VURT YOUR ENTHUSIASM (INTRO)

By:

July 1, 2024

One in a series of 25 enthusiastic posts, contributed by 25 HILOBROW friends and regulars, on the topic of science fiction novels and comics from the Eighties (1984–1993, in our periodization schema). Series edited by Josh Glenn.

This summer, I’ve invited 25 HILOBROW friends and regular contributors to contribute to a series on the topic of favorite science-fiction novels or comics published in the Eighties (1984–1993, in our periodization scheme). This is sequel of sorts to sff-oriented series such as CROM YOUR ENTHUSIASM (Fantasy novels, 1934–1943), KLAATU YOU (favorite pre-Star Wars sci-fi movies), and KIRK YOUR ENTHUSIASM, one of our first-ever enthusiasm series.

Here’s the VURT YOUR ENTHUSIASM lineup:

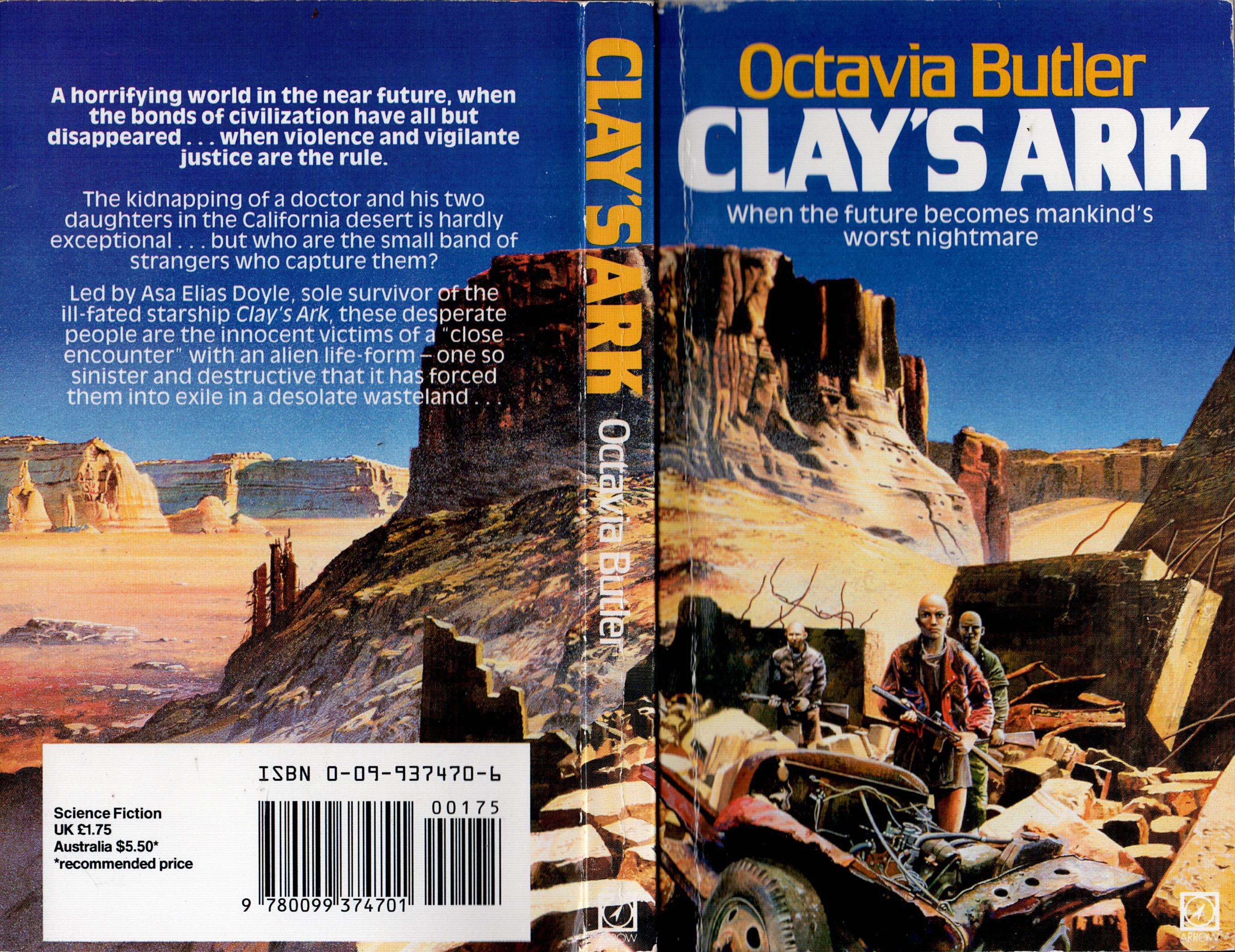

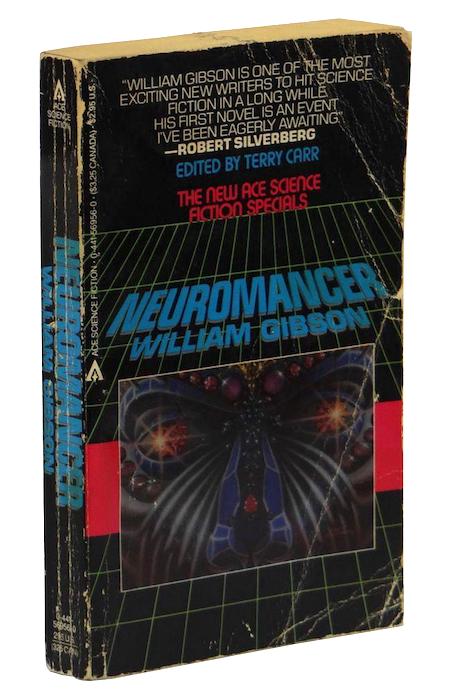

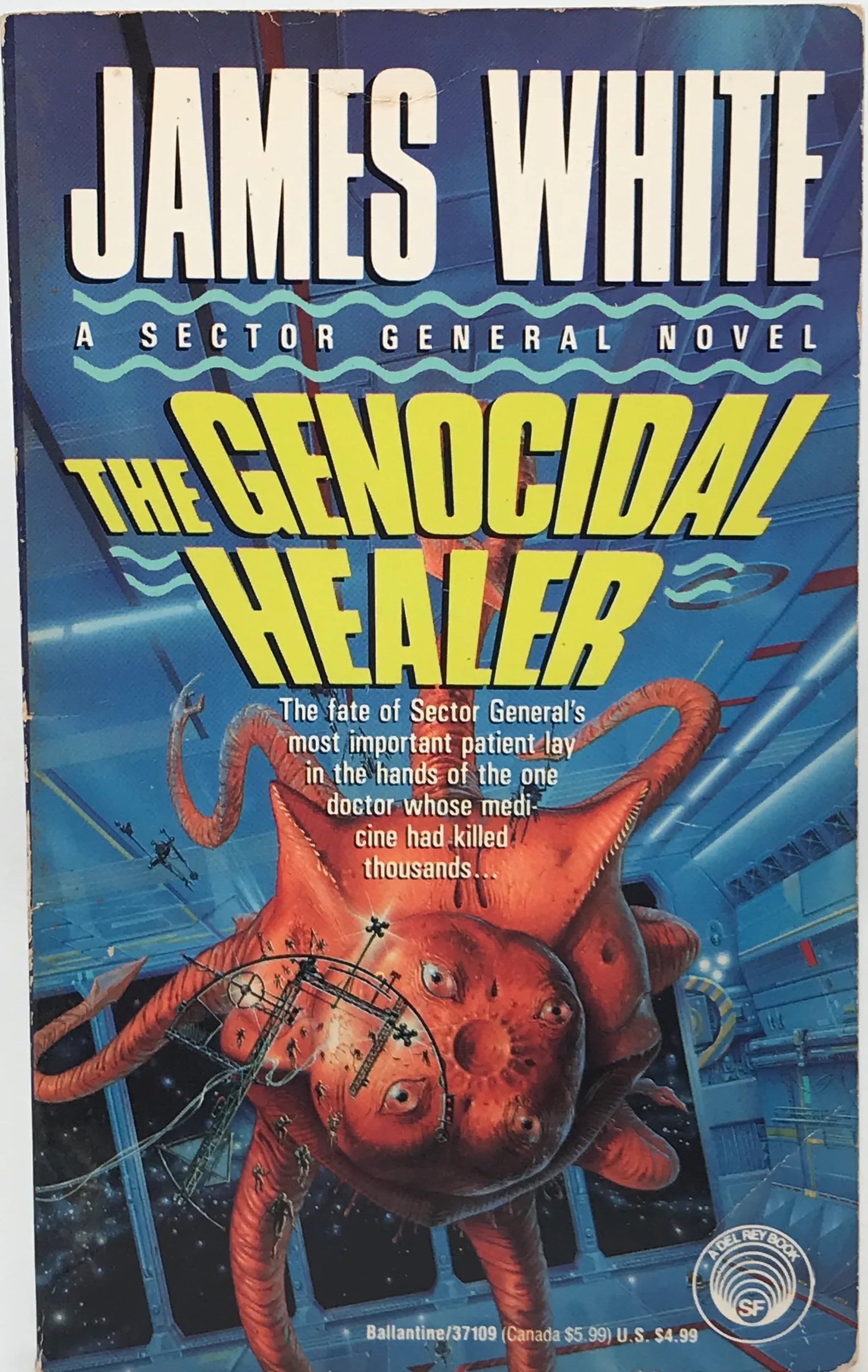

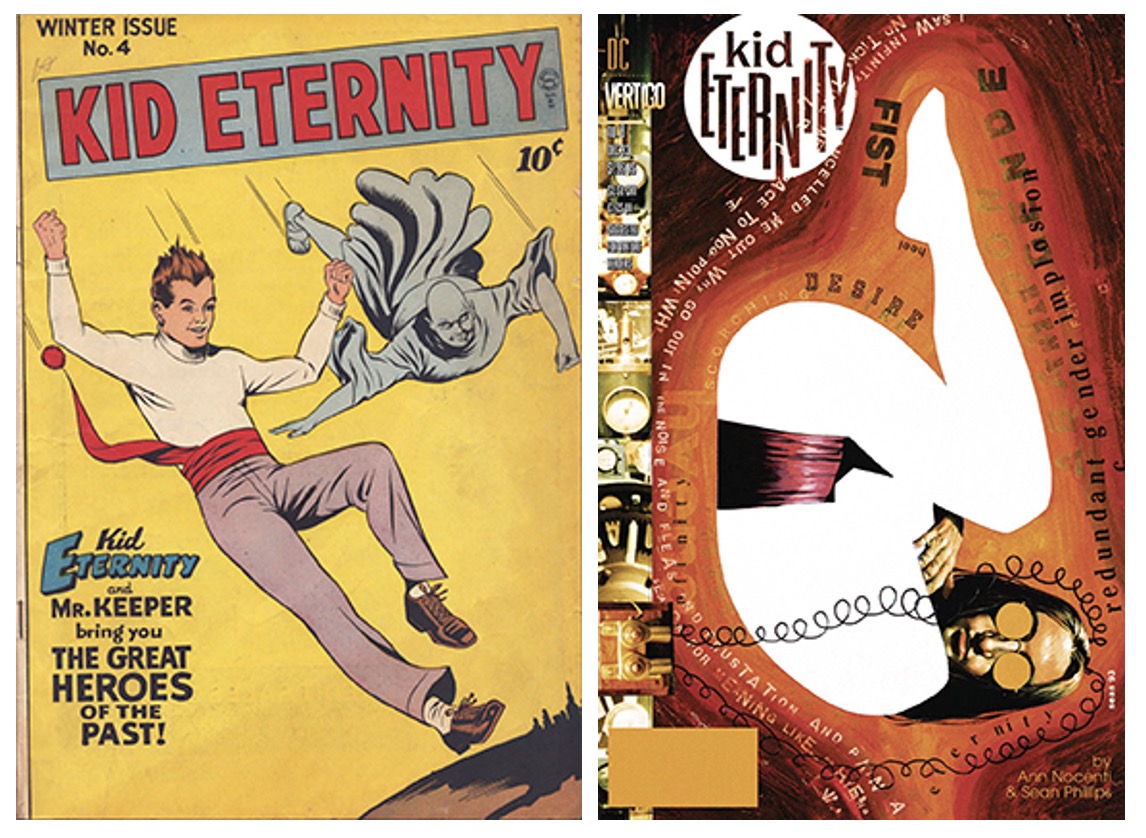

Mark Kingwell on SNOW CRASH | Mandy Keifetz on THE GENOCIDAL HEALER | Matthew De Abaitua on SWAMP THING | Carlo Rotella on THE PLAYER OF GAMES | Lynn Peril on GEEK LOVE | Stephanie Burt on THE CARPATHIANS | Josh Glenn on DAL TOKYO | Deb Chachra on THE HYPERION CANTOS | Adam McGovern on KID ETERNITY | Nikhil Singh on THE RIDDLING REAVER | Judith Zissman on RANDOM ACTS OF SENSELESS VIOLENCE | Ramona Lyons on PARABLE OF THE SOWER | Jessamyn West on the MARS TRILOGY | Flourish Klink on THE DOMESDAY BOOK | Matthew Battles on THE INTEGRAL TREES | Tom Nealon on CLAY’S ARK | Sara Ryan on SARAH CANARY | Gordon Dahlquist on CONSIDER PHLEBAS | Alex Brook Lynn on VURT | Miranda Mellis on STARS IN MY POCKET LIKE GRAINS OF SAND | Nicholas Rombes on RADIO FREE ALBEMUTH | Adelina Vaca on NEUROMANCER | Marc Weidenbaum on AMERICAN FLAGG! | Peggy Nelson on VIRTUAL LIGHT | Michael Grasso on WILD PALMS.

I’m very grateful to the series’ talented, generous contributors, many of whom have donated their honoraria to COVENANT HOUSE — which provides housing and support services to youth facing homelessness.

VURT YOUR ENTHUSIASM kicks off tomorrow. Enjoy!

Below are a couple of notes on thematic threads I’ve noticed running through the series…

First of all, 1984–1993 is science fiction’s cyberpunk era — from Neuromancer (1984) to, let’s say, Snow Crash (1992). Stephenson’s novel, which pushes Gibson’s motifs (AI and cyberware mediating between us and reality in ways that are liberating, yet uncanny and ominous; alienated hackers surfing the datasphere for profit and kicks; the world’s governments supplanted by megacorporations and their mercenaries; major cities all resembling Ridley Scott’s future Los Angeles) to satirical extremes, suggests a kind of last hurrah for cyberpunk — though of course aspects of cyberpunk are still very influential.

Adelina Vaca finds Neuromancer prescient, depicting as it does a next-generation AI that “doesn’t deal with binary data, but instead with dreams and personality.” (From this sort of matrix, she points out, there is no escape… and in fact, we might not even want to escape it.) Writing about Snow Crash, Mark Kingwell notes that the author’s insights about “democracy’s spectacular decline into spectral politics of identity, the dissolution of citizenship in a flurry of tech, power, and tribal enthusiasm” have also proven prescient.

Other cyberpunk re-readers found themselves transported not into the future, but back to their own past. “I was just a kid when I read it but it shaped the way I saw things,” writes Alex Brook Lynn of Vurt, a sort-of-cyberpunk, druggy dystopia. “People are horrible, but you can love your abuser; acid can make you a hero; there might be a fun-filled multi-colored brick road to redemption.” Peggy Nelson, after revisiting another Gibson novel from this era, concludes: “To reread Virtual Light from the vantage point of now was not to vicariously inhabit the Bridge, as I had expected, but to see the glowing outlines of a future that did not happen, superimposed over the sadder, more prosaic one that did.”

Considering Genocidal Healer, which is set in a multispecies hospital on the galactic rim, Mandy Keifetz identifies xenophobia (and anti-xenophobia) as a key theme of Eighties science fiction. Optimistically, she points out: “At Sector General xenophobia always loses, and peace always wins.” Miranda Mellis draws our attention to Samuel R. Delany’s effort, in Stars in My Pocket Like Grains of Sand, to prompt readers to recognize ourselves as alien: “Here pronouns indicate contingent becoming, rather than categorized beings. In the same way one says, ‘I’m boiling’ to describe oneself on a hot day, gender is, among other things, a way to describe transient states, for example of excitation and desire.”

Other readers also noticed a tendency of some of our favorite sf novels from the Eighties to privilege heterogeneity over homogeneity. The Hyperion Cantos duology is a parable, suggests Deb Chachra, about humankind’s tendency to “colonize new worlds and eradicate any indigenous lifeforms.” (The author of 2023’s How Infrastructure Works: Inside the Systems That Shape Our World, Chachra notes that it’s infrastructure, in the Hyperion Cantos, that makes homogeneity possible.) Speaking of indigenous lifeforms, Matthew Battles (editor of Arnoldia: the Nature of Trees, a magazine exploring “the urgency of tree-entangled science, history and storytelling for our time”) is fascinated by Larry Niven’s titular “integral trees”: “Each integral tree is a world, a landscape, with springs coursing through rifts in bark, and a variously three-eyed, tentacled menagerie erupting from holes or falling everywhere from out of the clouds.”

The opposite of xenophobia is, perhaps, familial togetherness, a state of being that science fiction from this era treats as a Le Guinian ambiguous utopia. “Strip away the book’s Grand Guignol effects,” Lynn Peril writes of Geek Love, “and you’ll find a story of family jealousies and sorrow.” Even more extreme, Tom Nealon notes in his essay on Clay’s Ark, is a scenario in which the characters who are infected by a mutating virus become “transitional organisms — no longer really human, but not the perfected creature that their offspring will be either. As a result, the main characters can’t really relate to one another any more…”

The Eighties saw a flourishing of postmodernism and pop surrealism in science fiction; story telling itself was colonized and mutated from within. For example, in Alan Moore’s run on DC’s Swamp Thing comic, in Matthew De Abaitua’s analysis, we find a “yearning to make the border of world and text permeable so that there can be free, magical traffic between them.” In Annie Nocenti and Sean Phillips’ run on DC’s Kid Eternity comic, enthuses Adam McGovern, “ancient pantheons, psychic archetypes, creatures of literary fantasy and figures of unreliable history circle and collide.” Reminiscing fondly about an installment in Great Britain’s Fighting Fantasy series of single-player RPG books, Nikhil Singh recalls the following phantasmagoria: “Invisible bridges. Upside-down waterfalls. Leprechauns surrounded by gigantic butterflies, feasting on scuttling, miniature dinosaurs. Powdered creatures (just add water.) Etcetera.”

Karen Joy Fowler’s Sarah Canary , meanwhile, may or may not be science fiction at all: “We can’t properly perceive her,” Sara Ryan notes of the titular character. “Although each character’s interactions with Sarah Canary can be read as a version of first contact, we’re never told whether or not she’s an alien.” And then there’s Bruce Wagner and Julian Allen’s comic Wild Palms, which depicts Los Angeles as “a shattered mirror populated by vacant ghosts, where no one is innocent, no one is guilty,” as Michael Grasso puts it, “but everyone is wearing fantastic vintage eyeglasses.” Is this sci-fi, Grasso wonders — or just LA?

Philip K. Dick, a key precursor to cyberpunk, died just before the beginning of this era for sf… but his Radio Free Albemuth appeared in 1985. “Rather than being too paranoid for its own good — as many reviews of this posthumous novel have suggested — Radio Free Albemuth, it turns out, might not have been paranoid enough,” laments Nicholas Rombes — who points to the novel’s President Ferris Fremont and the New American Way. Octavia E. Butler’s Parable of the Sower, too, predicts our present moment, as Ramona Lyons points out: “Butler has an authoritarian politician raise the words with which we’ve become so familiar in these times: ‘Make America great again.'” Brr.

An apocalyptic-yet-hopeful vibe infuses many of our favorite Eighties sf stories. Doomsday Book, writes Flourish Klink, “carefully and precisely depicts the ways that humans care for each other, even in the greatest extremity of disaster.” Judith Zissman revisits Random Acts of Senseless Violence, which gives us, she enthuses, “the sudden raw feelings of early adolescence, newfound queer joy amidst the rubble of abandoned buildings, and the terror of taking up the necessary violence of petty thievery and self-defense.” And the protagonist of The Carpathians, another sf novel that may or may not be sf, is “in search of… something else,” notes Stephanie Burt, “something that comes at the end of the world, in ‘the brief time that may be left for all the old written and spoken languages.'”

In Eighties science fiction, dystopia and utopia are mutually imbricated, and there’s no simple solution to humankind’s problems. “The plot is a complex tale of bending the environment towards human habitation, with a lot of push/pull of various philosophies debating how to do that process in the best way, writes Jessamyn West of the Mars trilogy. “It’s hard to settle on what ‘best’ means.” Revisiting the inaugural Culture novel, Consider Phlebas, Gordon Dahlquist approves of Iain M. Banks’ double consciousness: “His narration walks a tightrope between full engagement with his characters and their circumstances and just a touch of stepped-back, ironic distance that allows us to preserve a critical eye” — i.e., a critical eye on whether or not the Culture is utopian.

Hope and a realistic view of what’s possible can and does coexist in these novels. In Parable of the Sower, the protagonist packs more than survival supplies in her bug-out bag, notes Ramona Lyons: She also develops a philosophy “that the only constant in life and the world is change, and that we can and should prepare for change as much as we can.” And Carlo Rotella, who writes so well, in his own books, about how people get good at things, approvingly notes that The Player of Games is ultimately not about winning or losing games but rather the experience of “moving and thinking in the game world” — which, when done well, is its own reward.

JACK KIRBY PANELS | CAPTAIN KIRK SCENES | OLD-SCHOOL HIP HOP | TYPEFACES | NEW WAVE | SQUADS | PUNK | NEO-NOIR MOVIES | COMICS | SCI-FI MOVIES | SIDEKICKS | CARTOONS | TV DEATHS | COUNTRY | PROTO-PUNK | METAL | & more enthusiasms!