OFF-TOPIC (66)

By:

November 14, 2024

Off-Topic brings you over-the-transom, on-tangent essays, dialogues and subjective scholarship on an occasional, impulsive basis. This time, for a new era of uncertainty, a centering talk with a writer I’d follow into heaven, hell, or their fictional, figurative equivalents…

Ram V can’t not write epics — or ever forget the human scale that defines them. His works for the franchised comics world situate the commonplace in the continuum of the cosmic, historic and supernatural, and his creations for indie comics center the divine on the everyday. Unforgettable runs on The Swamp Thing elevated that series to an existential ecological drama with a pantheon of personified elements battling for the equilibrium of nature, humanity and technology; on Catwoman expanded that series’ class-strata themes to a Les Mis-level saga of the dispossessed’s struggle for survival; and on Detective Comics deepened Batman’s mythology to a narrative symphony (actually titled “Gotham Nocturne”) of personal and literal demons contending for the always-borderline hero’s conflicted soul and the character of his city. Indelible visions of V’s own creation like The Many Deaths of Laila Starr and Rare Flavours (both from BOOM! Studios) cast divinities amidst the sprawl of humanity, to see what these beings of pure concept can learn from ordinary mortals’ ideas (in the first case, the goddess of death confronting the consequential ending experienced by humans, albeit time and again; in the second, a voracious human-eating demon of Hindu lore self-reinvented as a master chef and apprenticing an aspiring filmmaker to tell his story and explain their respective appetites and ambitions to the world, each other, and themselves).

The DC comics complete the kind of epic cycle Jack Kirby dreamed of seeing through with his Fourth World comics of the early 1970s, and the indie series address the same preoccupation with humanity and divinity coming face to face that anchored that and most of Kirby’s work — so it’s only providential that V should now be inheriting that cycle’s flagship series, The New Gods (with artist Evan Cagle), and characteristically surprising that there is a majestic quiet and human focus to this most big-picture of franchises.

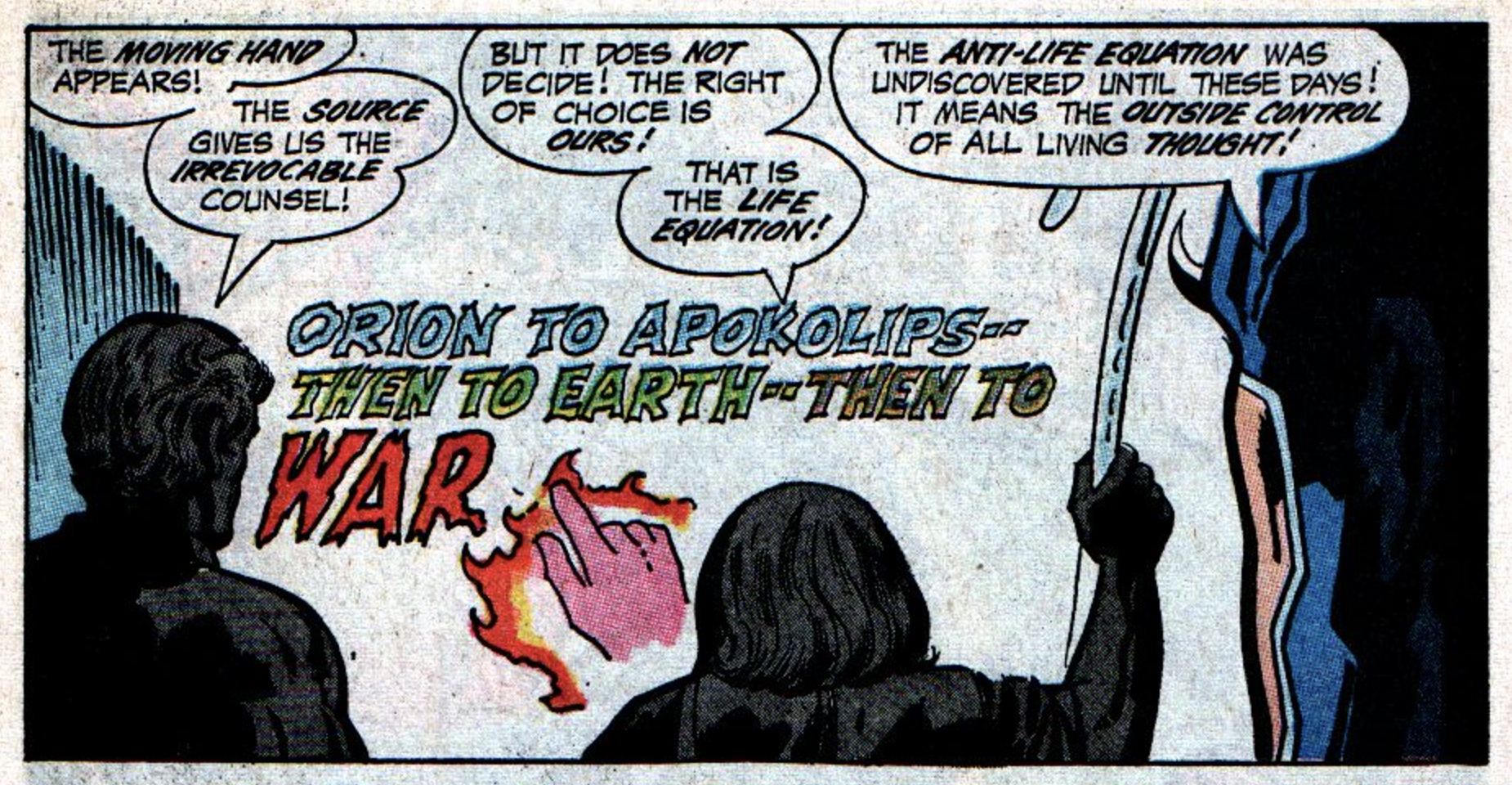

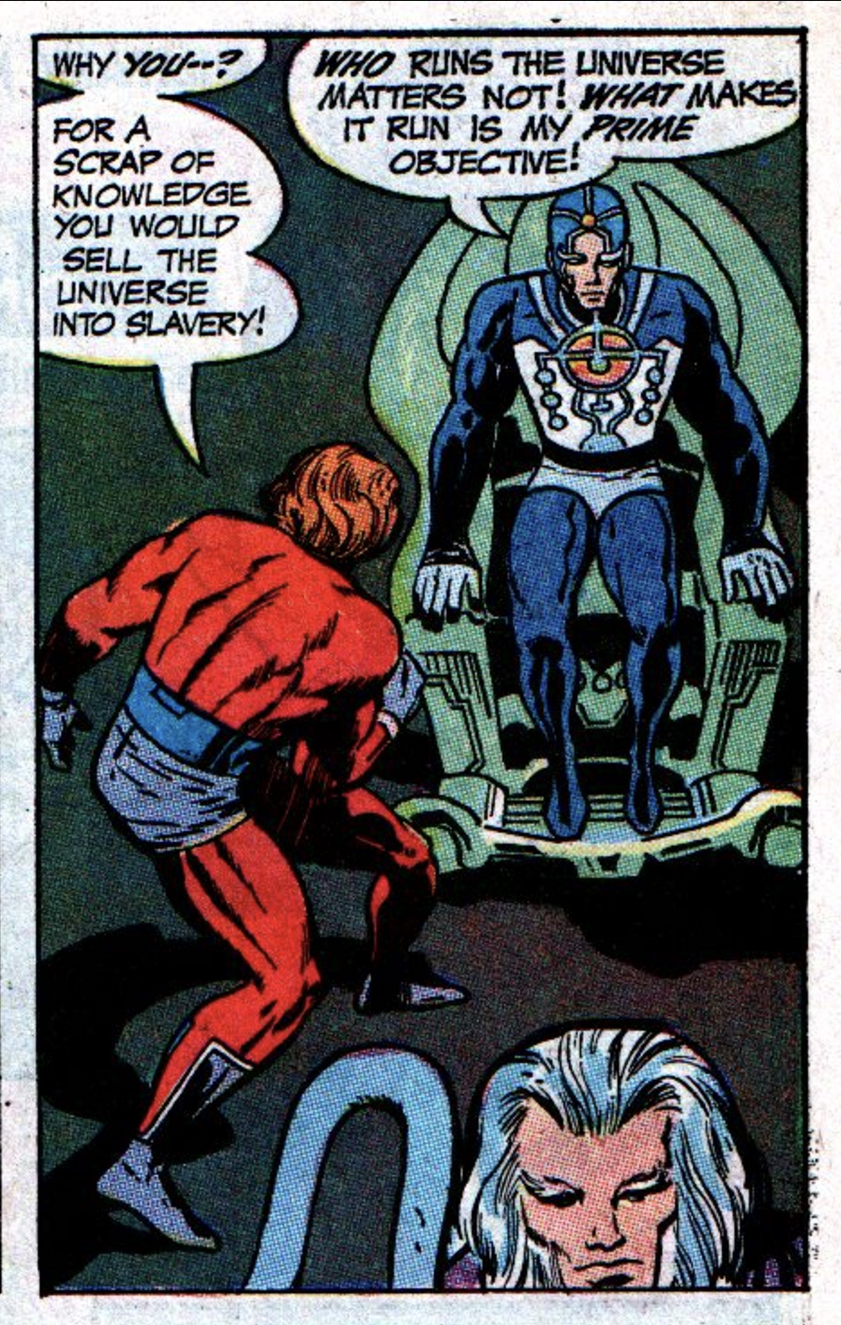

The main contours of Kirby’s original are increasingly well-known as their influence on generations of later pop-culture spreads (and anticipation of real-world tech manifests): Two warring worlds in a higher dimension, New Genesis and Apokolips, are created from a single planet that split in two from a cataclysmic final confrontation. Kirby was splicing ancient myths like the Norse/Teutonic twilight of the gods with a new metaphoric fable of nuclear war and the US/USSR conflict, and seeing forward to the next few decades’ fantasies and inventions; the anti-hero Orion, who fights for high-minded, supposedly utopian New Genesis, is actually the hellish Apokolips’ ruler Darkseid’s son (a la Luke Skywalker); the “New Gods” commune with a spiritual power called The Source (rhymes with…) via talismanic portable devices called Mother Boxes that look a lot like Mac towers or smartphones. Orion was swapped at birth with New Genesis’ ruler Izaya aka Highfather’s son, Scott Free, as mutual hostages to keep a fragile peace; when Scott escapes, to Earth, the war restarts and we mortals get swept up in it. In Kirby’s updated cosmology, Scott (aka Mister Miracle, Super-Escape Artist) becomes the god of refugees; Darkseid is the god of despots; an amoral agent who advises and arms both sides, Metron, was described by Kirby as the god of the atomic scientists; and so on.

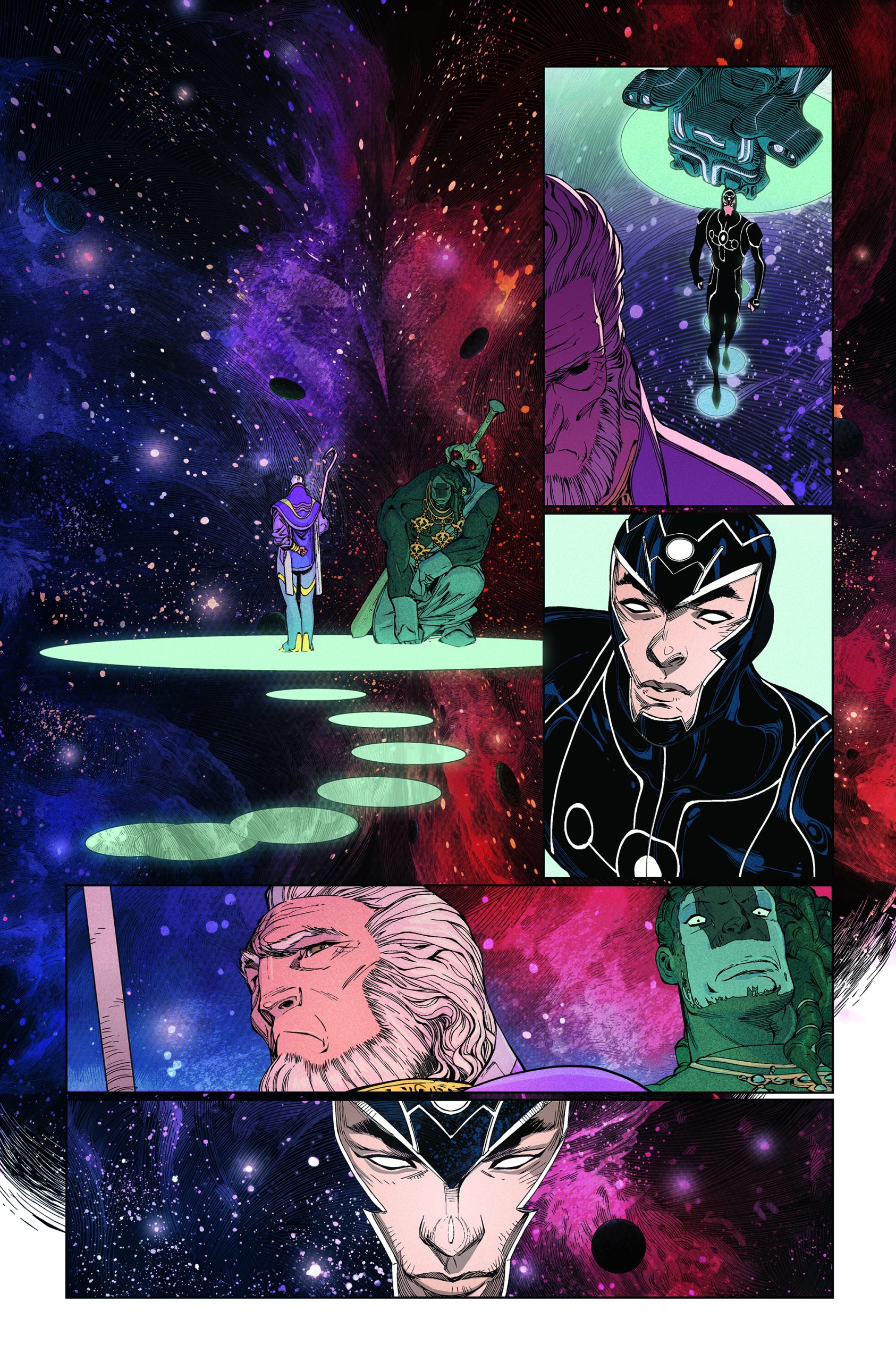

In DC’s current continuity, Darkseid has just “died” and been reconstituted as a whole parallel universe built around his dark persona and worldview (the Absolute line of comics); this leaves a vacuum on New Genesis and an uncertainty on Earth. Metron has received a cryptic message from the Source that New Genesis hierarchy take as a bad portent about an even new-er, young god being born on Earth and posing a threat that they don’t understand but want to prevent. The dutifully violent Orion and the habitually dissident and peaceful Scott are at odds about what to do about it. The weight of destiny, the burden of tradition, and the human stakes of sacrifice were always core themes of the Fourth World, and V’s sense of cosmic and personal consequence matched with Cagle’s humanist figure work and heady Gustave Doré/Alex Raymond visual poetics make them the most fitting heirs to this ongoing sci-fi testament. I spoke with V by zoom on 11/11/24 to receive the word on what’s to come, when the book debuts in December…

HILOBROW: Kirby’s graphics in the original were known for their spectacle yet Evan’s are marked by an elegance; and Kirby’s writing was known for its grand scale, while to me, your story feels like the most intimate in focus of any New Gods story that I’ve read. So I was wondering if perhaps the way to surpass the original might be to head into an uncharted opposite direction?

V: Kirby’s narrative was very much marked by his sort of off-the-page, jumping-out-at-you kind of spectacle. But I also feel like, you know, comics evolve and change with time, and so do narratives. So, I don’t think this is born out of necessarily a need to push away in the opposite direction, but it’s born out of a need to create something that feels like it is of this time here and now. And I think focusing on character, focusing on intimate moments while still having that sort of big spectacular, “Here’s New Genesis in all its glory” kind of moments, I think having that balance is great for the book. Because that’s the kind of stuff that I love doing, which is taking the big and then balancing it with the small and intimate stuff. Which, you know, in all fairness, I think Kirby’s characters have stood the test of time because they are so relatable and that you can invest into their struggles.

HILOBROW: Interesting you should mention it, because one thing that particularly fascinates me and I think surprisingly few successors to Kirby have dealt with is the dynamic between Scott and Orion. They have a unique bond, which of course, was a unique separation; you know, they were sent away from each of their warring parents to live with the other. And to explore what that must be like between them has always been a fascination for me — in the way that the New Gods personified certain modern traits that we wouldn’t necessarily have seen reflected in the classic gods, for me, I see Scott and Orion and I think of my own relationship with my siblings from my dad’s previous family — not the kind of thing you ever got in reading about, you know, the Greek gods — and I was wondering if you had a particular interest in showing that dynamic because for me, it really jumps off the page!

V: Yeah. And I think that’s what I mean by, I like my narratives to be driven by the grand spectacle as much as I like them to be driven by these very — I know it’s a little bit of an oxymoron, but, very human struggles, even where these gods are concerned. And it is a very human thing. And I think honestly, that’s what new readers will latch on to, is the fact that everyone’s got a relationship that they find both troubling and inspiring at the same time; everyone’s got a relationship where they really care for someone, but also realize that the two of them are so far apart and coming at the same thing from two opposite ends. And so how do you reconcile that? In everyday life, maybe over a cup of coffee and then some conversation, but when gods are concerned and the fate of the world hangs in the balance and two planets are at war with each other, you know, that kind of stuff takes on a completely different, very comicbook-y color. So yeah, very much something that I’m looking forward to getting into.

HILOBROW: People coming together over their differences is something that is of a compelling interest to Americans at the moment. And we just came through an election where many of the campaigners it seems were more concerned with beating some supposed statistics than with making a case. It’s like we’ve gone from prophets to mere “experts,” and in that light, in your book I can almost see Metron as having gone from being the god of amoral science to being the god of prescriptive polling. You know, he’s got this prophecy that he says you’ve got to follow… I’m coming at it this week from a very specific lens, so I’m wondering how you saw that characterization.

V: Science, statistics, they don’t account for feelings and emotions and morality. They are as they are. And I also find it very interesting that Metron has this sort of communion with the Source which no other god has access to quite in the way that he does. And so it seems to me a lost opportunity if Metron were not the kind of character to keep some of the prophecy to himself and only give out what he thought was statistically important for each side of the struggle to hear. And so to me, Metron is kind of born off of this Hindu mythology character in my mind. There’s a character in Hindu mythology called Narada, who is this sage, all-knowing and wise, but he seems to take extra delight in going over to gods and other important characters and sort of needling them just enough to get them to act one way or the other and then sitting back and watching the chaos play out. So yeah, I would be very reticent to say whether Metron is a good guy or a bad guy. I would like to say he’s both above and beneath all of these classifications.

HILOBROW: When you mentioned his unique form of communion with the Source, it didn’t escape my notice that, we’re used to seeing the reception of the message from the Source being a passive thing, like in the original New Gods #1 by Kirby, when Izaya takes Orion to see what’s going to be written on the wall. Whereas only Metron, it seems, is like forcibly extracting information from the Source, which was an interesting contrast.

V: I like to think that the Source’s communications are largely beyond comprehension even to most of the other gods. And so you would need kind of Metron’s abilities and powers to be able to actually discern long-term what the Source is trying to do. Whereas, when Izaya sees those burning letters on the wall, or has these visions from the Source, they’re largely sort of broken garbled shouting from the Source Wall trying to communicate with him. And so what Metron says and what the Source Wall shows might be motivated by entirely different things, which is great for a dramatist.

HILOBROW: Like a living Ouija board. Like, I love how he comes and starts to tell Izaya what to do and then he’s like, “I wonder what you’ll do?”

V: Yeah, but also, as a scientist, the greatest joy for a scientist is in dropping a catalyst into a reaction and go[ing] like, I wonder what will happen now. And I think we’re seeing that sort of playful curiosity play out from Metron because his interest is not in this one instance, his interest is in studying 10 years down the line what are these experiments going to lead to? And so, yeah, someone who’s playing 6-D chess while other people are just figuring out how to play 3-D chess, is interesting.

HILOBROW: Central to the ambiguity about Metron and “is he a good guy or a bad guy?” is the binary that doesn’t exist anymore, or at least it doesn’t exist at the moment in the DC Universe and in your story. Kirby conceived of the original Fourth World as a finite cycle, even if it might have gone for thousands of more pages. In this book there’s this palpable feeling of the characters having outlived the end of something. Almost a melancholy, as when Metron suggests to Izaya that he almost misses Darkseid. And the characters, particularly Highfather, are panicked about what their purpose is now. We know that the world never ends though “our” worlds sometimes do, and it’s poignant how many characters in your book are already so frightened about newness (ironic, given the name of the book) that they’re ready to see a child as a threat. Is part of the message that the ability to change is how we really survive — and maybe these guys are all missing it?

V: Yeah. And also I think when change happens on cycles that are far beyond our perception and things we don’t see as dangerous or alarming, maybe the gods do. What’s another child born into a world of billions? But for gods, if that child is prophesized to bring about great change… these are characters that have sought to establish some sort of status quo over lifetimes of entire planets and civilizations. And so for them, anything that threatens that is a source of great alarm. And I also find it very interesting in that the “New Gods” have been around for decades. So what’s so new about them? And so having to contend with not being the newest of the New Gods is also an interesting thing and an angle that we will start seeing as the future issues crack on, because there are some New Gods who are not quite excited by the prospect of not being the new god anymore. You know, almost this sense of like “Wait, I was supposed to be the next generation.” Am I being passed up now for some other kid who’s going to be important? So we’ll start seeing those things play out as the story goes on.

HILOBROW: It’s funny, Grant Morrison planned to [introduce] the “Fifth World” in Final Crisis in ways that I think were significantly suppressed… I mean, editorially, obviously that was not a popular idea but, you know, it never occurred to me that — I got the impression that Grant was seeing even this as a kind of natural evolution. It never would have occurred to me that yes, the existing “new gods” might have something to say about that and you know, be threatened.

V: Yeah. And I like that idea. I mean, this is largely also me drawing on Hindu mythology more than the Greco-Roman stuff. In my experience of both mythologies I find Hindu mythology to be much more allowing of gods to not be these sort of iconic, emblematic, good guys/bad guys, “we only act in just ways” kind of characters. So does Greco-Roman mythology to an extent, but the complexity of a god going “Wait, I don’t get to be a god anymore? I’m not relevant anymore?”— it’s such a nuanced thing. I’ve seen stories like that from Hindu mythology. So again, I’m pulling from there in terms of gods being jealous of somebody else achieving or being the new shiny thing if you will.

HILOBROW: I was fascinated by the fact that, on the first page we meet a god older than any of the ones we’ve seen, and then on the last page we meet the Newest God. And I was curious, what is your thinking in terms of how to draw new things into the Fourth World tapestry that seem to ring true with what came before but also will be fitting to the new fabric? Even though Kirby had this sprawling canvas and in every issue he was throwing in new characters and settings, relatively few have been added ever since in other versions. But it looks like you’re definitely diving into that.

V: Yeah, I think your reading is absolutely right. I mean, there have been new additions in terms of new characters added, but no one’s ever sought to add something outside of the bounds of what Kirby already set up. …I say no one but with the caveat that, I think Morrison did the most significant sort of expanding of Kirby’s ideas. Certainly in stuff like Seven Soldiers, Final Crisis, you can see Morrison kind of pulling from outside and adding and making the circle of Kirby’s Fourth World bigger. I like that because as somebody else, when I was talking about this with them, said to me, Morrison’s work seemed to see the DCU as this sort of singular-continuum mythology that started all the way from before the Old Gods, and continued down to the first superhero, and then all the other superheroes that came from there and then possibly towards the Fifth World. And I like looking at both the DCU and the Fourth World in that sort of continuum, [that] they’re all connected to each other and they’re all part of a grander bigger mythology. And then once you start looking at it like that, you can absolutely add one thing at one end and have it have ramifications in completely unexpected places. So a new superhero being born on Earth should be a matter of no concern for gods. But the moment you say, “Actually this might change everything for the Fourth World,” then suddenly everyone is involved. And I think we’ll see a lot more things like that. Part of my pitch to DC when we started on this was that, why are these two things so sort of cloistered in their own worlds, the Fourth World being so distinct from the DCU? Everything should matter to everyone involved. And so I’d like this story to really be that sort of grand unification, of the Fourth World and the DCU really having consequences for each other. So that’s one part of the motivation for doing it.

And then the other part of the motivation obviously is I think cosmic stories and space stories and these kinds of grand sci-fi operas have become too much about conflict and war. It seems to me that we are no longer interested in discovering new ideas, only in trying to decide who owns the ideas: is it the Empire or is it the Rebellion, is it Apokolips or New Genesis? To me, part of the joy of reading Kirby was that every page you were discovering something new. And so I very much want that narrative chunk to be here in this New Gods run where literally you’re discovering characters from the edge of space that even the gods have not seen before, and enemies that they didn’t know existed, and maybe even creating, or placing a force in active opposition to the Source. Because we forget, even though New Genesis and Apokolips are opposed to each other, they’re both fundamentally linked to the Source. And the Source only existed as a secondary creation; before the Source there was primal darkness. And so what does the darkness have to say about all of these creatures that have populated what used to be its domain? And we’ll start seeing the ramifications of that as well.

HILOBROW: “Cosmic” is a word that gets misused… abused to just mean space opera — which there’s nothing wrong with, but in my mind I kind of make a division between “hard cosmic” and “spiritual cosmic” as you were saying… I might almost say, like, “Carl Sagan cosmic” and “Timothy Leary cosmic”; you know, one that’s about hardware and the other that’s about more the inner journey and the revelation.

V: Actually that’s the part I love, that there’s actually ways to reconcile both the hard and the inner cosmic, right? Like, two objects colliding in space should also have some meaning for what happens when two philosophies collide inside your, inside your interior. And the beauty of cosmic stories lies in being able to reflect the interior experience through these sort of grand events that are happening outside. And again, I think [in] Hindu philosophy and mythology there is a huge component of that, which is why historically India has been the destination of “the hippies” who want to “find themselves.” So I think pulling on some of those threads is also going to be very interesting for the story.

HILOBROW: I’m sure. And as much as people focus on the spectacle of Kirby’s visuals, I’m always fascinated about how writers approach the Fourth World’s ornately crafted language. How that’s expressed ties in with some of the scale and scope of the concepts that you’re talking about. I loved how there was almost this feeling of “scientific scripture” to Himon’s intro in this issue; and, we see the contrast between the kind of weighty, dramatic speech of Orion and the colloquial speech of Scott…

V: Which is indicative of where they are from and where they’re coming from, if you will.

HILOBROW: Absolutely. And I guess that kind of answers my question about what sounded right to you about how these characters would speak… and also, what is new that you bring to it? Because there were generations of writers who thought that they could “fix” Kirby and make [his dialogue] more “realistic.” Even though as Grant has said [quoting Jung], “the Archetypes speak in the language of bombast.” So, you know, it should be more…

V: 100%. When we started off, you know, one of the big questions was like, “Why is this gonna feel new”; New Gods has existed for such a long time. And I said, “These are gods and no one’s ever seemed to want to convey this idea that we are not watching gods punch each other or fly through space; we are watching stories that will be told 100 years from now as sort of [current] mythologies unfolding,” right? So when we set out with this book, we set out to create something that would feel like you were collecting pieces of sort of neo-mythic scripture. And so, the Metron prophecy page that you see, or the extracts from Himon’s Prometheus Codex that we will see throughout the run, these are meant to feel sort of scripture-like. So I’m glad that that comes through. And then obviously on the other end, it still has to be a relatable story for someone who’s drinking their cup of coffee and reading a comic. And it shouldn’t feel like they’re reading the Kabbalah or the Bible, if you will, it should feel like they’re reading a comic book. And I think that’s where elements of Scott Free continuing to communicate like he is from Earth and not a God or, as we will see in future issues, the villain for at least this chunk of the story is going to be someone who’s very much earthbound and perhaps aspires to godhood in some way. And so those conversations will certainly be had in the language of earthbound people, and so should feel and read as if they came from there.

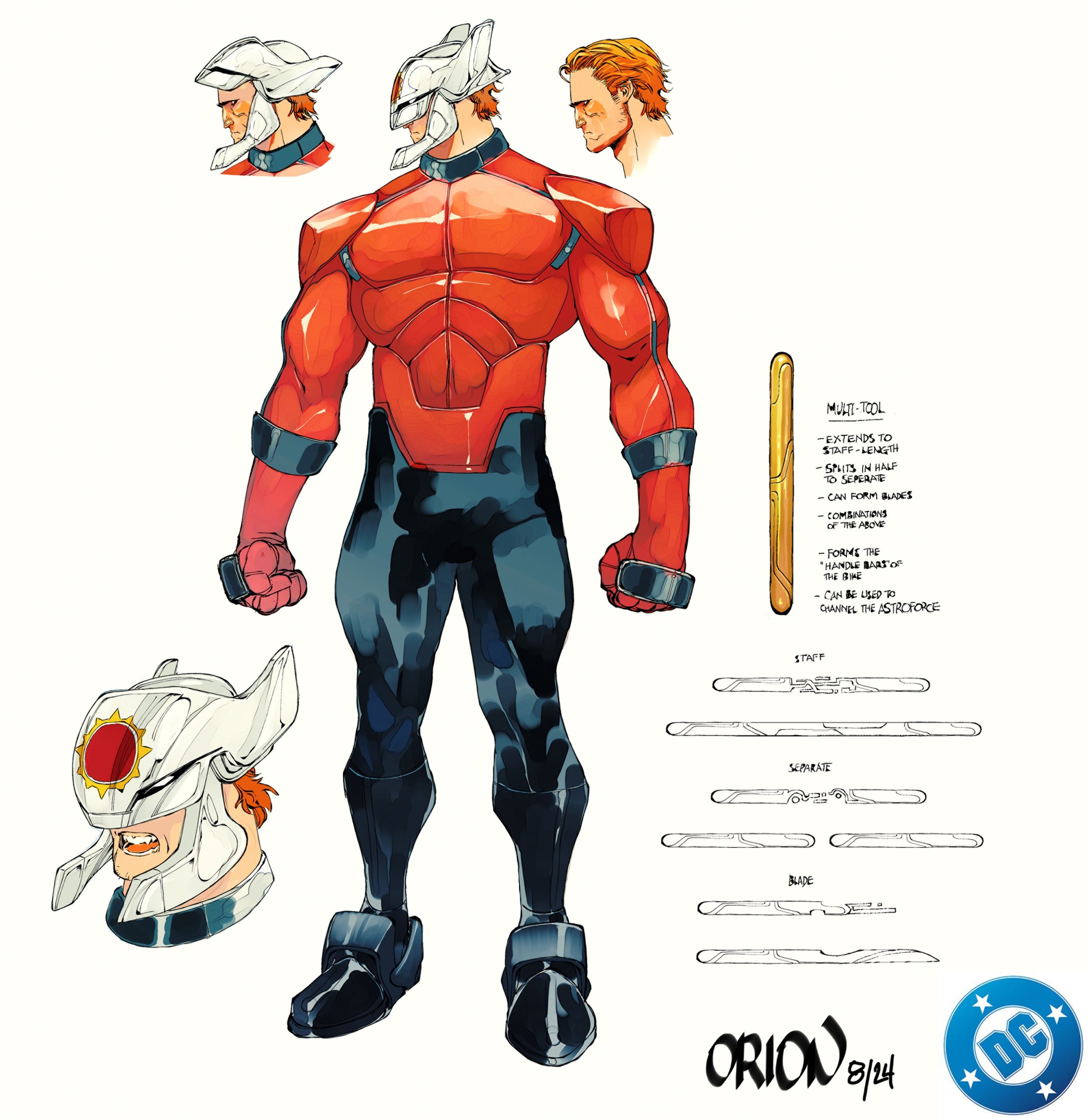

HILOBROW: Hand-in-hand with this — this is mostly a question for Evan, but I’m sure that it was a matter of very close consultation between you — we have this morphability of the New Gods, they can mean something different in different eras; certainly Darkseid kind of went from being a Nixon metaphor to a Reagan metaphor between the ’70s series and the Hunger Dogs graphic novel. But part of that is also their [evolving] look, and I’m fascinated about what kind of, either what directives you might have suggested to Evan or what he brought to the table in terms of how these characters would manifest in a new visual aspect for these times. We have almost a mech look for Orion, which is completely new to that character, and we have Highfather in this regalia of mourning which is a little different for him, and Scott has this kind of character-actor look that really accentuates his earthboundness… what decisions, what considerations went into how these characters would visually come across this time?

V: I’m not a huge fan of nostalgia when it comes to aesthetics and design and storytelling. When the original Fourth World stuff was coming out, Kirby’s designs were meant to be something that indicated things that were from out of this world, you know, “Who dresses like that,” “Who has guns that look like that” or “What spaceship is like a brick floating through space,” you know. But between that era and now, our understanding of space, and space travel and exploration and technology has changed in interesting ways, to where Kirby’s ornateness was an indication of his inexplicable sci-fi, whereas we now understand sci-fi to be minimalist in design, or effortless in a lot of ways. So I think those things should reflect on this comic, which is why even the Mother Boxes, which used to be just these sort of cubes that were carried around — as a reader coming to it now I’d go like, “well, what kind of backward civilization carries around entire cubes to communicate with each other when I have a sleek iPhone that I can just touch-screen on and talk to someone.” And so now these Mother Boxes are just part of their armor and it forms itself on their hands when they talk to each other. We’re also doing things with AI, what if there was an AI god that was living inside all of these Mother Boxes who we had never seen before. So there are new ideas that are reflected both in the narrative and the design. And so I think the design is largely fronted by that, but also, you know, comic influences have changed over time. I think Evan is a product of American comics, European sci-fi and Japanese manga aesthetics. And so that obviously reflects in his work. So the mech design, the sleekness of it all, the slight exaggeration on the characters, come from all of these influences rather than trying to sort of push away from one thing or the other.

HILOBROW: It’s kind of interesting to think that Kirby was trying to anticipate the future, whereas at this point it’s almost like you’re checking it against the present; you know, like how you say, if a Mother Box looks like an iPhone, what’s going to be impressive or futuristic about that?

V: Yeah. And I think that is reflective of the eras in which these things were written, right? Kirby’s writing came at a time that preceded the sort of telecommunications shift, paradigm shift in terms of what kind of technologies we were gonna be looking at; people then thought we were gonna get, you know, floating cars and teleportation and backpacks. And actually all we ended up with was touchscreens and social media. So I think there’s also a sort of recalibration of expectations in terms of where the futures have ended up, and [that] may be also a thing to address in terms of what this run on New Gods will do. So to me, the thing I found the most joy in was in this crazy sci-fi world [of Kirby’s] there was also the Newsboy Legion that were still selling newspapers; like who has newspapers anymore. I think things like that are interesting both to question and to reconcile within the narrative.

HILOBROW: You’re talking about the way that these things can morph and take the impression of the times that the stories are being told in. And that of course was Kirby’s mandate to begin with because he was like, well, you know, now we need a scientist god, now we need a dictator god, etc. But at the same time, the characters themselves, they have natures that they can’t necessarily ever break out of. You deal with this a lot in Issue 1 already; Highfather is kind of succumbing to his patriarchal role, Orion tries to work a way around his hunter nature, and he comes to Scott to say, actually work with your nature, your nature is to find escape routes and save people. What does this say about… do we readers, do we humans have a power to change our story that surpasses that of gods? Or, might we see the gods find their way to that themselves?

V: I think that’s where the drama lies, right? I think human beings fundamentally find beauty in things that vast outstrip their own lifetimes, like 500-year-old redwoods or a butterfly that lives and dies in a day. Both of those things are fundamentally beautiful to us. This is just a theory that I have, that the closer things get to our own lifetime, the less we appreciate them because [in other lifeforms] we see change reflected so dramatically or the lack of it reflected so dramatically. A redwood that’s 500 years old has been that way long past our lifetimes. Whereas a butterfly that lives and dies in a day will experience life so dramatically compared to us. And so we find both of these things beautiful.

So I think really the beauty of a New Gods narrative is in sort of contending with this idea that Orion perhaps sees himself as someone who cannot change, who can never change because he is the redwood, but Scott Free desires to be the butterfly, desires to have the sort of human mortality and therefore the morality that comes with that. And so those two ideas collide, and this is something that has been a preoccupation of mine outside of New Gods. If you’ve managed to read The Many Deaths of Laila Starr, essentially it’s a similar conversation that’s being had there. I love this idea that gods have something to learn from human beings as well, in that change is not an absolute or an objective thing. It is relative, much as time is relative and therefore all change increases or decreases in dramatic content depending on whether you live for 1,000 years or you live and die in a day. But you’re gods, you’re intelligent creatures, maybe you can learn to see the world as something in which the smallest change can be dramatic for somebody else that you may run across.

Images: (top) Cover by Pete Woods; (next two) interior art, New Gods #1, 2024 (unlettered) by Evan Cagle; (next two) interior art, New Gods #1, 1971 by Jack Kirby; (next three) interior art, New Gods #1, 2024 (unlettered) by Evan Cagle; character design, Evan Cagle; interior art, The Many Deaths of Laila Starr, words Ram V, art Filipe Andrade

MORE POSTS by ADAM McGOVERN: OFF-TOPIC (2019–2024 monthly) | textshow (2018 quarterly) | PANEL ZERO (comics-related Q&As, 2018 monthly) | THIS: (2016–2017 weekly) | PEOPLE YOU MEET IN HELL, a 5-part series about characters in McGovern’s and Paolo Leandri’s comic Nightworld | Two IDORU JONES comics by McGovern and Paolo Leandri | BOWIEOLOGY: Celebrating 50 years of Bowie | ODD ABSURDUM: How Felix invented the 21st century self | KOJAK YOUR ENTHUSIASM: FAWLTY TOWERS | KICK YOUR ENTHUSIASM: JACKIE McGEE | NERD YOUR ENTHUSIASM: JOAN SEMMEL | SWERVE YOUR ENTHUSIASM: INTRO and THE LEON SUITES | FIVE-O YOUR ENTHUSIASM: JULIA | FERB YOUR ENTHUSIASM: KIMBA THE WHITE LION | CARBONA YOUR ENTHUSIASM: WASHINGTON BULLETS | KLAATU YOU: SILENT RUNNING | CONVOY YOUR ENTHUSIASM: QUINTET | TUBE YOUR ENTHUSIASM: HIGHWAY PATROL | #SQUADGOALS: KAMANDI’S FAMILY | QUIRK YOUR ENTHUSIASM: LUCKY NUMBER | CROM YOUR ENTHUSIASM: JIREL OF JOIRY | KERN YOUR ENTHUSIASM: Data 70 | HERC YOUR ENTHUSIASM: “Freedom” | KIRK YOUR ENTHUSIASM: Captain Camelot | KIRB YOUR ENTHUSIASM: Full Fathom Five | A 5-part series on Jack Kirby’s Fourth World mythos | Reviews of Annie Nocenti’s comics Katana, Catwoman, Klarion, and Green Arrow | The curated series FANCHILD | To see all of Adam’s posts, including HiLo Hero items on Lilli Carré, Judy Garland, Wally Wood, and others: CLICK HERE