SEMIOPUNK (27)

By:

November 1, 2024

An irregular, ongoing series of posts dedicated to surfacing examples (and predecessors) of the sf subgenre that HILOBROW was the first to name “semiopunk.”

BABEL (2022) | BABEL-17 (1966) | CAMP CONCENTRATION (1968) | A CANTICLE FOR LEIBOWITZ (1959) | CAT’S CRADLE (1963) | COSMONAUT KEEP (2000) | THE DIFFERENT GIRL (2013) | DOOM PATROL (1987–91) | THE EINSTEIN INTERSECTION (1967) | EMBASSYTOWN (2011) | ENGINE SUMMER (1979) | EXPLOITS AND OPINIONS OF DR. FAUSTROLL, PATAPHYSICIAN (1911) | FEERSUM ENDJINN (1994) | FLATLAND (1884) | FRIDAY (1982) | LE GARAGE HERMÉTIQUE (1976–79) | THE GLASS BEAD GAME (1943) | GLASSHOUSE (2006) | GRAVITY’S RAINBOW (1973) | THE HAMPDENSHIRE WONDER (1911) | LORD OF LIGHT (1967) | THE MAN WITH SIX SENSES (1927) | THE MOUNTAIN IN THE SEA (2022) | NINEFOX GAMBIT (2016) | ODD JOHN (1935) | PATTERN RECOGNITION (2003) | THE PLAYER OF GAMES (1988) | RIDDLEY WALKER (1980) | RODERICK (1980–83) | SNOW CRASH (1992) | THE SOFT MACHINE (1961) | SOLARIS (1961) | THE SPACE MERCHANTS (1953) | THE THREE STIGMATA OF PALMER ELDRITCH (1964) | TIME OUT OF JOINT (1959) | UBIK (1969) | VALIS (1981) | A VOYAGE TO ARCTURUS (1920) | VURT (1993) | WHITE NOISE (1985).

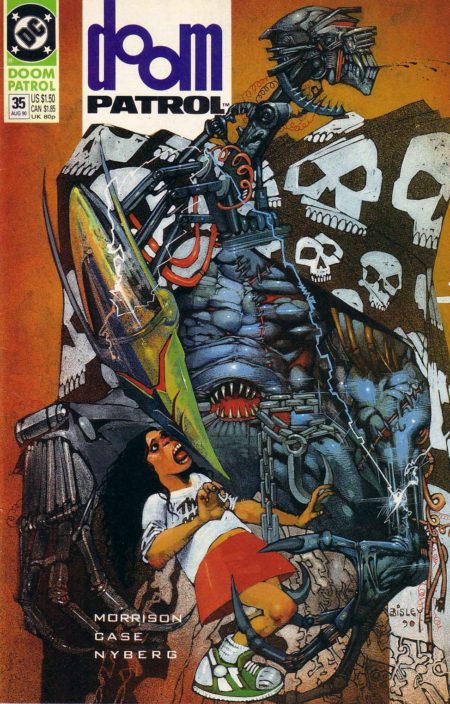

DOOM PATROL

In 1963, the DC comic book My Greatest Adventure, an adventure anthology, was converted to a superhero format — and DC writer Arnold Drake was assigned the task of dreaming up a brand-new superhero team. After about an hour, Drake would later recount, he proposed…

…the basic idea about the man in the wheelchair who is the great brain, and runs this group of superheroes who hate being superheroes. That was the new aspect. That was the thing that made Doom Patrol different, these people hated being superheroes.

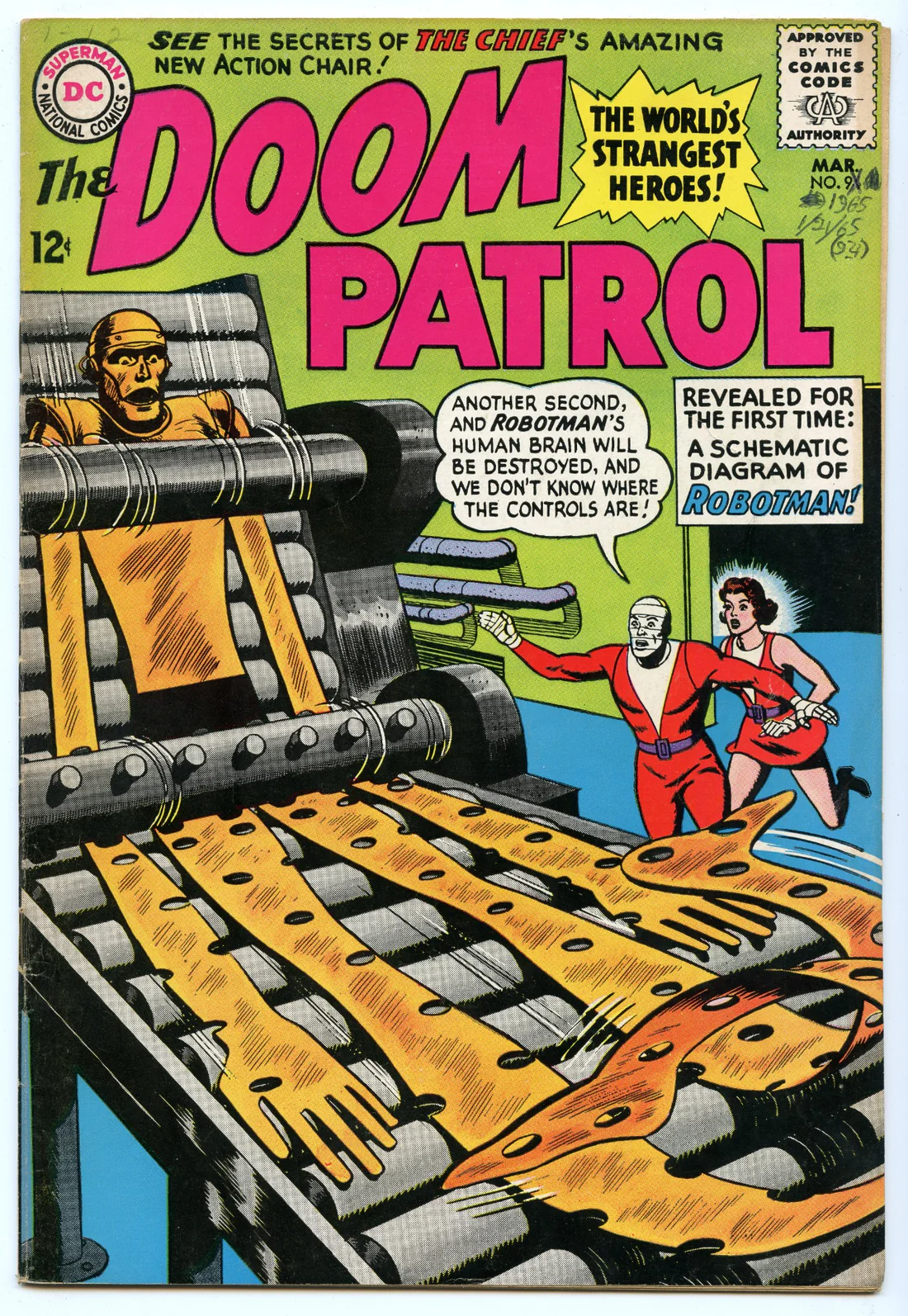

“Le Poète est semblable au prince des nuées/Qui hante la tempête et se rit de l’archer,” laments Baudelaire in “L’Albatros.” “Exilé sur le sol au milieu des huées,/Ses ailes de géant l’empêchent de marcher.” Like Baudelaire’s albatross, the members of Drake’s Doom Patrol are extraordinary: the Chief is a wealthy, brilliant scientist-inventor; Robotman, a former daredevil and race-car driver turned cyborg; Elasti-Girl, a former athlete and actress who can expand or shrink her body at will; and Negative Man, a former test pilot who can release a negatively charged energy being from his body. Also like the albatross, however, their extraordinary qualities render them disabled, even freakish. The Doom Patrol’s members perceive their so-called gifts as a curse; they are doomed to a life of alienation.

A kind of missing link between Marvel’s Fantastic Four (three men and a woman; one member has stretching powers, another has great strength but is trapped in an inhuman orange body; the form of a third seems ablaze with energy) and Marvel’s X-Men (misfit superheroes, hidden away from society, led by a wheelchair-bound man of preternatural intelligence), the original Doom Patrol first appeared in My Greatest Adventure #80 (June 1963); the series was re-titled Doom Patrol as of issue #86.

When the eccentric, often surreal comic — the Doom Patrol’s adventures were bizarre, even zany one — faced cancellation in 1968, after 4+ issues, Drake killed the team off (!) in issue #121. Self-pitying and/or self-loathing superheroes, the Doom Patrol were ahead of their time.

In 1989, the Doom Patrol’s moment arrived.

Grant Morrison, the Scottish writer who — along with Neil Gaiman, Peter Milligan, Jamie Delano, and Alan Moore — had helped spearhead the British invasion of DC Comics a couple of years earlier, was tapped to take over DC’s latest revived Doom Patrol series — one that featured less tortured, more conventional superheroes — which had been launched two years earlier. Important note: DC stopped submitting the title to the CCA for approval around this time, too.

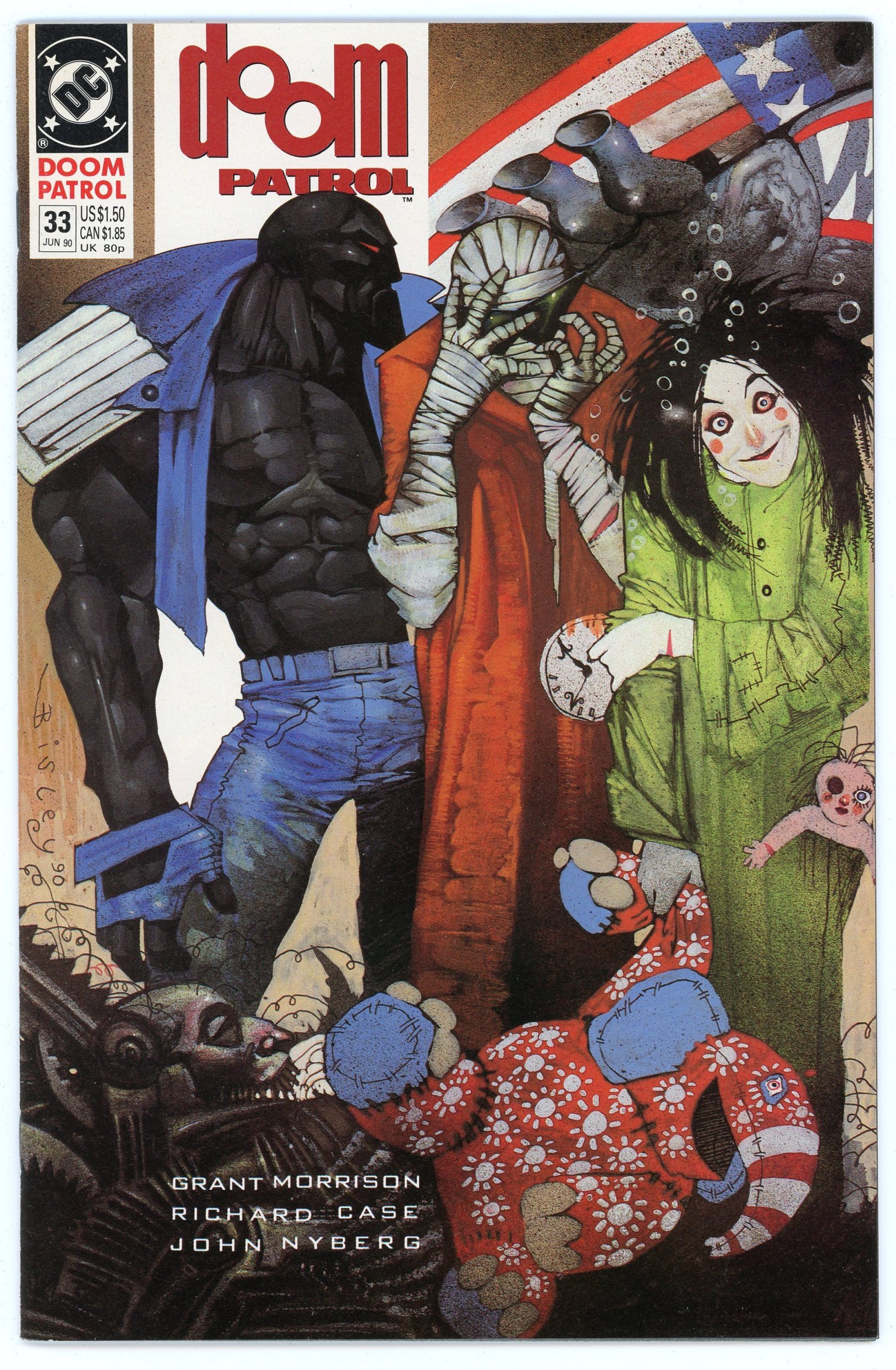

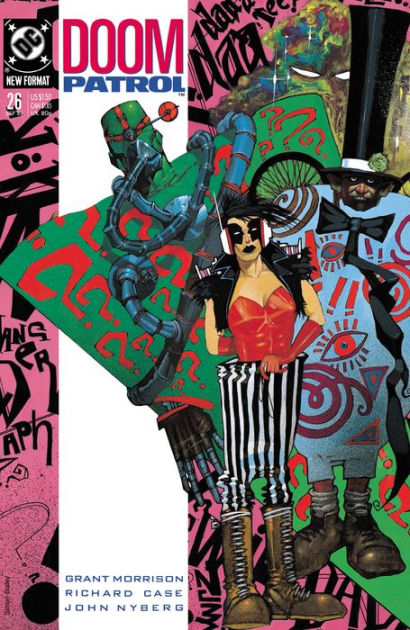

Morrison’s postmodernist, meta-textual “run” on Doom Patrol (issues #19–63), a tour de force introducing comics readers to Dada, Borges, and the cut-up technique pioneered by William S. Burroughs and Brion Gysin, would prove to be far more bizarre than the original. (In fact, Drake would later say that Morrison’s was the only subsequent run on Doom Patrol to reflect the intent of the original series.) The original series’ Chief and Robotman (a brain trapped in a body without nerves; here mostly called by his name, Cliff Steele) are joined by Rebis (an amalgamation of the original Negative Man, Larry Tainor; Eleanor Poole, a doctor who was taking care of him; and the Negative Spirit, a cosmic entity); Crazy Jane (a victim of sexual abuse with multiple personalities, each of which employs a different superpower); Dorothy (an ape-faced teen with the ability to bring powerful “imaginary friends” to life); and Joshua Clay (formerly Tempest, the team’s doctor with energy-projecting abilities). Later, this misfit crew would also include Danny the Street, a sentient neighborhood that would serve as their base of operations.

I’ve written elsewhere that Morrison is one of the great Scottish fabulists. Like Robert Louis Stevenson, Walter Scott, Arthur Conan Doyle, John Buchan, and others, he knows how to keep us on the edge of our collective seat. Unlike these predecessors, however, in these stories Morrison gives us a world in which objective truth is unknowable, illusion and reality are interchangeable.

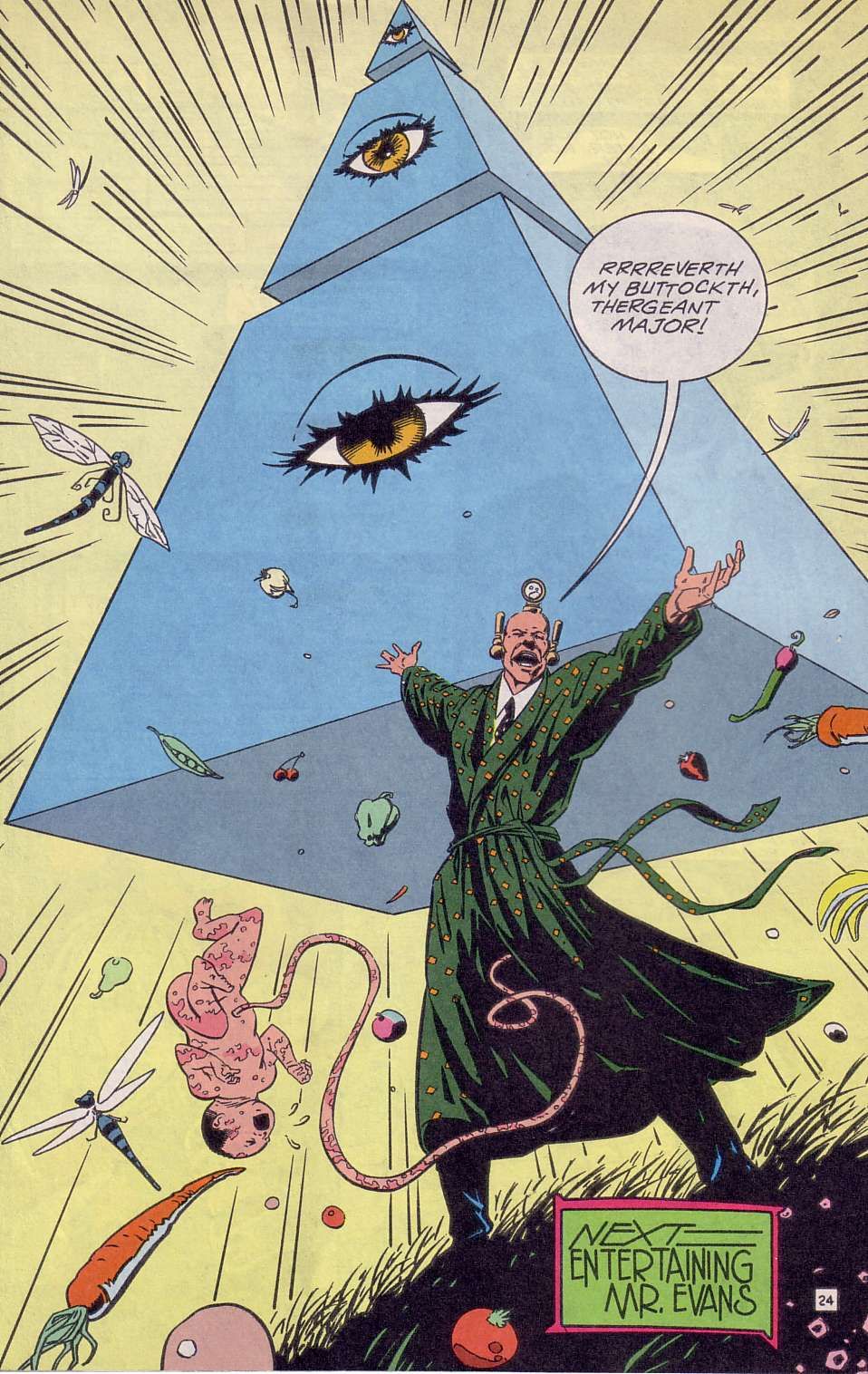

Morrison’s run on Doom Patrol, we read in Steven Shaviro’s Doom Patrols,

rightly depicts the Pentagon as headquarters of a bizarre supernatural conspiracy aiming to institute worldwide standardization and puritanical repression. We’re continually meeting sinister forces like the Men From NOWHERE, “normalcy agents” whose mission is to “eradicate eccentricities, anomalies, and peculiarities wherever we find them.” Stability, normality, conformity, and everyday boredom are always the real enemies; DOOM PATROL deploys against them its vision of crazed flux in a decentered, goofily hyperreal world. It provides an exhilarating mixture of kitschy nonchalance and schizoid exaggeration; it is multilinear, eclectic, and self-consciously absurdist. Of course, it is garishly illustrated, with aggressive outlines and high-contrast colors, in a style that ranges from the hallucinogenic to the Gothic. The book features a shifting cast of characters, and wildly proliferating plotlines; its tone swings between parody and horror, between extravagant silliness, wickedly barbed satire, mystical revelation, and apocalyptic dread. And through it all, DOOM PATROL shows a marked fondness for puns and wordplay, as well as for the consumption of psychedelic drugs.

Ultimately, the Doom Patrol’s weirdness proves to be the key to its effectiveness: They often team up with so-called villains in order to combat the neo-fascist, Foucauldian forces that police sexual identity and gender norms. (In the first few issues, the Doom Patrol battles the alien Scissormen — Struwwelpeter-like inquisitors who worship a god that exists at the crossroads where realities meet, and whose cut-up dialogue is trippy. And then there’s Red Jack, a near-omnipotent, pain-sustained being who believes he is the creator of the universe… and also Jack the Ripper. And the Brotherhood Of Dada.) Richard Case’s trippy art direction is simultaneously engaging and nightmare-inducing.

I mentioned Foucault, earlier…. What worries Foucault, we read in his History of Sexuality, is the monotonous sameness — across cultures and eras — of sexual practices and behaviors. Humankind prides itself on being imaginative and inventive, but much of what passes for outré and radical is on the surface of things. Beneath the surface, our behavior remains eternally determined by undetectable forces — constraining us into what Shaviro describes as “the same positions, the same rhythms, the same rituals, the same binary divisions of gender.”

Semioticians will appreciate Morrison’s efforts to pry the lid off Western culture, in his run on Doom Patrol — his effort to expose the determining network of forces that continually mutate (in truly imaginative and inventive ways) in order to control us, supposedly for our own good. In the struggle against such near-omnipotent, pain-sustained forces, things will get weird. Heroes may be villainous and villains heroic. Perhaps only a freak is cut out for this sort of work.

JOSH GLENN’S *BEST ADVENTURES* LISTS: BEST 250 ADVENTURES OF THE 20TH CENTURY | 100 BEST OUGHTS ADVENTURES | 100 BEST RADIUM AGE (PROTO-)SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST TEENS ADVENTURES | 100 BEST TWENTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST THIRTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST GOLDEN AGE SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST FORTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST FIFTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST SIXTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST NEW WAVE SCI FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST SEVENTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST EIGHTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST DIAMOND AGE SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST NINETIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST HADRON AGE SCI-FI ADVENTURES.