MAN’S WORLD (2)

By:

July 18, 2024

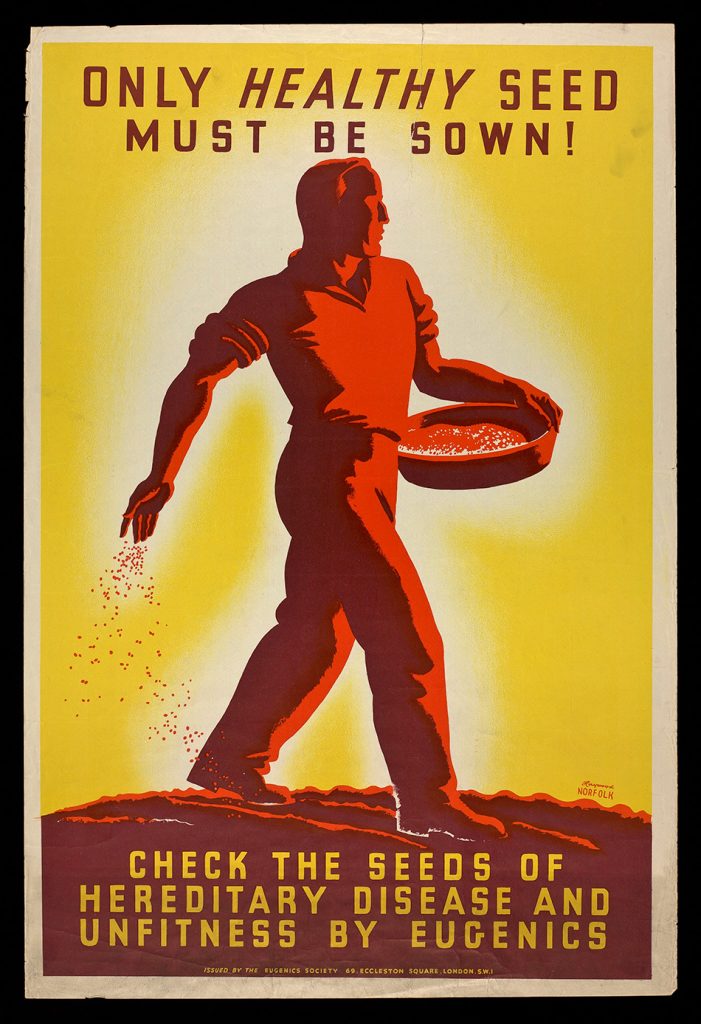

HiLoBooks is pleased to serialize Charlotte Haldane’s 1926 proto-sf novel Man’s World for HILOBROW’s readers. Written by an author married to one of the world’s most prominent eugenics advocates, this ambivalent adventure anticipates both Brave New World and The Handmaid’s Tale. When a young woman rebels against her conditioning, can she break free? Reissued in 2024 (with a new introduction by Philippa Levine) by the MIT Press’s RADIUM AGE series.

ALL INSTALLMENTS: INTRO | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25.

THE VISION OF MENSCH

(cont.)

‘It was Huxley who flung at his contemporaries that sublime challenge in fifteen words which was the parent of Mensch’s philosophy: “I have no faith, very little hope, and as much charity as I can afford.” Faith, child of ignorance; hope, twin of fear; charity, pallid ghost stalking in the wake of greed; could a civilization built on faith, hope, and charity be expected by any scientific thinker to last?

‘The disciples of Plato have as much to answer for as those of Jesus; they were responsible for the form of behaviour founded on another trio of canting clichés: the good, the beautiful, and the true. They had served for centuries as the basis of schools of humbug, unscientific philosophies. A mere vocal question mark will suffice to cancel them. But let us just once more, before we finally abandon it and pass on to the discussion of relative realities, repeat this litany of nonsense, by which the minds of millions of men, for thousands of years, had been lulled into stupor’ — with outstretched finger he beat time, as in mocking voice he repeated the incantation, ‘Faith, hope, and charity; the true, the beautiful, and the good’; then dismissed it with a contemptuous rap of the thumb.

‘One day Mensch received the commission to translate a number of English, German, Dutch and French scientific works for a Russian university. These were chiefly standard books concerned with the biological sciences. And suddenly he found the eyes of his imagination looking into the laboratories where experiment and observation were unremittingly pursued. Experiment and observation here at last were two definite concepts to be introduced into a mind emptied of all the lumber of cant. He saw them as Renan before him had seen them as two illimitable lines, railroads, on which a vast train, loaded with eager adventurers and intrepid explorers, moved forward. Sometimes with dazzling speed — sometimes at a snail’s crawl; but it moved always. Its progress might be delayed, but it was never stopped. On the lines of experiment and observation a few men were always going forward, well in advance of the bulk of humanity, towards the realms of knowledge. Many came back empty-handed; some brought no more than news of a light which belonged to the future; others found a clue, slight in itself, but pointing to many tracks; and to a rare individual it fell from time to time to make a supreme discovery.

‘But at whatever pace the majority of these men advanced, and however far they went, their progress was only in one direction. Despite all they had learnt, and their prodigious facilities for assimilating knowledge, they remained in general ordinary men, brilliant specialists within a small compass, but in character no more developed thanthe majority. Their judgment, save when it was applied to a concrete scientific problem, was as warped as that of their contemporaries; they fell as easily as any others into the traps laid by the politicians and the theologians; often they helped to make those traps. They too were victims of prejudice, mean-minded and narrow-gutted. Self-deception ruled their minds; self-dissection they could not or would not apply.

‘The financiers behind the leading political juntas had therefore plenty of scientific material at their behest. The leaders of the nations found no chemist or physicist unresponsive to their orders, and the result of this docility became for the first time strikingly obvious in the war of 1914–1918, the first chemical war on a fairly large scale.

‘That war gave a few people an inkling of what might follow. The lay mind made no attempt to understand the scientific mind, but it became suspicious and frightened of the possible passing of power into the hands of the scientists. For the first time the uneducated thousands were warned, chiefly in the Press, that an entirely new menace might be threatening them.

‘In its appointed hour the vision of Mensch broke into flower. For a number of years he had thought the scientific man to be the perfection of human evolution. This type of man had gone ahead and found, not vague theories to dwindle into emptiness at the first attempt at practical application, but the two great principles of experiment and observation. A prophetic artist was needed to realize that these two great principles could be applied to the solution of all human problems; that religion with its faith and fear was an appanage of mental savagery; that philosophy with its ethical wranglings was an even more futile attempt to escape from man’s self-imposed burdens; but that all their shams could be broken up, their stranglehold on the mind destroyed, by the vigilant application of these two guiding rules.

‘Mensch was that prophetic artist. Once that vision had taken form in his mind, he set out to examine it in detail. It seemed to him logically certain that no deviation from the ancient routine of battle and recuperation, of senseless slaughter and useless recovery, was to be expected, so long as the old laws of thought prevailed; it seemed equally clear that the control of humanity had passed from the theologians to the politicians, and must in due course pass from them to the scientists. Yet it was plain that the scientific point of view did not exist apart from specialization. In the groups and sub-groups of the specialists there were but a handful of first-rate minds; there were thousands of mediocrities and hundreds who were definitely dangerous, either gullible or corruptible to the end of their time.

‘He concentrated now exclusively on the translation of scientific works, in order that he might move constantly among their users. Here and there he found a man such as we now term fully developed up to the present pitch; one who was guided in his self-conscious dealing by the principles of experiment and observation. It was a memorable day for him when he met the physiologist M’Grath, who used his own body for the purposes of experiment.

‘The passionate capacities his thoughts did not absorb were concentrated into love of little children. Here he followed and was content to follow a charming precedent. The little children suffered him to come unto them, and he sought their company. Wherever he might happen to be his temporary home consisted of one room in a mean city street, wherein all day long and far into the evening the urchins frolicked and fought. Often he would lay down his pen and go to them, teaching them new games, telling them of alien children in far lands, playing a tune on his fiddle that they might dance, or impersonating grotesque and comical beasts to draw their laughter. His dramatic instincts found their complete gratification in the mothering and fathering of the unwanted. He never begot a child himself. Not only promiscuous breeding, but unintelligent motherhood, outraged his sense and disgusted his senses. The necessity of establishing motherhood on a vocational basis was one of his earliest decisions.

‘He began to collect infants when he realized that he would one day require disciples. He chose them with discrimination, noting the necessity that the material for his educational experiment should be physically hardy and mentally endowed. He never took a child of less than three years of age or more than five, with rare exceptions. His ambition was to select one boy from each European nation, to transport them to an estate far from all human settlements, and there to prepare them for their mission.

He first chose St. John Richmond and thereafter Conrad Pushkin. In order to provide for these two he whittled down his, and their, needs to the finest point; he worked from eight o’clock each night until four each morning, allowed himself four hours for sleep, and devoted the remainder of the day entirely to their development. At the end of five years he had adopted three boys, having added Carl Winburg to the establishment. He foresaw that his resources would not permit him to do these three justice if he added to their number, but happily just then the legacy of the Dingwall millions befell him. Some years before, the remarkable inventor of the Dingwall car had met Mensch in a Viennese café, where they had talked a night through. Dawn separated them, and the little Jew’s reluctance to ally himself with a man of money kept them apart. But Dingwall on his death-bed had forced his millions on the friend of that night. “He shall have his chance to fight with all they imply,” thought Dingwall with amusement as he struggled with death, for struggle was his natural medium of self-expression, and he could no more die than live passively. “Let him see what he makes of them.” I regret that Dingwall is unable to witness’ — Antoine smiled gently and swept his arm slowly towards his auditors — ‘the result.

‘Dingwall knew nothing of the child collection, or he might have been robbed of his satisfaction. The motive behind that legacy was friendly malice. It would have been cheated. Mensch, like other Jews in the wilderness, embraced the manna with praise and benedictions. Within the shortest possible time he was established with his disciples, to whose number each year added, in his isolated citadel, and his educational experiment was in full swing. The Menschlein, as he lovingly called them, had no gods and no parents; they grew up ignorant of all enslaving herd codes of the outer world; Mensch, sweeping away from them the accumulated spiritual rubbish-heaps of centuries of false thought, taught them the true meaning of words. As they grew older he led them back to the ancient Greek fountain-head of science. “The honeyed spirit of those old Greek sages still brooded over them.”

‘From its inception, Nucleus was a self-governing community, in which reigned a complete anarchy which later had to a large degree to be abandoned, but which will certainly become universal again as soon as the race has been educated up to it.

‘Only the most imaginative of you here can possibly guess with what sense of power those boys presently went into the world to teach. The younger ones among you, who have as a matter of course received a similar education to theirs, can barely conceive what it meant at that time, in those political and social conditions, to be a man without fear; a man balancing a healthy body on firmly planted feet, and possessing a brain which could cut with knife-like precision through the common perplexities and doubts of common men. Hemmed in by mental inhibitions impenetrable as barbed-wire entanglements, overloaded with chimerical responsibilities — thus men lived long after the dawn of the twentieth century. Although in the seventeenth Descartes had declared, “Cogito, ergo sum,” many of them could read and write, but to think, as we understand thought, was impossible to most of them. “In the beginning was the word” — small wonder that those who believed that did not inquire whether it might have been a catchword.

‘It was inevitable that each of these powerful young men quickly gained adherents and followers, but they were careful to admit to their intimacy only those capable of thought on experimental and searching lines. They took care to be considered by those who might have become their enemies had they taken them seriously, mere theorists. They kept in constant touch with one another and with Mensch himself, and presently they spread like a human cable, linking up every important centre of experiment and research in the world. In a far shorter time than even he had foreseen, their teacher had formed a phalanx of men sufficiently numerous and sufficiently powerful to step into the high places when the moment should call them.

‘So we come to the last war; the war of unbounded destruction predicted by a few seers even in the early nineteen-twenties; the reductio ad absurdum of the tug-of-war by competitive nationalists, who hitched each his wagon to a star of malevolence, and piled it to the brim with the engines of destruction and annihilation furnished by their prostituted “scientists.”

‘Mensch, watching at a distance, would have been content to wait. The eruption he had so long ago foreseen did not attract him to close inspection; to attempt to expedite or to stay its progress was not his concern. Most human life, of the quality then being cancelled, did not call to him for rescue. Human life — the cantmongers for centuries had been satisfied to extol its sanctity and to encourage its wasting and rotting by the slow disintegration of disease and death. The swifter process was the cleaner. Let the flames leap and lick, and the gases stifle and strangle.

‘But where Mensch could wait, his men could not. Their opportunity was at hand. The holocaust needed guidance and encouragement if it were to sweep in the desired direction. They would need men hereafter; or rather, the raw human material from which might begin to be fashioned the ultimately desired human being. The undermen, untainted by the subversions of the tottering civilization the offspring they would produce were fit to form the bedrock of the new erection. But the tainted, the intelligent savages whose instincts had been trained and sharpened towards this end, whose competitive rabies had reached its climax, must go. They went.

‘Thus the battle resolved itself into a straight fight between madmen armed with science, and sane men, compelled to strike them down with the same weapon. While nation had armed against nation, within each had waited the prepared members of another company. Whilst the remnants of armies struck blindly and blunderingly at one another, the soldiers of science looked beyond them, and struck fully and finally at those behind them.

‘Mensch was already superseded by the striplings he had reared. The teacher’s mission was over; that of the pupils would now begin. We know that it is the experiment which matters and that its result is seldom final; how much his experiment mattered it is for us, his heirs and successors, to prove.’

RADIUM AGE PROTO-SF: “Radium Age” is Josh Glenn’s name for the nascent sf genre’s c. 1900–1935 era, a period which saw the discovery of radioactivity, i.e., the revelation that matter itself is constantly in movement — a fitting metaphor for the first decades of the 20th century, during which old scientific, religious, political, and social certainties were shattered. More info here.

SERIALIZED BY HILOBOOKS: James Parker’s Cocky the Fox | Annalee Newitz’s “The Great Oxygen Race” | Matthew Battles’s “Imago” | & many more original and reissued novels and stories.