SEMIOPUNK (18)

By:

May 2, 2024

An irregular, ongoing series of posts dedicated to surfacing examples (and predecessors) of the sf subgenre that HILOBROW was the first to name “semiopunk.”

BABEL (2022) | BABEL-17 (1966) | CAMP CONCENTRATION (1968) | A CANTICLE FOR LEIBOWITZ (1959) | CAT’S CRADLE (1963) | COSMONAUT KEEP (2000) | THE DIFFERENT GIRL (2013) | DOOM PATROL (1987–91) | THE EINSTEIN INTERSECTION (1967) | EMBASSYTOWN (2011) | ENGINE SUMMER (1979) | EXPLOITS AND OPINIONS OF DR. FAUSTROLL, PATAPHYSICIAN (1911) | FEERSUM ENDJINN (1994) | FLATLAND (1884) | FRIDAY (1982) | LE GARAGE HERMÉTIQUE (1976–79) | THE GLASS BEAD GAME (1943) | GLASSHOUSE (2006) | GRAVITY’S RAINBOW (1973) | THE HAMPDENSHIRE WONDER (1911) | LORD OF LIGHT (1967) | THE MAN WITH SIX SENSES (1927) | THE MOUNTAIN IN THE SEA (2022) | NINEFOX GAMBIT (2016) | ODD JOHN (1935) | PATTERN RECOGNITION (2003) | THE PLAYER OF GAMES (1988) | RIDDLEY WALKER (1980) | RODERICK (1980–83) | SNOW CRASH (1992) | THE SOFT MACHINE (1961) | SOLARIS (1961) | THE SPACE MERCHANTS (1953) | THE THREE STIGMATA OF PALMER ELDRITCH (1964) | TIME OUT OF JOINT (1959) | UBIK (1969) | VALIS (1981) | A VOYAGE TO ARCTURUS (1920) | VURT (1993) | WHITE NOISE (1985).

LE GARAGE HERMÉTIQUE

In 1974, Alejandro Jodorowsky invited the French bande dessinée artist Jean Giraud, at that time known for his work on the long-running Western comic Fort Navajo (aka Blueberry), to create set and character designs for his adaptation of Frank Herbert’s Dune. (Alas, one of our civilization’s great unfinished masterworks.) That same year, Giraud co-founded Les Humanoïdes Associés, a comics collective that immediately débuted the paradigm-shattering comics magazine Métal Hurlant.

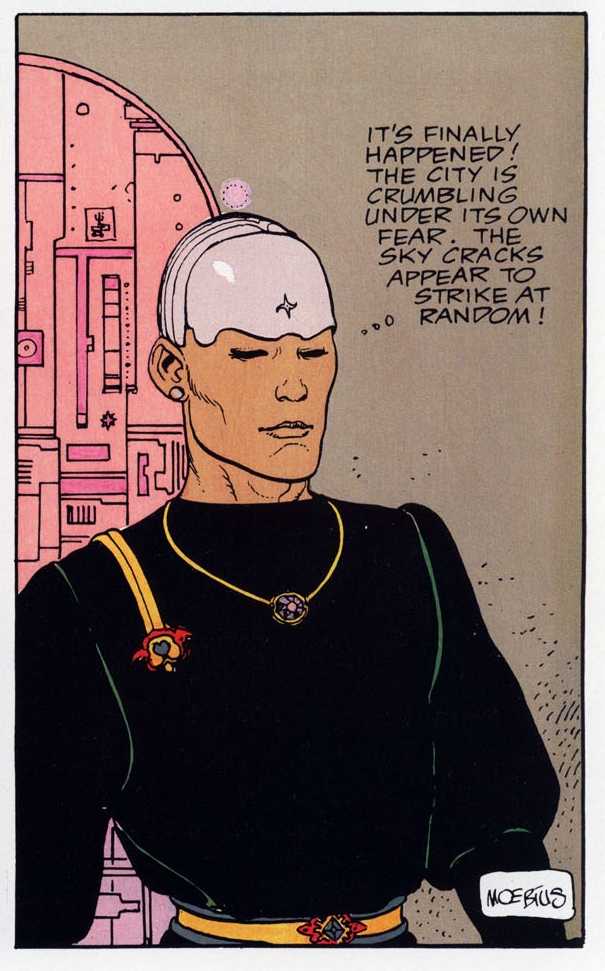

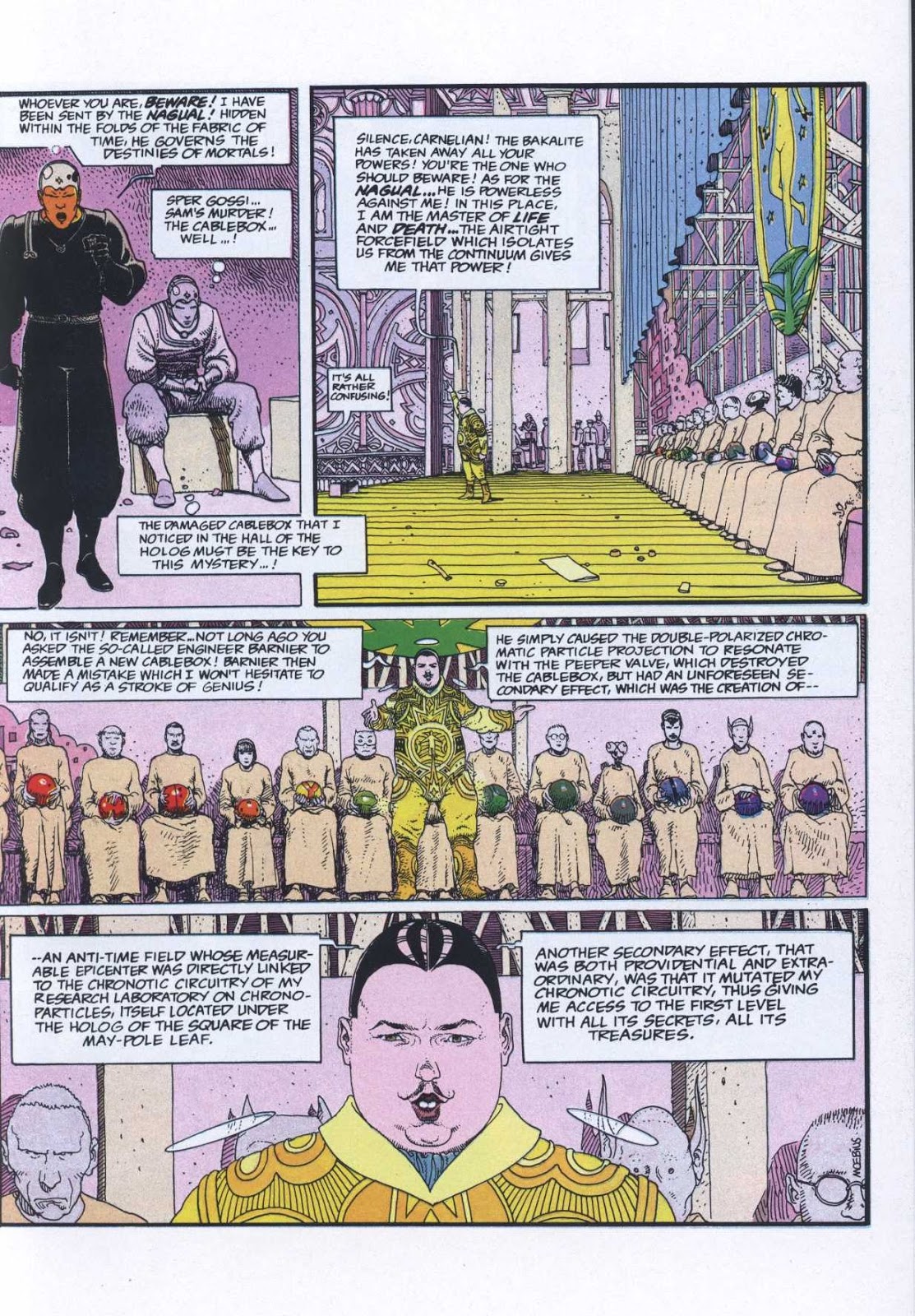

Working under the nom de plume “Moebius,” via the black-and-white pages of Métal Hurlant Giraud would give us first the Arzach stories (1974–1975) — being the wordless adventures of a warrior riding a pterodactyl-ish creature through fantastical landscapes. (Miyazaki’s Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind is one of many subsequent productions, across various media, that would draw inspiration from the Arzach stories.) A few years later, Giraud would team up again with Jodorowsky to create L’Incal (1980–1985), an occult space opera — featuring massive spacecraft, technopriests, rubbish-dwelling mutants, giant jellyfish, wizened gurus perched on floating crystals, and “necro-panzers” — offering a glimpse of what Jodorowsky’s Dune might have been.* Though (intentionally) goofy in spots, L’Incal is one of the best comic books in the medium’s history.

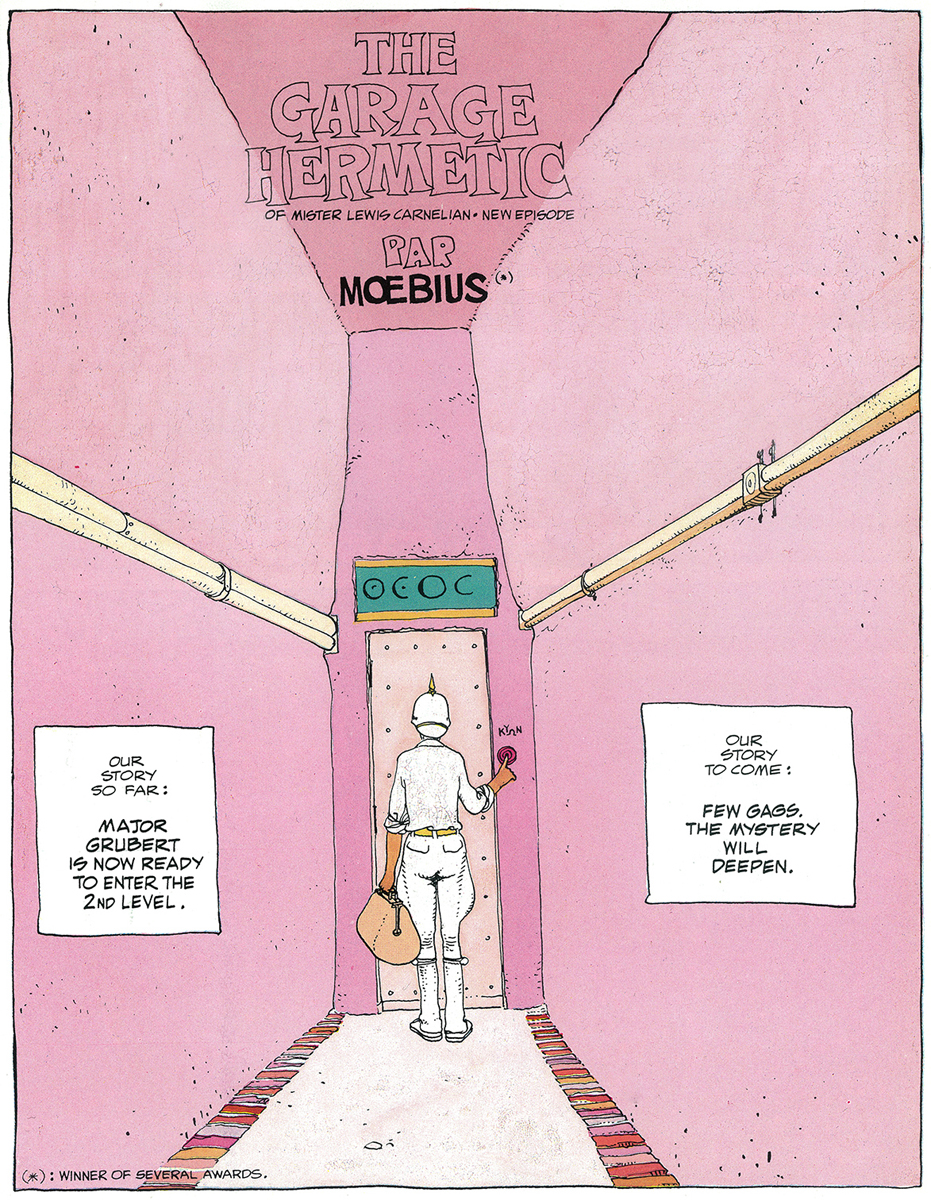

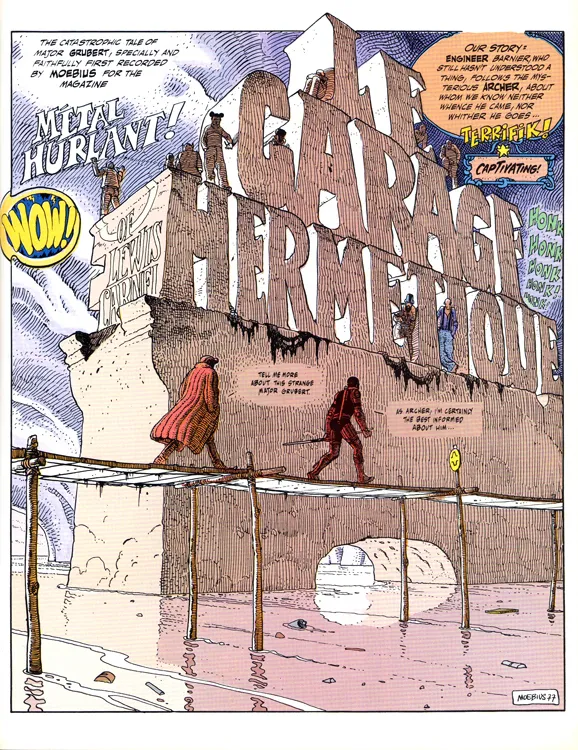

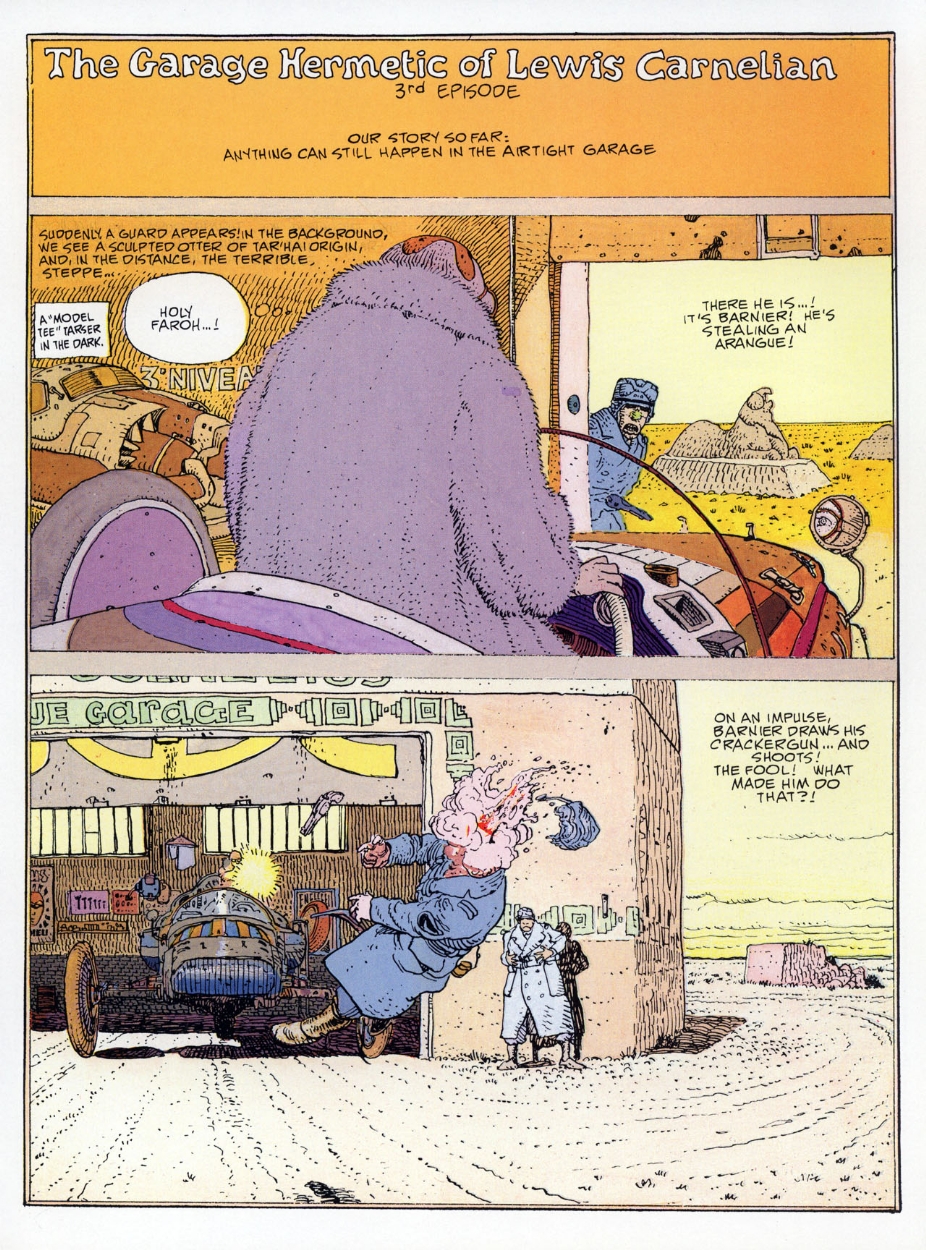

In between these literally epic achievements, Giraud wrote and illustrated Le Garage Hermétique (1976–1979), an eccentric sci-fi picaresque known in English by the technically accurate if one-dimensional title The Airtight Garage; The Garage Hermetic is a preferable title, for reasons to be explored. I’ve re-read Le Garage Hermétique often, since I first encountered it as a college student — in the 1987 Marvel/Epic full-color edition, as well as in disparate back issues of Métal Hurlant. Giraud’s story activates a rarified pleasure center in my brain which, alas, is all too rarely activated — except when I’m engaged in semiotic analysis.

“Isn’t yesterday crushed, like a dove / By a motorized vehicle / Emerging madly from the garage?” — Anatoly Marienhof, “October” (c. 1918)

Here are a few notes about the events chronicled in the first part of Giraud’s story — which was originally serialized 2–6 pages at a time.

Barnier, an engineer in a science-fictional garage, is overhauling a “cable box” — a revolutionary technology of some sort that’s also a starfaring vehicle — when they accidentally damage it. (Or was it a case of sabotage?) Rather than face the wrath of Jerry Cornelius / Lewis Carnelian, they flee — impulsively killing a guard en route. Meanwhile, Carnelian has been driving across a desert for weeks, en route to the mysterious capital city Armjourth. In orbit, meanwhile, we discover the Ciguri, spaceship HQ of the dapper, mustachioed Major Grubert (and his fiancée, Malvina). Learning that “all the levels” of his former hideaway — the asteroid within which the story’s action takes place — have been infiltrated (by Carnelian and his team), he despatches a spy, Samuel Mohad, to assess the situation. Why doesn’t Grubert go to the asteroid himself? Because “It may be a Bakalite trick.” (This is a reference to a previous Moebius story that appeared in Métal Hurlant in 1976, “Le Major Fatal,” in which the Major robs and assassinates a Bakalite.)

A note, here, about Cornelius/Carnelian. Michael Moorcock created the anarcho-hipster adventurer Jerry Cornelius, protagonist of The English Assassin (1972) and other novels. Cornelius is an agent of the cosmic force that opposes culture, civilization, empire, religion, and other manifestations of Order; his presence in a story causes it to become entropic. In a crack at open-source, shared-world building, Moorcock encouraged other authors and artists to use Cornelius; several — including Norman Spinrad, Brian Aldiss, M. John Harrison, and Giraud — would take him up on the offer. The title of Le Garage Hermétique was originally Le Garage Hermétique de Jerry Cornelius. Giraud would soon drop that clause from the title; and in later editions of the comic he’d rename the character “Lewis Carnelian.” (The entropy, however, would remain.) Readers at the time would have likely picked up on this stuff… and therefore they would have understood Grubert to be an agent of Order.

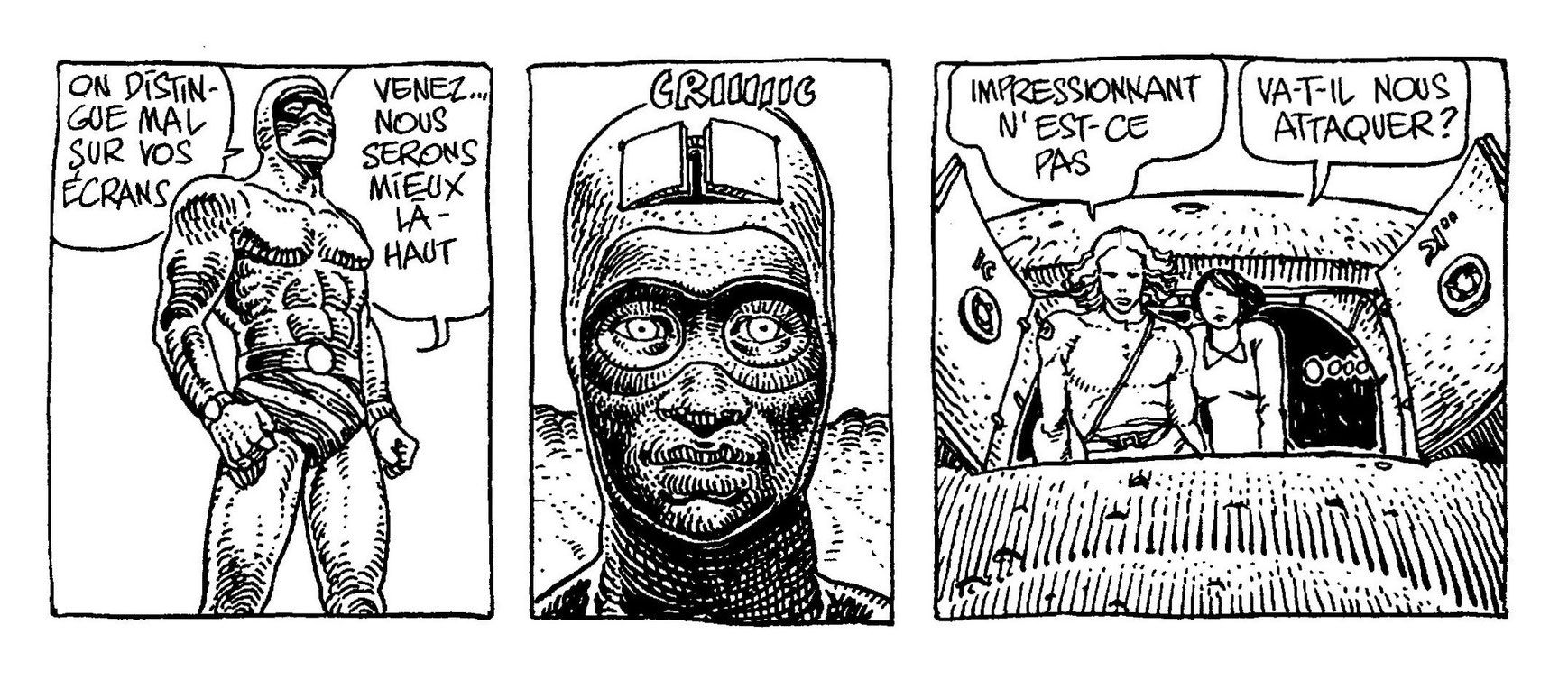

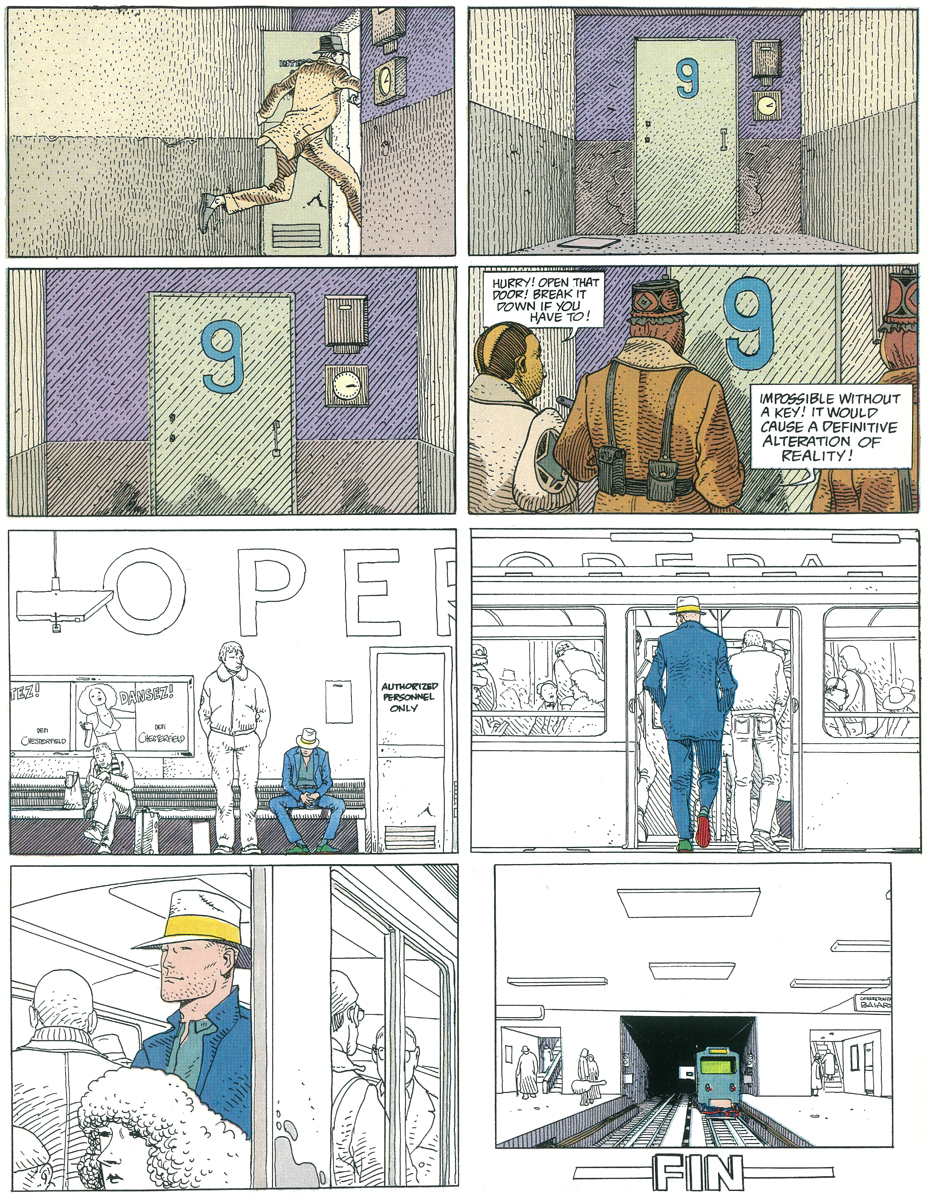

We next find Sam and Okania, a stowaway who’s in love with him, traversing the asteroid’s desert biome, ensconced within the head of a giant robot (whose design pays homage to Lee Falk’s Phantom — one of many such in-jokes) “designed to reach the first level” — i.e., the asteroid’s surface. Something that Sam says gives us the impression that Grubert may be the creator of this asteroid; he’s a story teller, and the asteroid the story. Inside a medieval-looking building, Sam and Okania pass through a “lock” allowing them access to the second level. Back aboard the Ciguri, we learn that Carnelian hails from Earth. Grubert believes that the “Nagual” has discovered him at last and sent Carnelian after him; so he decides to face him directly.

[By the way, in the original serialized version of the story, although there are multiple levels to the asteroid, it’s quite difficult to ascertain which level is which. I’m referring to the 1987 edition.]

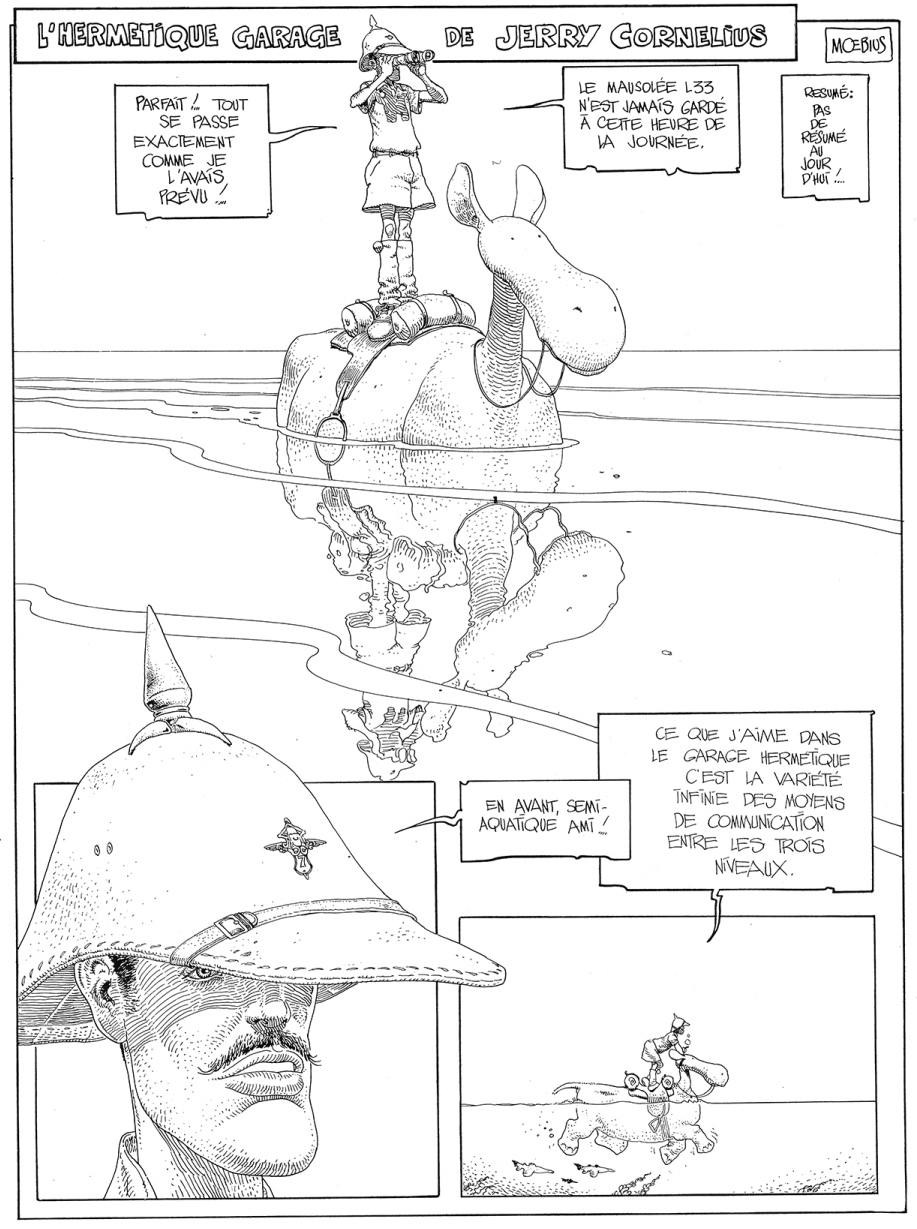

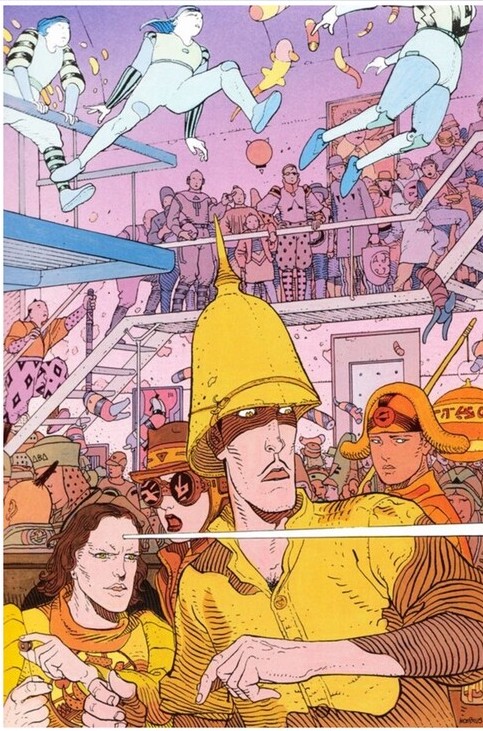

When we next spot Grubert, he’s riding a cartoonish creature through a vast veld. He articulates a stoic philosophy while being subjected to humiliations. Meanwhile, on the second level, Sam and Okania are now aboard a steam-powered train headed towards Armjourth. (“Except for the usual details, the impression of reality is striking!” marvels Okania.) One of Carnelian’s agents, in a plane, bombs the train. Engineer Barnier, meanwhile, is lost in the maze of the singing caverns. Grubert continues to move forward, musing, “What I love about the Garage Hermetic is the infinite variety of passages between the levels” — which offers us some sense of the asteroid’s structure. At this point we realize that the Garage Hermetic is Grubert’s name for the asteroid.

An aside, here, on the comic’s title. To be sure, hermétique suggests “airtight,” which makes perfect sense when you consider that this space opera is set within a hollow-Earth asteroid (one whose various levels feature, e.g., desolate desert and forest biomes, a bustling metropolis, and a world made of machines). So I can understand why it’s been translated as The Airtight Garage. But Giraud’s use of the term is also intended to suggest Hermeticism — i.e., the occult philosophical system associated with the notion that our visible everyday world is but a reflection of a truer, invisible reality. Grubert’s “garage” — this pocket universe that Giraud’s characters explore — is hermétique in both senses of the term.

Soon Grubert arrives at a “lock” that will give him access to the second level… and Armjourth. (Where everyone gawks at him — do they recognize him as their creator?) He’s arranged to meet someone named Graad. Barnier, meanwhile, is rescued from the singing caverns by a masked archer; they are accompanied on their trek by a “barcoll” creature on a stretcher. Exhausted in his search for Graad (who will turn out to be Okania’s father), through the seedier sections of Armjourth, Grubert falls asleep; this is surprising, a couple of Armjourth denizens observe, considering that he is a “demigod.” (Demiurge, more like it.) Worried for his safety, when one of the Armjourthians (who bears a striking resemblance to Hercule Poirot) aims a pistol at Grubert’s head, the major’s team aboard the Ciguri wakes him up remotely.

The Armjourthian, who introduces himself as Ardant Echoy (but whom someone else identifies as “Sper”) brings Grubert to the building where the train on which Sam and Okania were riding when it was bombed is being repaired; en route, Grubert spots the damaged cable box, now emitting some sort of weird energy. Meanwhile, the barcoll reveals to Barnier that the cable box was in fact sabotaged… by Grubert. The archer explains that Grubert is the world’s creator, and Carnelian is his enemy — but the world’s inhabitants want independence from both!

Things get far, far more complex than this… But let’s stop here. I haven’t even talked about Giraud’s dazzling artwork, which stroboscopically flickers from one style and technique to another — now realistic, now cartoonish; now science fiction, now fantasy, now Western, now Boy’s Own Adventure; now vast and mysterious, now closeup. It’s a bravura performance in the realm of Kirby, Hergé, or Clowes.

Why did Grubert create, then remove himself from this “pocket universe”? Why has Carnelian infiltrated the Garage Hermetic? And why is Grubert pursuing Carnelian? (Is it a coincidence that Jerry Cornelius and Jesus Christ share the same initials? Or might the Garage Hermetic represent three “levels” of the human mind?) What is a Nagual… and a Bakalite? What might the cable box (perhaps the ultimate MacGuffin) and its accidental disrepair portend? Will Chaos triumph over Order — and if so, are we supposed to regard that as a positive outcome? What’s the deal with Grubert’s pith helmet? Today’s readers tend to find these unanswered questions frustrating. Giraud playfully frustrates our desire for closure… which is part of the fun.

In order to explain the peculiar pleasure that I derive from Le Garage Hermétique, its crucial to explore Giraud’s method in composing the story.

“I drew the first two pages with the feeling of making up a big joke, a complete mystery, something that could not possibly lead anywhere,” he explains in his introduction to the 1987 Marvel/Epic edition. Asked some time later to complete the story so that it might be published in Métal Hurlant, a panicked Giraud — who’d handed in the first two pages, and couldn’t remember much about them — dashed off another two pages “to buy myself more time.” Though these first two chunks are set in and around a science-fictional garage (hence the title, which does not originally seem to have been intended to describe the world), in other respects the story lacked continuity; only with the third episode would Giraud begin to connect the dots and establish continuity.

The high-wire, in certain respects unpleasant and stressful challenge of writing and illustrating the story’s third episode, Giraud discovered, was… thrilling. That part of his brain which enjoyed making connections, discovering and inventing meaning, was vigorously stimulated. “Soon I decided to experiment with the story telling itself by challenging myself every month to solve the continuity problems that I had introduced in previous months,” he’d recount. Creating and then resolving discontinuity would from that point on be a feature of Le Garage Hermétique, not a bug.

“By creating this feeling of permanent insecurity, I was forced to experience the total joy of creating a continuity,” he’d go on to recall. “Every month, I would try very hard to recreate a coherent story from the existing elements. Then, I would break them apart again in order to create again a feeling of insecurity, so that, the next month, I would again have to pick up the pieces and do it again, and so on until the end of the story.”

My fellow semioticians will understand exactly what Giraud means when he describes “the total joy of creating a continuity.” The pioneering semiotician and logician C.S. Peirce once compared the feeling of having arrived successfully at a “hypothetic inference” (connecting the dots) with the “peculiar musical emotion” that one experiences when hearing the otherwise discordant instruments of an orchestra achieve a harmonious musical blend. By breaking and remaking the story’s continuity again and again, Giraud devised a means of experiencing this painful/pleasurable musical emotion over and over again…

We semioticians can’t really replicate this sort of thing. True, during the course of our work, as we catch glimpses of the semiosphere schema we’re developing, we experience flashes of this continuity-joy; and those of us who are rigorously hermeneutic — toggling back and forth between local details and the big picture — can prolong this experience to some extent. But eventually it’s all over, our schema completed.

Not so for Le Garage Hermétique. True, in its final fifteen pages, which Giraud wrote and drew in a single sitting, the story’s various threads finally intertwine more or less tightly (no matter how absurd or unlikely the result). But as Giraud points out in his 1987 introduction, “the story ends on yet another open-ended sequence, which introduces a potentially unlimited incoherence factor.” What a concept — an Incoherence Factor (in this case, one named Lewis Carnelian) purposely injected into a story, forever disrupting and deconstructing the story teller’s best efforts at coherence.

HILOBROW readers know that I’m a fan of what I’ve named “apophenic adventures.” In which the adventurer doesn’t merely seek to surface a single answer or truth… but must struggle with questions such as Does anything mean anything? Giraud’s story is deeply engaging and satisfying because — following in the footsteps of Samuel R. Delany’s Babel-17 — it uses space-opera elements, and thus at a structural level promises the reader easily-defined heroes and villains, the resolution of tension via decisive (and violent) right action, and so forth… but then fails to deliver on these promises. Doesn’t merely fail to deliver, but forces us to ask ourselves why we think such promises are worth keeping, why we’re attracted to such story-telling….

* “Jodoverse” prequels and sequels include Before the Incal (1988–1995, ill. Zoran Janjetov), After the Incal (2000, ill. Giraud), and Final Incal (2008–2014, ill. José Ladrönn); and spinoffs include The Metabarons (1992–2003), The Technopriests (1998–2006), and Megalex. PS: Taika Waititi has signed on to co-write and direct the Incal movie — wow!

JOSH GLENN’S *BEST ADVENTURES* LISTS: BEST 250 ADVENTURES OF THE 20TH CENTURY | 100 BEST OUGHTS ADVENTURES | 100 BEST RADIUM AGE (PROTO-)SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST TEENS ADVENTURES | 100 BEST TWENTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST THIRTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST GOLDEN AGE SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST FORTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST FIFTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST SIXTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST NEW WAVE SCI FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST SEVENTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST EIGHTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST DIAMOND AGE SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST NINETIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST HADRON AGE SCI-FI ADVENTURES.