RADIUM AGE ART (1925)

By:

September 15, 2024

A series of notes regarding proto sf-adjacent artwork created during the sf genre’s emergent Radium Age (1900–1935). Very much a work-in-progress. Curation and categorization by Josh Glenn, whose notes are rough-and-ready — and in some cases, no doubt, improperly attributed. Also see these series: RADIUM AGE TIMELINE and RADIUM AGE POETRY.

RADIUM AGE ART: 1900 | 1901 | 1902 | 1903 | 1904 | 1905 | 1906 | 1907 | 1908 | 1909 | 1910 | 1911 | 1912 | 1913 | 1914 | 1915 | 1916 | 1917 | 1918 | 1919 | 1920 | 1921 | 1922 | 1923 | 1924 | 1925 | 1926 | 1927 | 1928 | 1929 | 1930 | 1931 | 1932 | 1933 | 1934 | 1935 | THEMATIC INDEX.

In Paris, the Ministry of Commerce and Industry sponsors the International Exposition of Modern Industrial and Decorative Arts; the event gives a name to the Art Deco style.

Frida Kahlo is seriously and permanently injured when a bus in which she is riding collides with a trolleycar in Mexico City; she takes up painting while immobilized following the accident.

Freud’s The Interpretation of Dreams, which reveals a world where objects change identity along paths of resemblance and association, impelled by repressed impulses of desire and aggression, is published in French. Breton’s fascination with Freudian theory influences Miró, Picasso, and of course the Surrealists.

First Surrealist exhibition opens at the Galerie Pierre, Paris.

In 1925, Picasso begins to interlace the contours of bodies and objects, creating more sinuous versions of his Three Women of 1908. He was developing blob-like forms that fully emerged in 1927.

Franz Roh’s Nach Expressionismus – Magischer Realismus: Probleme der neuesten europäischen Malerei is published, introducing the term magic realism into cultural criticism.

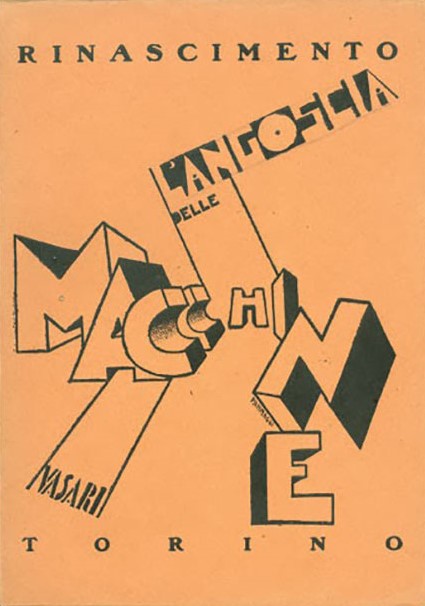

Ruggero Vasari was an Italian painter, editor and author associated with Marinetti in the evolution of Futurism before around 1930, but strongly opposed to Marinetti’s “robust” exaltation of the Machine. Vasari dramatized his opposition in L’angoscia delle macchine [“The Anguish of the Machines”] (written 1923, published 1925), a play set in a surreal near future dystopia, under the control of a master computer, where a Marinetti-like masculinist worship of the mechanical future is radically challenged by women.

Oliver Lodge, who explained his views on the aether in “Modern Views of Electricity” (1889) continued to defend those ideas well into the twentieth century (“Ether and Reality”, 1925).

Yeats’s A Vision (1925), the summa of his metaphysical thinking, sets forth what he called his “public philosophy.” It propounds an extraordinarily convoluted system that aims to integrate the human personality with the cosmos, a poetical astrology supplemented by charts and diagrams that look like figures in a geometry text.

Scopes goes on trial for violating Tennessee law that prohibits the teaching of evolution.

Hitler reorganizes Nazi Party and publishes Mein Kampf.

Also see: RADIUM AGE: 1925.

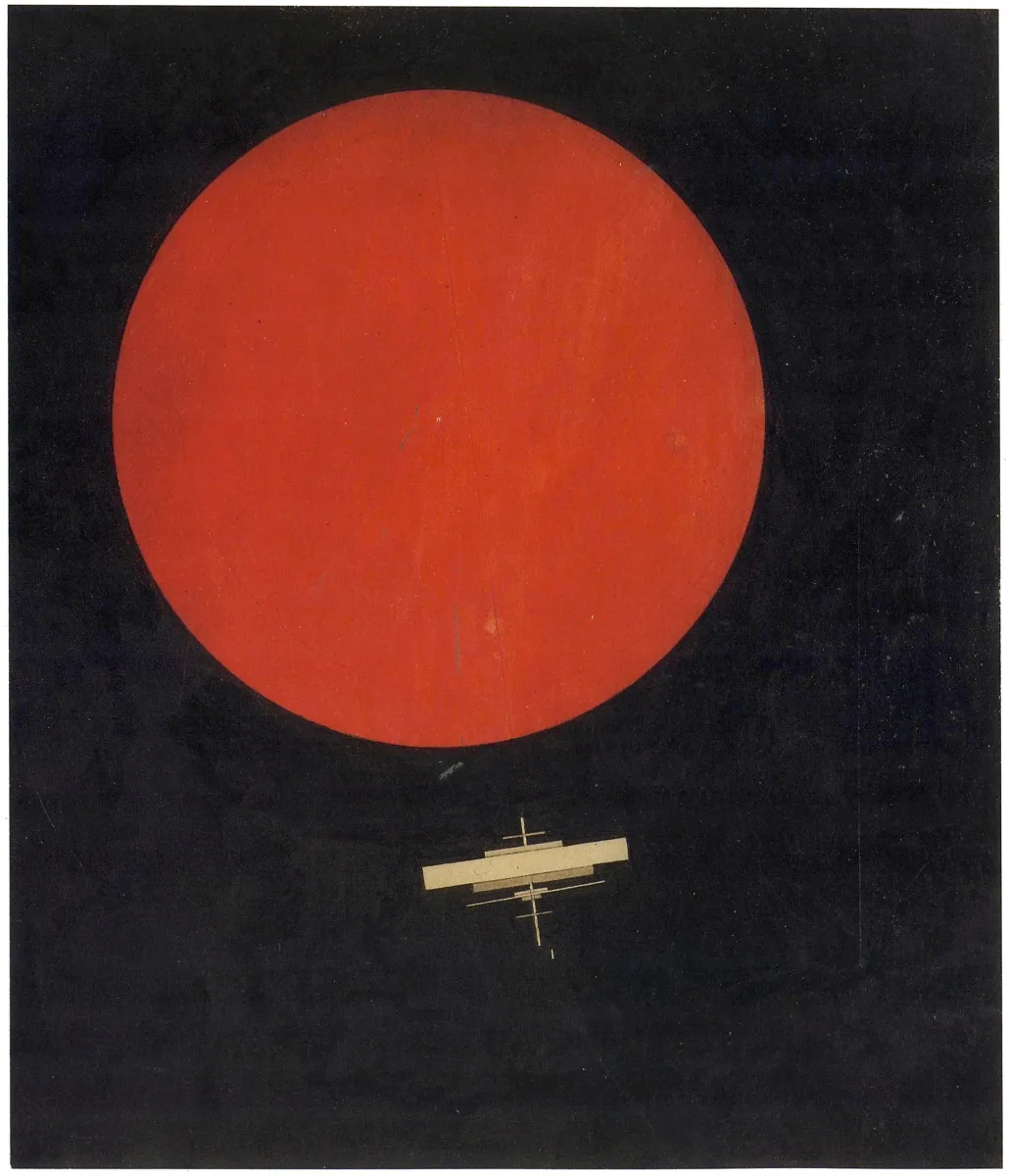

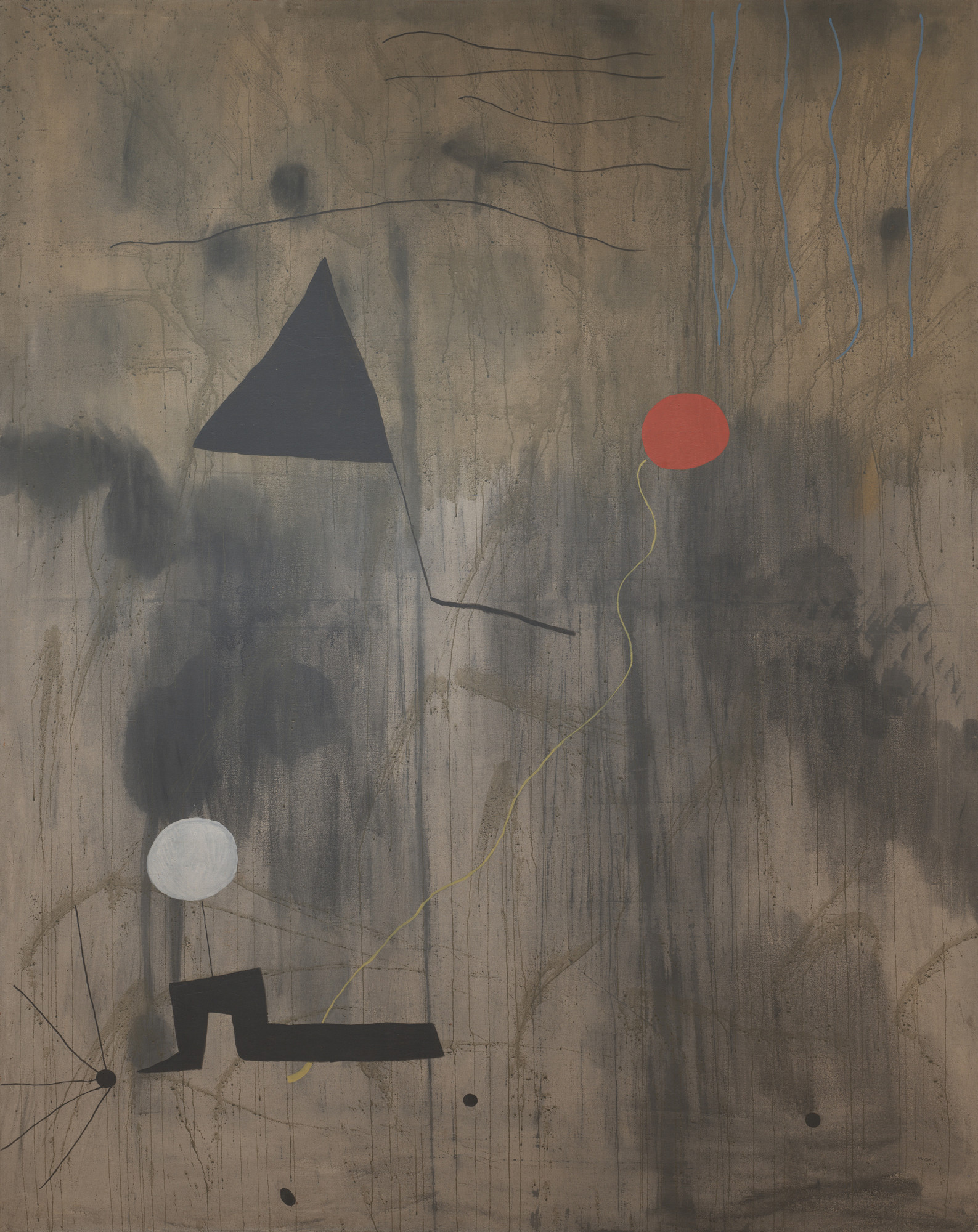

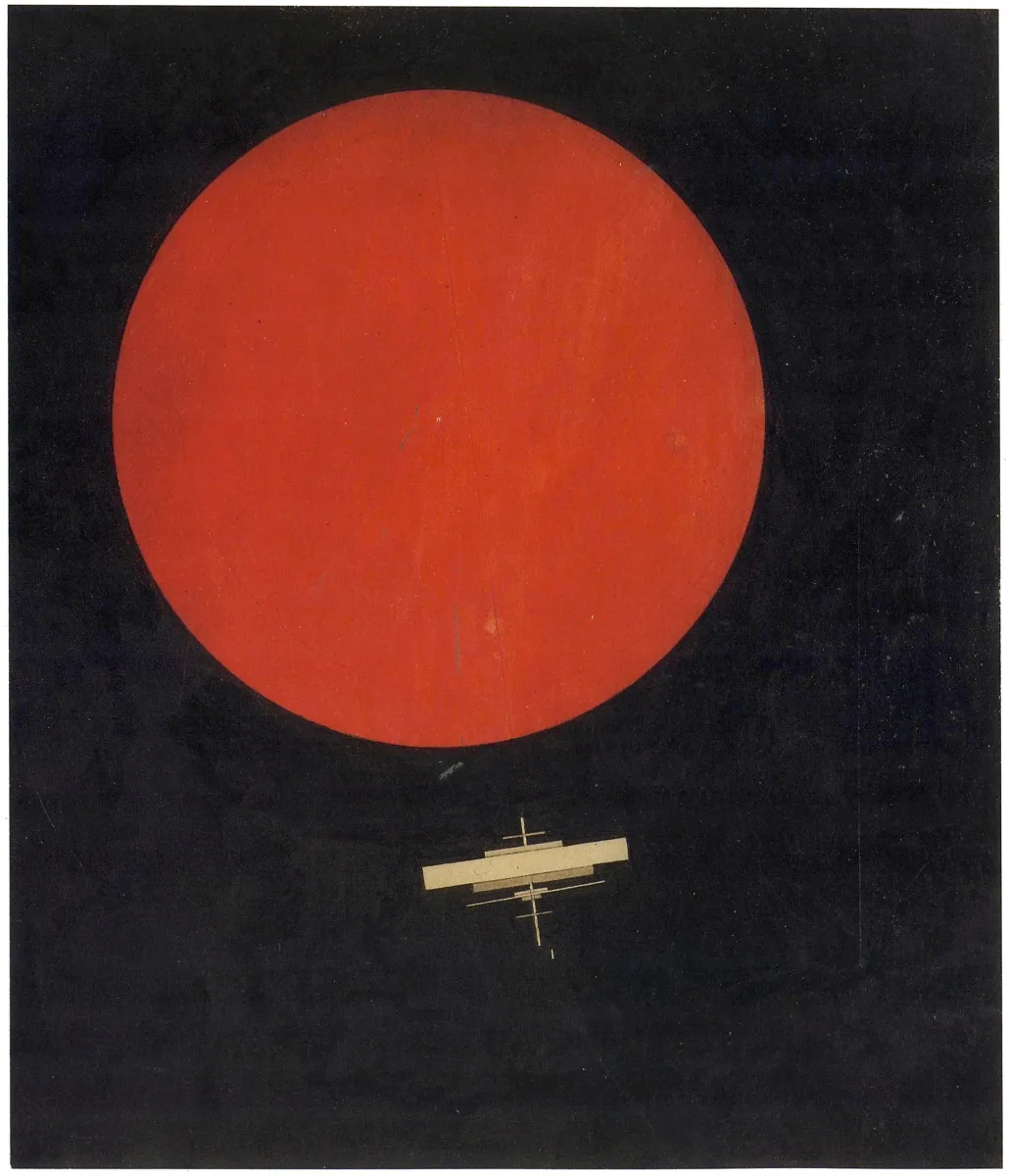

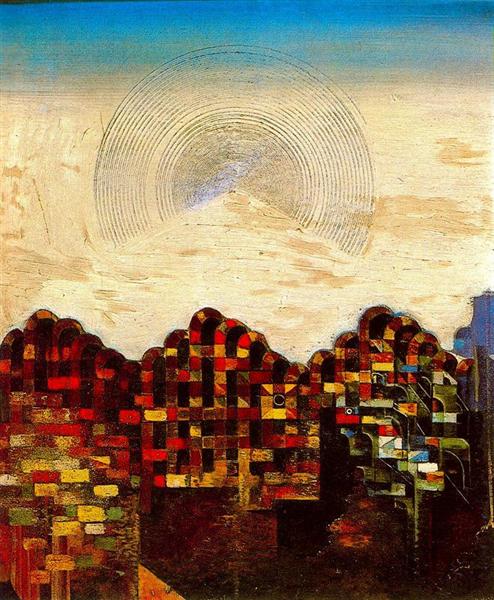

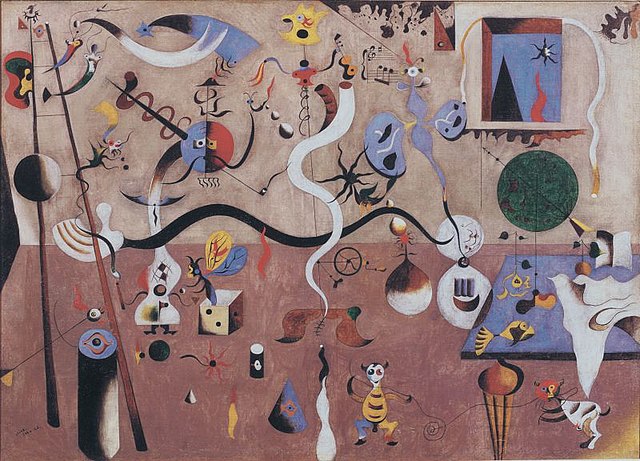

From MoMA: “In this signature work, Miró covered the ground of the oversize canvas by applying paint in an astonishing variety of ways that recall poetic chance procedures. He then added a series of pictographic signs that seem less painted than drawn, transforming the broken syntax, constellated space, and dreamlike imagery of avant-garde poetry into a radiantly imaginative and highly inventive form of painting. He would later describe this work as ‘a sort of genesis,’ and his Surrealist poet friends titled it The Birth of the World.”

According to the first Surrealist manifesto of 1924, “the real functioning of the mind” could be expressed by a “pure psychic automatism,” “the absence of any control exercised by reason.” Miro, who was influenced by Surrealist ideas, here combined chance (the way he applied the background paint) and plan (he worked out the biomorphic and geometric elements). This work deals metaphorically with artistic creation through an image of the creation of a universe.

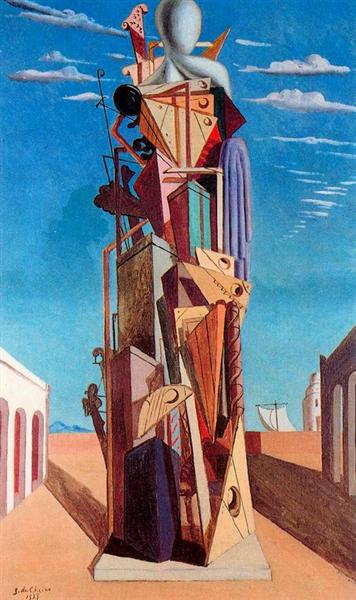

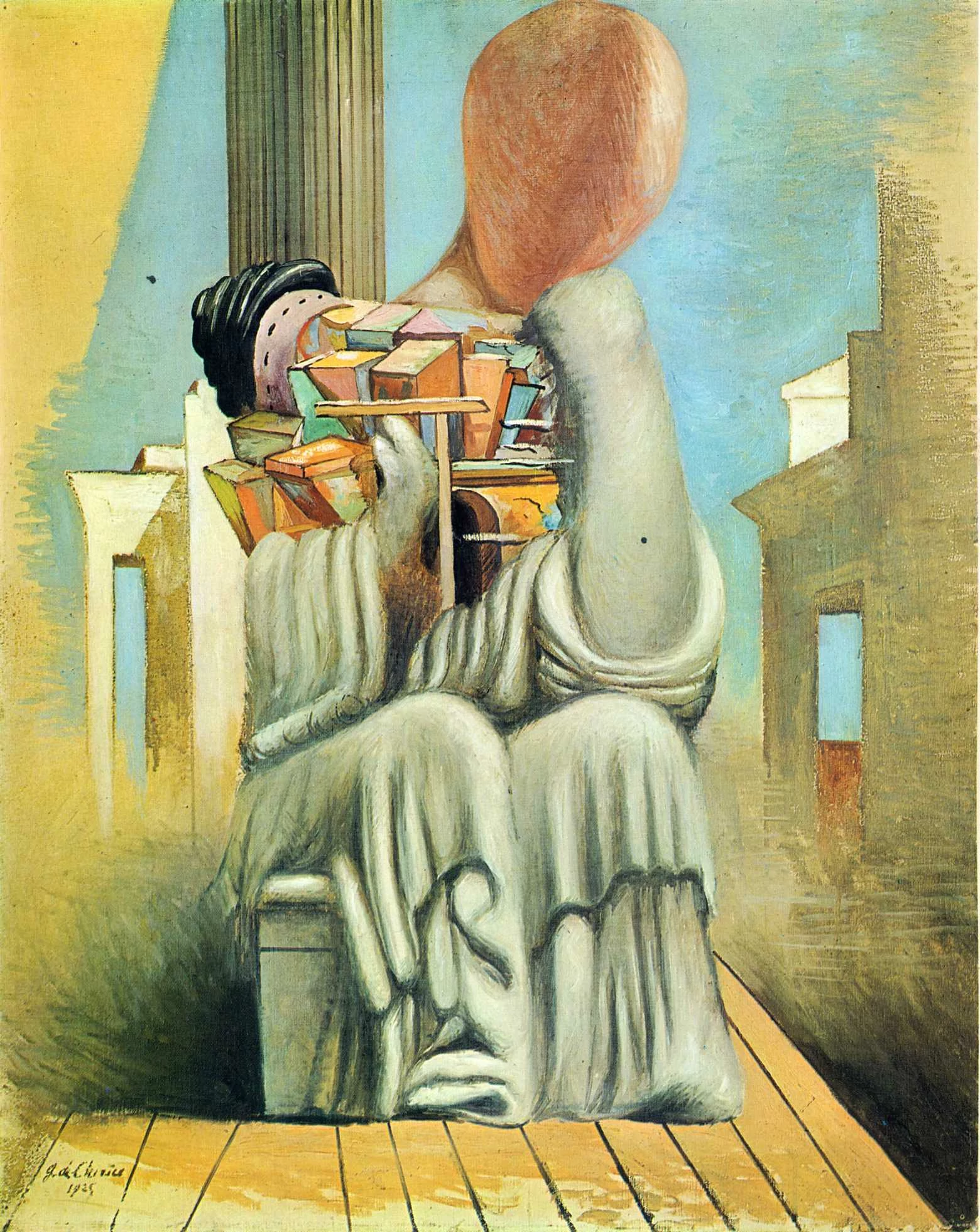

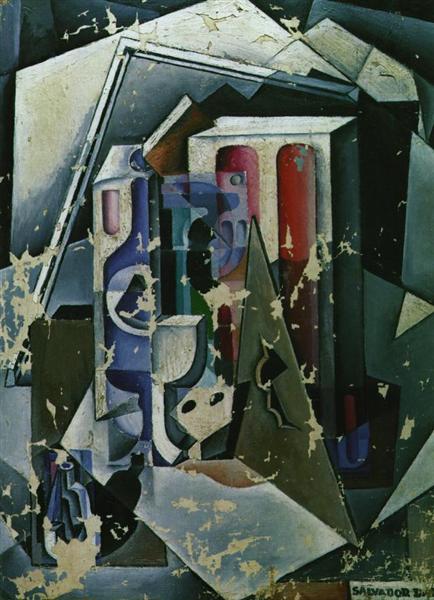

Giorgio de Chirico, 1925

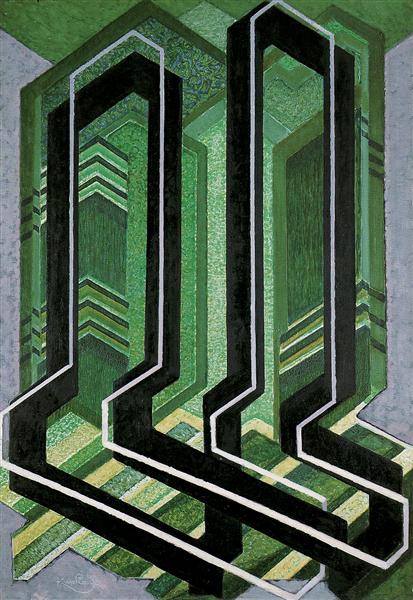

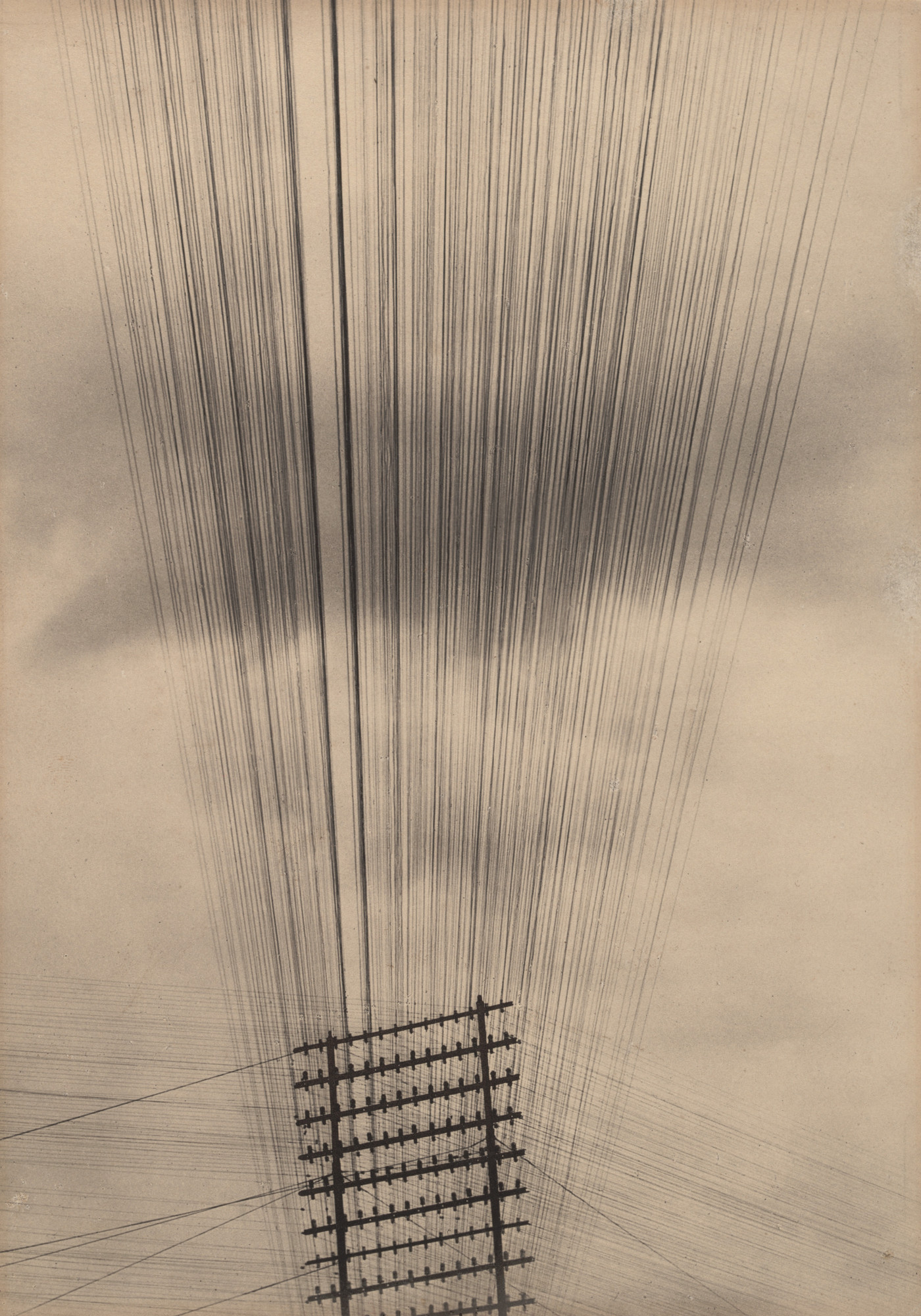

A Precisionist work.

This painting combines recognizable Catalan imagery with the surrealist style Miró had developed in Paris. The semi-figurative imagery, including that of a traditional peasant’s cap, appears to float in a translucent, dreamlike space; the carefully mapped composition is full of meaning, but deliberately defies concrete interpretation.

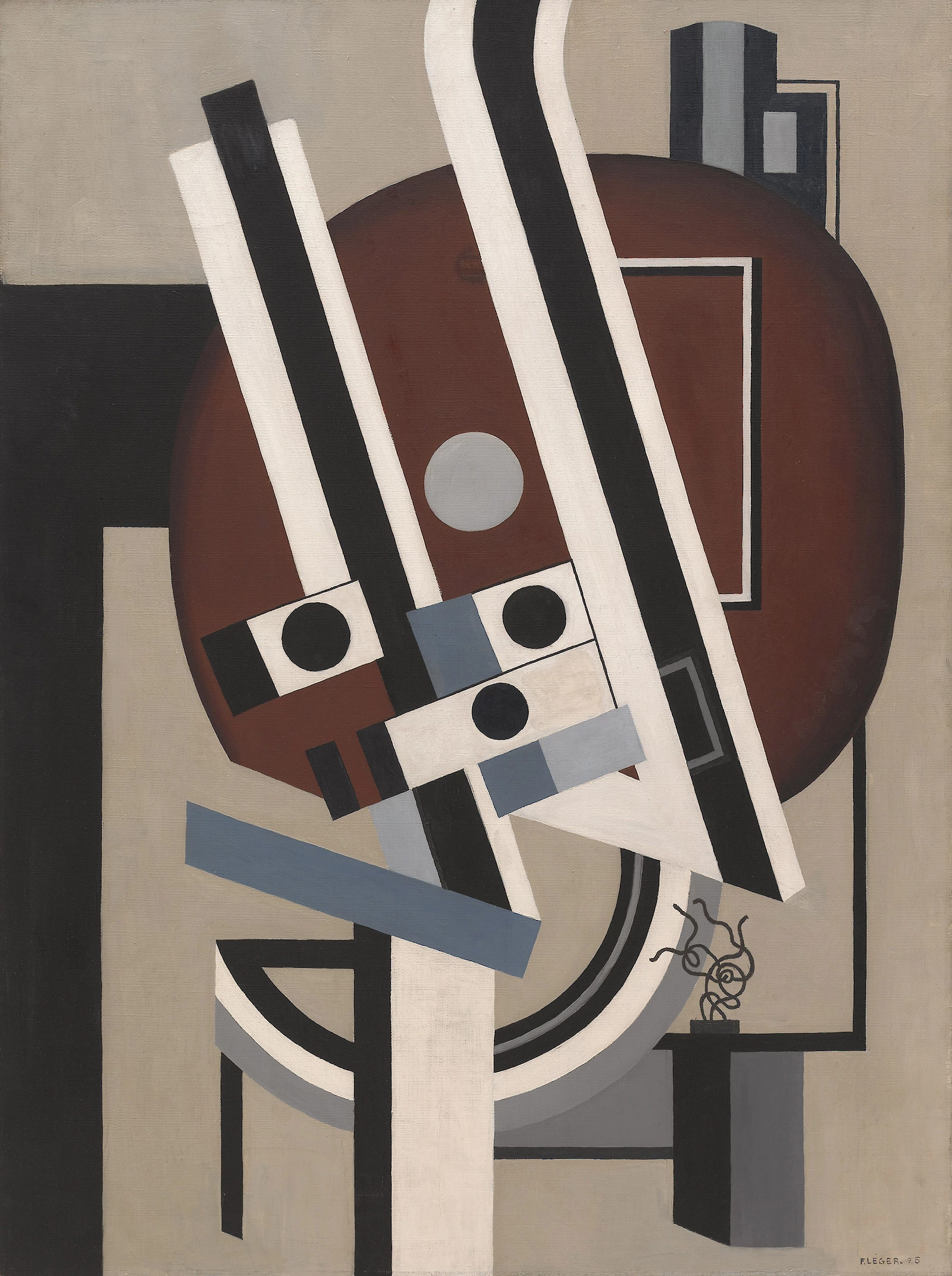

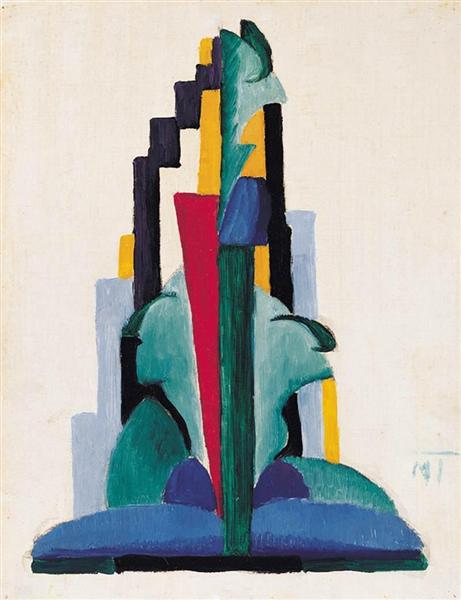

Considered by critics and the artist himself to be his pivotal contribution to the at the Paris Exhibition of 1925: its presence played a highly symbolic role in the origin and development of Art Deco.

Featuring the Italian national colors superimposed on a dark blue and sky-blue background, the “prismatic” arrangement focuses on a schematic male figure with a star-shaped head, symbolizing Italy. Also a self-portrait of Balla himself, it radiates “noise-forms” that take the artist’s varied experiences of Futurist painting and synthesizes them.

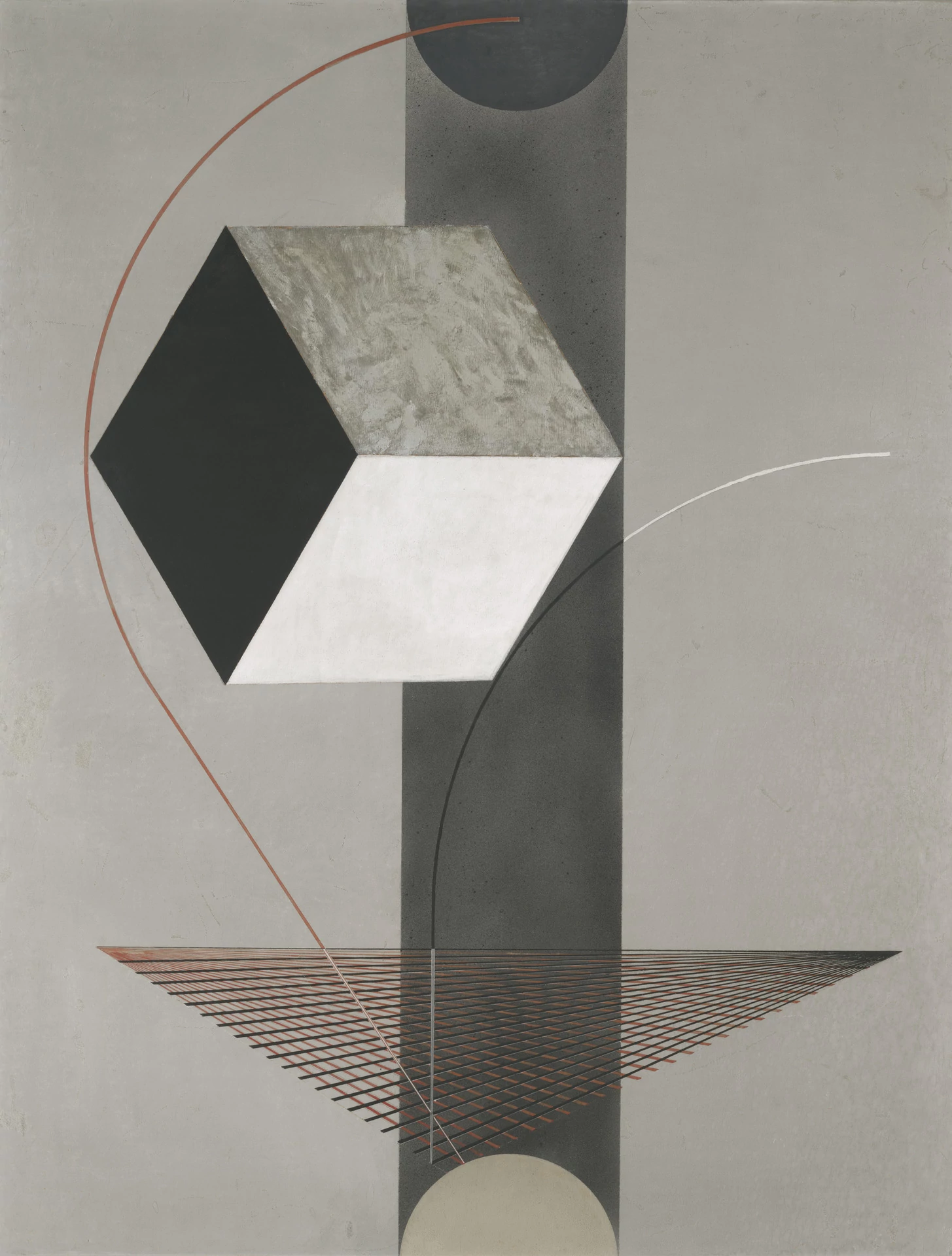

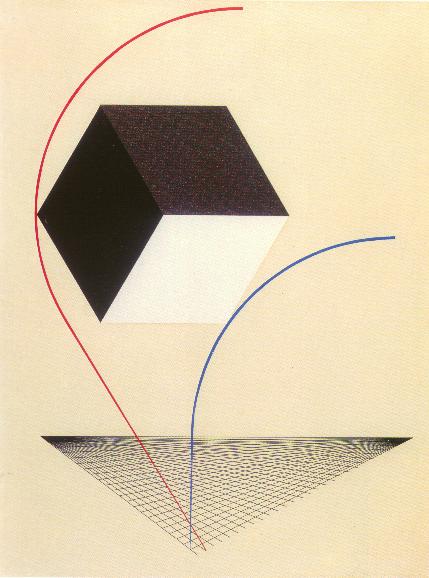

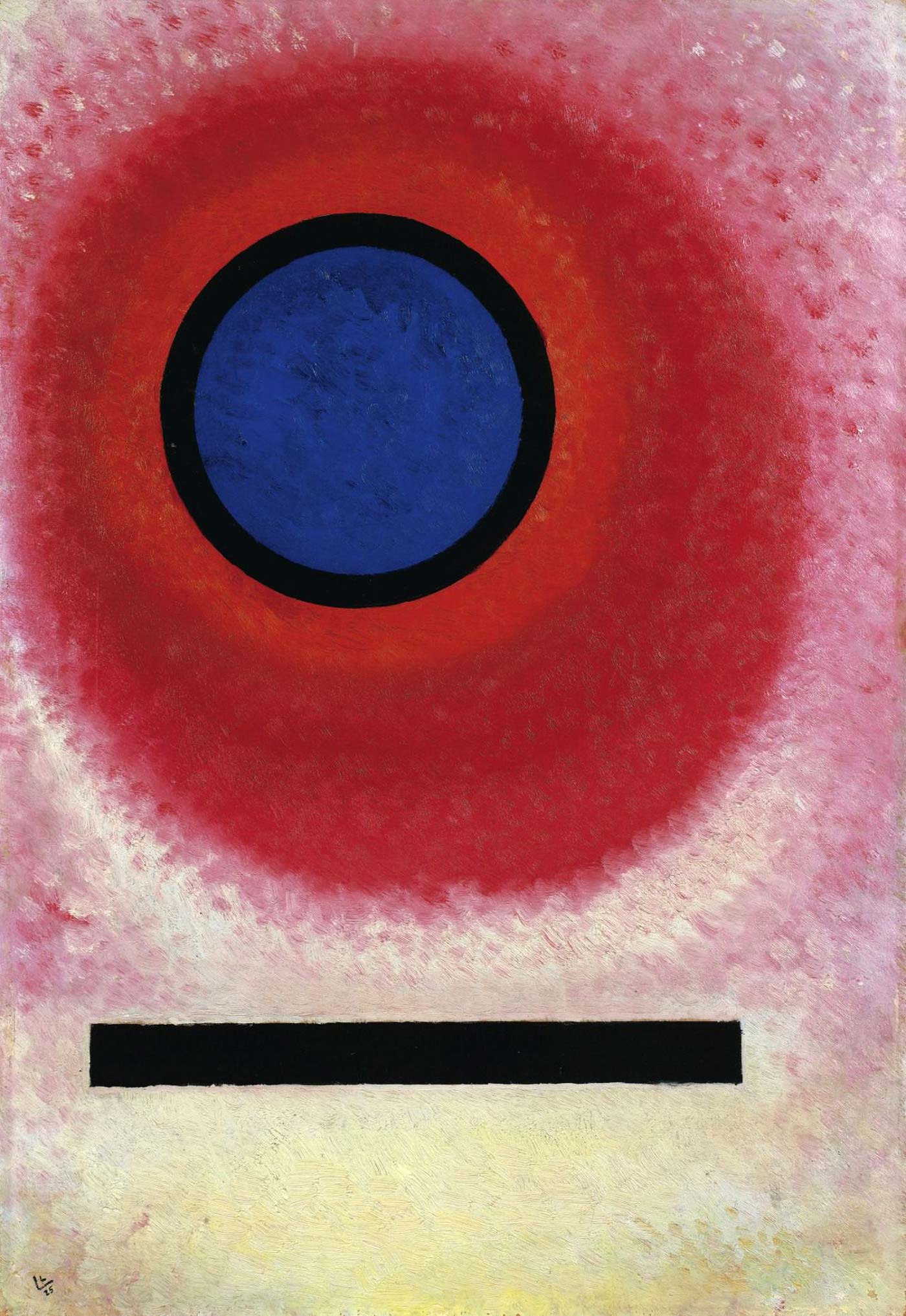

From MOMA’s “Inventing Abstraction” series.

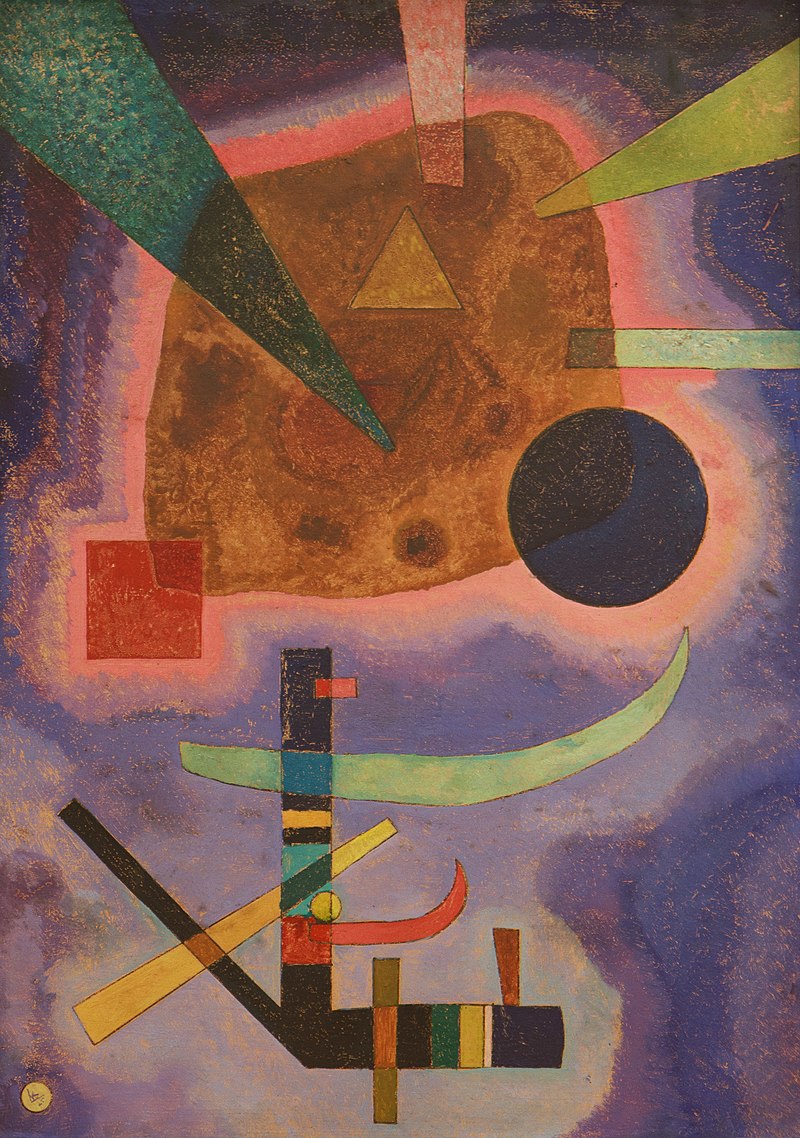

Kandinsky presented the painting to his nephew Alexandre Kojève, whose lectures on Hegel (Paris, 1933–1939) would have an immense influence on 20th-century French philosophy.

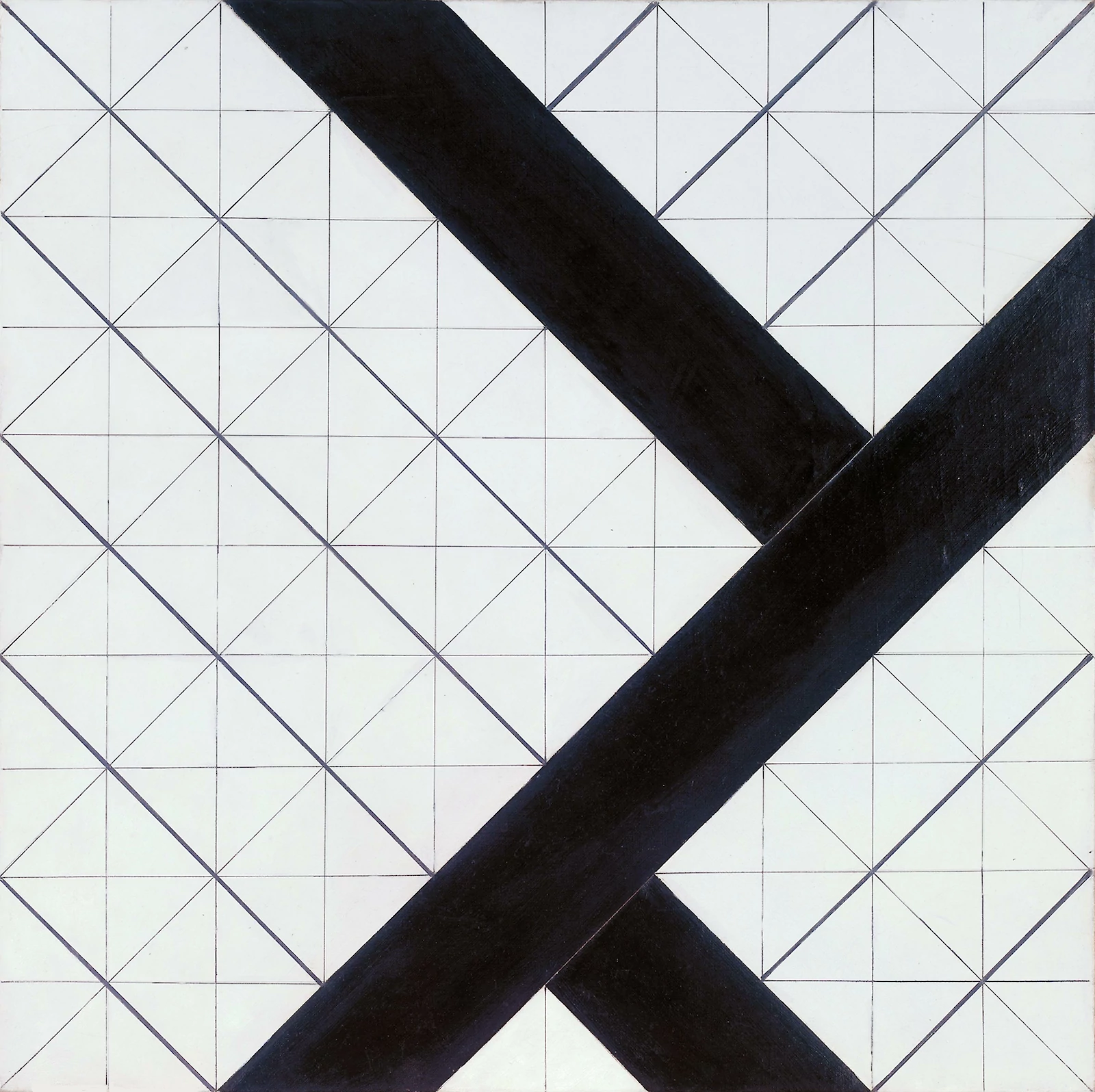

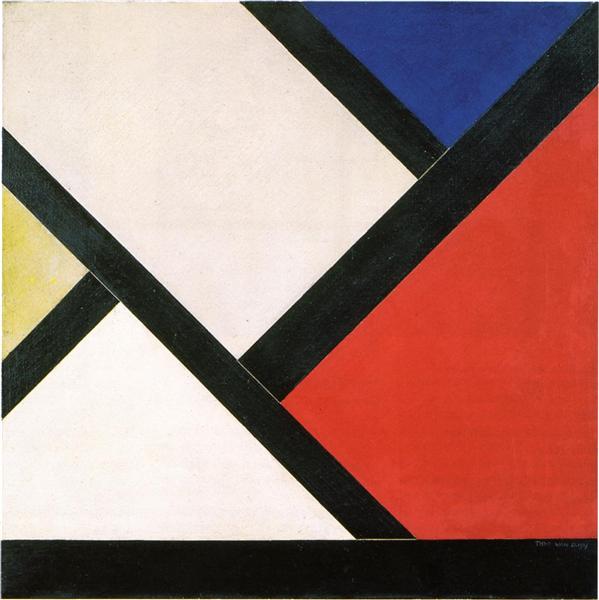

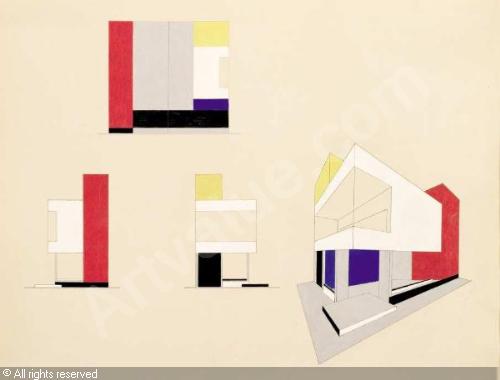

Mondrian — the great diagrammer — insisted that only vertical and horizontal lines were permissible in abstract art. When Van Doesburg made explicit the diagonal axes only implied in his earlier paintings, Mondrian resigned from the editorial board of their journal De Stijl and wouldn’t speak with Van Doesburg for two years.

Mondrian wanted to create a harmonious art that could function effectively as a symbol for a harmonious society, free from passions and conflicts; it’s a vision of the “spiritual” dimension. Van Doesburg wanted to express the dynamism of modern life. He was particularly enthused by the movements of dancers.

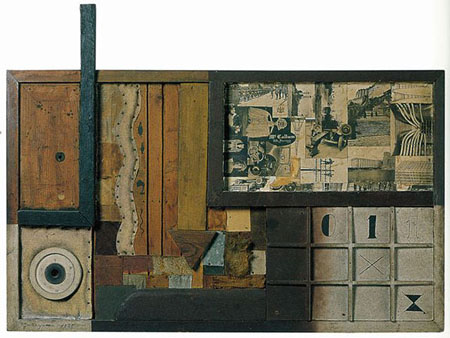

Among the works made after Tomoyoshi Murayama’s return to Tokyo in 1923, Construction (1925) comprises miscellaneous wood panels hammered together into a large rectangular composition, with strips of fabric, leather and metal as well as painted details adding to the mélange of shapes and textures. Framed in the work’s upper-right quadrant is a loosely layered collage of newsprint images and advertisements from far-off shores: a phalanx of soldiers, men working on overhead electric wires, a logo for McCallum Silk Hosiery.

Anni Albers, initially known as a textile artist, used the art of weaving both to make functional materials like draperies and upholstery fabrics and to create one-of-a-kind wall-hangings that function the way that pure abstract painting does. She considered these abstractions to be “visual resting places” that provided a welcome diversion from the vicissitudes of everyday life.

Stölzl was the leader of the Bauhaus’s weaving workshop. After 1922 she moved towards abstract patterns based on a regular grid.

MORE RADIUM AGE SCI FI ON HILOBROW: RADIUM AGE SERIES from THE MIT PRESS: In-depth info on each book in the series; a sneak peek at what’s coming in the months ahead; the secret identity of the series’ advisory panel; and more. | RADIUM AGE: TIMELINE: Notes on proto-sf publications and related events from 1900–1935. | RADIUM AGE POETRY: Proto-sf and science-related poetry from 1900–1935. | RADIUM AGE 100: A list (now somewhat outdated) of Josh’s 100 favorite proto-sf novels from the genre’s emergent Radium Age | SISTERS OF THE RADIUM AGE: A resource compiled by Lisa Yaszek.