SEMIOPUNK (19)

By:

May 13, 2024

An irregular, ongoing series of posts dedicated to surfacing examples (and predecessors) of the sf subgenre that HILOBROW was the first to name “semiopunk.”

BABEL (2022) | BABEL-17 (1966) | CAMP CONCENTRATION (1968) | A CANTICLE FOR LEIBOWITZ (1959) | CAT’S CRADLE (1963) | COSMONAUT KEEP (2000) | THE DIFFERENT GIRL (2013) | DOOM PATROL (1987–91) | THE EINSTEIN INTERSECTION (1967) | EMBASSYTOWN (2011) | ENGINE SUMMER (1979) | EXPLOITS AND OPINIONS OF DR. FAUSTROLL, PATAPHYSICIAN (1911) | FEERSUM ENDJINN (1994) | FLATLAND (1884) | FRIDAY (1982) | LE GARAGE HERMÉTIQUE (1976–79) | THE GLASS BEAD GAME (1943) | GLASSHOUSE (2006) | GRAVITY’S RAINBOW (1973) | THE HAMPDENSHIRE WONDER (1911) | LORD OF LIGHT (1967) | THE MAN WITH SIX SENSES (1927) | THE MOUNTAIN IN THE SEA (2022) | NINEFOX GAMBIT (2016) | ODD JOHN (1935) | PATTERN RECOGNITION (2003) | THE PLAYER OF GAMES (1988) | RIDDLEY WALKER (1980) | RODERICK (1980–83) | SNOW CRASH (1992) | THE SOFT MACHINE (1961) | SOLARIS (1961) | THE SPACE MERCHANTS (1953) | THE THREE STIGMATA OF PALMER ELDRITCH (1964) | TIME OUT OF JOINT (1959) | UBIK (1969) | VALIS (1981) | A VOYAGE TO ARCTURUS (1920) | VURT (1993) | WHITE NOISE (1985).

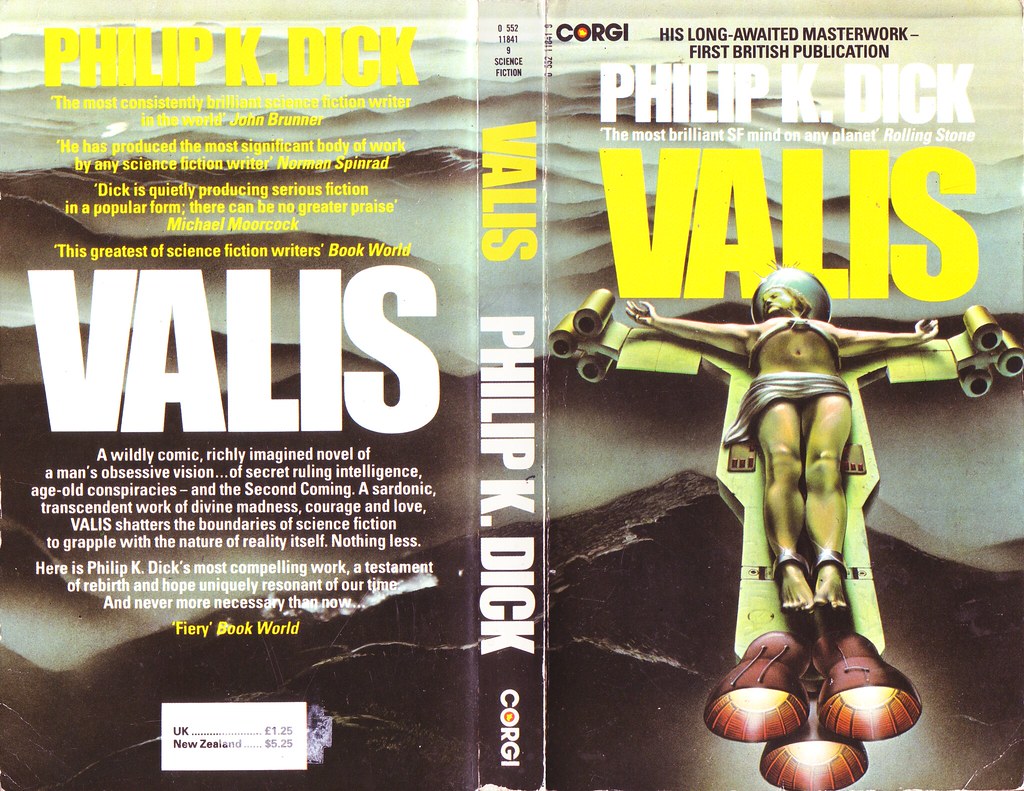

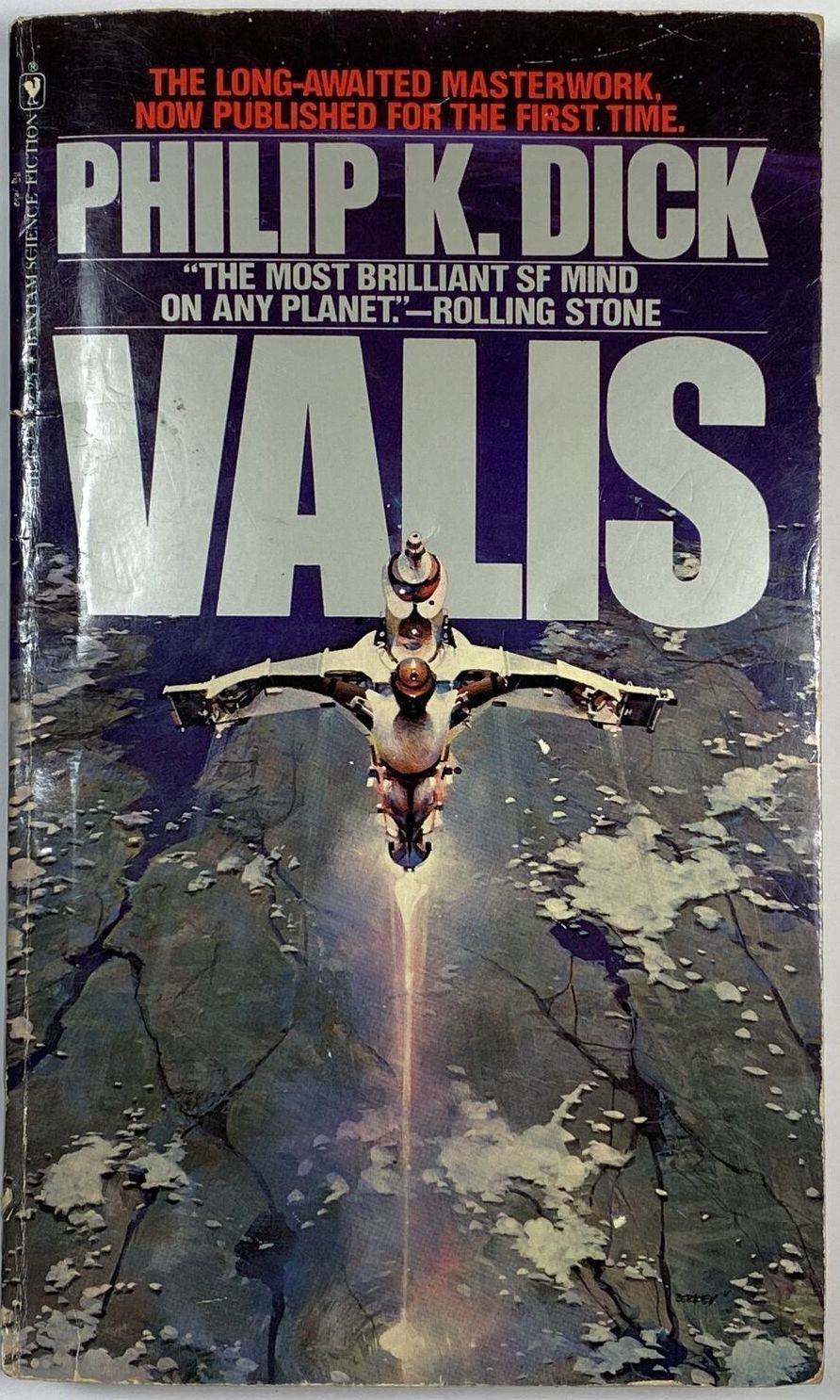

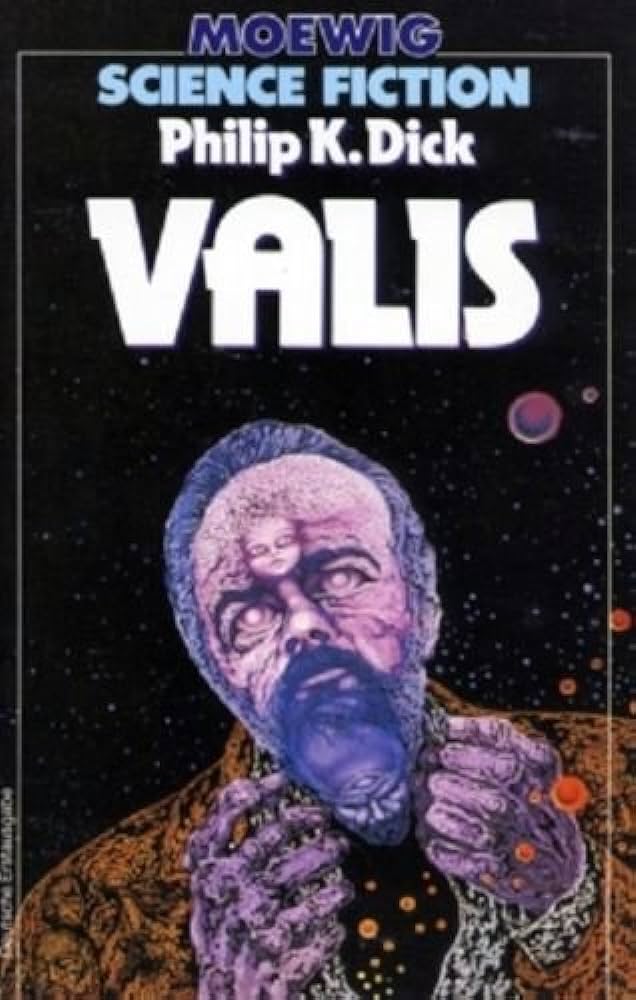

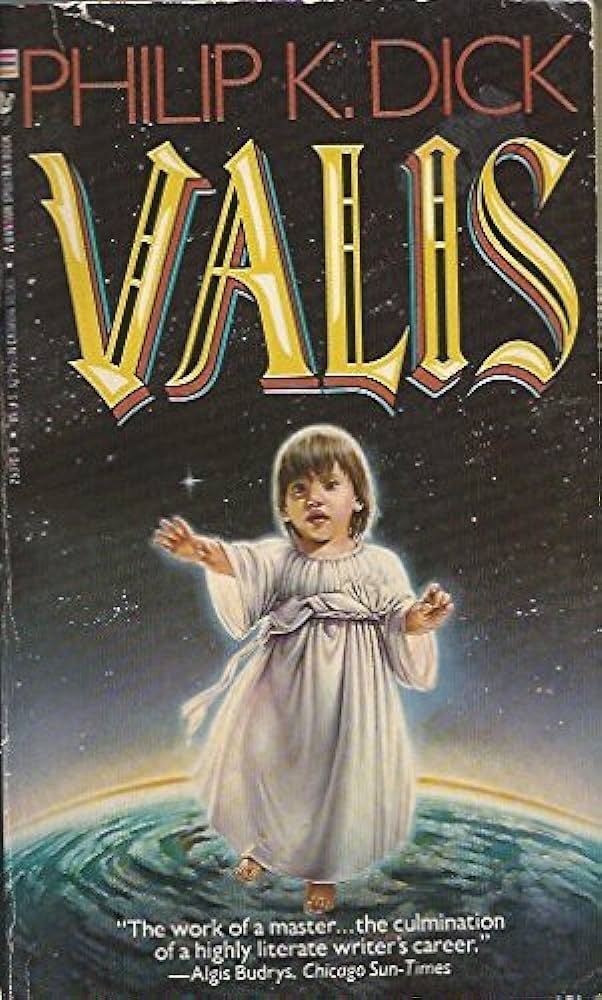

VALIS

The narrator of Philip K. Dick’s VALIS (1981) is “Phil,” a brilliant, self-reflexive sci-fi author who may be a little (or a lot) crazy. Here, he explores not only his own ideas but those of the book’s oddly named protagonist, Horselover Fat, who is also a brilliant, self-reflexive sci-fi author who may or may not be insane.

Fat, it transpires, has received (or believes he has received) a beam of pure reason from “God” — perhaps an alien satellite orbiting Earth? — which has allowed him to see that 1970s California (and America, and the entire world, for that matter) is an illusion. In fact, we’re all blindly toiling in a Black Iron Prison, which is to say an all-pervasive system of social control of which the inmates remain tragically unaware.

The satellite, if there is a satellite, which may have aided the United States in disclosing the Watergate scandal, and the resignation of Richard Nixon in August 1974, appears to be a gnosis-stimulating technology — i.e., one that deploys “disinhibiting stimuli” to communicate, and that uses symbols to trigger the recollection of intrinsic knowledge through the loss of the Black Iron Prison-induced amnesia.

Fat sets off, with a few friends, to seek answers to their questions about God, suffering, art, the mind, the secret history of humankind, and — naturally — about David Bowie (who appeared here as the character Eric Lampton), particularly his 1976 movie The Man Who Fell to Earth. Do superhumans live anonymously among us, using pop culture to stay in touch with one another? Are the pulp sci-fi novels of Philip K. Dick — so paranoid, so uncanny, so trashily written — on to something?

Fun facts: Grant Morrison used VALIS as a source of inspiration for his comic book series The Invisibles (1994–2000), in particular for the Barbelith sentient satellite. And in the “Eggtown” episode of the phildickian TV show Lost (February 21, 2008), John Locke gives Ben Linus this book to read from Ben’s own book shelf.

Thomas M. Disch, writing about VALIS, notes that “the fascination of the book, what’s most artful and confounding about it, is the way the line between Dick and Fat shifts and wavers.” As Disch points out, the second half of the book falls apart, but the first half is an exciting philosophical thriller — a dizzying high-lowbrow roller-coaster ride. Your mileage may vary; some people find the first half a slog, because of the seemingly endless dot-connecting in which Fat indulges himself, and the second half more enjoyable because it gives us more plot, humor, and action.

In addition to being a prolific sf author, Dick was an independent scholar, a real-life version of Roquentin, from Sartre’s 1938 philosophical novel Nausea, that is to say: a melancholic and socially isolated intellectual whose growing alienation and disillusionment lead him to experience hallucinatory revelations about the true nature of people and things. Thus VALIS is replete with references to… Valentinian Gnosticism, the Rose Cross Brotherhood, Zoroastrianism and Buddhism, as well as Biblical writings including the Book of Daniel and Paul’s epistles.

Ancient Greek philosophers are discussed, from the Pre-Socratics (Pythagoras, Xenophanes, Heraclitus, Empedocles, Parmenides) to Plato and Aristotle. More recent philosopers, mystics, psychologists, and scholars of myth and religion whom Fat recontextualizes in light of his revelation include Pascal, Schopenhauer, Jakob Böhme, Paracelsus, Jung and Freud, Mircea Eliade, and Robert Anton Wilson. Interspersed with these highbrow references are lowbrow references to The Grateful Dead, Frank Zappa, and Linda Ronstadt — all of whom are mentioned by name — as well as Bowie and Brian Eno, versions of whom appear (under different names) as characters in the story.

“New patterns of thinking and a stronger sense of intuition will also be a sign that greater access to the field of living intelligence is occurring,” writes Kingsley L. Dennis in a Reality Sandwich essay on VALIS. “This access is the same as, in our older language, direct interaction with nonlocal and non-ordinary states of consciousness.”

The foregoing description suggests why VALIS is a key work of “semiopunk” science fiction. But what particularly intrigues and excites this reader is Dick’s/Fat’s notion of a Vast Active Living Intelligence System (VALIS), which is not merely the near-omniscient, angel-like satellite that aims to help humankind overcome tyranny… but may in fact be a galaxy- or universe-wide network of such satellites, themselves merely the technological instantiation of an “intelligence field” that is sometimes described as cosmic consciousness, superconsciousness, and so forth.

When semioticians attempt to chart the structural workings of a “semiosphere,” they’re taking for granted the existence of an intelligence field of sorts — not a cosmic one, by any means, but a local version of that sort of thing. And like VALIS, the satellite, we use symbols and “disinhibiting stimuli” to communicate what we’ve learned to those who haven’t developed the same organs of perception (if you will). Like VALIS, we’re not introducing something new so much as we are helping our clients to “recollect” implicit, intuitive knowledge that they possess but can’t access. Also like VALIS, we’re none of us particularly good at this sort of transmission.

It isn’t necessary, in order to enjoy VALIS, to know this, but: On February 3, 1974, Dick suddenly experienced a flood of hallucinatory visions for no apparent reason. This terrifying experience suggested to him that the far-out theories he’d advanced since the 1950s in his politically and epistemologically paranoid stories and pulp novels — which by then amounted to nearly 50 titles — were, in fact, completely and utterly true. Did the ideas in these books add up to a single, overarching theory? In the remaining eight years of his life Dick devoted thousands of pages of his “Exegesis,” a journal explicating the “2-3-74” epiphany, to answering that question.

Like the bewildered characters in his novels, Dick tested out conjecture after conjecture, each one “more cunning, more exciting, and more fucked,” as he put it, than the one before. Although he found none of these ultimately satisfying, there was a common thread. As he would write in the “Exegesis,” on 2-3-74 he was lifted “from the limitations of the space-time matrix,” and instantly recognized that “the world around me was cardboard, a fake” — that it was, in fact, a “Black Iron Prison” (BIP, for short). In that instant, Dick recounts, he felt impelled to take on “in battle, as a champion of all human spirits in thrall, every evil, every Iron Imprisoning Thing.”

Commercial semioticians are rarely in a position to use their powers to this sort of liberatory end… though in nearly every project there are opportunities to “move the needle” at least a little.

VALIS is the first installment in a never-completed trilogy of novels fictionalizing the philosophical explorations Dick made into his 2-3-74 experience via The Exegesis. The Divine Invasion appeared in 1981. The planned third novel, The Owl in Daylight, had not yet taken definite shape at the time of the author’s death in 1981. However, Dick’s posthumously published final novel, The Transmigration of Timothy Archer (1982), builds on similar themes.

JOSH GLENN’S *BEST ADVENTURES* LISTS: BEST 250 ADVENTURES OF THE 20TH CENTURY | 100 BEST OUGHTS ADVENTURES | 100 BEST RADIUM AGE (PROTO-)SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST TEENS ADVENTURES | 100 BEST TWENTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST THIRTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST GOLDEN AGE SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST FORTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST FIFTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST SIXTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST NEW WAVE SCI FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST SEVENTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST EIGHTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST DIAMOND AGE SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST NINETIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST HADRON AGE SCI-FI ADVENTURES.