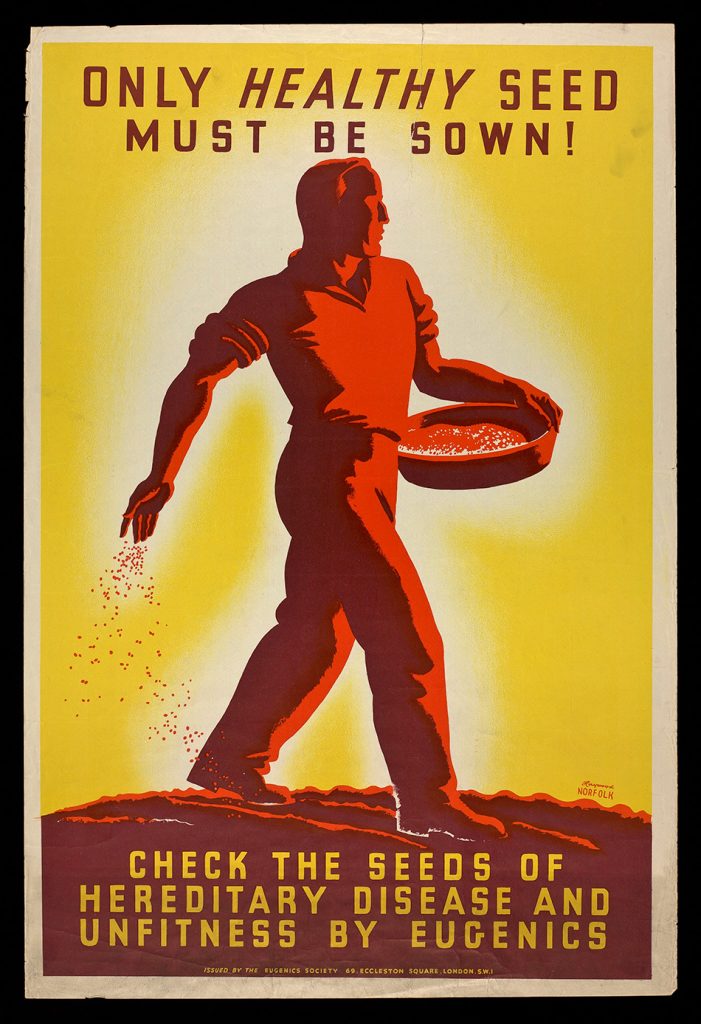

HiLoBooks is pleased to serialize Charlotte Haldane’s 1926 proto-sf novel Man’s World for HILOBROW’s readers. Written by an author married to one of the world’s most prominent eugenics advocates, this ambivalent adventure anticipates both Brave New World and The Handmaid’s Tale. When a young woman rebels against her conditioning, can she break free? Reissued in 2024 (with a new introduction by Philippa Levine) by the MIT Press’s RADIUM AGE series.

ALL INSTALLMENTS: INTRO | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25.

USNESS (cont.)

It was difficult for Nicolette to refrain from ‘showing off’ Bruce to her friends. It was not so much the fact that he was already well known, and likely to be famous in due course, that prompted her. Partly her pride was the usual pride of the healthy young female in her mate, but chiefly it was actuated by a deep and powerful respect for the superiority of his mind. For he was not the sort of person one ever had to make allowances for, or who needed sympathy, tolerance, understanding. His intelligence was a perfected instrument, as integral a part of him as his physical vitality; he was almost incapable of imagining the difficulties that faced those less well endowed than himself.

Since Nicolette had moved to the artists’ dwellings, she had a large room for her own needs. On the evening of the second day of Bruce’s visit, Christopher, Brian, and Morgana came there to meet him, and one or two others came for a short time as well. The conversation, as Nicolette told him later, reminded her of a chess tournament, at which a champion takes on all the other players simultaneously. ‘Now let me see,’ she teased him, ‘if I can remember the subjects you tackled them on. You began with Christopher on music. Then Ewen, your young physicist friend, got on to sound. We all joined in a bit, to his annoyance, and there were some jokes about Farnell’s talking machines. After that we had more on communication, and before we could stop you, you were on to the use of crystalline liquids in television. Then — I don’t remember how, you started something about the racial boundaries controversy — oh yes, that was Morley’s fault, that red-haired patrolman; and after that you told us those thrilling stories of the experiments on the adrenal cortex of negroes. And there was a lot more I can’t remember, because Morgana got bored and prevented me from listening.’

‘I must apologize, darling,’ said Bruce contritely; ‘I didn’t mean to bore you, but I wanted to find out what they are doing here. After all, it’s what I was sent for!’

‘I wasn’t bored a bit, only Morgana got impatient. She won’t like you. I think she had expected more personal talk.’

‘But it isn’t interesting. After all, who cares what we think, or are? It’s what people are doing that is worth hearing.’

‘Of course it is. We do talk about ourselves to a ridiculous extent.’

‘Quite natural at your age. Anyway, I want to talk about you now. Come and sit down.’

He lifted her on to his knees and ran his hand through her thick curls with a sigh of satisfaction.

‘What are we going to do about ourselves, you and I?’ he asked, and pressed her closer to him.

‘In what way?’

‘Well, I want to know just what I mean to you. Once before I was a fool, and didn’t talk things over with you. If it is not too late, I want to now. You see, I shall always be a bit of a bore, like I was to-night. Doing things and getting to know what other people are doing is all I care about. How do we stand towards one another?’

‘Tell me first what you feel about me,’ she answered softly.

‘Oh, I adore you. When I first met you I thought, as far as I ever do, that when you grew up I would offer myself to you “for keeps.” There is not much to be got out of sexual experience unless there is that feeling of permanency about it. It’s not easy to explain, but as a man grows older he does want the knowledge of an established and lasting affection, colouring everything for him. To most men that kind of desire does not come until they are about forty, but with me it is different. I’m an instinctive monogamist. That was why I did not hurry with you. I thought I would wait until you were old enough to mate, and see if I could give you that same feeling about myself. Then we could begin having children. But when I arrive I find you have been doing all sorts of things on your own. Tell me what you really have been doing, and why.’

‘What is easier than why. When I went away I was worried about Christopher. I came back and found he had a lover, and that apparently he did not seem to need me at all. I had felt that you understood about him and me — and then, there was no one. They wanted me to mate with Raymond — I just couldn’t. Suddenly Christopher came back to me. I was restless… oh, I can see now that I wanted you, I was ready for you… but I had looked on you as so much older and wiser than me. When I was with you I stopped thinking or trying to think — we always talked about things, not people. Well, then, I wanted something to do. It is such fun doing things — so I joined Weil for a time. And as time went on, I got less and less interested in motherhood, and somehow I did not want to be immunized. But I had to decide. Christopher did not want me to become a mother either. You know how critical he is of everything, how he believes in anarchism and free-will. He has always been like that, ever since he was a child. He has no community sense at all. One day we were talking about things in general with Morgana and her young man ——’

‘Is that Brian?’

‘Yes. We had been discussing Exton, and we all felt revolted. We agreed that we would try to do something for individual liberty, but we did not know what. Then it turned out that, supposing I wanted to retain my chance of motherhood, it might be possible to forestall immunization. They asked me if I would risk it. It was just the kind of thing Christopher was keen on, of course. You know he has always had a grudge against the rules….’

‘Something to do with his dislike of Adrian, I gather.’

‘How did you know?’

‘Well, it’s fairly obvious. Adrian is rather trying.’

‘Yes, but I think there’s more to it than that. Christopher is revolted that men should be able to impose their will so completely on their fellows. He feels there ought to be another power, something more spiritual, to which one can appeal. He is mystical… religious… he wants to believe and yearns for something beautiful, something that isn’t ephemeral and futile like all this. He wants it to be manifest in some way — provable. People won’t listen to that sort of thing. But he — we — thought, that if we did something to startle them, something unusual, they would be roused. They would have to inquire our motive. And we could justify our belief by risking the consequences, and giving them a lesson.’

‘H’m. A doubtful sort of logic, it seems to me.’

‘But Christopher isn’t logical — that’s just the point!’ Nicolette sat up and looked at him imploringly. Her eyes were eager and bright, her cheeks flushed. ‘Don’t say what any one else would,’ she begged him. ‘I love him!’

‘Of course you do,’ he soothed her, ‘you dear child.’ He pulled her to him, gently, and beneath her head she could feel his wide soft breast under the thin shirt, and the steady beat of his heart. That was a new sensation, new and exquisitely beautiful. As she lay there, all the nervous tension seemed to go out of her, oozing, ebbing away at her finger-tips and toes. She did not recognize it, did not know love could be like this, a bathing in alien strength that soothed like a cool wind and warmed like a gentle sun. Something new happened to her at that moment: it was as if a part of herself, the puzzled, fretful, immature part that had always been imprisoned deep in her consciousness, arose and left her, flying from this magic communion, leaving behind a strengthened being.

They were silent for a moment, lying thus so closely, so harmoniously, that it seemed as if they were being inseparably fused together.

Then Bruce said: ‘Tell me the rest.’

‘I decided,’ she continued after a second’s pause, ‘that I would let myself be immunized, but that I would do something first to prevent it having effect. Brian thought it possible, and promised to get me some stuff. He was interested in the experiment for its own sake. He went abroad for it.’

‘Who gave it to you?’

‘I did, myself, with a hypodermic. It was quite easy.’

‘And what do you intend to do now?’

‘Well — what do you suggest?’ She sat up, shook back her curls, and looked at him expectantly. ‘I won’t let Christopher down!’ she declared.

Bruce gazed back at her solemnly for a moment.

‘And what about the child?’ he asked.

‘If you’re willing I’ll have it, and risk the consequences.’

‘I think your pluck is magnificent, my dear,’ he answered, ‘but what about the child? Have you considered it from his or her point of view?’

‘That does not matter, surely. The child has nothing to do with the point at issue. It’s only got to be born.’

‘Oh! And supposing it is not allowed to live? I am not so sure that it will even be allowed to be born.’

‘I could go away and hide, and only let them know afterwards.’

‘And if you did — what then? They could still eliminate it.’

‘But that would be outrageous!’

‘Not a bit, according to the rules. No more than your conduct would appear to most people. You would have lied, cheated, committed the gravest possible infringement of the biological law; it’s a serious thing, you know, what you’re contemplating.’

‘We mean it to be!’

‘All right, then. If you are prepared for the consequences you must decide. But mothers have a way of becoming fond of their offspring and of wanting their children to live. Especially the first child.’

‘Then you will not agree?’

‘On my own terms, perhaps, but not on Christopher’s. As an experiment, although it’s unusual and a bit risky, it can be done. I can justify it, though of course they will object vigorously at first to our not having asked permission. And to that picture Arcous has done of you. But that could probably be arranged. The rest is out of the question.’

‘Then you want me to betray Christopher? To take away his last chance of vindicating himself? It would be the end of him!’

‘I want you to convince him the scheme is impossible. It’s fantastic. And I think it quite unjustifiable to expose you to the risk.’

‘But we should all be in it, not merely me. It’s a collective scheme. After all, the rule is detestable. It should be abolished. If we take a stand, and let it be known, we can make it into a strong agitation for personal liberty. We should gain sympathy. The movement would grow.’

‘Little darling, you would not gain an atom. To begin with, nothing would ever be known. Even now, the Patrol may have an inkling of what you are planning, and be just waiting for you. I know about these things. Do you think that people who, in the common interest, can eliminate whole cities and keep enormous tracts of land clear of a single human being, who command the intelligence and the weapons they command, would consider five silly little people like Christopher and you and me and Brian and Morgana? Does any one else know?’

‘Arcous.’

‘Your artist friend?’

‘Yes. He’s one of us.’

‘How can you be certain? He’s a Jew, and they’re much too sensible to take life seriously. He probably thinks it’s a great joke, and that’s the only thing they can never keep to themselves. No, dear. It won’t do. But we won’t discuss it any more now. Think over what I have told you. I shall be in Nucleus for another six weeks. After that we might even travel a little together, as you are technically free to live with me if you want to. You must get to know me, to find out if you really do love me. Then we shall see. I am not sure, you know,’ he said with a smile, as he lifted her on to her feet, ‘if you really have room for me in your mind, or whether you’re in love with that charming brother of yours.’

‘He is charming, Bruce, isn’t he? ‘Like the child she still was, she wound her arms around his neck pleadingly. ‘And you must learn to love him, too.’

‘I will, my dear,’ he answered as he kissed her good-night, ‘if we can help him to think like a man.’

Nicolette decided that the time had come to take an inventory, to find out to whom, for example, Bruce had delivered his ultimatum. For it was clear that in this crisis the matter of supreme importance was to discover, more or less exactly, what it was ‘she’ wanted.

Nicolette was not intellectual, nor even clever. But she possessed, like her father, that fundamental honesty of mind and character that must recognize fearlessly the impermanence and instability of the human ‘self.’ It was precisely on account of this vague, hitherto not even defined doubt of her ‘real’ self that she had been so adaptable, so excellent a convert. She had never been sure of anything whatever, least of all her own thoughts, so that it had been easiest hitherto to follow a lead and to pretend to herself and others that she took certain things seriously — more seriously, at any rate, than most people.

So-called absolute standards of thought and conduct were, of course, generally condemned in her day, save by such violent reactionaries as Christopher. He was one of those people who only managed to find some escape from the conflict of their emotions by sub-editing them. Two or three generations ago most men lived, or at any rate had managed to get through existence, by such methods. Clichés, headlines, symbols of all sorts were like the rungs of a fire-escape ladder, on which they had managed to climb out of reach of the torments of thought.

Nicolette determined that she would try to think things out. And then there jumped into the range of her mental vision a picture of a carpet of blue scillas, a vivid tag of memory, connected in some obscure way with other tags that represented a flight with Christopher and one of their many talks together a few years ago. This flower-picture appeared to be mingled with a feeling of acute satisfaction, and it started a train of others. They seemed, all of them, to be little things like children or bits of scenery or flowers (many of them flowers) or small masterpieces in porcelain or sculpture…. They were many, yet all small, and all harbingers of the purest pleasure she could know, apparently, a pleasure to be obtained in no other way and that, certainly, had never come to her through any grown-up person whatever.

Then, the other night, she had laid her head on Bruce’s breast, and there, for the first time in contact with a human being, she had known that emotion in its perfect form. What did it mean?

When she had attempted to describe to Bruce this sensation he had given her, he had appeared to understand exactly what it meant and had said that he had felt it himself, with her, and only when with her. ‘The absence,’ he had said, ‘of all sense of tension, and a feeling that the bonds of our personalities had loosened, so that in some way a fusion, a melting into one another, seemed to be taking place between us.’ If you said ‘Us,’ — called it Usness,’ — the thing, the formless emotion or sensation or whatever it might be, seemed to respond to that name, to take on form.

And that alone, of all sensations possible, seemed to correspond and be in harmony with her feelings about those absurd small things, feelings difficult to describe, even to translate into thought, because they were dependent on such tiny stimuli, but which, nevertheless, now she attempted to discover herself, did seem to provide the nucleus of the real Nicolette. Trying to imagine the absence from her world of perception of all the things that could arouse this emotion in her, she concluded that it would be an intolerable world, one in which she would suffer, be — it was difficult again to find a word for something so alien to her imagination — yes, be unhappy….

Because of this and no more, she knew herself indissolubly bound to Bruce. There was Christopher, whom she had loved consciously all her life, with whom she had formed an intimacy which neither of them had thought possible to establish in relationship with any one else — yet all this passionate affection, which had declared itself in speech and deed and finally in an almost despairing appeal to Bruce to understand it, counted for nothing as against the sensation of ‘Usness.’

It was mysterious, appalling; it was an insoluble riddle, apparently — but there it was. She would soon begin to know the meaning of the word ‘unhappy,’ she would be disloyal, she would betray Christopher’s utter trust in her, she would refuse at the crucial moment to back him up — but however this might affect her self-respect, however keenly she might criticize herself, there was nothing to be done but see it through.

It was amazing to discover that Christopher had no part in ‘Usness.’ If she had not known it with Bruce she would never have been certain, and even now she doubted. Possibly she was thinking on erroneous lines — she was no expert thinker — but she could only go on, or rather let the thoughts run through her mind in their own way. It was an unpleasant process, self-analysis, but it would have been less difficult if she had practised it earlier, if she had developed her self-education.

All this thinking took place at various times, and came to her in jerks, as it were, in disconnected images that arose spontaneously and imaginatively. It was the result of the mental disturbance caused by Bruce’s refusal to collaborate in the plan, and nothing could be done, one way or the other, until she had arranged her self-knowledge in some sequence and learned as much as was necessary to act upon.

Most of the process appeared to occur when she was alone, when she was doing her job, or resting after a swim, or just before she went to sleep, but it was going on all the time, consciously or unconsciously. Bruce watched, and let her be, till in due course she should make her decision known to him. Whenever she asked a question, whether apparently connected with this one problem or not, he answered her as impersonally as possible. She could have been influenced easily enough — but success so attained would have been of no use, either to him or to her. For the rest, they talked mostly of the ‘things’ they both cared for, leaving ‘people’ alone as much as possible.

Why had Christopher no share in ‘Usness’? Because, so it came to Nicolette one night, he was eternally looking for Meaning. These intimate sensual satisfactions were either the only expressions of meaning or they were nothing. Nicolette found it hard to define this. But she tried to put it in terms of her very elementary knowledge of physics. All these small things that through the senses and nerves and memory conveyed these big emotions were each one of them just a complicated arrangement of quantized electrons and protons. When one thought of small things so, it was quite pleasant, but certain people, like Christopher, could not bear to apply their minds to the conception of these whirling and dancing charges in large groupings. Size, after all, was just a quantitative conception, but one which very few people could face with equanimity. Nicolette was one of these people, and so was Bruce. They were not troubled to find out mystical meanings, to wrench a god concept from the stars, to insist on the hypothetical existence of a plan or pattern that could be apprehended by human intelligence. Such a conception seemed to them to matter hardly at all; as little as they themselves ‘mattered.’ But to Christopher and to many men who had preceded him, nothing else had ever really mattered.

Why then had she joined him in his gestures of antagonism to the community, and been willing to be his tool in his attempt at revolt? Whatever explanation she might be able to advance for this would, she guessed, appear illogical and unintelligible.

Well, she had loved him and she knew him unloving, yet dependent to an indescribable degree on this loving atmosphere, no matter whence it emanated. People, women especially, always loved Christopher. There were Antonia and Emmeline and Morgana besides herself to love him, and even, probably, Lois. But whatever quality of love they had been prepared to give, only her own appeared to be what he had needed, the affection of which he could avail himself in order to thrive….

Then there was fun in defiance, and there was particularly the need to get, without even knowing just what it was, the kind of love she wanted. Others should perhaps have been able to provide it for her; perhaps not; in any case, she had had to seek for it in her own way, no matter how crooked and curled and apparently abortive a way that might prove. Nicolette knew now that what she had found was not what she had thought herself to be seeking; but she had no doubt at all that ‘it’ was Bruce, and their future life together, and the continuance therein of ‘Us-ness.’ She decided that it was futile to endeavour to think about it in rational terms, since she had neither the means nor the method, and since — she was honest enough to be candid with herself about this — the whole matter was one over which she had no voluntary control. Life might have ‘Meaning,’ but since, senseless or sensible, its imperatives appeared to be unescapable, she would leave it at that.

RADIUM AGE PROTO-SF: “Radium Age” is Josh Glenn’s name for the nascent sf genre’s c. 1900–1935 era, a period which saw the discovery of radioactivity, i.e., the revelation that matter itself is constantly in movement — a fitting metaphor for the first decades of the 20th century, during which old scientific, religious, political, and social certainties were shattered. More info here.

SERIALIZED BY HILOBOOKS: James Parker’s Cocky the Fox | Annalee Newitz’s “The Great Oxygen Race” | Matthew Battles’s “Imago” | & many more original and reissued novels and stories.