RADIUM AGE ART (1930)

By:

November 6, 2024

A series of notes regarding proto sf-adjacent artwork created during the sf genre’s emergent Radium Age (1900–1935). Very much a work-in-progress. Curation and categorization by Josh Glenn, whose notes are rough-and-ready — and in some cases, no doubt, improperly attributed. Also see these series: RADIUM AGE TIMELINE and RADIUM AGE POETRY.

RADIUM AGE ART: 1900 | 1901 | 1902 | 1903 | 1904 | 1905 | 1906 | 1907 | 1908 | 1909 | 1910 | 1911 | 1912 | 1913 | 1914 | 1915 | 1916 | 1917 | 1918 | 1919 | 1920 | 1921 | 1922 | 1923 | 1924 | 1925 | 1926 | 1927 | 1928 | 1929 | 1930 | 1931 | 1932 | 1933 | 1934 | 1935 | THEMATIC INDEX.

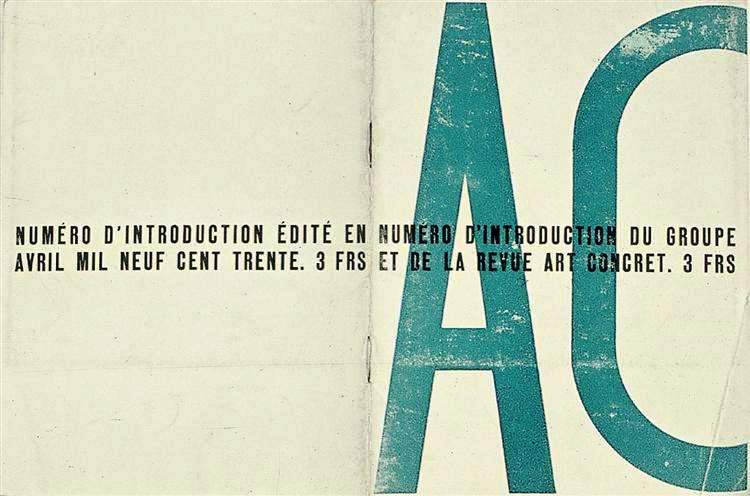

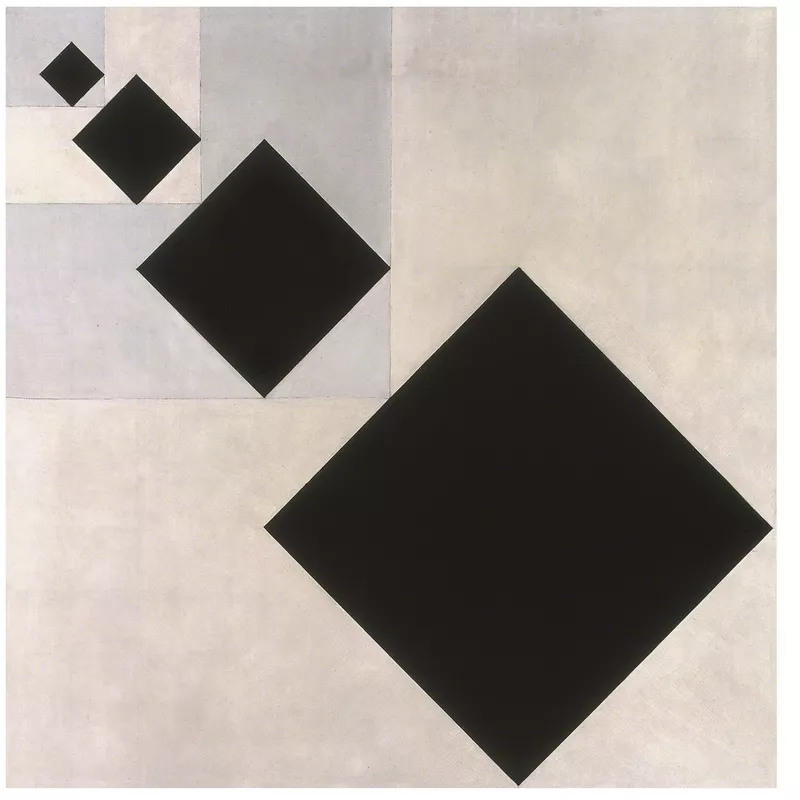

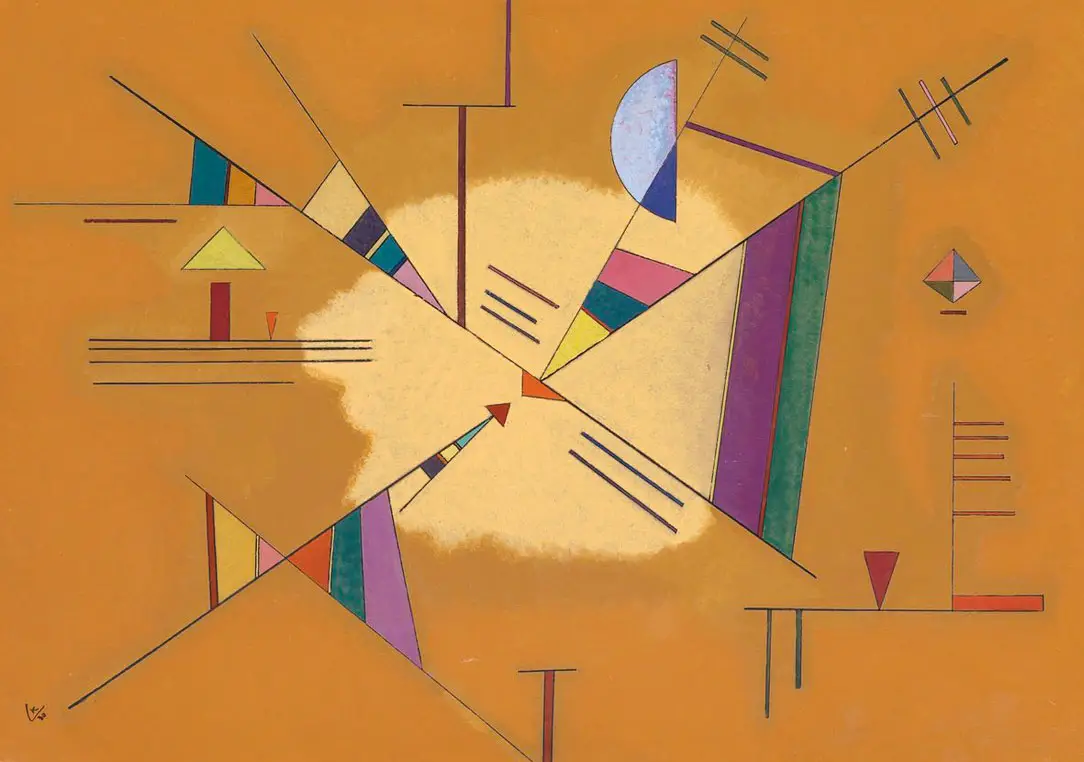

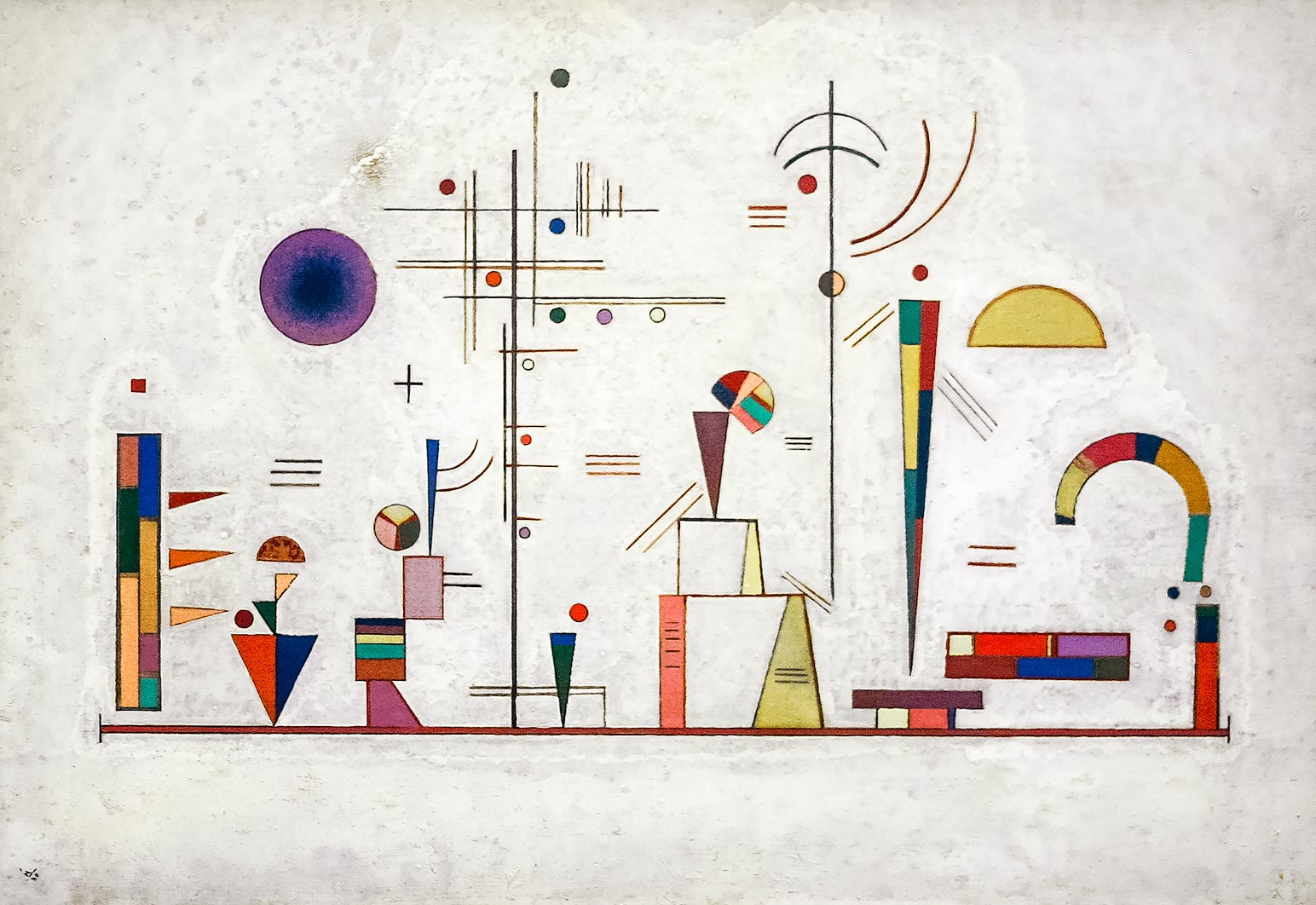

Theo van Doesburg produces a “Manifesto of Concrete Art.”

Art Concret was a single-issue French-language art magazine published in Paris in 1930. It was the vehicle for a group of abstract artists who wished to differentiate themselves from others gathered around the magazine Cercle et Carré. Eventually most in both groups fused in the wider association of non-figurative artists, Abstraction-Création. Articles in Art Concret championed strictly geometrical art, free of personal interpretation and based on mathematics. It also ridiculed the sloppy and imprecise vocabulary of contemporary art criticism.

The group manifesto, followed by the surnames of the five artists involved, appeared on page 1. The key points: “A work of art must be entirely conceived and shaped by the mind before its execution. It should receive nothing from nature’s formal properties nor from sensuality nor sentimentality. We want to exclude lyricism, dramaticism, symbolism, etc… The painting should be constructed entirely from purely plastic elements, that is to say planes and colors.”

Elsewhere in the journal, we read that “As painters, we think and measure,” i.e., avoiding interpretation and subjectivity. Jean Hélion’s “The Problems of Concrete Art: Art and Mathematics” writes: “If art is universal, it escapes both personality and era. It belongs to the domain of constant certainties and is under the control of logic. The search for constants through logic is the shared aim of mathematics. Mathematics concretise constant certainties via formulae; painting does it via colours. So mathematics and painting are in essential relationship.”

Debye uses x-rays to investigate molecular structure; Eddington attempts to unify general relativity and the quantum theory. Pluto discovered.

Also see: RADIUM AGE: 1930.

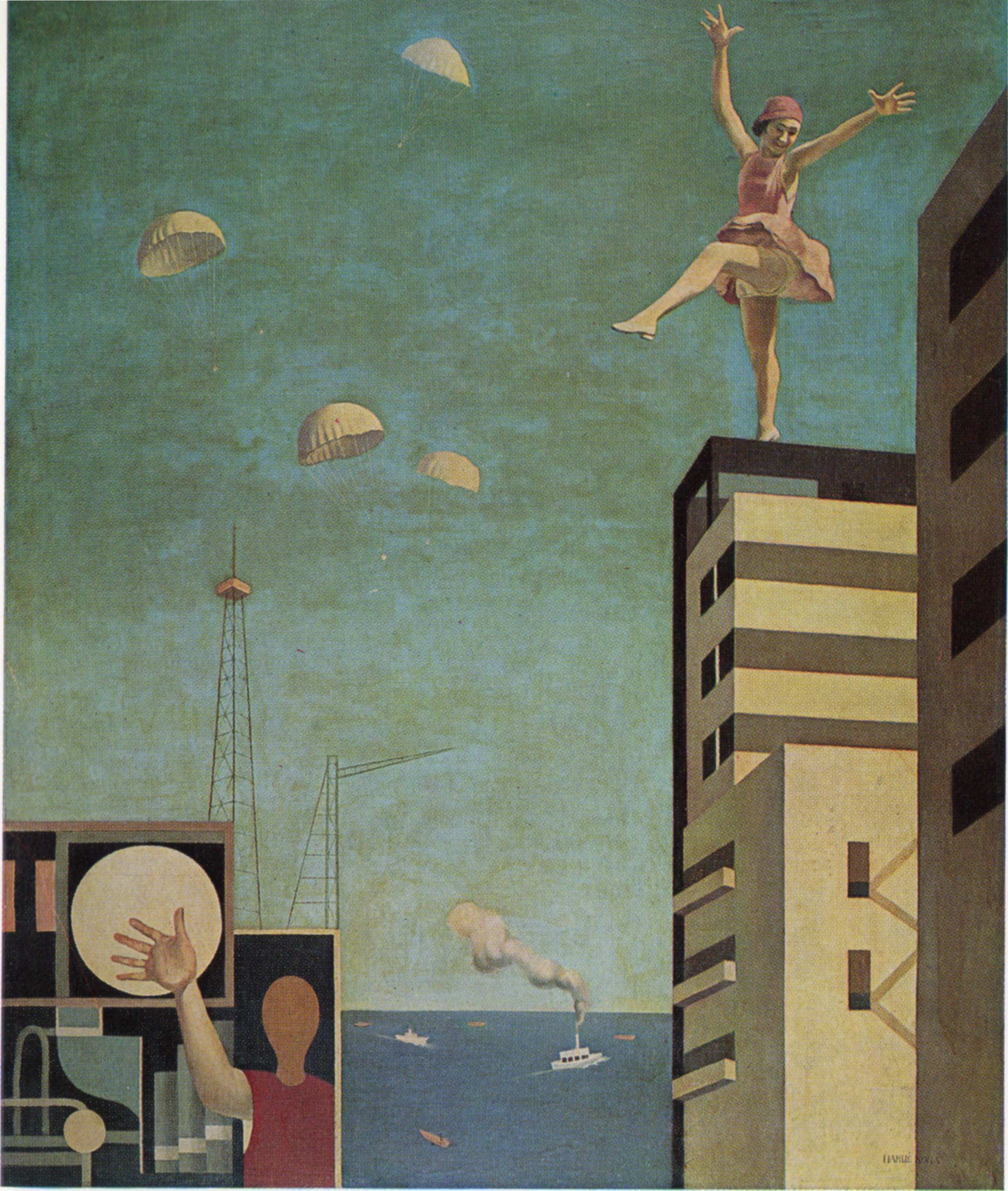

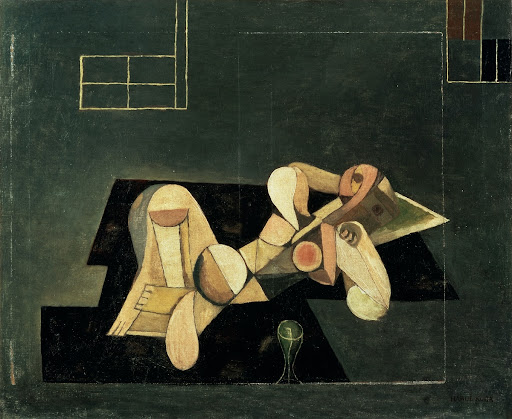

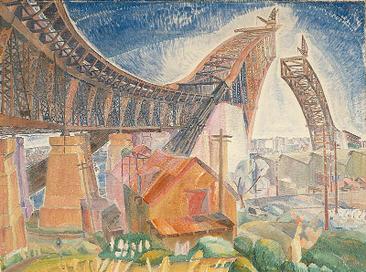

“This mildly surrealistic painting ironically posits the modernist language of industrial utopianism against the language of a socially committed art,” we read in The Thirties: Politics and Culture in a Time of Broken Dreams (1987), ed. Heinz Ickstadt. “The worker in the foreground has left the factory to either display, as trophy of victory, the paraphernalia of the robber barons, or his liberation from the iron-clad that they had forced on him.”

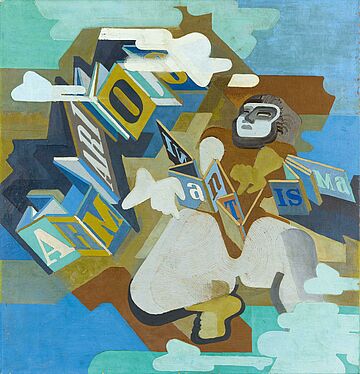

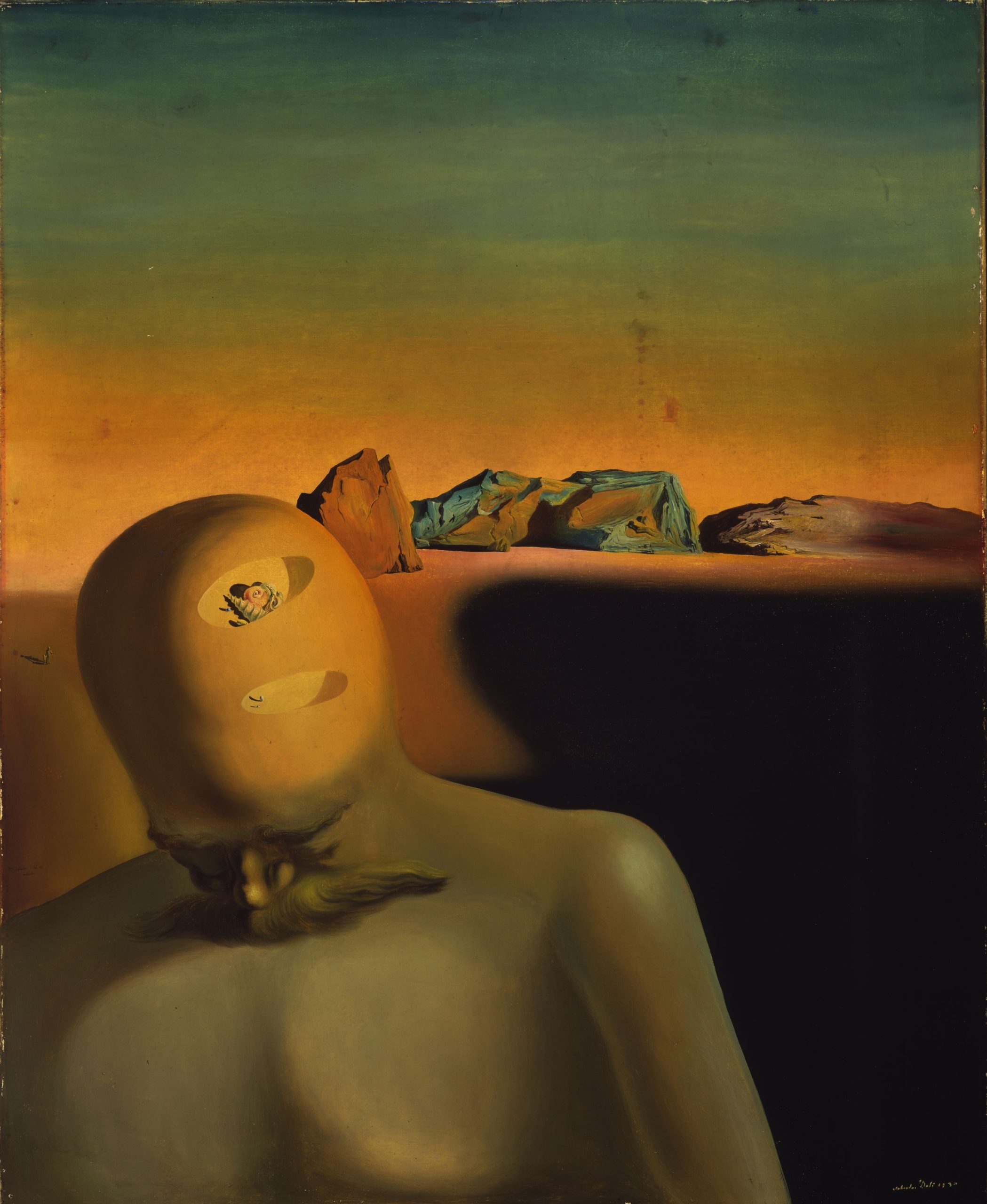

This painting rates a mention in Ballard’s “The Atrocity Exhibition” (1970):

Dr Nathan studied the walls of the empty room. The mandalas, scored in the white plaster with a nail file, radiated like suns towards the window. He peered at the objects on the tray offered to him by the nurse. ‘So, these are the treasures he has left us — an entry from Oswald’s Historic Diary, a much-thumbed reproduction of Magritte’s “Annunciation” and the mass numbers of the first twelve radioactive nuclides. What are we supposed to do with them?’ Nurse Nagamatzu gazed at him with cool eyes. ‘Permutate them, doctor?’ Dr Nathan lit a cigarette, ignoring the explicit insolence.

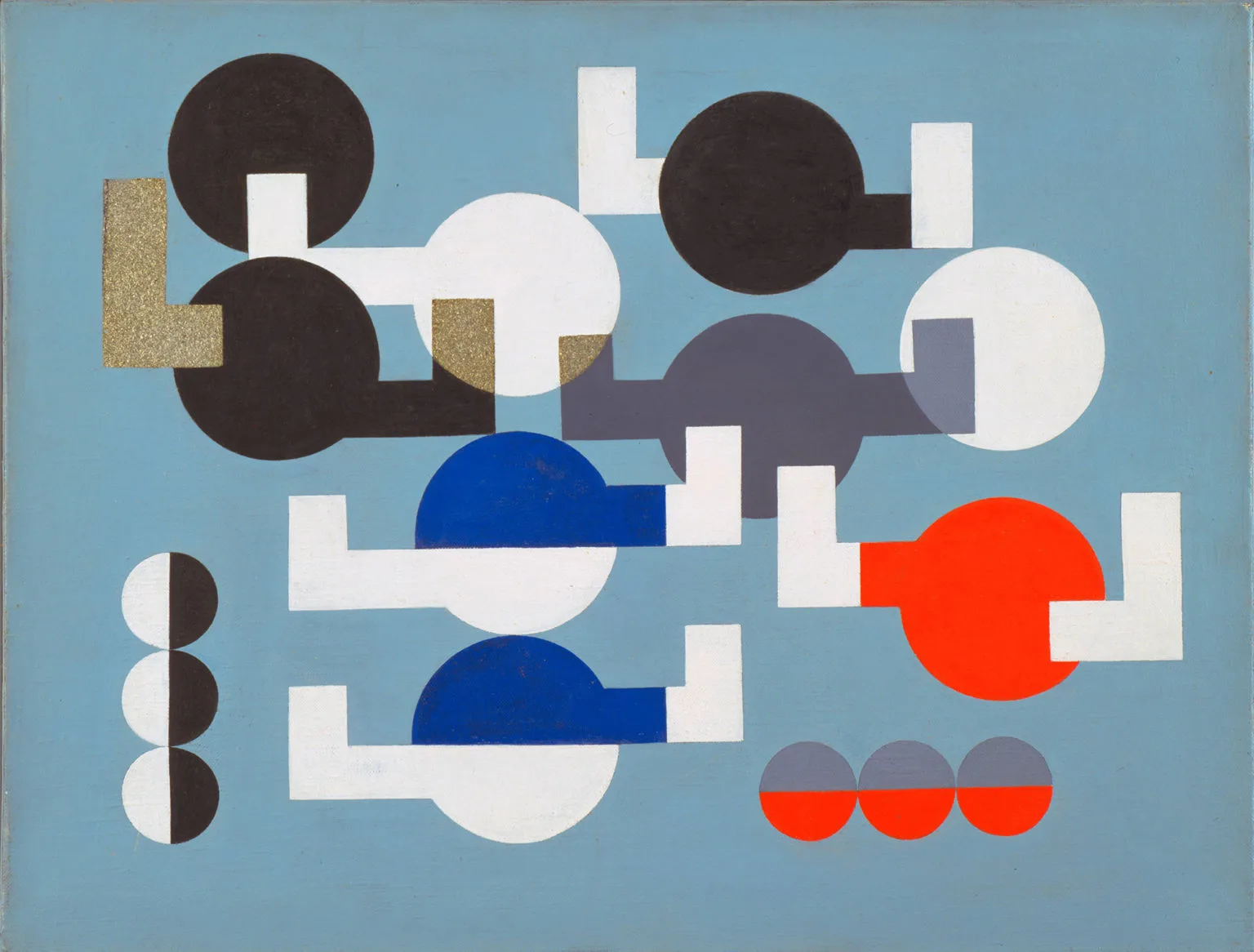

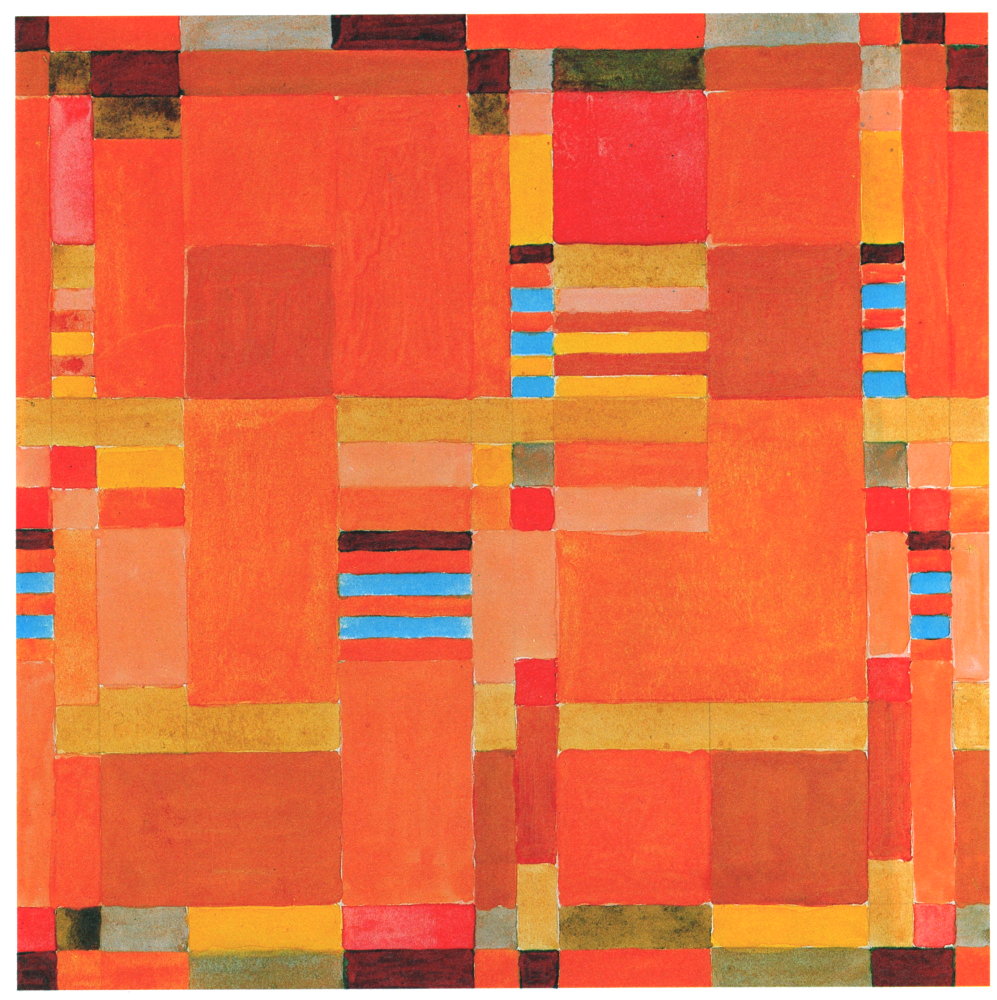

The principles of textile work—pattern, senses of proportion, the rationality of line—became the basis of Sophie Taeuber-Arp’s practice. Unlike her contemporaries Piet Mondrian and Wassily Kandinsky (whom she later counted as a friend), whose practices were guided by utopian values and spiritual concerns, Taeuber-Arp was simply interested by the interplay of geometry and color, and its potential to beautify everyday life.

A print of Feininger’s “The Market Church at Halle” (1930) was prominently featured in the first three seasons of the iconic television show Bewitched hanging over the desk in Darren Stephens’ office.

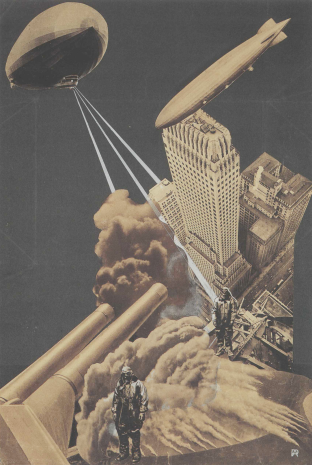

From the website The Charnel House: “Aleksandr Rodchenko’s grim sci-fi vision of the War of the Future (1930) illustrates the extent to which the terror of chemical warfare and advanced implements of destruction haunted the Soviet and European imagination of conflict following World War I and the Russian Civil War. Death-rays and dirigibles. Howitzers and skyscrapers. Chiaroscuro gas-masks.”

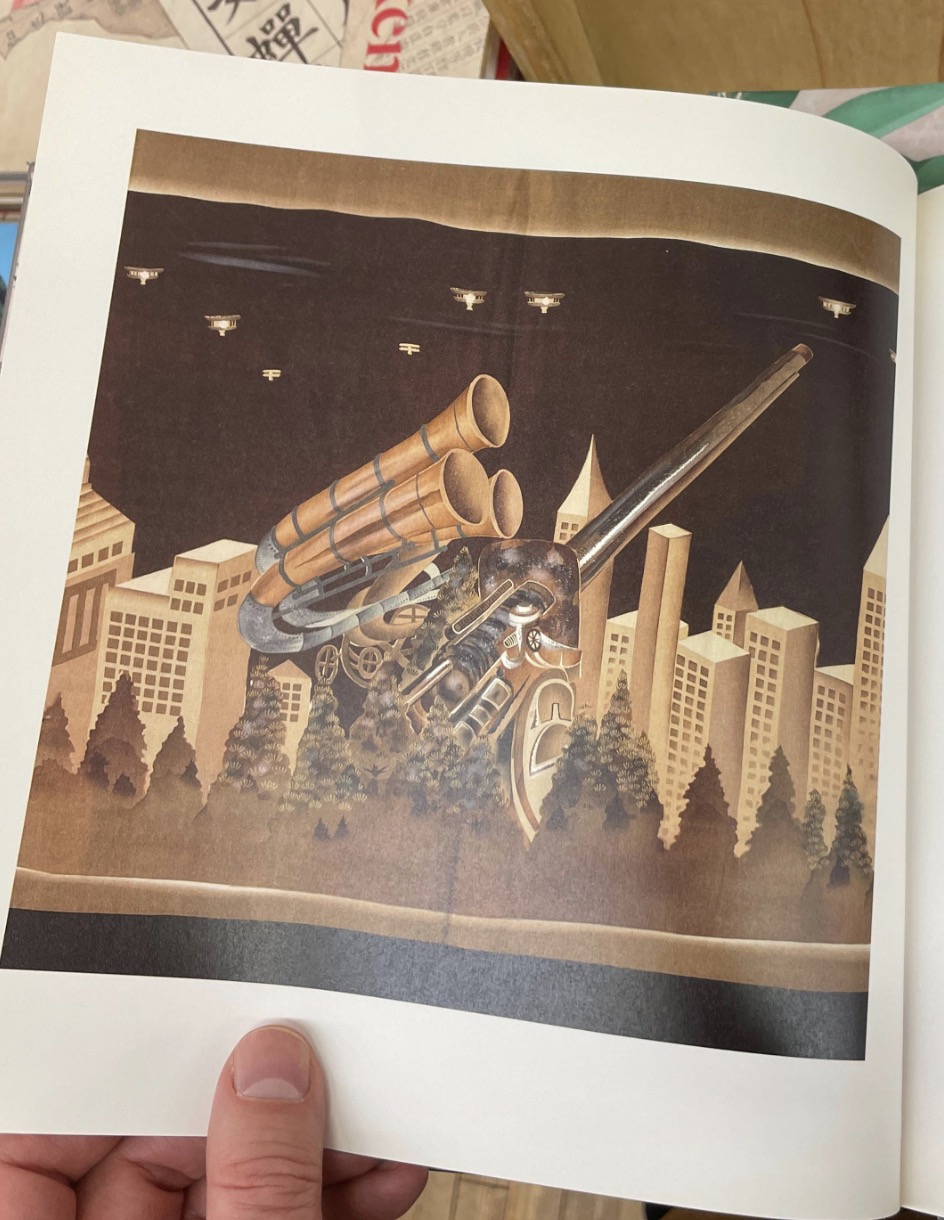

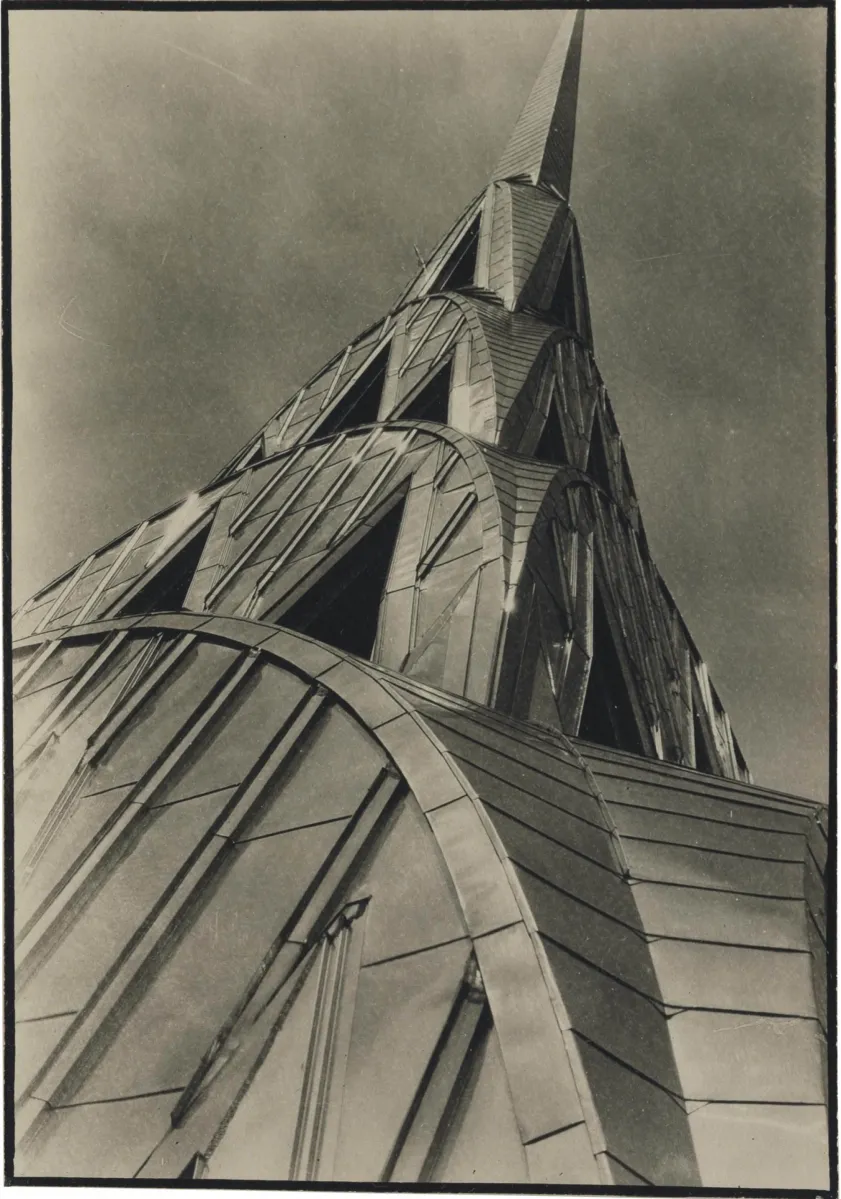

In this unusual haura, the designer positioned an acoustic locator (a device that detected aircraft by picking up engine noise) against a dramatic modern city skyline. The instrument is presented more as a piece of sculpture than an instrument of war, an impression underscored by its colloquial name, “Japanese war tuba.” From Jacqueline Marx Atkins’ The Brittle Decade: Visualizing Japan in the 1930s.

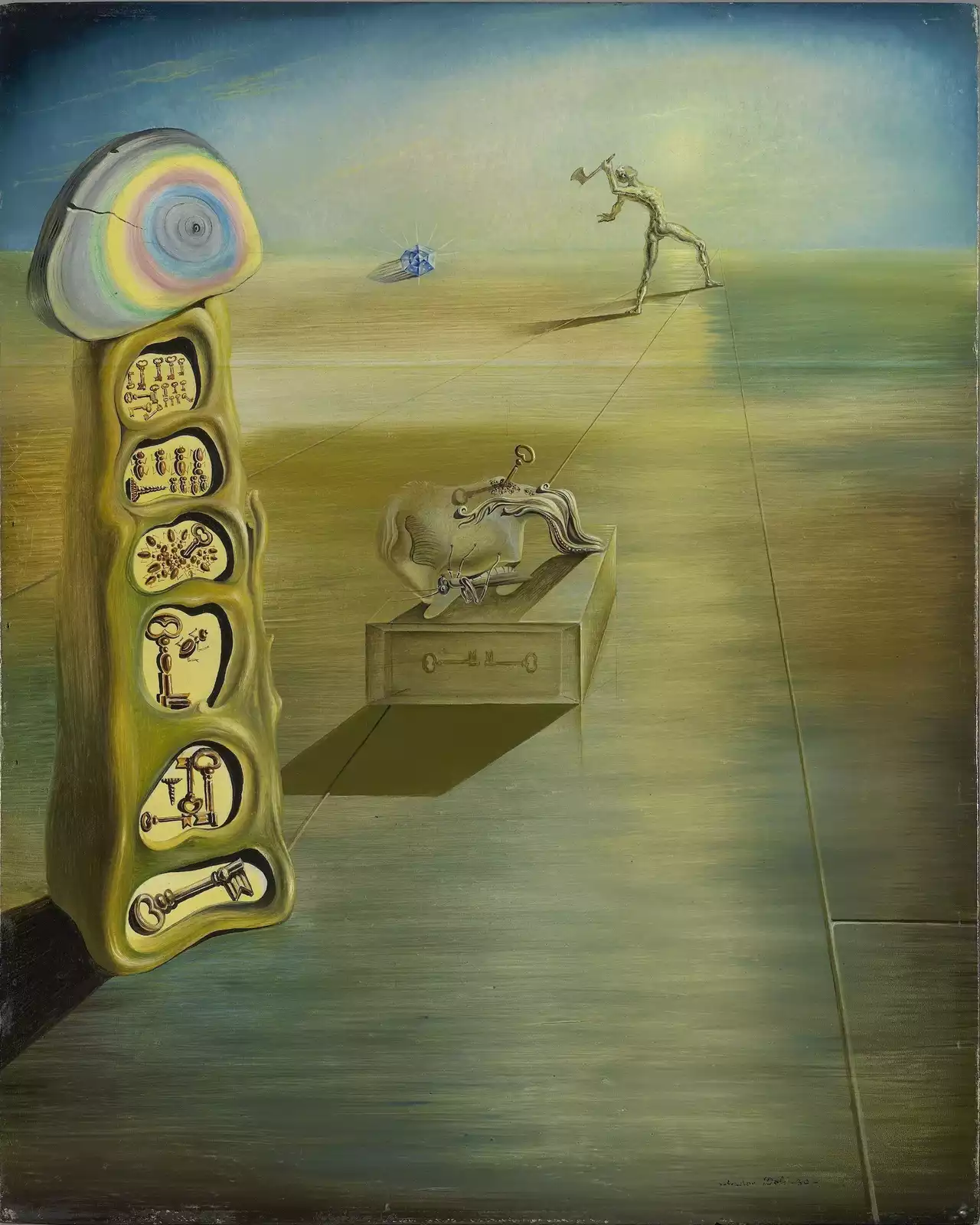

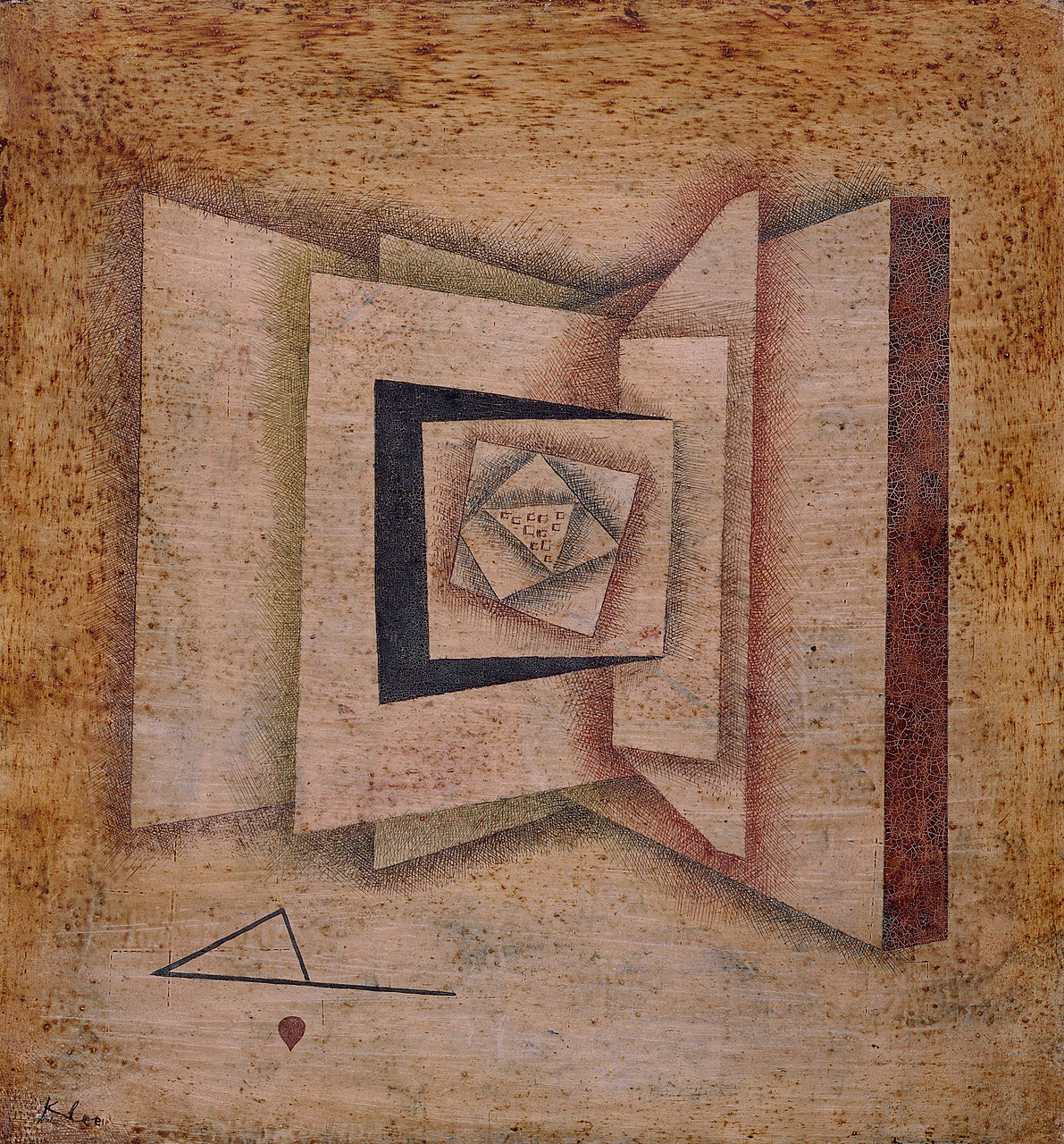

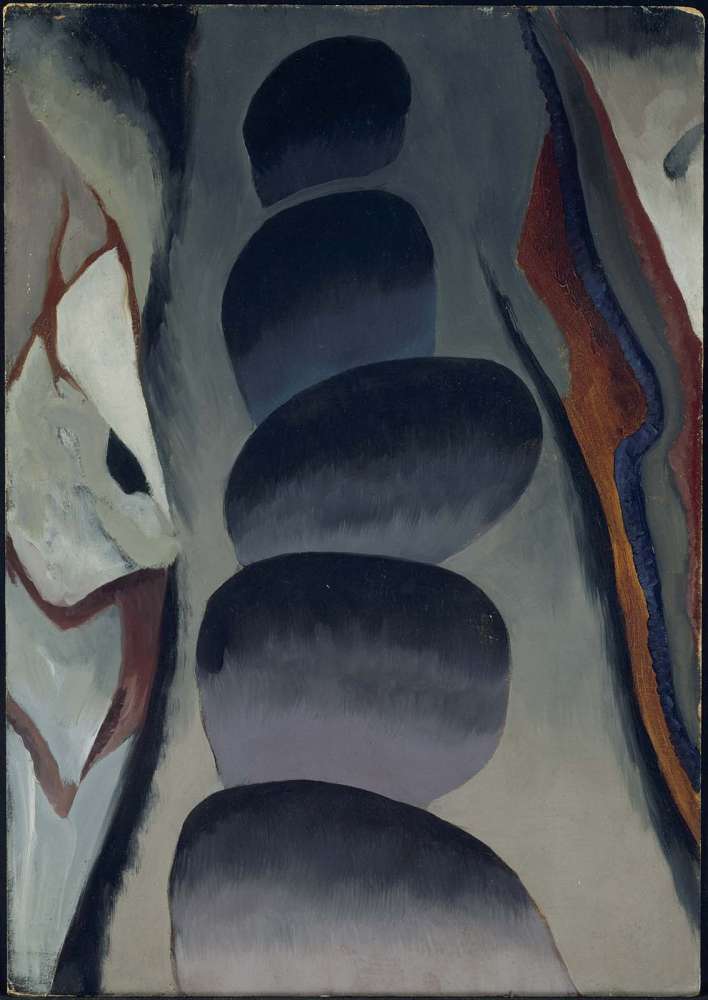

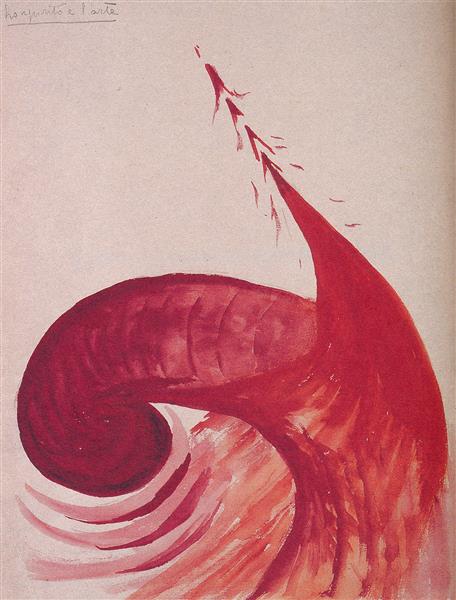

I’ve seen this painting titled “Cranial Reflections” and reproduced with different tones.

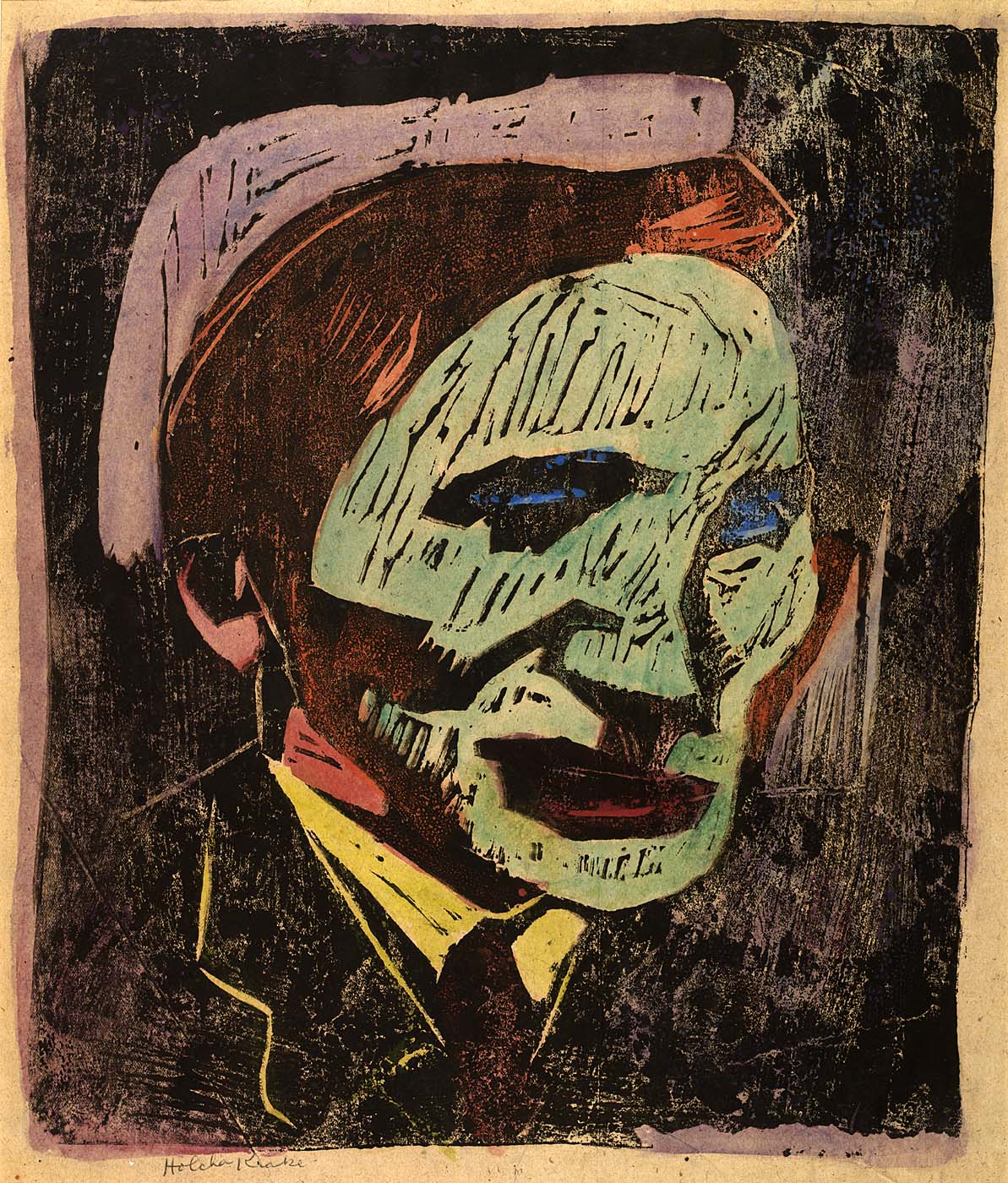

Johnson was one of the nation’s foremost African-American artists and a major figure in 20th-century American art.

Also see…

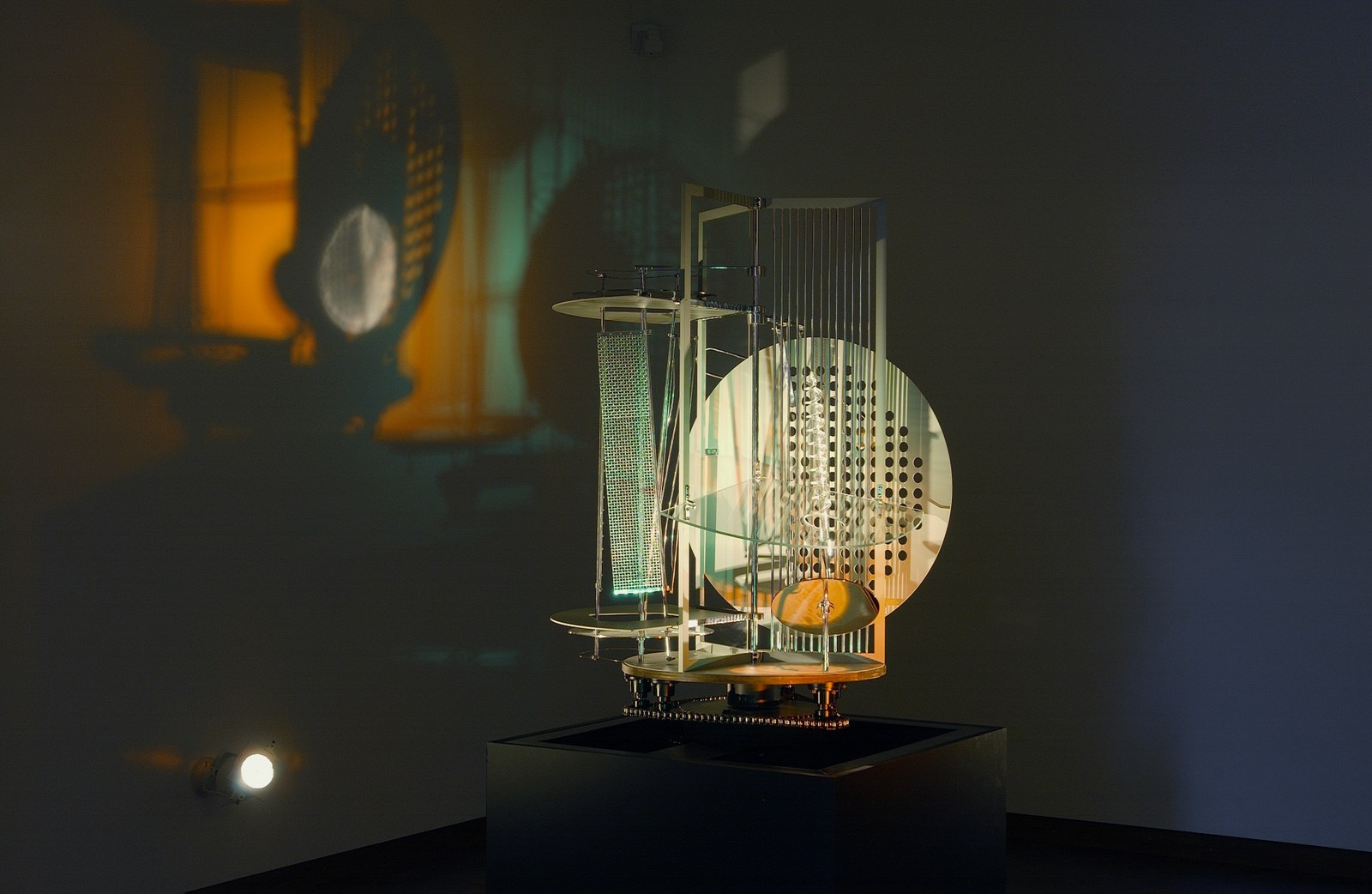

Shown here is a 1970 replica.

MORE RADIUM AGE SCI FI ON HILOBROW: RADIUM AGE SERIES from THE MIT PRESS: In-depth info on each book in the series; a sneak peek at what’s coming in the months ahead; the secret identity of the series’ advisory panel; and more. | RADIUM AGE: TIMELINE: Notes on proto-sf publications and related events from 1900–1935. | RADIUM AGE POETRY: Proto-sf and science-related poetry from 1900–1935. | RADIUM AGE 100: A list (now somewhat outdated) of Josh’s 100 favorite proto-sf novels from the genre’s emergent Radium Age | SISTERS OF THE RADIUM AGE: A resource compiled by Lisa Yaszek.