MAN’S WORLD (19)

By:

November 16, 2024

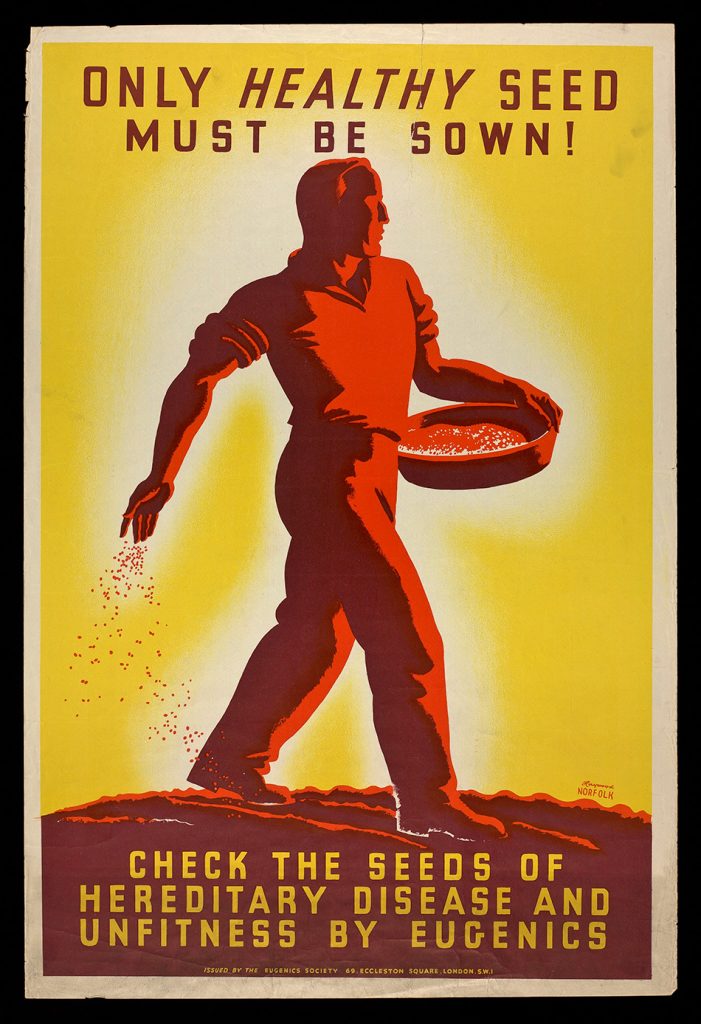

HiLoBooks is pleased to serialize Charlotte Haldane’s 1926 proto-sf novel Man’s World for HILOBROW’s readers. Written by an author married to one of the world’s most prominent eugenics advocates, this ambivalent adventure anticipates both Brave New World and The Handmaid’s Tale. When a young woman rebels against her conditioning, can she break free? Reissued in 2024 (with a new introduction by Philippa Levine) by the MIT Press’s RADIUM AGE series.

ALL INSTALLMENTS: INTRO | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25.

ANTIBODIES

You will not easily persuade me that man’s future will be less surprising and tragic than his past. J. B. S. HALDANE — IN A CRITICISM OF THE SYNOPSIS OF THIS BOOK.

Antonia was in for a difficult six months, and she felt aggrieved about it. The unadmitted cause of her annoyance was Claire Tamston, for whom she felt a daily growing antipathy. Claire never omitted an opportunity to inquire with affected interest after Nicolette’s welfare, and Antonia interpreted each inquiry as a renewed reflection on her own integrity. Claire was an abomination, with her self-satisfaction, her suspicions, her public spirit. But Antonia had been well disciplined and was no fool; she knew that the precept ‘Love thine enemies’ was the basis of all government by consent. In ancient days judges had worn in some countries special robes in which to preside in their courts. There was now no need for such childish symbols of auto-suggestion. Antonia as a member of the council was at her best, for she held that concord among arbitrators was the essential basis of justice towards appellants.

The self-discipline she practised in public, however, was not proof against a certain irritation in private. Dignity had demanded of her that she should formally agree to supervise Nicolette’s activities, but this was an unexpected task which had been thrust upon her by her own loyalties. Antonia and St. John had met but twice within the past month; she was used to making her own decisions without reference to him, but in this matter she would have welcomed his advice.

She felt that Nicolette had put her into an old-fashioned and slightly ridiculous position. It was absurd that she should require supervision at her age, and at a period when maternal authority over children other than babies had long been abolished. Yet in view of the laws of the day it was obvious that a girl dedicated to motherhood, and in whose case immunization had not even been mooted (Antonia shuddered when she thought of that horrid possibility), must not run the slightest risk of contamination.

Then she remembered Miomi’s wise words, and took comfort. The obvious thing to do was to find a mate for Nicolette as soon as possible, a lover whose kisses would plead more eloquently than a mother’s words could do. Antonia was reserved even with herself on the subject of sex. It did not give her much pleasure to review her own girlhood and early womanhood. There are pages in such reminiscences even the bravest women, and men too, hesitate to reopen. They contain records of so many slight disloyalties, false ambitions, and mental, if not physical, seductions. Antonia had censored a few of hers many years ago; the rest she had by now managed comfortably to forget and if ever she had known qualms when she recalled her behaviour during Christopher’s pre-natal days, she had long come to regard herself as the pattern of devotion to duty.

It occurred to her that Christopher might be helpful in dealing with the present problem. It had occurred to him too — although from a different angle.

The ‘two children,’ as she called them (though she never thought of her others as un-grown-up), had come to see her one evening.

‘How splendid you look, Nicolette,’ she said, observing with pleasure the change in her daughter. The second softening, into young womanhood, was beginning to round out Nicolette’s long delicate outlines now. Her thick curls were tinged with a lovely nut-brown gloss, the eager eyes looked out softly and happily from between their long lashes. Her small breasts, thin arms and legs, were swelling into the first perfection of maturity. It was obvious to others besides Arcous Weil that she would soon be an exquisitely beautiful young woman.

‘I’m contented,’ she answered with a joyous glance at Christopher. ‘I love working with old Weil. I could go on like this for ever.’

‘But that won’t be possible, you know,’ Antonia admonished gently. ‘You will dislike me if I always pull you out of your day-dreams, but you must think of your future.’

‘Oh, well, I have five and a half months before I need do that,’ Nicolette replied flippantly. She simply could not take Antonia seriously.

‘But I have not. Don’t you realize, they’ve made me more or less directly responsible for it? It’s a most curious position to be in.’

Nicolette looked sharply at Antonia and began to have some glimmerings of her dilemma.

‘I beg your pardon, you dear,’ she said, suddenly sitting upright, for she had been lazing on some cushions. ‘It is hardly fair of me, is it?’

‘Oh, I know you never meant to give me any trouble’ please don’t think I am complaining,’ answered Antonia, responsive to her amiability. ‘But I don’t want you to lose yourself entirely in those workshops. You know there is nothing I want to do less than supervise you as if you were a small child, but the position is unusual. You obviously cannot go about among a lot of Neuters and Entertainers as if you were one of them; you must have some kind of a chaperon.’

‘She has, already,’ put in Christopher soothingly.

‘Whom?’

‘Me. And if I won’t do, what about Emmeline? She could replace you whenever you like, you know.’

‘Oh, I trust you absolutely, both of you, you know I do,’ protested Antonia, a little emotionally. ‘But it would be so nice if you could form a group of suitable young people of your own age.’ (Back of her consciousness she felt the disapproving eyes of Claire Tamston looking on a shade less harshly.) ‘What sort of young men do you like, Nicolette ?’

‘I only know one at the moment who attracts me in the very least,’ Nicolette answered dreamily. Antonia’s face lit up with eager anticipation.

‘What is he like?’

‘An adorable creature. Tall, fair, thin, but thoroughly healthy, clever, quick-witted, sensitive….’

‘How old is he?’

‘A little older than myself.’

‘What does he do?’

‘He’s an artist.’

Antonia’s face fell a little.

‘Oh! Has he been mated already?’

‘You might ask him. He hasn’t told me so.’ She smiled maliciously at Christopher, who grinned back at her from behind their mother.

‘And you like him?’

‘More than any one in the world. I’m already mated to him in affection.’

‘What is his name?’

‘The same as your own.’

Antonia’s brightness faded out like a light switched off. Yet she could not help smiling plaintively as Nicolette and Christopher burst into peals of laughter.

‘You little wretch!’ she lamented.

‘Whose fault is it?’ asked Nicolette, still malicious. ‘You give me a brother with whom I’ve been in love since childhood, and then you expect me to mate with the thoroughly unattractive youths produced by other people. You ought not to have set me such an excellent standard.’

Antonia could not scold; could not help feeling happy and proud when she looked at them sitting there before her, side by side. ‘The two children.’ Hers — how utterly and unmistakably hers!

‘Well, then, it’s up to Christopher to find a mate for you. If he approves of the young man, you will.’

‘I’m not sure I want to,’ said Christopher slowly, his arm around Nicolette, his eyes on Antonia.

‘Oh, Christopher, don’t you make a fool of me now,’ she pleaded.

‘But I’m in earnest. I don’t want her to mate; at any rate, not yet.’

‘Christopher! How can you talk like that? How perverse you are! Is it possible you have been encouraging her in this ridiculous refusal?’

‘There was nothing ridiculous about it in the first place, except Raymond,’ he declared frankly. ‘Why should Nicolette do as every one else does? I did nothing for years, and they did not touch me, nor did you try to coerce me.’

‘But that was utterly different!’ she almost moaned.

‘Look here, mother,’ and Antonia paid attention now, for he never used the filial expression unless he was quite serious, ‘how do you know that we are not both “different”?’

He paused for a moment to allow her to appreciate his point. But Antonia was too practised a skater to fall through that thin ice. ‘Have you never felt a little — well — perverse, yourself? Why do you expect Nicolette to conform so completely to the mean? You may have been able to do so, perhaps, but you know very well that there is something “different” about me. Why not then about her?’

‘But you are an artist, my boy. You will be a famous man one day. Nicolette shows no sign of any talent like yours.’

‘Because she has never had the chance. You specialized her training so early. Supposing you had been on the false track from the beginning? Supposing she cared for music as much as I do, and wanted to do something else instead of breeding?’

‘I am certain she could not do anything so successfully,’ answered Antonia obstinately. ‘What talent has she?’

‘Her voice, for instance. I think that with training it might be an exceptional one. Have you ever thought of that?’

But Antonia had not and did not intend to do so now. His last words had suggested appalling possibilities. Immunization…. As usual, she refused to contemplate unpleasant prospects.

‘I refuse to let you suggest such silly ideas to me,’ she said, and they both saw her frightened, absolutely resolved that the subject should not be pursued; ‘and I beg you not to suggest them to Nicolette. She should at least have every opportunity to find a mate who appeals to her — mentally and physically.’

‘By all means,’ he soothed, knowing that he had gone rather far with her. ‘But you must realize that she is not to be coerced, and that if there is danger of her making a mistake, it is because of the mistakes that have already been made. Let her be as free as possible during the next few months. It is the least any one can decently accord.’

‘Certainly she shall have her way for the time being,’ answered Antonia, who had made up her mind to discuss the problem with St. John at the earliest opportunity, and also to talk to Emmeline, who had obviously been encouraging ‘the children’ in their perversity.

Nicolette now lived almost entirely out of doors. Although she and Christopher had always spent long hours together in the open, there was a definite reason why they did so at present. Away from buildings they were away from people, and on their walking, flying, riding, or swimming expeditions they could take the companions they chose without provoking unfavorable comment. Arcous was nearly always with them during his leisure, but he quietly attached himself more closely to the brother than to the sister. And he began to surround them, very carefully and casually, with one or two intimates of his own.

There was Bruin, whose name was Brian Keck. Arcous had early wished to make or to supervise the making of his own colours, and for this purpose he had taken a course of synthetic chemistry. During the time he had spent in the laboratories, he had come across this fellow on one or two occasions. Bruin was rather fat, he had a longish thick nose and small brown eyes set very close together. His body was covered with hair which he systematically destroyed with depilatories as soon as it grew, because he admired a smooth skin. A faint odour of sulphur seemed always to hover about him. Arcous and Bruin admired one another profoundly. Neither took the slightest interest in the technical side of the other’s work; sheer force of one strong personality attracted to another pulled them together. But Arcous did know that Bruin had the same love of power as himself, and that he cherished strange dreams. Bruin was destined for Christopher.

There was Morgana Dietleffsen, who had chosen that personal name because she was a distant descendant of Morgan, the famous geneticist. Morgana was a tall fair girl whose features were not beautiful, but the blueness of her eyes and the scarlet of her lips were unforgettable. She lived with Brian, but really loved Arcous.

The five of them had climbed one afternoon to the hermitage of the old Extonian. He was Alexander Murray, the only survivor of the obliteration of that doomed community, but he had not escaped unscathed. He was a famous entomologist, and the scenes he had witnessed there had mingled disastrously with impressions of years of observation of insect life. They attached superlative importance in the state to the lessons of entomology, so that his marked idiosyncrasy was tolerated. He had established on the top ofhis hill a magnificently equipped laboratory, surrounded by open-air reservations wherein millions of ants and beetles could be experimented upon under ideal conditions. Christopher, Bruin and Morgana knew the place well; Nicolette and Arcous had not yet been there.

‘You won’t see Murray himself, of course,’ Bruin told them as they set out on their tramp of twenty-five kilometres. ‘No one ever does except his assistants, and they invariably ignore him. For the past thirty-six years he has completely broken off diplomatic relations with the rest of the human species. He has to lecture once a month by radio; that was the sole condition imposed on him when he came here; for the rest his only companions are his bugs.’

‘What is the matter with him?’ asked Nicolette.

‘Megalomania. He’s an authority on Parasitology. He was in Exton, all those years ago. He wrote his most important books during the last years, between the assassination of Goldring and the final obliteration. Even then he was not communicative. He travelled all over the world, and would only come back from time to time in order to put his collections in order and write his observations. He never was interested in men, and he was almost entirely ignorant of what was taking place around him. When the end came, the Patrol warned him to clear out. He was the only person there they wished to spare. He came here and has lived on the top of his ant-hill ever since.’

‘What was the real story of Exton?’ Arcous asked. ‘I have heard about it vaguely, of course, but I have never bothered to read it up.’

‘Oh, it’s a marvellous story. The sort of thing that almost excites one.’

‘It’s the classic illustration of the power of the commonwealth,’ added Christopher. ‘I can’t recall a single other instance of such complete efficiency.’

‘There probably never will be another,’ said Morgana. ‘What fun if there were.’

‘Do not be so certain,’ said Christopher darkly, and Arcous glanced at him swiftly.

‘Well, let me hear the whole story’ — he turned impatiently to Bruin.

‘Christopher can tell it more fully than I can,’ answered the Bear, as he lumbered slowly uphill. He was already sweating and disliked exerting himself.

‘It happened as Bruin told you, just thirty-six years ago,’ began Christopher accordingly. ‘At that time the commonwealth had cleared up most of the obvious messes, but enough remained to be done in holes and corners to keep the Patrol interested in its job. Golding was at the head of it then, and it was organized as efficiently as the Spanish Inquisition had been. People had recovered from their first shock of surprise at finding that a scientific power, armed with invincible weapons, had come to replace the old nationalist ones. A few wars were still carried on here and there under various pretexts, because they were such a useful means of getting rid of the incorrigibles. Education was going well, the female orders were already established, and the dramatic example of the Gay Company fired the imagination of the backward.

‘But, as you know, there have always been certain races who were temperamentally intractable. The most troublesome of these at the time were the Celts. There were large numbers of them on this continent then, mainly descendants of the Irish and the Welsh. They tended to herd together in large communities. When they were not quarrelling among themselves, they loved to annoy those who came from outside to investigate and arbitrate among them. Exton was the biggest of these places. That was before the time when the relative sizes of the communities and the numbers of children annually produced in each had been fixed. There were several hundred thousand people in Exton.’

‘Help!’ exclaimed Arcous. ‘However did they manage to control them?’

‘That was the obstinate problem,’ answered Christopher. ‘They set up a strong Patrol committee at first, but that form of administration could not continue indefinitely. The whole point at the beginning, as now, was to create autonomous communities. So they decided to give them a chance. But the native Celtic slothfulness was too severe a handicap under which the new regulations had to start. Hygiene was almost impossible, and with the support of religion (or rather superstition) withdrawn, example had no force. The means were at hand, but not the morale. They had their hotels just as we had, but there was a constant battle to compel each of them to sleep in his or her own room.’

‘Surely,’ said Nicolette in amazement, ‘they were not so dirty as that! Do you mean to say that a man and a woman actually slept in one cot?’

‘Certainly,’ answered Bruin.

‘My dear, do you realize that in the twentieth century whole families still slept on the floor of one room?’ asked Morgana, who had studied hygiene and was well up in the subject.

‘No, I can’t,’ said Nicolette, so obviously disgusted that they all laughed at her expression of dismay.

‘Well, they did worse than that. In some places the pigs and the hens cuddled up with them.’

‘Spare us the more revolting details of ancient history if you can,’ pleaded Arcous, who shared Nicolette’s physical fastidiousness. ‘They remind me of the story of my immigrant ancestor, whom they found one day dipping his fingers in a glass of hot water. “What are you doing that for?” they asked, and he answered tearfully: “The doctor has ordered me a course of baths for my rheumatism, and I’m getting used to the water.”‘

Morgana was annoyed at his Jewish habit of self-depreciation. ‘I though your ancestors were Sephardim,’ she said, ‘and not Polish immigrants.’

‘So they were,’ replied Arcous with a smile, ‘but we all claim common descent from old Adam, and the mud of the Garden still sticks to us. Let’s get back to your black sheep, Christopher. They interest me.’

‘I made a slight mistake when I said that they no longer had the support of religion. Superstition and sentimentality still upheld them. That marvellous system alleged to be Christianity (of course it was nothing of the kind) still had a kick in it. They had to put up with Entertainers instead of “fallen women” for their sensual indulgences, but they found plenty of objects of pity and scorn to make a fuss over. Parasites of all degrees flourished on them. The Employment Councils had a tremendous job, because if a man would not work there was always another who was willing to keep him. They were excessively humane and had a horror of elimination. The duds lived longer than the honest men. At about this time old Murray came out of his trance. He had just been studying parasitology in the ants, and he took Wheeler’s fine passage for a text on which to base his parallel. Let me see if I can remember some of it… “Man furnishes the most striking illustration of the ease with which both the parasitic and host rôles may be assumed by a social animal!” …’

‘And,’ added Bruin, who suddenly stopped trudging uphill to turn around and declaim in loud dramatic tones, ‘Biology has only one great categorical imperative to offer us, and that is: “Be neither a parasite nor a host, and try to dissuade others from being parasites or hosts.”‘

‘Fine, fine!’ exclaimed Arcous enthusiastically. ‘Go on!’

But Bruin was fanning himself with a gigantic leaf.

‘You can look up the rest if you want to,’ he said abruptly. ‘I’ve forgotten it.’

‘Anyway, the old hermit hasn’t,’ said Christopher. That’s what drove him up here in the end. He wrote his first volume on the subject with the passion of a Jeremiah and the patience of a Darwin. Incidentally he destroyed another ridiculous illusion of ignorance: that the ants show an example that should be copied by man. It was one of those dangerous untruths that half-educated people were so fond of quoting. However, at the time his writings had little effect. They were too intelligent for those people, and he was already looked on as a harmless eccentric. They were hostile and, as far as they dared be, unkind to him.’

‘He was a Scot, you see,’ put in Arcous.

‘How these Celts loved one another,’ said Morgana.

‘Oh, not much less than the others, only they were more naïve about it,’ said Christopher. ‘You must remember that love was “done” or rather overdone, till it was assigned its proper place.’

‘Like a beefsteak that no one could stomach although they kept on serving it up,’ illustrated the irrepressible Morgana.

‘Shut up, Morgana, and let Christopher get on,’ said Arcous roughly. ‘We shall reach the top of the hill before he comes to the end of his story.’

Unable as usual to withstand him, Morgana obeyed.

‘They certainly wallowed in proteins and fat,’ said Christopher, ‘and it was almost impossible to get them to migrate and merge with other peoples, although that had once been such a pronounced Celtic character. But their decadence was incorrigible. At last the central executive became impatient with them and sent Patrolmen to investigate. Their reports were so serious that Goldring determined to go himself and make a clean sweep. He immediately set up a reformatory board. The psychologists were delighted, for they had never had such a complete case before them. But their joy was short lived. No sooner had they ordered a few eliminations and expelled the ring-leaders than Goldring was assassinated.’

‘How?’ asked Arcous.

‘Strangled by a religious maniac, O’Donnell. They got him, anyway, for the experimental work on stimulation of growth of brain cells in the adult.’

‘Mathias’s law,’ grunted Brian. ‘Most important.’

‘But what a job they had!’ continued Christopher. ‘Anyway, they managed to restore some kind of order for a couple of years. Fanniez had taken over after Goldring was moved on, and it was the sort of thing he liked. They did manage to infuse a little public spirit into a few of their more intelligent people, and they were just beginning to learn to rule themselves. Then came the climax.’

‘I remember about that,’ said Arcous. ‘The outbreak of infectious disease.’

‘Yes. A gorgeous mess. Imagine the sensation it created! First of all it began in other places, right along the trail from Chile, where the exiles had gone. It seemed to start in four places at once, and no one had the slightest clue as to its origin. All the victims were pronouncedly unstable types, so they were got rid of as soon as possible. Naturally, after all the years of freedom from disease of that kind, its appearance caused a certain amount of panic, particularly in the more advanced places.’

‘Nucleus escaped, didn’t it?’

‘Yes, happily our record wasn’t broken. It’s still intact. But that was entirely due to the fact that we didn’t lie in the lines of communication.’

‘Who were the carriers?’ asked Nicolette.

‘Four blighters who had escaped over the frontier and had managed to get smuggled back to Exton. Apparently they all had old mothers or some such Celtic witches who wanted to see them once again. The disease simply flew round the place. Nowhere in the whole commonwealth could conditions have been more favourable. To begin with, the people who had it were so annoyed at the though of being shown up, that they hid themselves and one another. That couldn’t go on very long, and they were soon spotted. All the women in the place were ordered to be immunized. Every child was cleared out to isolation stations. But although they might have got rid of the physical effects, the mental damage done was a different matter. The old slogan was dragged out of hiding too. “Disease is no crime!” and so on. There was a quite a little bout of mania again. The thing came before the Supreme Council, and even Mensch had to agree in the end that there was no alternative: Exton had to be obliterated. In any case, it simply was not worth keeping. So they went.’

‘How?’ asked Arcous again.

‘Oh, the usual way — smoked out like a rotten hive.’

‘And no questions asked?’

‘Hardly any; it was almost entirely a local affair, you see. Added to that there was universal indignation at the menace the Extonians had brought on the race. The collective conscience was beginning to work efficiently; the propaganda of the Company was bearing fruit, and the Patrol was trusted.’

‘What about old Murray?’

‘Oh, they had got him away some time before. He had gone into a slight frenzy when the disease first broke out, and imagined that he was infected with parasites, although he never got it. And that’s still the bee in his bonnet. He thinks that every one and everything is after his blood, and takes insecticide baths three times daily. But he still does work that hardly any one else could, they tell me. He has a superb technique after all these years.’

‘What,’ said Arcous, with his usual eagerness to probe Christopher’s mind, ‘do you really think about that wholesale massacre?’

‘I think,’ answered Christopher, ‘that it was a justifiable expedient, but a deplorable precedent. The so-called value of human life is always a debatable factor; its sanctity is a matter of sentiment, not reason. But if ever I think I would like to start a revolt, the lesson of Exton sobers me.’

‘That’s only a matter of weapons,’ answered Arcous, and called after Brian, lumbering ahead: ‘what do you say, Bruin?’

He turned round and glowered at them.

‘You’ve hit it,’ he grunted briefly. ‘Weapons are what we need. For every one of theirs, one of ours. Well, it might be done some time. Who knows?’

They had come to the top of the hill now, and began to approach the boundaries of the entomological reservations. Before them they could see the tiny hermitage that was the home of the old Extonian, and at a slight distance from it the substantial laboratories and dwelling-places of his assistants.

‘Let’s sit down and rest,’ suggested Morgana, ‘and talk about this. I do think the first thing to discuss is our position and what is to be done about it.’

‘What do you mean?’ asked Nicolette, as they squatted on a shady patch at the very edge of the hill whence all their world lay spread beneath them.

‘I mean that it is time we women were no longer subjected to such abominable tyranny. Here we are, pushed into their beastly rigid castes and divided off into breeders and non-breeders to serve the race. I don’t care about the race. But I care for experiment. When I was sixteen I wanted to experiment with everything, including my own body. No one tried to stop me, but of course I had to be immunized. Now I have exhausted that, and I should like to have a child. But they forestalled me. The most interesting experiment of all is denied me. And the same will happen to you.’

‘But I don’t want a child,’ answered Nicolette smilingly.

‘Not now. But you will. Sooner or later we all do. If you don’t sooner, they won’t let you later.’

‘Well, that’s got to be,’ asserted Arcous. ‘You can’t have it both ways, and you can sublimate your maternal cravings.’

‘For your benefit,’ retorted Morgana angrily. ‘Of course the arrangement suits your sex admirably.’

‘And the majority of your own,’ he replied provokingly. ‘You won’t get much encouragement if you begin trying that kind of reform.’

Morgana turned from him and appealed to Christopher.

‘Don’t you think,’ she said, ‘we should have an opportunity? Why not have it both ways?’

‘I absolutely agree with you,’ he said. ‘I think it’s disgraceful that intelligent people should be robbed of their free will in any way. But governments never did and never will make special laws for intelligent people.’

‘Then why not make our own?’ demanded Morgana. ‘We’re too amenable, too reasonable, altogether. We’re simply being flattened down.’

‘You see,’ Christopher told her, ‘public opinion has become so much a part of each individual’s own opinion that we are becoming totally absorbed in the herd, so finely welded to it that we cannot detach ourselves. Every one of our herd instincts has been comfortably satisfied — at the expense of our individual strivings. To stand alone has always been difficult; to make a gesture of defiance, painful. And for us it is almost impossible, because there’s no glamour left in it. All it would lead to would be treatment or a silent elimination. Where there’s no shouting there are no martyrs.’

‘Well, here’s an interesting situation,’ said Morgana bitterly. ‘Five intelligent and young people, all for various reasons dissatisfied with existing conditions, and yet not one of them prepared to have a fling at them.’

‘Not prepared is the only bit of your pessimism I agree with,’ replied Christopher. ‘But that’s not final.’

‘Well’ — suddenly Morgana’s eyes were brighter, for an idea had developed in her mind — ‘let’s all say what we want and how far we are prepared to go to get it. You begin, Bruin.’

‘Oh, why bother,’ he grumbled. ‘I’ve told you already.’

‘It’s the only reason why I bother with you, as you know,’ she retorted. ‘As for me, I want complete, complete freedom.’ She looked lovely as she threw out her hands towards the valley before her.

Arcous appreciated the picture she made, but could not, as usual, forbear to taunt her.

‘And you dare call yourself a scientist,’ he scoffed.

RADIUM AGE PROTO-SF: “Radium Age” is Josh Glenn’s name for the nascent sf genre’s c. 1900–1935 era, a period which saw the discovery of radioactivity, i.e., the revelation that matter itself is constantly in movement — a fitting metaphor for the first decades of the 20th century, during which old scientific, religious, political, and social certainties were shattered. More info here.

FICTION & POETRY PUBLISHED HERE AT HILOBROW: Original novels, song-cycles, operas, stories, poems, and comics; plus rediscovered Radium Age proto-sf novels, stories, and poems; and more. Click here.