MAN’S WORLD (15)

By:

October 17, 2024

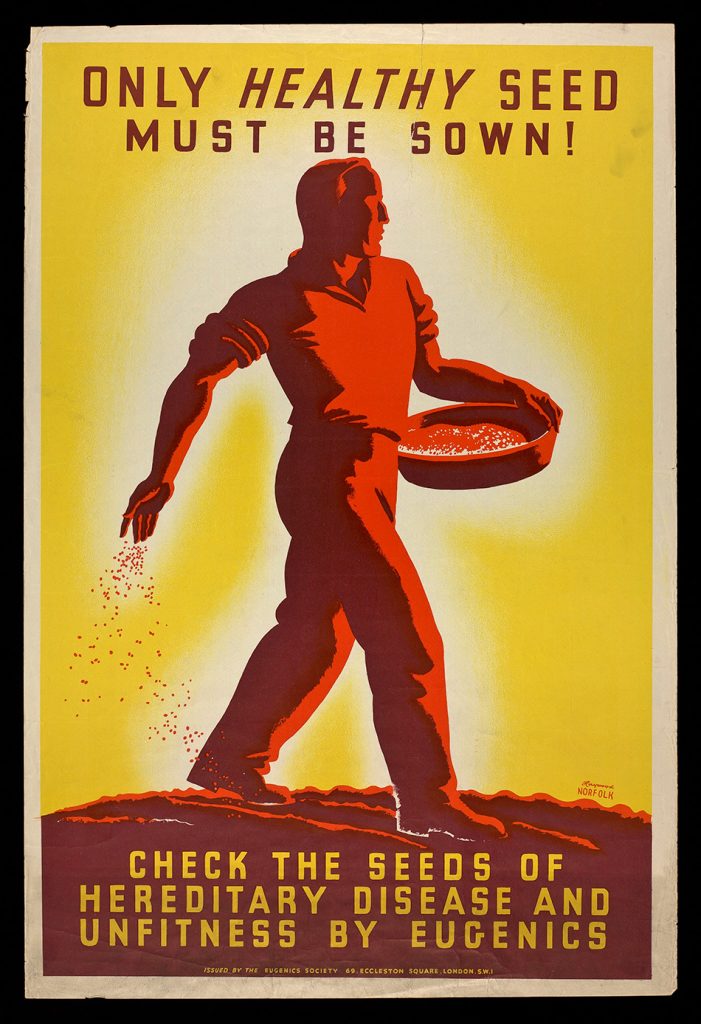

HiLoBooks is pleased to serialize Charlotte Haldane’s 1926 proto-sf novel Man’s World for HILOBROW’s readers. Written by an author married to one of the world’s most prominent eugenics advocates, this ambivalent adventure anticipates both Brave New World and The Handmaid’s Tale. When a young woman rebels against her conditioning, can she break free? Reissued in 2024 (with a new introduction by Philippa Levine) by the MIT Press’s RADIUM AGE series.

ALL INSTALLMENTS: INTRO | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25.

RECONSTRUCTION

The philosophy of art has no other aim than to bring together as far as possible into one view all that there is in the world’s memory — to make a history in which the characters shall speak for themselves, become themselves the interpreters of the history. It will regard the artists as helping to create the mind of the ages in which they live — the mind is only what it knows and worships, and the artists are the means by which the different nations and ages come to have characters of their own. W.P. KER — ON THE PHILOSOPHY OF ART.

‘Where will you sit, Nicolette?’

‘Oh, in a corner somewhere; I do dislike having the light pour into my eyes.’

‘Well, choose your own corner. Have you heard from Anna?’

‘Yes, I spoke to her to-day. She’s like a child with a marvellous new toy. She can talk of nothing but love, as if it had been invented for her special benefit.’

‘Why, aren’t you the same? Surely that is quite natural at your age.’

‘Is it? I feel rather bewildered. Raymond is a dear — but a little well, oppressive.’

‘How so?’

‘Difficult to explain. He seems so young to me. We have hardly enough to talk about. He is delicious to look at and to touch, but — is that enough, do you think?’

‘If you respect him ardently and want a child, I should think it is.’

‘Oh, he is brilliant at his job, but it is so technical, and Raymond gets bored with trying to explain physics to me. He is nice to play with, though. I have never met any one who could do everything so competently. There is not a sport at which he doesn’t excel. I never knew what swimming and dancing could be like until now. Glorious!’

‘That’s splendid. It is so important to be able to play together, you know.’

‘He’s so clever at inventing new games, too. Every one likes him.’

‘But you,’ Emmeline added in her dry way.

‘No, Emmeline, I do like him, really, very much. But do I not like him enough, or is it that I am not yet ready?’

‘How do you mean, child?’

‘There must be something not quite normal about me, I think, Emmeline. Perhaps it’s congenital, for I have been like it now for nearly two years. I love babies, I want to have them, yet as the opportunity comes nearer I shrink more from it. I don’t feel ready. I feel as if I would not be ready for years. As long as it was a lovely vision, to be realized in the distant future, my imagination leapt to meet it; I could hardly wait for the day. Now it is approaching, I recoil.’

‘Have you told your mother?’

‘Emmeline! You know I can’t tell Antonia things. I would like to, she is so sympathetic, she so wants to be consulted; but one can’t, and there it is.’

‘Well, perhaps Raymond is not the man for you.’

‘Perhaps not. And yet I like him so much; I like him physically too, to hold me in his arms, to touch and kiss me. He gives me tremendous pleasure. But something is lacking. I may have to wait; if it does not come, to renounce motherhood altogether. If only I could do something else in the meantime, just to see how things turn out.’

‘That might be arranged, but it would be a little difficult. You know the regulations in these matters are rather stringent. They have to be. Either you become a mother or you must be immunized. It is the only safeguard that must be taken for the future of the race. As soon as you abandoned it, children would be born haphazard everywhere, would be bred by the pure and the impure; it would be impossible to exercise the necessary hygienic control, and those who had no vocation for motherhood would cheat and lie, would refuse or neglect the years of preparation, the pregnancy exercises — it would simply lead to the dirty, bestial breeding of the past again. The race would be doomed.’

‘I quite agree. It would not do. And perhaps, if I am sensible, I shall find myself again. I shall be ready.’

‘Well, see how matters shape. Do not try to force yourself to this union with Raymond, and do not repress your aversions, nor suggest longings that are not really there. If necessary I will consult the council about a respite for you; only it may not be simple to find an alternative, as it was always taken for granted that you would become a mother. I often thought Antonia might not have been quite so certain.’

‘Emmeline, you are a dear! You are so helpful.’

‘When is Christopher due?’

Nicolette’s face betrayed none of her secret longing.

‘Any time, now.’

‘If I were you, I would not make any decision until you have talked the matter over with him.’

‘I don’t know if I can; he has such a lot to think of just now.’

‘Nonsense, you must.’

‘Must, nonsense.’ Nicolette smiled, for Emmeline’s briskness was wonderfully stimulating. ‘Will you come for a ride in one of the cars?’

‘No, you might break my neck.’

‘Well, what would it matter? However, Raymond shall take us. Let me call him; I assure you, you will be quite safe.’

‘Oh, I’m willing to trust Raymond.’

‘Insulting creature. Well, get ready, and meet us at the garage in an hour.’

What was the matter with Nicolette? That was the question she constantly asked herself, and that soon her perplexed relations were asking one another. Here was Raymond, beautiful, blond, upright, kind-hearted and well-intentioned, universally popular, a youth with whom any maiden might be proud to mate, and yet Nicolette, whenever she contemplated their future union and the thought of having a child by him, was thrown into a fever of restlessness and discontent. When she was with him the physical contact of his clean manliness soothed her; she welcomed and even sought his caresses, yet afterwards it seemed as if his kisses had only intensified her longing for something he could not give her.

Antonia adored Raymond, as mothers so often adore the youthful mates chosen for their daughters; from her point of view he was the perfect young man, and she sang his praises so constantly that Nicolette employed a hundred schemes in order to avoid her without hurting her feelings. Her brothers, her friends, all apparently conspired to remind her day and night of Raymond’s suitability. St. John even, when he occasionally parted the curtains of abstruse speculation that veiled his mind more and more completely as time went on, approved and encouraged. Only Emmeline, hitherto, had given Nicolette the practical comfort of a critical point of view.

Anna’s delirious happiness at the progress of her own affair only intensified Nicolette’s apparent aversion to love, mating, and child-bearing. She began to take more interest in women who were not devoted to motherhood. The Neuters, from those who performed comparatively menial tasks to such important members of their order as Emmeline, seemed wholly contented. Their interests were wide and entirely communal; they led calm and beautiful lives; their friendships were lifelong and many, and between those of all communities there was constant interchange of visits, and stimulating contact.

Again, it appeared to Nicolette that nothing could be more joyous than the existence of an Entertainer. Beauty was their cult; they were perfectly trained and fashioned to bring beauty to all the world. They were dancers, actors, singers, poets, novelists, essayists, painters, sculptors, architects — in art they found their supreme satisfaction. They smiled perpetually.

Nicolette had once gloried in the knowledge that to be a mother was to fulfil the most difficult function a woman could perform; she had thought she understood what sacrifices that career entailed, and seemed passionately willing to make them; but now she wondered often whether she might not, after all, find her vocation elsewhere.

Raymond could be summed up in two words — his own. Whatever he achieved, whatever he missed, this less than a phrase, illuminating his character by what it left unsaid, invariably came to his lips: ‘Oh, well…’ He had an unusual capacity for not noticing incidents that had a distressing effect on those more sensitive. He was not unobservant, but unaffected. His attention was concentrated into certain channels whence it rarely cared to deviate. A rather machine-like person, who performed automatically, as was expected of him. So little mattered, after all; yourself, your world, the larger but still unimportant solar system — they might have a significance, but that was not his business. A case might be made out for any hypothetical system by a competently trained philosopher. That done, what next? Raymond’s occasional thoughts on matters such as these were really a series of punctuation marks, interspersed with monosyllabic words which hardly ever formed complete sentences. ‘Oh, well…’

Raymond came from Isola, which turned out the world’s extremely valuable mediocrities according to plan. Isola had begun only a little later than Nucleus, but its aims had been entirely different from the beginning. It had been founded, not by one genius, such as Mensch, but by a group of people interested solely in maintaining the highest possible temporary average. ‘If it takes a century of apparently useless people to produce three or four genii who leave the average pretty much as they found it,’ they had said, ‘let us take our chances of genii and concentrate on raising the average. Let us formulate a few simple standards just slightly more ambitious than now obtain, but let us endeavour rigorously to abide by them.’ They had mostly been teachers and moderate politicians, these pioneers of Isola, discouraged by years spent in struggling with apparently incurable stupidity, but resolved to attempt one final experiment before their enthusiasm flickered out. Their own average age at the time was forty. They mated and had children, none of whom was destined to became an infant prodigy. Exceptional gifts were held to be a defect rather than an advantage, since over-development of one faculty appeared to inhibit the uniform expansion of the whole. All-round consistency was their aim, and they set about scientifically to obtain it.

Isola supplied the mortar which bound into a solid edifice the bricks fashioned by Mensch in Nucleus. It became famous as the source of brilliant second-raters. Imitators sprang up in several places, and when their less severely controlled efforts wavered or failed, the rate of ambition was slowed down. Very gradually, however, the rate for the average human intelligence rose. Between Isola and Nucleus there had always been friendly co-operation, and much inter-breeding.

How indeed was Raymond to know that Nicolette was behaving inappropriately, sometimes even outrageously, towards him? She felt herself that she was being unfair, but she did not understand, nor try to know, why. After their visit to the Miracle House together, Bruce had gone off again on his travels, and she had seen almost nothing of him during the remainder of her trip to Centrosome. Her training for motherhood did not include the clear interpretation of very obscure emotions. She was not at all conscious of a budding love for Bruce struggling with her established love for Christopher. Bruce was very, very nice — and a wee bit awe-inspiring; another big brother. But it was not in the least a sisterly sort of feeling that, in its desire for recognition, made things so extremely difficult for Raymond.

RADIUM AGE PROTO-SF: “Radium Age” is Josh Glenn’s name for the nascent sf genre’s c. 1900–1935 era, a period which saw the discovery of radioactivity, i.e., the revelation that matter itself is constantly in movement — a fitting metaphor for the first decades of the 20th century, during which old scientific, religious, political, and social certainties were shattered. More info here.

FICTION & POETRY PUBLISHED HERE AT HILOBROW: Original novels, song-cycles, operas, stories, poems, and comics; plus rediscovered Radium Age proto-sf novels, stories, and poems; and more. Click here.