MAN’S WORLD (20)

By:

November 22, 2024

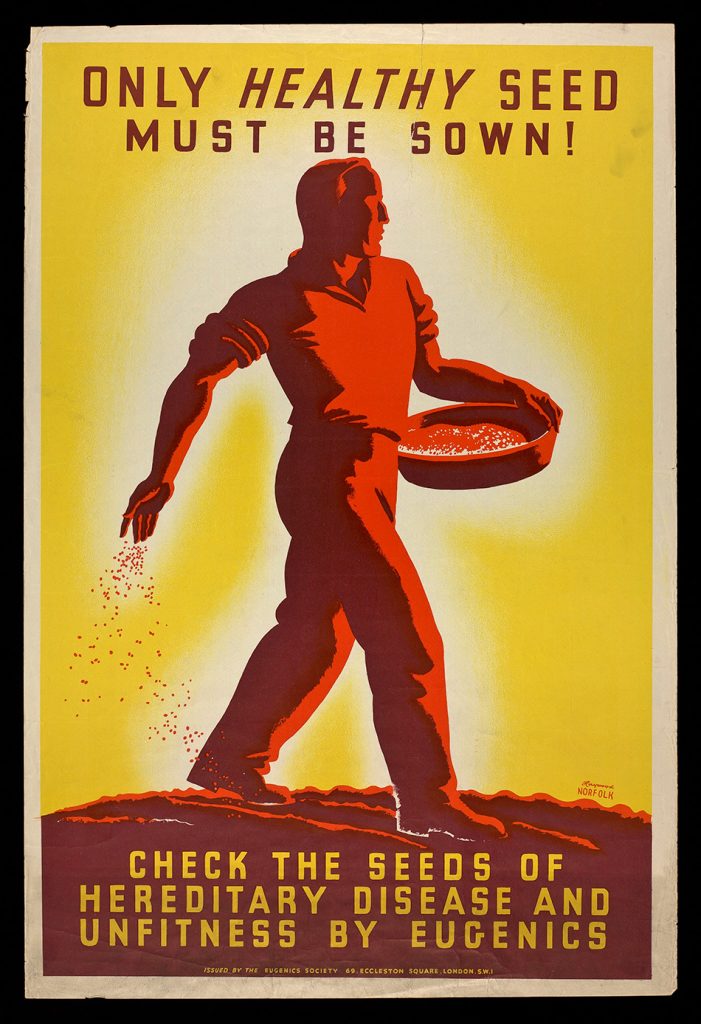

HiLoBooks is pleased to serialize Charlotte Haldane’s 1926 proto-sf novel Man’s World for HILOBROW’s readers. Written by an author married to one of the world’s most prominent eugenics advocates, this ambivalent adventure anticipates both Brave New World and The Handmaid’s Tale. When a young woman rebels against her conditioning, can she break free? Reissued in 2024 (with a new introduction by Philippa Levine) by the MIT Press’s RADIUM AGE series.

ALL INSTALLMENTS: INTRO | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25.

ANTIBODIES (cont.)

‘Certainly I do. Laws are merely formulae that we adopt to suit our own uses. The more efficiently we manage to state them, the more clearly we recognize their limitations. The laws to which man is subject apply to him as man, not as men. I can’t put it in English, but I can in German. Substitute “Mensch” for man and you will get my meaning. The laws they are trying to bend us to are all framed for men and women. The only law I recognize is that which governs the behaviour of human beings.’

‘God’s?’ suggested Christopher softly.

She looked at him for a second with wide open eyes.

‘If you will,’ she answered. ‘It is almost impossible to express what I mean except mystically.’

‘I’m all for the gods,’ agreed Arcous. ‘I know just what I stand for in this commonwealth. I’m only the foremost artist in it. I am just a pair of eyes, a pair of hands, and an æsthetic sense. So I don’t feel revolted as you do. I do my thinking vicariously. But I do it through you rather than through Adrian Richmond. Where there is neither revolt, nor mysticism, nor pain, there can be no art…. I am with you.’

‘I don’t want to be pushed nor will I be held back,’ declared Nicolette. ‘I seem to have known my way once, but I have lost it. I shall never find it again if I am not left alone.’

‘You must be left alone,’ exclaimed Morgana, and the three young men seemed, as she spoke, suddenly to edge forward round the two of them. It came like that, flashingly, a leap from vagueness to certainty. They seemed to have pooled their separate defiances, and now Morgana’s words had precipitated them into crystal clear resolution.

Nicolette must be left alone to find her way. Whichever alternative she should shortly be compelled to choose must not be, for her, the irrevocable one.

‘Yes,’ drawled Bruin. Something in his own line was to be done, and he was all awake now to devise the means. ‘Are you prepared to be immunized?’

‘If I am obliged to make a decision,’ answered Nicolette slowly, ‘yes.’

Arcous tried to keep the gladness out of his eyes.

‘Can’t anything be done about it?’ Morgana’s impatience made no impression on Bruin. He rolled on to his back, pulled a tuft of grass, and munched it slowly.

‘Possibly,’ he said at last, with his eyes on the sky. ‘I have heard rumours…. I might be able to get you some stuff to push in first…. I should have to make a trip abroad for it, though.’

‘I’d go,’ volunteered Christopher.

‘No use, my boy. Too technical for you, this job. Of course,’ he said, turning to Nicolette and peering at her over his own large body, ‘you’ll be taking risks, you know. Either way. Do you realize that?’

‘Of course,’ she emphasized his words. ‘But let us say we’re collaborators. We shall all find out something we rather desperately want to know, shan’t we? For me it seems the only way, and for you there doesn’t seem to be another, does there?’

Her words and her glance were for Christopher, and he answered both as was expected of him.

‘There does not,’ he said quietly.

Arcous smiled and murmured: ‘Vive l’anarchisme.’

‘If you want anything really reliable,’ had said Bruin’s friend, ‘I advise you to go to Monailoff for it. I haven’t time to make the stuff, and also, though I’m with you theoretically, I had rather it were not traced to me, if anything unusual is going to be done. You can have all the references I’ve got, but they don’t amount to much. The last man to do anything with it was Schier, in 1942. But I don’t think there’s ever been an experiment on a woman. Magdalens don’t turn Marys as a rule.’

It was some time since Brian had seen his friend Monailoff, and he had never met Bruce Wayland, whom he found with him when he got there. Bruce was rapidly acquiring world fame; not so much because of the things he had done as those he had caused his ‘young men’ to do. His own work was drawing him daily further from the laboratories, but he never lost touch with them. His imaginative qualities and his daring, tempered by practical knowledge, drew these young men to seek the advice he never withheld. They took their dreams and their ambitions in all their crudity to him and laid before him their most secret aspirations. All that to the orthodox would have appeared most ludicrous and fantastic, Bruce considered with the cool imperturbability he would have applied to the most conventional of problems. You could not shock him, for he had no mental and few physical prejudices. So the young men came unafraid, and departed comforted. Occasionally one of them, acting on his suggestions, accomplished a bit of brilliant work, that would never have been tackled without his advice. Then the rule-of-thumb men made unpleasant remarks, and the number of Bruce’s youthful worshippers increased tenfold.

But if Bruce was a torch-bearer, Bruin was an explosive. In the ordinary way of work he was noted for an impeccable reliability, a man to be trusted with the most delicate and complicated jobs. Not very inventive, they said of him, but unrivalled in his own line. His ability, within certain definite limits, was taken for granted. No one, except Morgana and Arcous, had probed further nor attempted to find out just where his limits lay, and being a taciturn fellow with an obsession, he volunteered no information to those who did not ask for it. ‘I’m only doing the opposite,’ he had said reproachfully when, as a small boy, they had found him walking on his hands with his hat on his feet. And to do the opposite, in the laboratory, was his obsession. Whenever and wherever possible he reversed every process he carried out. Gradually the obsession led to a vision, which, like all visions, had in it something sublime and something ridiculous. He himself, having no personal ambition, mocked the absurdity and affected to despise the magnificence. But Morgana egged him on, and, caring intensely as he did for her respect, he played with bits of his vision occasionally, to give her pleasure.

The scientific commonwealth was founded on force, as it had to be for self-protection. Bruin was one of those violent pacifists for ever chafing under the restraint they impose on their own brutal tendencies. And as an outlet for these he began to criticise, to disparage, and finally to condemn the social order of his day, built, as it seemed to him, on an ignoble foundation. But only a trained psychologist, a trained chemist, or a trained physicist can combat with any chance of success such trained opponents. As previous wars had become increasingly problems of scientific invention and management, fought with weapons with which perhaps half a dozen men had supplied millions, victory inclined invariably to those nations who could supply the men of finest scientific skill. It was a question of finding counter-weapons more certainly than new ones; as he had said to Arcous, ‘For every one of theirs one of ours.’ And so, in secret and purely for fun, he studied this matter of providing them.

In his case it was a harmless hobby, hardly likely ever to become a dangerous pursuit, for in spite of Morgana’s passion for intrigue and lust for power, Brian did not take it very seriously. He knew that such a task as his could never be carried out on a scale large enough to loom menacingly before the Leaders; and apart from technical difficulties that were insurmountable, the vigilance of the Patrol was as efficient as became so proud a body.

But one could do little things. Personal liberty, within the defined limits, was considerable, and was apportioned largely according to the intellectual merits of the person concerned. There were loopholes, and particularly in regard to precedents, for the unusual will always remain the unexpected.

Brian was willing to be of assistance to Nicolette because he had a sympathy for Morgana’s point of view, and what he might not have abetted in her case, he would in that of her friend. He considered Nicolette, as they all did except possibly Arcous, destined ultimately for motherhood. She appeared to him as the exception among women, in whose case the usual precautions might well be waived. And the experiment in itself appealed to him irresistibly. Hers might be a test case of considerable interest, and should, therefore, be proven. He knew that the authorities would look upon this, as on all exceptional behaviour that involved general issues, with disfavour; nevertheless, having no intention of contributing personally to any future experiment in parenthood she might make, he considered his share of providing her with a means to evade immunization justified on objective grounds. And Brian too was brave and admired courage.

The conversation with Monailoff was strictly technical.

‘I can let you have the stuff in about a month,’ he said, ‘if that will do.’

‘Excellently. She still has two at her disposal.’

‘Do you think she will carry the thing through?’

‘One cannot tell, but it is extremely likely. It is a matter in which the brother will have considerable influence.’

‘How So?’

‘He is a mystic with a strong inclination towards martyrdom. He cannot find a medium himself, so he will probably urge her towards the complete self expression that is denied him.’

‘What is he likely to do if her irregularity should be discovered?’

‘Take the entire responsibility on himself and fight the authorities on her behalf. It would delight him.’

‘Have they any adherents?’

‘Not at present. They have no programme, you see.’

‘I do. Who can have, nowadays ? I think for that very reason our civilization is marching rapidly towards its end. Remember the words of that earlier mystic: “Earthly excellence can come in no way but one, and the ending of passion and strife is the beginning of decay.”‘

Bruce entered at that moment, eruptively, in his usual way, and having heard only the quotation immediately retorted: ‘If conflict really is an integral part of nature, surely we shall see conflict in man and between men develop in new directions as we rise in the anthropological scale.’

‘It is to be eagerly awaited, if you are optimistic enough to think so,’ answered the other.

‘Certainly there seems small chance of such educating conflicts at present. That is why,’ he turned to Brian, ‘I will do what I can for your friend. May I tell Wayland what you want? He is always suggestive.’

‘Certainly,’ answered Brian, ‘if you think the matter sufficiently important. It may not interest him.’

‘Everything interests him,’ said Monailoff with a smile. ‘Particularly biology. He wants,’ he explained to Bruce, ‘some anti-immunizing substance, that will combine with Sp.902 before it reaches the female tissues. I think I can make it for him.’

‘That is interesting,’ boomed Bruce emphatically, ‘and just the sort of thing I should have expected him to come for. I think your notion is quite sound, but I should be inclined to — incidentally,’ he turned and smiled on Brian rather mischievously, ‘may one ask whether you propose to carry out a practical test?’

‘Decidedly,’ replied Brian, pleased with Bruce’s instantaneous appreciation of the situation. ‘But my share in it will be confined to this mission, and to injecting the stuff when I’ve got it. Whether the experiment will be carried through in toto I cannot predict. That does not rest with me.’

‘Oh, but it must be,’ said Bruce, to whom the audacity of it appealed. ‘I am willing to volunteer myself to oblige the admirable young woman. The point is, of course, whether one should ask permission first, or go ahead and wait for trouble afterwards.’

‘Why should there be trouble?’ asked Monailoff. ‘It will a be a valuable experiment.’

‘Scientifically, but hardly socially,’ retorted Bruce.

‘You do not quite understand race psychology in these matters. Especially of the woman. If you invent a biological religion, as we had to do for them, and call it vocational motherhood, heretics will be as surely attacked by the female inquisition as Protestants were by the Catholic one. Remember that women, broadly speaking, are always a century behind men in mental development. This will lead to quite an interesting situation.’

‘If it leads to anything,’ said Brian.

‘Oh, it must. It would be a pity to be inconclusive in such an excellent test case. Lots of us think things want stirring up. This will provide us with a useful ladle. But your young woman must have considerable pluck if she is going through with it. May one know more about her?’

‘I hardly think it necessary, at present,’ answered Brian, as cautious as the beast whose name Arcous had bestowed on him in fun. ‘Later perhaps, if anything comes of it.’

‘Well, you can depend absolutely on me if you want assistance in any way. I shall be in Nucleus in three months’ time, and will call on you to hear how matters have progressed. In the meantime,’ he added with a grin, ‘I’ll look round for a suitable young man to assist in the next step, should one be required. Remember me to Morgana.’

Once the decision was irrevocably taken, all the torturing doubts were, of course, Christopher’s. This method of defiance was, after all, a new proposition. It was by no means entirely their own. Neither of them knew enough about biological technique to have devised it themselves. It had been evolved by the council of five. Arcous, the sly catalyst, had pushed them to a certain point, and there they had met Morgana, who had added her feminine touch to a revolt that, as it had lain in themselves, was hardly at all sexual in principle; and with her was Brian, the ready instrument to help carry out the joint purpose.

Nicolette was delighted and almost surprised at her luck. Things had at last been straightened out. She had stood so indecisively at the parting of the ways, between motherhood, for which something deep within her still craved in rebellious, crooked, yet clamorous fashion, and that other life of the mind and the senses in which Arcous would loom as large as Art, and from which she seemed to shrink almost as keenly as she was drawn to it. The picture of the wider implications of what she was about to do hardly touched her imagination. She felt that perhaps it might be symbolic, but that side of it seemed more a matter for Christopher to deal with. All she realized vividly was that she would be given a respite, that the irrevocable decision would be postponed, and she expected fervently that within a short time she would be shown clearly which path to choose. Nor would it, so, be too late to turn back. Although the word had no place in her vocabulary, Nicolette hoped (how she hoped) for some one to claim her at last.

Christopher looked further and with a greater dread. He was honest enough and brave enough to realize that once the lawless step taken, he would be tempted to make a tool of Nicolette, to use her as his weapon. Never for a moment did he doubt that her mating would be long delayed; he foresaw the consequences, and what they would mean to him as well as to her.

‘Are you quite sure you want to chance it?’ he asked her more than once, and always she replied: ‘Wouldn’t you?’

‘That’s just it. I feel it’s up to me to do something, and not to let you do it for me.’

‘But I’m not committing myself. That’s just the beauty of it. I’m only taking a precaution in case I should wish to later.’

‘Oh, it’s an opportunity you’ll never be able to resist. It’s the sort of thing I should be doing myself; striking a hefty blow for individualism. And all I can do is to egg you on.’

‘But the whole experiment may fail,’ protested Nicolette, though she did not herself believe this. ‘Even if it does not, I don’t see what equivalent thing a man possibly could do. Anyway,’ and suddenly she went and laid her arms about him, and pulled his head down to her own, ‘whatever is done we do together, my dear. The deed might be mine, but the will to it, like all my resolutions, comes from you. There is no point in attempting to separate our thoughts and actions. They are inextricably united.’

Then Christopher almost wished she would do nothing, after all. For if she did, it would be clear evidence that she could love another as she loved him, a possibility he could hardly contemplate with equanimity.

It was not even necessary for him to advise on Nicolette’s future employment. The temporary arrangement with Weil had proved very satisfactory. In addition she could make herself socially useful in a score of ways, for she had a mind for detail as well as considerable patience.

But particularly Nicolette wanted to enjoy herself. She felt conscious of a change in her mind and body during the past months. The’ growing pains’ seemed to have ceased; she felt happily sensual, healthily vigorous. Her perception seemed to have become sharpened; her pleasure in all things was rich and keen, there was now a shining about her, a lustre, which even the dullest among her companions noticed, and which entranced the artist in Arcous to the point of intoxication. This was particularly remarkable when she was with Morgana, whose vitality was mainly nervous, whereas Nicolette’s was a spontaneous sparkling up of youth towards beckoning experience.

Notice of her decision had been formally sent in to the council. Her secession, since she had definitely chosen her future way, was now merely a matter of routine. Whatever impression it may have created in the minds of those women who had previously endeavoured to persuade her otherwise, was not now voiced, since discussion of an accomplished fact would have been futile.

Until after her immunization, however, she would still be subject to tutelage. So it was that she remained in the little room that had housed her more or less continually since childhood. In response to Morgana’s invitation, she frequently visited her and Brian in the laboratory where they worked together.

There, one afternoon, she bent over a microscope, keeping her eyes on the slides they slipped in for her to look at, while Brian spoke softly, his head close to hers.

‘I have got the stuff,’ he said. ‘It has just reached me. Do you think you can push it in yourself? ‘

‘Oh yes,’ she answered, ‘quite comfortably.’

‘Well, do it intra-muscularly,’ he advised. ‘I think that will be the most efficient way.’

‘I’ll bring it along,’ added Morgana, ‘so that you can do it just a few hours before. It will be wise to wait as long as you can.’

‘I want to warn you, though,’ added Brian, ‘that there’s a certain risk attached. What I propose to do is to jam your immunizing mechanism pretty thoroughly. The effect may last for a few weeks, and during that time, if you get an infection of any kind, the consequences may be unpleasant.’

‘I’ll chance it,’ Nicolette answered calmly.

‘Right-o. The stuff has been used before on rabbits and guinea-pigs and a few monkeys, but never on a human being. So I’d be glad if you’d let me know whatever you feel in consequence, though there’ll probably be nothing exciting. If you feel especially uncomfortable, let one of us know.’

‘I will. What a pity you cannot publish a paper on it.’

‘Oh, there’s nothing in this part. The sequel — that remains to be seen.’

‘I doubt whether I shall worry much about it yet,’ Nicolette answered with a smile. ‘I shall be so busy in the next few months.’

Brian glanced at Morgana, but neither of them spoke. It seemed so obvious that a sequel was inevitable. As physiologists, they disliked inconclusive experiments.

Morgana had packed it all up in a neat little case: alcohol and iodine for sterilization, hypodermic syringe, and a small glass-stoppered phial containing the precious fluid. The look of the utensils pleased Nicolette. There was always something so trim, so clear-cut, about this kind of apparatus. These people who worked in labs. surely must take pleasure in the mere handling of their instruments. It was not her line, but even she could respond to their stimulation. All tools were more or less the same, of course, in this way. Whatever art or craft they might serve, always they seemed honest and willing agents to carry out the purpose of the master-mind. Slowly and carefully she bared her thigh, applied the iodine, dipped the needle in alcohol, and then at the pressure of her finger watched the pale fluid jump from bottle to hypodermic. Now she tossed a curl off her forehead, bit her lower lip in the intensity of her concentration, and with a firm gesture stabbed her smooth tinted flesh. She sighed a deep sigh of relief when it was all over, but she did not notice it. She had been bent on the job.

Christopher asked nothing when they met in the hall. He was waiting by the letter-rack, where a blue slip lay in her pigeon-hole. Nicolette tore it open, glanced at a date, and handed it to him.

‘To-morrow morning,’ she said laconically.

He raised his eyebrows; she smiled at him quite gleefully, but he did not return the smile.

She tucked her arm through his, and felt that he was trembling.

‘Let’s fly,’ said Nicolette.

Once, in the dim days of the late nineteenth century, a noble ancestress of Nicolette’s had run away from home and gone on the stage. She had not previously announced her decision, but in any case, the blow to her parents would have been unmitigated. She did not gain much theatrical success, but, having met several duchesses, she could look and speak like one. A young peer, to whom this achievement seemed, from the stalls, more remarkable than it was, married her on the strength of it. Nevertheless, her family were irreconcible. If her parents could have frustrated her desertion by shutting her up in a convent, they would at least have had the pleasures of revenge. Antonia suffered somewhat as they had suffered when at last the impossible was about to become fact in Nicolette’s case.

Fidelity to custom embitters most women’s lives from time to time, but never more keenly than when their daughters defy it. Customs may change, but fidelity is a clinging habit. All the unpleasant emotions which had assailed poor Lady Geynes when Marcia revealed herself were reproduced in the unfortunate Antonia when Nicolette, shortly before attending the council, proclaimed her intentions. It seemed so ‘unnatural,’ and the limit of the most understanding creature’s sympathy is usually reached at the ‘unnatural.’ Antonia’s disappointment was, like all of its kind, more social than personal. The caste instinct was powerful within her, and she resented far more the blow to her ambitions than the frustration of any grandmotherly yearnings. As was to be expected, she sought reasons for her daughter’s behaviour in every direction but the essential one, and her resentment finally crystallized in antagonism towards Emmeline, to whose sinister neuter influence she attributed her daughter’s decision. Dominated now by her repressions, it did not occur to her to hold Christopher responsible.

Antonia’s mistake was fortunate for Nicolette. For incontinently she had dashed with her tale of woe to St. John, compelling him, for one whole quarter of an hour, to desist from his great problems in order to concentrate on this small one. But St. John’s respect for Emmeline was firm. It was based on a just appreciation of her splendid qualities, revealed during years of reciprocal labour in the cause of humanity.

‘I will certainly see Nicolette if you wish,’ he told Antonia, ‘if she has anything to say to me in the matter.’ Rationalization of the paternal instinct was neither the fashion of his day nor of his temperament. The question of Nicolette’s future lay entirely outside his province; it had no more concern for him than would have had the similar problem of any girl in her position.

She saw him one day, as she was strolling alone along a shady avenue that led from Nucleus to the hills. St. John had always been a prodigious walker, and his twenty kilometres a day had become a firm habit. He was returning now to tackle the evening’s work, which would consist of several intimate conferences, a semi-public debate, and he knew not how many hours of subsequent dictation. She resolved not to approach him, for she knew that on these walks he worked out and reviewed decisions to be carried out later on. It was, moreover, a matter of etiquette not to accost any one out-of-doors without encouragement. She turned, therefore, in the same direction, leaving him to overtake her and to speak if he wished.

‘Why, yes, of course it is — Nicolette.’ He smiled down at her with his usual rather vague cordiality. She fell into step with him then. ‘I seem to remember,’ he continued, ‘that we were to have had an interview. Why not now?’

‘Certainly,’ she answered, smiling back, ‘but what about?

‘Don’t ask me! Was I not to have been consulted about your future career, or something?’

‘Possibly, but not by me.’

‘Excellent. You obviously are my daughter. Then I take it you have decided all about it?’

‘Momentarily, yes.’

‘That is very satisfactory. Go step by step. I am sorry we do not meet more often. But keep your sense of perspective. Nothing is more absurd than the human tool which imagines itself the master. Really fine tools are rare, we know, but most sort of instruments can be turned out pretty easily. The idea is the hand that wields them, but the force behind it is as inaccessible to our understanding as the mind of a sculptor would be to a chisel. There is no direct contact. Ideas, abstractions, are all we can know; therefore they are all we need bother about. Our job is to be instrumental in turning them into action. But don’t imagine for one moment that individually you are more than an instrument. Oh, the trouble I have in persuading some of my colleagues that they are not the commanders of the universe.’ He sighed comically. ‘And even more, that it is not their business to ask who or what is. What does it matter, so long as there is something to be done.’

‘But is there?’

‘What an admirable young woman you are! You feel like that too, then, do you? Well, on the whole there probably is; at any rate, there is a certain amount of evidence of a scheme of sorts going on. But don’t imagine for a moment that you can either assist it or thwart it to any considerable extent.’

‘But some people are not content with that; they want to know more,’ replied Nicolette, thinking as usual of Christopher.

‘Well, tell them from me they won’t,’ he answered kindly, understanding her hidden allusion. ‘Though the curiosity is an admirable thing in itself, as a basis for action later. You know the majority of people unfortunately become stabilized at an early age. They are a nuisance, and in extreme cases a danger. A certain minority, on the other side, are victims of a permanent instability that may become equally troublesome, though they are far easier to deal with. The people we want nowadays are increasingly those who will remember the word that should be the hall-mark of all government, all education, all human thought, in fact; the word Provisional. With that constantly in view, you can settle down to anything comfortably and usefully.’

‘Have you been studying Publicity?’

‘Yes; I’ve been having a look round. I’m increasingly dissatisfied. Just at present I can discern a growing hardening everywhere, and a proportionate move towards stabilization. It won’t do. It is spreading; creeps right to my very door. I have to walk like mad to get away from it occasionally; to let ideas shake me up and keep me flexible. And then back again to the daily task of shaking up others. Well, here we are. I’ve been delighted to meet you. Whatever decision you take, be certain it’s a satisfactory one. Remember me to your brother.’

As he ran up the steps of the Council Building he thought: ‘Curious, one’s children. Sometimes they’re so nice.’

And then forgot all about them.

RADIUM AGE PROTO-SF: “Radium Age” is Josh Glenn’s name for the nascent sf genre’s c. 1900–1935 era, a period which saw the discovery of radioactivity, i.e., the revelation that matter itself is constantly in movement — a fitting metaphor for the first decades of the 20th century, during which old scientific, religious, political, and social certainties were shattered. More info here.

SERIALIZED BY HILOBOOKS: James Parker’s Cocky the Fox | Annalee Newitz’s “The Great Oxygen Race” | Matthew Battles’s “Imago” | & many more original and reissued novels and stories.