FIRST TIME AS COMEDY (15)

By:

October 21, 2024

Some years ago, HILOBROW friend Greg Rowland pointed out that the 1990 movie Dances With Wolves ought to be regarded as a sentimental remake of the 1970 revisionist Western Little Big Man. The series FIRST TIME AS COMEDY will offer additional examples of this recursive (and often, though not always middlebrow) syndrome.

FIRST TIME AS COMEDY: SUPERDUPERMAN vs. WATCHMEN | WILD IN THE STREETS vs. PREZ | EMIL AND THE DETECTIVES vs. M | THE SAVAGE GENTLEMAN vs. DOC SAVAGE | GULLIVAR JONES vs. JOHN CARTER | THE PHONOGRAPHIC APARTMENT vs. HAL | HIGH RISE vs. OATH OF FEALTY | JOHNNY FEDORA vs. JAMES BOND | MA PARKER vs. MA BARKER | DARK STAR vs. ALIEN | SHOCK TREATMENT vs. THE TRUMAN SHOW | JOHNNY BRAVO vs. ROCK STAR | THE FUTUROLOGICAL CONGRESS vs. THE MATRIX | CAVEMAN vs. SASQUATCH SUNSET | LITTLE BIG MAN vs. DANCES WITH WOLVES | THE LAST BLACK MAN IN SAN FRANCISCO vs. BE KIND REWIND | LEN DEIGHTON vs. LEN DEIGHTON.

As I note in the introduction to each installment in the series, it was this particular match-up that originally sparked the whole first-time-as-comedy notion. (Although Greg Rowland now tells me that he doesn’t recall making that comparison.) But I’ve dragged my feet about writing this installment… because I didn’t want to rewatch Dances with Wolves. However! Earlier this year my semiotics consultancy was tasked, by a French action/adventure videogame company, with analyzing a couple dozen Westerns… including Dances with Wolves and Little Big Man. *Sigh.* Non duco, ducor.

Dances with Wolves (1990) is an epic Western starring, directed, and produced by Kevin Costner. It was the fourth-highest-grossing film of 1990, and it won seven Academy Awards — including Best Picture, Best Director for Costner (in his feature directorial debut), Best Adapted Screenplay, Best Film Editing, and Best Cinematography. The movie is credited as a leading influence for the revitalization of the moribund Western genre in Hollywood; before 1990, no Western had won an Oscar for Best Picture since 1931’s Cimarron.

In 1863, the Union Army’s 1st Lieutenant John J. Dunbar, a self-sacrificing war hero, requests a transfer to the American frontier. He’s nostalgic for the wide-open West, which he fears is already vanishing. Arriving at a deserted military post on the western prairie — the movie was mostly filmed in South Dakota and Wyoming — Dunbar lives an isolated life until he encounters his Lakota Sioux neighbors. Though the tribe is at first suspicious of him, Dunbar establishes a rapport with them — and he comes to respect and appreciate them too.

Dunbar learns to speak the Lakota language (much of the movie’s dialogue is spoken in Lakota with English subtitles), and forges a romantic relationship with Stands with a Fist (Mary McDonnell), a white ethnic Sioux woman who was adopted as a girl by the tribe’s medicine man after her family was killed by the Pawnee. To help his Lakota friends defend themselves against the Pawnee — who are depicted as murderous — he supplies them with firearms stashed back at the military post (which he has abandoned too). Eventually, the tribe decides to permanently relocate from the prairie to its winter camp — because of encroaching white settlers — and Dunbar, who now dresses as a Lakota and has been adopted by the tribe, decides to accompany them. Which is when the US Cavalry finally shows up, and captures him….

Despite the gorgeous cinematography and music, and excellent performances by Graham Greene (as Kicking Bird), Rodney A. Grant (as Wind in His Hair), Floyd Westerman (as Chief Ten Bears), and Nathan Lee Chasing His Horse (as Smiles a Lot), among others, Dances with Wolves is a flawed movie. Although at the time Dances with Wolves was praised for showing a positive representation of Native Americans, today there are issues with their representation. But the central criticism, I think, that one hears of Dances with Wolves is that it is a “white savior” film… as well as an example of cultural appropriation on the part of the Dunbar character. Dunbar “goes native,” absorbing the Lakotas’ practices and worldview, and evolving into a kind of superheroic champion. One is reminded of Edgar Rice Burroughs’ Tarzan character, an English gentleman raised in the African jungle… who becomes somehow more African than the Africans themselves, a feared and awe-inspiring figure.

Twenty years after the movie’s rapturous reception at the box office and the Academy Awards, Oglala Lakota activist and actor Russell Means would remark: “Remember Lawrence of Arabia? That was Lawrence of the Plains.”

This is complicated stuff. There were earnestly progressive motives at work in the making of Dances with Wolves, to be sure; but there was something rotten at its core. “Was Dances with Wolves a subversive, revisionist Western that made clear how white people decimated the indigenous world?” demanded Roxana Hadadi in a Crooked Marquee essay a few years ago. “Or, with its depictions of valor and exceptionalism, did it live up to the same stereotypes that the historical cowboys-and-Indians genre crafted?” The answer is: Yes.

Twenty years before Costner’s Dances with Wolves, Arthur Penn directed the revisionist Western Little Big Man — adapted by Calder Willingham from Thomas Berger’s 1964 novel of the same title. Now, Berger is a brilliant novelist — a meta-fictional wizard who playfully and intelligently subverts and celebrates tropes and themes from genre fiction: everything from hard-boiled detective novels to science fiction. He’s a high-lowbrow, in other words.

The movie adaptation of Little Big Manwas never going to be able to pull off everything that Berger’s novel does. But Penn, who’d previously directed Bonnie and Clyde and Alice’s Restaurant, knows his way around American outlaw mythography. His adaptation of the novel offers us an all-American antihero, who — like Clyde Barrow (Warren Beatty) and Arlo Guthrie (Arlo Guthrie) — is a goofball and holy fool, a picaro who lives by his wits.

Despite various similarities in their story, Jack Crabb (Dustin Hoffman) is no John Dunbar; he isn’t noble, earnest, self-serious. He isn’t even particularly good. In a largely tragic story, Crabb is a comedic figure — which makes this a much better movie.

According to Crabb, an unreliable narrator — who, at the movie’s beginning, insists to his interlocutor that he is 121 years old — he and his sister survived the massacre of their parents by the Pawnee. (Note the parallel to the Stands with a Fist character, in Dances with Wolves.) His sister escaped, but Jack was raised by a Cheyenne tribe — in particular by the tribe’s kindly and wise leader, Old Lodge Skins (Chief Dan George). In 1865 — around the same time that Dances with Wolves takes place — Jack is captured by U.S. Cavalry troopers during a skirmish. Unlike John Dunbar, who when captured by U.S. Cavalry troopers insists that he is now a Lakota Sioux (cringe), Jack Crabb reveals that he is a white man and renounces his Cheyenne upbringing. In doing so, Little Big Man reveals an important truth about cultural appropriation: White people can and do adopt the trappings of other cultures, then take them off again, at will. Members of other cultures cannot. This is how privilege works in a system of institutionalized racism. The scene is played for laughs, but the message is a serious (not earnest) one; this is what I’d call engaged irony. Somehow in the twenty years between Little Big Man and Dances with Wolves, Berger and Penn’s lesson was forgotten.

Much of the rest of Little Big Man satirizes the American mythology of western expansion. The white settlers are either con artists or the dupes of con artists; or they’re religious nuts; or they’re hypocrites. The Reverend Silas Pendrake and his sexually frustrated wife, Louise, foster Jack and seek to save his soul. Later, he becomes the apprentice of a snake-oil salesman — one of the few white characters whose worldview is unprejudiced by superstition, cant, or jingoism. He briefly toys with life as a gunslinger, and is befriended by Wild Bill Hickok. Later still, Jack becomes a storekeeper and marries a Swedish immigrant; she is abducted by Cheyenne warriors. Setting out in search of her, Jack is reunited with his former tribe. Still searching for his wife, Jack joins Custer’s 7th Cavalry; Custer (portrayed by Richard Mulligan as a borderline psychotic) leads his troops in the wholesale slaughter of the Cheyenne, at which point Jack flees and rejoins Old Lodge Skins’ tribe.

Jack marries three Cheyenne women and becomes a father… at which point Custer and the 7th Cavalry attack their camp. It’s an apocalyptic scene of wanton slaughter. More picareqsque adventures transpire, and eventually Jack tricks Custer into leading his troops into a trap at the Little Bighorn. The con man has used his skills as a survivor, chameleon, and liar for a noble purpose at last: vengeance.

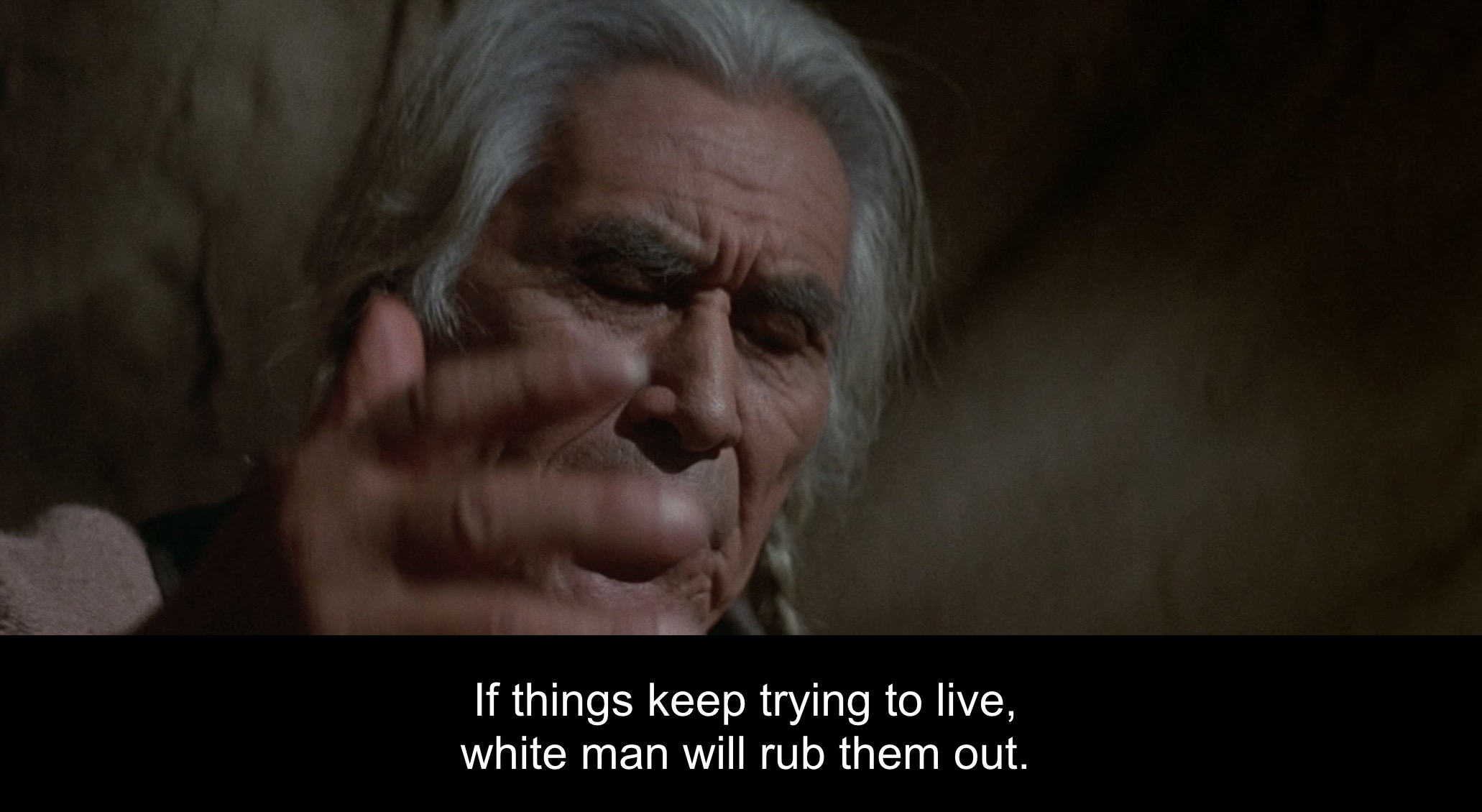

Back at the Cheyenne camp, finally, Jack accompanies Old Lodge Skins to the Indian burial ground, where the old man, dressed in full chief’s regalia, decides to end his life with dignity. When he doesn’t die, Old Lodge Skins philosophically says, “Well, sometimes the magic works. Sometimes it doesn’t.” They return to his lodge to have dinner. The movie ends, not with the triumphant spectacle of a white man turning race traitor (as in Dances with Wolves) but with Native American trickster wisdom and philosophical humor.

MORE FURSHLUGGINER THEORIES BY JOSH GLENN: SCHEMATIZING | IN CAHOOTS | JOSH’S MIDJOURNEY | POPSZTÁR SAMIZDAT | VIRUS VIGILANTE | TAKING THE MICKEY | WE ARE IRON MAN | AND WE LIVED BENEATH THE WAVES | IS IT A CHAMBER POT? | I’D LIKE TO FORCE THE WORLD TO SING | THE ARGONAUT FOLLY | THE PERFECT FLANEUR | THE TWENTIETH DAY OF JANUARY | THE REAL THING | THE YHWH VIRUS | THE SWEETEST HANGOVER | THE ORIGINAL STOOGE | BACK TO UTOPIA | FAKE AUTHENTICITY | CAMP, KITSCH & CHEESE | THE UNCLE HYPOTHESIS | MEET THE SEMIONAUTS | THE ABDUCTIVE METHOD | ORIGIN OF THE POGO | THE BLACK IRON PRISON | BLUE KRISHMA | BIG MAL LIVES | SCHMOOZITSU | YOU DOWN WITH VCP? | CALVIN PEEING MEME | DANIEL CLOWES: AGAINST GROOVY | DEBATING IN A VACUUM | PLUPERFECT PDA | SHOCKING BLOCKING.