OFF-TOPIC (62)

By:

June 22, 2024

Off-Topic brings you over-the-transom, on-tangent essays, dialogues and subjective scholarship on an occasional, impulsive basis. For this summer of our discontinuity, a conversation of voices thrown across years and echoed in the present…

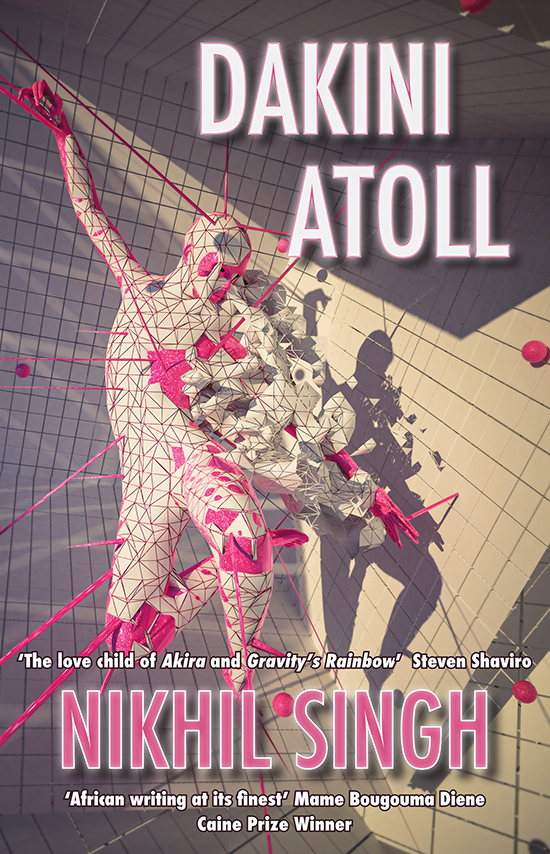

We think we move through time, but time comes toward us, its vibrations felt before we build the strands that connect out to it, the chosen possibilities moving in to fill our empty center of the universe. Nikhil Singh’s psychic notations hop the nexuses of that endless weave, with a glance closing the distances that converge on our single spinning Now. If observation affects what is viewed, then vision attracts what is imagined; an illusion is just a reality you haven’t believed yet. Singh’s new novel Dakini Atoll spools from the unfolding goddesshood of pop divas, the synaptic lightning captured in ultrathin glass planes, the transformations that are our only true tradition, to radiate a tale of shadowy operatives, corporate apostles, transcendent celebrity, ecological collapse and ecstatic renewal, as secret societies plan to help humanity outlive its disasters and rogue innovators scheme to have people outgrow their humanity, the protagonists’ purposes crossing and spiraling, with the entire world and its pandemic-wracked, pop-addicted masses the laboratory for metamorphosis and test-market for salvation.

The raw-feed narrative networks your brain to an internal blockbuster of vibrant post-end-times cityscapes in both their renegade arts enclaves and zombie warzones; proxy-consciousness robot contests in breathtaking desert locales; international intrigues with mercenaries and sleeper agents in fabulous beach resorts and fabricated small-town environments; pilgrimages in newly-minted massmarket faiths and rituals in ancient-rooted sects of mysteries and monsters; the scary immensity of the endless fouled oceans and the sublime glacial blank slate and new precipice of space.

Ostensibly a sequel to Singh’s Club Ded but not so much based in it as haunted by it, you’ll be rewarded with recognition if you read the previous book, and just as stimulated by this one’s uncharted territory if you didn’t; we are proceeding into an epic era with missing pages or no manual at all, and the story we collectively write next must profoundly stand alone. Dakini Atoll provides new characters to never forget, in a serially renewing context; the closest thing to a heroine, known to her longest-standing fans and disciples as Delilah, herself goes by and through at least seven names, like the incarnations of a product and the rollouts of the gods. If none of this makes sense then you’re beginning to understand, and I shared signals across the nervous net of the global moment in autumn 2023 with Singh, strung between Johannesburg and New Jersey, to unravel some meanings and tie the next knots…

HILOBROW: There’s a perennial panic about whether mass entertainment will pacify us with distraction or, worse, disable us from distinguishing between fantasy action and real-world consequences. We’re putting this conversation in a time-capsule — as we exchange messages, circa October 2023, much of the world seems quite capable of discerning that rubble on a news-screen means real-life corpses and that governments’ narratives are not average people’s realities. But I guess media has always been in a race with itself between educating and anaesthetizing us. In Club Ded, big-budget superhero-sequel cinema was not just a perennially good place to sink abominable behavior and corrupt fortunes into, but an effective front for weird social experiments and human-augmentation spinoff technology. In Dakini Atoll, holographic virtual-reality TV is the house-of-mirrors medium for grand-scale reshaping of civilization and genetic reengineering, in which billions are enthusiastic yet unaware collaborators. Is each era of mass expression — ancient myth, classic movies, modern simulated experience and shared delusion — an opiate imposed on the many by the few, or a more mutual, instinctive loop to prime our minds for possible futures and unperceived potential?

SINGH: It might be something of a “Western” trope to come to view mass-media as a controlling force. Certainly, in America and other parts of the “First World,” I witnessed a sheepy over-reliance on news sources and entertainment programming. A sort of unquestioned mode of ethics built into consumption. But really, this is all illusory. Coming from the “Third World” and having spent my entire schooling career under Apartheid, I come from a distrustful mindset which strips communications monopolies down to basics and looks at the structure of information dispersal and how it can be used/abused individually. The internet used to enjoy complete freedom before corporate interests destroyed net neutrality between 2013/16, completely obliterating online freedoms in favour of institutional control. Dakini Atoll looks at the emergence of new, semi-organic “weapons of mass-instruction.” The core of imagining itself, removing cuffs of corporate over-watch (completely). Looking at communications systems in terms of their basic function and what they can achieve in the hands of the masses. It’s a slow process — within the narrative, linked to Delilah’s awakening to her influence and reach. A sort of punk approach to mass information dispersal. Because in Club Ded, the mode is still “expression” — movies, from summer blockbusters to experimental film-making. Dakini steps beyond media as a means of expression. The holographic sphere as a mirror world — a place to be inhabited. Initially, it is cancered with the same corporate interests at work in the previous world, but as Delilah’s power waxes, these outside controlling forces begin to wither on the vine. A new perceptual paradigm begins to emerge.

HILOBROW: In Club Ded most of the protagonists played action heroes on-screen, while in Dakini Atoll most of the protagonists… play them in all-too-real life. We think of soldiers, mercenaries, assassins, spies, enhanced humans and evolved mechanical beings as the stock casts of pulp and genre, yet there are more and more freelance stateless killers, chemically boosted athletes, and possibly rogue artificial consciousnesses occupying our actual world. The perpetually at-risk warrior women, unhinged highest-bidder mad scientists, armies and gangs reorganized into tribes and cults, lab-cultured species, and human/machine mergers throughout Dakini show us how frightening and not-fun our popular fantasies, technological ambitions, and even fitness culture could become, and how fast. Is Darwinian violence the inevitable currency of human interaction? Or just our excuse to be uncivilized? Is pain always the cost of new birth, or just the only way we’ve ever learned?

SINGH: Again, there’s a bit of a Third World divide. I grew up somewhat familiar with resistance fighters, soldiers, assassins, spies and mercenaries. My father’s family was involved in resistance against the apartheid government — some relatives had been exiled to the UK, hence my on-and-off childhood in London. One of my school friends’ dads was a sniper, another a colonel. My brother was trained in martial arts by another sniper. Later, clubbing — many in the party crowd were ex-Angolan war. It’s just part of being South African, I guess. My generation grew up thinking we would fight in Angola (conscription was mandatory and thankfully abolished long before I turned 18 — phew). But much time at school was spent with classmates discussing what we would do in the army if we couldn’t get out of it. My whole plan was to become a helicopter pilot. By age 12 I was building scale models, learning about their engineering in preparation, reading books like Chickenhawk (memoir of a Huey pilot in Vietnam) and watching Vietnam movies — thinking that was kind of what I was in for. So, it might be a South Africanism — but these types were never really far from reality. To the point where it became a driving force not to be in that world. Nothing romantic about being conscripted to kill by an institution. Certainly, many of my acquaintances in that sphere ultimately moved towards the arts — writing, visual mediums or music (mostly music). But to address the question more directly — the book does center around this concept of inbuilt violence — how it seems to be inseparable from the human condition. We have operatives in the book who are working toward utopian ends, but are hypocritically engaged in bloodshed — often against their will. Currently, in the world (the “First World” mostly), there is a prevailing air of morality around ideas of technological advancement, which is divorced from the reality of human nature. We are naturally dualistic. Life is not polarized into “good” and “evil.” The book explores the pitfalls that arrive with augmented power in a realistic way. How it invites corruption. The personal and global toll of quixotic power brokerage. After all — what is civilization, if not a lie? The most peaceful communities are still stone-age-culture tribes living in harmony with their natural environments for thousands of years. “Civilized” modern living is supported by a toll of endless bloodshed, corporate parasitism, exploitation etc. etc. It’s a wonderfully utopian ideal — but unsustainable without its shadow side. The book gets into these questions in a very direct way with the Angels [a system of agents guiding global change subtly and otherwise — ed.]. Direct responsibility.

HILOBROW: This book’s crisp sentences go in on a cortical level; a phenomenal amount of sensory information and narrative/expressive context is condensed and conveyed. Almost like a mosaic of multiple pulses of understanding, short lines of code, rapidly configuring even though they seem like one fragment at a time. Do you write in these bursts, or draft it more long-form and then parcel it down? And if it is written burst-by-burst, do you need to stay inside the process for long stretches for it to fill in, lest the components de-cohere and you have to start over like a griot interrupted recounting centuries of narrative — or is it more that the pieces come to you individually, not necessarily in sequence, and connect like tectonic plates over time?

SINGH: Club Ded was a bit of a patchwork quilt, finding a style that I thought would suit the mass information spectrum — arriving at a sort of text message meets Haiku mode. So, in Club Ded, parts were written in long-form, then “translated.” Other sections directly, as is. But, in Dakini, the style had already been firmly baked in. Actually, I think I broke all sorts of personal records writing it. Because the style not only speeds up readership, but authorship as well! Well, in my experience of it, at least. I wrote the entire book — from inception to delivery (it was barely edited — just some punctuation) in a month and a half. I was writing a chapter a day at its peak. In fact, the “Little Brother” chapter was written, in its entirety, on my birthday — on 22nd Dec 2022. I make no physical notes — employing a memory method I came up with that uses limbic recall in half-awake states. So, in a way — these books were also (re)writing me lol.

HILOBROW: Dakini is ostensibly set in “the future,” but we’ve spoken before about how the future keeps slipping behind us, and a present-tense narrative for a mindblowing story seems utterly natural in a world that surprises us daily. We can see the realities of Nikhil Singh, and of other Afrofuturist fiction, coming; we will recognize them when they do; and we suspect they are already fading up into place (all the more so for “cyberpunk,” which at this point is almost a vintage future). In the Club Ded series it almost feels like multiple folds of simultaneous time gathering — as if Dakini’s narrative is an alternate branch from Ded’s core story, rather than a strict successor to it. Are all our possibilities bunching up against an impermeable Now?

SINGH: I think it’s important to try to get back to the natural fluidity of time in literary fiction. It was a popular “style” with many writers for a while. Look at Easton Ellis and DeLillo for example. But, in this slave new world of “genre-fication” — science fiction/speculative fiction/whatever it’s called by academics now has slipped into a sort of prefab crack in time, dictated by gaming mindsets, commercial cinema and academic methodology — which is usually geared toward sales. So, time is simply viewed as another set-piece — something to “drive a plot onward.” I would rather drive a plot inward. Perhaps even destroy plot entirely — or, as you say, graft branches off it that grow in unexpected ways. In reality, our sense of time shifts constantly — it slows down, speeds up, becomes formalized, is dictated, or distorts, once freed from constraint. I prefer characters to inhabit “real time” — which, in many ways, is no time at all. So, everything is in the moment for the reader — who is absorbing a primal present moment — which acts almost as a lens, through which the past and future can be viewed. Initially, before Club Ded, I favoured past tense — things read better, there is a sense of literature in past tense. But it simply didn’t suit the immediacy of the Club Ded realm — which seeks, of its own accord, to break the fourth wall. Not over-dramatically, but just enough to evoke a sense of “futuristic immediacy.” Writing in present tense is very difficult. I find most examples to be quite simplistic and action-oriented. But I wanted a textured, fluid document that slips between interior and exterior — so, it took a while to hone this style. But once the coding was complete — I found it’s possible to weave a narrative that calls the impermeable now into question and interrogates the idea of perceptual time at its root. In this way — all possibilities become valid, in a post-post-modern spectrum.

HILOBROW: Related to that, to what extent do you feel pulled along into the future, or phasing in and out of place with fictional interpretation? Because the sense of immediacy is compounded with a brief appearance of you yourself as a character within Dakini.

SINGH: Well, I enjoy very much the post-modern aspect of narrative self-insertion — but, only in a wholly impersonal way. As a sort of Cheshire Cat. It’s very Borges, or Pessoa. Even Easton Ellis inserted himself into Lunar Park — though, in that case, the entire narrative wrapped itself around his doppelganger, I just wanted a small step-in — to create a narrative foil, wherein I could question certain plot points — almost as a joke — and spend time with my characters one on one. I think this sort of practice can succeed if it’s not all terribly self-indulgent. I wanted a little flavour of the “meta” in the book, but not enough so that it was displacing the here and now of the narratives. The insertion, as you point out, does afford me a unique placement four-dimensionally — where I can co-exist in two universes at once (within this universe!) by co-habiting a fictionalized realm and the realm wherein said fiction is fictionalized. Once I had the concept, I couldn’t really not do it lol. I had my reservations — but the muse (which, in this case, was I, myself, (and I) lol) led me to a somewhat satisfying literary promontory, prompting possible future routes — where narrative might expand four-dimensionally, with a bolder flavour of post-modernism…

HILOBROW: It’s not giving away too much to mention that Dakini centers on our own current world’s idea of a “web,” in both its colloquial usage and conceptual implications, then makes it astoundingly literal, and then multiplies its associations and reconverts it to a vastly metaphysical metaphor. Since you’re a visual artist too, do you sometimes build narratives from a design/geometric base rather than a verbal one?

SINGH: Not really — the narratives arise from a very formless place. Almost as dreams. In fact, I do a lot of the plotting in the moments between waking and sleep. Memory works differently then. You can sort of backflip into dreaming and “test-drive” scenarios. Also, you can look at larger narratives with very clear precision. So, essentially, I suppose I prefer to plot subconsciously. After all the mind is often an enemy to creativity. Dream logic is superior. I would work out most of the Dakini events whilst walking — mostly barefoot in a primeval mangrove forest or at the lagoon beach. Club Ded was written in so many cities, I lose count. Partly in Hampstead, Nairobi, a cabin in Sweden. Some in Cape Town, some in the oldest weed café in Amsterdam’s red light district (where my ex worked). But Dakini was written in Umhlanga in Zululand. I would walk in the forest near dark and till the fireflies came out. Then type all night. I had to hold the structure mentally (since I make no notes). But, it’s a good way to do it because then the book is a living thing. Also — I felt it was in keeping with the novel’s preoccupation with neural structures. The characters are alive — they can choose their direction. I allow characters to make their own decisions. See where they take themselves. Allowing them to live — following and notating them — as though they were holograms and I were among them — another reason why I chose to manifest as a cameo in their universe. As above so below.

HILOBROW: The sense of place is vivid and of atmosphere precise, whether in the book’s settings of apocalyptic NYC or Joburg streets, dystopian post-boom Long Island City, gentrifying ghost-town London, ultrarich desert and island idylls, garrisoned Eastern Europe, bizarre fairy-tech bunkers and compounds, or the living palimpsest of the mythic Chelsea Hotel. One planned (schemed) community is deliberately built to look a century older than it is, and while speculative and spiritual concepts of Japanese culture pervade the book, neither the book nor, I find, you yourself, have ever set foot there geographically. Is impression more reliable than observation?

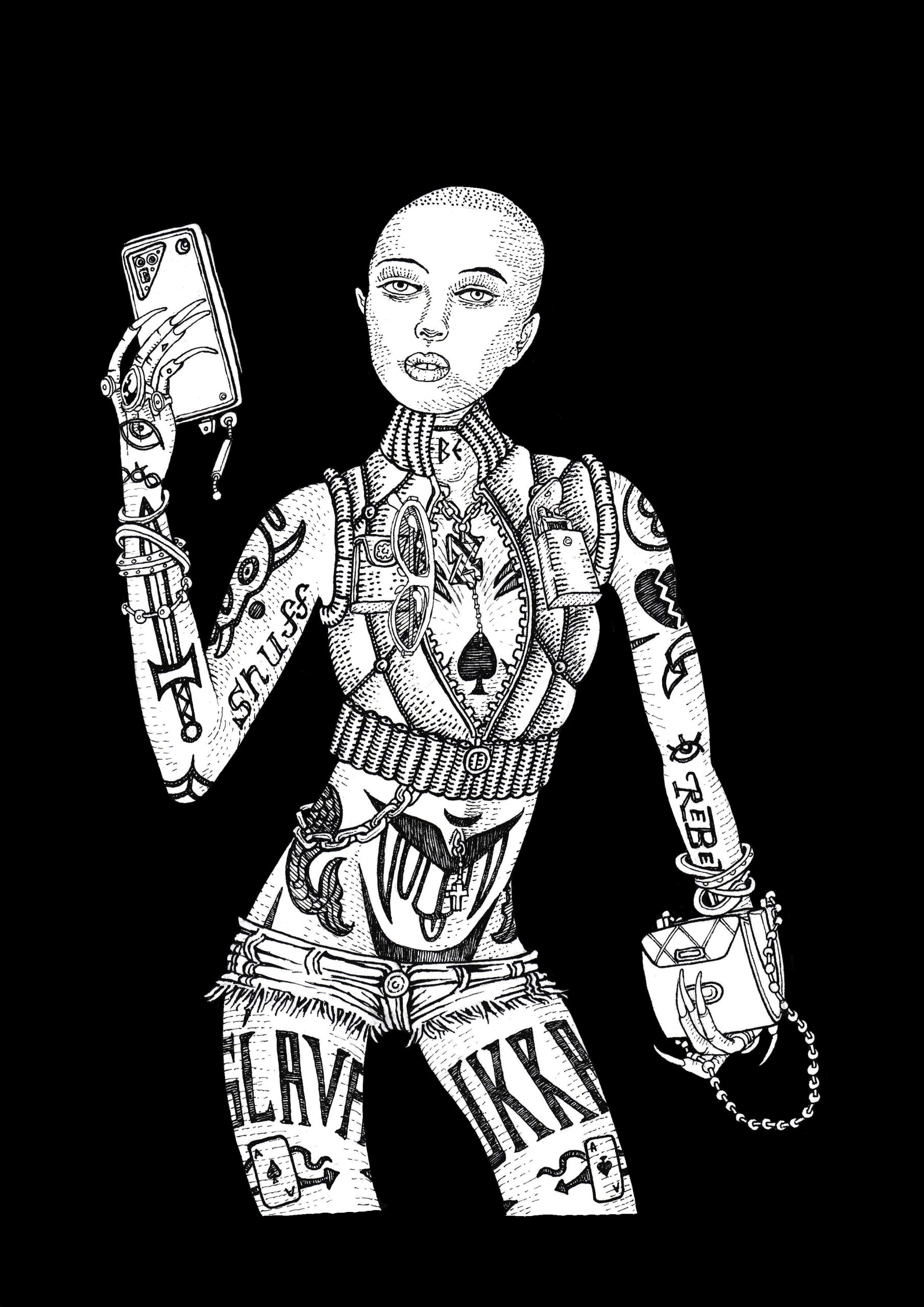

SINGH: I think it depends on the place. Some places are more real than others — individually speaking. For example, I find my literary and filmic sense of New York to be a lot more real than the reality of New York. I certainly didn’t have a sheltered experience of New York — but, even so, it simply didn’t live up to the memory palace I had constructed from countless books, movies and music albums. However, London is a different beast. London’s been a city since the stone age and you can really feel its history when you are within its maze — “something old and choked with flowers.” Even NYC’s native population drifted in relatively early in comparison to early European habitation. So, even in its oldest context — NYC is still a “modern” place and has that feeling — for me, at least. So, I think it’s a question of what resonates personally and what doesn’t. Apparently Hergé didn’t travel at all — though his Tintin drawings really capture a spirit of place. I believe in writing what you know — but really, sometimes, you can know a place without being there. With Johannesburg — it really has to be experienced to be understood. It’s such a visceral city — yet, also quite ethereal in its own strange way. I’d boycotted Jozi for years because it just seemed so nightmarish, but after living there I was bewitched by its underlying enchantments. After all — 70% of the world’s gold comes from there. It’s truly a power place. But looking at it — it can really appear like hell on earth in some ways. So, in that case, I feel it was necessary, to live it. But, New York, I feel I could have captured just as accurately without having lived there. Japanese culture, on the other hand, for me is more about the approach to culture itself. There’s a certain formalized way of approaching aesthetics that I’ve drawn from my Japanese reading and film consumption. For me, Japan is less about Japan, than it is about an approach to aesthetics. I’m always surprised at how deeply I’ve been affected by Japanese culture. It finds a place in almost everything I’ve written — without me expecting or planning it. Seikichi, for example, is a tribute to his namesake character in Junichiro Tanizaki’s Irezumi. Yet, even this simple cameo swelled, to eclipse the entire narrative with Seikichi’s personal aesthetic — with very few appearances!

HILOBROW: A few characters from Club Ded who theoretically could be here are absent from Dakini Atoll… Ziq especially feels like he made a separate peace. At the end of the first book, he goes off-grid, but in a meta sense it’s as if he’s gone off-story. Is it possible for us to escape the texts we were written into?

SINGH: Yes, Ziq, out of all the characters certainly walked off-camera into the void. I described Club Ded as an existential novel — because it is exactly that. Embodied in Ziq’s arc. Existentialism was born in Africa, from an African — lest we forget Camus was born on African soil. That narrow tightrope — life on the edge of the void is prevalent. So, Ziq, I feel exited at a cosmic level. Jennifer still exerts a huge, unspoken influence. Unintentionally — her ghost haunts the narrative at various, unexpected points. Looking at these two — who are also entwined inextricably — it’s perhaps possible to answer your question. Ziq’s entire philosophy of the first book — this “it is written” thing — is something he managed to rewrite — or did he? So, I have to say, yes it’s possible to escape. Though, as soon as you have succeeded in doing so, escape is written. Then you are back at square one.

HILOBROW: Dakini proceeds in directions I never could have imagined from Club Ded; it covers a span of time and transformations that are hard to conceive of, and now I sense there’s a third book to come. It seems the world never ends no matter how hard we try. Is that something to rejoice in or mourn?

SINGH: Club Ded was a literary experiment — it came out of various inspirations, chiefly The Alexandria Quartet — which Durrell described as science fiction in the afterword of the Faber collected edition. Which would make it a precursor to Afrofuturism — in a sense I relate to, personally. Dakini Atoll is a streamlined expansion into imagined futures — straying from the neorealist arenas of Club Ded, into more far-flung regions and dizzying hypotheticals. Though, I would say the pacing was markedly different. Club Ded is a slow kaleidoscope — Dakini Atoll a burning maelstrom. A third book, would have to somehow showcase both paces — yet, in each, an acceleration. A slow burn — building to a frenzied cascade. I also think the medium of time itself would have to come to the forefront. Time is a kind of character in these two books — how it alters perception, how we are prisoners of time, how time changes its language — over time. I feel the “meta,” post-modern elements planted in both books would have to bloom into a hitherto unimagined time-plant. Something that discreetly involved the reader into its matrix, to sketch a universal point of view. I sense possibilities — perhaps from within the story itself? After all, I am somewhere in the future narrative — as an unwritten character — throwing coded paper jets back to this moment. Hopefully my author self will be able to transcribe the whispers of my future character — into something “already written.” An oracular function? Look — I’m already speaking as though a third book is complete. Perhaps it is, ha ha….

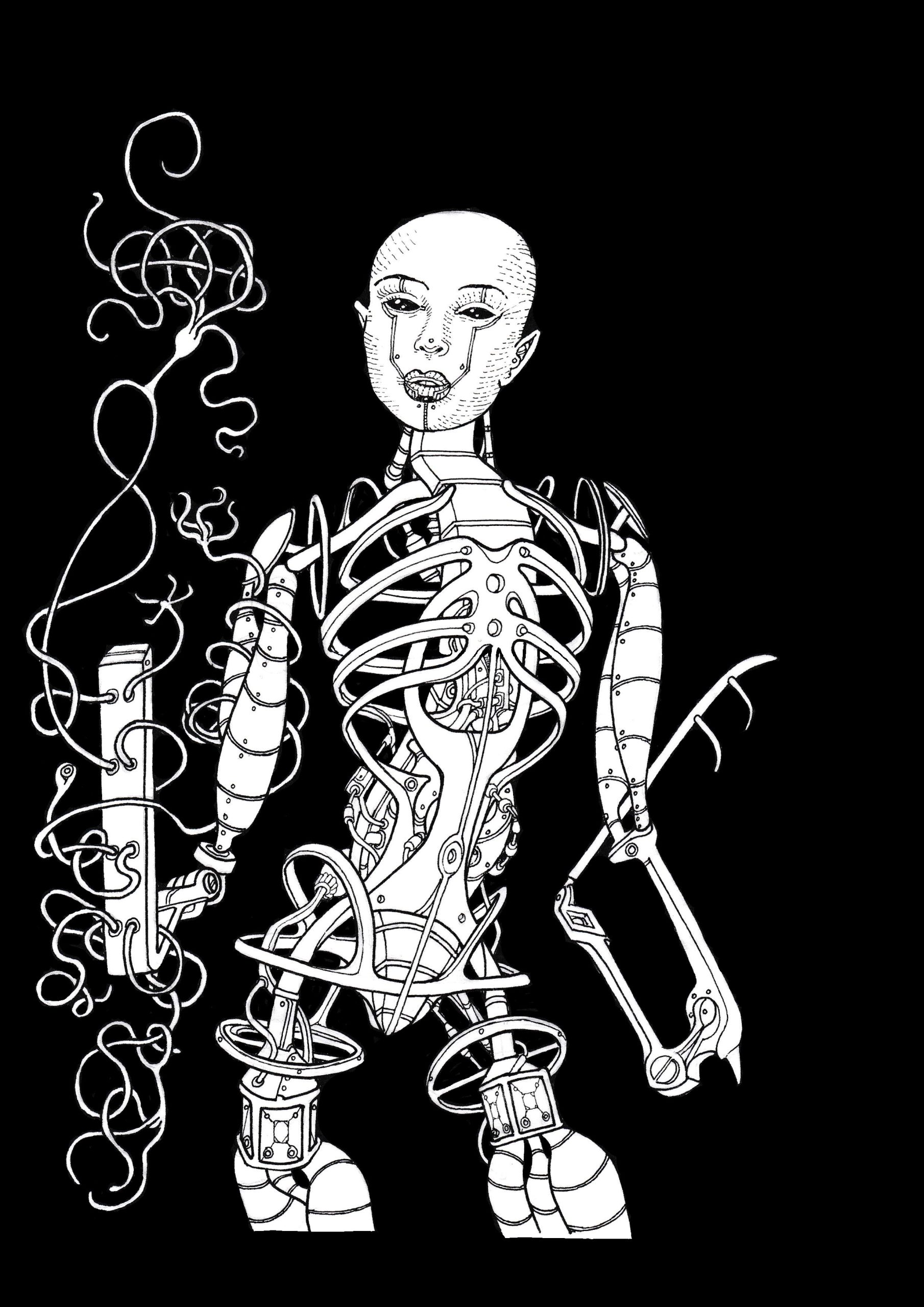

[Images (top to bottom): Dakini cover by glitch auteur Elena Romenkova; original drawing by Singh for the Illustrated Hard Back Edition; memento mass murder; dramatic readout from Dakini (one per week uploading ’til the book’s release); stills from a dance of creation and destruction self-shot by the novelist at the Chelsea Hotel; original drawing by Singh for the Illustrated Hard Back Edition; out the window of the Chelsea (still from a Singh video); screenshot from Irezumi (1966); more recitation from the soon to be]

MORE POSTS by ADAM McGOVERN: OFF-TOPIC (2019–2024 monthly) | textshow (2018 quarterly) | PANEL ZERO (comics-related Q&As, 2018 monthly) | THIS: (2016–2017 weekly) | PEOPLE YOU MEET IN HELL, a 5-part series about characters in McGovern’s and Paolo Leandri’s comic Nightworld | Two IDORU JONES comics by McGovern and Paolo Leandri | BOWIEOLOGY: Celebrating 50 years of Bowie | ODD ABSURDUM: How Felix invented the 21st century self | KOJAK YOUR ENTHUSIASM: FAWLTY TOWERS | KICK YOUR ENTHUSIASM: JACKIE McGEE | NERD YOUR ENTHUSIASM: JOAN SEMMEL | SWERVE YOUR ENTHUSIASM: INTRO and THE LEON SUITES | FIVE-O YOUR ENTHUSIASM: JULIA | FERB YOUR ENTHUSIASM: KIMBA THE WHITE LION | CARBONA YOUR ENTHUSIASM: WASHINGTON BULLETS | KLAATU YOU: SILENT RUNNING | CONVOY YOUR ENTHUSIASM: QUINTET | TUBE YOUR ENTHUSIASM: HIGHWAY PATROL | #SQUADGOALS: KAMANDI’S FAMILY | QUIRK YOUR ENTHUSIASM: LUCKY NUMBER | CROM YOUR ENTHUSIASM: JIREL OF JOIRY | KERN YOUR ENTHUSIASM: Data 70 | HERC YOUR ENTHUSIASM: “Freedom” | KIRK YOUR ENTHUSIASM: Captain Camelot | KIRB YOUR ENTHUSIASM: Full Fathom Five | A 5-part series on Jack Kirby’s Fourth World mythos | Reviews of Annie Nocenti’s comics Katana, Catwoman, Klarion, and Green Arrow | The curated series FANCHILD | To see all of Adam’s posts, including HiLo Hero items on Lilli Carré, Judy Garland, Wally Wood, and others: CLICK HERE