RADIUM AGE ART (1916)

By:

June 16, 2024

A series of notes regarding proto sf-adjacent artwork created during the sf genre’s emergent Radium Age (1900–1935). Very much a work-in-progress. Curation and categorization by Josh Glenn, whose notes are rough-and-ready — and in some cases, no doubt, improperly attributed. Also see these series: RADIUM AGE TIMELINE and RADIUM AGE POETRY.

RADIUM AGE ART: 1900 | 1901 | 1902 | 1903 | 1904 | 1905 | 1906 | 1907 | 1908 | 1909 | 1910 | 1911 | 1912 | 1913 | 1914 | 1915 | 1916 | 1917 | 1918 | 1919 | 1920 | 1921 | 1922 | 1923 | 1924 | 1925 | 1926 | 1927 | 1928 | 1929 | 1930 | 1931 | 1932 | 1933 | 1934 | 1935 | THEMATIC INDEX.

First year of Dada.

Soon after arriving from France in 1915, Marcel Duchamp and Francis Picabia met American artist Man Ray. By 1916 the three of them became the center of radical anti-art activities in the United States. American Beatrice Wood, who had been studying in France, soon joined them, along with Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven. Arthur Cravan, fleeing conscription in France, was also in New York for a time. Much of their activity centered in Alfred Stieglitz’s gallery, 291, and the home of Walter and Louise Arensberg. New York Dada lacked the disillusionment of European Dada and was instead driven by a sense of irony and humor.

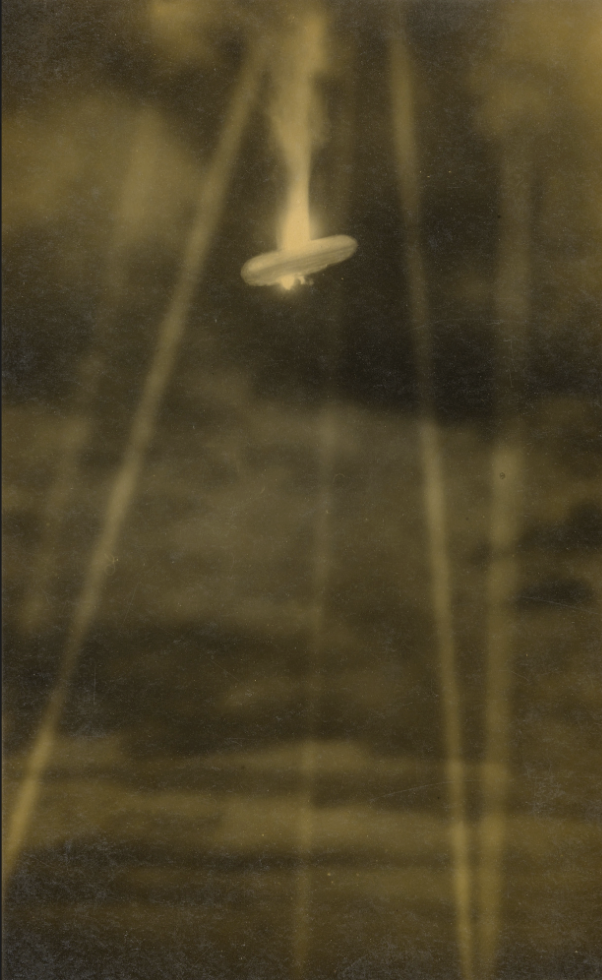

Paris is bombed by German zeppelins.

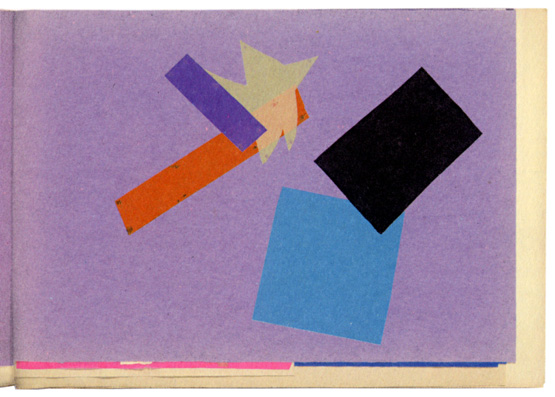

Aleksei Kruchenykh publishes Universal War in Petrograd at the beginning of 1916. Despite being produced in an edition of 100 of which only 12 are known to survive, the book has become one of the most famous examples of Russian Futurist book production.

The Easter Rising occurs in Ireland.

July 1–November 18 – Battle of the Somme. More than one million soldiers die.

The Cabaret Voltaire is opened by Hugo Ball and Emmy Hennings in the back room of Ephraim Jan’s Holländische Meierei in Zürich. Those who gather here include Marcel Janco, Richard Huelsenbeck, Tristan Tzara, Sophie Taeuber-Arp and Jean Arp. Tzara founds the movement Dada; it will spread to Paris, Berlin and New York. Dadaists reject bourgeois values of visual art; they will invent what we know as Performance Art, Happenings, and Conceptual Art.

As of 1916, Mondrian began doing away with subject matter entirely in favor of what he increasingly felt was the irreducible structure of the world: a grid of perfectly parallel and perpendicular lines, comprised of his crosses, now connected. A semiotic vision.

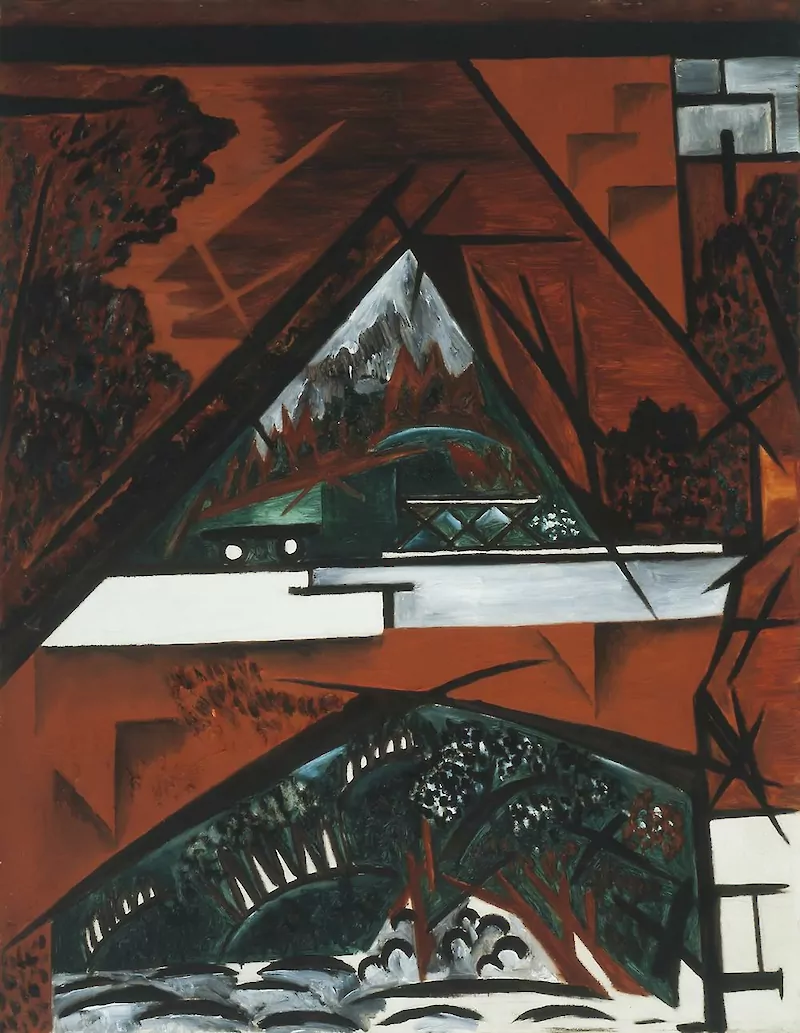

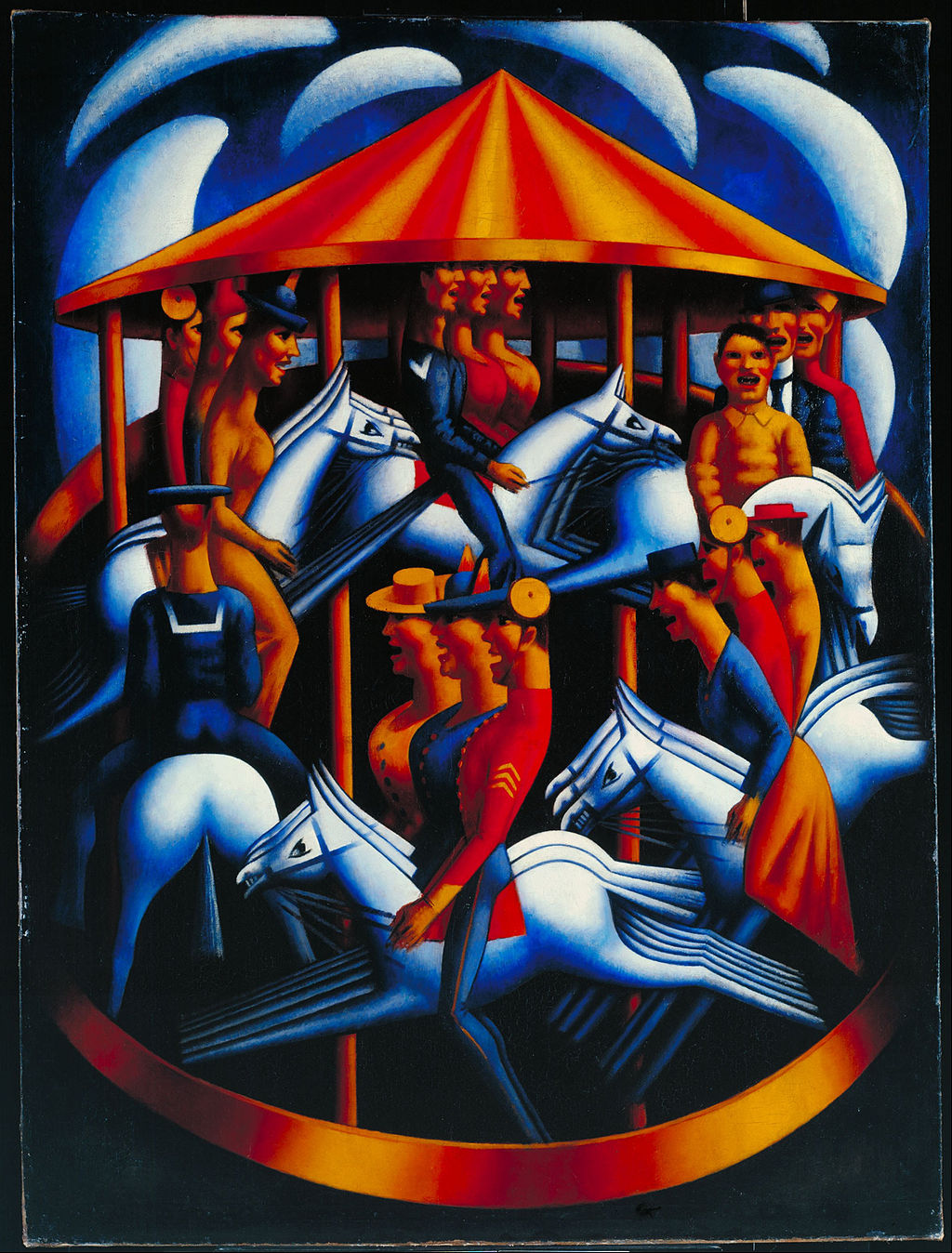

Precisionism was a modernist art movement that emerged in the United States after World War I. Influenced by Cubism, Purism, and Futurism, Precisionist artists reduced subjects to their essential geometric shapes, eliminated detail, and often used planes of light to create a sense of crisp focus and suggest the sleekness and sheen of machine forms.

Ferdinand de Saussure’s Cours de linguistique générale is collected posthumously and published.

Also see: RADIUM AGE: 1916.

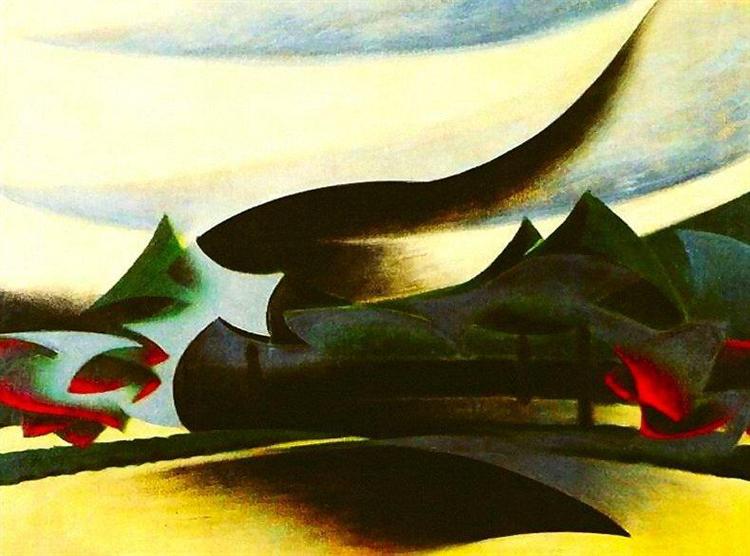

O’Keefe uses a “fetal form as a symbol of cosmic creation,” writes Pepe Karmel in Abstract Art: A Global History. He notes the thematic similarity to Kupka’s The Beginning of Life (c. 1900).

Léger’s experiences in World War I had a significant effect on his work. Mobilized in August 1914 for service in the French Army, he spent two years at the front in Argonne. He produced many sketches of artillery pieces, airplanes, and fellow soldiers while in the trenches, and painted Soldier with a Pipe (1916) while on furlough.

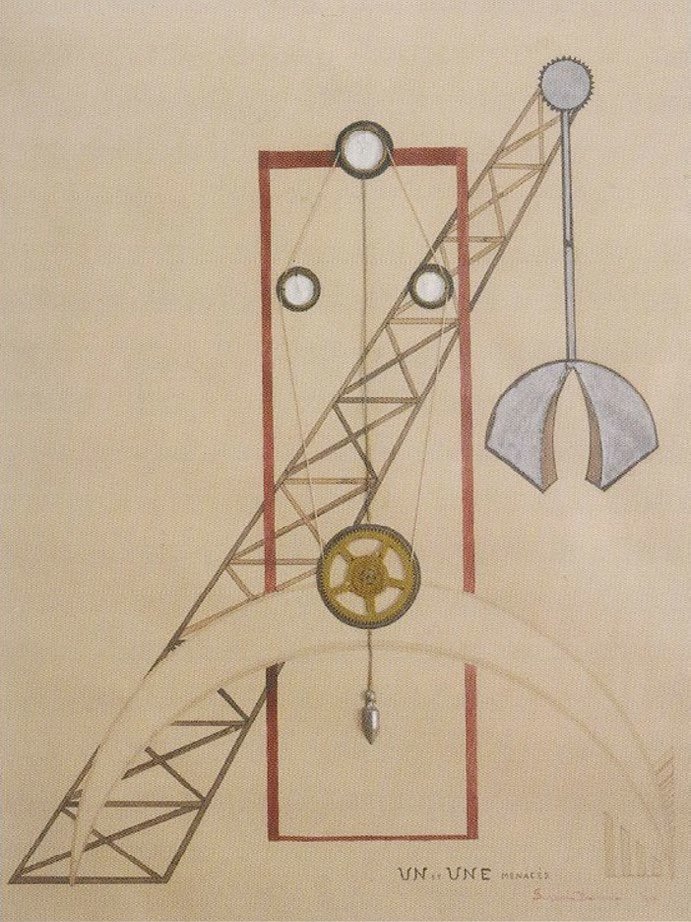

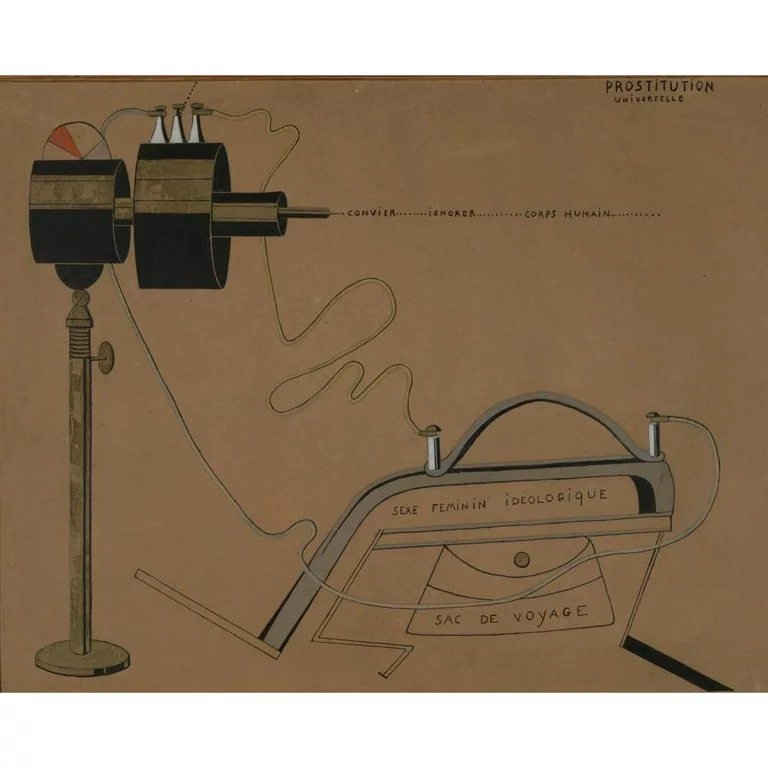

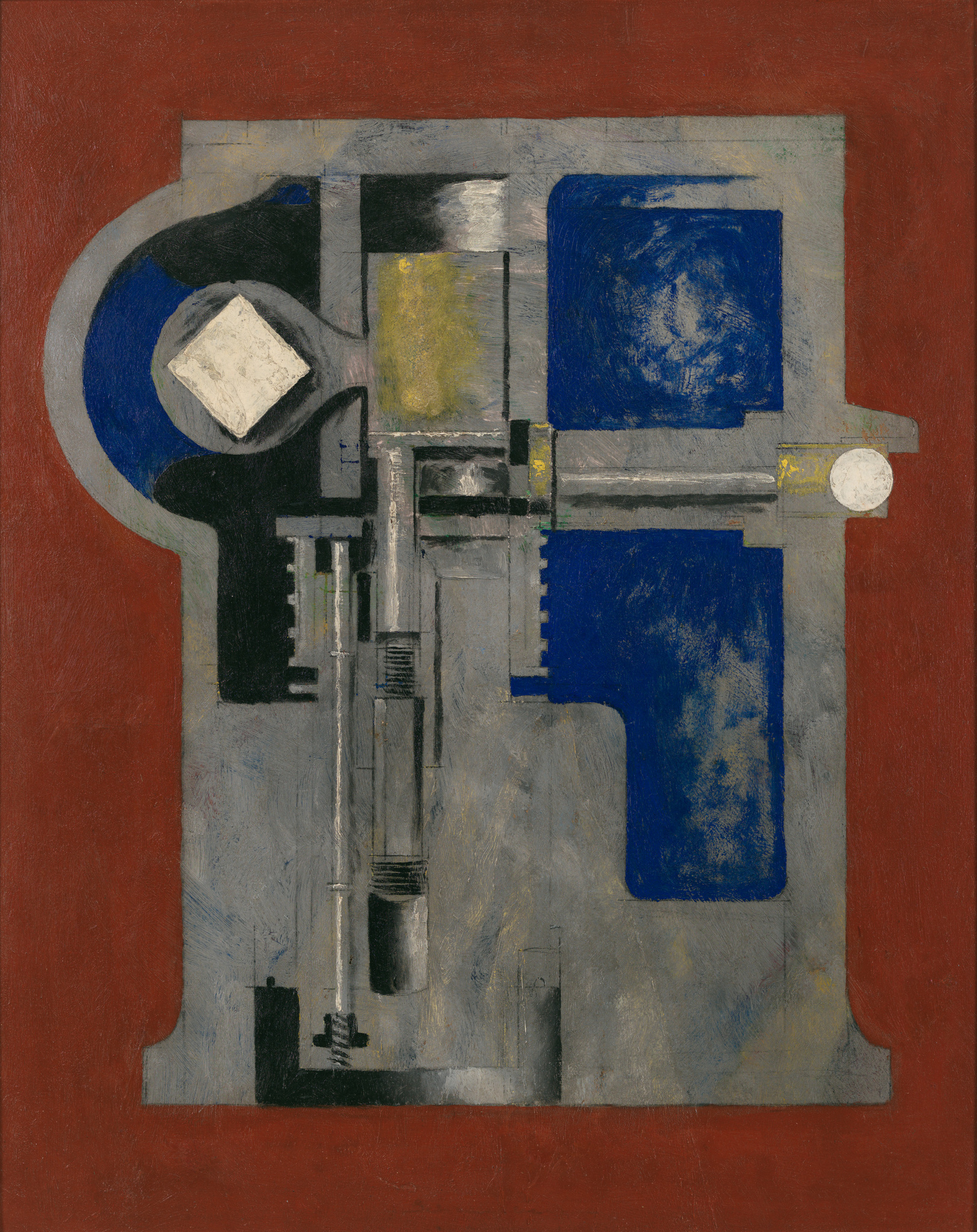

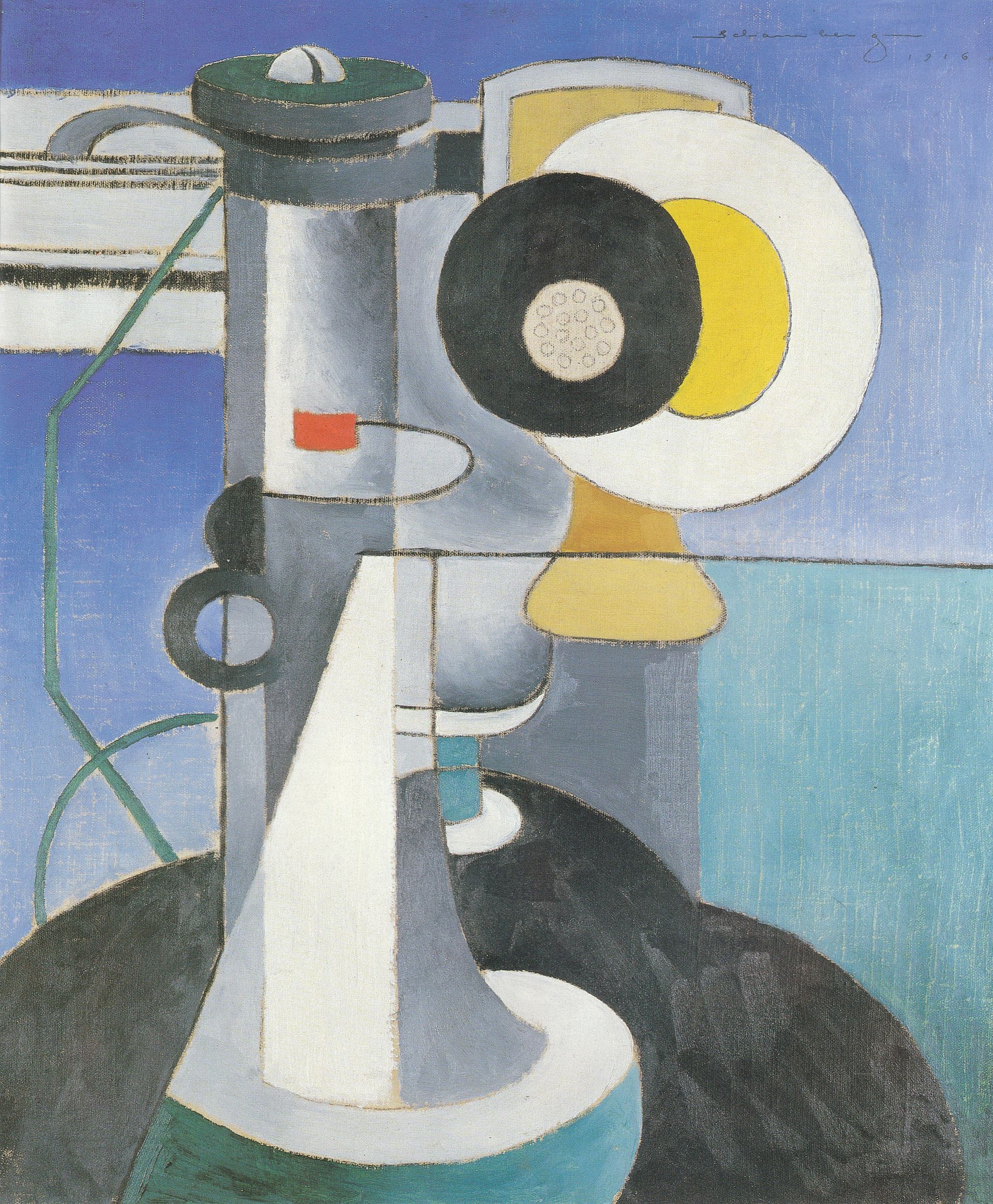

From the Yale Art Gallery’s website: “In the 1910s, the French avant-garde artist Francis Picabia made a series of playful, enigmatic works combining machine imagery with allusions to human sexuality. As opposed to the triumphalist narratives of technological progress that were widespread in the early twentieth century, Picabia’s ‘erotic’ machines appear in a state of whimsical dysfunction: they seem to reflect the foibles of human nature, rather than transcend them. Picabia’s images gently mocked ideologies of masculinist militarism at a moment when Europe was engulfed in the mechanized violence of the First World War. […] The words trailing across this image read, ‘invite … ignore … human body,’ a message of failed desire and frustrated intent rather than of technological mastery.”

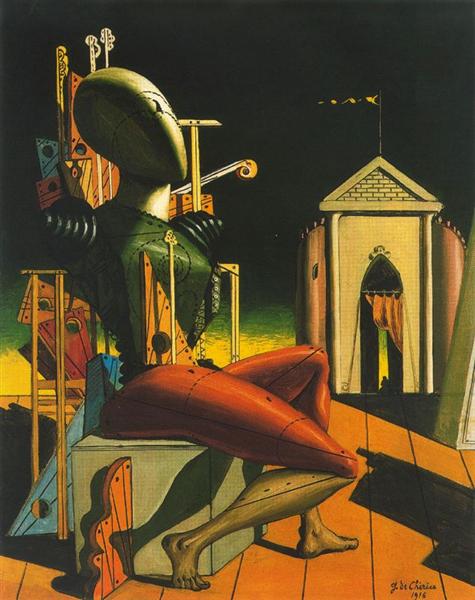

One is standing and the other sitting, and they are placed among various objects, including a red mask and staff, an allusion to Melpomene and Thalia, the Muses of tragedy and comedy. The statue on a pedestal in the background is Apollo, leader of the Muses.

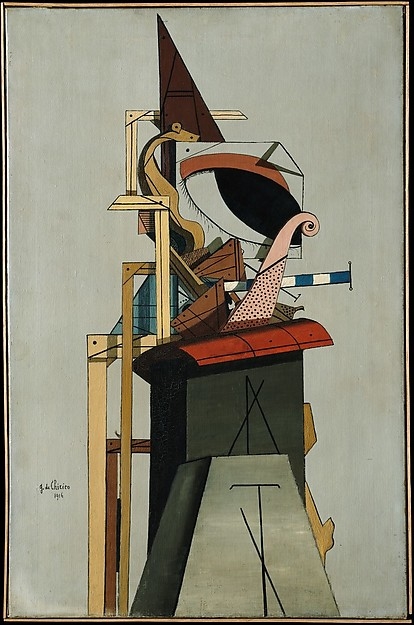

“De Chirico’s peculiar mindset and culture in those years, founded in a vein of art and thought that is definitely—broadly speaking—anti-impressionist: an idealistic critique on the categories of time and space” — Giorgio Castelfranco

This painting would become an inspiration for Sylvia Plath’s 1957 confessional poem (about her mother’s neglectfulness) “The Disquieting Muses.” Excerpt:

Day now, night now, at head, side, feet,

They stand their vigil in gowns of stone,

Faces blank as the day I was born,

Their shadows long in the setting sun

That never brightens or goes down.

And this is the kingdom you bore me to,

Mother, mother. But no frown of mine

Will betray the company I keep.

Created after Chirico returned to Italy from Paris to join the Italian Army in World War I. Chirico was moving away from the bright open scenes of his previous work. He was now focusing on more abstract combinations of objects and indoor settings, and seeking to paint the hidden meanings behind the surface of things.

Aleksei Kruchenykh’s Universal War opens with the bleak prophecy “Universal War will take place in 1985.” The book is an early attempt to link zaum poetry (often translated as “transrational” or “beyonsense” poetry) with zaum images. The book features Kruchenykh’s own collages, in an abstract style the artist referred to as “Non-Objective.” Germany is depicted as a belligerent spiky helmet with its shadow, a black panther, fighting Russia.

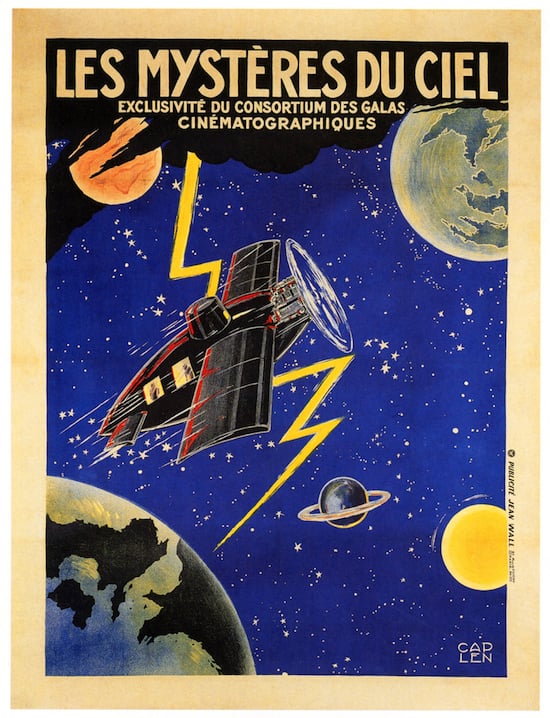

[The shooting down of a German dirigible over London]

September 3, 1916

H. Scott Orr

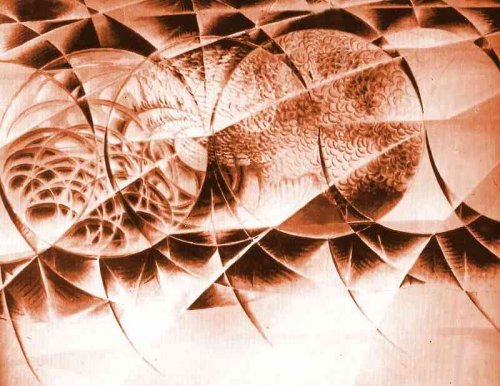

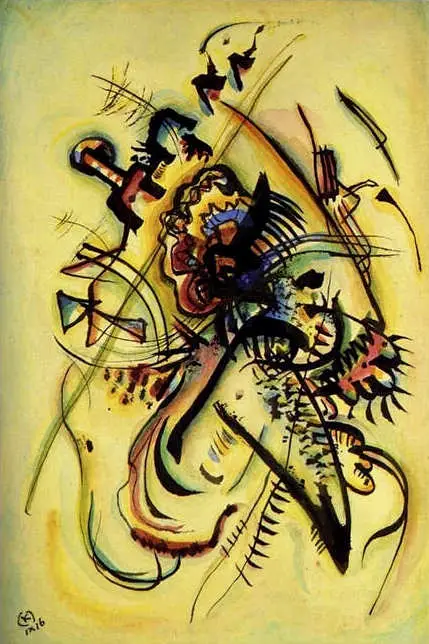

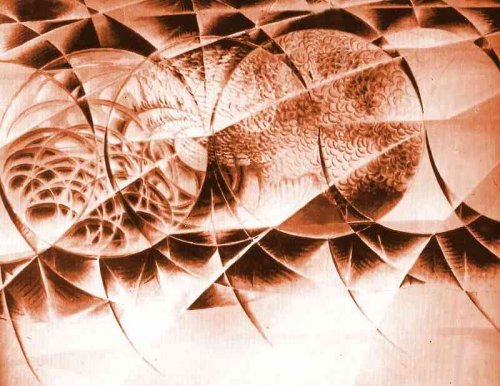

This watercolor work was created by Kandinsky in Moscow after a phone talk with a stranger whose name was Nina Andreevskaya. They were married one year later.

Precisionist artists reduced subjects to their essential geometric shapes.

Princess X depicts the Princess Marie Bonaparte, a great supporter of Freud and a psychoanalyst in her own right. The work was originally part of a “notorious scandal” when the Salon des Indépendants removed Princess X from display for its apparent obscene content.

The woman appears simultaneously clothed and unclothed in an interplay of transparencies, visual, tactile, and motor spaces, evoking a series of mind-associations between past present and future not atypical of Metzinger’s earlier works.

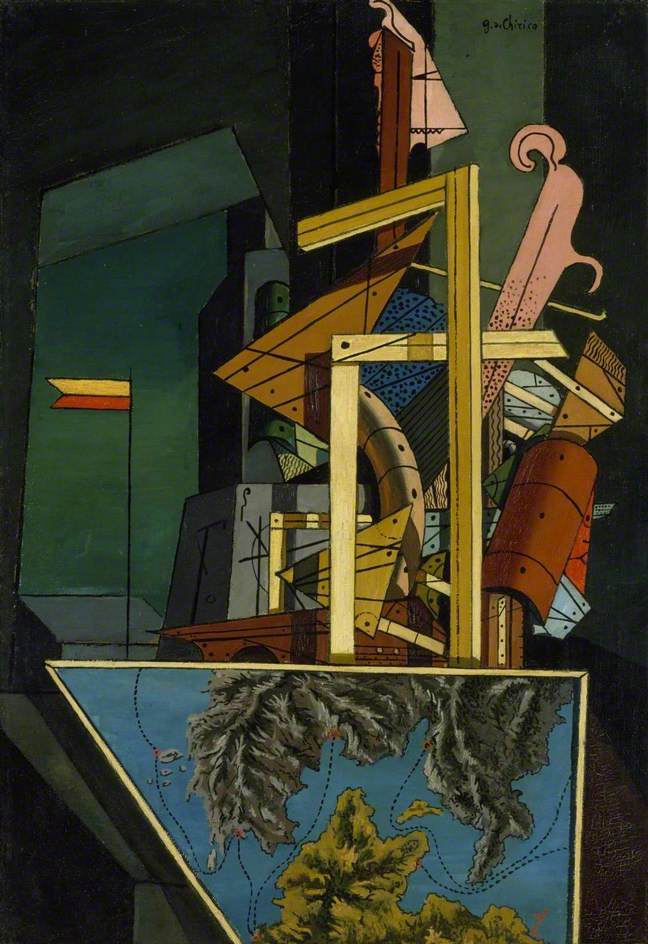

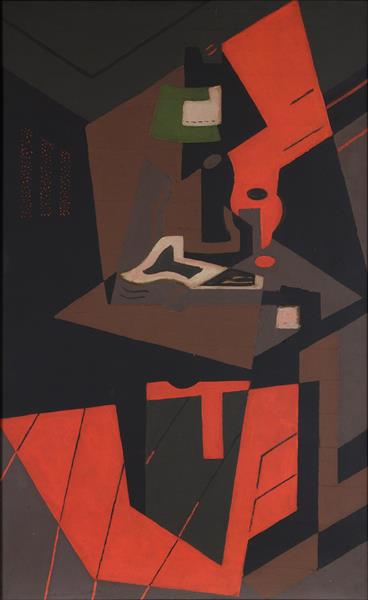

From The Met’s website: “This still life is exceptional in the oeuvre of this artist, whose acclaimed magical Italian cityscapes of 1911 to 1917 would influence the Surrealists a decade later. Painted wood elements, among them a pink-dotted French curve, blue-and-white meter stick, and right angles, are stacked pell-mell above what might be kilometer markers. Among these objects, an oversize eye, crudely drawn on a large piece of paper, surprises. De Chirico’s father was an engineer with a railroad company, and it has been suggested that this scaffold-like structure and eye might be an abstract portrait of him.”

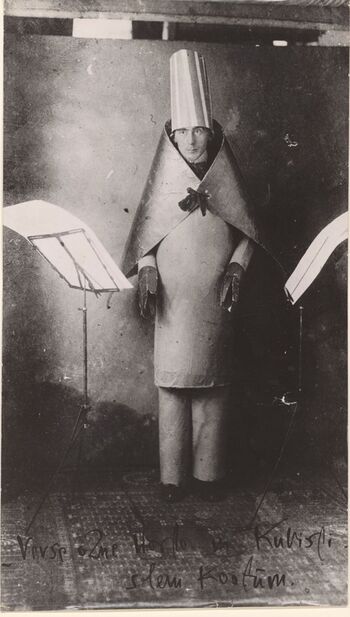

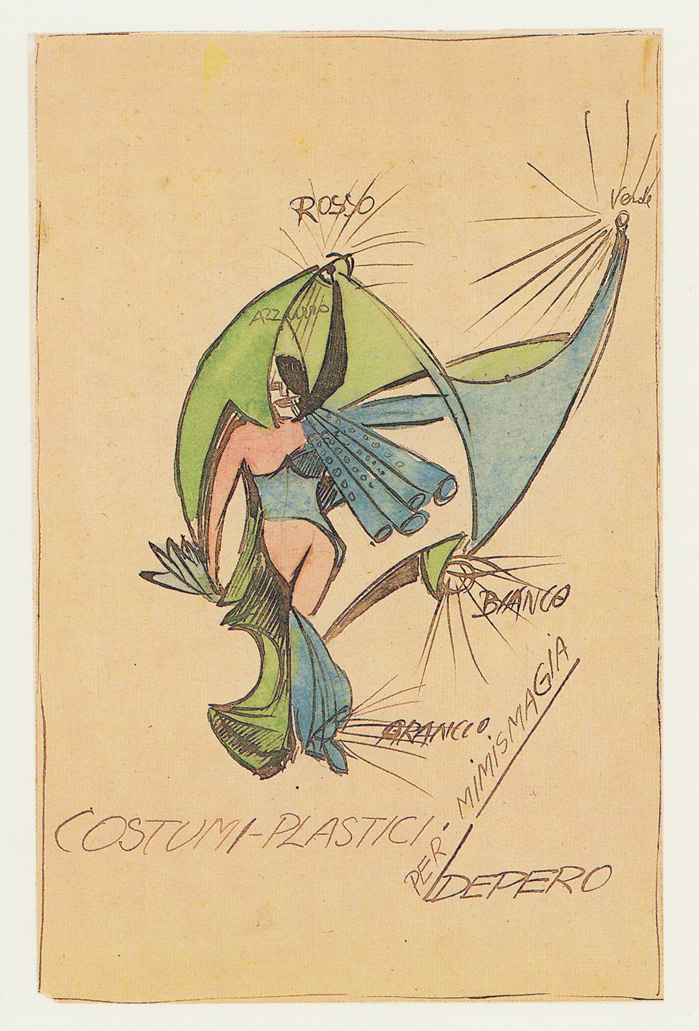

In 1916, Depero worked on a project with three dancer-robots, from which some costume designs survive. When they were first exhibited at the Galleria Sprovieri, the critic Mario Broglio described them as “externalized emotions presented in a mimic-acrobatic dance with sculpted costumes in transformation.” Colorful, transparent drapes were attached to wires and poles and furnished with a number of colored lights. In order to puzzle and surprise the audience, the actor could operate hidden devices that transformed the costumes and produced rhythmic noises. The idea for this “magic mime” was derived, it seems, from Loïe Fuller’s “radium” dances with illuminated stage costumes.

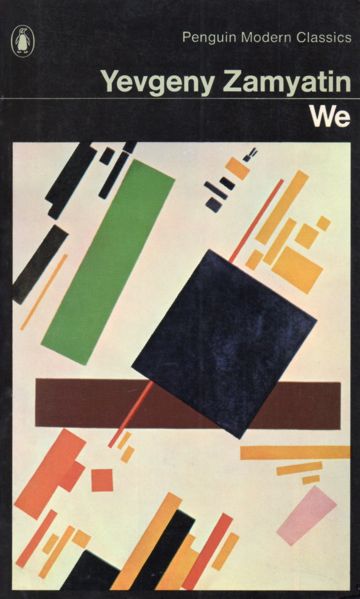

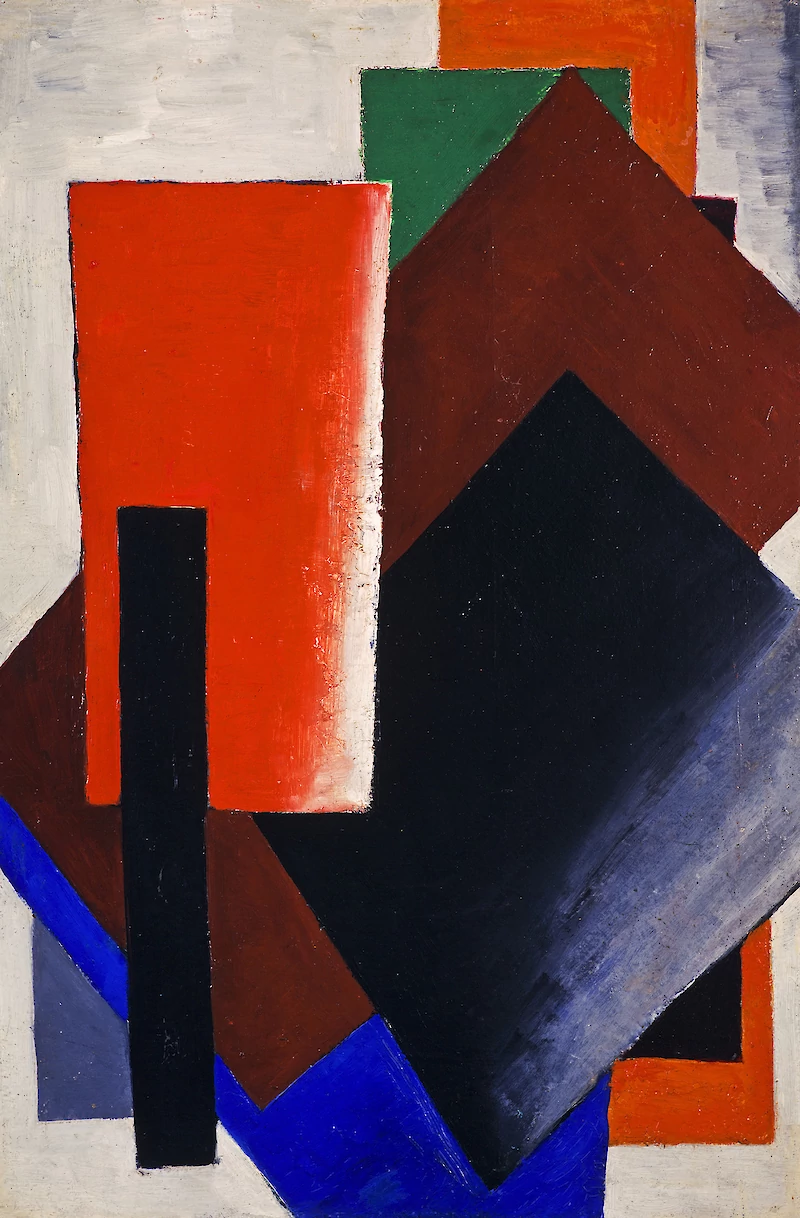

Malevich’s 1916 painting (above) was used as a cover illustration for a 1972 Penguin edition of Yevgeny Zamyatin’s 1921 proto-sf novel We. See below.

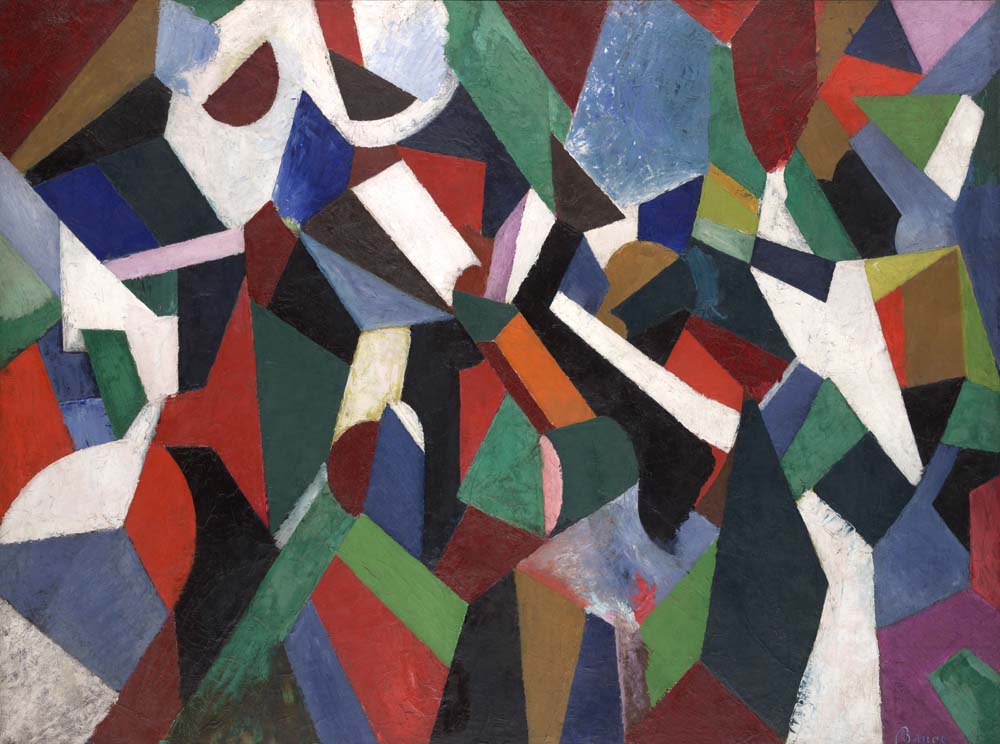

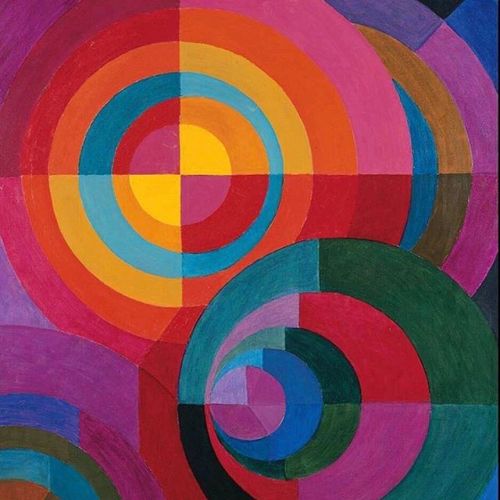

Bruce, one of the fIrst American abstract artists, here pairs bold, unmodulated color with an allover arrangement of flat forms. His abstract style grew out of his engagement with Robert and Sonia Delaunay’s theory of the simultaneous contrast of colors. He moved to Paris in 1904 and lived there for most of the rest of his life as an active participant in the city’s art world.

Blue is the name of four paintings that Georgia O’Keeffe made in 1916. It was one of the sets of watercolors that she made exploring a monochromatic palette with designs that were non-representational of specific objects

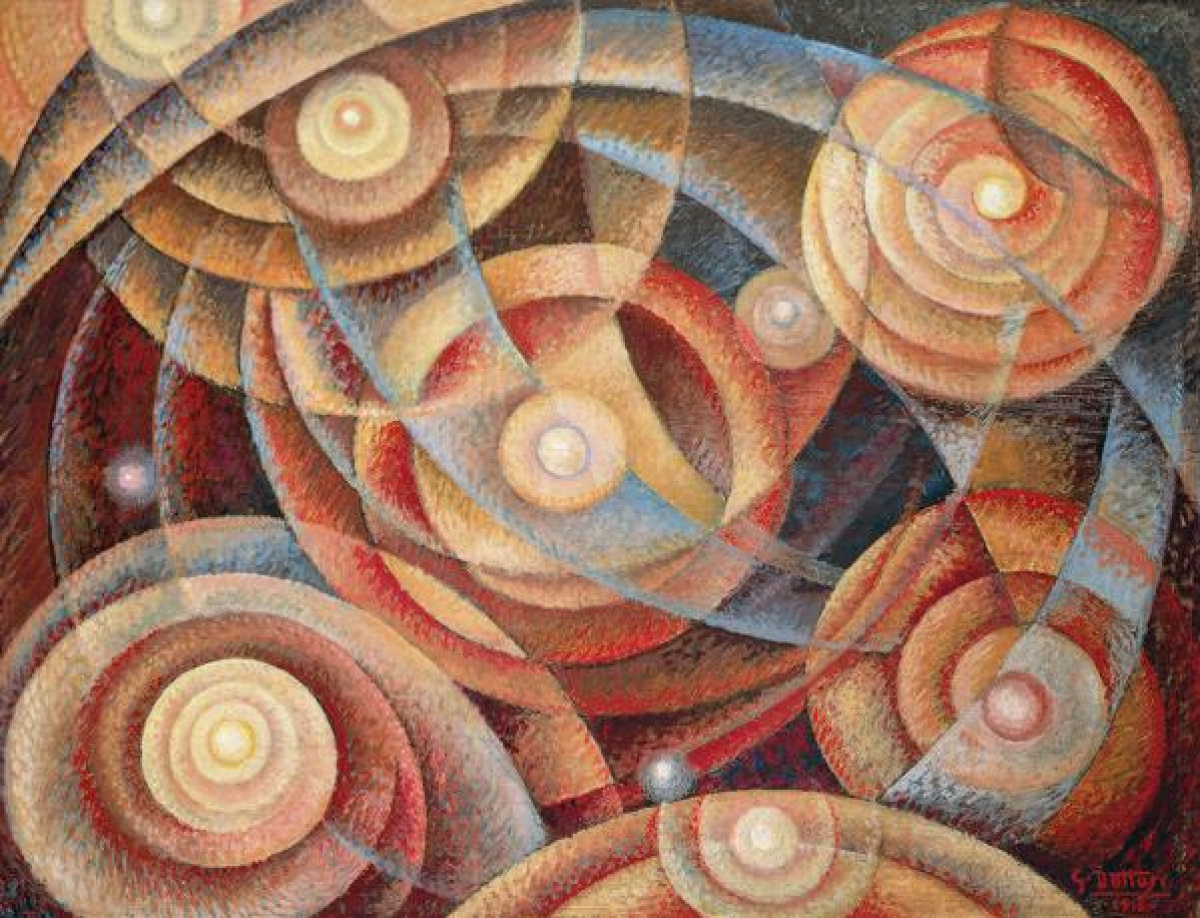

“Moscow represents duality, complexity and a high level of mobility, collision and confusion of separate elements of appearance… I consider this internal and external Moscow to be the starting point of my starving. Moscow is my pictorial tuning fork.’ — Kandinsky

MORE RADIUM AGE SCI FI ON HILOBROW: RADIUM AGE SERIES from THE MIT PRESS: In-depth info on each book in the series; a sneak peek at what’s coming in the months ahead; the secret identity of the series’ advisory panel; and more. | RADIUM AGE: TIMELINE: Notes on proto-sf publications and related events from 1900–1935. | RADIUM AGE POETRY: Proto-sf and science-related poetry from 1900–1935. | RADIUM AGE 100: A list (now somewhat outdated) of Josh’s 100 favorite proto-sf novels from the genre’s emergent Radium Age | SISTERS OF THE RADIUM AGE: A resource compiled by Lisa Yaszek.