OFF-TOPIC (65)

By:

October 29, 2024

Off-Topic brings you over-the-transom, on-tangent essays, dialogues and subjective scholarship on an occasional, impulsive basis. For election season, a panel of mighty pens to discuss what creative decision-making looks like…

It’s a paradox of human hierarchy that we rely on two different sets of people to make things happen and to dream what can be. Fantasy without vision gets us trapped in real-life circumstances we never really wanted. Every few years at election time, we are offered the prospect of converting our aspirations to concrete circumstance; typically, the ambitions of one person are superimposed on the future we can see ourselves in. But the mutually reinforced delusions of social media now grant us unrealities to reside in. It’s the role of the creative mind to speak fiction to power, imagining stories that reflect light on real life rather than tell tales that displace it, for at least as far back as the model society of Plato’s The Republic or African griots trying to subtly influence their patrons with parables about being your best self. The true news, of what people fear are the logical consequences of current politics and beliefs, what they envision as the achievable alternative, and what metaphorical forms the forces arrayed against them and the potential inside themselves could take, is found in the work of the attentive visionaries I contacted for this conversation.

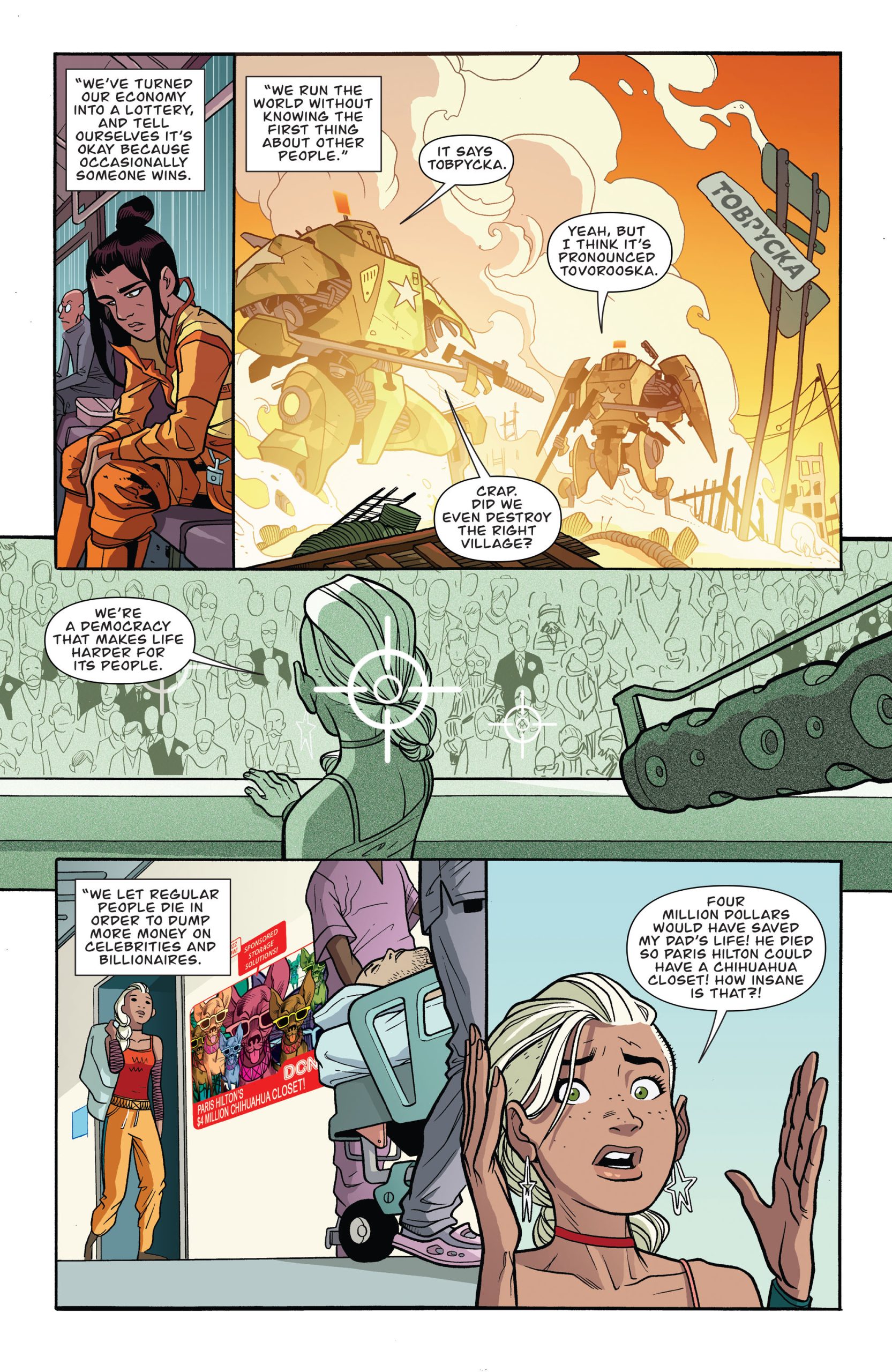

Humorist and humanist Mark Russell entered comics and politics at the same time with PREZ, a plausibly absurd reboot of DC’s 1970s comic about a teenage president, this time chosen in a social media poll. He’s since won over readers across a surprising spectrum with Second Coming (Ahoy), a daring and thoughtful reflection on humility and worship which was rejected by DC and co-stars Jesus Christ, as well as the controversial, heartbreaking Exit, Stage Left!: The Snagglepuss Chronicles (incarnating the fussy cartoon lion as a tragic Southern gay playwright in the mid-20th century), and fascinating allegories of class and conflicted human interest from the dramatic to the ridiculous like Billionaire Island (Ahoy), Not All Robots (AWA), Death Ratio’d (AWA) and Travelling to Mars (ABLAZE).

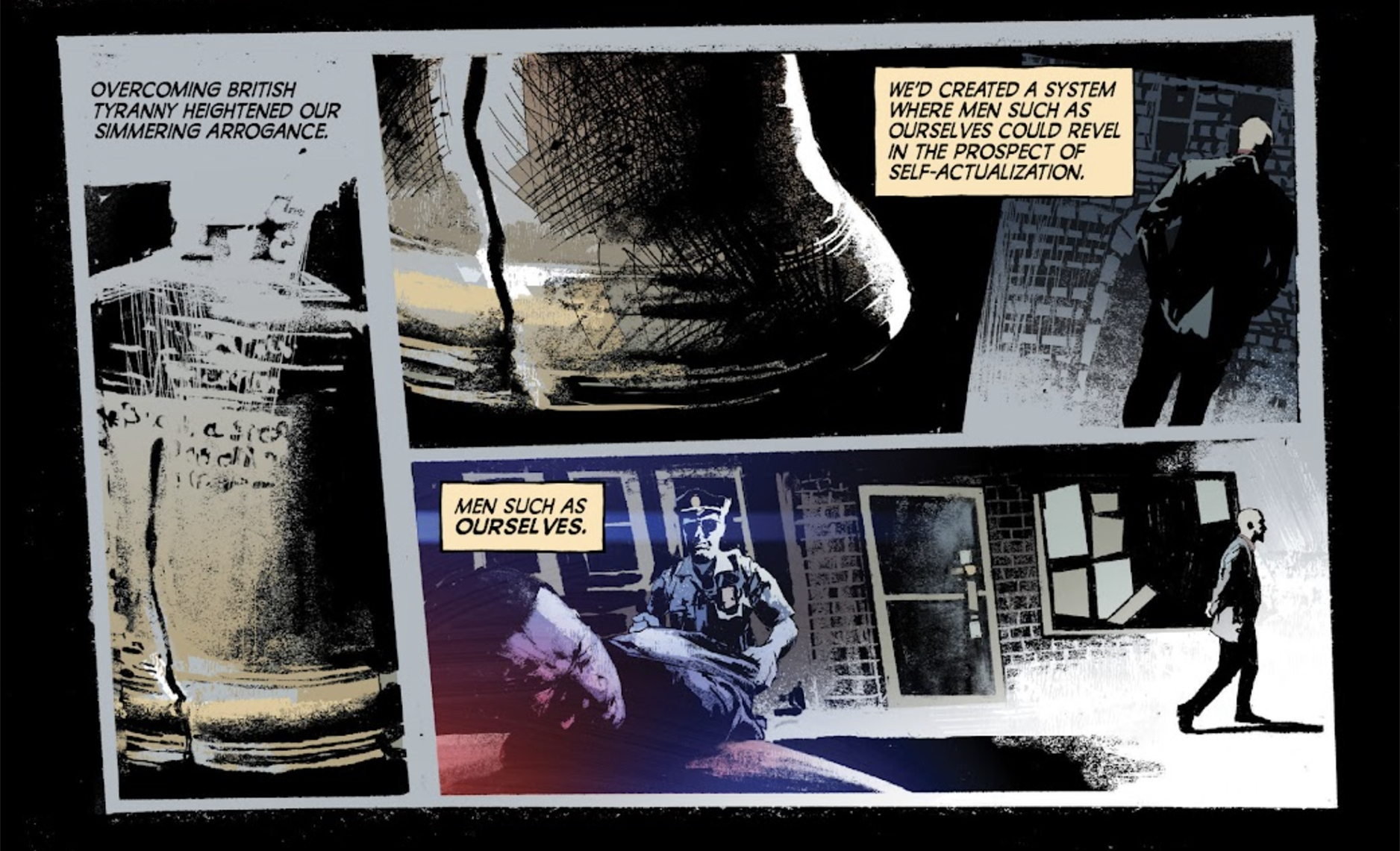

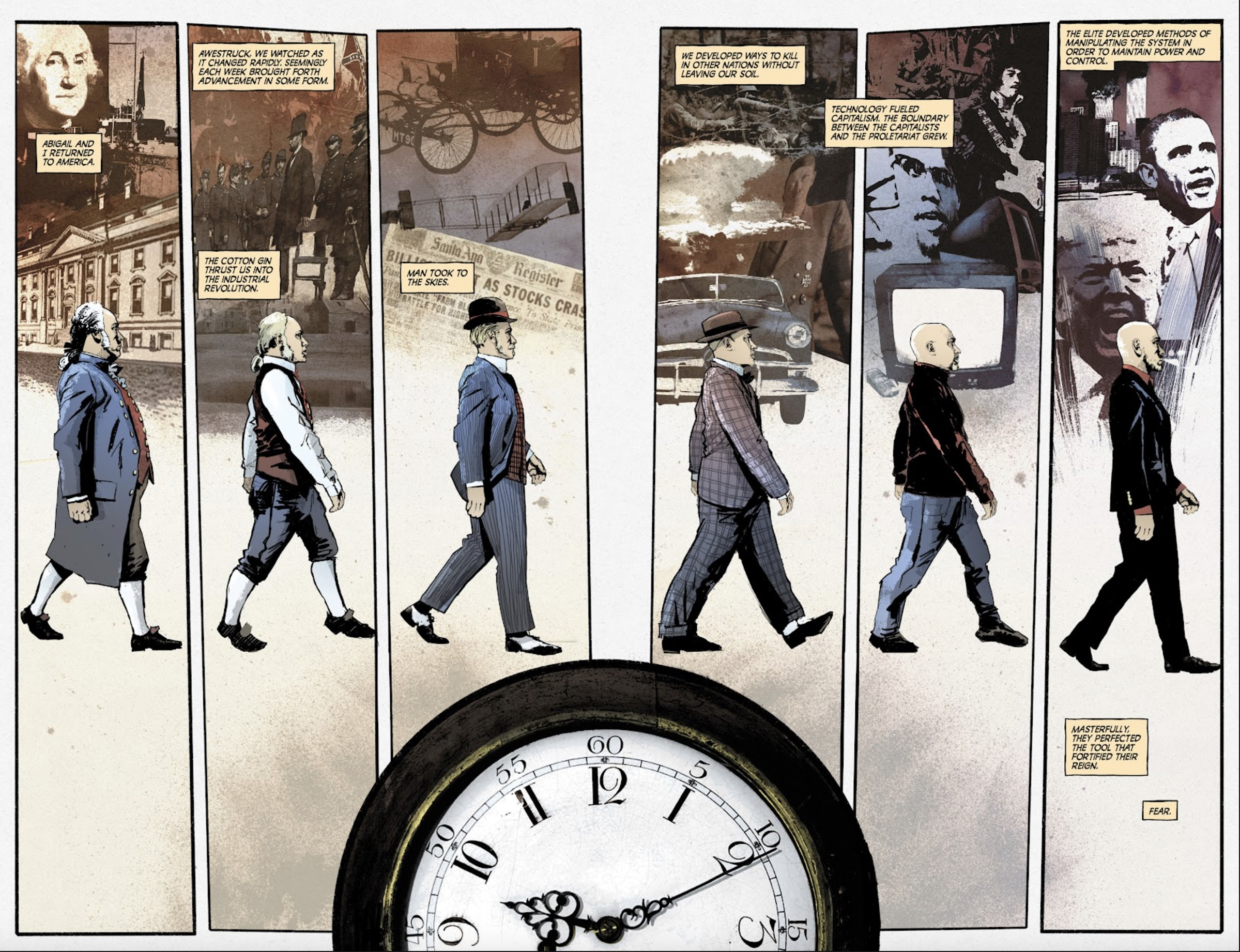

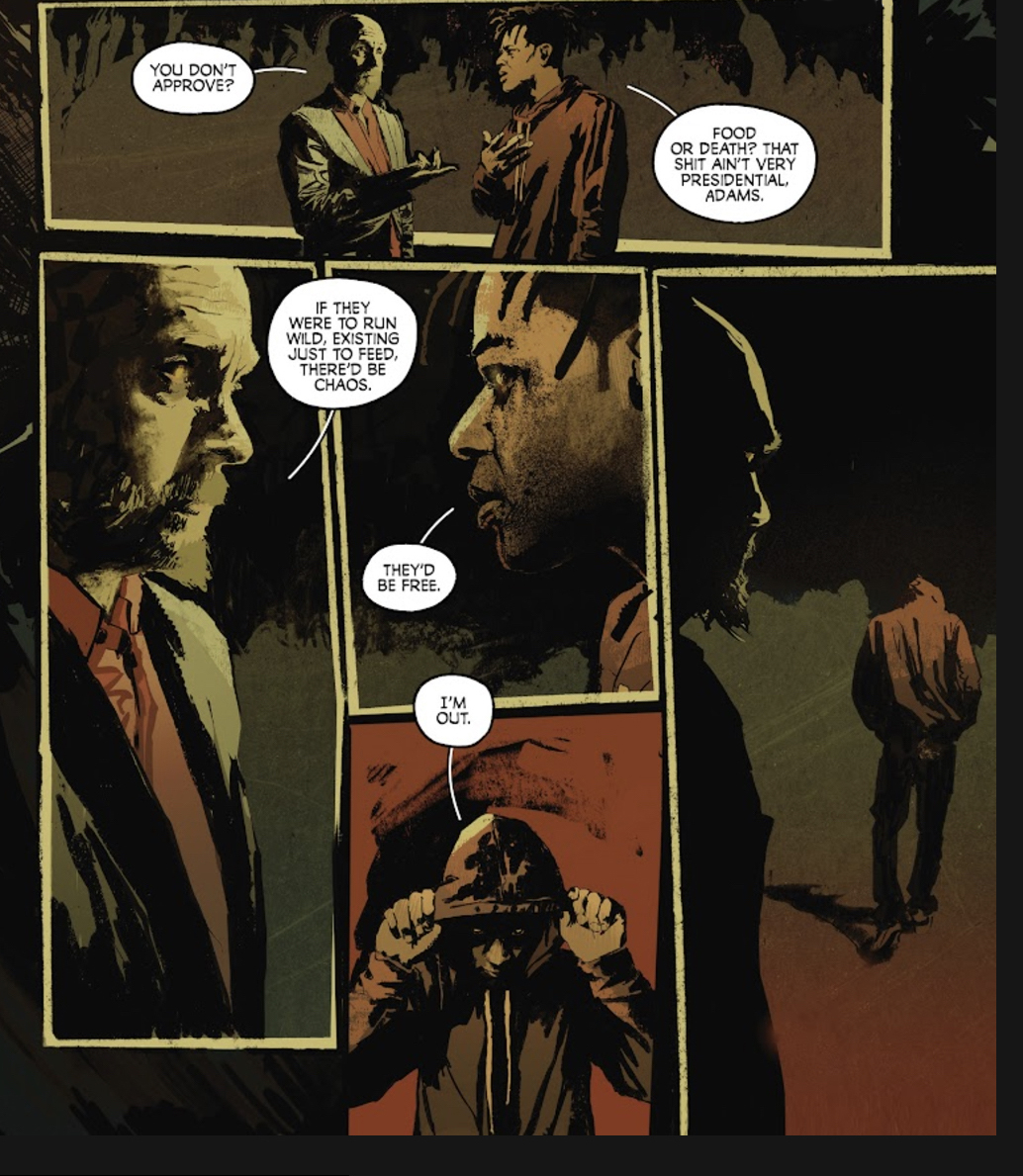

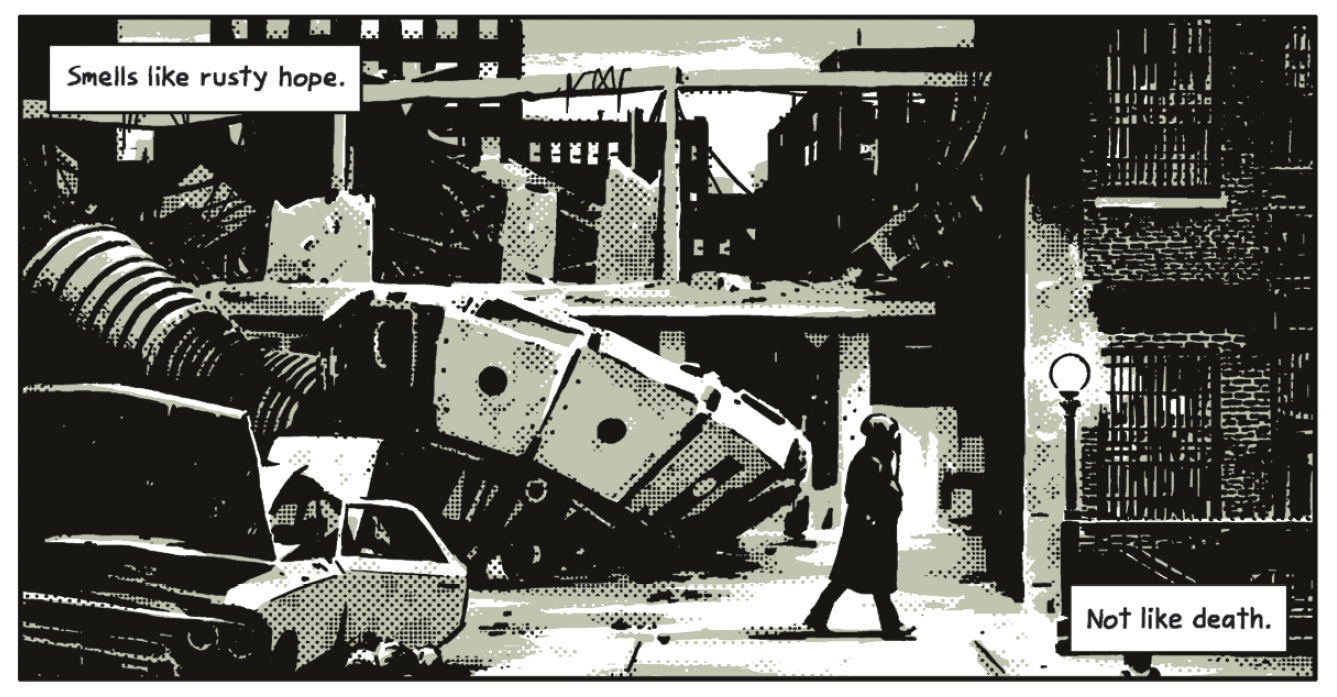

One of pop’s most inexhaustible storytellers and thoughtful commentators, Rodney Barnes has expanded the cultural conversation from humor to history to horror as everything from head writer on The Boondocks to writer and producer on Hulu’s Wu-Tang and HBO’s Lakers Dynasty series to host of the Run, Fool! scary stories podcast. He is best known in comics for his longrunning Killadelphia series (at Image) and its spinoff universe, in which the sins and flaws that mark America’s creation continue to haunt us in the literal form of Founding Fathers risen as vampires, with new ideas and old hubris in a plan to re-rule the country that first plays out as an apocalyptic contest of deceptive good, ambiguous evil, and many uncertain shades-in-between, with American democracy’s birthplace as the battleground.

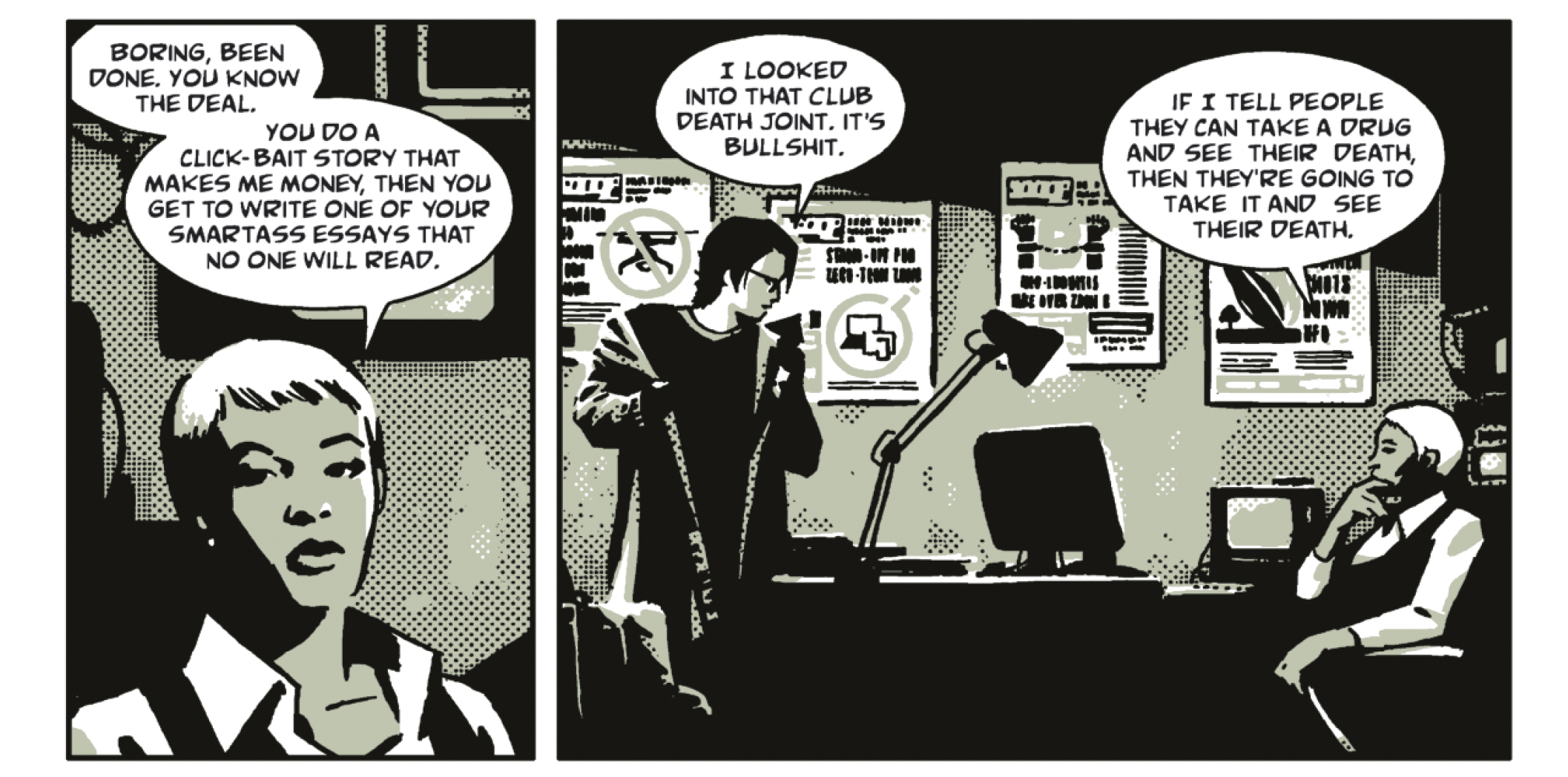

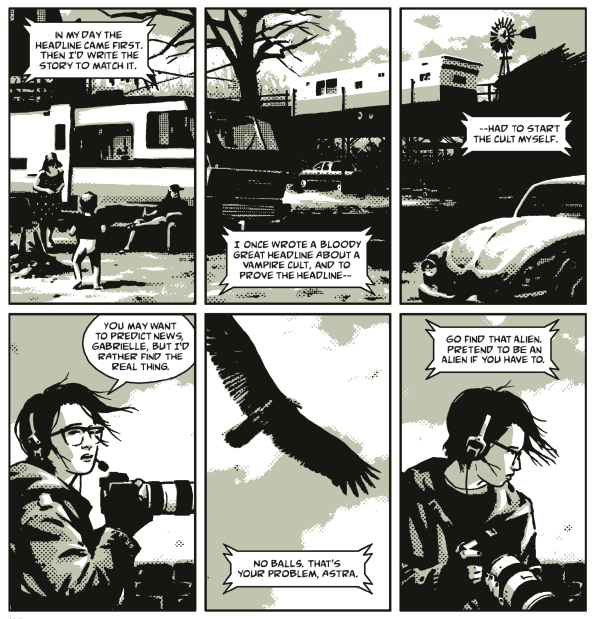

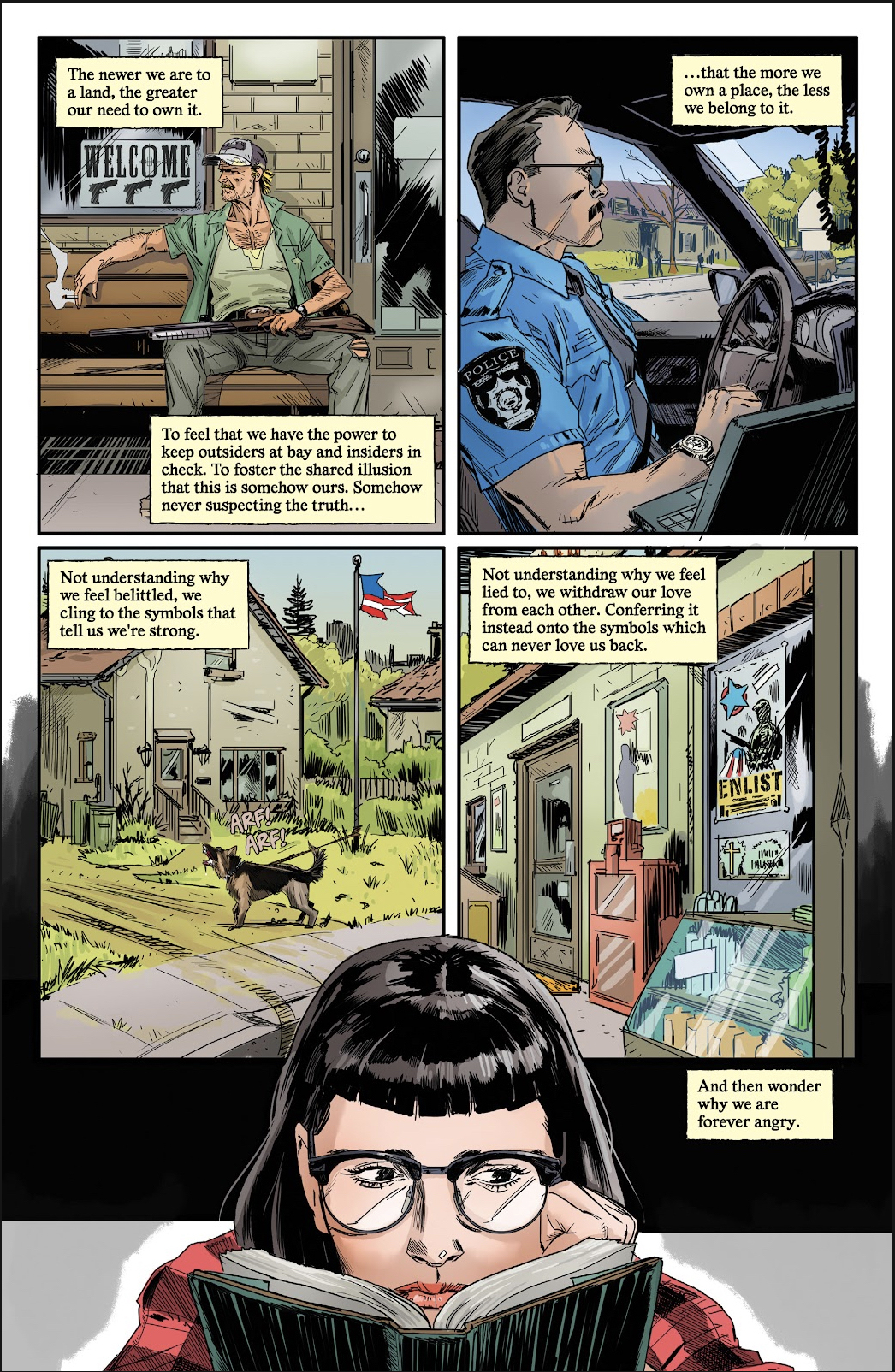

The margins take the center of the panel in the comics of Annie Nocenti, documentary filmmaker, creator and curator of public art, and legendary graphic scriptwriter. Her stories are a polyphony of subcultures and alternative viewpoints lending innovative structures to narratives of transformative states of consciousness (Klarion (DC), Captain Marvel: Dark Tempest (Marvel)) and being (Kid Eternity (Vertigo)) and forms of society (Catwoman (DC)). Also transforming franchised properties with a psychoactive, philosophy-slam style, her own creations like Ruby Falls and The Seeds bring the hidden and the new to our eyes, remapping the America left out of history; Ruby Falls by tracing a vanishing smalltown-outpost way of life and the ways in which it could be unspokenly deadly, and The Seeds by pacing ahead to a near-future world in social and environmental collapse but reforming itself out of the novel ideas and fertile difference of its unvalued masses.

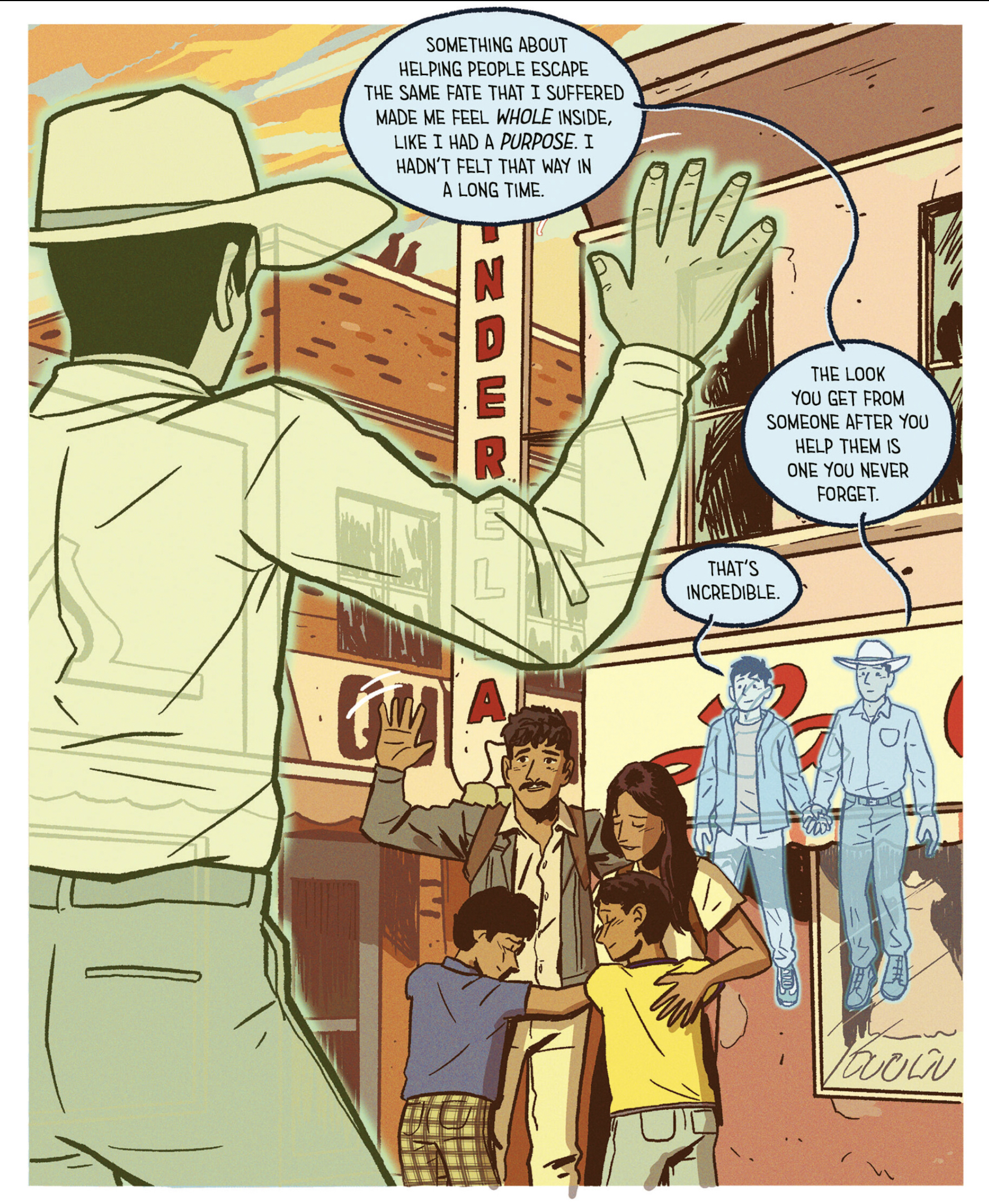

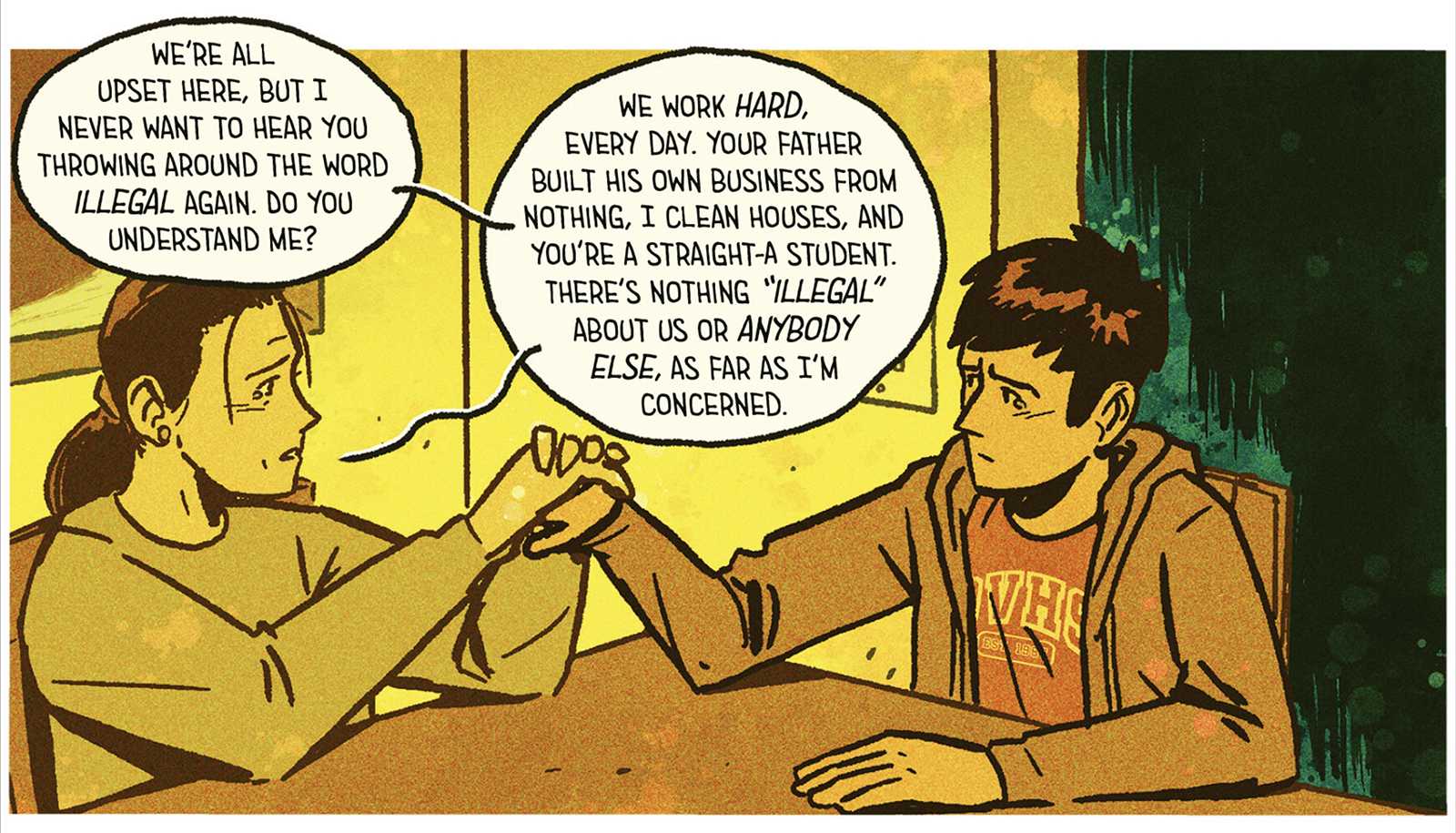

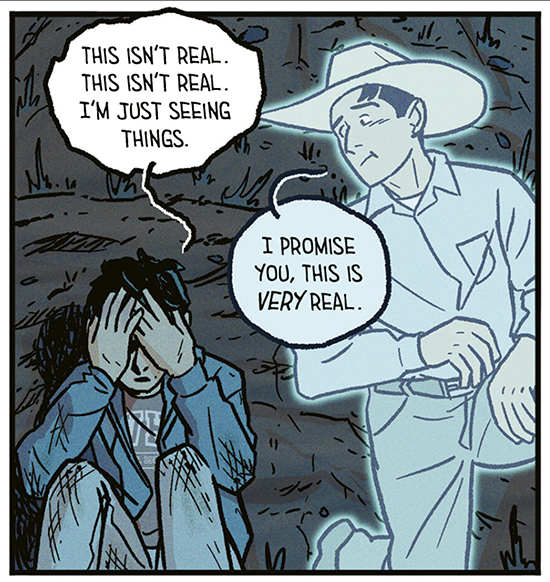

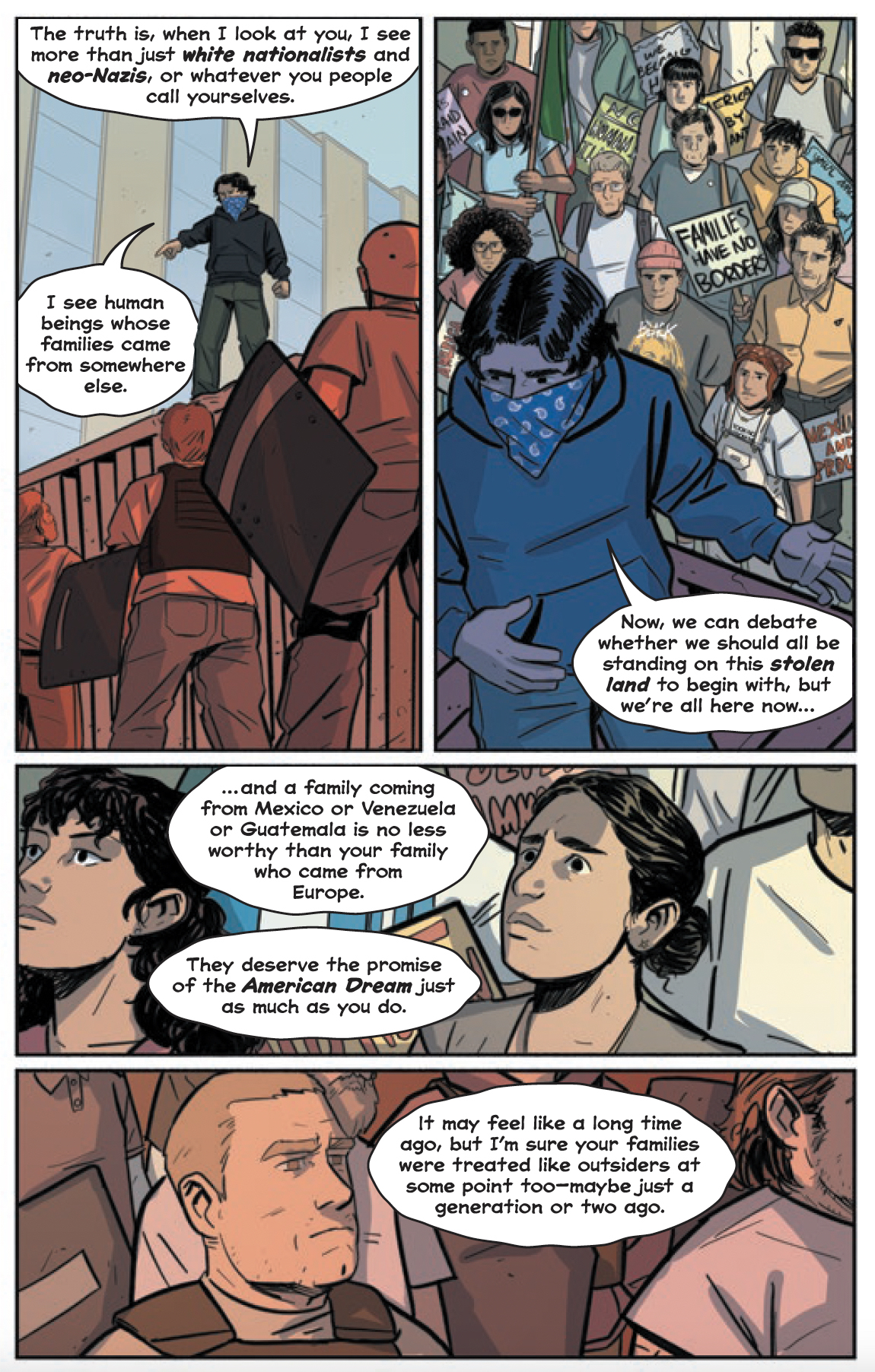

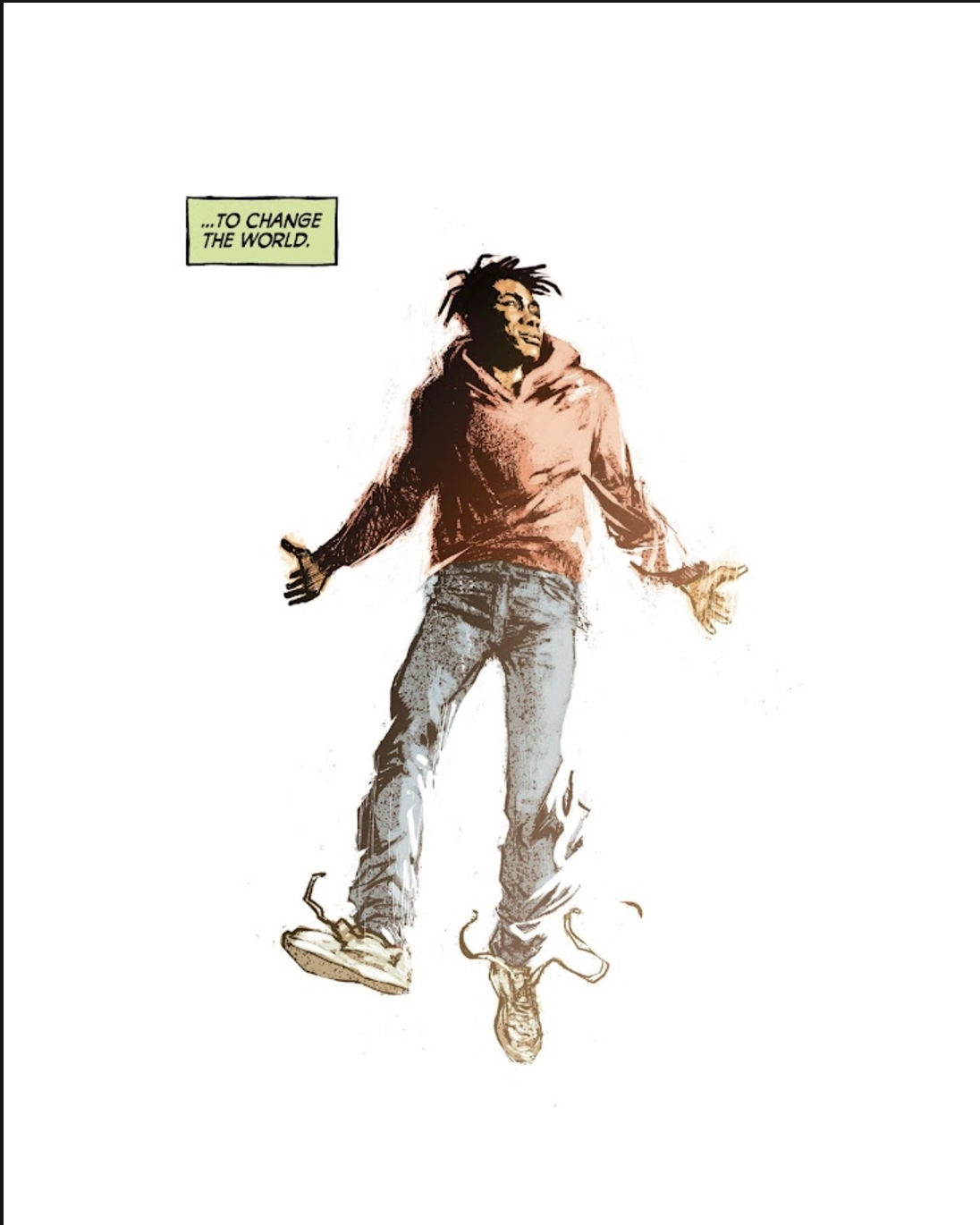

Julio Anta tells stories on behalf of one of the communities most told myths about, the emerging American majority of immigrants, set up as the villains of ulterior politicians’ narratives but recentered as protagonists whose perspective we can share. His series HOME (Image) follows undocumented families stalked by ICE and manifesting superpowers which are not the social empowerment that really keeps everyone safe; the Eisner-nominated Frontera (HarperAlley) is a new American odyssey of crossings between cultures and back and forth across the threshold of life, with ancestral spirits both figurative and supernatural accompanying the forward journey; his new YA graphic novel for DC, Blue Beetle: This Land Is Our Land makes the outerspace-artifact that seeks to control the title hero a brilliant parable for embracing those outside of you and ignoring the voices in your head. Anta operates on the border of the believable and pushes the line of what’s possible.

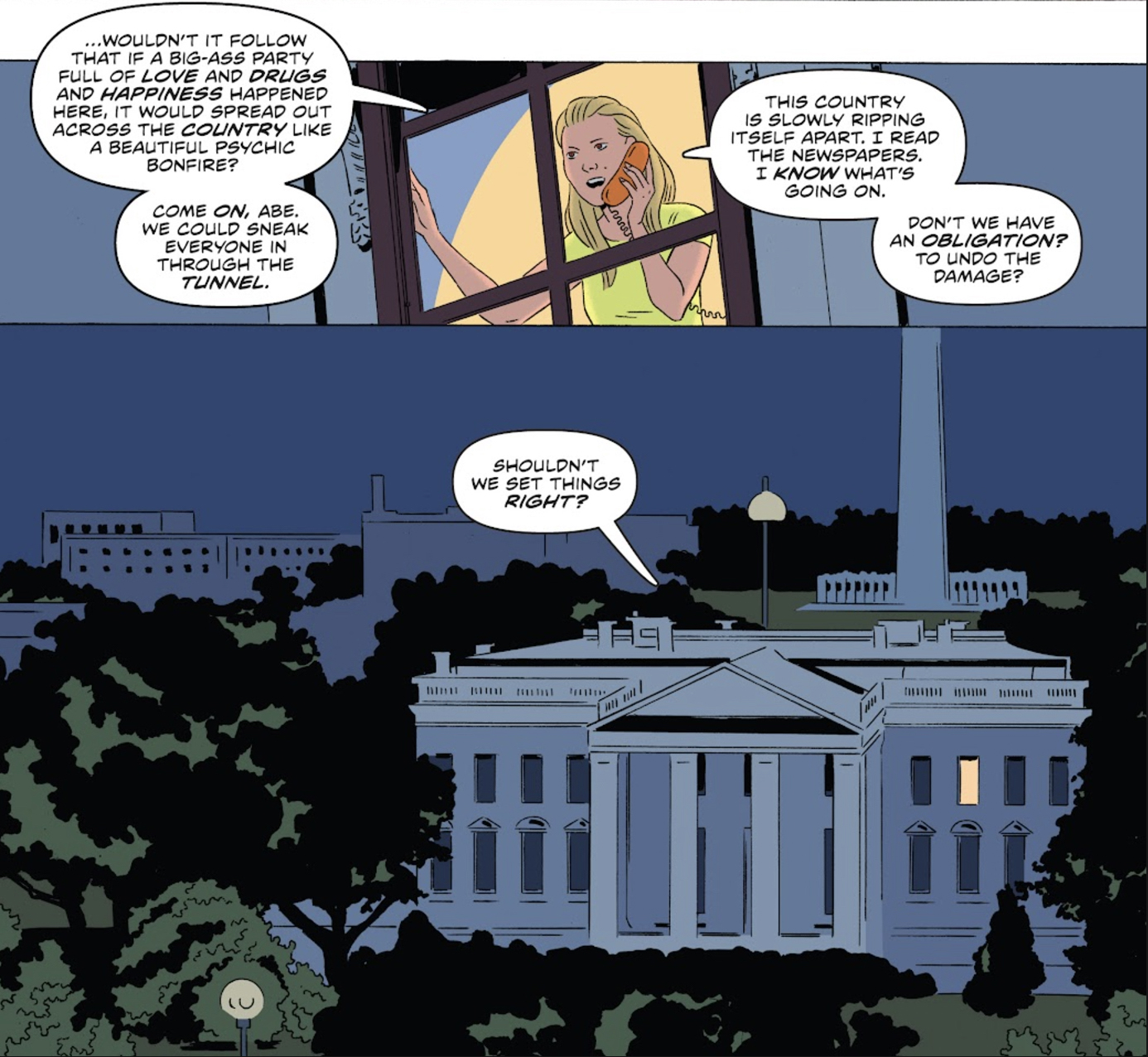

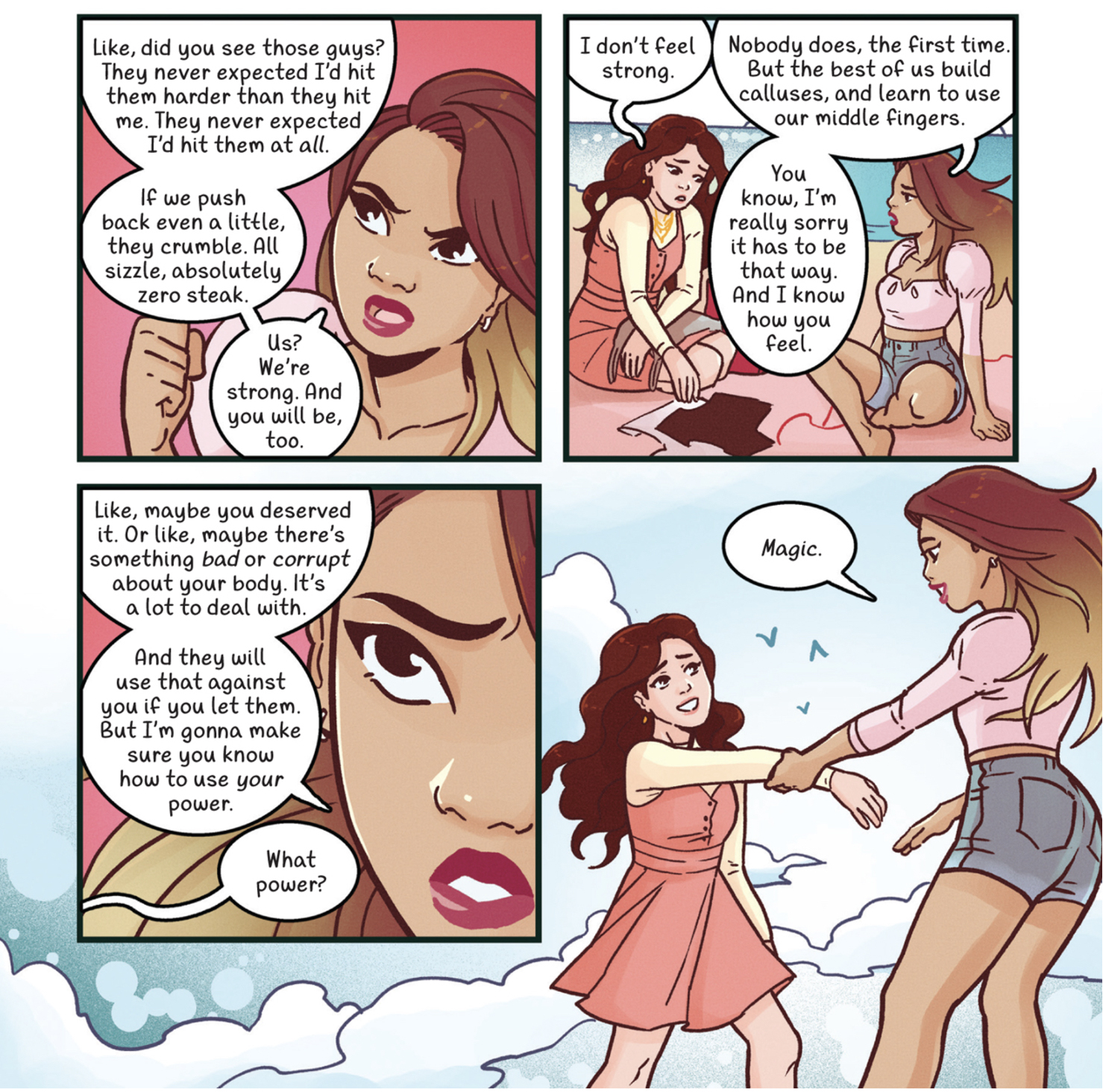

Writing comics with a prophetic voice and contending in public forums with a fearless contrarian eye, Magdalene Visaggio draws drama and often hilarity from characters who insist on living the life unexpected of them (Lost on Planet Earth (ComiXology)), navigate and transcend unknown boundaries of identity (Eternity Girl (DC)) and validate infinite difference (Dazzler: X-Song (Marvel)), and travel the fractured cosmos in blockbuster metaphors for navigating the cacophony of 21st century culture (Kim & Kim (Black Mask), Vagrant Queen (Vault), etc., etc.). She’s equally at home with the mindbending conjectural physics of a post-space-opera like Galaxy of Madness (Mad Cave) and the heart-wise interpersonal navigations of a dram-com about the struggle to be yourself either trans or cis, Girlmode (HarperAlley); she also got away with one issue of Marilyn Manor (IDW), about a hellraising First Daughter who chases down hidden history and sci-fi intrigues in the catacombs of the White House.

My own less subtextually political comics include contributions to ComicMix’s Ringo Award-winning reproductive-choice-themed anthology Mine! and their perpetually forthcoming enviro anthology Crisis on Our Only Earth, and stories in the headline-making Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez and the Freshman Force and its sequel The Squad Special (Devil’s Due), though in this case I’m just your humble Sunday-morning pundit-show host. The conversation was conducted by Zoom on September 27, 2024…

HILOBROW: There is a long history of… either feeling we have to couch political issues in creative settings, or perhaps it’s just our instinct and nature to dramatize things in order to make certain connections. Particularly in a book like PREZ and I think in a lot of your other works too, Mark, we find almost this model oratory, the kinds of things I would like to hear people who are actually in power say. What do you feel about this being a matter of wish-fulfillment, or a stealthy attempt to set an example for people who would presume to actually be in power, and also what possible effect do you think words can have on public action and political dynamics?

RUSSELL: There are scenes [of mine] where characters just give speeches that you’d probably never hear in real life, just because they’re blunt and to the point; but [PREZ] and probably everything I’ve written since has been kind of predicated on the idea that there’s really no time for subtlety. We’re in a lifeboat situation, there’s no time to make clever allusions to the lifeboat, we need to tell people where the lifeboat is, we need to tell them that the boat is sinking. And I think some of the criticisms, particularly early on in my career, were that “Oh this is heavy-handed,” or “this is just like a manifesto”; y’know, guilty as charged, but I think we’re at that point, where we need to be pointing people to the exit, because our window of opportunity for change is rapidly closing.

NOCENTI: It’s interesting to think about this, because I was just reading that, is it the 25th anniversary of The West Wing?

ANTA: It is, yeah.

NOCENTI: There’s been some funny press around it, because I think some people use The West Wing as kind of a wet dream: “Oh, this is how democracy actually functions.” But it’s not realistic, it’s wishful thinking, that democracy could function this way. I agree with what Mark just said about things being urgent. With my graphic novel The Seeds, there isn’t much urgency, because the angle I took was more hopeful, in that there will be survivors of whatever comes, and it’s really about what comes next. I try to maintain friendships with my friends that have gone all the way to the right, and they are openly talking about civil war if Trump doesn’t get elected. They use phrases like, “They’re already getting ready to steal it from us” and they seem delighted by the fact that Kamala Harris could win, because then the civil war starts. So yes, it’s dark times; please point us to the lifeboat.

ANTA: Annie, I’m glad you brought up The West Wing because I was thinking about that as Mark was answering also; and I’m also of the generation that kind of grew up watching The West Wing. And for that being in the George Bush era, watching this show that felt like something that could be in the future and then getting Obama, in the first election I was able to vote in, and then everything that’s happened since, and from my perspective, beginning with Obama when it comes to the issues I’m passionate about, which are often border issues, becoming extremely disenchanted by what’s happened politically. And how my work, which is different than Mark’s work, has reflected less of the world that I wish could be, and more so of the world that we’re in, and regular people dealing within those situations; generally young people and teenagers working through that reality and this grounded reality that we live it. But you know I don’t think I would be in this place now if I didn’t grow up watching a show like The West Wing, or was in my college years during the Obama Administration and saw the things I was passionate about not necessarily change and maybe get worse in many ways, but yeah I think it’s different approaches to [engaging] politics in the work.

NOCENTI: I think Obama is a good example… I was living in Haiti when Obama got elected. I was with a lot of Haitians and they responded to Obama’s election as if it was their president too, there was a sense of the American presidency being a global president, in an odd way. And I haven’t felt that kind of excitement since Obama. And the anti-Obama people will say that no matter what you do, you slowly get the death by a thousand cuts, you get ground down by corporate politics, and you end up making compromises every day of your presidency until you’re co-opted, which is why people like to call Obama a neoliberal president.

HILOBROW: And we’re joined by Rodney Barnes! The question we had been starting out with, Rodney, was the idea of couching political issues in fiction, and whether there’s a hope of this being a model for how our actual officials could behave, if it’s like a handbook for citizenship… it’s pertinent in your case because, with 200 years’ hindsight you’ve been able to channel the voices of the Founding Fathers, even though, to Annie’s point about even liberal politicians being compromised, we’re hearing John Adams and George Washington [acknowledge] what mistakes they made and yet their solution is One Nation Under Vampirism — so it’s not certain to me if that’s a metaphor for how things can’t change…

BARNES: I think it speaks to ego, a lot of times, and the limitations that come with being human. And power, what it does, how it transforms the psyche. That even if you have the best of intentions, sometimes that doesn’t always pan out in the way that you want it to. I look at Killadelphia as a cautionary tale; these are individuals who, I imagine, they were there at the founding of America, they’ve seen it for a couple of hundred years, they’ve watched it, they’ve walked through, there’s a couple of panels where I show John Adams walking through history and just watching everything take place. And even having witnessed the result of decisions that were made, still he gives way to this idealism that I don’t know if it takes everyone into consideration. Which is [what] I think sometimes America struggles with. It seems like the whole trickle-down economics thing, that idea that corporate America will at some point do the right thing for everybody, I’ve never seen that work over the course of time, and yet we still hold true to it, as if at some point, it’s gonna trickle down to the right people. And invariably it seems like greed, human frailty, all of the things that make us struggle as human beings, those things get in the way of “doing the right thing” or America being the idea…actualizing itself to the best of what it could be.

HILOBROW: We welcome Mags to the group!

NOCENTI: Hi Mags! We’re talking about Reaganomics and trickle-down theory and how nothing ever trickles down. It’s weird that these days it feels like presidential politics is more about a cult… It goes way back in our history of course, the P. T. Barnums and the snakeoil salesmen, the idea that we now have a cult running for office.

HILOBROW: Certainly in a book like Marilyn Manor, Mags, you were starting to get into some of that strange, occult history of the presidency… Why is it that presidents and other public figures like them seem to lend themselves to outlandish tales and weird speculation? You were first known for a comic where Andrew Jackson was in SPACE [laughs] and then did one about secret passages underneath the White House; is it that we have a sense that everything we see in the persona of a president is this kind of performance…?

VISAGGIO: I think we just mythologize, I think we have this tendency, and I don’t think it’s particular to the United States, but we mythologize our leaders in this very strange way — we’ve been doing it for ages and ages; you mentioned Andrew Jackson in Space; Andrew Jackson has all this mythology around him, the whole thing was “He’s the new George Washington, he’s the guy who’s bringing democracy,” and there’s no truth to any of it. We want to view our leaders as capital-G Good people, who are on capital-O Our side, and that’s way easier to deal with than the truth, which has only gotten more pronounced in recent years, that they’re on their own side, they’re not looking out for us; even the good presidents weren’t looking out for us.

RUSSELL: Michel Foucault once said, writing in the 1970s, that the difference between the old totalitarians of the ’30s and ’40s like Stalin and Hitler, and the new totalitarians that would come in the next generation was that the old totalitarians sort of posed themselves as these supermen, these aspirational figures who could do no wrong and were infallible, and the next wave of totalitarians would be what he called Ubu-ism, which is like the opposite, where these people become lionized or they gain power because they show us the worst traits of ourselves and allow us to sort of revel in it, they give us permission to be our absolute worst selves. And I think he was foreseeing the present moment, because this is really the dark side of populism, which is different from democracy, because it’s not what we want, policy-wise, it’s more like there’s somebody who’s finally allowing us to be the person we’ve been pretending not to be. I think this was so intoxicating for so many people who had felt like they couldn’t make racist jokes at work anymore, or couldn’t engage in sexual harassment at the workplace, and then someone like Trump comes along and is able to get away with all this stuff, and is able to talk about, y’know, Mexicans being rapists and murderers and saying all the stuff they’ve been thinking themselves but felt like they couldn’t say anymore. For a lot of these people it was like putting on a pair of pants that fit for the first time in 30 years. I think that kind of explains the wave of, sort-of, cult-like populism that buoys someone like Trump, and it’s very dangerous because it’s hard to come up with an argument that counters that feeling of somebody realizing, “this guy’s as racist as I am,” or “this guy allows me to be the person I was in the ’80s.”

VISAGGIO: I think it goes a little deeper than that too, because there’s a lot of racist politicians who are happy to give that permission who don’t have the same cult around them… I think a lot about the power of the Taylor Swift endorsement. It’s also the cult of celebrity, and the way that form eclipses substance in the cult of celebrity in our media ecosystem. Buoyed by decades of 24-hour news just trying to find something to keep the story going. We made this diagnosis years ago, right in the aftermath of 2016, it was like, the news media gave Trump all this free fucking advertising, because he’s such a compelling story, and such an entertaining figure — and he is, he’s an entertainer, that’s how he became president. And we just have ceded such an outsize amount of influence over our society to entertainment. Which is funny for me to say, as someone who works in entertainment [laughs], for all of us who work in entertainment. But that feels in a lot of ways like it’s all we’ve got left. And we’ve even seen a cult aspect of that seeping in in the way that fandoms have become these weird intense cults; and so, Trump is a fandom with political power.

BARNES: It almost feels too, like with Trump, it’s not just about the racism thing and the comfortability thing, it seems like he almost slams the door on any idea of decorum, any of the elitism of being a politician or being a president. It used to be a thing where you would have politicians go around and have a beer with someone, and sit down, and “he’s just a regular guy who’s gonna roll up his sleeves and work for us,” but he’s gonna go back to a place where he’s gonna be sitting on a throne and he’s gonna make decisions for me. But with Trump it feels like he’s just a regular guy that doesn’t care about anything; he’s “just like us” in the sense that all of that is BS, all the elitism of the White House, and the Capitol, any of the things that go with the ideal of being a politician, he’s gonna knock all of that down, he’s gonna be just like me, he’s gonna be the guy that comes in and tells it like it is, and — the pro-wrestling kind of thinking. He’s just a regular guy. And I don’t think anything is farther from the truth, but I think a lot of the people who support him feel like he’s closer to them and cares about what they care about, when I don’t think he cares about any of that.

HILOBROW: The irony here of course is that comics is what could be called a populist medium; it remains relatively affordable, it’s traditionally in reach of a lot of people, and it deals in shorthand shall we say, sometimes simplifications, but also direct articulation of values in terms that can be aspirational. At the same time that this country is increasingly moving from the model of a constituency to the model of mobs, ordinary people can be where our salvation lies, if I may be so melodramatic. And most compelling in a book like Killadelphia, Rodney, are the ordinary people, the SeeSaws — I mean obviously he’s not ordinary anymore because he’s got mystical powers but, you know, people whose roots are in the neighborhood. And Julio, certainly in your stories the heroes are ordinary people who, yes, sometimes find themselves in extraordinary situations either with powers or ghostly [benefactors] etc., but it really is a story of… the people who would have been the crowd scene in old comics become the stars. To what extent do you feel there is a way out, or a better way, in doing these stories that center the individual and the ordinary person?

ANTA: It’s tough, because… I was asked in a recent podcast how am I feeling about the upcoming election. And I think like most people, I don’t feel great about it; I think it’s very clear that we have one option that is much better than the other option, but from my perspective it’s still not a great option; it’s still an option that is more of the same, more of these US imperialistic policies that dominate the entire world, and us here at home. But what I said, and I think it goes to your question, is that if I have faith in anything, it’s in young people that are coming up now, that are becoming radicalized by what they’re seeing, and I mean “radicalized” in a positive way, in a way that opens the curtains and helps them see the ways that our policies internationally impact us here as well, and take away from us; even if you don’t care about the genocide, even if you don’t care about what is happening all over the world, how it takes away from us here at home. For me, my hope is always in the people, my hope is in communities coming together, and not in any political party, or any president.

I mentioned this earlier, before Rodney and Mags came on, but being in my college years during the Obama presidency really opened my eyes to that, where, y’know, I voted very proudly for Obama, and then saw him become the president that deported the most people in the history of the United States. That’s an issue that I care about deeply, and there’s plenty of other issues that other people care about deeply that he also had a negative impact [on], despite being this great hope for liberalism and progressivism. And it helped me realize that we can’t build up these kings in our heads, these politicians that are gonna solve everything, because that doesn’t exist, because we’re all, none of us are perfect, but most importantly, whether it’s Trump, or Kamala or Obama or whomever, they’re all paid for by the same people, by the same corporations, by the same donors who buy off both sides, and have the expectation that their [interests] are going to be prioritized. So for me, I center regular people in my stories because that’s who I truly believe is gonna change things if things truly do change and don’t just continue to go downhill.

VISAGGIO: On that note I wonder to what degree superhero comics have kind of primed our society, especially the Marvel movies.

NOCENTI: The idea that comics sort of started as this underground, voice of the people, and at this point you have a megacorporation that’s putting out comics, so comics, even though they’re written by individuals, are they the voice of the people if they’re being put out by these megacorporations? I write superheroes, I love writing superheroes, but I’m very aware of the escalation narrative, going back to the ’80s when I went into my Daredevil editor’s office and said, “Couldn’t I just do one issue where Daredevil peace-negotiates instead of escalating into a fight?” and he said, “Get outta here.” We’re now at almost 90 years of this power fantasy, escalation narrative, and they have reached the top of the culture if you want to call it the top, with these movies that I feel like even the fans are getting tired of to a certain degree.

RUSSELL: I think one of the reasons why there is dissatisfaction in American democracy is because we’ve always been allowed to challenge politics but we’ve never really been allowed to challenge ideology. In that we can advocate for specific candidates, we can advocate for specific policies; we can’t advocate for a different system. And a lot of the attendant horrors of capitalism, as Julio is pointing out, or imperialism, are just sort of baked into the political system, and no one candidate, or no one election is gonna change that. So we’re locked in, and I think that the violence narrative, or the just-trust-a-few-white-billionaires-and-they’ll-fix-everything narrative that is usually the underlying theme in superhero comics is kind of an expression of that. That, well, we can change minor things on the streets, but overall this is the way the power structure works and you’ve gotta be on board because we don’t have anything else.

VISAGGIO: Batman fights the Joker but he never fights Jim Gordon.

RUSSELL: Right. And I don’t know if it will take a calamity for us to be able to get to the point where we can sort of discard the entire system and come up with something new, or if it’s the sort of thing that hopefully we could do gradually through winning democratic elections and pushing the Overton window, but I think that’s why so many people are disillusioned with American democracy, and to a degree with superhero comics, because it becomes like professional wrestling.

VISAGGIO: I remember reading, some years ago, a study on “Is America an Oligarchy?” and they analyzed, on just a slew of issues, where you have things that corporations and billionaires want versus the things that poll after poll after poll would show that just majorities of people want, but this one always wins. I think the structure of how this all functions is so molded into our conception of what this country is, that to change it is un-American. You have some people who treat the Constitution like it’s the Bible, and then you have people who, you can’t even question the underlying structures of our economies of wealth and resource distribution without people flinging nonsense insults at you. I take some solace in that more and more of us are disillusioned with it, but who knows if that’s going to accomplish anything, it feels sometimes like we’re the one country where we can’t change anything.

NOCENTI: What Mags said earlier about media — like that moment when suddenly I noticed that Kamala’s ads were green. What is this green color? Some celebrity singer labeled her “Brat” and “Brat” was green. Why is Kamala co-opting this green Brat thing …and then it just sweeps through people’s consciousness and vanishes. I watched one of the singer’s videos and it seemed to be that Brat means you can mess up your life with impunity, which kind of feels more like Trump. The whole thing gets confused into a lot of memes, washes over us, and then everyone’s like, “Next!”

And for me, as someone who has lived in Haiti, that moment when suddenly they were talking about Haitians eating cats, and JD Vance literally said it doesn’t matter if it’s true or not, I’m just gonna keep saying it, because his followers repeat it, believe in it… as if you can label an entire country that way, which for Haiti goes back to Trump calling it a “shithole.” It’s outrageous that these things even get any credence, and that it can become a major talking point in a presidential election. Without looking at the extraordinary complexity of this little town of Springfield, where hardworking people went because they heard there were jobs. But if Vance repeats it often enough, it feeds into some racist mentality that, like Julio was saying, impacts our borders, and who comes into America. Every move you make has repercussions that are invisible at first.

ANTA: To your point about speaking these lies with impunity, I think the worst part is that it has impacts on real people. There’s all these reports from Springfield of bomb threats being called in to schools and schools being closed, and all of these threats and real-world violence that people are now subjected to. Just because some politicians wanted to drive the narrative, and shift the narrative to “immigrants eating dogs” because he happened to be losing a debate on national TV. And all it takes is that to now end up with weeks of this coverage and this story, and to [Mags’] point about the media needing to feed the story and keep it going, we just end up in this cycle, and there’s no way to talk about the actual issues.

NOCENTI: JD Vance says “crazy cat lady,” and then Taylor Swift uses it as a moment to say “I’m a crazy cat lady who’s backing Harris,” and these are these weird sparkly top moments that control the narrative. Then you hear voters saying “I don’t know who Kamala Harris is, I don’t know what she stands for, but we know Trump is a good businessman.” And no matter how many news reports show how many people he’s bankrupted, how many bills he doesn’t pay, they still perceive him as a good businessman who would be better for the economy. What Mark said early on, when you said something about it’s not a time for subtlety, it’s a time for urgency, that got me thinking, because how do you break through the white noise?

HILOBROW: There’s almost a flip of reality and fantasy. It says something about the pass that we’ve reached that I can go to fiction for more reliable reality and certainly for an emotional and philosophical truthfulness. Toward the end of your series HOME, Julio, when a very passing power fantasy is realized for some of the [young people], and then one of the adults is like “what the hell are you doing, you’re drawing attention to us,” it’s like the entire danger we’re under is not gonna be solved by a few expressions of force… I thought that that was a very refreshing, and in a strange way reassuring splash of reality; it’s almost like I can get more truth from a comic book in this case than I can get from the news media. Do y’all think of yourselves as journalists of a sort, or being in that kind of position? Sometimes Annie, your protagonists are journalists, like in The Seeds…

NOCENTI: Denny O’Neill and I used to talk about this, how we were wannabe journalists. Denny is the one who showed me his Batman stories where he said, Look, you’re a frustrated journalist, just fold it into your comics. And that became kinda my style. The Seeds is really about problems within journalism. Journalism is a dying industry because of money. People aren’t putting money into good journalism anymore. I used to get anywhere from a dollar to five dollars a word to write a journalistic piece. Now, people want to pay you $50 a story. So there’s a problem going down to the roots; people understand that you can’t make a living as a journalist. So how are we getting our information if there’s no journalists?

VISAGGIO: Well it used to be Twitter and then that went away. Not that that was particularly more reliable. But at least we had the channel. And Twitter has become X and as bad as Twitter could be, X is just every shitty thing of it given the center stage.

NOCENTI: Yeah, the model of Twitter originally to be like a decentralized place where you could hear everyone’s voice, that did not last long.

RUSSELL: I think we entered a very dangerous period when billionaires realized that they not only wanted to own the media, they wanted to control the media. They wanted it not only as a method to turn profits but also as a means to supply the narrative that was useful to them.

VISAGGIO: I’m not sure that’s ever not been true.

RUSSELL: There’s always been yellow journalism, but I think what’s especially dangerous now…

VISAGGIO: I’m not even talking about yellow journalism, but if you go back to the birth of the American news media, it was all party organs, and billionaires promoting their interests, that’s always been the case.

NOCENTI: When I was going to Columbia University, to the School of International Affairs, there was this company Gannett, and Gannett was gobbling up media, and I remember taking a journalism class, and they handed me Ed Herman and Noam Chomsky’s Manufacturing Consent. At the time there was this Gannett News Channel 1 or whatever, and they had just made a deal with schools — this is back when TVs were expensive [laughs] — that they would bring a TV set into every classroom as long as they would also run the M&Ms ads, and they brought commercials right into the classroom in order to get the TV itself. And then Ed Herman and Noam Chomsky famously said, the more media gobbles each other up and is owned by the Murdochs and then Roger Ailes and the rise of FOX news, that’s when it really, the idea of truth just went out the window.

VISAGGIO: I think that the same way we mythologize our leaders, I think to a degree we’ve also mythologized journalism, which is a fairly recent development in human civilization; this idea that there’s this channel of reliable objective media, when I’m not sure that’s ever really existed…

RUSSELL: It’s definitely different now though —

VISAGGIO: I don’t know that it is, it’s different in form, but I don’t know if it’s different in the overall substance.

RUSSELL: We run the risk of under-engaging [with] the danger we’re currently in, because I think what’s different now is that social media has allowed the sort of industrialization of bullshit in a way that’s never been possible when people were just publishing newspapers, and you could choose between three or four —

VISAGGIO: That’s just a question of scale, though.

RUSSELL: Yeah, that’s important; this is what determines elections, this is what determines realities. And the fact that you had, a few years ago, what was a relatively neutral source where people could promote their opinions and their agendas, albeit owned by a billionaire, and now it’s basically to service far-right ideologies and conspiracy theories, and industrialize disinformation, is an incredibly dangerous, and unique danger that’s not really comparable to yellow journalism or for-profit journalism. I think those things were bad, and they’ve always been present, but I think we’re at a uniquely dangerous moment now, just because of the role that social media plays in our media consumption.

HILOBROW: There used to be prestige in the idea of “objectivity”; there were certain values that were more or less consensually agreed on in this society that even billionaires would adhere to because there was a certain cachet in saying, we’ve got this high standard of journalism. The further you go back in time, the more there were — however few and far between — major scandals that were [uncovered] by journalists being brave and the moneyed people who owned the journalists letting them get away with it — like Watergate, like the Pentagon Papers —

VISAGGIO: I just can’t help but think about the media’s role in manufacturing Red Scares, in manufacturing the Satanic panic and perpetuating these crises that didn’t even really exist. The news media has always been in the service of the ruling ideology, whatever that is.

BARNES: I think, to what Mark is saying though, that idea about the Red Scares and all of that, now that reaches the ears of the people who didn’t listen at one point. I think social media and all of those things gets it to an ear that at one point wasn’t paying attention and now is influenced in a way that I don’t know if it was influenced back in the ’60s or the ’70s.

VISAGGIO: You mean back when there was only three news sources that everybody watched —

BARNES: —Yes, exactly—

VISAGGIO: —all saying the same thing, so that if everybody agreed, then that was reality. That’s the part where I just kind of lose the thread. We can talk about Cronkite and we can talk about Murrow and we can talk about objectivity, but when there were only three sources for media and they were all saying the same thing it didn’t matter if what they were saying was true.

BARNES: I think social media personalizes it in a way and is geared to reach the ear not in a bulk-rate way, that it’s manufactured and PR’d to get to every person, to specify the message to virtually everyone. People before that I knew who didn’t give two shits about politics or anything now have an opinion about something, where there’s Trump, in a way that I don’t know if they did when it was Carter, or it was Bush. Just in a different way, and a lot more personalized.

RUSSELL: Being an old myself, I feel like the political discourse is very different now than it was when I was younger. And I’m not saying that the system of having three news networks all invested in the preservation of the status quo is good, but it was different than what it is now, where everyone’s allowed to silo themselves in their own reality and never come into contact.

BARNES: That’s what I’m saying, yes.

HILOBROW: There’s an irony in that, the more concentrated media was, the fewer options there were, I think it gave rise to a more robust underground and a more defined alternative, than there is now; now we’re not all just silo’d but we are each our own “expert,” and what that fosters is people saying “it could be this, or it could be that”; there’s no baseline for reality.

NOCENTI: I just keep thinking about what Mark said early about comics and it’s a time for urgency, not subtlety. I don’t know why it stuck with me but I feel like the art of comics is the art of subtlety, in a weird way. You’re putting themes in your comics, then you kick a lot of sand over them so that they will be palatable as entertainment, as opposed to let’s just tear that down and do a manifesto. So I keep thinking about that in terms of how it impacts the comics form, and how it will impact the comics form.

HILOBROW: It seems to me that different problems call for different reactions, and it’s kind of like when absurdity becomes authority, then satire becomes duty — I wouldn’t consider everybody here to be a satirist, but in books like Mags’, Mark’s and Annie’s it’s probably more on the surface in terms of actual out-and-out comedy, though certainly humor and absurdity work their way into Rodney’s and Julio’s stuff as well — to what extent do you think that court-jester function so to speak is one good strategy to work in these times?

NOCENTI: A film just leaped into my mind, I remember when Election came out, it was a comedy by Alexander Payne and Jim Taylor. They had the “Hillary Clinton” character, and the “Reagan” character, and it was a full-on satire, a brilliant satire I thought, and I remember the reviews at the time were like people saying, “Yeah, what happened to satire?” In the ’60s and ’70s movies used satire all the time, like the films of Robert Downey Sr., like yeah, what happened to satire in film, and the film “Election” was refreshing. So I think to your, whatever was the phrase that you said before, Adam?

HILOBROW: Oh, “when absurdity becomes authority, then satire becomes duty”; I was paraphrasing a character from Killadelphia named Thomas Jefferson [laugher]

NOCENTI: That’s perfect. I guess that, if we want to point an arrow towards where comics could head, if you’re considering comics as any part of the rescue mission of our souls.

HILOBROW: Any final thoughts — or manifestos — that people would like to give? Generally I might ask, how do you as individuals see your place and your role, and how what you do as artists interacts with yourselves as political beings?

VISAGGIO: I think of myself as a punk musician. To the degree that I’m not overtly trying to make political statements but I’m just trying to express the things that I understand about life and the world and all the ways that it’s super fucked up, and I know that it’s very hard to separate all of that from politics. But I think of myself as being on the more raw emotional side of it and not on the articulating capital-T Thoughts, just “here’s my anger and my sadness about these things, for you to share.”

ANTA: I think for me at the top level it’s just about trying to tell the truth, and writing about my interests and what I’m passionate about. So, at the moment I’m passionate about the way that rightwing extremism gets into teenagers and influences them in really negative ways; that’s how we got my new Blue Beetle graphic novel. And then it’s about figuring out how to make that into a sci-fi superhero story. So at the end of the day I think it’s just about writing for yourself, obviously with an eye for a reader, but just being true to yourself, and true to what you believe, and just trying to tell a story that in a way educates and entertains.

RUSSELL: I think the most primal, powerful…power humans have ever come up with is conversation. And I feel like that’s all I really aspire to do with writing, is to talk about the things that I think are going to get us all killed, or the things I find hope in, and hopefully spark some sort of conversation. And hopefully the conversation turns into something; I can’t, there’s very little I can personally do but hopefully conversation takes on a life of its own and becomes at some point action.

BARNES: It’s similar for me too; I mean, Killadelphia was born out of a conversation with my daughter about critical race theory. She was talking about history in books that she wasn’t allowed to read. And she asked me my opinion about the Founding Fathers, and that was the beginning of writing this story. So, it’s always been about truth; you know my mother was a schoolteacher and I grew up reading a bunch of stuff from the Black Panthers, from movements in the ’70s and those things, and those are still kind of in me, that fighter thing is still in me, and I use comics as a way of expression.

NOCENTI: What you’re all saying, I agree with all of it, and I think what Mags said about working from your anger and your sadness, it’s… I started working on The Seeds when the bees were leaving. There were all these news stories about “the bees are leaving, why are the bees leaving,” and in my own little world I started creating habitats for bees, I let flowers grow rather than grass; and then found out that in China they were making robotic bees, because the bees were leaving, so we’re gonna need somebody to pollinate flower to flower. So out of fear, anger, and sorrow for bees, you can start building a story; so for any young writers out there reading this, it’s a good method, to just accumulate your rage and sadness and fear and fold it into something that has meaning and build a story from there.

MORE POSTS by ADAM McGOVERN: OFF-TOPIC (2019–2024 monthly) | textshow (2018 quarterly) | PANEL ZERO (comics-related Q&As, 2018 monthly) | THIS: (2016–2017 weekly) | PEOPLE YOU MEET IN HELL, a 5-part series about characters in McGovern’s and Paolo Leandri’s comic Nightworld | Two IDORU JONES comics by McGovern and Paolo Leandri | BOWIEOLOGY: Celebrating 50 years of Bowie | ODD ABSURDUM: How Felix invented the 21st century self | KOJAK YOUR ENTHUSIASM: FAWLTY TOWERS | KICK YOUR ENTHUSIASM: JACKIE McGEE | NERD YOUR ENTHUSIASM: JOAN SEMMEL | SWERVE YOUR ENTHUSIASM: INTRO and THE LEON SUITES | FIVE-O YOUR ENTHUSIASM: JULIA | FERB YOUR ENTHUSIASM: KIMBA THE WHITE LION | CARBONA YOUR ENTHUSIASM: WASHINGTON BULLETS | KLAATU YOU: SILENT RUNNING | CONVOY YOUR ENTHUSIASM: QUINTET | TUBE YOUR ENTHUSIASM: HIGHWAY PATROL | #SQUADGOALS: KAMANDI’S FAMILY | QUIRK YOUR ENTHUSIASM: LUCKY NUMBER | CROM YOUR ENTHUSIASM: JIREL OF JOIRY | KERN YOUR ENTHUSIASM: Data 70 | HERC YOUR ENTHUSIASM: “Freedom” | KIRK YOUR ENTHUSIASM: Captain Camelot | KIRB YOUR ENTHUSIASM: Full Fathom Five | A 5-part series on Jack Kirby’s Fourth World mythos | Reviews of Annie Nocenti’s comics Katana, Catwoman, Klarion, and Green Arrow | The curated series FANCHILD | To see all of Adam’s posts, including HiLo Hero items on Lilli Carré, Judy Garland, Wally Wood, and others: CLICK HERE