RADIUM AGE ART (1913)

By:

May 14, 2024

A series of notes regarding proto sf-adjacent artwork created during the sf genre’s emergent Radium Age (1900–1935). Very much a work-in-progress. Curation and categorization by Josh Glenn, whose notes are rough-and-ready — and in some cases, no doubt, improperly attributed. Also see these series: RADIUM AGE TIMELINE and RADIUM AGE POETRY.

RADIUM AGE ART: 1900 | 1901 | 1902 | 1903 | 1904 | 1905 | 1906 | 1907 | 1908 | 1909 | 1910 | 1911 | 1912 | 1913 | 1914 | 1915 | 1916 | 1917 | 1918 | 1919 | 1920 | 1921 | 1922 | 1923 | 1924 | 1925 | 1926 | 1927 | 1928 | 1929 | 1930 | 1931 | 1932 | 1933 | 1934 | 1935 | THEMATIC INDEX.

The year 1913, in my periodization scheme, marks the end of the cultural decade known as the “Nineteen-Aughts.” Of course there are no hard stops and starts in culture, so it’s more accurate to describe 1913 (and 1914) as cusp years during which the Aughts end and the Nineteen-Teens begin.

“For me, the province of art and the province of nature … became more and more widely separated, until I was able to experience both as completely independent realms. This occurred to the full extent only this year.” — Kandinsky, in 1913

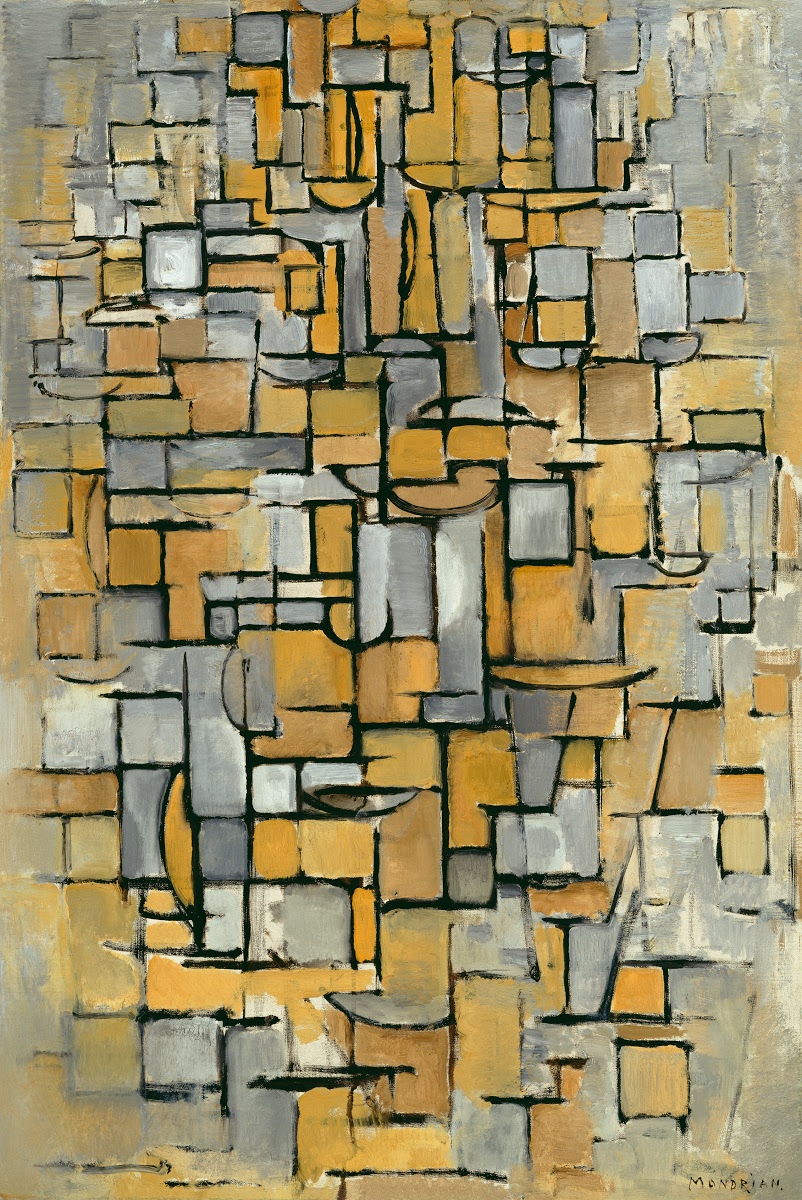

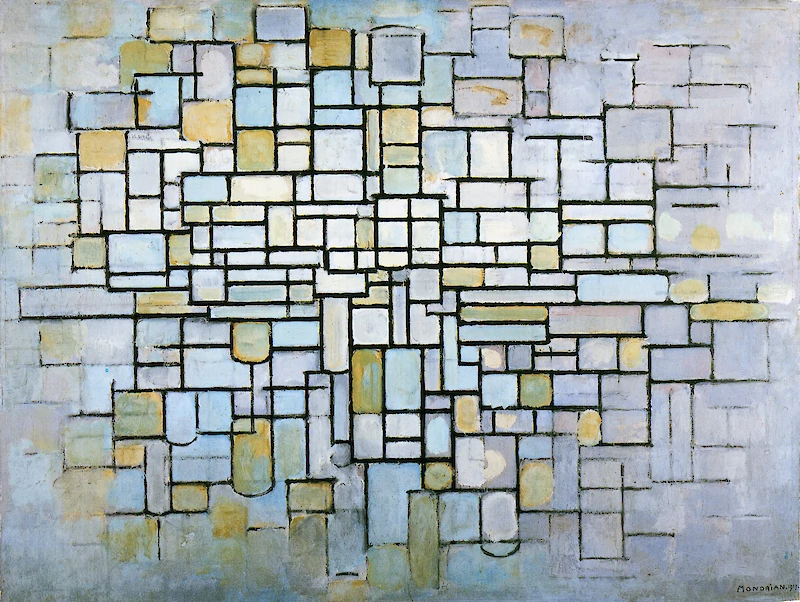

Mondrian at this time is eliminating curves and diagonals from his paintings. His decision seems to be motivated by a mystical belief that the vertical and the horizontal represent the two foundational dimensions of existence: the first signifying consciousness, masculinity and the sky, the second unconsciousness, femininity and the earth. In contrast to these eternal (binary oppositions) principles, curves and diagonals are mere accidents, too ephemeral for inclusion in high art.

Shattuck claims the climax of the Banquet Years (heady era between Symbolism and High Modernism) came in 1913 — Vorticism breaks out in London, the Armory Show scandal in New York, Apollinaire’s Alcoöls, etc.

Man Ray cofounds an artist’s colony — Grantwood — in New Jersey. It becomes became the artistic center for a collective known as the “Others.” In 1915, Alfred Kreymborg launched Others: A Magazine of the New Verse with Skipwith Cannell, Wallace Stevens, and William Carlos Williams. See PDFs here.

1913: Apollinaire’s Les Peintres cubistes. Méditations esthétiques. Written between 1905–1912, published in 1913. The third chapter (adapted from a 1912 article, itself adapted from a 1911 lecture) is the best-known early critical statement linking Cubism to notions of the Fourth Dimension.

The 1913 Armory Show was the first large exhibition of modern art in America.

In Munich, Hugo Ball charged with obscenity for his violent poem “Der Henker”; he and avant-garde theatrical performer Emmy Hennings are drawn into expressionist circles; Ball and Kandinsky plan an experimental, multimedia theater in Munich — at one planning meeting for which Ball befriends Richard Huelsenbeck.

By 1913 Duchamp leaves behind the organic world of x rays for the realms of geometry, science, and the machine.

Van Doesburg’s style of painting changed in 1913 after he read Kandinsky’s autobiographical Rückblicke — which led him to realize that there is a more spiritual level in painting that originates from the mind rather than from everyday life; and that abstraction is the only logical outcome of this.

Kandinsky producing his first unequivocally non-representational artwork, including Untitled (Study for Composition VII, first abstraction), around this time.

Malevich — under the influence of P D. Ouspensky, as well as the poet Velimir Khlebnikov — founds Suprematism, an art movement focused on the fundamentals of geometry (circles, squares, rectangles), painted in a limited range of colors. The movement’s moniker refers to an abstract art based upon “the supremacy of pure artistic feeling” rather than on visual depiction of objects.

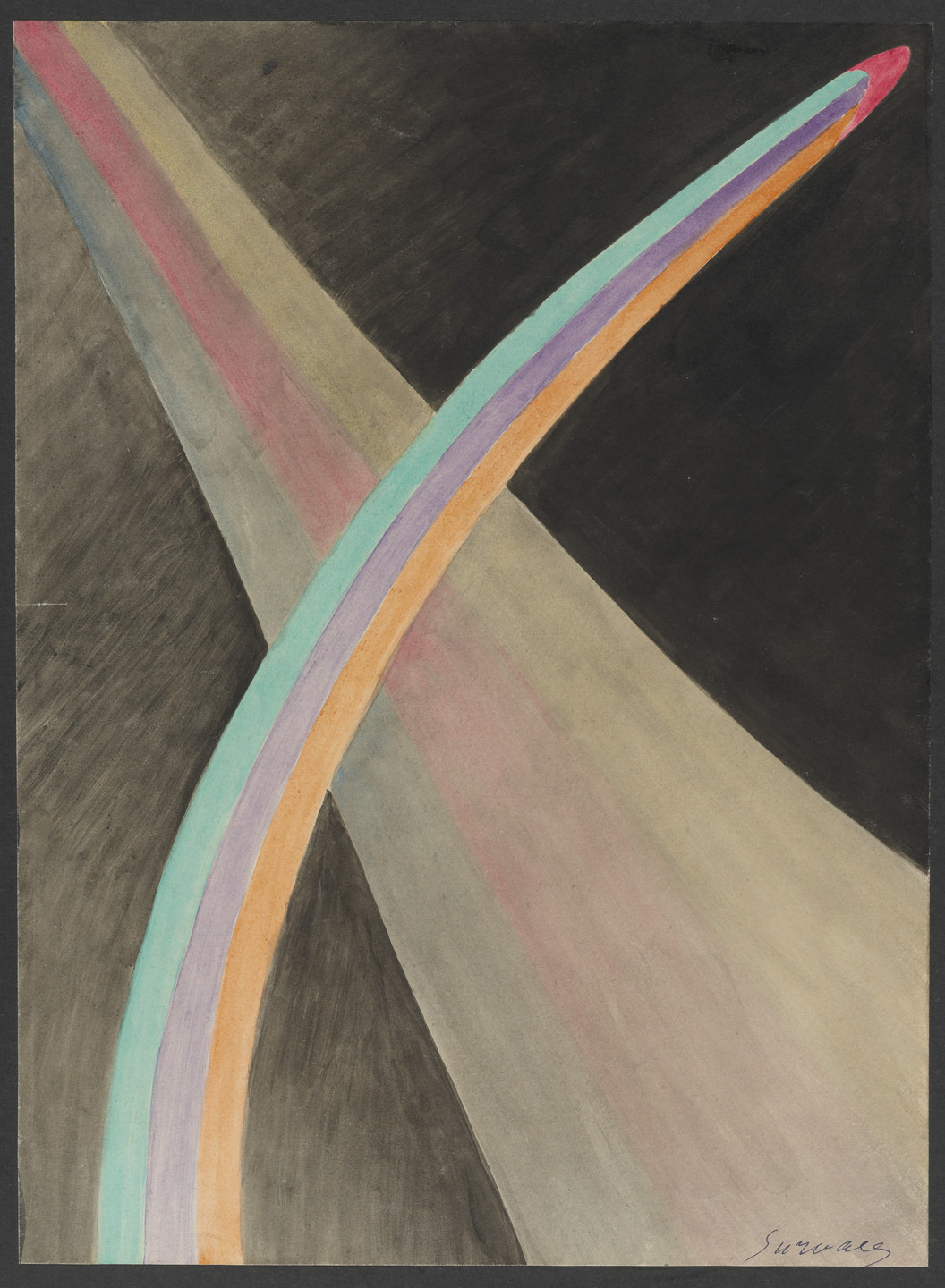

Rayism named in 1913, by the Russian painter Larionov, who touts his new style as a “synthesis” of Cubism, Futurism, and Orphism.

Picabia stated while in New York, in 1913, that “art is a successful attempt to exteriorize the thought or the inner feeling by projecting on the canvas subjective, emotional, mental states.”

An April 1913 article by the American critic Christian Brinton, titled “Evolution Not Revolution in Art,” attempts to explain European modern art to an American audience. Using the term “Expressionistic” to signify art since Impressionism, Brinton gives considerable attention to both Picasso and Picabia and concludes with the following argument:

There is no phase of activity or facet of nature which should be forbidden the creative artist. The X-ray may quite as legitimately claim his attention as the rainbow, and if he so desire he is equally entitled to renounce the static and devote his energies to the kinetoscopic. If the discoveries of Chevruel [sic] and Rood in the realm of optics proved of substantial assistance to the Impressionists, there is scant reason why those of von [sic] Röntgen or Edison along other lines should be ignored by Expressionist and Futurist […] The point is that they will add nothing [to the accumulated treasury of the ages] unless they keep alive that primal wonder and curiosity concerning the universe, both visible and invisible, which was characteristic of the caveman, and which has proved the mainstay of art throughout successivecenturies.”

[Quoted in Linda Dalrymple Henderson’s “X Rays and the Quest for Invisible Reality in the Art of Kupka, Duchamp, and the Cubists” (Art Journal, 1988). Henderson’s thesis: “We must rediscover the variety of images, concepts, and individuals associated with x rays and radioactivity in order to recognize their reflections in French art and theory. Similarly, only in returning to those sources can one fathom the enormous impact of these invisible rays which clearly established the inadequacy of human sense perception and raised fundamental questions about the nature of matter itself.”]

Cubo-Futurism or Kubo-Futurizm was an art movement, developed within Russian Futurism, that arose in the Russian Empire, c. 1913, defined by its amalgamation of the artistic elements found in Italian Futurism and French Analytical Cubism.

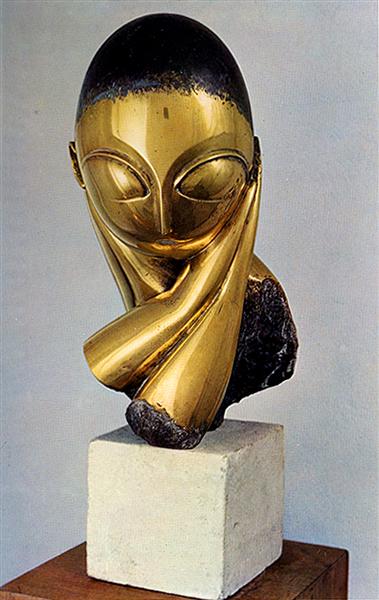

Note that Boccioni’s Futurist sculpture Unique Forms of Continuity in Space (1913) would be mentioned in Edward Shanks’s apocalyptic proto-sf novel The People of the Ruins (1919).

Proust’s first installment of A la recherche du temps perdu (which mentions the concept of “un espace à quatre dimensions”)

Husserl’s Phenomenology

In 1913 Bohr proposes the now familiar model of the atom as a miniature solar system, with the positively charged nucleus as the sun and the electrons as planets circling in intersecting orbits around it. Bohr’s discovery seemed to confirm the occult belief in a correspondence between the “above” and the “below.”

US architect and theosophist Claude Bragdon’s A Primer of Higher Space (1913) — another popular explication of theories of the fourth dimension, relying heavily on Hinton and Zöllner — “4-dimensional vision” seems to be essentially X-ray vision. Like Leadbeater’s Clairvoyance (1899), Bragdon connects x-ray-like “astral vision” to four-dimensional sight.

Stories of space travel and colonies on distant planets were popular in Russia in the years leading up the Revolution. By writing about space colonies. author could describe utopian socities without directly challenging the Czarist government. Cf. Alexander Bogdanov’s Red Star (1908), set in a Martian worker’s paradise.

Victory over the Sun is a Russian Futurist opera that premiered in 1913 in Saint Petersburg. It’s set in the distant future, on a distant planet. The plot concerns a group of protagonists who want to destroy reason, by disposing of time and capturing the sun.

The libretto was contributed by the poet Aleksei Kruchonykh [Aleksei Kruchenykh; see this poem], the music was written by the painter and composer Mikhail Matyushin [Matiushin], the prologue was added by the poet Velimir [Viktor] Khlebnikov [see this poem], and the stage designer was the painter Kazimir Malevich (who created costumes from simple materials and took advantage of geometric shapes). The stage curtain was a black square.

One of Malevich’s sketches for the stage curtain (titled “Interplanetary Travel”) includes three conical spaceships flying in different directions. I have only seen this sketch reproduced in Abstract Art: A Global History. The sketch would become Malevich’s 1915 abstract painting Suprematist Painting (with black Trapezium and Red Square), minus the spacecraft.

All of which helped Malevich conceive of his art movement Suprematism, which he founded the same year.

Performed in December of 1913 to the St. Petersburg public, this Cubo-Futurist opera was a shocking spectacle for its audience. Its storyline follows the action of the people of the future as they capture the sun, which represents the decadent past. They tear it from the sky and lock it in a concrete box before giving it a funeral, conquering the natural world with technology. The script, written primarily by Alexei Kruchenykh, relied heavily on the use of zaum, a nonsensical language frequently used by the Russian Futurists as a mode of expression that transcended the restrictions of normal speech. The costumes, designed by Kazimir Malevich, transformed actors into stiff, brightly-colored geometric figures against black and white backdrops, some of which bordered on the abstract in their simplicity. The hectic music, written by Mikhail Matiushin, was played on an out-of-tune piano and sung by amateurs.

See: RADIUM AGE: 1913

Speaking of catastrophe, J.D. Beresford’s A World of Women (reissued by the MIT Press’s RADIUM AGE series) appears in 1913. A plague kills almost every male in England.

Also: H.G. Wells’s The Poison Belt (reissued by the MIT Press’s RADIUM AGE series) appears in 1913.

Meidner wrote in his journal in 1913: “The giggles of the city ignite against my skin. I hear eruptions at the base of my skull. The houses near. Their catastrophes explode from their windows, stairways silently collapse. People laugh beneath the ruins.”

From the LACMA website: “Painted a year before the first shot would be fired in World War I, Apocalyptic Landscape is an uncanny premonition of the cataclysm the war would bring. Under a turbulent sky, a city street appears to fracture as the earth quakes and figures run chaotically in the foreground. Though the scene owes much to the dynamism and energetic brushwork characteristic of Italian Futurism that Meidner saw at a Berlin gallery a few months before this painting was completed, it is a decidedly Expressionist work, linking an emotional state with the scene depicted. One of approximately fifteen apocalyptic landscapes Meidner would paint between 1912 and 1916….”

A journey to nowhere, observed by no one. Reminds me of a poem I read about neutrinos.

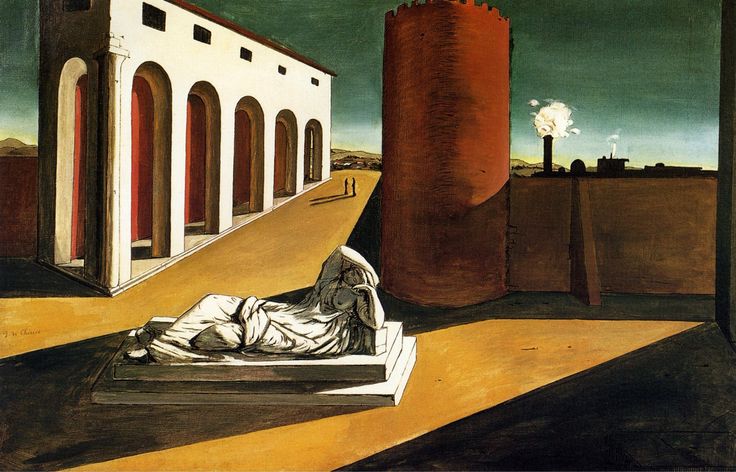

Pepe Karmel notes” “Emotionally, the architectural imagery of abstract art is haunted by de Chirico’s vision of the modern city as an empty stage set, where the drama of humanism has come to an end but nothing else has arrived to take its place.”

Kupka, a lifelong spiritualist and a devotee of Theosophy, here gives us a diagram of the heavens and a nonrepresentational, antidirectional image referring to infinity. This painting was a crucial first step in his journey to abstraction. PS: It’s been said this painting may have been influenced by A.P. Sinnett’s diagram of the “planetary chain” in the 1883 book Esoteric Buddhism.

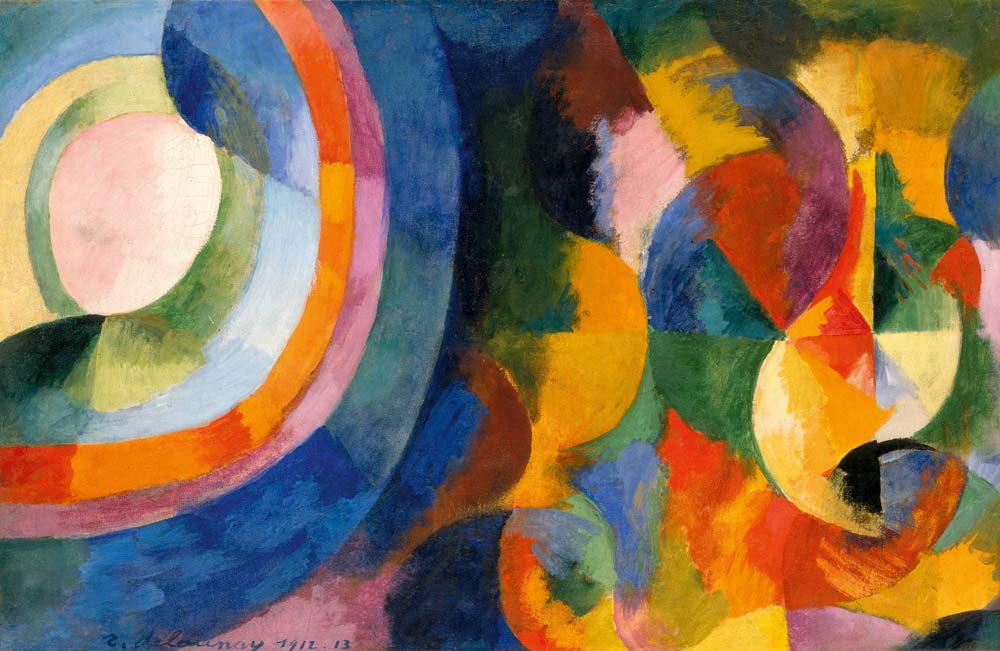

A deep sense of spirituality runs through Delaunay’s work. In 1913 he adopted the sun and moon as abstract symbols of enlightenment, first opposed and then merging into a single, multi-colored disk. He included the primary colors, together with their complements. Pepe Karmel suggests that his goal seems to have been “spiritual seduction, leading the viewer through color towards divine light.”

From a New York Times review of a 2024 Orphism show at the Guggenheim:

As you walk up the ramp of the Guggenheim, it is fascinating to realize the degree to which Delaunay’s theories — as encapsulated in the form of the disk or flat circle — spread through the studios of Europe. He reinvented disks as an emblem of reeling modernity. Other artists adopted the form while extracting a range of meanings from it; in the course of the show, disks variously evoke giant eyeballs, the overlapping gears of a Swiss watch or the eternal orbit of planets.

From the book MoMA Highlights: 350 Works from the Museum of Modern Art New York (second edition, 2004):

“Delauney was fascinated by how the interaction of colors produces sensations of depth and movement, without reference to the natural world. In Simultaneous Contrasts that movement is the rhythm of the cosmos, for the painting’s circular frame is a sign for the universe, and its flux of reds and oranges, greens and blues, is attuned to the sun and the moon, the rotation of day and night. But the star and planet, refracted by light, go undescribed in any literal way. “The breaking up of form by light creates colored planes,” Delauney said. “These colored planes are the structure of the picture, and nature is no longer a subject for description but a pretext.” Indeed, he had decided to abandon “images or reality that come to corrupt the order of color.”

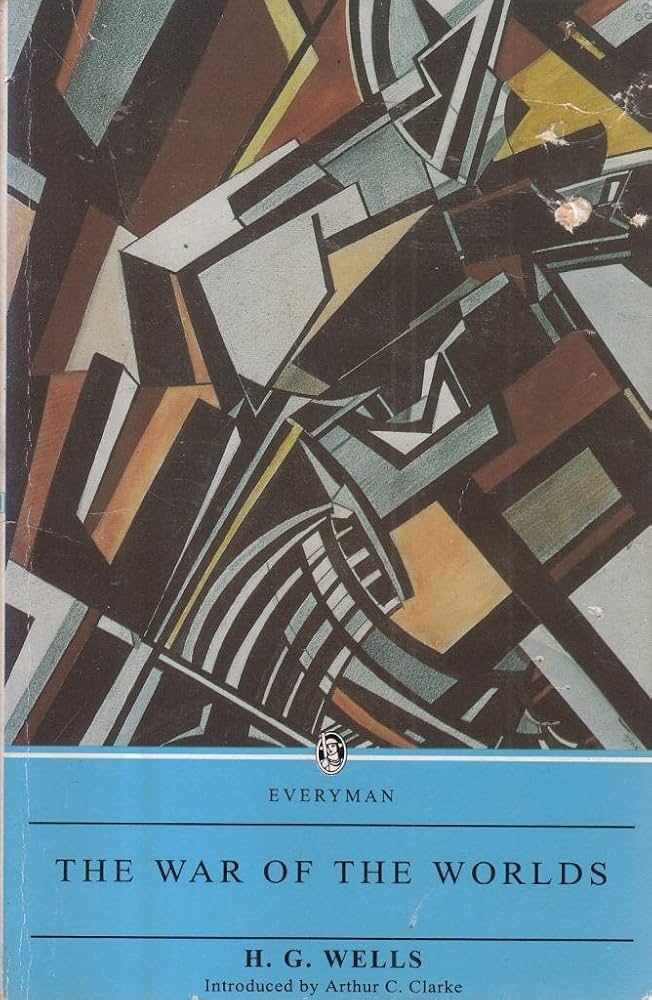

See below for an example of this artwork used as an sf book cover illustration.

From the website Art History Project: “Elsa Endell, kaleidoscopic performance artist and poet is on her way to New York’s city hall for her third marriage, this time to a German Baron named Leopold von Freytag-Loringhoven. En route, Elsa spots a rusted iron ring. To Elsa this street trash was a totem of her marriage to be, and in an act marking a new era in the definition of art — Elsa called this found object an artwork.”

Albert Gleizes, Jean Metzinger, Robert Delaunay, Henri le Fauconnier, Fernand Léger and Marie Laurencin’s 1911 Salon des Indépendants show brought the so-called Section d’Or collective to prominence. The Salon de la Section d’Or, held October 1912, was even more notable… and brought Alexander Archipenko, Joseph Csaky, Roger de La Fresnaye, Juan Gris, and Jean Marchand into their circle. František Kupka and Francis Picabia were in the mix, too, along with the Duchamp brothers, who exhibited under the names of Jacques Villon, Marcel Duchamp and Raymond Duchamp-Villon.

Also see: Hélène Oettingen, Alexander Archipenko, Constantin Brâncuși, Joseph Csaky, Alexandra Exter (or Ekster), Marthe Donas, Pierre Dumont, Natalia Goncharova, Jean Lambert-Rucki, André Lhote, Louis Marcoussis, André Mare, Irène Reno, Georges Ribemont-Dessaignes, Jeanne Rij-Rousseau, André Dunoyer de Segonzac, Tobeen.

De La Fresnaye presents a geometric world where clouds are spheres and all objects are formed by elementary, Euclidean solids. De La Fresnaye’s mathematical influence can be traced in his 1912–1914 participation in the “Section d’ Or” or “Puteaux group”, a collective of artists that displayed strong belief in the significance of mathematical proportions and especially the golden ratio.

Interesting website about mathematics and culture.

The generic title of Mondrian’s painting signifies that he wanted it to be perceived as a purely abstract composition. However the converging diagonals of the bottom third point back to his Composition no. XI (1912), which was itself an abstract version of an earlier painting, Study for Woman (c. 1912). The shallow arcs attached to vertical or horizontal lines, which indicate the spots where the lines of the abstract grid coincide with elements of the now-invisible woman, are device borrowed from Mondrian’s heroes Picasso and Braque.

An early association with Picasso and Braque led Gris into Cubism. In 1921 Gris will write: “I work with the elements of the intellect, with the imagination. I try to make concrete that which is abstract…”

A founding member with Duchamp of the Section d’Or, Picabia painted Udnie as he was emerging from a short-lived Cubist period. Choreographic in inspiration, it is a remembrance of a ballerina the artist met while crossing the Atlantic in 1913. Also known as “American Girl” or “The Dance.” This painting is influenced by the dynamism of futurism and the “mechanism” of Marcel Duchamp’s works. The abstract forms, in his centrifugal movement, and the metallic colour reflections recall the world of machines.

The painting’s title is possibly an anagram of the name of musicologist Jean d’Udine, who had a theory of sensory correspondences.

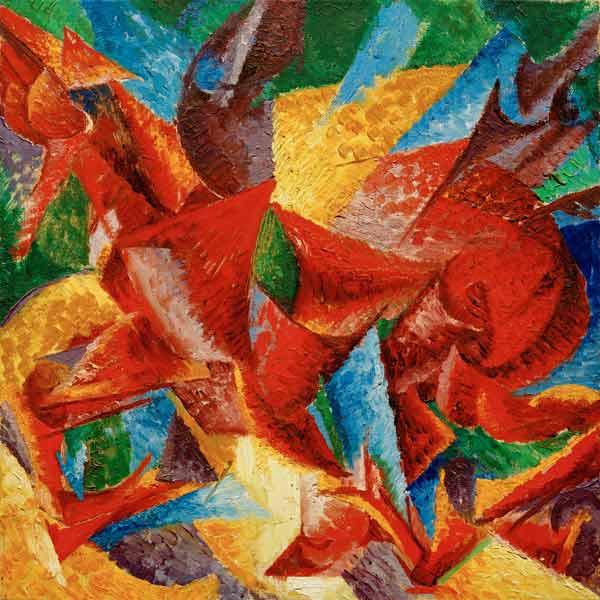

Boccioni’s goal for the work was to depict a “synthetic continuity” of motion instead of an “analytical discontinuity” that he saw in artists like František Kupka and Marcel Duchamp. This sculpture integrates trajectories of speed and force into the representation of a striding figure. A figure in constant motion, immersed in space, engaged with the forces acting upon it.

Boccioni’s work was in plaster, and was never cast into bronze in his lifetime. Two bronze casts were made in 1931, one of which is displayed at MoMA.

See 1912 installment for a brief discussion of Robert and Sonia Delaunays’ development of “Simultanism” (somewhat confusingly titled “Orphism” or “Orphic Cubism” by Apollinaire). Their idea, based on color theory, held that a viewer’s simultaneous perception of contrasting hues generates rhythm, emotion, movement, and depth. In adopting the term Simultanism to describe their paintings, the Delaunays combined reference to a famous text on color theory with recent philosophical and scientific explorations of perception and memory. The art they produced reflected this combination in its synthesis of formal concerns and modern subject matter.

Inspired by Cendrars’s recitations of his poetry, Delaunay-Terk proposed that they collaborate on a “simultaneous book,” with his text set in contrasting colors parallel to her designs. Across 446 lines, Cendrars’s freewheeling travel poem fuses reality, memory, and imagination in a breathless flow of spontaneous impressions. Narrated by a man named Blaise, the poem takes place on a train trip from Russia to China, though it concludes in Paris (note the little red representation of the Eiffel Tower). Colors and words drift in a nonlinear fashion similar to a stream of consciousness, a state in which time and location are irrelevant.

From the book MoMA Highlights: 350 Works from the Museum of Modern Art New York (second edition, 2004): “Delauney-Turk’s hues and Cendrars’s prose interact on a simultaneous journey, producing synchronized rhythms of art and poetry.”

“Blaise Cendrars” is the pseudonym of Swiss-born editor, controversialist, adventurer (though his memoirs contain a great deal of fiction), poet, film maker and author Frédéric-Louis Sauser (1887-1961). He was in active service during World War One, losing an arm in combat. His career as experimenter, agitator, constantly restless plunger into numerous genres (which he mixed), began before the War. Of proto-sf interest are: Le fin du monde filmée par l’Ange Notre-Dame, Roman (1919 chap; trans Esther Allen as “The End of the World Filmed by the Angel of Notre Dame”), a script for an imaginary film in which God, having filmed World War One, which satiates him only briefly, now plans to create the end of the world through special effects; Kodak (Documentaire) (1924, trans. Ron Padgett as “Kodak: Documentary”), a kind of prose-poem collaged from the text of the French proto-sf novel Le Mystérieux Docteur Cornelius by Gustave Le Rouge; L’Eubage, aux antipodes de l’unité (1926; trans Esther Allen as “The Eubage; Or, at the Antipodes of Unity”), which combines interstellar space opera and deadpan philosophical musings, anticipatory of the work of Lem; and Moravagine (1926; trans Alan Brown 1969), in which a mad scientist psychologist lets loose the eponymous serial-killer patient; they traverse the globe causing havoc, achieving dubious godhood up the Amazon, until the start of World War One.

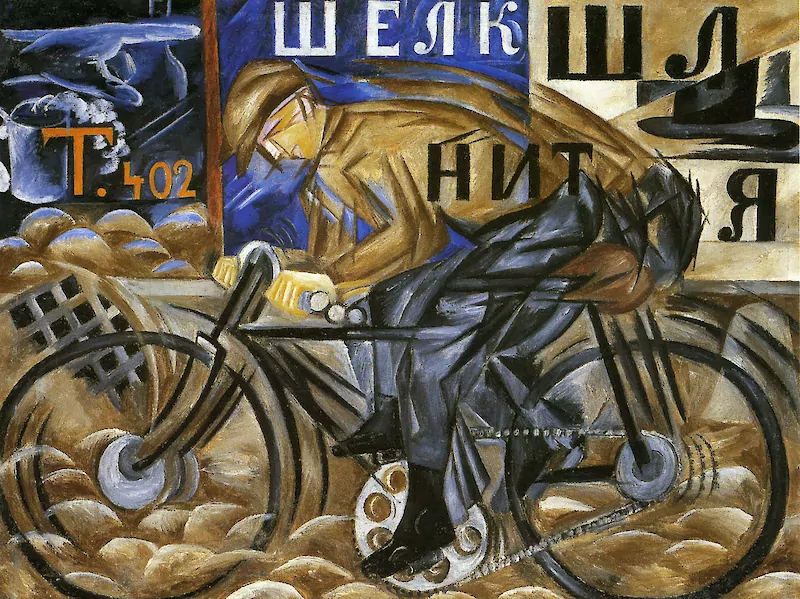

From 1913 to 1914, Cubo-Futurist ideas appeared in Rozanova’s work, but she appears to have been especially inspired by Futurism. Of all the Russian Cubo-Futurists, Rozanova’s work most closely upholds the ideals of Italian Futurism.

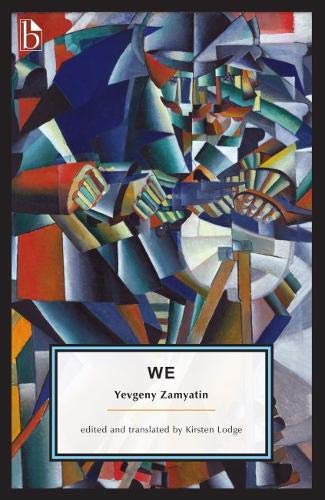

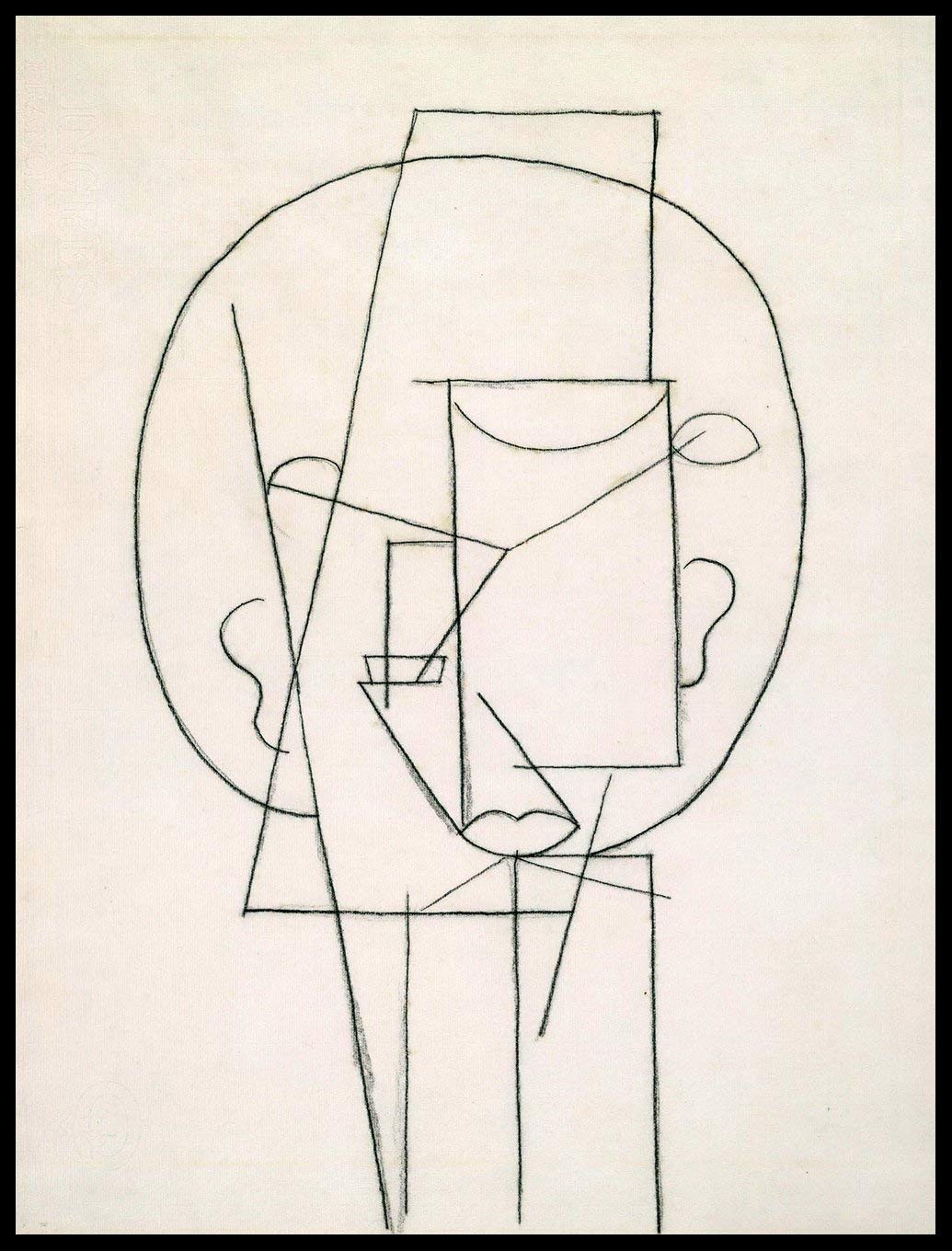

A landmark in the history of the Russian avant-garde. The linear organization of Malevich’s “Perfected Portrait of Ivan Kliun, Constructor” (1913) is modeled on Picasso’s portrait of Apollinaire (which had been reproduced in Apollinaire’s Alcools in 1913). The deconstructed elements of Kliun’s face are arranged in a grid. However it is more colorful than French cubist paintings — likely because Malevich only saw such work in b/w reproductions. Also while Picasso and Braque give us flat planes, Malevich’s metallic shading require us to read the various elements here as cones and cylinders — more like Léger’s “tubism.”

Malevich’s painting was used to illustrate the cover of a 2020 edition of Yevgeny Zamyatin’s proto-sf novel We. See below.

From The Met’s website: “In March 1912 Boccioni wrote, ‘These days I am obsessed by sculpture! I believe I have glimpsed a complete renovation of that mummified art.’ A month later he published the ‘Technical Manifesto of Futurist Sculpture,’ and by June 1913 he had produced eleven sculptures, including Development of a Bottle in Space. Rather than delineating the contours of his subject, a bottle, Boccioni integrated the object’s internal and external spatial planes, which appear to unfold and spiral into surrounding space.”

Boccioni first provided a sketch of Development of a Bottle in Space in his manifesto, as an example of a work that deconstructs the three-dimensional space in and around itself. A year later he would produce the work’s recognizable form as a bronze sculpture. Boccioni proclaimed his intention to “open the figure like a window and include it in the milieu in which it lives.”

Rosalind Krauss: “The sculpture dramatizes a conflict between the poverty of information contained in the single view of the object and the totality of the vision that is basic to any serious claim to know it.”

The painting’s fragmentation and reassembly of an aerodynamic car into triangles suggest Cubist influences. Horizontally stacked red arrows indicate the direction of the car’s motion. The compression of the arrows on the left also suggests that the car is moving at an extremely high speed.

One of only two female members of the Vorticists’ movement (c. 1914), Saunders’s work was later sidelined. (The exhibit Women in Abstraction, at the Pompidou and Guggenheim Bilbao in 2021, helped correct for this.) This painting predates the Vorticism Manifesto, and reveals that the artist was already interested in depicting technology. However, whereas Wyndham Lewis’s art was almost entirely about machinery, Saunders’s artwork feels more emotional and subjective.

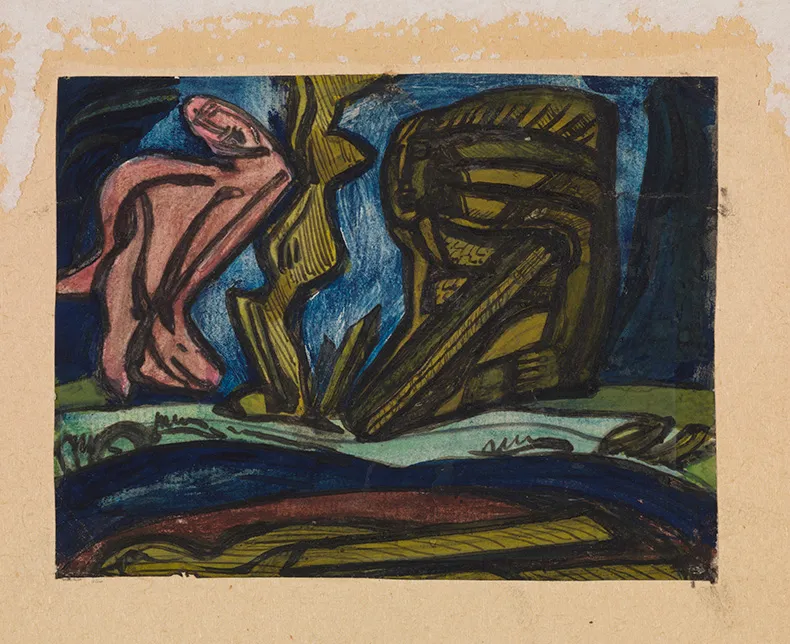

The painting is called either “Rock Drill” or “Driller”; sometimes the amorphous pink figure on the left is interpreted as a female. Some critics see here a confrontation between a soft form (a human) and an aggressive machine that easily destroys rocks.

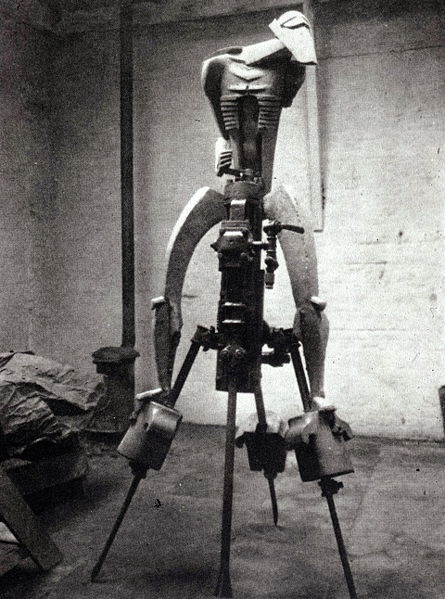

See Jacob Epstein’s 1913 sculpture “The Rock Drill.”

Saunders’s output during this Vorticist period was said to be substantial, though a 1940 German bomb destroyed most of it.

There are several versions of this sculpture. In representing its subject through highly stylized and simplified forms, the work departed significantly from conventional portraiture.

Epstein, who in 1910 designed the monument for Oscar Wilde’s tomb in the Père Lachaise Cemetery, intended to have this sculpture cast in steel — but he couldn’t afford to. He made the upper figure in plaster instead. The menacing body mounted on the drill appeared to be assembled from machine parts, including a head on a shaft with the only organic feature the foetus within the creature’s open rib-cage. The critic’s response was almost universally hostile and abusive.

The combination of an industrial rock drill and the carved plaster figure makes the artwork an example of a “Readymade” created at the same time as Marcel Duchamp’s “Bicycle Wheel” (1913).

Originally a positive statement, “Rock Drill” was intended as a celebration of modern machinery and masculine virility. In May 1916, Epstein, apparently mortified at the continuing slaughter of the war, made the decision to break up the sculpture. He removed the drill entirely and reduced the upper figure to a legless one-armed torso, which he had cast in gunmetal. In 1940, however, recalling the horrors of the 1914–18 war in the context of the Second World War, Epstein reinterpreted the sculpture:

My ardour for machinery (short-lived) expended itself upon the purchase of an actual drill, second-hand, and upon it I made and mounted a machine-like robot, visored, menacing, and carrying within itself its progeny, protectively ensconced. Here is the armed sinister figure of to-day and to-morrow. No humanity, only the terrible Frankenstein’s monster we have made ourselves into.

Also see Jessica Dismorr’s 1915 poem “Monologue.”

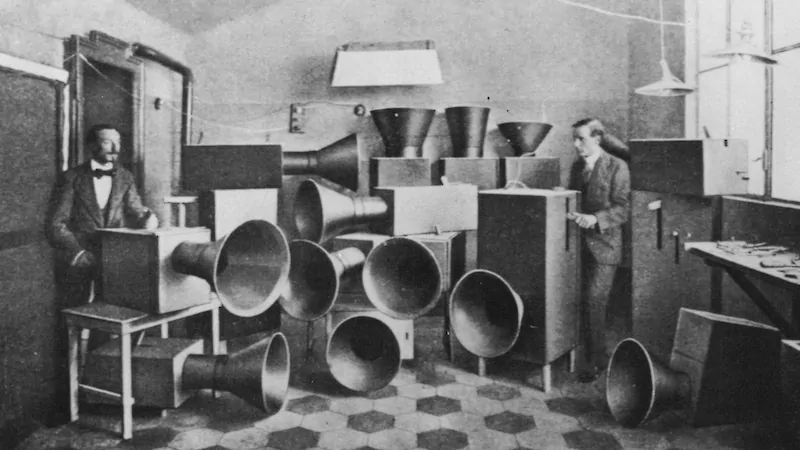

Luigi Russolo had a vision for a new kind of music, “where melody and harmony were replaced with scrapes, wails and thundering screams. It was a new, Futurist music, the audible expression of the industrialization and political dissent that rocked Italy after the turn of the century.” He built the Intonarumori, over twenty years — 27 new instruments, a series of acoustic boxes containing mechanics for creating rattles, scratches and roars.

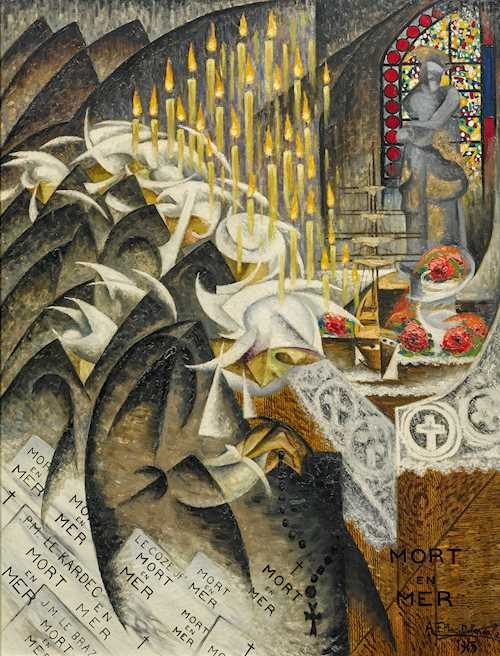

See below for the use of this artwork as the cover illustration for an sf novel.

Macke belongs in the circle of Kandinsky and Marc, whom he followed into the Blaue Reiter group. His declared aim was “to dissolve the spatial energies of color.” He shared with Marc and Klee a feeling of identification with life-forces outside the Self, forms that are the expression of mysterious powers. “The senses are the bridge from the incomprehensible to the comprehensible.”

Delaunay’s swirling discs form a prism through which viewers can recognize three symbols of late 19th– and early 20th–century modernity — the Eiffel Tower, a biplane, a Ferris wheel. This “Orphic” painting is notable for its energetic lines, shapes, and the warm, bright colors that radiate from a kaleidoscopic sun.

From the Guggenheim website: “After Marc Chagall moved to Paris from Russia in 1910, his paintings quickly came to reflect the latest avant-garde styles. In Paris Through the Window, Chagall’s debt to the Orphic Cubism of his colleague Robert Delaunay is clear in the semitransparent overlapping planes of vivid color in the sky above the city. The Eiffel Tower, which appears in the cityscape, was also a frequent subject in Delaunay’s work. For both artists it served as a metaphor for Paris and perhaps modernity itself. Chagall’s parachutist might also refer to contemporary experience, since the first successful jump occurred in 1912.”

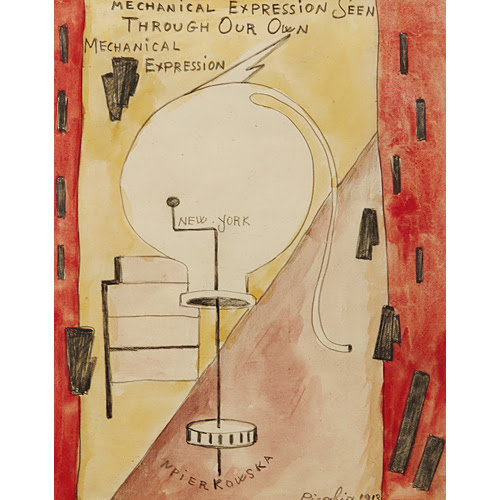

Picabia evokes x-rays in the watercolor “Mechanical Expression Seen Through Our Own Mechanical Expression.” Beginning with a dancer, he selected a symbolic object — a conflation of a Crookes radiometer and an x-ray tube — which he intended as a representation of her according to functional analogy. This anticipates Surrealist parlor games…

The painting’s title uses the terminology of x-ray photography to describe its x-ray view of the city.

Hartley — inspired by Kandinsky’s The Spiritual in Art, Bergson’s theory of the creative role of intuition, William James, esoteric philosophies, etc. — created in 1912–1913 (in Paris) and 1913–1915 (Berlin) a series of lyrical abstractions in which a loosened Cubist structure is scattered with calligraphic lines and occasional mystic symbols. He hoped to create a spiritual art that would suggest the universal and transcend specific meaning. Again — like Saussure.

Immediately prior to and after his Berlin years, Hartley cultivated a style of painting that was moderately figurative. However, the years 1913 to 1915 marked an apogee of abstraction in his career. During these years he developed a completely independent vernacular. His paintings from this period explode off the canvas; they are composed of bright, starkly contrasting colours that directly border one another. The theme around which these works revolve is the First World War. Hartley’s relationship with the Prussian Officer Karl von Freybourg, who died just months after the outbreak of war, led t” Hartley producing such masterworks as “Portrait of a German Officer’ (1914), in which abstract forms and military paraphernalia are densely interwoven into a portrait composed entirely of symbols.

Hilton Kramer calls Kandinsky’s Composition VII (1913) one of the most beautiful paintings that has ever been created in the name of abstraction.

The main theme, which is an oval form intersected by an irregular rectangle, is perceived like the center surrounded by the vortex of colors and forms. Art historians claim that the Composition VII is a combination of several themes, namely: Resurrection, the Judgment Day, the Flood and the Garden of Eden — all expressed symbolically.

The brainchild of Mikhail Larionov and Natalia Goncharova, Rayonism (sometimes translated as Rayism) developed new ways to express energy and movement. From its conception as a subset of Russian Futurism, Rayonism drew from scientific discoveries — Larionov had most likely read Marie Curie’s Radioactivity and The Discovery of Radium, both recently published in Russia — and theoretical conceptions of the fourth dimension.

The adoption of transparency and fractured objects was influenced by changing understandings of the material world through the discovery of x-rays and radioactivity. The world no longer could be thought of as purely solid and concrete. This, in turn, reinforced fourth-dimensional theories of space and experience as a continuum of our observable universe. The “Rayonist Manifesto” was written in 1912. Although short-lived, Rayonism was a crucial step in the development of Russian abstract art.

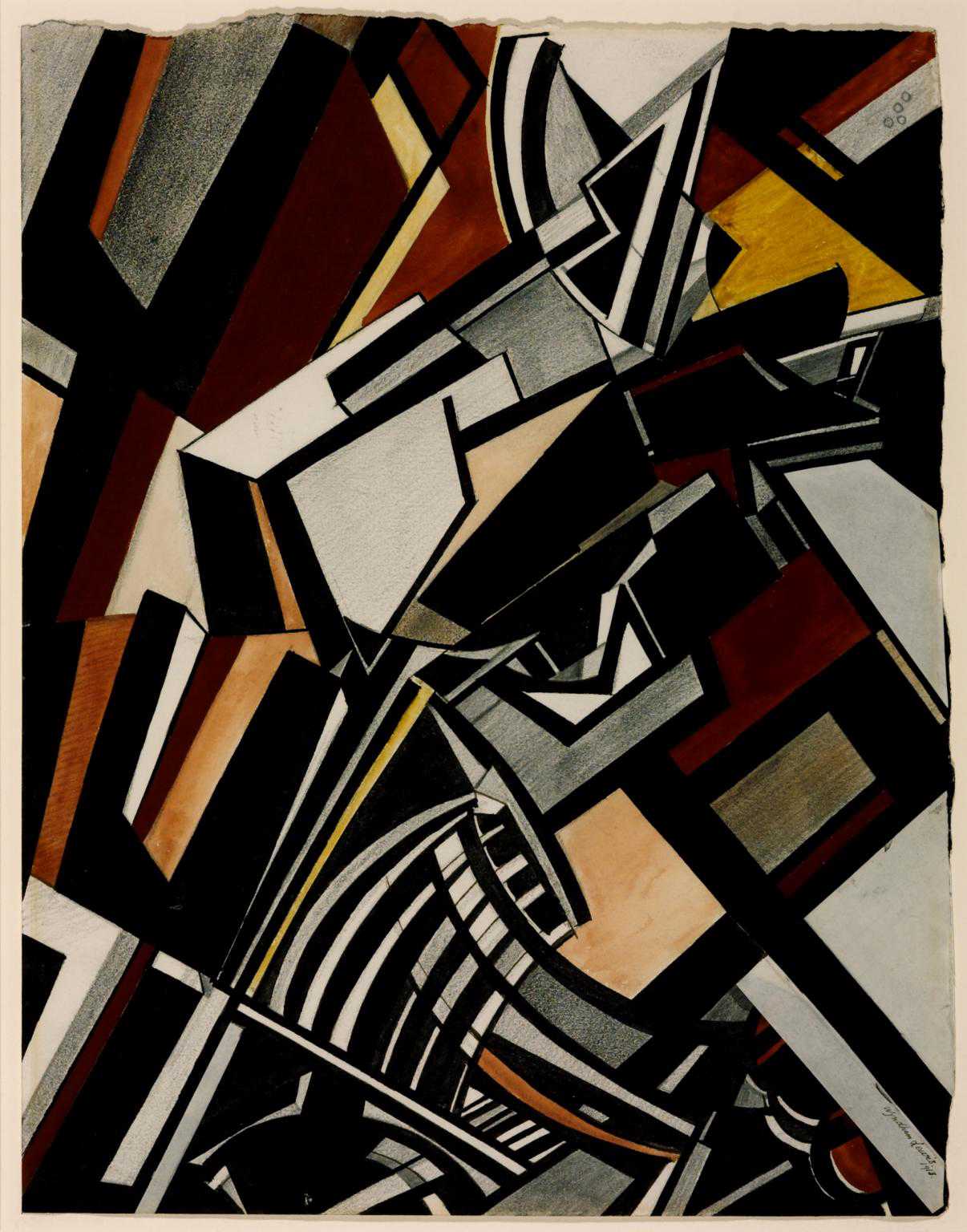

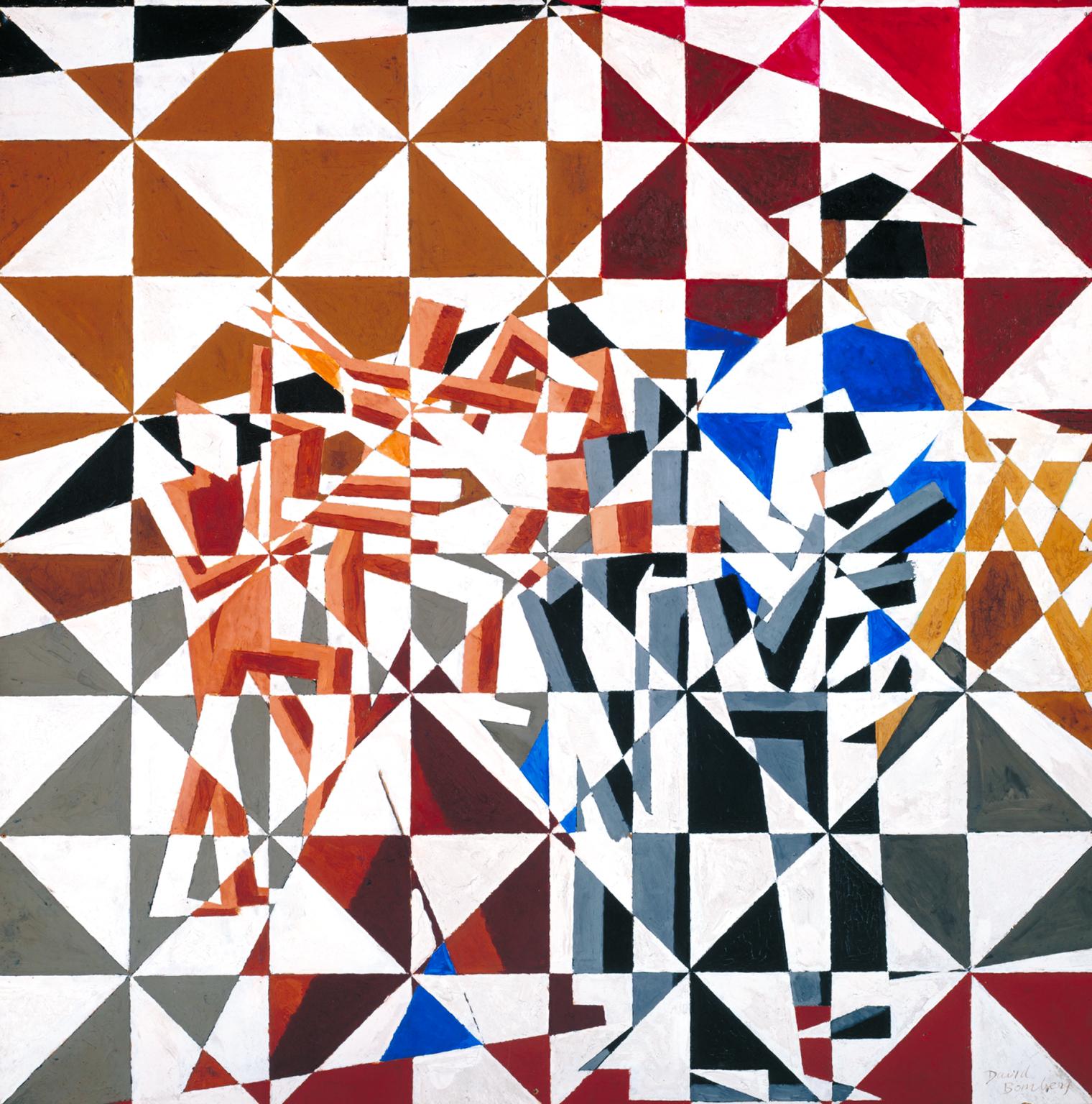

David Bomberg (1890 – 1957) was a British painter, and one of the Whitechapel Boys. Bomberg painted a series of complex geometric compositions combining the influences of cubism and futurism in the years immediately preceding World War I.

Around 1913, Bomberg was interested in both Cubism and Futurism. He wanted to create a new visual language to express his perceptions of the modern industrial city. He wrote: “the new life should find its expression in a new art, which has been stimulated by new perceptions. I want to translate the life of a great city, its motion, its machinery, into an art that shall not be photographic, but expressive.”

Works like this were based on simplified figure drawings. Bomberg superimposed a grid to break up the composition into geometric sections. These were painted different colours, partially obscuring the original subject. Not pure abstraction, then.

From the book MoMA Highlights: 350 Works from the Museum of Modern Art New York (second edition, 2004):

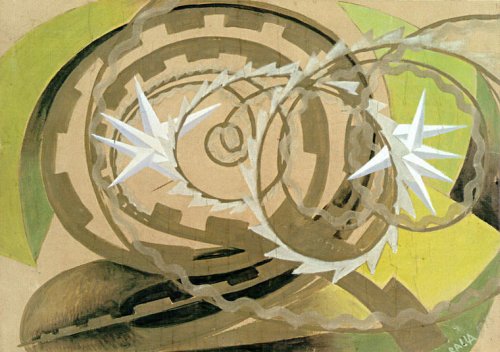

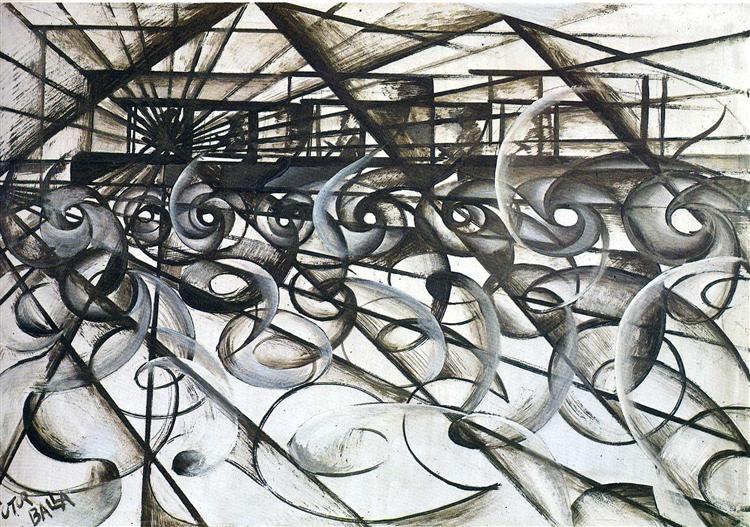

Elaborating on Cubism’s experiment in fracturing forms into planes, the Futurists further tried to make painting answer to movement: while the Cubists were concentrating on still lifes and portraits—in other words, were examining stationary bodies—the Futurists were looking at speed. They said: “The gesture which we would reproduce on canvas shall no longer be a fixed moment in universal dynamism. It shall simply be the dynamic sensation itself.” [Also:] Balla knew the photography of Etiuenne-Jules Marey, which described the movements of animals — including birds — through closely spaced sequences of images; Swifts emulates Marey’s scientific visual analysis, which, in Balla’s time, subjected “dynamic sensation” to scrutiny, but adds to it a sense of exhilarated pleasure.

In 1912, Gino Severini persuaded Boccioni and the other Milan-based futurists to visit Paris, where they encountered cubism. The swirling curves from Boccioni’s earlier work now interact with broad, overlapping planes inspired by Picasso and Braque. Repeated, overlapping curves convey the dynamism of the cyclist’s movement through space. The colors add an ecstatic quality missing from Parisian cubism.

One of four watercolors that Picabia created in the South of France in the Spring of 1914. This group of works was executed following the artist’s return from New York the previous year; Picabia decided to enter four paintings in the now legendary Armory Show of 1913. Immediately after the Armory Show his works were exhibited in Alfred Stieglitz’s gallery ‘291’, where they were enthusiastically received. From a 1913 interview with World Magazine, 1913: “Creative art is not interested in the imitation of objects.”

The painting’s title suggests that Picabia was already moving away from his purist abstract concerns of the previous two years, and towards a Dadaist sensibility that reveled in mockery and badinage.

NOTES ON SUPREMATISM

Malevich — under the influence of P D. Ouspensky, as well as the poet Velimir Khlebnikov — founds Suprematism in 1913.

Suprematist works were intended to represent the concept of a body passing from ordinary three-dimensional space into the fourth dimension. The Russian artists emerging after the turn of the century sought to break away from Cubo-Futurism in search of a new cosmic unity.

Speaking of Khlebnikov, in 1913 he participated in his fellow Russian Futurist poet Aleksei Kruchenykh’s project of developing a non-referential language called Zaum — the purpose being to show that language is indefinite and indeterminate. (In Zaum, “zaum” means “beyonsense.”) The purpose was also to develop a universal language organically, rather than (like Esperanto) artificially. Kruchenykh’s libretto for the Victory over the Sun (see above) is written in Zaum.

Zaum — the idea of a higher perceptual plane, a superconscious state that allows knowledge beyond reason — was adapted from mysticism and Eastern religion.

MORE RADIUM AGE SCI FI ON HILOBROW: RADIUM AGE SERIES from THE MIT PRESS: In-depth info on each book in the series; a sneak peek at what’s coming in the months ahead; the secret identity of the series’ advisory panel; and more. | RADIUM AGE: TIMELINE: Notes on proto-sf publications and related events from 1900–1935. | RADIUM AGE POETRY: Proto-sf and science-related poetry from 1900–1935. | RADIUM AGE 100: A list (now somewhat outdated) of Josh’s 100 favorite proto-sf novels from the genre’s emergent Radium Age | SISTERS OF THE RADIUM AGE: A resource compiled by Lisa Yaszek.