RADIUM AGE ART (1919)

By:

July 15, 2024

A series of notes regarding proto sf-adjacent artwork created during the sf genre’s emergent Radium Age (1900–1935). Very much a work-in-progress. Curation and categorization by Josh Glenn, whose notes are rough-and-ready — and in some cases, no doubt, improperly attributed. Also see these series: RADIUM AGE TIMELINE and RADIUM AGE POETRY.

RADIUM AGE ART: 1900 | 1901 | 1902 | 1903 | 1904 | 1905 | 1906 | 1907 | 1908 | 1909 | 1910 | 1911 | 1912 | 1913 | 1914 | 1915 | 1916 | 1917 | 1918 | 1919 | 1920 | 1921 | 1922 | 1923 | 1924 | 1925 | 1926 | 1927 | 1928 | 1929 | 1930 | 1931 | 1932 | 1933 | 1934 | 1935 | THEMATIC INDEX.

According to HILOBROW’s periodization scheme, the years 1918–1919 are the apex of the cultural decade known as the Teens (1914–1923).

“What has Curie or Mme. Curie achieved? Radium? — thank you.”

— William Carlos Williams, from a speech on poetry reprinted in the magazine Poetry (July 1919, “After-the-War Number”).

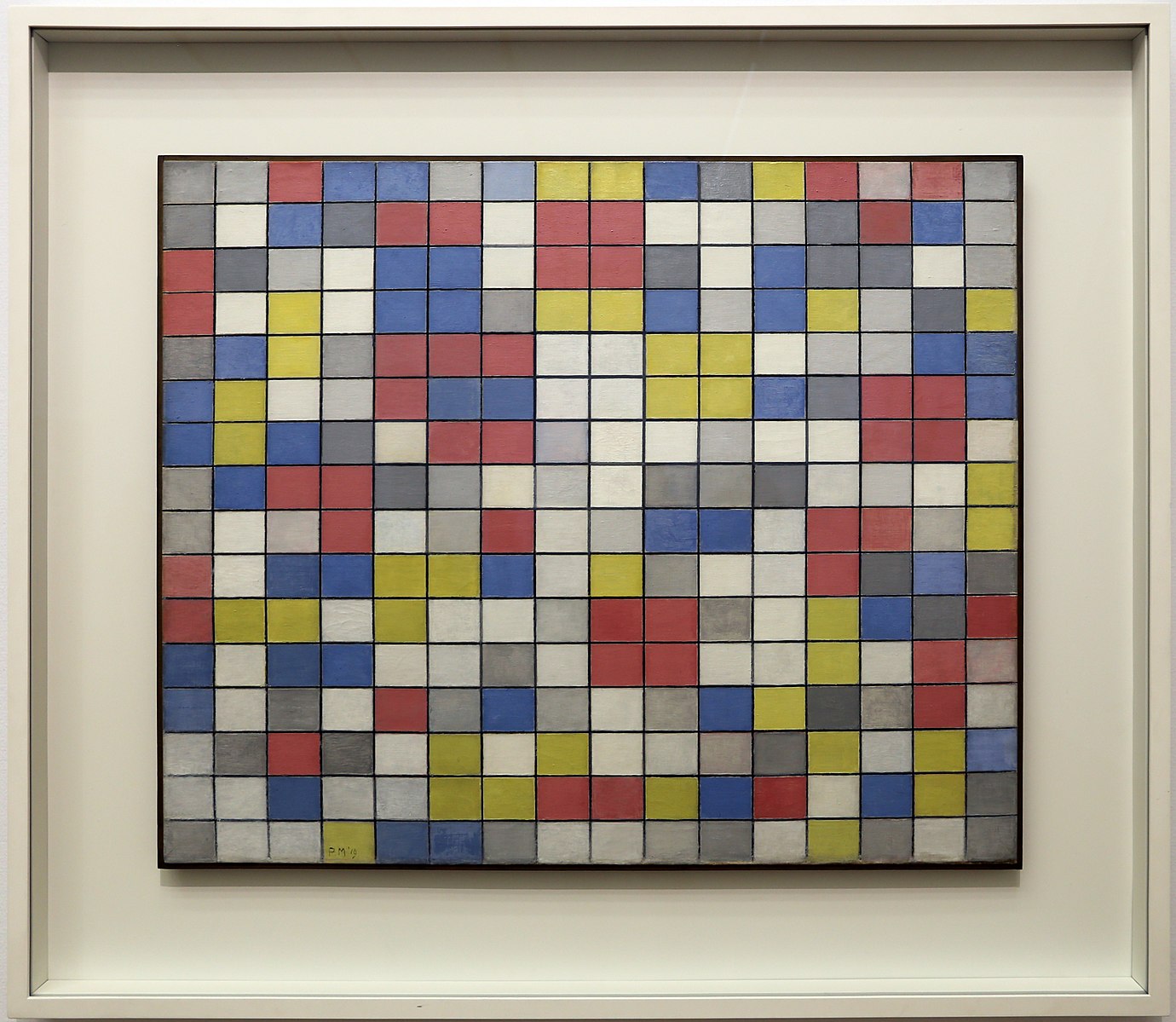

Piet Mondrian, in Paris, begins painting his grid-based compositions (Neo-Plasticism). Mondrian in 1919: Life is becoming “more and more abstract… Modern man exhibits a changed consciousness: today, every expression of his life has a different aspect, an aspect more positively abstract.” So, inevitably with art: as a purified representation of men’s minds it would henceforth express itself in an “aesthetically purified, that is to say abstract, form.”

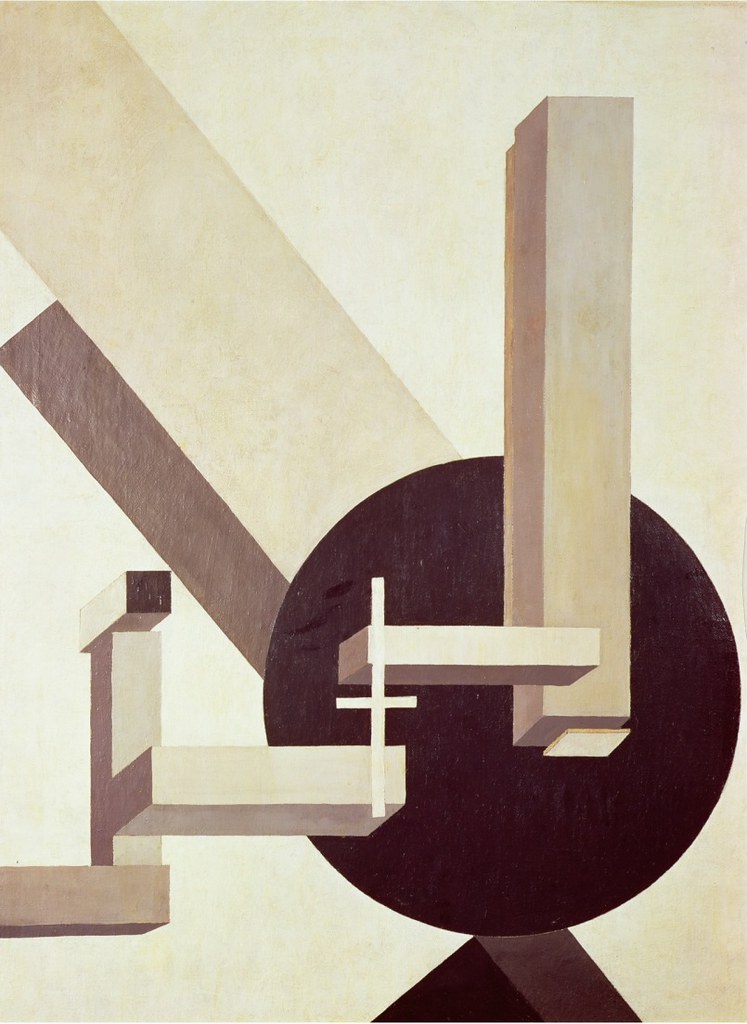

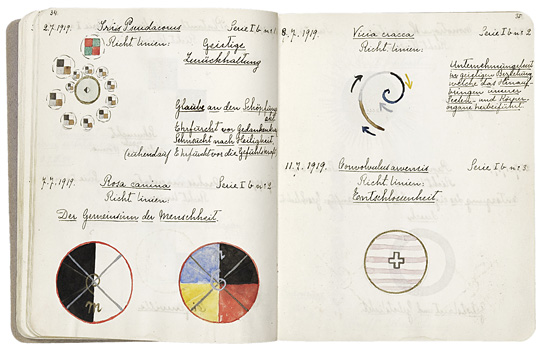

From MoMA’s website: “Between 1919 and 1927 El Lissitzky produced a large body of paintings, prints, and drawings that he referred to by the word Proun (pronounced pro-oon), an acronym for “project for the affirmation of the new” in Russian. […] Lissitzky’s radical reconception of space and material is a metaphor for and visualization of the fundamental transformations in society that he thought would result from the Russian Revolution.”

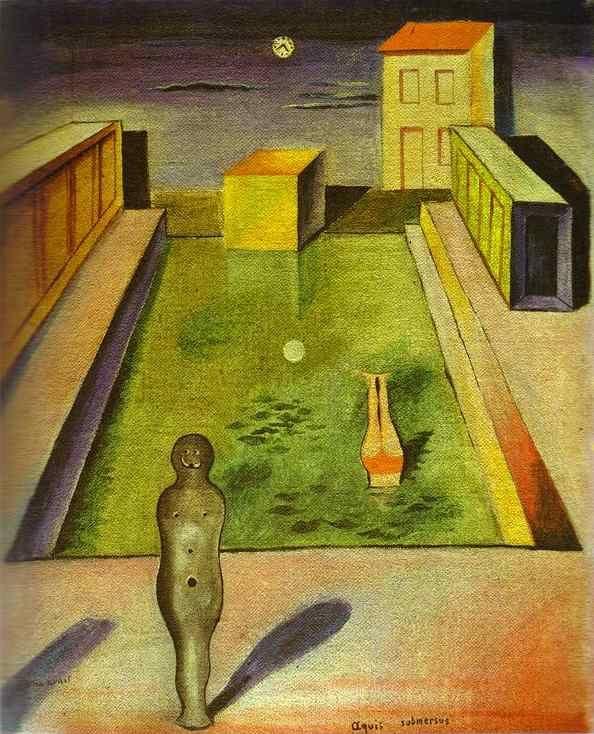

De Chirico’s work after 1919 became much more based in reality and far more traditional. This later work was less colorful, less symbolic, less powerful and way more mundane. It is definitely the work from the earlier Metaphysical period that defines him as the artist as we know him today.

El Lissitzky was among the artists who were most firmly committed to the Great Experiment and one of the most multifaceted and cosmopolitan of revolutionary Russia. He was steered towards abstract art by the influence of Malevich’s Suprematist ideas, which he soon abandoned as he found them excessively mystic. Towards 1919 his wish to integrate painting and architecture led him to create his first Proun pictures, works with a markedly geometric character which constitute his chief contribution to the art world.

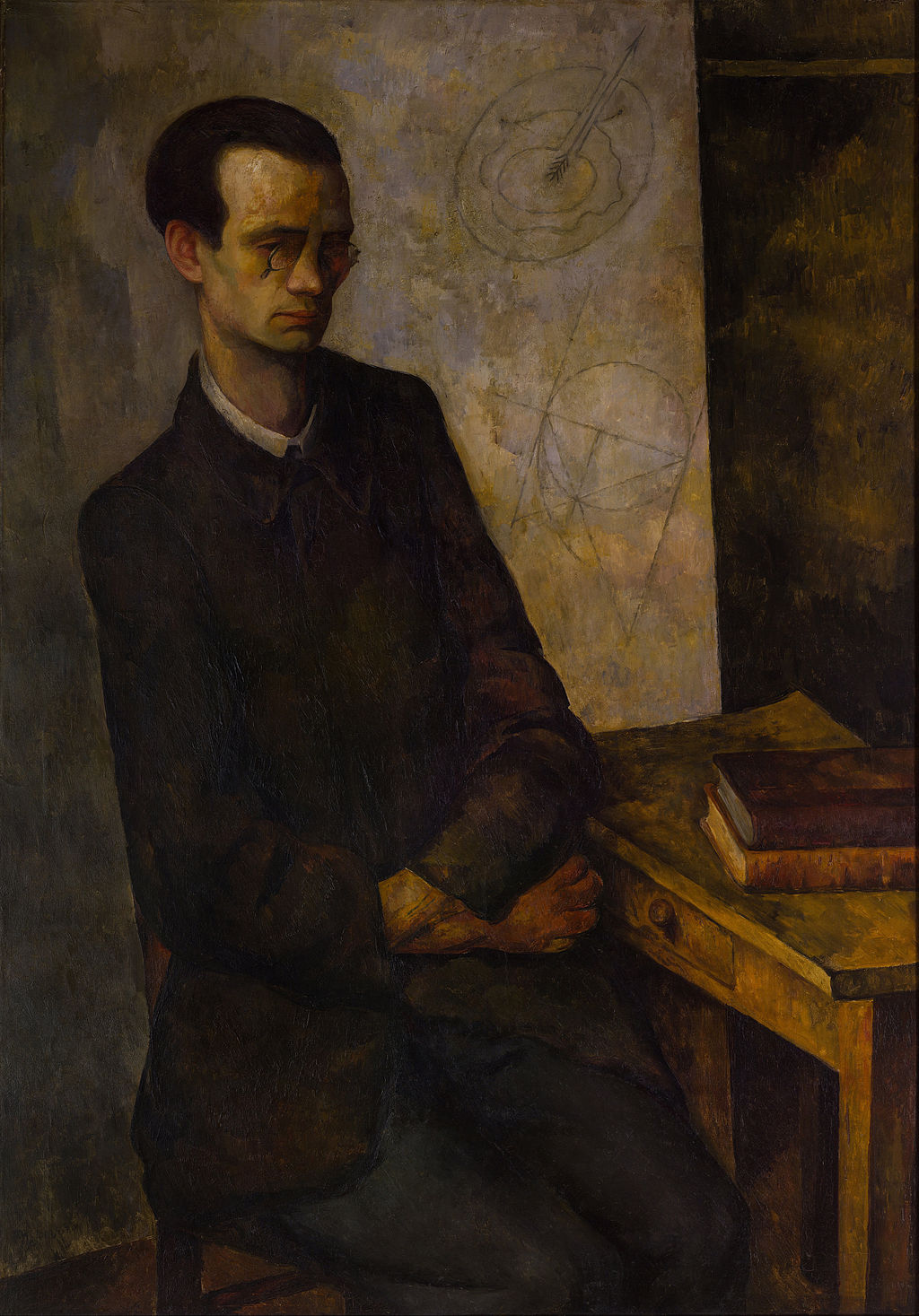

The most celebrated citadel of avant-garde design to be established in Europe in the period between the two world wars — the Bauhaus, founded by the architect Walter Gropius in Weimar in 1919 — initially billed itself as the “Cathedral of Socialism.” The school became famous for its approach to design, which attempted to unify the principles of mass production with individual artistic vision and strove to combine aesthetics with everyday function. Staff at the Bauhaus included prominent artists such as Paul Klee, Wassily Kandinsky, and László Moholy-Nagy at various points. The radicalism of the Bauhaus was in practice a more volatile and bizarre amalgam of artistic, mystical, and collectivist ideas than its socialist reputation suggests. “Its ranks were rife with the followers of occult sects, bohemian lifestyles, food cults, and sundry other manifestations of a freewheeling counterculture.” — Hilton Kramer

Kandinsky in 1919’s “On New Systems in Art”: His abstract paintings express a new, industrialized mode of consciousness, and a “new transfigured world of iron.”

Les Champs Magnétiques, the first book produced using the techniques of surrealist automatism, is written by André Breton and Philippe Soupault.

Einstein and Minkowski’s theories reach the general public after being validated by Eddington’s observation of a 1919 solar eclipse. Karl Popper would later claim to have formulated his initial ideas about “the demarcation problem” — how should we distinguish science from pseudoscience? — after he learned about the British expedition to study the solar eclipse. The 17-year-old Popper was struck by the risk Einstein proved willing to run in proposing a falsifiable, refutable, testable theory about starlight’s curvature during a solar eclipse. If Eddington and Dyson’s experiment hadn’t confirmed his theory, then Einstein would have been forced to abandon it.

Sigmund Freud’s 1919 essay “Das Unheimliche.” The Uncanny is what unconsciously reminds us of our own Id, our forbidden and thus repressed impulses. We project our own repressed impulses onto certain objects — dolls, for example — which then become an uncanny threat. (This concept is closely related to Julia Kristeva’s concept of abjection, where one reacts adversely to something forcefully cast out of the symbolic order.)

Rutherford demonstrates that the atom is not the final building block of the universe.

Browning and Thompson finalize design of their machine guns.

Mussolini founds Fasci del Combattimento; Third International founded at Moscow.

Charles Fort’s Book of the Damned.

Also see: RADIUM AGE: 1919.

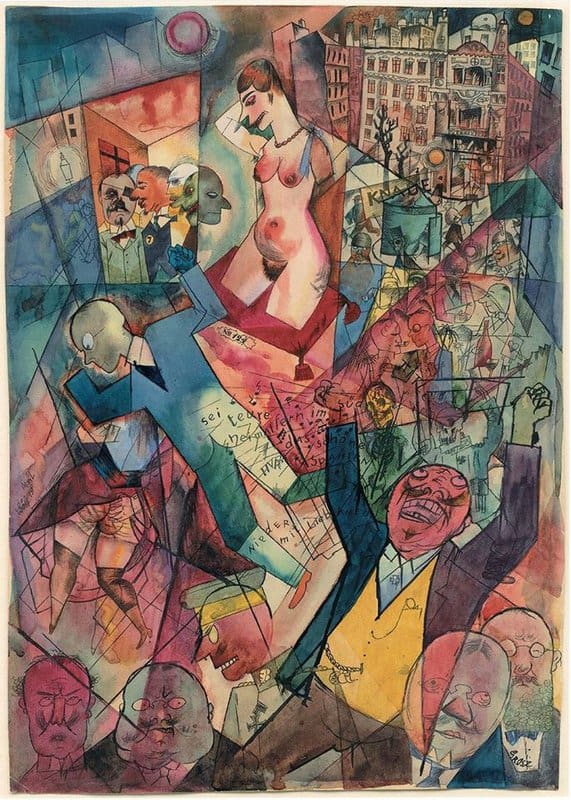

Max Beckmann enlisted in the German army during World War I. Initially, like many Neue Sachlichkeit and Futurist artists, Beckmann believed war could cleanse the individual and society. After experiencing the widespread destruction and horror of the war, however, he became disillusioned with war and rejected the supposed glory of military service. The Night‘s illogical composition relays post-war disillusionment and the artist’s confusion over the “society he saw descending into madness.”

Nash knew the area well from the spring of 1917, when he served in the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) on the Western Front and from later that year, when he returned to the war zone as an official war artist.

Wood, metal, cods, cardboard, wool, wire, leather, and oil om canvas. Schwitters invented a new kind of collage assembled from the detritus of everyday life he called it “Merz.” Pepe Karmel suggests that although this composition could suggest machinery, the painting’s resemblance to Balla’s “Mercury Passing in Front of the Sun” (1914) suggests that it simultaneously represents the solar system as an orrery-like mechanism.

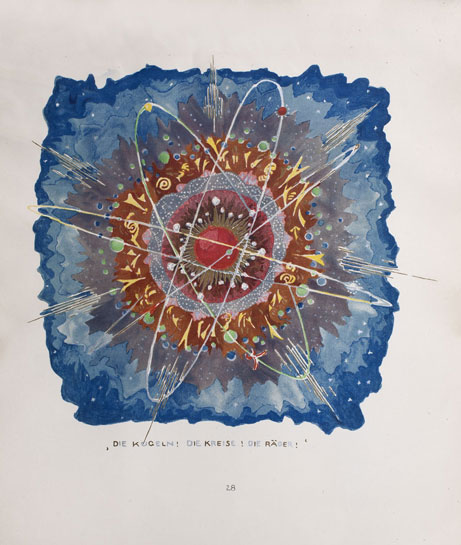

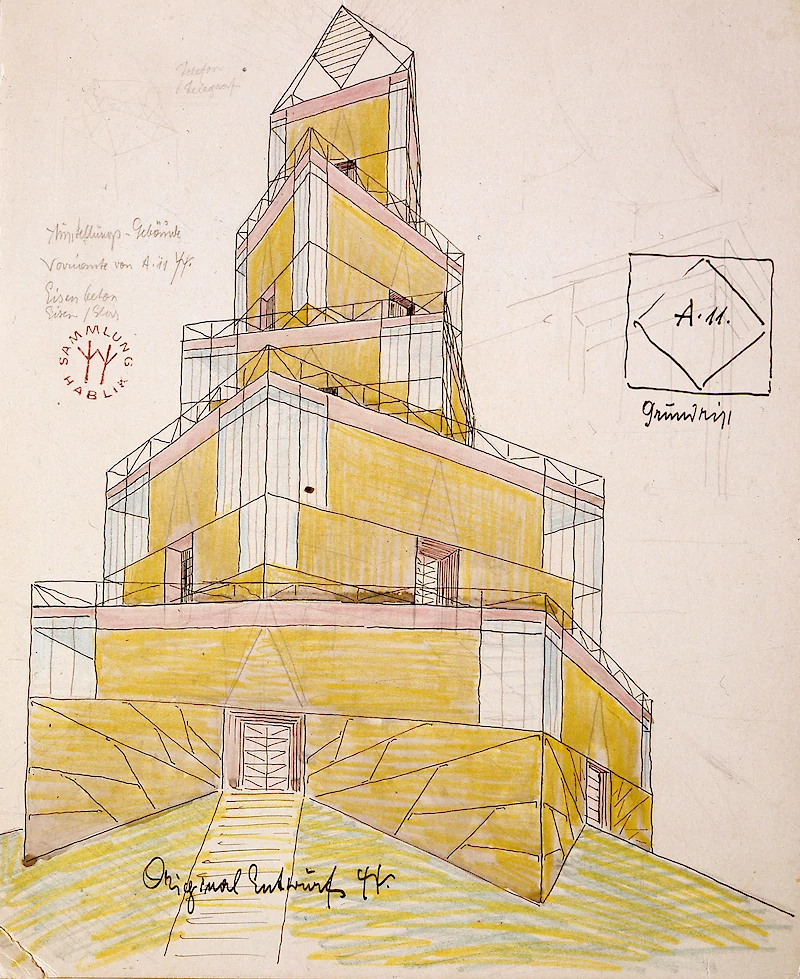

Part four, “Structures of the Earth’s Crust,” moves from the reconstruction of mountain ranges to the reworking of the entire Earth with glass architecture, and expands to Part Five, “Star Structures,” in which stars and other cosmic entities are transformed to crystalline structures. In the last pages, glass architecture seems to implode upon itself, with an illustration of an atom-like structure, with the note: “THE SPHERES! THE CIRCLES! THE WHEELS!”

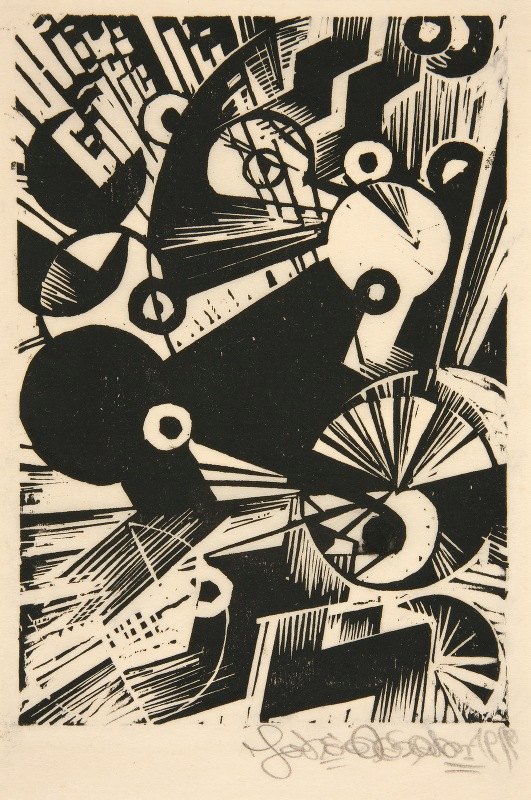

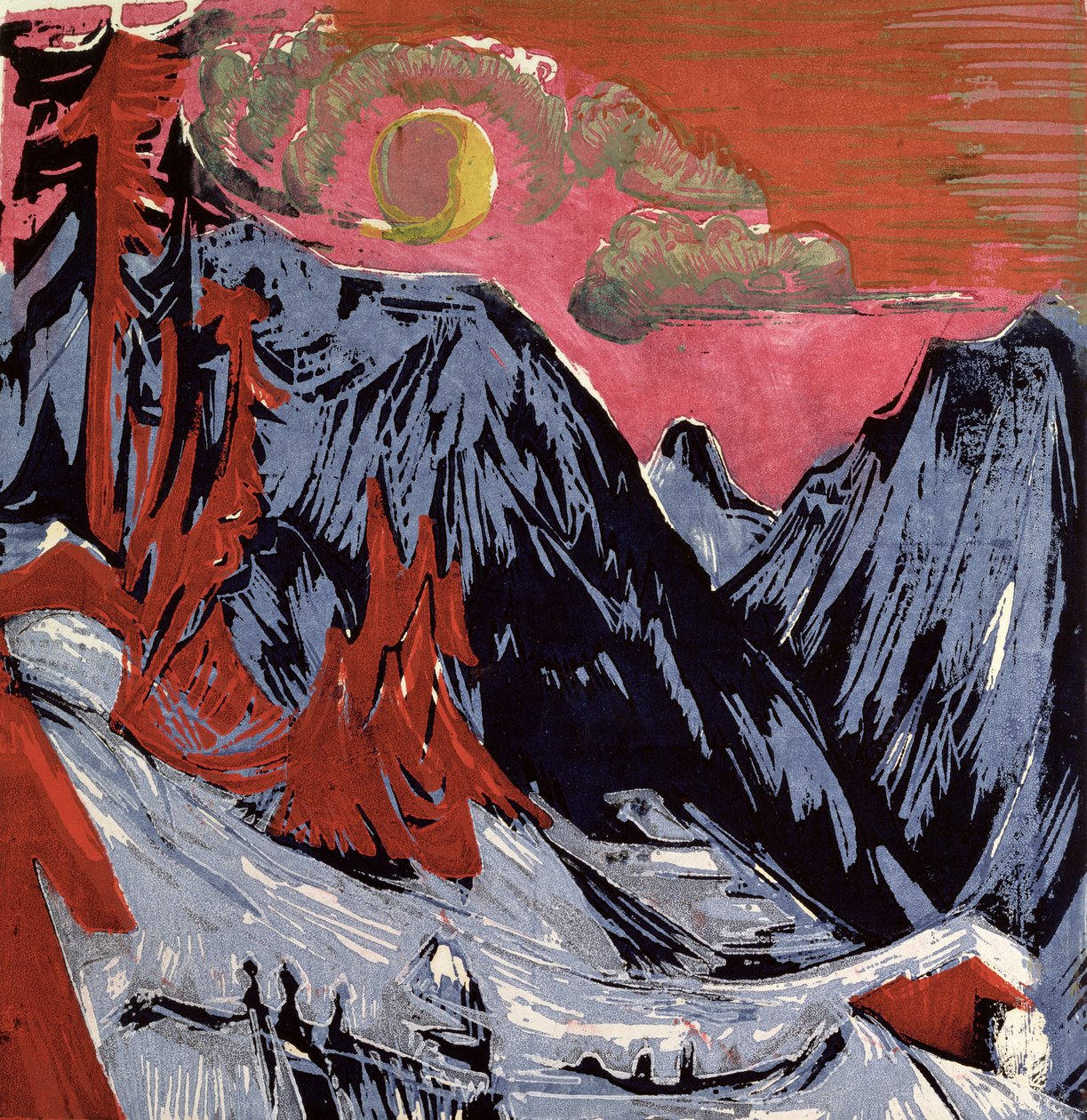

Kirchner’s painting was used to illustrate the cover of a 2014 edition H.P. Lovecraft’s 1936 sf novel At the Mountains of Madness. See below.

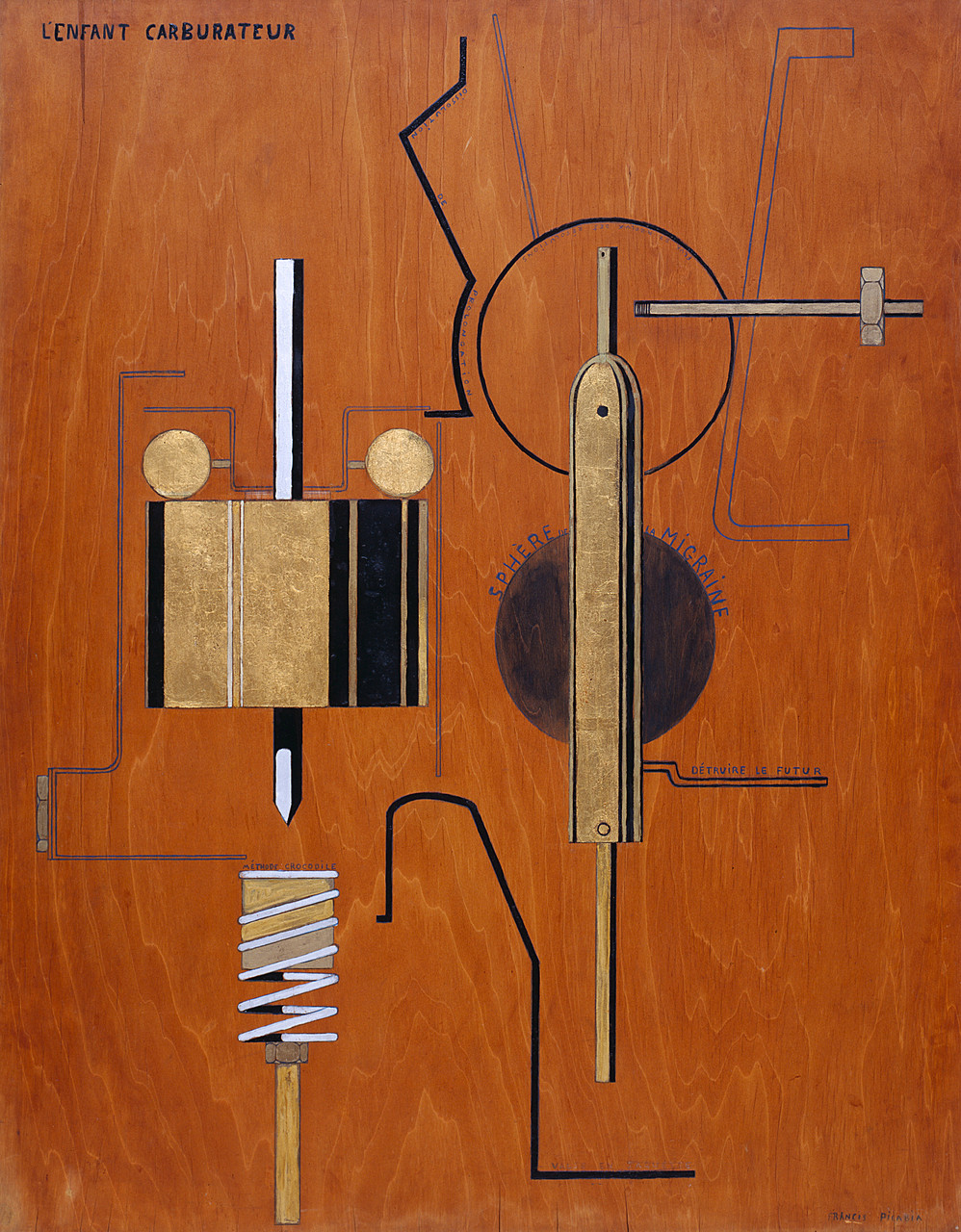

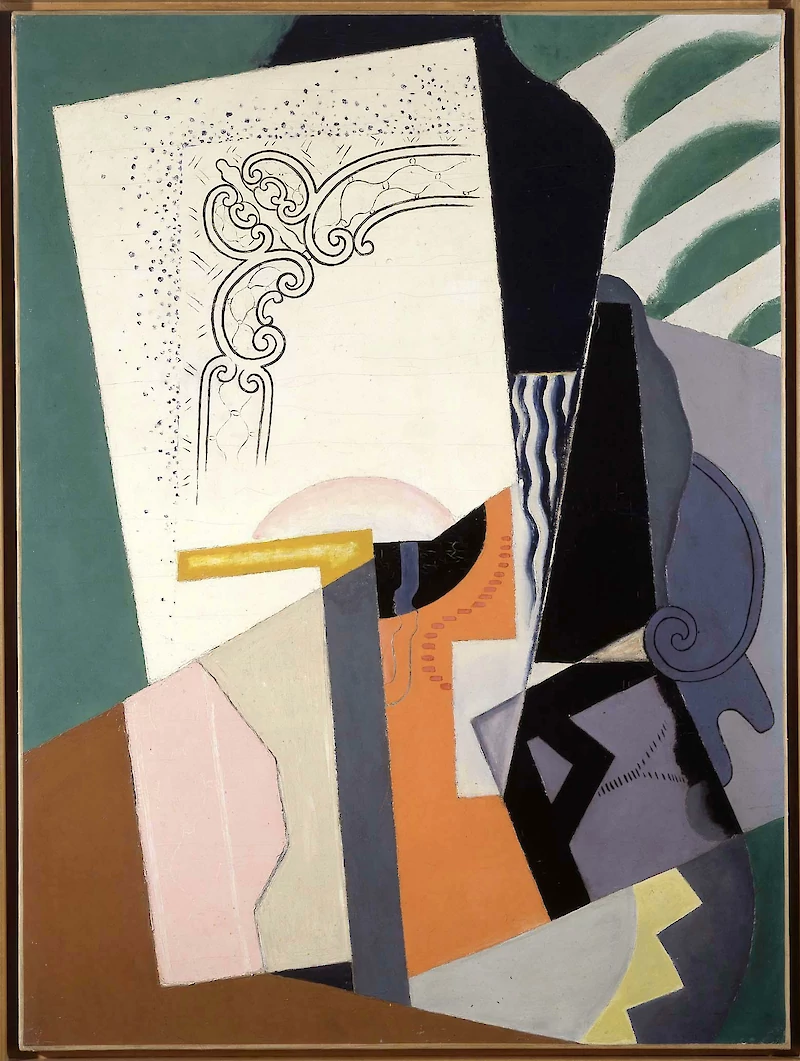

From the Guggenheim’s website: “Francis Picabia abandoned his successful career as a painter of coloristic, amorphous abstraction to devote himself, for a time, to the international Dada movement. A self-styled ‘congenial anarchist,’ Picabia, along with his colleague Marcel Duchamp, brought Dada to the New York art world in 1915, the same year he began making his enigmatic machinist portraits, such as The Child Carburetor, which had an immediate and lasting effect on American art. The Child Carburetor is based on an engineer’s diagram of a “Racing Claudel” carburetor, but the descriptive labels that identify its various mechanical elements establish a correspondence between machines and human bodies; the composition suggests two sets of male and female genitals. Considered within the context created by Duchamp’s contemporaneous work The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even (1915–23), as art historian William Camfield has observed, The Child Carburetor, with its “bride” that is a kind of “motor” operated by “love gasoline,” also becomes a love machine. Its forms and inscriptions abound in sexual analogies, but because the mechanical elements are nonoperative or ‘impotent,’ the sexual act is not consummated. Whether the implication can be drawn that procreation is an incidental consequence of sexual pleasure, or simply that this ‘child’ machine has not yet sufficiently matured to its full potential, remains unclear. Picabia stressed the psychological possibilities of machines as metaphors for human sexuality, but he refused to explicate them. Beneath the humor of his witty pictograms and comic references to copulating anthropomorphic machines lies the suggestion of a critique — always formulated in a punning fashion — directed against the infallibility of science and the certainty of technological progress.”

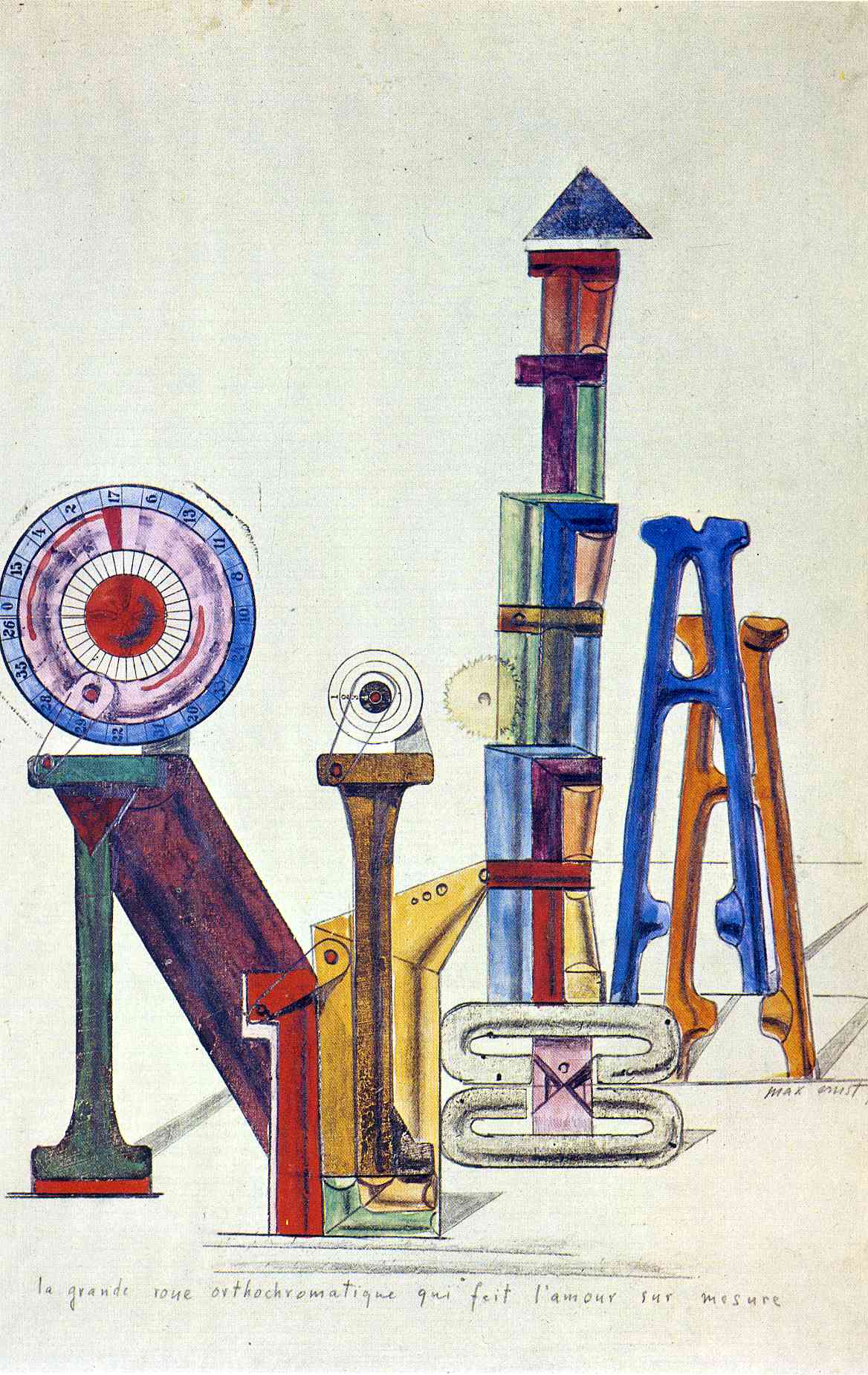

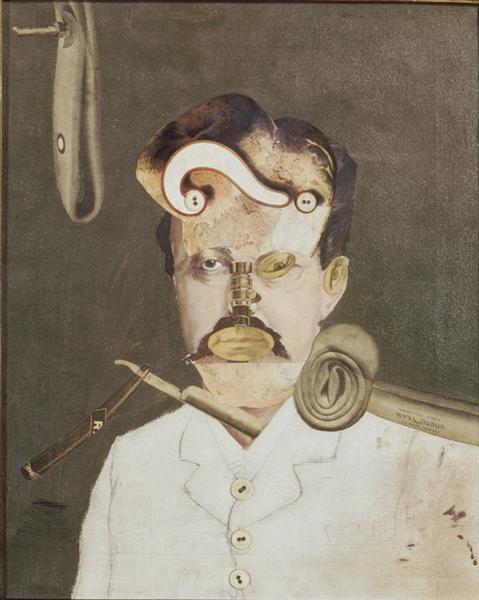

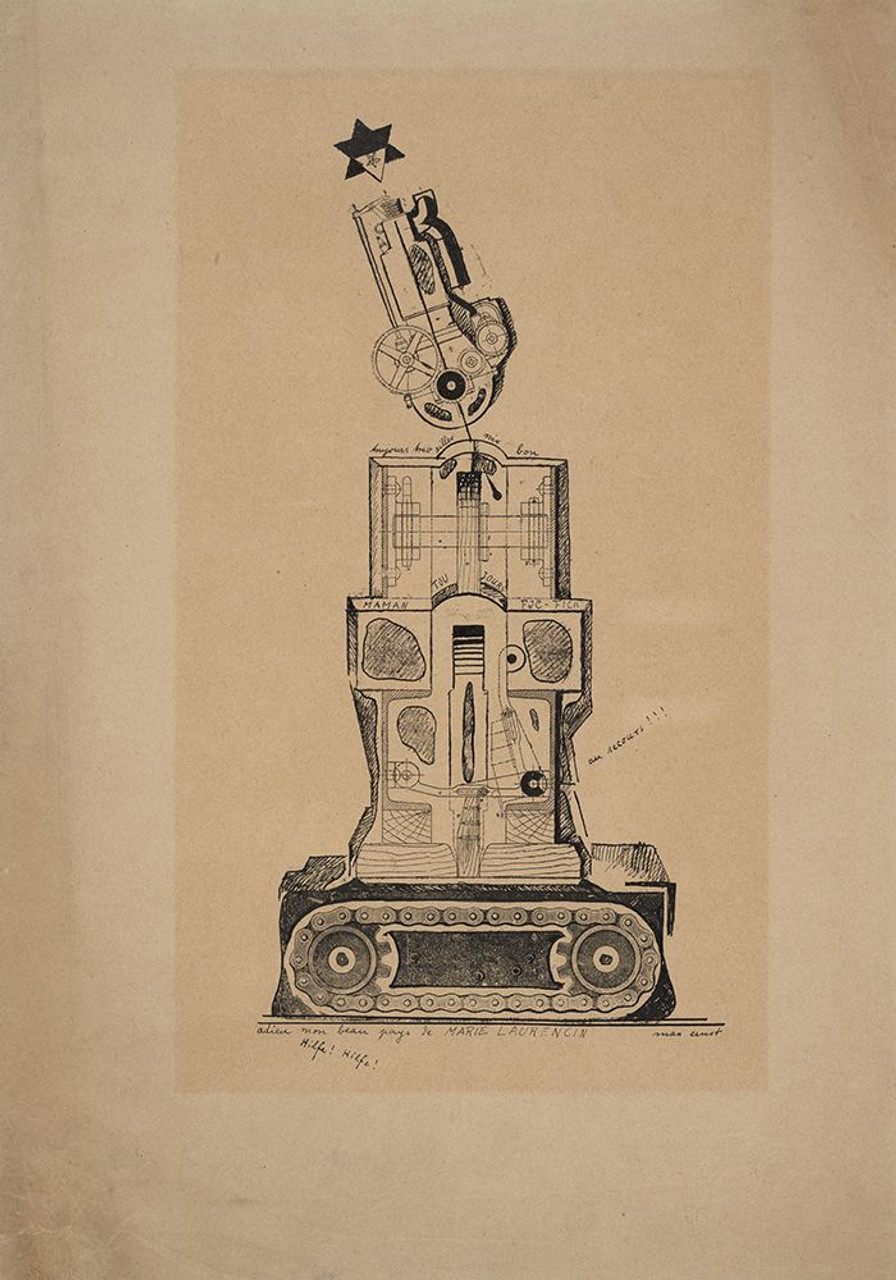

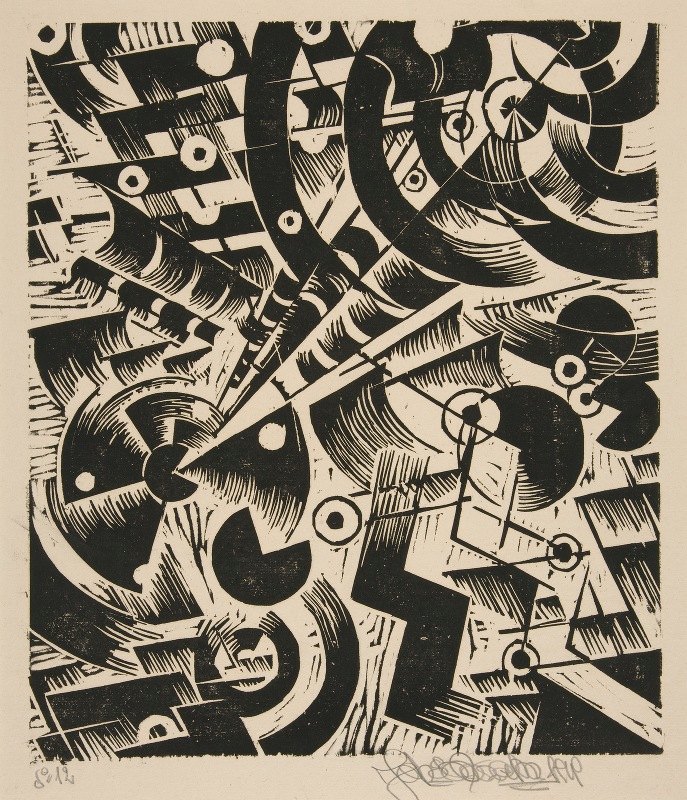

From MoMA’s website: “From 1919 to 1920, Ernst created a series of works by printing, stamping, tracing, or taking rubbings from metal plates or type. These printing tools were borrowed from a commercial press. Ernst arranged the plates, frequently turning and reusing the same block and adding connecting lines with pen and ink to produce images of anthropomorphic machines. Rather than evoking dependable technological power, the pseudo-machine depicted in this work seems precarious at best.”

Influenced by the Italian metaphysical art it is one of Ernst’s earliest works showing surrealistic accents.

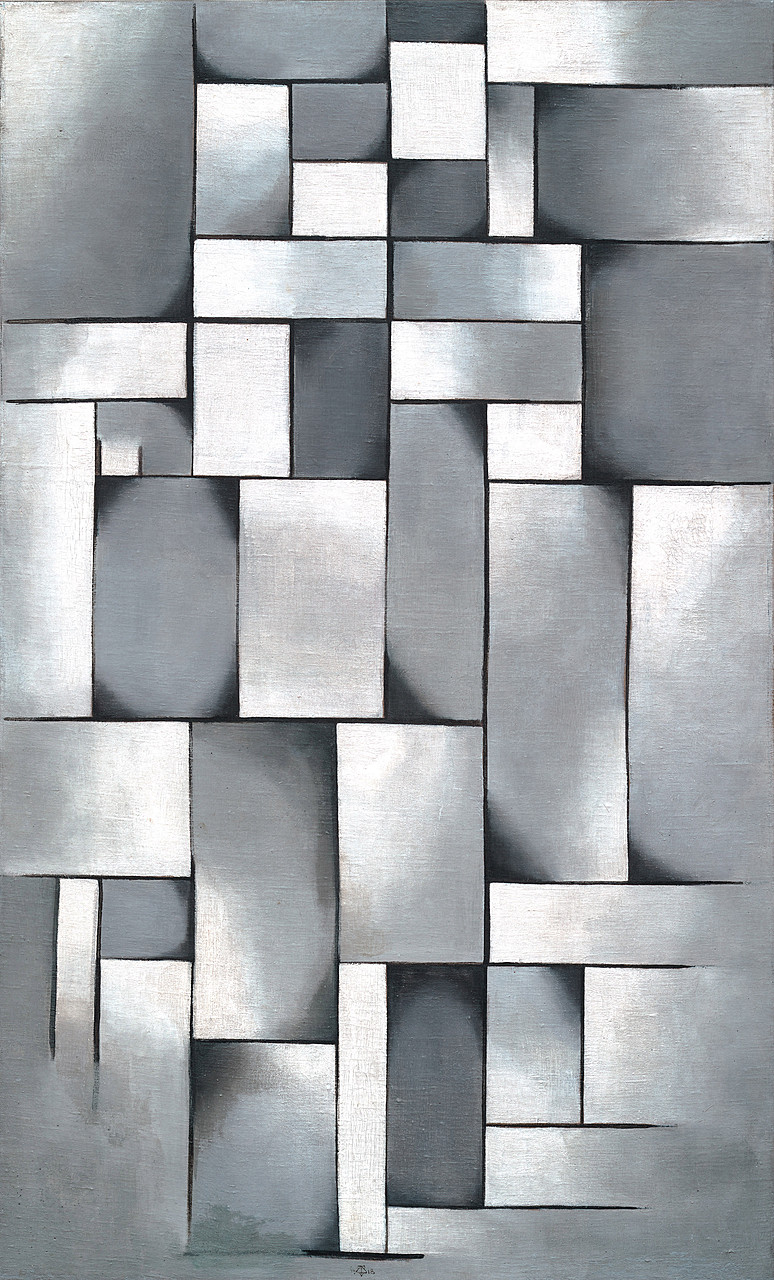

From the Guggenheim’s website: “In his painting van Doesburg followed Mondrian’s example by systematically divesting his imagery of figurative references and reducing pictorial elements to colors and geometric forms in oppositional relationships. In so doing, he hoped to express a universal reality underlying the capriciously changeable appearances of nature.”

The syncopated character of modern jazz dances is expressed here by the rigid orthogonals of geometric abstraction — which, as Mondrian argues in his 1917–18 essay “The New Plastic in Painting,” are about “tensing” (dynamic tension) and the search for equilibrium. The side-by-side vertical bands suggest two vertical dancers’ bodies pressed together; their heads, also touching, become a cluster of small rectangles.

Mondrian — the great diagrammer — insisted that only vertical and horizontal lines were permissible in abstract art. When Van Doesburg made explicit (in the 1925 painting “Counter-Composition XIV”) the diagonal axes implied in the painting shown here, Mondrian resigned from the editorial board of their journal De Stijl and wouldn’t speak with Van Doesburg for two years.

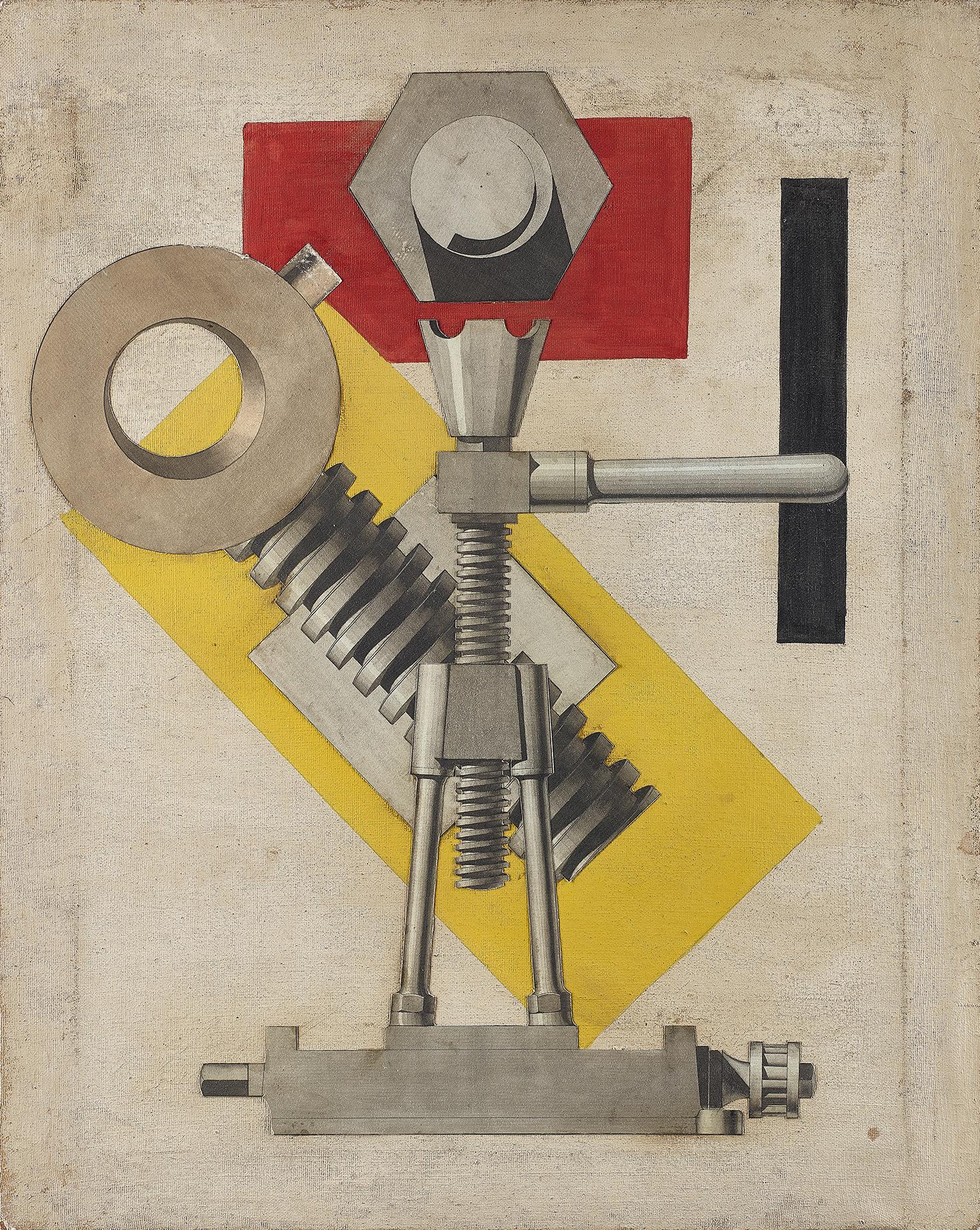

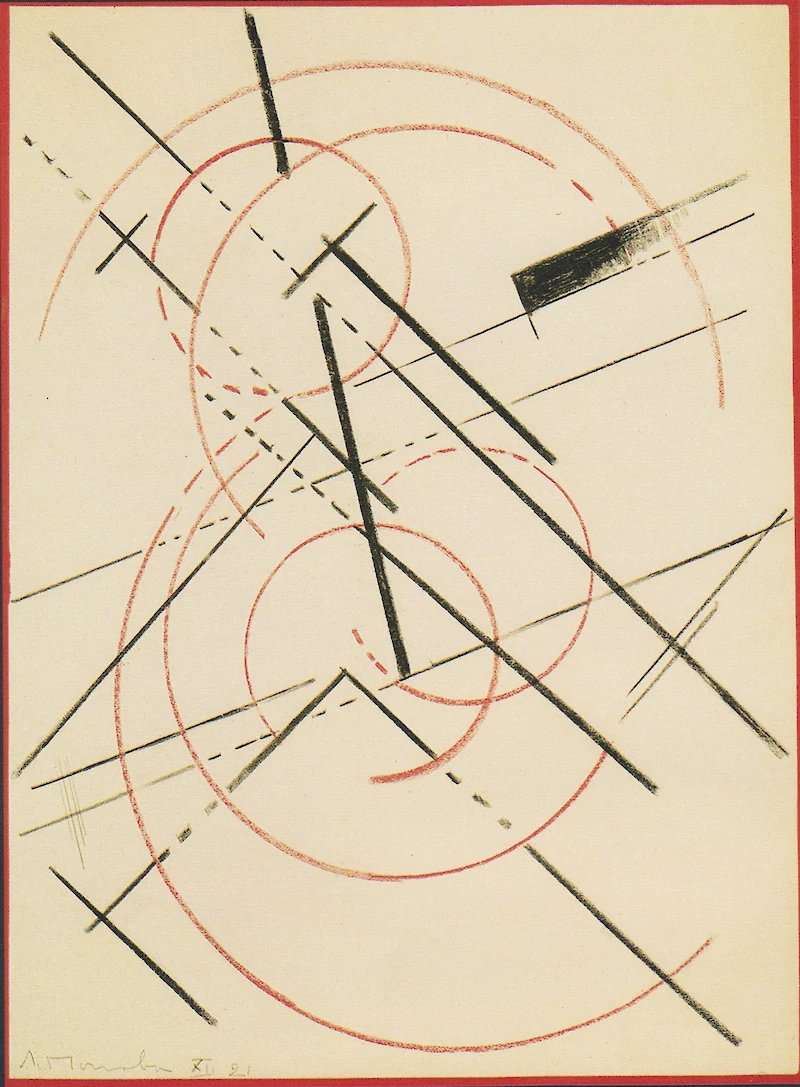

Construction no. 95 (1919)

Construction No.95 was painted while Rodchenko and his wife Varvava Stepanova (also included in auction) were sharing a house with Wassily Kandinsky in Moscow. Working in the afterglow of the revolutions and upheavals of 1917, Rodchenko believed in showing people new ways of seeing to open up new ways of thinking, and that experiments in art and creativity should reflect the transformations taking place in what would soon be the Soviet Union. Taking geometry as his guide, Rodchenko began reducing and separating painting out to a purely elemental level of line, color, form and texture.

First exhibited at the 19th State Exhibition, Construction No.95 was part of his series Linearism, of which there were only 14 paintings — the main body of the series consisted of graphic design works — each a “Construction” with a unique serial number. Rodchenko would later credit the line as his invention and foremost contribution to the development of ideas in contemporary art. The grid was to inform the post-War International Style of graphic design and typography developed by the Swiss School, and reappear as a generative matrix for artistic production in Sol Lewitt’s paintings of the 1960s and beyond.

Dazzle camouflage, also known as razzle dazzle (in the U.S.) or dazzle painting, is a family of ship camouflage that was used extensively in World War I. Unlike other forms of camouflage, the intention of dazzle is not to conceal but to make it difficult to estimate a target’s range, speed, and heading.

The Vorticist Edward Wadsworth, who supervised the camouflaging of over 2,000 ships during WWI, painted a series of canvases of dazzle ships ater the war, based on his wartime work.

Lewis served in the Royal Artillery at the Battle of Passchendaele and could draw from this experience when making the painting.

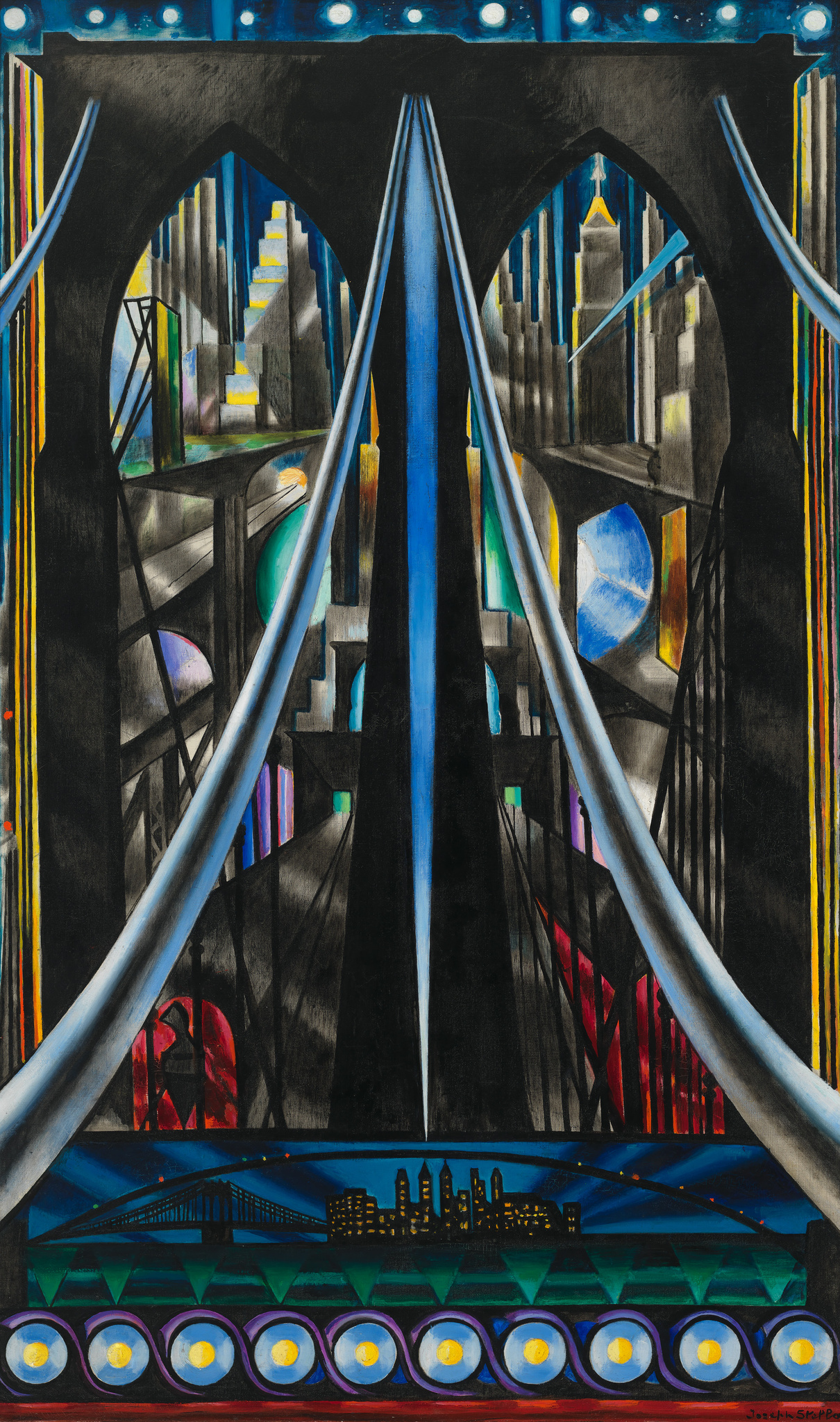

From the Whitney’s website:

To Italian-born Joseph Stella, who immigrated to New York at the age of nineteen, New York City was a nexus of frenetic, form-shattering power. In the engineering marvel of the Brooklyn Bridge, which he first depicted in 1918 and returned to throughout his career, he found a contemporary technological monument that embodied the modern human spirit. Here, Stella portrays the bridge with a linear dynamism borrowed from Italian Futurism. He captures the dizzying height and awesome scale of the bridge from a series of fractured perspectives, combining dramatic views of radiating cables, stone masonry, cityscapes, and night sky. The large scale of the work — it is nearly six feet tall — conjures a Renaissance altar, while the Gothic style of the massive pointed arches evokes medieval churches. By combining contemporary architecture and historical allusions, Stella transformed the Brooklyn Bridge into a twentieth-century symbol of divinity, the quintessence of modern life and the Machine Age.

Stella is a considered a Precisionist.

Elsewhere we read:

Channeling his passion into an obsessive regard for the Brooklyn Bridge, he re-created it as a “towering imperative vision,” alive, as he said, “with the blaze of electricity scattered in lightings down the oblique cables…, the shrine containing all the efforts of the new civilization of America.” Stella’s language was based as much on Walt Whitman’s impulsive rhetoric as on the Futurists’ praise of the Machine Age. Familiar with Futurism since 1912, when members of the movement staged a major exhibition in Paris, where Stella was then living, he painted the Brooklyn Bridge in a variant of that style: he approximated the effects of an automobile moving across the bridge through successive layers of space, while the objects of peripheral vision — the cables and girders — appear at the sides.

From the Guggenheim’s website:

“Landscape (Stadt mit Tieren, ca. 1914–16) similarly represents a synthesis of artistic idioms gleaned from his peers: the pictorial logic invokes a Cubist idiom, while the palette and animal forms recall the paintings of Heinrich Campendonk and Franz Marc. While Landscape predates Ernst’s involvement with Cologne Dada in the late 1910s and the Surrealist movement in the 1920s, the startling juxtapositions and fantastic imagery foreshadow this later work.”

Beat the Whites with the Red Wedge is a 1919 lithographic Bolshevik propaganda poster by El Lissitzky. The intrusive red wedge symbolizes the Bolsheviks, who are penetrating and defeating their opponents, the White movement, during the Russian Civil War.

Also translated as “Ascent and Resting Place.”

Compare with the sun-and-pyramid motif one finds in other mystical art of the period (such as Klint). This painting is an abstract allegory of the soul’s rise towards wisdom. A series of vertical triangles climbs up the center of the canvas, enclosed in a glowing column that signals spiritual illumination. Other triangles overlap to form diamonds marking resting places on the path upwards. Pepe Karmel: “Multi-colored concentric discs explode like small epiphanies.”

The composition is a succession of sequences made up of small rectangles of different colors that finds a moment of comparative rest in the larger rectangles. The ephemeral progression of new events (the small rectangles) is transformed in the larger units into a space of relatively greater duration.

Mondrian: “The unchangeable (the spiritual) is expressed in the composition by means of straight line or planes of non-color (black, white, and gray), while the changeable (the natural) is expressed by means of planes of color and rhythm.”

For Mondrian yellow, red, and blue constitute a “plastic” symbol of the purest and most intense colors in the world. He uses the three primary colors here to express contrast and diversity, and white, black, and gray to produce an equally broad range of variation that appears, however, more homogeneous than the contrasting variation generated with the primary colors.

The human search for unity (be it the idea of a God or the unifying theories of science) is always counterbalanced by the multifarious aspect of nature and by the unforeseeable evolution of life. Checkerboard with Light Colors presents both aspects.

The black and white unity now opens up to the variety of intermediate hues (yellow, red, and blue); the colors of the spirit open up to the three primary colors that symbolize the natural world in the Neoplastic language.

The opening up of black and white to the primary colors will be the guiding motif of Mondrian’s subsequent work, from 1920 up to 1942.

The dynamic and multiform aspect of natural and/or urban space is transformed on the canvas into a whole endowed with greater synthesis and equilibrium before returning to a dynamic state. The canvas serves as a model of space in equilibrium between disharmonies of real space and harmonies of plastic space.

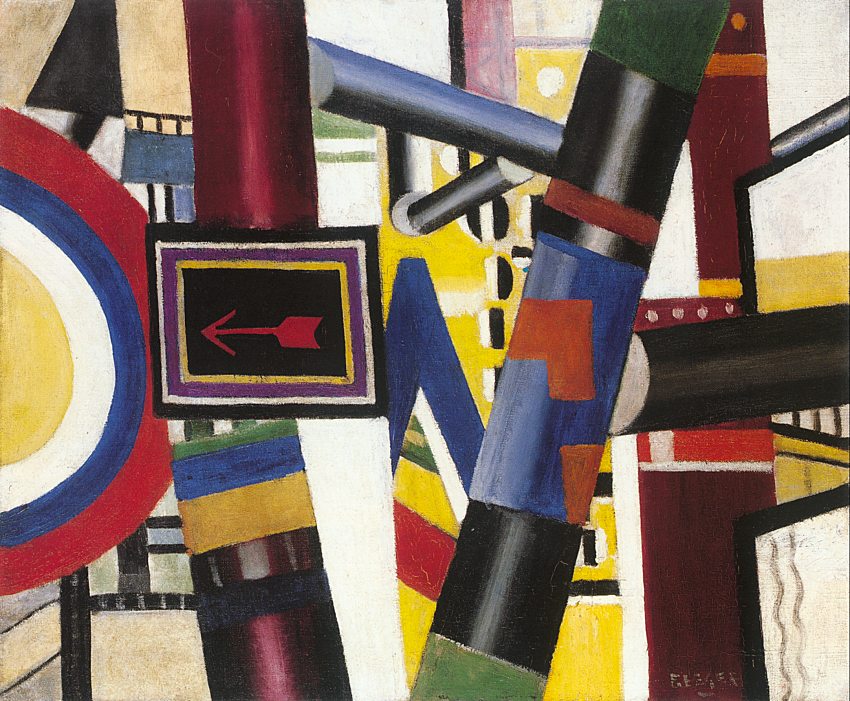

The masterpiece, claims Pepe Karmel, of the genre of abstract paintings depicting the city as a whole.

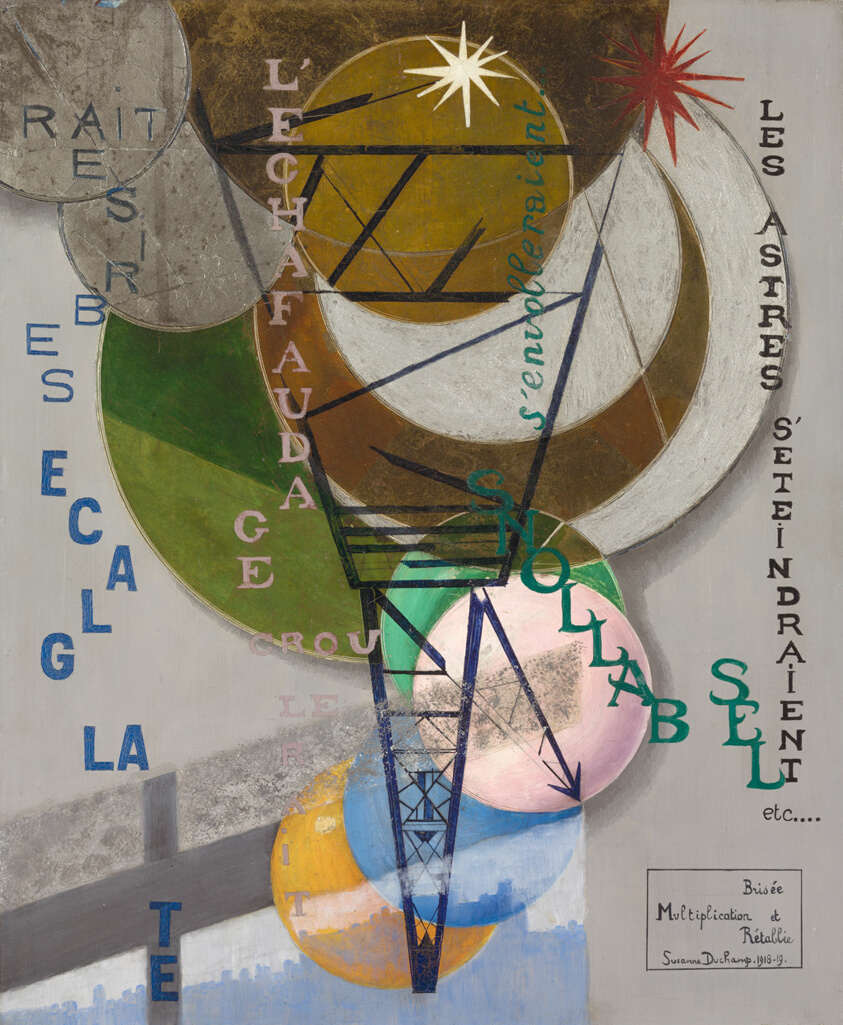

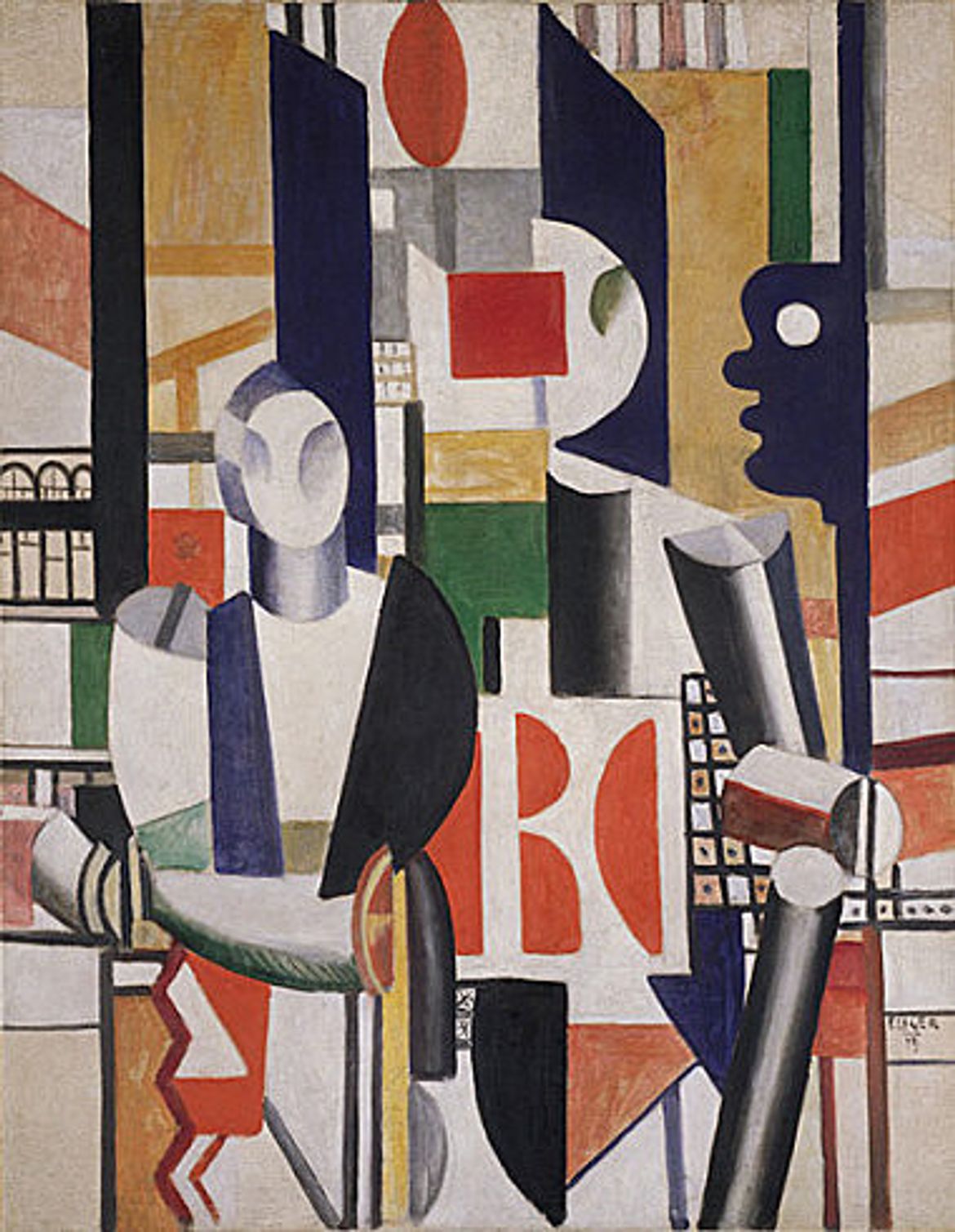

From the Philadelphia Museum of Art website:

Fernand Léger served in the French army throughout the four years of World War I, and came away convinced that modern conflict had imposed a new mentality—unsentimental, dynamic, ever shifting. Modern painting, he believed, should reflect this new turn of mind. He would come to rank this enormous painting, the grand culmination of a sequence of works on the same subject painted after the war’s end, as a major career accomplishment. Stenciled letters stand for advertising billboards, a balcony railing signifies the facade of a building, and bits of metal girder denote construction machinery, scaffolding, or electrical pylons. These glimpses of a cityscape are set within a taut framework of vivid hues and clashing shapes, producing visual intensity to rival the modern urban environment. The composition is mural-like in its sweep, flatness, and scale, enveloping the viewer like a theater backdrop or a movie screen.

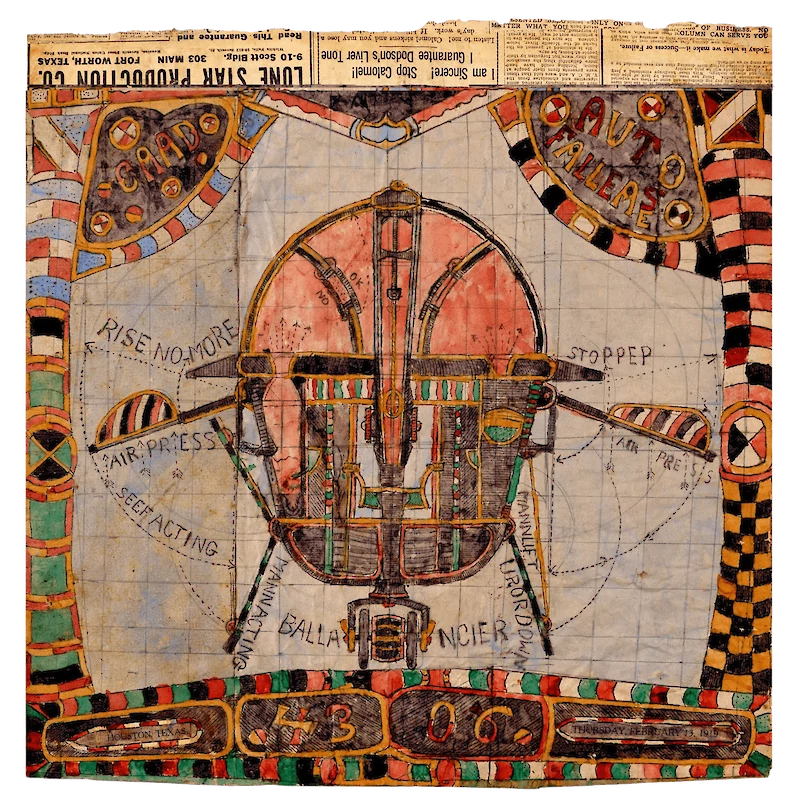

Dellschau’s earliest known work is a diary dated 1899, and the last is an 80-page book dated 1921-1922, giving his career as an artist a 21-year span. His work was in large part a record of the activities of the “Sonora Aero Club,” of which he was a purported member. Dellschau’s writings describe the club as a secret group of flight enthusiasts who met in Sonora, California in the mid-19th century. According to Dellschau, one of the club members discovered a formula for an anti-gravity fuel called “NB Gas.” The club mission was to design and build the first navigable aircraft using the NB Gas for lift and propulsion. Dellschau called these flying machines Aeros. His collages incorporate newspaper clippings of then-current news articles about aeronautical advances and disasters.

NOTES ON PROUN

Proun is an acronym of the Russian words “PROyect Utverzhdenia Novogo” (Project for the Affirmation of the New).

From the Guggenheim website: “These nonobjective compositions broadened Malevich’s Suprematist credo of pure painting as spiritually transcendent into an interdisciplinary system of two-dimensional, architectonic forms rendered in painted collages, drawings, and prints, with both utopian and utilitarian aspirations. Blurring the distinctions between real and abstract space — a zone that Lissitzky called the “interchange station between painting and architecture” — the Prouns dwell upon the formal examination of transparency, opacity, color, shape, line, and materiality, which Lissitzky ultimately extended into three-dimensional installations that transformed our experience of conventional, gravity-based space. Occasionally endowed with cryptic titles reflecting an interest in science and mathematics, these works seem engineered rather than drawn by hand — further evidence of the artist’s growing conviction that art was above all rational rather than intuitive or emotional.”

MORE RADIUM AGE SCI FI ON HILOBROW: RADIUM AGE SERIES from THE MIT PRESS: In-depth info on each book in the series; a sneak peek at what’s coming in the months ahead; the secret identity of the series’ advisory panel; and more. | RADIUM AGE: TIMELINE: Notes on proto-sf publications and related events from 1900–1935. | RADIUM AGE POETRY: Proto-sf and science-related poetry from 1900–1935. | RADIUM AGE 100: A list (now somewhat outdated) of Josh’s 100 favorite proto-sf novels from the genre’s emergent Radium Age | SISTERS OF THE RADIUM AGE: A resource compiled by Lisa Yaszek.