RADIUM AGE ART (1911)

By:

April 24, 2024

A series of notes regarding proto sf-adjacent artwork created during the sf genre’s emergent Radium Age (1900–1935). Very much a work-in-progress. Curation and categorization by Josh Glenn, whose notes are rough-and-ready — and in some cases, no doubt, improperly attributed. Also see these series: RADIUM AGE TIMELINE and RADIUM AGE POETRY.

RADIUM AGE ART: 1900 | 1901 | 1902 | 1903 | 1904 | 1905 | 1906 | 1907 | 1908 | 1909 | 1910 | 1911 | 1912 | 1913 | 1914 | 1915 | 1916 | 1917 | 1918 | 1919 | 1920 | 1921 | 1922 | 1923 | 1924 | 1925 | 1926 | 1927 | 1928 | 1929 | 1930 | 1931 | 1932 | 1933 | 1934 | 1935 | THEMATIC INDEX.

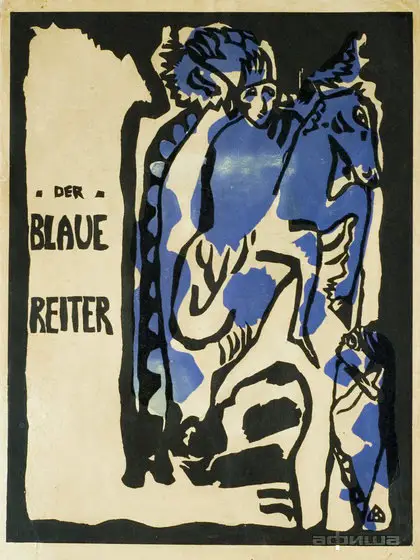

In Munich, German Expressionism is the cutting-edge style, as practised by Der Blaue Reiter (1911-14). A much looser association of artists than Brücke, it attracts a diverse group of individuals — von Jawlensky, Kandinsky, Klee, Marc, Macke — most of whom share an interest in color theory, a tendency toward abstraction, and an interest in “spiritual” values. Like the Brücke artists, Kandinsky and Marc believe that art can help bring about a new age (that is, a more spiritual age).

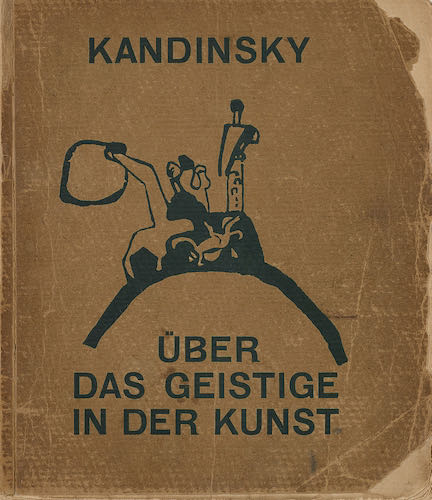

Kandinsky’s 1911/1912 book Über das Geistige in der Kunst (translated 1914 as Concerning the Spiritual in Art), heavily influenced by the Theosophical book Thought-Forms, is a defense and promotion of abstract art. A seminal text in the history of modern art, it will spark widespread interest in abstraction.

Note from MOMA’s “Inventing Abstraction” series:

Beginning in late 1911 and across the course of the next year, a series of artists including Vasily Kandinsky, Fernard Léger, Robert Delaunay, Frantisek Kupka, and Francis Picabia exhibited works that marked the beginning of something radically new: they dispensed with recognizable subject matter.

Clement Greenberg will write, in his essay “Avant-Garde and Kitsch”:

Picasso, Braque, Mondrian, Miro, Kandinsky, Brancusi, even Klee, Matisse and Cézanne derive their chief inspiration from the medium they work in. The excitement of their art seems to lie most of all in its pure preoccupation with the invention and arrangement of spaces, surfaces, shapes, colors, etc., to the exclusion of whatever is not necessarily implicated in these factors.

According to Greenberg, avant-garde painters such as these are responding to kitsch: “popular, commercial art and literature with their chromeotypes, magazine covers, illustrations, ads, slick and pulp fiction, comics, Tin Pan Alley music, tap dancing, Hollywood movies, etc., etc.” He goes on to say:

Kitsch, using for raw material the debased and academicized simulacra of genuine culture, welcomes and cultivates this insensibility. It is the source of its profits. Kitsch is mechanical and operates by formulas. Kitsch is vicarious experience and faked sensations. Kitsch changes according to style, but remains always the same. Kitsch is the epitome of all that is spurious in the life of our times. Kitsch pretends to demand nothing of its customers except their money — not even their time.

Also: “Kitsch is deceptive. It has many different levels, and some of them are high enough to be dangerous to the naive seeker of true light.”

Apollinaire’s 1911 lecture on modern painting, which eventually becomes three chapters of his 1913 book Les peintres cubistes, compares the new painters to the late-19th century geometers for whom the three dimensions of Euclid’s geometry had become insufficient. The fourth dimension, he writes, “represents the immensity of space eternalizing itself in all directions at any given moment. It is space itself, the dimension of the infinite; the fourth dimension endows objects with plasticity.” That is to say, those visionaries able to see from the perspective of the fourth dimension perceive our world in a far-out, “infinite” way and — in the manner of primitive artists, who paint and sculpt what they think rather than what they literally see — depict it as such.

Albert Gleizes’ “L’Art et ses représentants. Jean Metzinger” (1911). The essay argues that Metzinger’s intention is “to inscribe the total image,” i.e., an image combining “the evidence of perception” with “a new [intruitive] truth, born from what [the artist’s] intelligence permits him to know.” Such knowledge, writes one critic, is “the accumulation of an all-round study of things, and so it was conveyed by the combination of multiple viewpoints in a single image.” He continues, “This accumulation of fragmented aspects would be given ‘equilibrium’ by a geometric, a ‘cubic’ structure.”

“The cubists play a role in art today analogous to that sustained so effectively in the political and social arena by the apostles of anti-militarism and organized sabotage,” laments the critic Gabriel Mourney in his review of the Salon d’Automne of 1911 for Le Journal, going on to describe these artists as “the anarchists and saboteurs of French painting.” See: David Cottington’s Cubism in the Shadow of War: The Avant-garde and Politics in Paris 1905-1914 (1998).

Active from 1911 to around 1914, members of the Section d’Or (also known as Groupe de Puteaux or Puteaux Group) came to prominence in the wake of their controversial showing at the Salon des Indépendants in the spring of 1911. Based in the Parisian suburbs, the group holds regular meetings at the home of the Duchamp brothers in Puteaux and at the studio of Albert Gleizes in Courbevoie. More info below.

Posthumous publication of Jarry’s Faustroll.

Marie Curie is awarded a second Nobel Prize, this time in Chemistry — for her discovery of the elements of radium and polonium. She is the first person to win or share two Nobel Prizes.

“In 1911 Rutherford introduced the greatest change in our idea of matter since the time of Democritus… the most arresting change is not the rearrangement of space and time by Einstein but the dissolution of all that we regard as most solid into tiny specks floating in a void. That gives an abrupt jar to those who think that things are more or less what they seem.” — Eddington’s The Nature of the Physical World (1928)

Rutherford’s atom, as depicted in a 1911 paper, is made up of a central charge (the modern atomic nucleus, though Rutherford did not use the term “nucleus”) surrounded by a cloud of (presumably) orbiting electrons. The Rutherford model supplanted the “plum-pudding” atomic model of J.J. Thomson, in which the electrons were embedded in a positively charged atom like plums in a pudding. Based wholly on classical physics, the Rutherford model itself was superseded in a few years by the Bohr atomic model, which incorporated some early quantum theory. (In modern quantum mechanics, the electron in hydrogen is a spherical cloud of probability that grows denser near the “nucleus.”)

See: RADIUM AGE: 1911

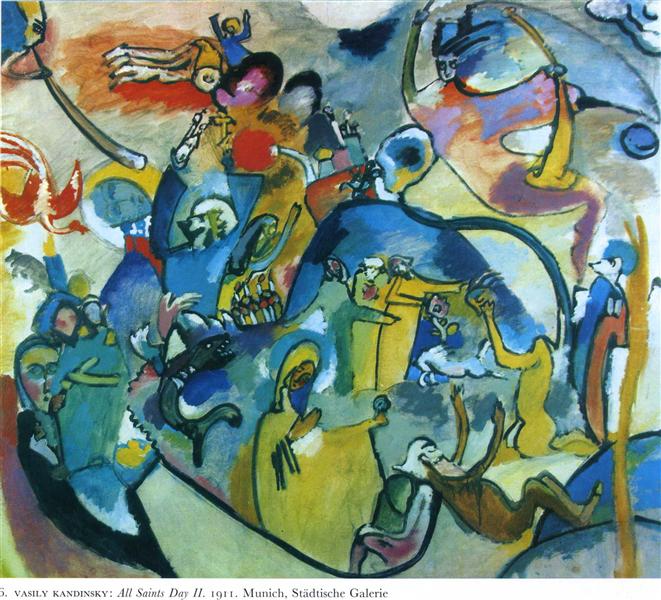

An apocalyptic scene inspired by the Book of Revelation. Angels with trumpets in the upper corners. A haloed saint is pulled across the sky in a chariot. The beast emerging from the sea humps its way up a hillside. New Jerusalem atop another hill. Revelation’s saints, including a beheaded martyr, gesticulate frenziedly. Compare with 1912’s Last Judgment.

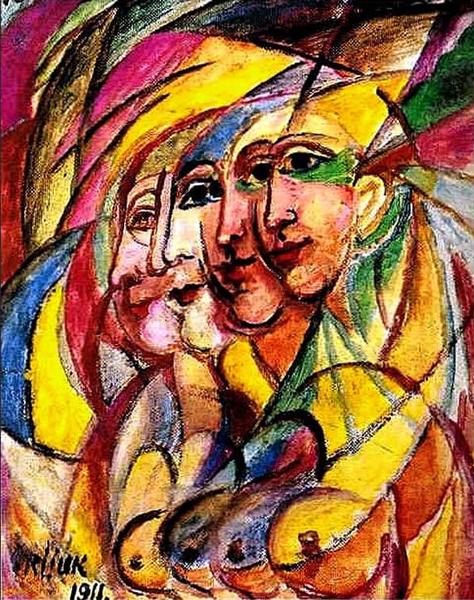

Albert Gleizes, Jean Metzinger, Robert Delaunay, Henri le Fauconnier, Fernand Léger and Marie Laurencin’s 1911 Salon des Indépendants show publicizes the Section d’Or collective. The Salon de la Section d’Or, held October 1912, will be even more notable… and will bring Alexander Archipenko, Joseph Csaky, Roger de La Fresnaye, Juan Gris, and Jean Marchand into their circle. František Kupka and Francis Picabia were in the mix, too, along with the Duchamp brothers, who exhibited under the names of Jacques Villon, Marcel Duchamp, and Raymond Duchamp-Villon.

Also see: Hélène Oettingen, Alexander Archipenko, Constantin Brâncuși, Joseph Csaky, Alexandra Exter (or Ekster), Marthe Donas, Pierre Dumont, Natalia Goncharova, Jean Lambert-Rucki, André Lhote, Louis Marcoussis, André Mare, Irène Reno, Georges Ribemont-Dessaignes, Jeanne Rij-Rousseau, André Dunoyer de Segonzac, Tobeen.

Delaunay’s 1911 painting rejects linear perspective and realistic shading, and embraces a Cubist-style dissection of forms — while also (unlike Picasso and Braque) deploying the fantastically vibrant colors of Orphism.

In Léger’s painting, the crowd lining the street take their fill of the bride. Broken lines, truncated forms, the arbitrary conjunction of realistic and unrealistic elements, and what has been called the “thoroughgoing mutation of the external and internal structure of the picture” owe much to Delaunay’s experimental canvases, “The City” (1911) and “The Windows” (1912).

Léger became a member of the Section d’Or group of artists.

Tea Time (Le Goûter) “was far more famous than any painting that Picasso and Braque had made up until this time”, according to Michael Taylor of the Philadelphia Museum of Art, “because Picasso and Braque, by not showing at the Salons, have actually removed themselves from the public… For most people, the idea of Cubism was actually associated with an artist like Metzinger, far more than Picasso.” the painting was exhibited in Paris at the Salon d’Automne of 1911, and also 1912’s Salon de la Section d’Or; it was reproduced in Du “Cubisme”, by Jean Metzinger and Albert Gleizes (1912); and in 1913 it was published in The Cubist Painters, Aesthetic Meditations by Apollinaire.

In his memoirs, Albert Gleizes writes of the structure of Tea Time:

The construction of his painting turns on the orchestration of these geometrical volumes, which shift their position, develop, interweave following the movements in space of the painter himself. Already we can see, as a consequence of this movement introduced into an art which, we were told, had no relation to movement, a plurality of perspective points. These architectural combinations of cubes supported the image as it appears to the senses, that of a woman whose torso is naked, holding in her left hand a cup while with the other hand she lifts a spoon to her lips. It can be easily understood that Metzinger is trying to master chance, he insists that each of the parts of his work must enter into a logical relationship with all the others. Each should, precisely, justify the other, the composition should be an organism as rigorous as possible and anything that looks accidental should be eliminated, or at least kept under control. None of that prevented either the expression of his temperament or the exercise of his imagination.

The painting was hailed as a breakthrough… “and opened the eyes of Juan Gris to the possibilities of mathematics”, writes John Richardson in A Life of Picasso (1996).

Tea Time was meant, according to A. Miller “as a representation of the fourth dimension. […] It is straight forward multiple viewing, as if the artist were moving around his subject.” (However, Du “Cubisme” written the following year does not mention the fourth dimension explicitly.)

“There is certainly a parallel to be drawn,” writes the art historian Peter Brooke in a letter to A. Miller, “between Einstein’s attempt to reconcile the different viewpoints from which mathematical calculations can be made (‘all reference points’) and the multiple perspective of the Cubists, attempting to establish what Metzinger called (in 1910) a ‘total image’.”

Yvonne and Magdeleine Torn in Tatters employs transparent, partly dematerialized forms overlapping one another. A study of modes of representation, drawing inspiration from x rays. See Linda Dalrymple Henderson.

Strikingly similar to Picasso’s Woman with a Guitar at the Piano (also 1911). The Cubists’ innovations included lettering, imitation wood grains, and the use of pasted paper — all of which emphasize by their literalness (or so critics tell us) the hallucinatory nature of the subject as a whole.

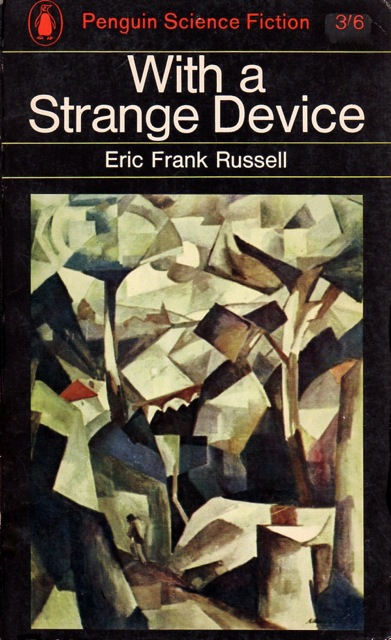

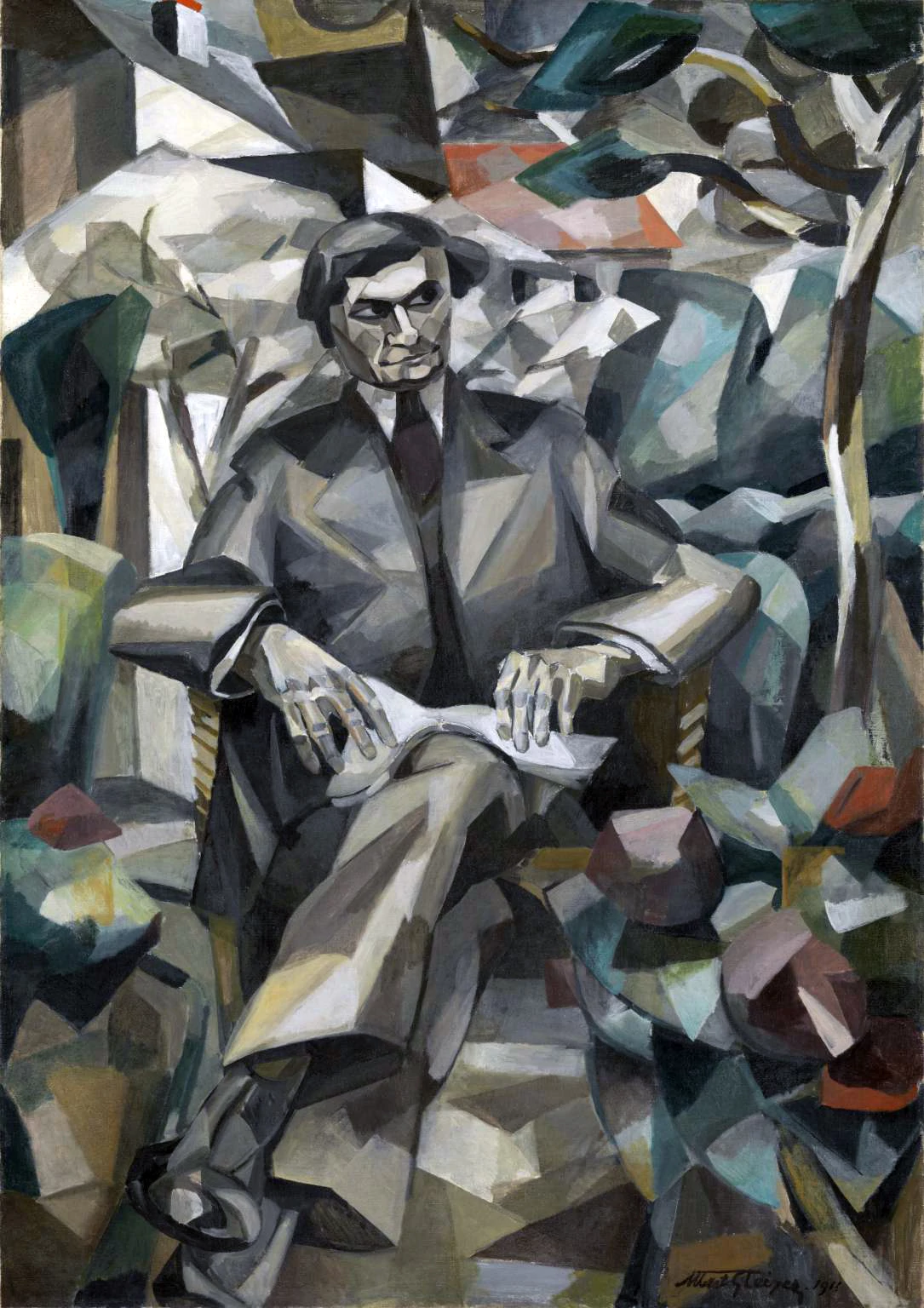

Gleizes’ painting was used to illustrate a 1965 Penguin edition of Eric Frank Russell’s sf novel With a Strange Device (also published under the title The Mindwarpers). See below.

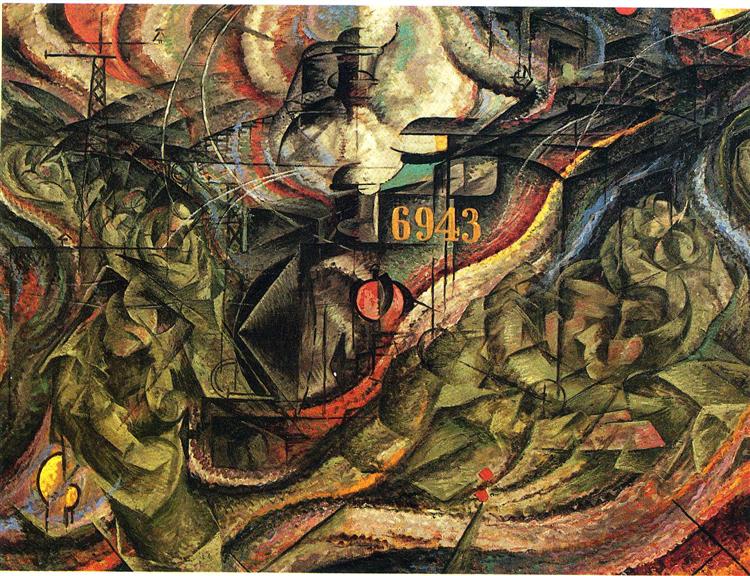

The website Utopia / Dystopia notes the following about this painting: “Boccioni took from Henri Bergson’s “theory of laughter” in his construction of The Laugh.” Bergson argued that laughter can relieve tension and break apart a person’s stiff mentality towards life. “The Cubist and Futurist movements both sought to restructure the foundations of society, getting people to rethink the bourgeois culture that had restricted humanity.” In aid of this sort of effort, Boccioni painted The Laugh, along with other works, to “create a scene that is broken apart and distinctly abstracted by a loss of structural borders.”

Having moved to Paris a few years earlier, for the Italian painter Gino Severini The Boulevard epitomizes the differences between what he described as “Futurism as conceived in Milan … and Futurism as conceived in Montmartre”.

A pivotal year for Mondrian, it was in 1911 that he viewed an exhibition at the Stedelijk Museum put on by the Moderne Kunstkring (a Circle of [Modern] Artists to which he belonged); it included the works of Cézanne, Picasso, and Braque — bringing Cubism to the Netherlands. Mondrian would relocate to Paris before the end of the year. While Picasso and Braque typically created portraits or still-lifes, Mondrian’s subject matter was nature, realized through a systematic network of right angles and grids. Additionally, his use of space was much flatter (and therefore less ambiguous, more schematic) than that of Cubism’s three (or four) dimensions.

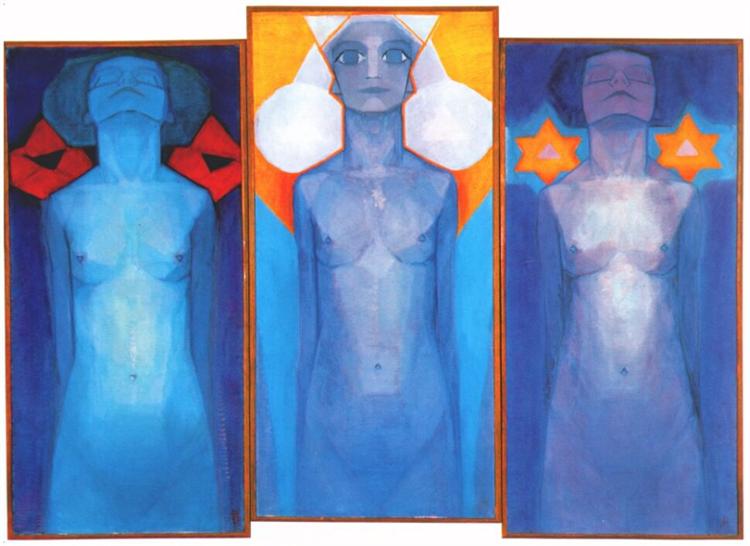

According to Robert Welsh’s “Mondrian and Theosophy” (in Regier, Kathleen J. (ed.), The Spiritual Image in Modern Art, Theosophical Publishing House, 1989), the blue and yellow colors used in Mondrian’s painting can be explained as astral “shells or radiations” of the figures.

It has been suggested that this painting depicts a single person undergoing spiritual initiation — first on the left (matter), then the right (soul), and finally to center figure (spirit). Which is why I’m putting into the SINGULARITY section, thought it is clearly also about UNSEEN FORCES. And even though we’ve heard that Mondrian didn’t paint portraits….

Although in the final version of Portrait of Chess Players the chess pieces are localized between the heads of the two brothers, in the preparatory drawings and the oil study Duchamp distributed the pieces more widely, including some within the heads of the two figures. These drawings suggest (claims Linda Dalrymple Henderson) that “a stimulus for Duchamp’s conception of the work may have been the numerous contemporary cartoons in which X rays of the heads of well-known individuals reveal objects symbolizing their character or interests.” The painting, then, is a mental portrait of these chess devotees.

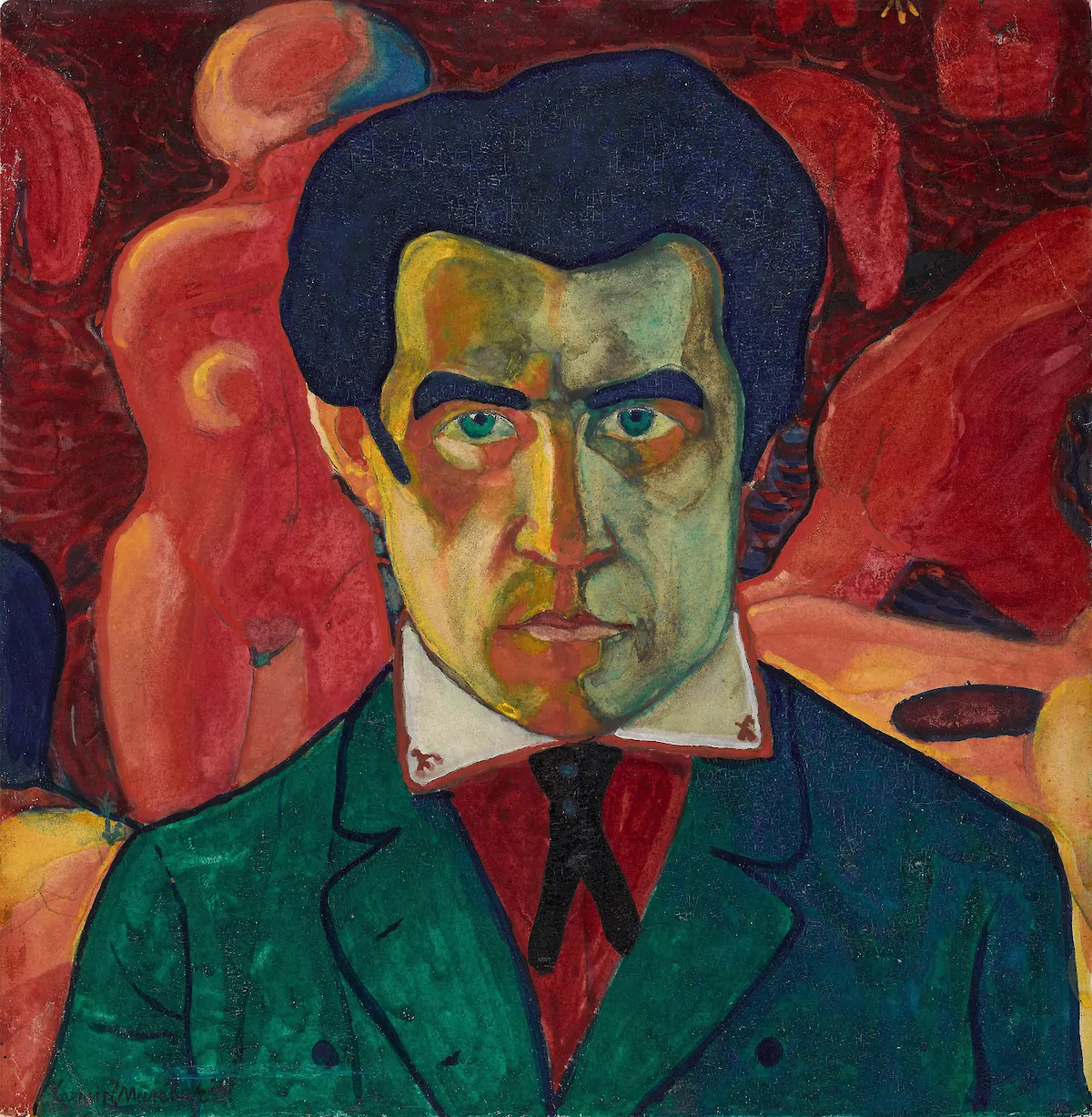

Hilton Kramer calls Kandinsky’s Composition V (1911) one of the most beautiful paintings that has ever been created in the name of abstraction.

NOTES ON DER BLAUE REITER

Der Blaue Reiter (The Blue Rider) is a designation by Wassily Kandinsky and Franz Marc for their exhibition and publication activities. They organized exhibitions in Munich in 1911 and 1912 to demonstrate their art-theoretical ideas based on the works of art exhibited. The group’s earliest members were Marc, Kandinsky, Klee, and August Macke. The Blue Rider would disband at the start of World War I.

In a succession of quasi-poetic statements, Marc would express the mystical and romantic elements undergirding the group’s ideas: Art is “the bridge into the spirit world… the necromancy of the human race.” The art to come, he prophesied, would be “the concretion in form of a scientific invention… It is deep and weighty enough to bring about the greatest re-shaping of form which the world has yet experienced.”

NOTES ON MONDRIAN

What motivated Mondrian towards abstract art was something more mystical than the impulse driving Picasso and Braque. In his own words, he aimed “to articulate a mystic conception of cosmic harmony that lay behind the surfaces of reality.” (He’d join Amsterdam’s Theosophical Society in 1909.) His theories of art were based on a system of opposites (cf. occultism, not to mention Saussure) such as male-female, light-dark, good-evil, positive-negative, dynamic-static, and mind-matter. These were represented in his work by right-angle lines and shapes as well as primary colors and black and white. The schematic system he created evoked the harmonious union of opposites.

The crossing-points in Mondrian’s mature work reflect the artist’s belief that the universe plays host to a constant conflict between opposing forces. They can be understood as a kind of semiosphere diagram, then.

NOTES ON THE SECTION D’OR

Members of the collective came to prominence in the wake of their showing at the Salon des Indépendants in the spring of 1911. This exhibit by Albert Gleizes, Jean Metzinger, Robert Delaunay, Henri le Fauconnier, Fernand Léger and Marie Laurencin created a scandal that brought Cubism to the attention of the general public for the first time.

The group seems to have adopted the name “Section d’Or” as both an homage to the mathematical harmony associated with Georges Seurat, and to distinguish themselves from the narrower style of Cubism developed in parallel by Picasso and Braque in Paris’s Montmartre quarter.

The idea of the Section d’Or originated in the course of conversations between Gleizes, Metzinger and Jacques Villon. The group’s title was suggested by Villon, after reading a 1910 translation of da Vinci’s A Treatise on Painting by Joséphin Péladan. Péladan attached great mystical significance to the “golden section” and other similar geometric configurations. For Villon, this symbolized his belief in order and the significance of mathematical proportions, because it reflected patterns and relationships occurring in nature. (Again, semiotics and modern art seem to spring from similar impulses.) Jean Metzinger and the Duchamp brothers were passionately interested in mathematics. Also: Jean Metzinger, Juan Gris and possibly Marcel Duchamp at this time were associates of Maurice Princet, an amateur mathematician credited for introducing profound and rational scientific arguments into Cubist discussions.

However, let’s not pretend these guys were mathematicians. As art historian David Cottington writes:

It will be remembered that Du “Cubisme”, written probably as these paintings were being made, gestured somewhat obscurely to non-Euclidean concepts, and Riemann’s theorems; as Linda Henderson has shown, these references betray not an informed understanding of modern mathematics but a shaky hold on some of their principles, culled (indeed plagiarized) from Henri Poincaré’s La Science et l’Hypothèse. The authors themselves had little clear idea of how such mathematics related to their art, except as a vague synecdoche for “modern science.”

MORE ON KANDINSKY’S “CONCERNING THE SPIRITUAL IN ART”

Kandinsky’s 1911/1912 book Über das Geistige in der Kunst would prove to be a seminal text in the history of modern art.

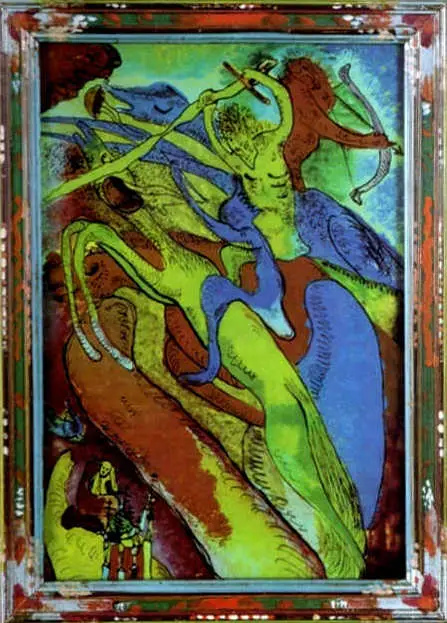

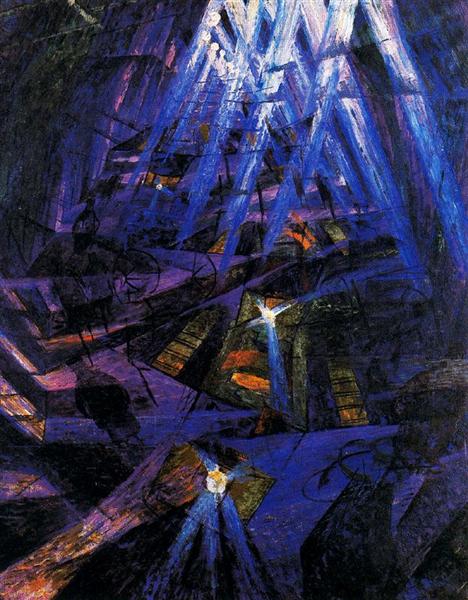

On the cover and in ten woodcuts, Kandinsky illustrated his ideas by reducing complex scenes of spiritual battle and redemption to simplified designs of lines and shapes. For Kandinsky, abstraction was a weapon for transforming what he perceived to be a corrupt, materialist society. The book lists several scientists whose work the artist finds inspiring; the late-19th century German astrophysicist and psychical researcher J.C.F. Zöllner, who helped popularize the concept of the Fourth Dimension, heads the list. Kandinsky suggests that Apollinaire’s earlier remarks about the Fourth Dimension are also likely inspired by Zöllner.

Zöllner had conducted dubious experiments in the late 1870s that seemed, he claimed, to verify occultists’ claims about a transcendental fourth dimensions.

From Theosophy, Kandinsky derives his concept that vibration is the formative agent behind all material shapes, which are but the manifestations of life concealed by matter. “Words, musical tones, and colors possess the psychical power of calling forth soul vibrations… ultimately bringing about the attainment of knowledge.”

Kandinsky here assesses two dangers for modernist art. The artist’s role is to depict spiritual truths — to get beneath realism and to express the sacred geometry of how things are. He worries that Matisse and Picasso, the artists then best known for defining the revolutionary developments in the visual arts throughout the opening decades of the twentieth century, were headed in bad directions. Matisse’s rigorous style (post-1906) emphasizing flattened forms and decorative patterns was the right idea, but… his exaggeration of color made his works merely ornamental, Kandinsky lamented. Picasso’s “destruction of the material object” was the right idea, meanwhile, but… instead of revealing an underlying truth, Picasso merely scattered the destroyed object’s pieces over the canvas — creating what Kandinsky dismissively named “fantasy.”

Shjeldal: “Kandinsky’s art has nothing important in common with Cubism, Futurism, or the other breakout movements of the epoch. His independence of Picasso made him a crucial influence on the efforts to blow open the knitted pictorial space of Parisian modernism — first of Joan Miró and later of Arshile Gorky and the Abstract Expressionists. The formal difference is apparent in Kandinsky’s shadings of fragmented shapes: they stay flat, rarely suggesting the outward and inward tilts, the bumps and hollows, of Cubism. Any illusion of internal space is usually an effect of the “push and pull” (a famous formulation by the artist and teacher Hans Hofmann) of cool and warm colors, or the front-and-back dynamic of linear designs overlaid on colored grounds.”

Again, two-dimensionality is more semiotic — because it suggests a schema, a chart, a graph of the artist’s elusive conceptual/spiritual subject.

ALSO…

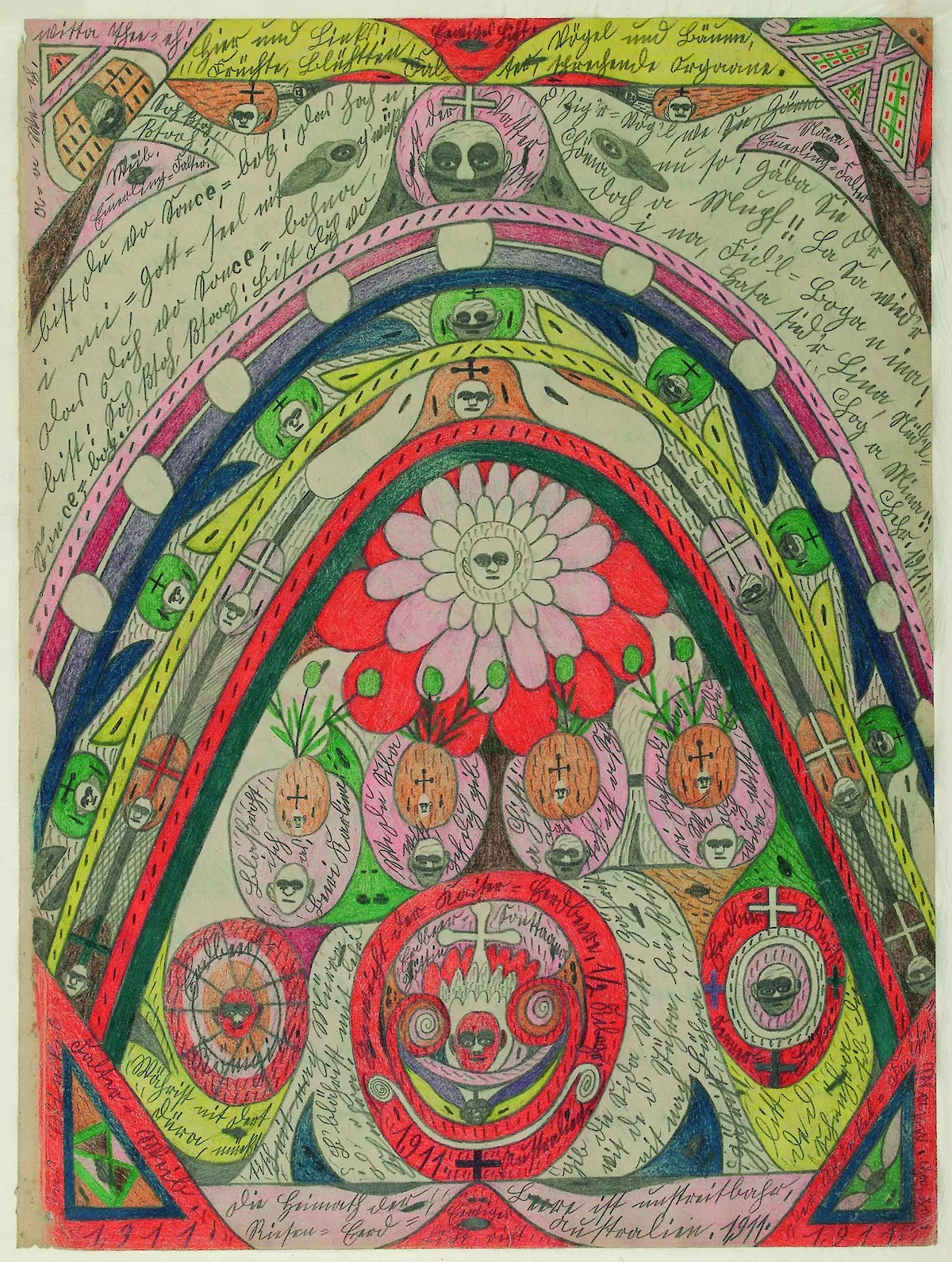

Amazing.

MORE RADIUM AGE SCI FI ON HILOBROW: RADIUM AGE SERIES from THE MIT PRESS: In-depth info on each book in the series; a sneak peek at what’s coming in the months ahead; the secret identity of the series’ advisory panel; and more. | RADIUM AGE: TIMELINE: Notes on proto-sf publications and related events from 1900–1935. | RADIUM AGE POETRY: Proto-sf and science-related poetry from 1900–1935. | RADIUM AGE 100: A list (now somewhat outdated) of Josh’s 100 favorite proto-sf novels from the genre’s emergent Radium Age | SISTERS OF THE RADIUM AGE: A resource compiled by Lisa Yaszek.