RADIUM AGE ART (1917)

By:

June 25, 2024

A series of notes regarding proto sf-adjacent artwork created during the sf genre’s emergent Radium Age (1900–x1935). Very much a work-in-progress. Curation and categorization by Josh Glenn, whose notes are rough-and-ready — and in some cases, no doubt, improperly attributed. Also see these series: RADIUM AGE TIMELINE and RADIUM AGE POETRY.

RADIUM AGE ART: 1900 | 1901 | 1902 | 1903 | 1904 | 1905 | 1906 | 1907 | 1908 | 1909 | 1910 | 1911 | 1912 | 1913 | 1914 | 1915 | 1916 | 1917 | 1918 | 1919 | 1920 | 1921 | 1922 | 1923 | 1924 | 1925 | 1926 | 1927 | 1928 | 1929 | 1930 | 1931 | 1932 | 1933 | 1934 | 1935 | THEMATIC INDEX.

Zürich Dada, with Tzara at the helm, published the art and literature review Dada beginning in July 1917, with five editions from Zürich and the final two from Paris.

Proletkult — an experimental Soviet artistic institution that arose in conjunction with the Russian Revolution of 1917 — begins now. Proletkult aspired to radically modify existing artistic forms by creating a new, revolutionary working-class aesthetic, which drew its inspiration from the construction of modern industrial society in backward, agrarian Russia.

Productivism — characterized by its spare geometry, limited color palette, and Cubist and Futurist influences — also begins around now. “We declare uncompromising war on art!” Aleksei Gan wrote in a 1922 manifesto.Alexander Rodchenko, Varvara Stepanova, Kazimir Malevich, El Lissitzky, Liubov Popova, and others similarly renounced pure art in favor of serving society. See Rodchenko’s famous Lilya Brik poster (1924), calling for Russian books in all branches of knowledge.

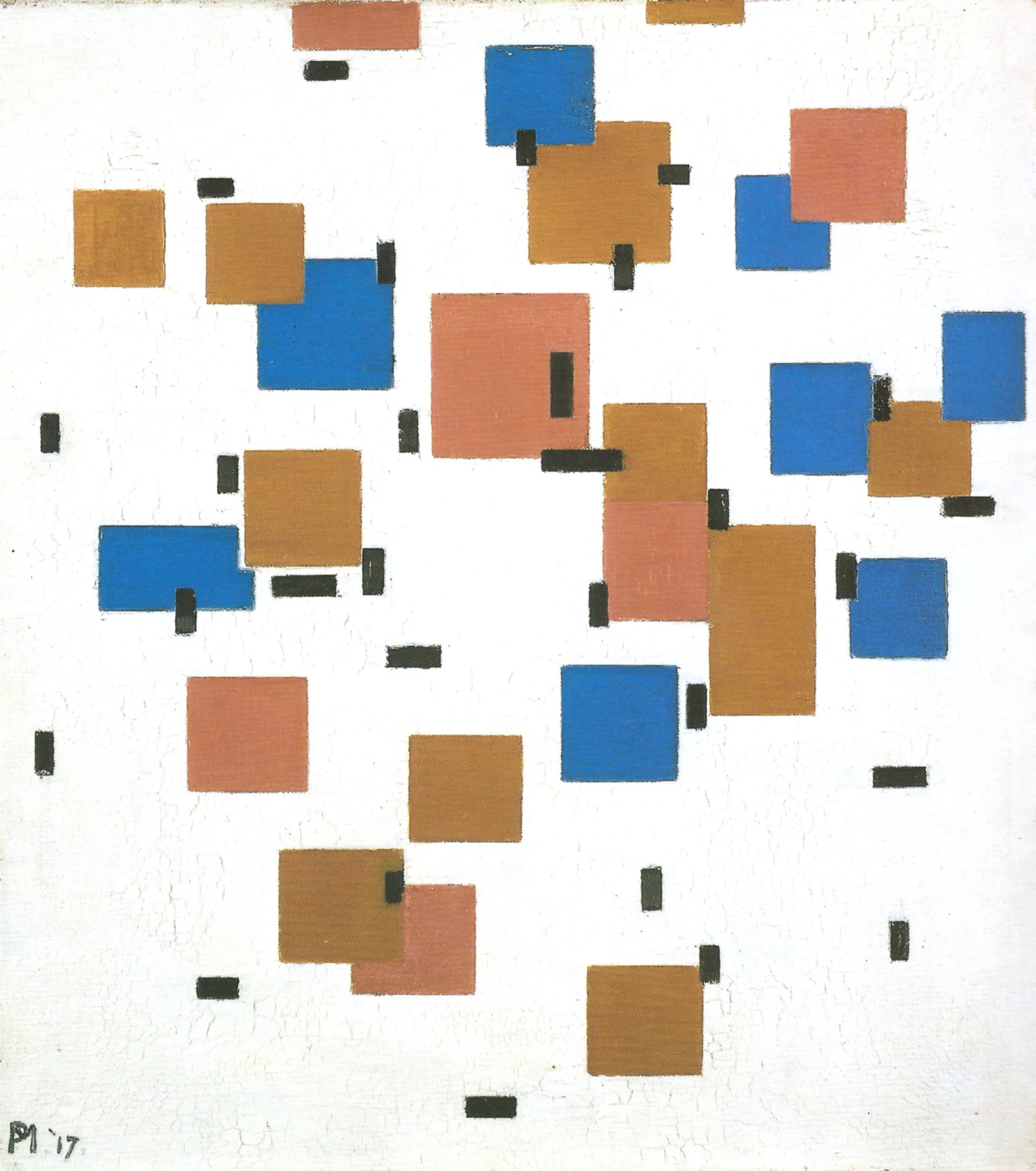

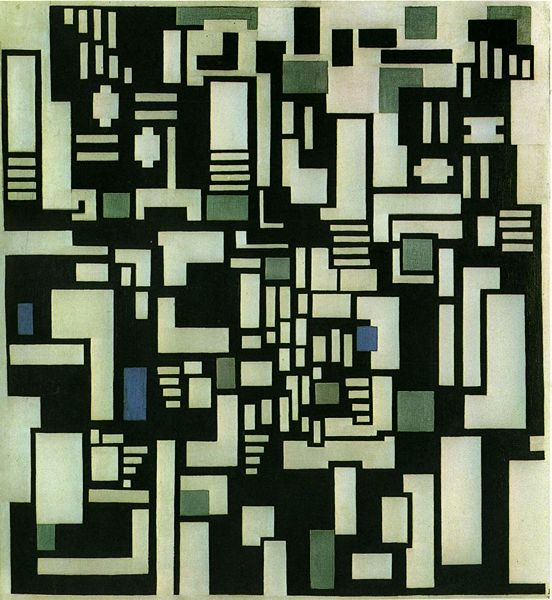

De Stijl (“The Style”) gets its start c. 1917. Founded in Amsterdam by Theo van Doesburg, Piet Mondrian, and Jacobus Johannes Pieter Oud, De Stijl is infused with a great deal of mysticism — primarily from Mondrian’s devotion to Theosophy. The movement is also influenced by Cubism, though members of De Stijl feel that Picasso and Braque have failed to go far enough into the realm of pure abstraction. Working mainly in an abstract style and with unadorned shapes — such as straight lines, intersecting plane surfaces, and basic geometrical figures — and the primary colors and neutrals, they seek to investigate the laws of equilibrium apparent in both life and art.

Mondrian, in 1917’s “The New Plastic in Painting”: “the machine displaces natural power” in modern society, with the result that “life grows increasingly abstract.” The trend to “abstract plastic expression” in painting, he adds, results from “the evolution of the consciousness of our time towards the abstract.”

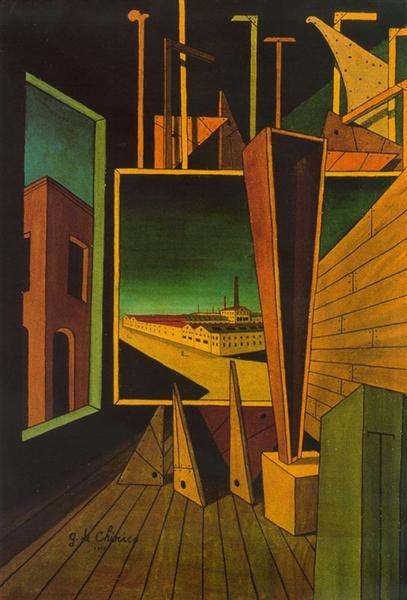

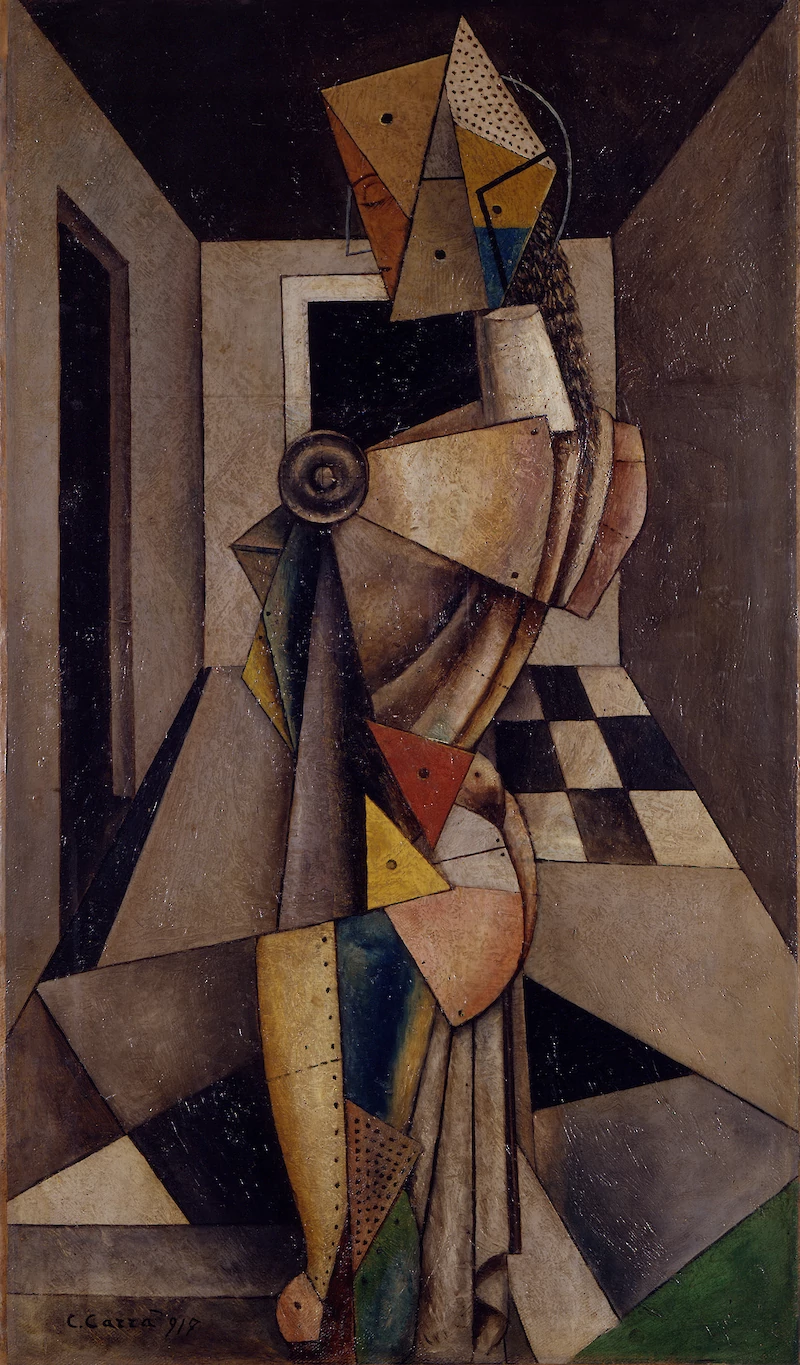

Metaphysical painting officially gets its start as a meovement this year. Developed by the Italian artists Giorgio de Chirico and Carlo Carrà. The movement began in 1910 with de Chirico, whose dreamlike works with sharp contrasts of light and shadow often had a vaguely threatening, mysterious quality, “painting that which cannot be seen.” De Chirico, his younger brother Alberto Savinio, and Carrà formally established the school and its principles in 1917.

The United States declares war on Germany.

The February Revolution begins in Russia. Emperor Nicholas II of Russia abdicates his throne and his son’s claims. Vladimir Lenin arrives at the Finland Station in Petrograd. Leon Trotsky is elected Chairman of the Petrograd Soviet. October Revolution in Russia.

The British Foreign Secretary Arthur Balfour makes the Balfour Declaration, proclaiming British support for the “establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people.”

William Butler Yeats’s wife begins to produce automatic writing in 1917; in 1919, she will begin to communicate with the spirits via sleep-talking. Her revelations will serve as the basis of Yeats’s A Vision (1925), the summa of his metaphysical thinking, which sets forth what he’d call his “public philosophy.”

Ernest Rutherford achieves nuclear transmutation of nitrogen into oxygen, in 1917; this is the first observation of a nuclear reaction, via which he also discovers and names the proton.

Also see: RADIUM AGE: 1917.

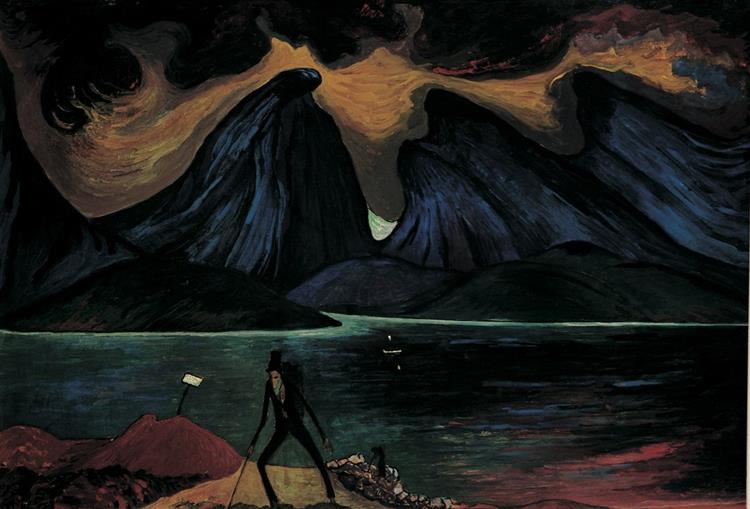

From MoMA’s website:

George Grosz’s Explosion transports the horrors of World War I home, to Berlin. With a fiery glow in the background, collapsing high-rise buildings pinwheel around a black vortex. Windows shatter and smoke pours into the nighttime sky. Slices of half-naked body parts, embracing couples, and shadowy faces appear amid the chaos brought about by man-made, not natural, disaster. Grosz welcomed the purge of old society in this and other paintings showing cities in the throes of destruction that he made after he was discharged from the German army, in spring 1917, as “permanently unfit.”

Multiple, shifting perspectives and intense color heighten the feelings of instability and danger, and demonstrate his reworking of the stylistic approaches of the Expressionists and Italian Futurists. In style and theme, Explosion also recalls the apocalyptic paintings of Ludwig Meidner, whose studio and weekly gatherings Grosz frequented while in Berlin, and the brilliantly colored urban landscapes of French painter Robert Delaunay.

Painted after his nervous breakdown and release from the German army, Grosz’s Großstadt (Metropolis) presents the city as a place that is as hellish as the battlefield. Bathed in shades of fiery red, flame blue, and rich purple, buildings topple and streets buckle. Tilted on a diagonal, the composition conveys the social upheavals of wartime. Multiple perspectives merge to create a disorienting space and collapse distinctions between inside and outside. Moral order has broken down as well. Grosz’s zig-zag composition plots a tour through the city’s debauchery. — excerpt from Heather Hess’s German Expressionist Digital Archive Project, German Expressionism: Works from the Collection.

In September 1916, Léger almost died during a mustard gas attack by the German troops at Verdun. During a period of convalescence in Villepinte he painted The Card Players (1917), the robot-like, monstrous figures of which reflect his experience of the war. As he explained:

…I was stunned by the sight of the breech of a 75 millimeter in the sunlight. It was the magic of light on the white metal. That’s all it took for me to forget the abstract art of 1912–1913. The crudeness, variety, humor, and downright perfection of certain men around me, their precise sense of utilitarian reality and its application in the midst of the life-and-death drama we were in … made me want to paint in slang with all its color and mobility.

This work marked the beginning of Léger’s “mechanical period,” during which the figures and objects he painted were characterized by sleekly rendered tubular and machine-like forms.

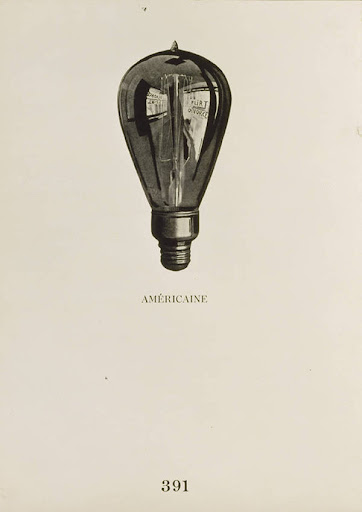

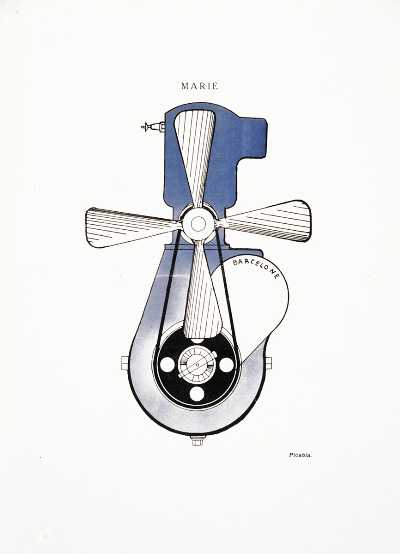

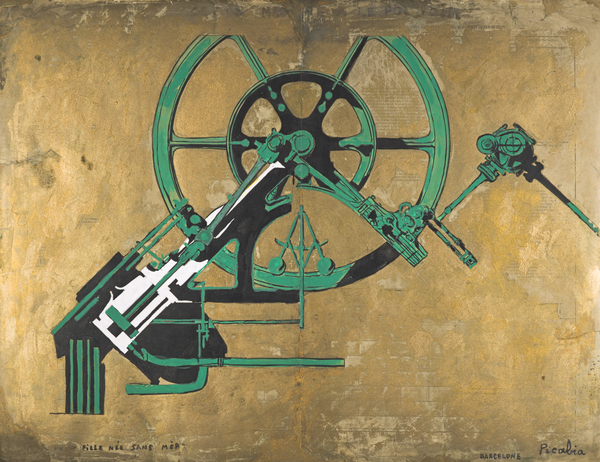

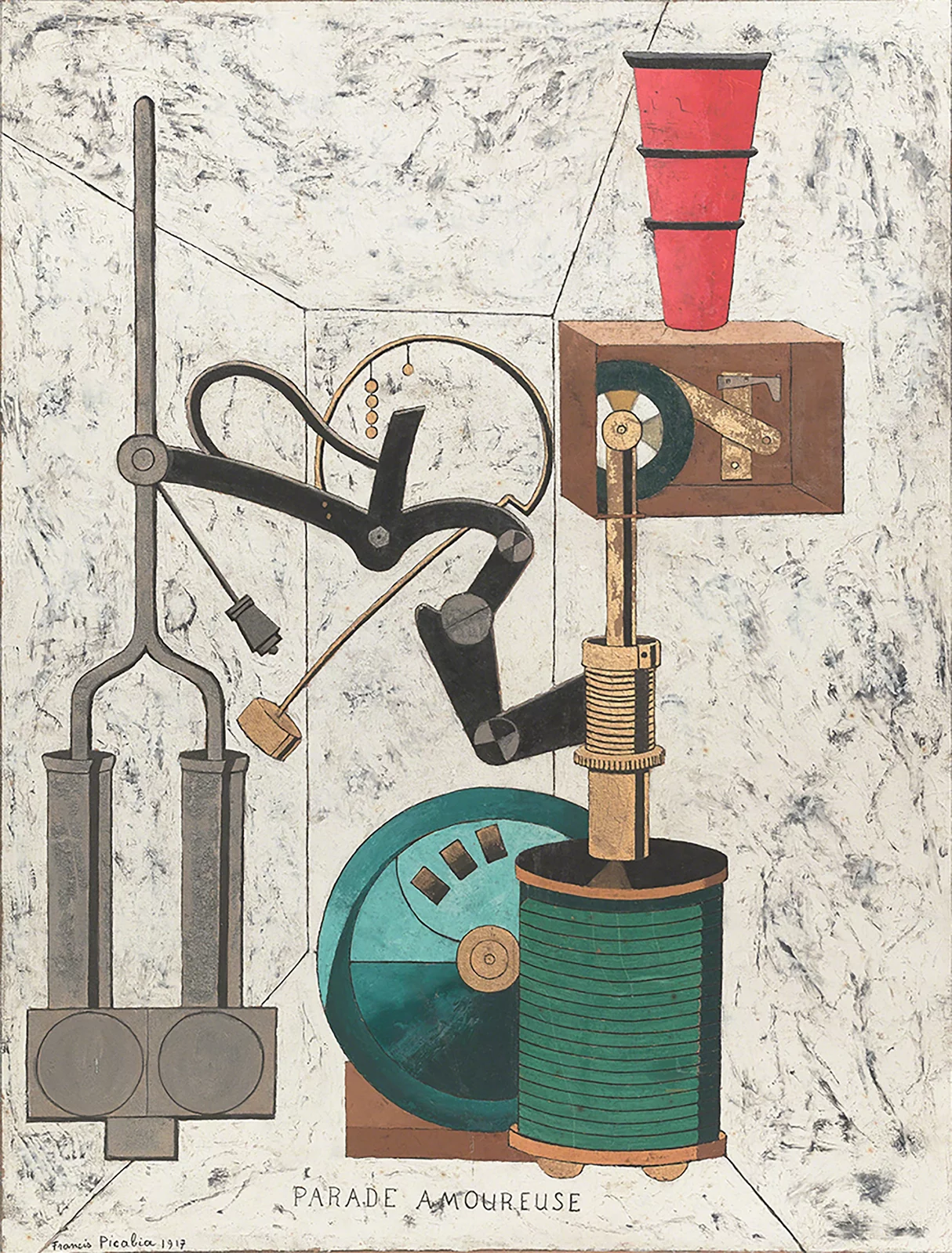

Published 1917-1924 in Barcelona, New York, Zürich, and Paris in nineteen issues, Picabia modeled 391 after Alfred Stieglitz’s 291, a review to promote the photographer’s 291 Gallery and his artistic circle.

Picabia’s paintings and drawings reproduced in the first numbers of 391 are still very close to his New York work of 1915, although the titles reflect his Spanish surroundings: Novia and Flamenca. They vary, broadly, from composite fantasy machines with sexual analogies, to dry copies of machines or machine parts presented as portraits.

In 391 no. 3, Marie (presumably Laurencin) is symbolised by the fan belt of a car, an object that Picabia particularly liked. Also in no. 3 Apollinaire (deliberately juxtaposed with his former mistress) is a motor-pump, with the inscription “he who does not praise time past.”

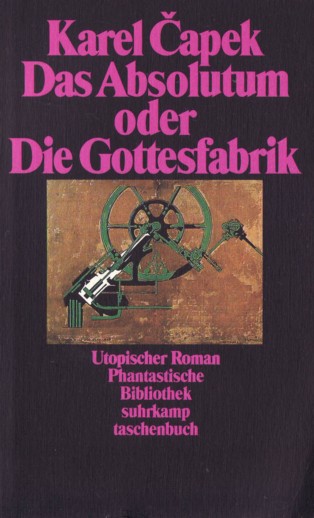

See below for an example of this artwork used for an sf book cover illustration.

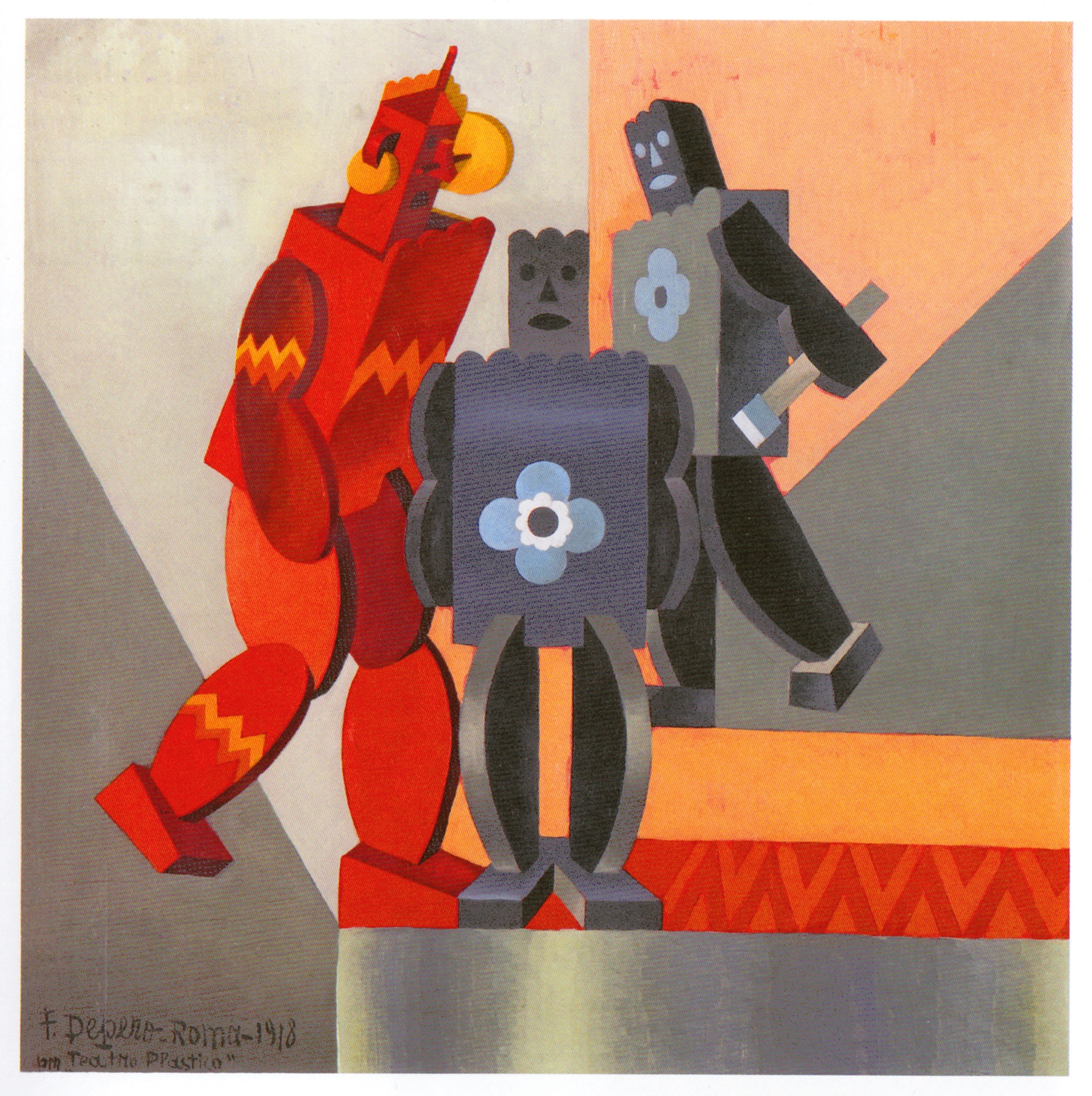

Here the artist anticipates in the theater a transformed environment for all cultures and races, including humans, animals and artificial beings.

Machine aesthetics were a popular field of theatrical exploration in many countries, ranging from capitalist America (via Fascist Italy) to Bolshevik Russia. Well-known examples were the commercial girl revues, the experiments at the Bauhaus stage workshop, Vsevolod Meyerhold’s biomechanics, and Nikolai Foregger’s machine dances.

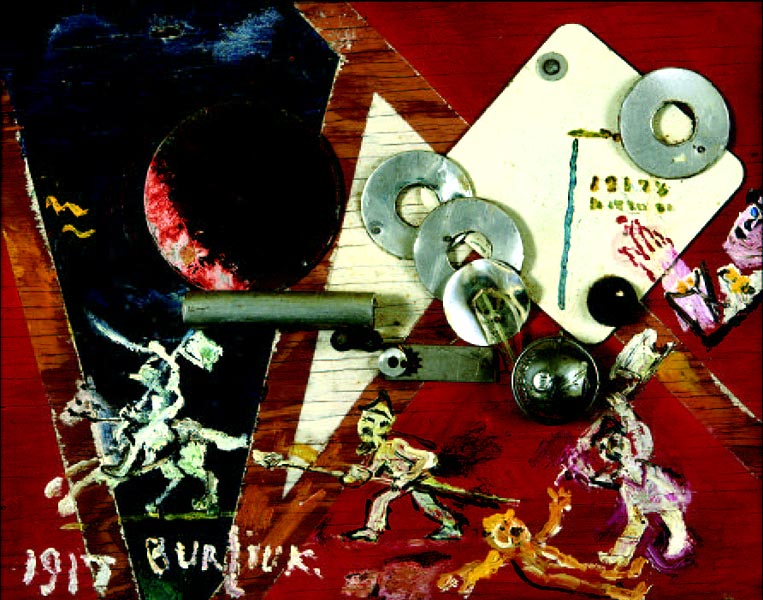

Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven, 1917

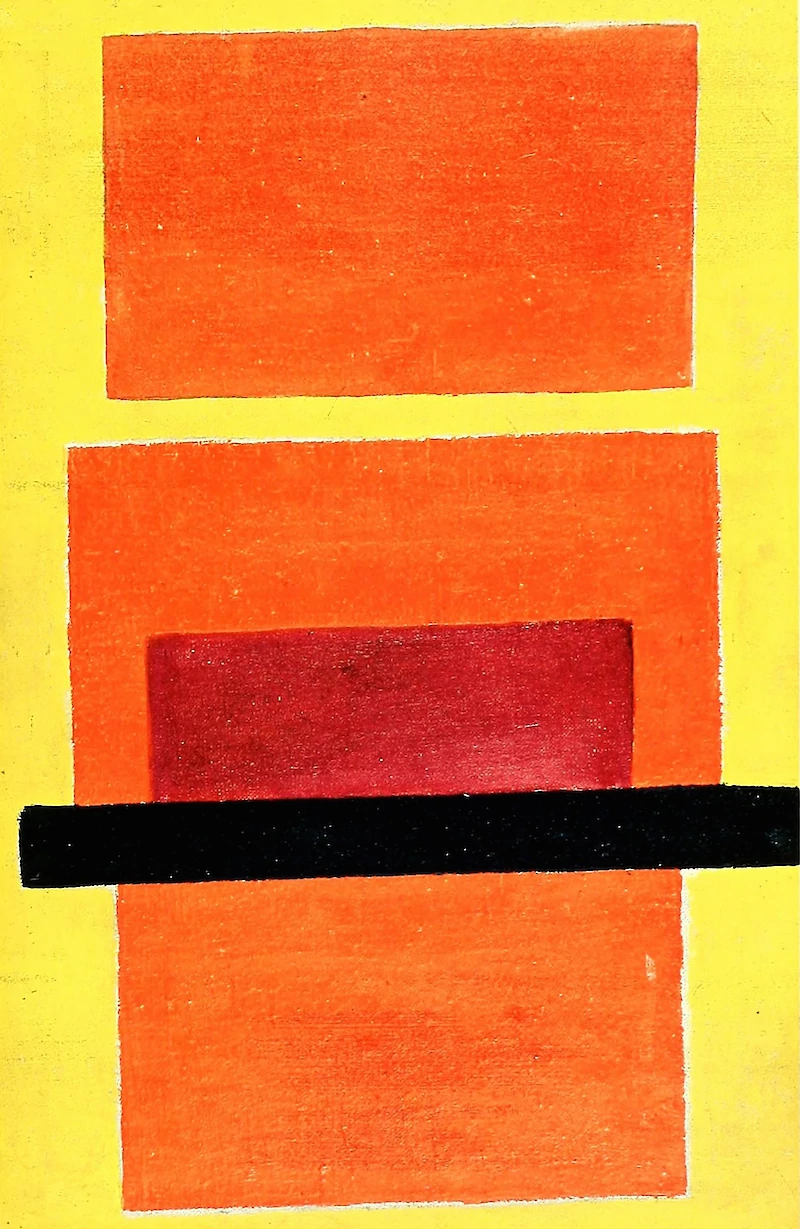

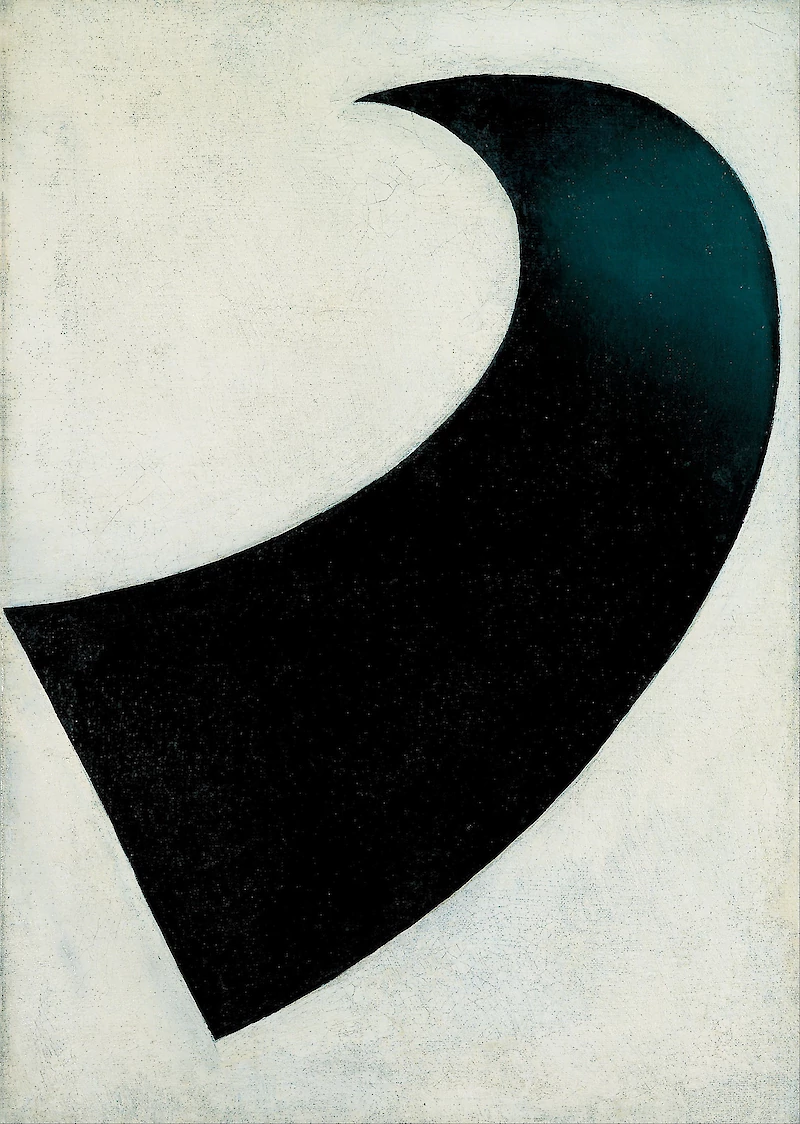

One of a series of works by this title. Influenced by her long visits to Europe before WWI, Popova helped to introduce the Cubist and Futurist ideas of France and Italy into Russian art. From the book MoMA Highlights: 350 Works from the Museum of Modern Art New York (second edition, 2004):

No matter how abstract European Cubism and Futurism became, they never completely abandined recognizable imagery, whereas Popova developed an entirely nonrepresentational idiom based on layered planes of color. The catalyst in this transition was Kazimir Malevich’s Suprematism, an art of austere geometric shapes. But where Suprematism was infused with the desire for a spiritual or cosmic space, Popova’s concerns were purely pictorial.

From MOMA’s “Inventing Abstraction” series:

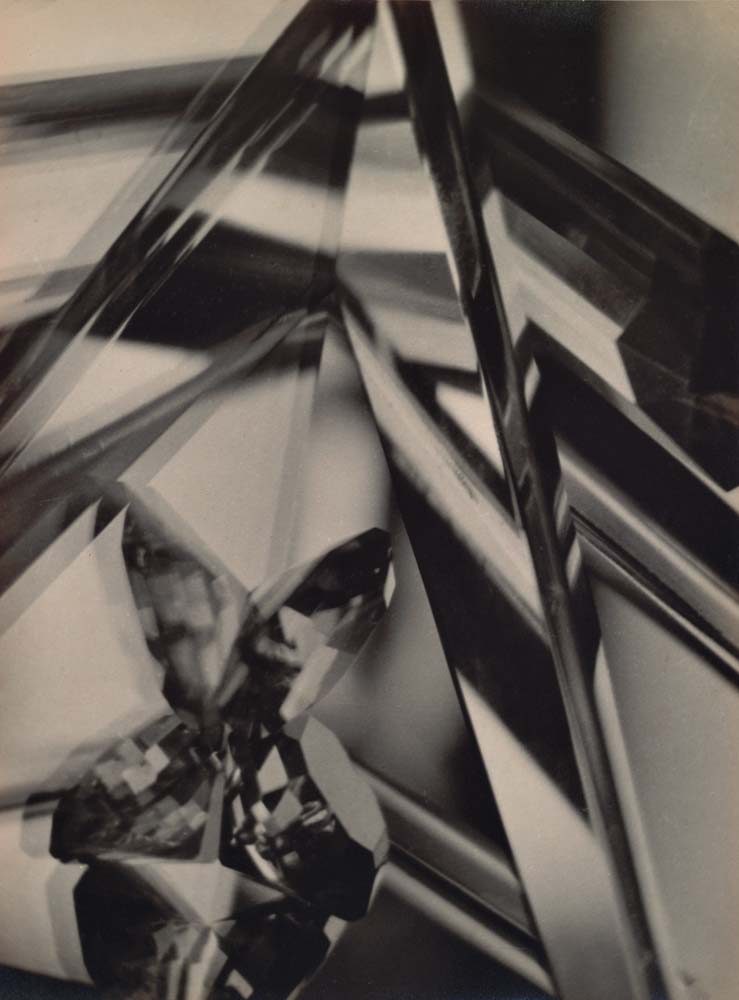

The intricate patterns of light and line in this photograph, and the cascading tiers of crystalline shapes, were generated through the use of a kaleidoscopic contraption invented by the American/British photographer Alvin Langdon Coburn, a member of London’s Vorticist group. To refute the idea that photography, in its helplessly accurate capture of scenes in the real world, was antithetical to abstraction, Coburn devised for his camera lens an attachment made up of three mirrors, clamped together in a triangle, through which he photographed a variety of surfaces. The poet and Vorticist Ezra Pound coined the term “vortographs” to describe Coburn’s experiments. Although Pound went on to criticize images like this one as lesser expressions than Vorticist paintings, Coburn’s work would remain influential.

Seiji Togo’s “Kanojo no subete” (1917).

A Futurist-style abstraction of a female form. The artist met Filippo Marinetti in 1916 while studying in France. I’ve read about this artwork here; I haven’t seen it.

From the Brooklyn Museum’s website:

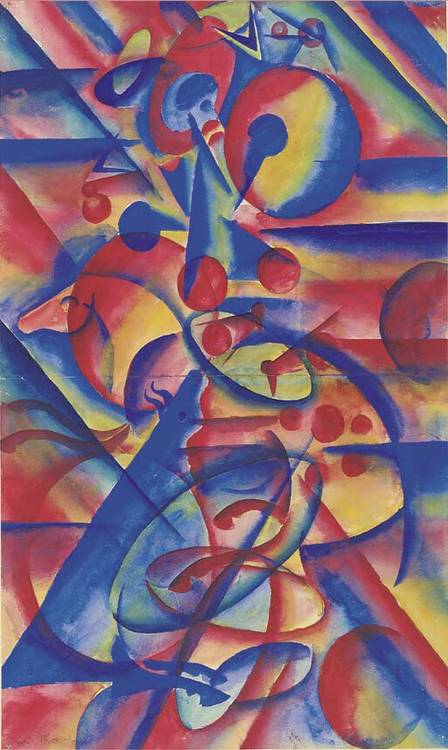

Although this abstract composition bears many traces of European Cubism—angular shapes, fragmented forms, and multiple perspectives—it asserts the primacy of color as a key component of space and form. In 1912 Stanton Macdonald-Wright, together with the painter Morgan Russell, coined the term Synchromism to describe abstract compositions primarily concerned with the rhythmic use of color—a phenomenon they likened to a symphony’s use of sound. Synchromism was one of many diverse approaches to abstraction that flourished in the Americas and Europe in the 1910s, radically departing from traditional vocabularies of painting and sculpture.

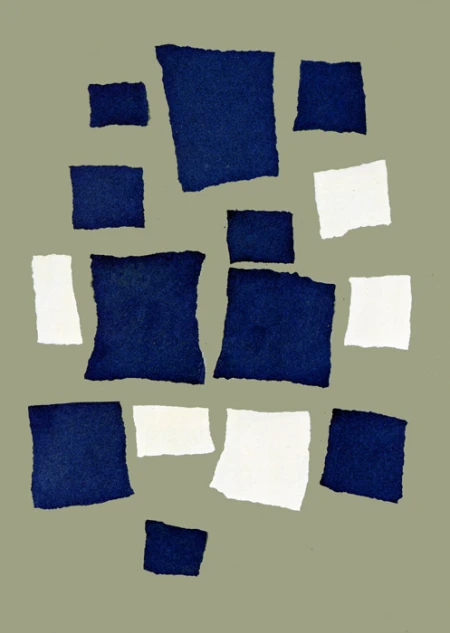

Arp’s “Collage Arranged According to the Laws of Chance” was created by dropping torn pieces of paper on the floor. “Dada,” wrote Arp, “wished to destroy the hoaxes of reason and to discover an unreasoned order.”

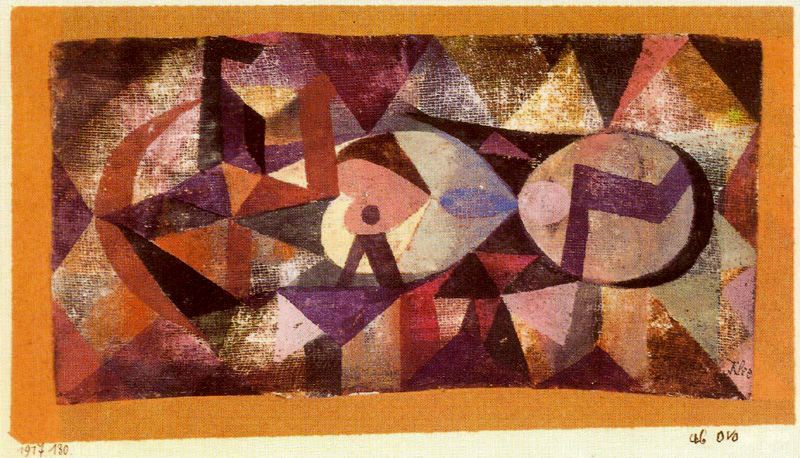

Made during Klee’s time in the German Army.

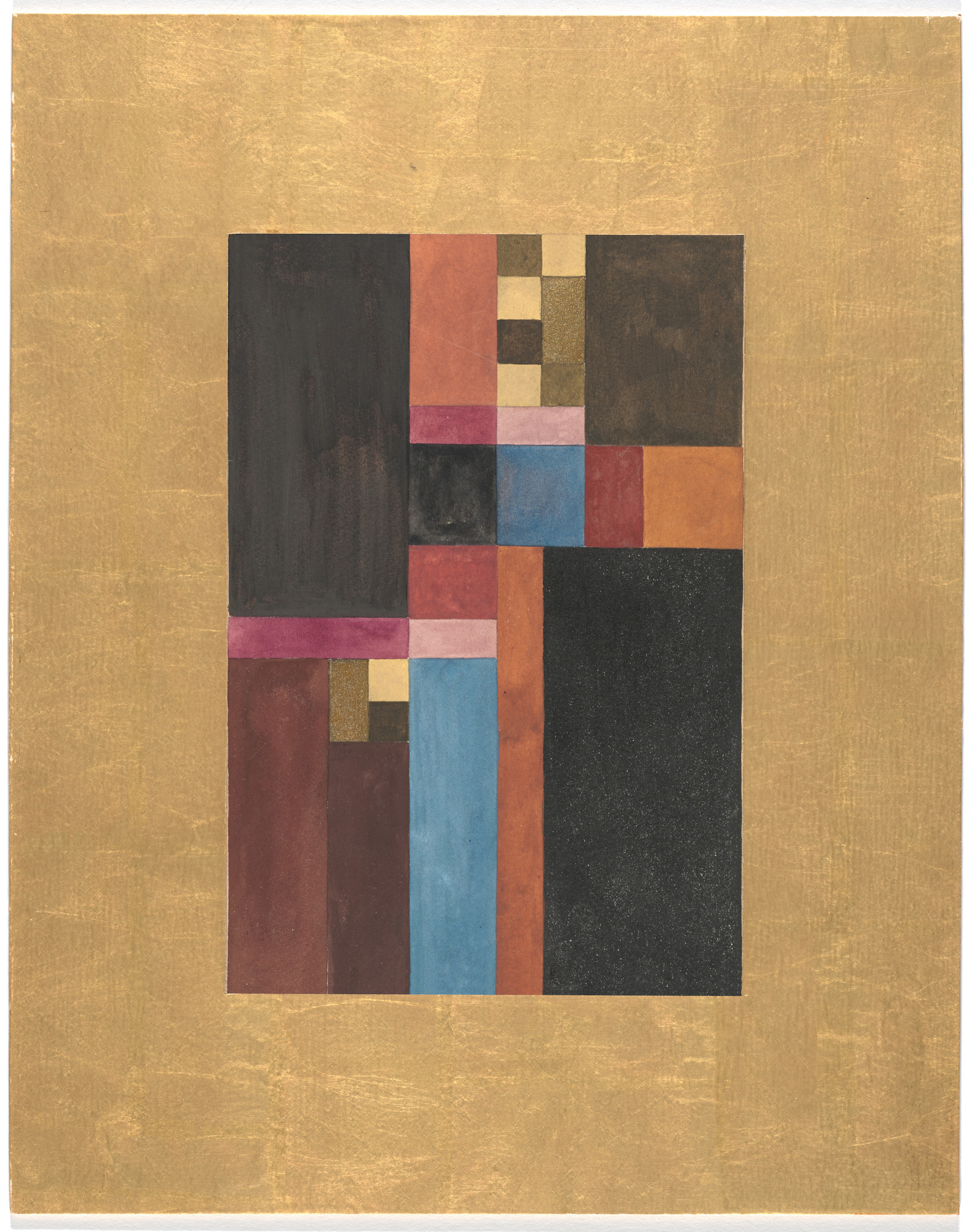

Van Doesburg’s style of painting changed in 1913 after he read Kandinsky’s autobiographical Rückblicke — which led him to realize that there is a more spiritual level in painting that originates from the mind rather than from everyday life; and that abstraction is the only logical outcome of this. In 1915 he came in contact with the works of Mondrian, in which he found further evidence of his ideal: complete abstraction of reality (which is to say, total rejection of visual reality). Van Doesburg got in contact with Mondrian, and together with several other artists they founded the magazine De Stijl in 1917. The source of art, they argued, was a “universal consciousness” out of which would come “universal harmony.” Composition became a linear exercise based on squares and cubes, emphatically structured in right angles.

MORE RADIUM AGE SCI FI ON HILOBROW: RADIUM AGE SERIES from THE MIT PRESS: In-depth info on each book in the series; a sneak peek at what’s coming in the months ahead; the secret identity of the series’ advisory panel; and more. | RADIUM AGE: TIMELINE: Notes on proto-sf publications and related events from 1900–1935. | RADIUM AGE POETRY: Proto-sf and science-related poetry from 1900–1935. | RADIUM AGE 100: A list (now somewhat outdated) of Josh’s 100 favorite proto-sf novels from the genre’s emergent Radium Age | SISTERS OF THE RADIUM AGE: A resource compiled by Lisa Yaszek.