RADIUM AGE ART (1920)

By:

July 26, 2024

A series of notes regarding proto sf-adjacent artwork created during the sf genre’s emergent Radium Age (1900–1935). Very much a work-in-progress. Curation and categorization by Josh Glenn, whose notes are rough-and-ready — and in some cases, no doubt, improperly attributed. Also see these series: RADIUM AGE TIMELINE and RADIUM AGE POETRY.

RADIUM AGE ART: 1900 | 1901 | 1902 | 1903 | 1904 | 1905 | 1906 | 1907 | 1908 | 1909 | 1910 | 1911 | 1912 | 1913 | 1914 | 1915 | 1916 | 1917 | 1918 | 1919 | 1920 | 1921 | 1922 | 1923 | 1924 | 1925 | 1926 | 1927 | 1928 | 1929 | 1930 | 1931 | 1932 | 1933 | 1934 | 1935 | THEMATIC INDEX.

In Cologne, Max Ernst, Johannes Baargeld, and Hans (aka Jean) Arp launched a controversial Dada exhibition in 1920 which focused on nonsense and anti-bourgeois sentiments. Cologne’s Early Spring Exhibition was set up in a pub, and required that participants walk past urinals while being read lewd poetry by a woman in a communion dress. The police closed the exhibition on grounds of obscenity, but it was re-opened when the charges were dropped.

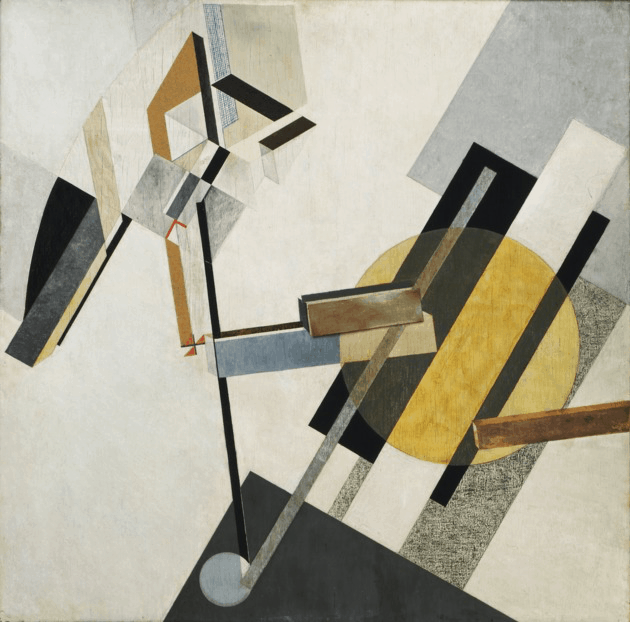

In 1920 Lissitzky coined the term “Proun” — an acronym for the Russian words meaning “project for the affirmation of the new” — to refer to a series of abstract works that combined the Suprematist lexicon of geometric, monochromatic forms with tools of architectural rendering.

Constructivism first appears as a term in Gabo’s Realistic Manifesto of 1920. Constructivism as theory and practice was derived largely from a series of debates at the Institute of Artistic Culture (INKhUK) in Moscow, from 1920 to 1922. After deposing its first chairman, Wassily Kandinsky, for his ‘mysticism’, The First Working Group of Constructivists (including Liubov Popova, Alexander Vesnin, Rodchenko, Varvara Stepanova, and the theorists Aleksei Gan, Boris Arvatov and Osip Brik) would develop a definition of Constructivism as the combination of faktura: the particular material properties of an object, and tektonika, its spatial presence.

Publication of the “Realistic Manifesto,” a Constructivist text, by Naum Gabo with his brother Anton Pevsner in Moscow.

Precisionism is a modernist art movement that emerges in the United States c. 1920. Influenced by Cubism, Purism, and Futurism. Precisionist artists reduced subjects to their essential geometric shapes, eliminated detail, and often used planes of light to create a sense of crisp focus and suggest the sleekness and sheen of machine forms.

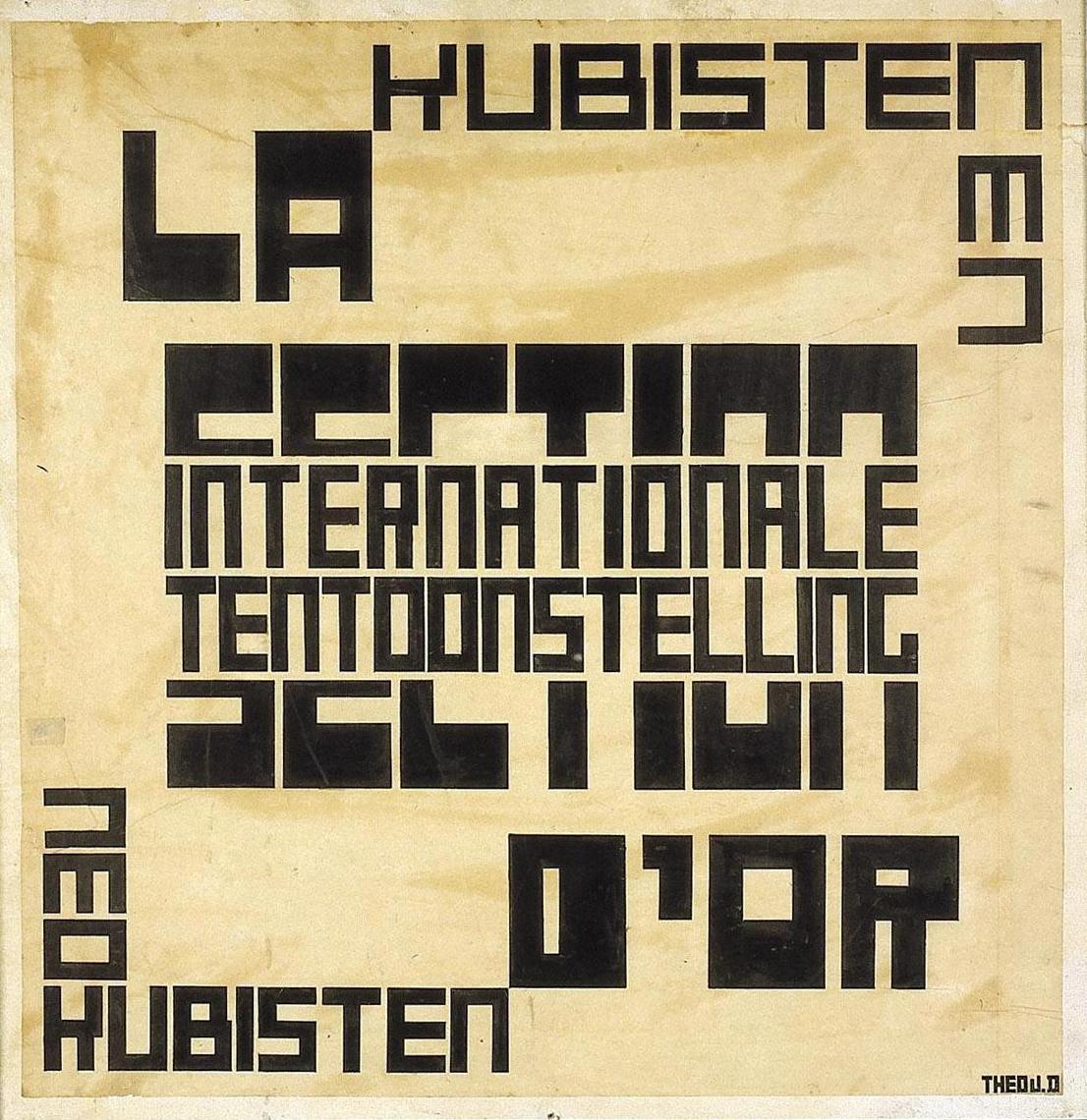

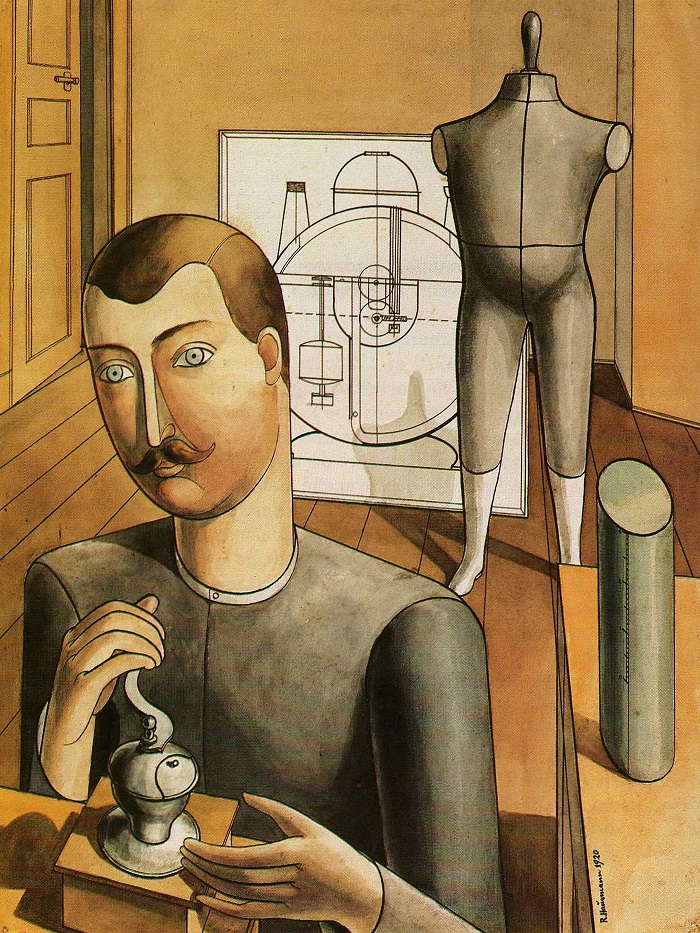

The New Objectivity (Neue Sachlichkeit) is a movement in German art that arises c. 1920 as a reaction against expressionism. The term was coined by Gustav Friedrich Hartlaub, the director of the Kunsthalle in Mannheim, who used it as the title of an art exhibition staged in 1925 to showcase artists who were working in a post-expressionist spirit. These artists — who included Max Beckmann, Otto Dix, George Grosz, Christian Schad, Rudolf Schlichter and Jeanne Mammen — rejected the self-involvement and romantic longings of the expressionists, and issued a call to arms for public collaboration, engagement, and rejection of romantic idealism.

Katherine Dreier, Man Ray and Marcel Duchamp form the Société Anonyme.

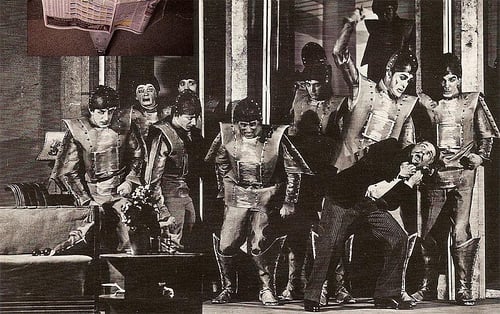

Publication in Prague of Karel Čapek’s proto-sf drama R.U.R: Rossum’s Universal Robots, which introduces the term “robot.”

Mondrian’s Le Neo-Plasticisme (Principe général de l’equivalence plastique), published in 1920 by Editions de l’Effort Moderne, is dedicated to “the man of the future.”

Ernest Rutherford predicts the existence of the neutron.

Einstein’s 1920 address “Ether and the Theory of Relativity” makes clear that his theory of relativity didn’t entirely do away with the “ether” that classical physicists had supposed to fill the spaces between particles and provide the medium for the transmissions of light. In fact, he says here, the general theory of relativity is, in effect, an ether theory: “The recognition of the fact that ’empty space’ in its physical relation is neither homogeneous nor isotropic… has, I think, finally disposed of the view that space is physically empty. But therewith the conception of the ether has gain acquired an intelligible content.”

Also see: RADIUM AGE: 1920.

Speaking of catastrophe, Edward Shanks’s The People of the Ruins (reissued by the MIT Press’s RADIUM AGE series) appears in 1919–1920.

The artist’s friend Walter Benjamin purchased the print in 1921. In the ninth thesis of his 1940 essay “Theses on the Philosophy of History”, Benjamin describes Angelus Novus as an image of the angel of history:

A Klee painting named Angelus Novus shows an angel looking as though he is about to move away from something he is fixedly contemplating. His eyes are staring, his mouth is open, his wings are spread. This is how one pictures the angel of history. His face is turned toward the past. Where we perceive a chain of events, he sees one single catastrophe which keeps piling wreckage upon wreckage and hurls it in front of his feet. The angel would like to stay, awaken the dead, and make whole what has been smashed. But a storm is blowing from Paradise; it has got caught in his wings with such violence that the angel can no longer close them. The storm irresistibly propels him into the future to which his back is turned, while the pile of debris before him grows skyward. This storm is what we call progress.

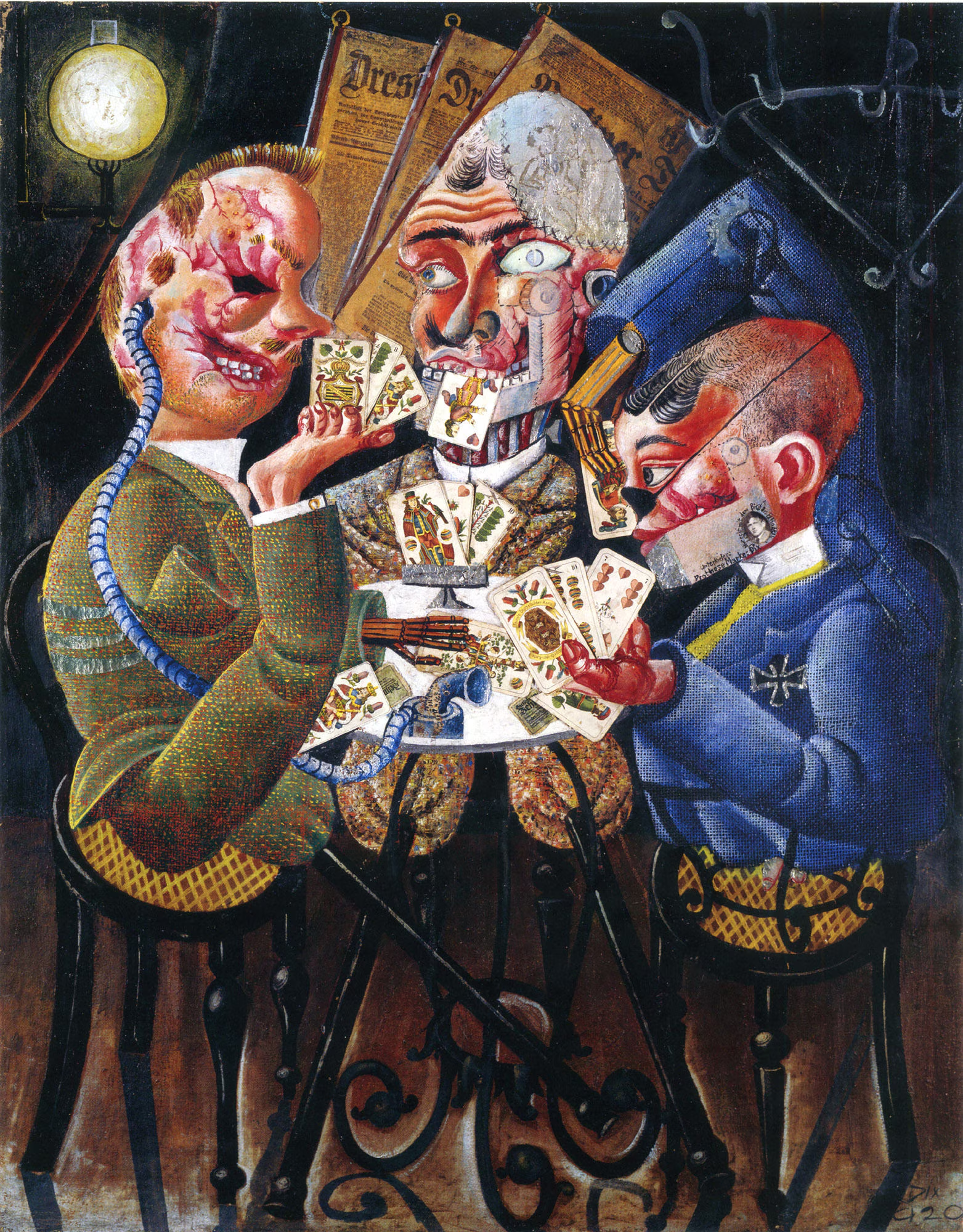

From MoMA’s website: “We’re looking at a group of three German military officers, the shattered hulks of their bodies speaking to the devastation wreaked on Germany and on the heroic figure of the invulnerable war hero by WWI. As you look through Dix’s painting you see this contrast between the mechanical and the organic, between flesh and prosthetics, between the viscous application of oil paint and the materials of montage or collage. Along the lower edge of the composition, this play between organic and inorganic is particularly poignant in the similarities between the officer’s prosthetic legs and the wooden legs of the chairs. There is a sympathy involved in his portrayal of these dysfunctional figures, who are reduced to mere shadows of their former self.”

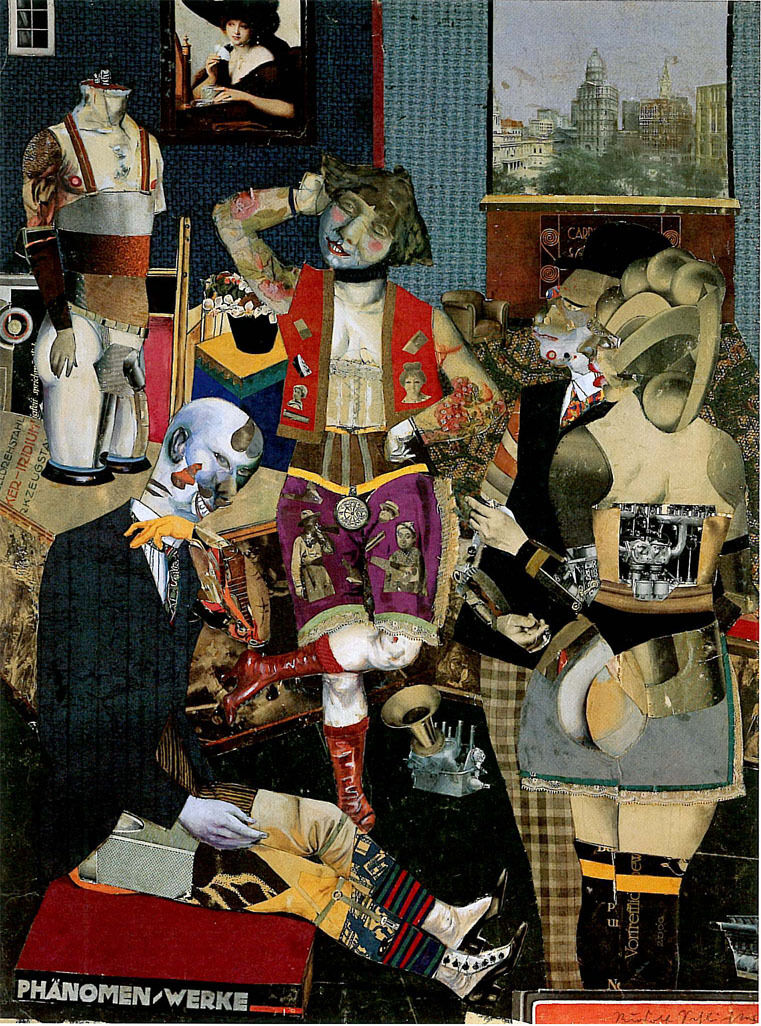

An evocative visual reaction to the birth of industrial advertising and ideals of beauty it furthered. In the work, a woman has not a head, but a lightbulb. A car tyre and a lever box her in on either side. BMW logos multiply behind her, while a hand holding a circular pocket watch emerges from behind a pouf of hair. Corporations and new technologies, apparently, have overtaken the subject’s individuality, while the clock suggests how time and labour were being monetized in new ways.

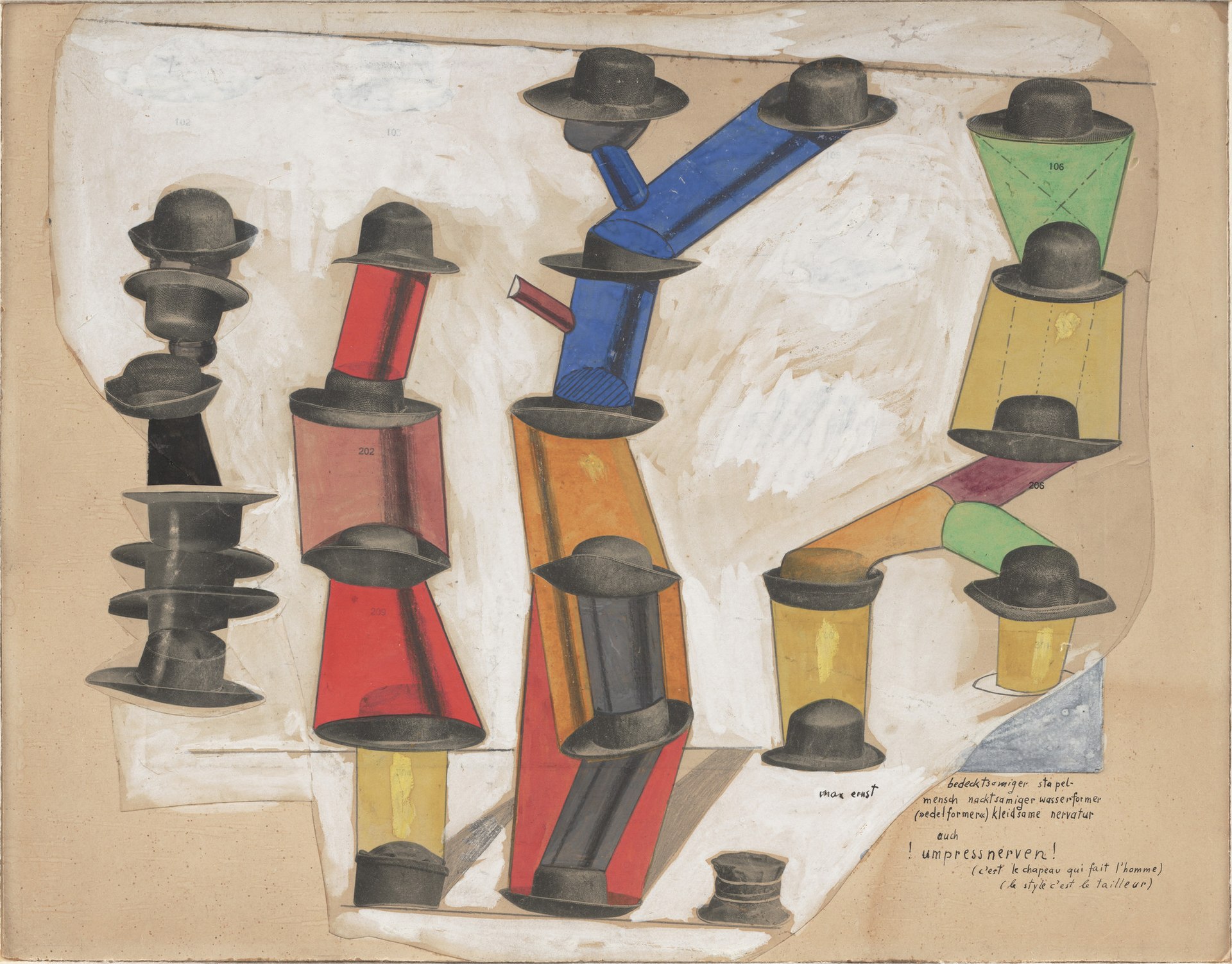

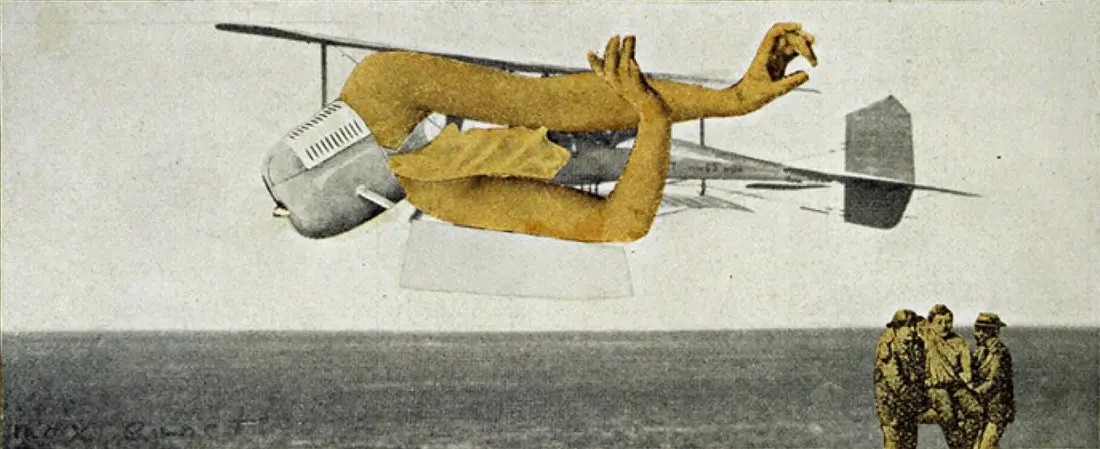

The Hat Makes the Man (1920) is a collage by the German dadaist/surrealist Max Ernst. It is composed of cut out images of hats from catalogues linked by gouache and pencil outlines to create abstract anthropomorphic figures. The Dada movement often depicted modern man as a conformist automaton.

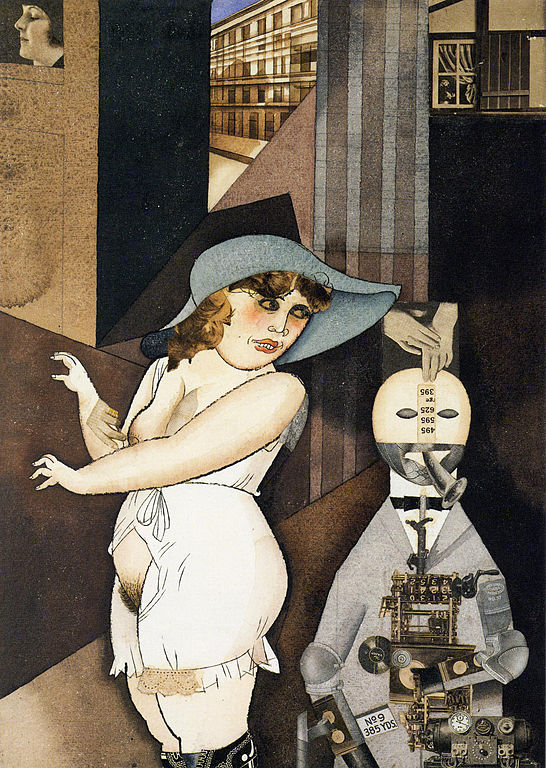

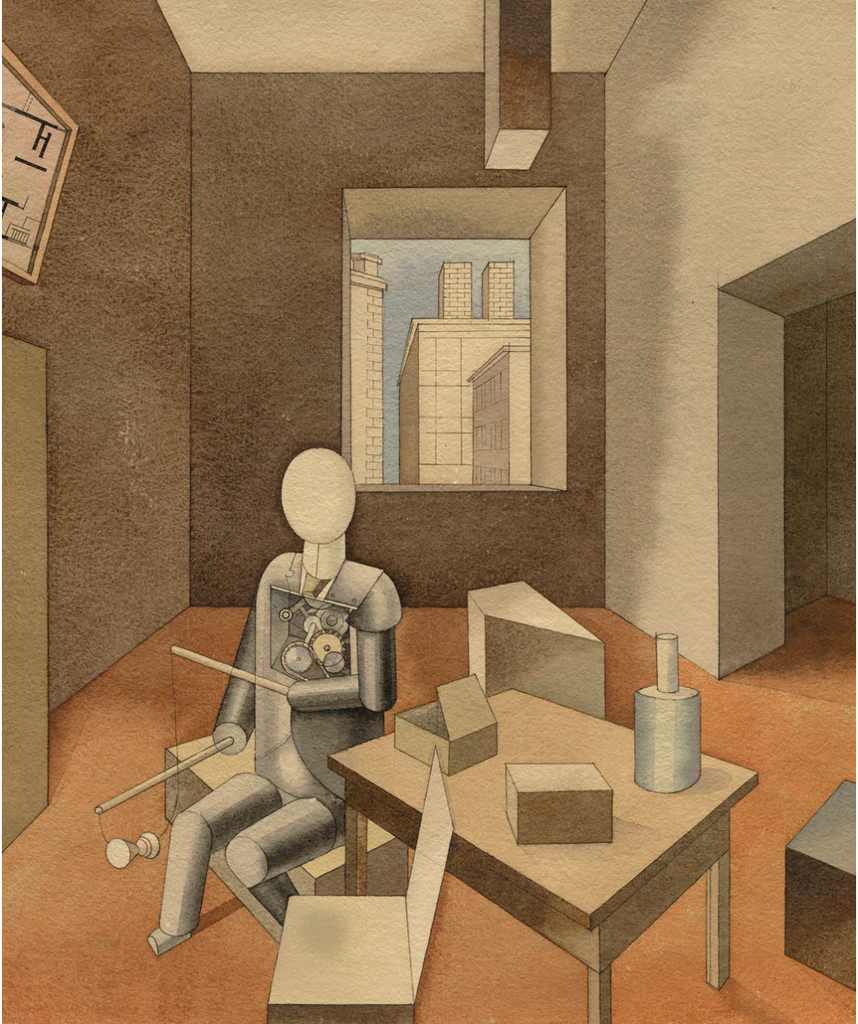

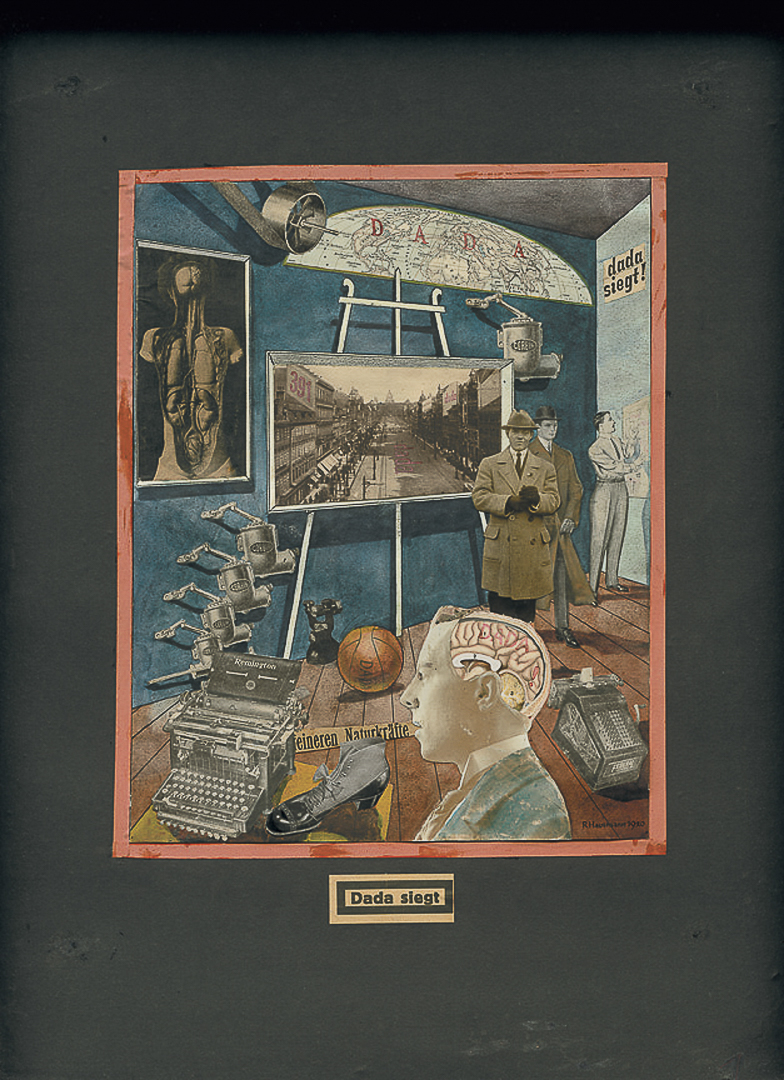

A multimedia sculpture constructed by George Grosz and John Heartfield. The work forces viewers to confront the reality of horrors inflicted by those involved in the First World War. The subject (the “Spiesser” or “Philistine,” represented here by a store-bought mannequin) is forcibly transformed by the world around him, as seen in the way that his body parts are replaced by fragments of the modern world such as the head by a light bulb and leg by a metal rod. In this work, Grosz and Heartfield indicated the way in which the world was changing those in it, forcing the audience to abandon their escapist art and reconcile with the transforming world in front of them.

I’ve also seen it titled “The Engineer Heartfield.”

From MoMA’s website:

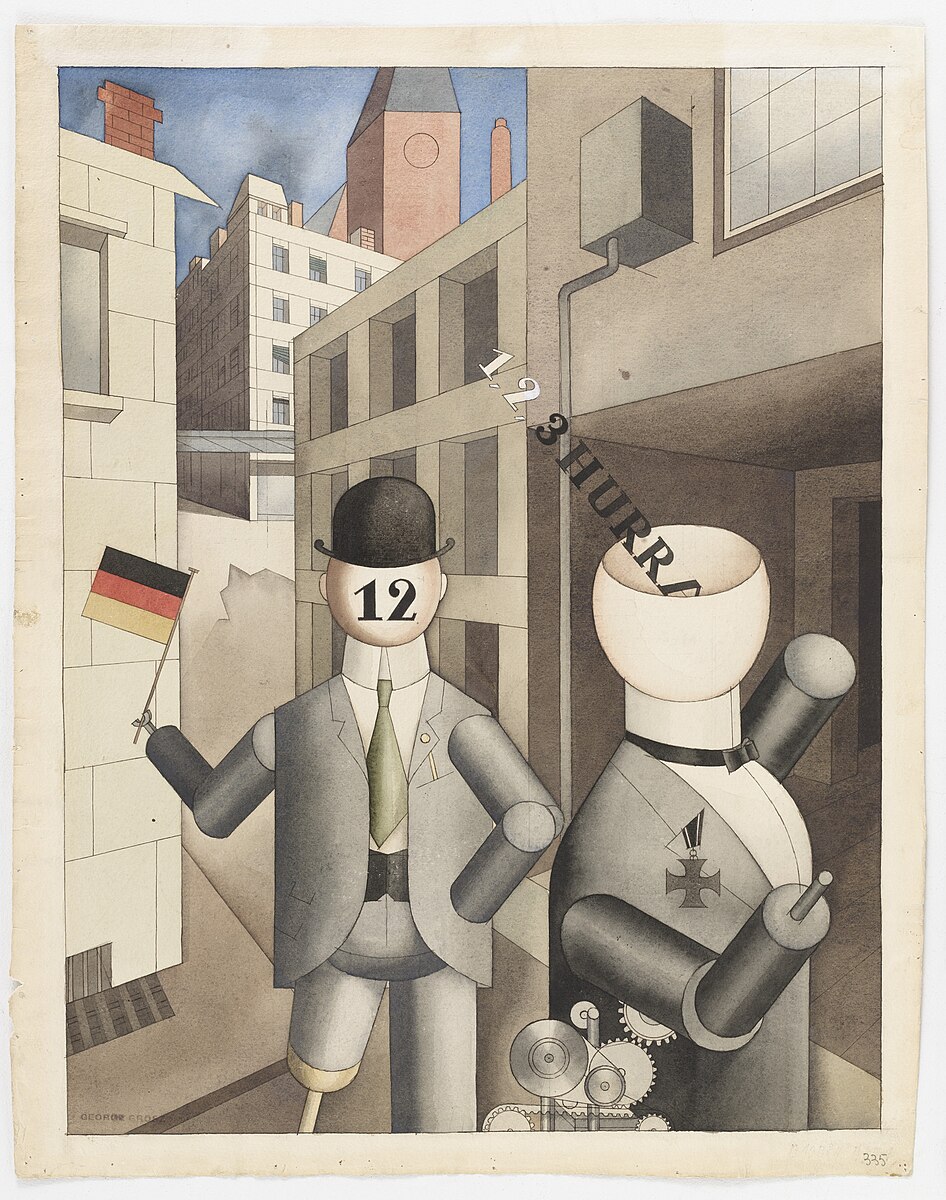

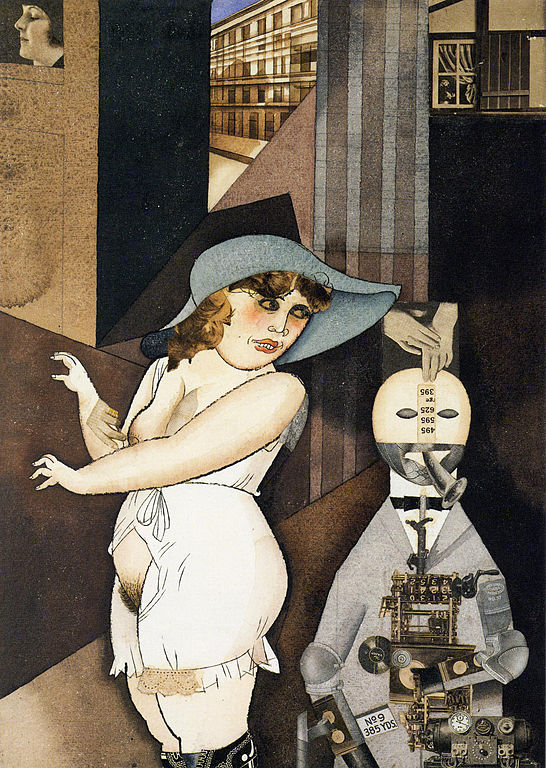

In this work Grosz depicts John Heartfield, a friend, collaborator, and fellow artist involved in Berlin Dada, a politically engaged artistic movement that formed after World War I and was characterized by satire, provocation, and critical social commentary. The portrait combines delicately hued watercolors with printed images and represents Heartfield as bald and grim-faced, with clenched fists and a machine for a heart. The mechanical device indicates his identity as a constructor (monteur) of photomontages, collages made with cut-and-pasted photographs. Heartfield called himself a monteur-dada rather than an artist, and he intended his assembled images for mass reproduction only, in magazines and on book covers and posters.

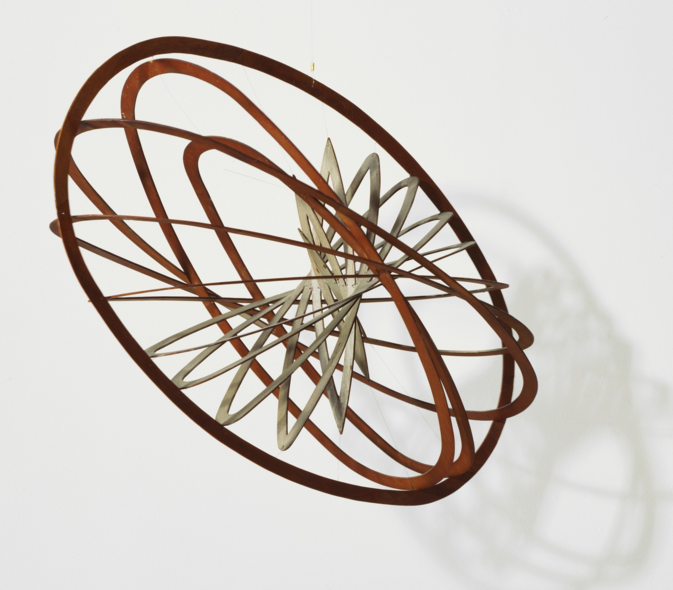

A three-dimensional object resembling a gyroscope, and suggesting “a chart of planetary orbits, a cosmic struture” — from the book MoMA Highlights: 350 Works from the Museum of Modern Art New York (second edition, 2004). Rodchenko’s interest in mathematical systems reflects the scientific bent of the Russian Constructivists, artists who aspired to create a radically new, radically rational art for the society that came into being with the Russian Revolution.

Demuth was a principal member of the Precisionist movement that emphasized sharp lines and clear geometric shapes. Pictured in the center of this composition is the steeple of the old Center Methodist Episcopal Church in Provincetown, Massachusetts (now the Provincetown Public Library).

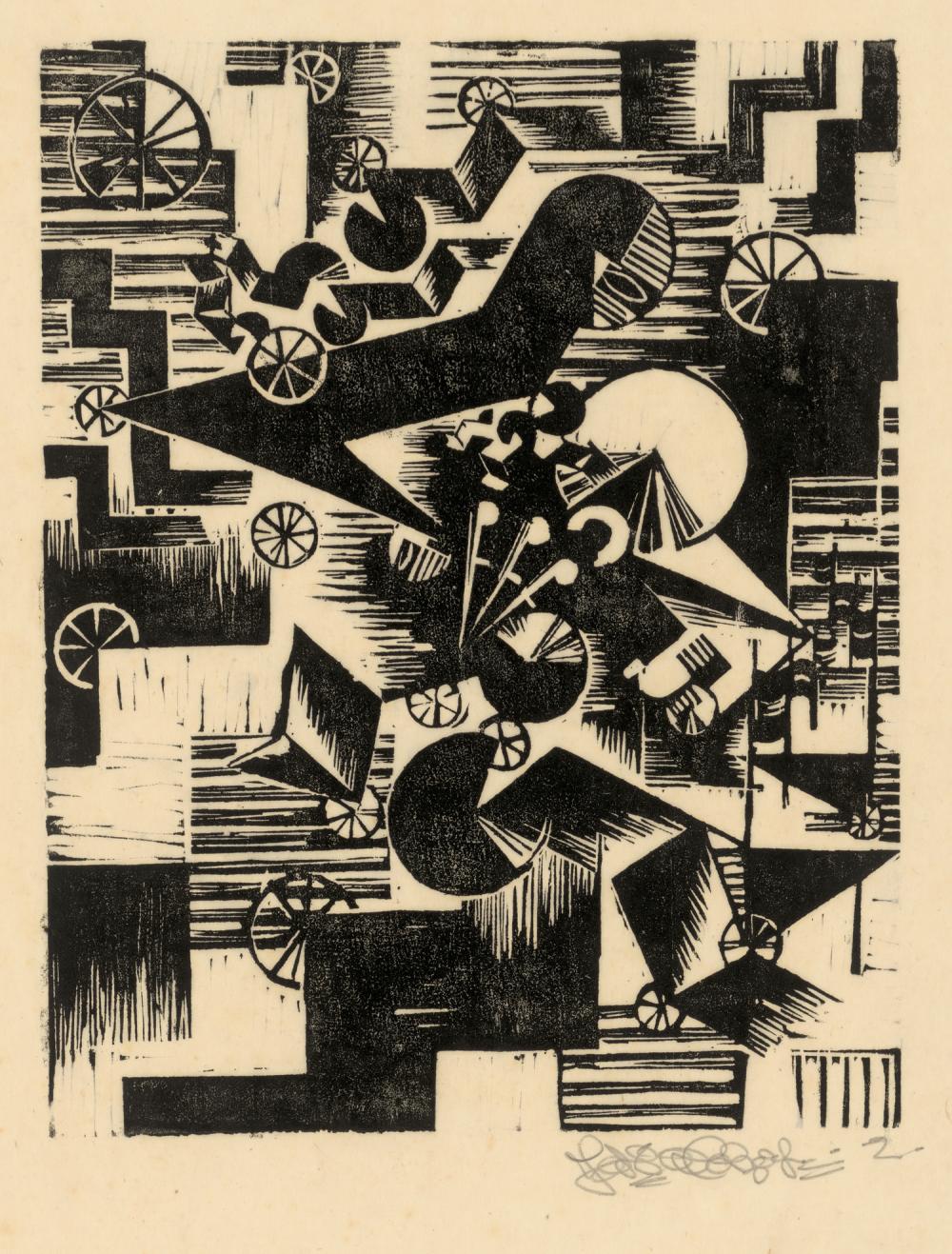

Villon’s lithograph was used to illustrate the cover of Bill Richardson’s Borges and Space (2012). See below.

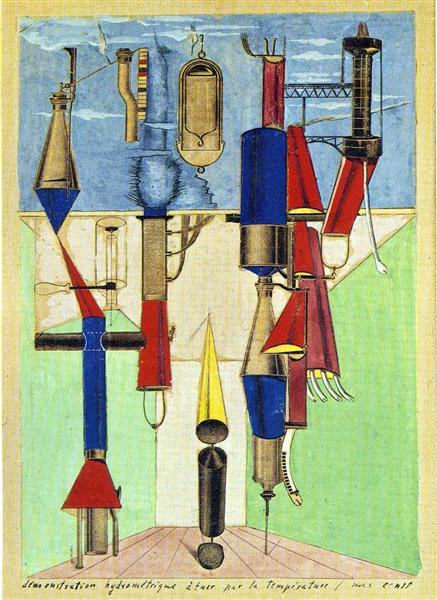

A gridlike structure, consisting of several rectangular and predominantly opaque shapes, grows out of the base shape, while a translucent yellow sphere is suspended above it.

Is this a utopian (political) work? Or — like much abstract art of the period — was Lissitzky’s disruption of the traditional relationship between the viewer and the picture plane understood to have a predominantly cosmic dimension? Was it seen as an example of the dematerialized and cosmic dimension of Suprematist theories promoted by Malevich, the progenitor of the movement? This essay from MoMA’s publication POST suggests that “the political resonance of the Prouns is ambiguous.”

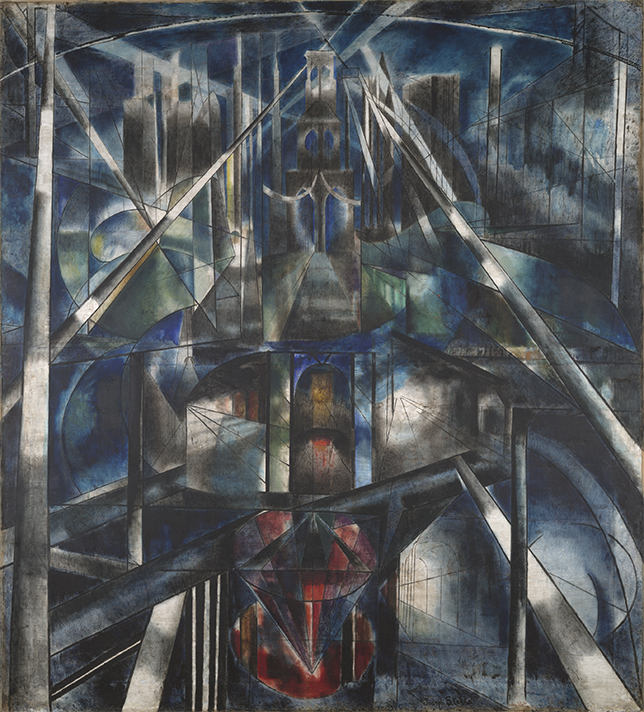

Depicts a fictional part of the elevated railway in Manhattan, painted in a style influenced by cubism and futurism.

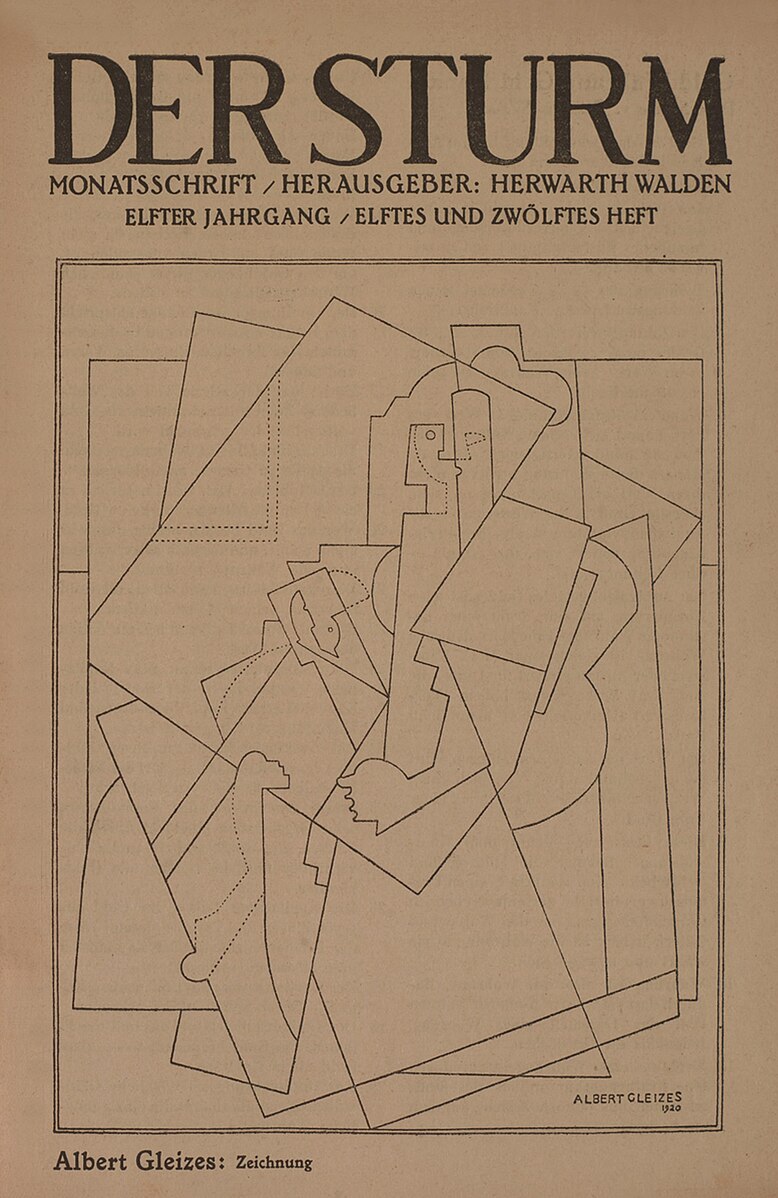

Gleizes’ drawing would be used as a cover illustration for a 2020 Penguin edition of Edwin A. Abbott’s Flatland. See below.

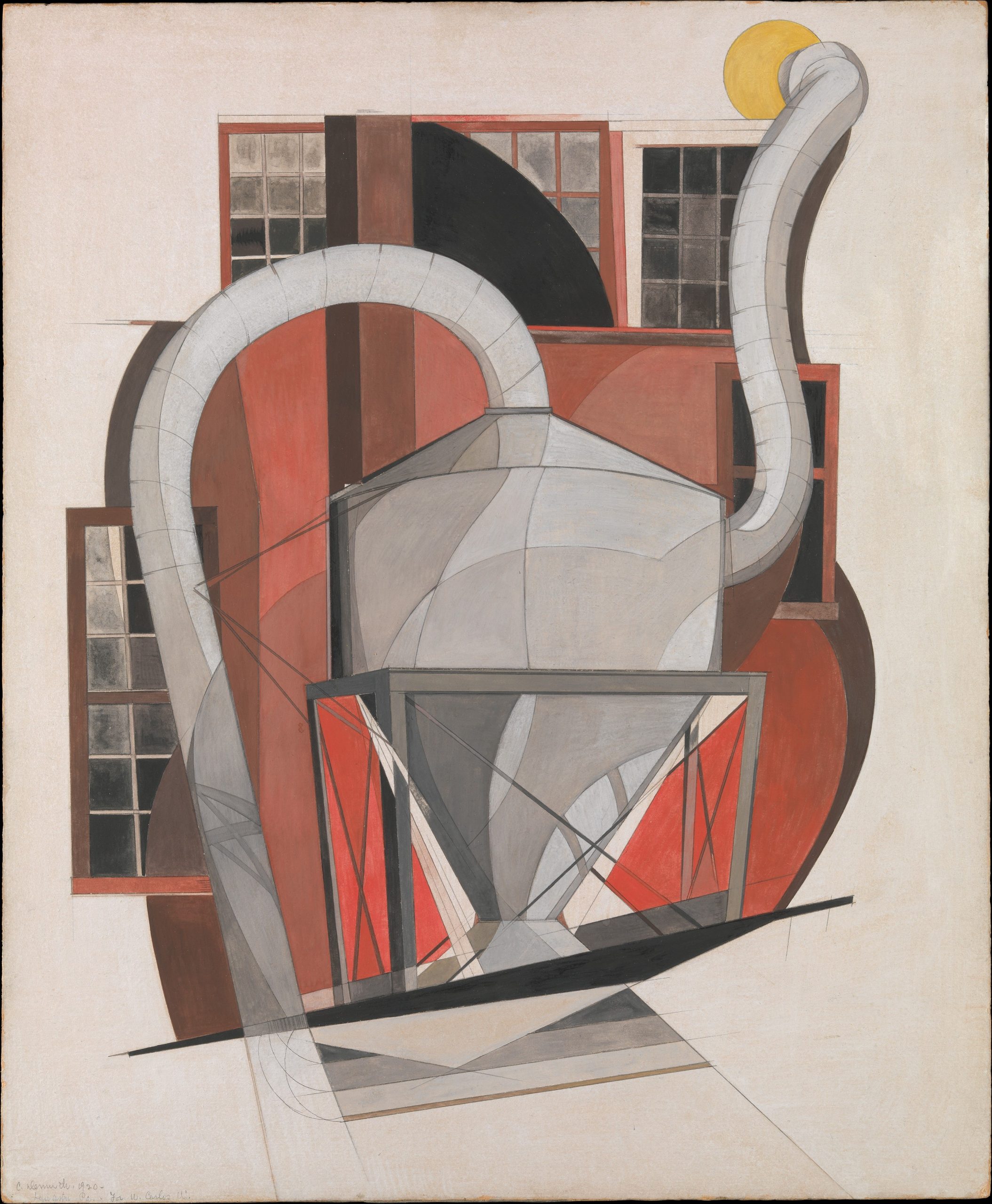

The drawing depicts a piece of industrial machinery in the artist’s hometown of Lancaster, Pennsylvania. Specifically, it’s a cyclone separator set in front of a factory wall.

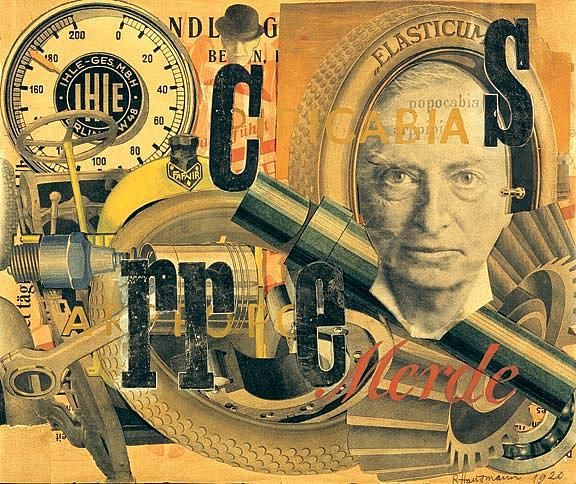

Includes images of tires, a speedometer, nuts and bolts, and, most likely, the head of Henry Ford—inventor of the assembly line and father of mass-produced automobiles.

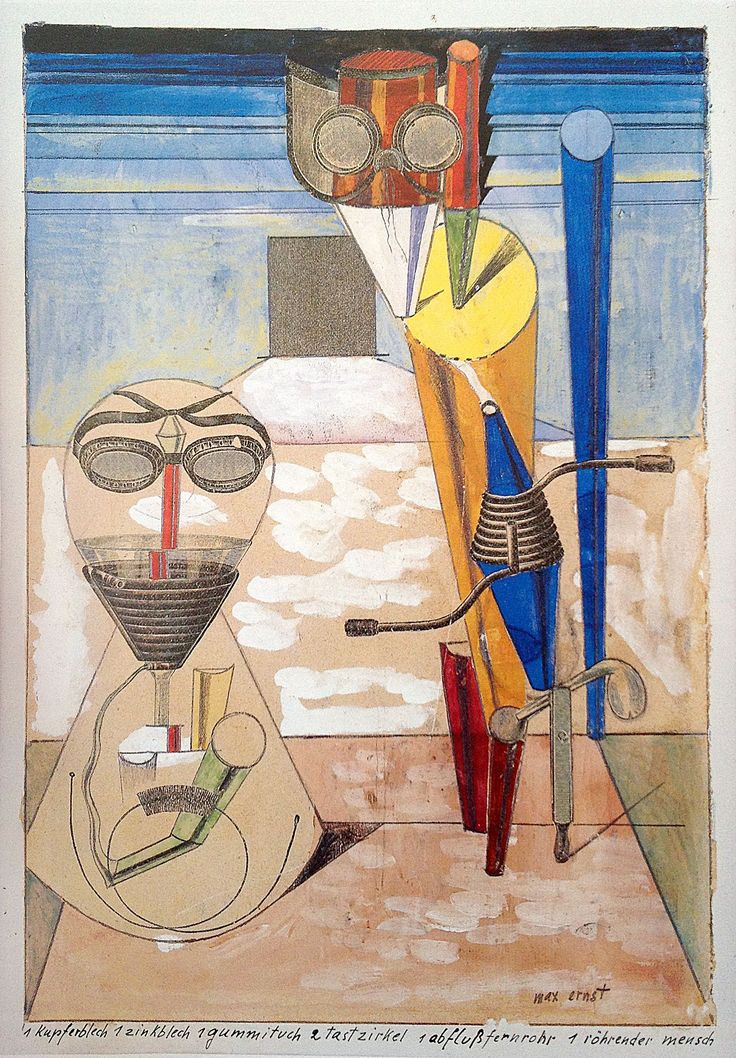

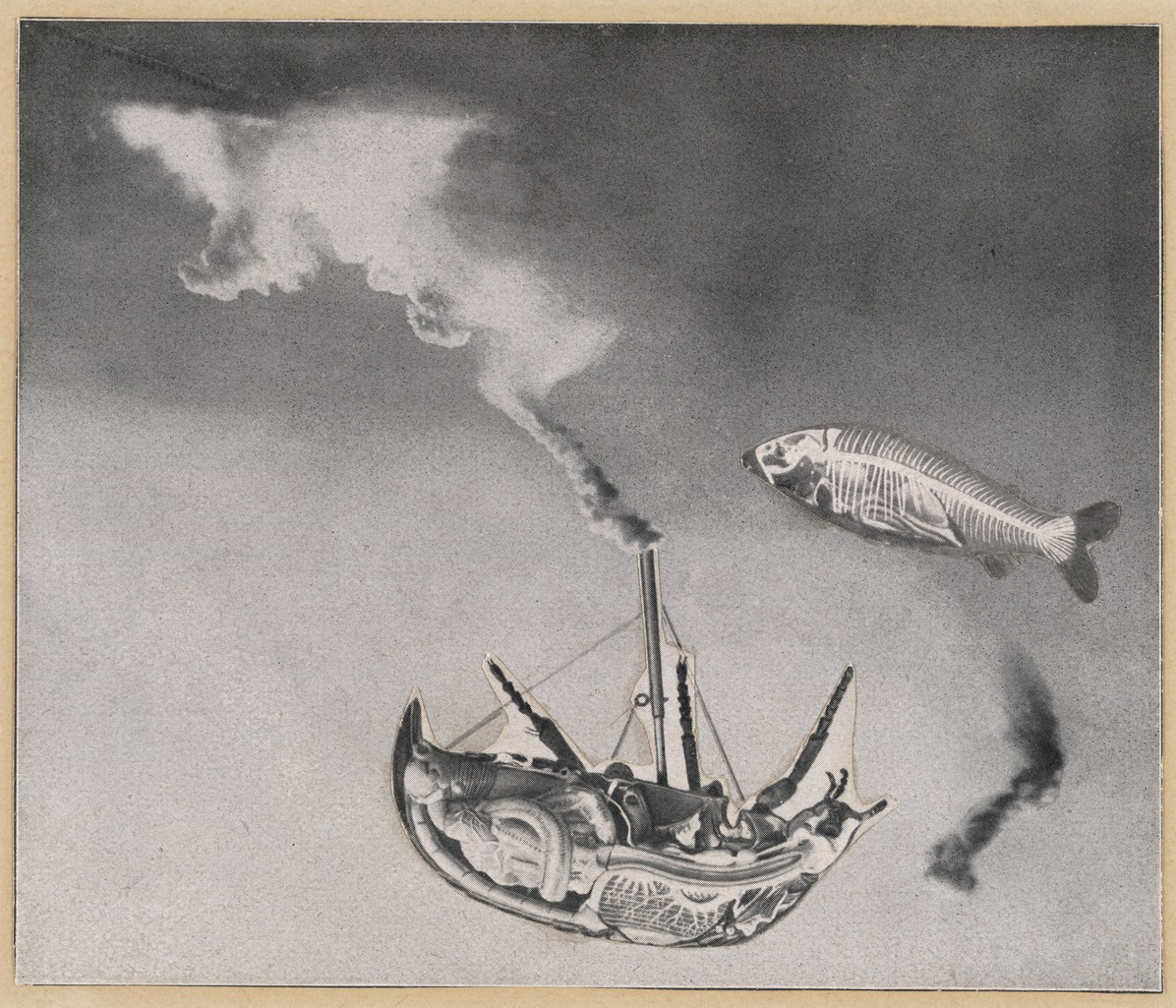

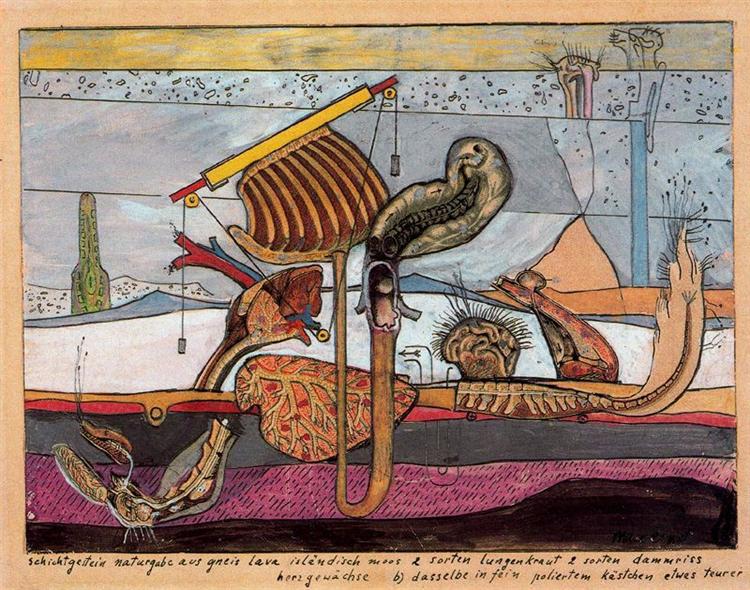

The source for this overpainting is an equine anatomical diagram from a teaching-aids supply catalogue (the Bibliotheca Paedagogica, 1914), which the artist turned upside down. Ernst’s inscription reads: “Stratified rocks, nature’s gift of gneiss lava Icelandic moss 2 kinds of lungwort 2 kinds of ruptures of the perinaeum growths of the heart b) the same thing in a well-polished little box somewhat more expensive.”

Ernst later wrote of the Bibliotheca that “the sheer absurdity of the collection provoked a sudden intensification of the visionary faculties in me.”

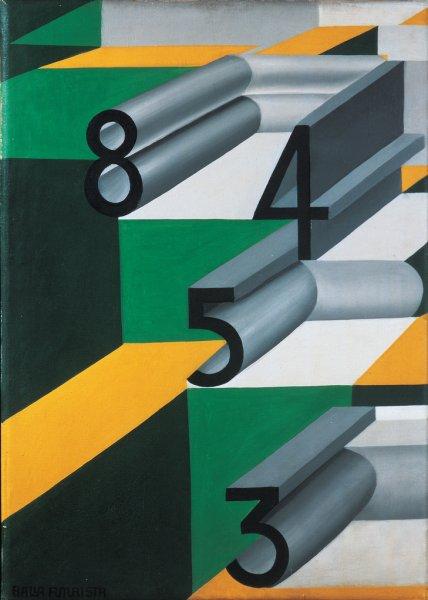

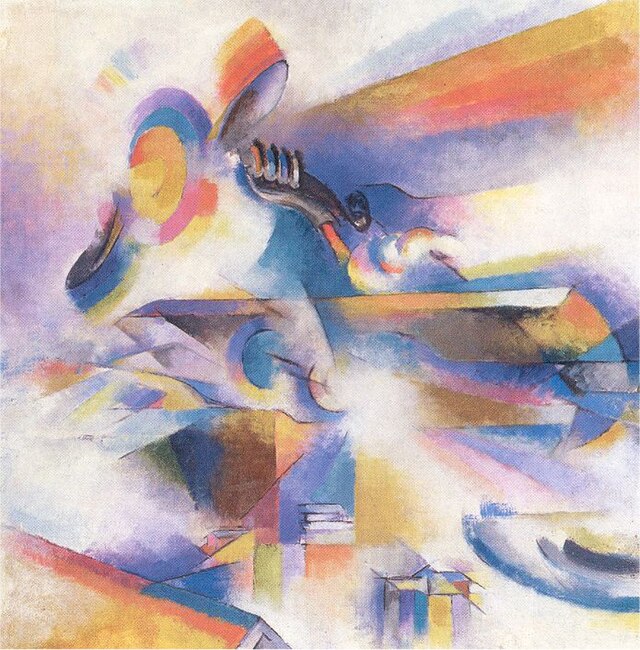

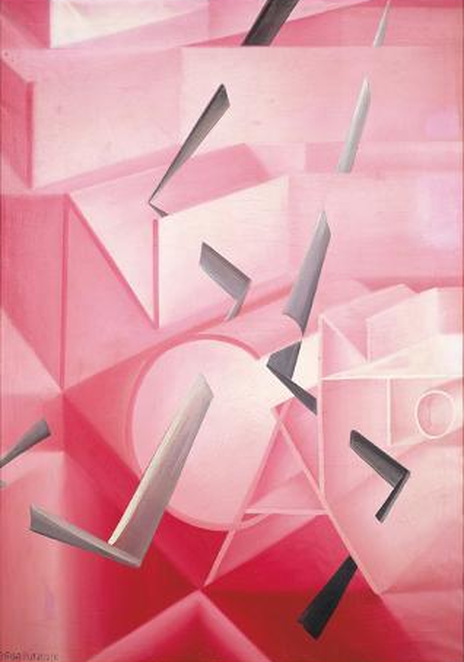

A metaphysical painting in which Balla seeks to translate a state of being into shapes and color. The effect of a broken spell on what was a charmed experience is portrayed by the gray boomerang shapes breaking up the composition of the word “incanto” (enchantment), which can be deciphered in the canvas.

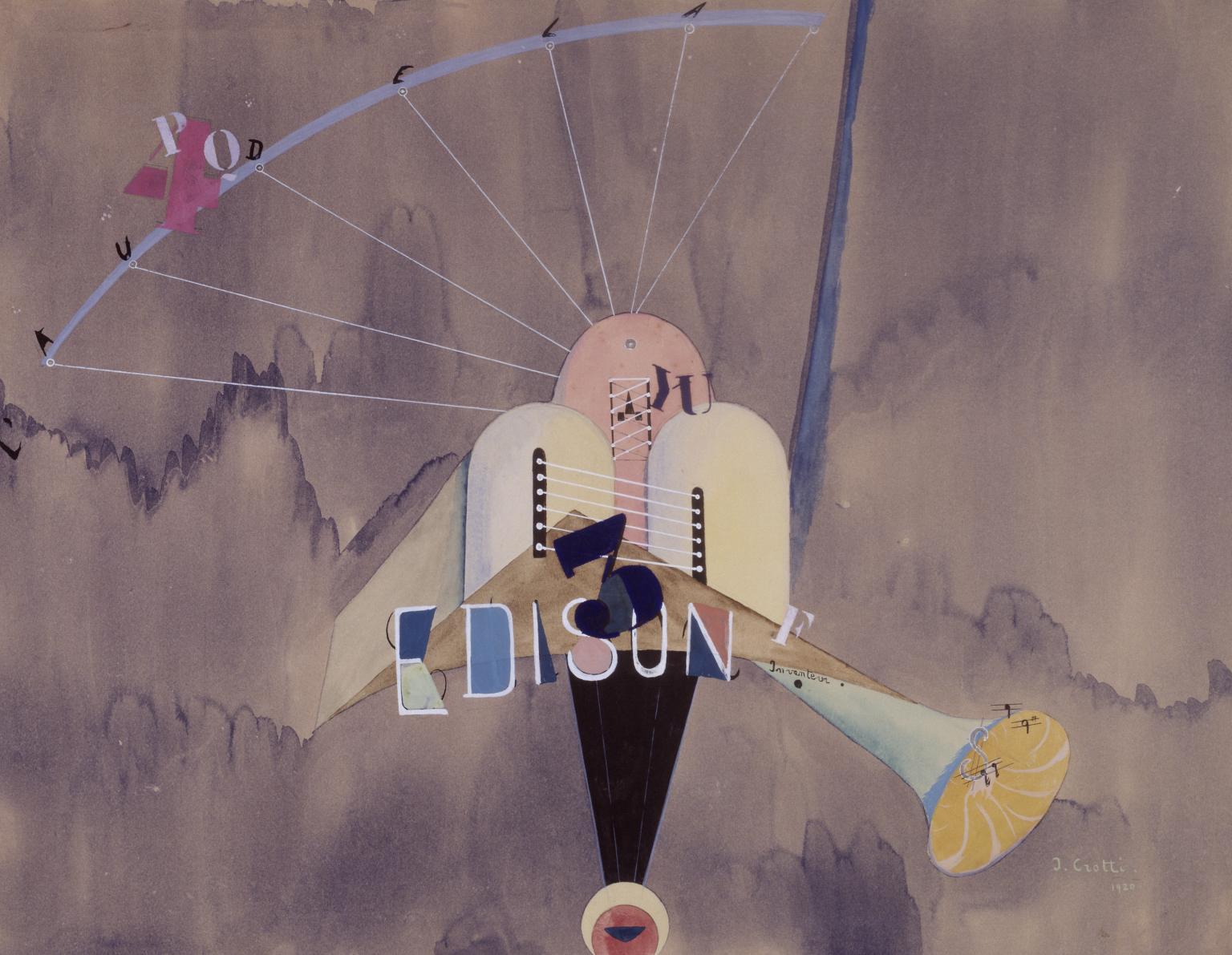

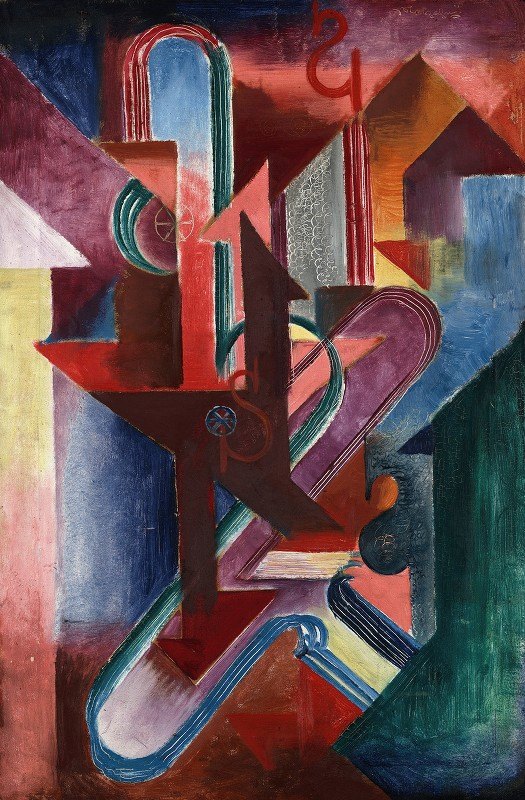

To the deeply spiritual Jean Crotti, abstraction was a tool for grappling with existential questions. It stands as his main stylistic consistency, although he incorporated some figuration and blended elements of Cubism, Orphism, Futurism, and Dada throughout his oeuvre. Crotti and his wife Suzanne Duchamp developed Tabu, an offshoot of Dada distinguished, according to The New York Times critic Holland Cotter, “by its rejection of the negative, anti-art aspects of the original.”

More on PROUNS:

Lissitzky’s Prouns, which the artist began making sometime in 1919, infused the previously flat geometric forms of Suprematism with a sense of virtual architectural space. Instead of depicting two-dimensional planes of color, as Malevich did in his Suprematist compositions, Lissitzky employed axonometric projection. After drawing a geometric figure according to the rules of traditional Renaissance perspective, the artist would rotate the work ninety degrees and add a new volume corresponding to the new orientation.

In the July 1922 issue of the journal Das Kunstblatt, the Hungarian critic and Bauhaus associate Ernst Kállai wpould interpret Lissitzky’s Prouns as models “of technological qualities that mirrored aspects of the universe itself.” He wrote: “A technical planetary system keeps its balance, describes elliptical paths or sends elongated constructions with fixed wings out into the distance, aeroplanes of infinity…. The living, artistic kernel of the construction opens. What are mere utilitarian purposes beside this overflowing energy and dynamism?”

MORE RADIUM AGE SCI FI ON HILOBROW: RADIUM AGE SERIES from THE MIT PRESS: In-depth info on each book in the series; a sneak peek at what’s coming in the months ahead; the secret identity of the series’ advisory panel; and more. | RADIUM AGE: TIMELINE: Notes on proto-sf publications and related events from 1900–1935. | RADIUM AGE POETRY: Proto-sf and science-related poetry from 1900–1935. | RADIUM AGE 100: A list (now somewhat outdated) of Josh’s 100 favorite proto-sf novels from the genre’s emergent Radium Age | SISTERS OF THE RADIUM AGE: A resource compiled by Lisa Yaszek.