SEMIOPUNK (17)

By:

April 17, 2024

An irregular, ongoing series of posts dedicated to surfacing examples (and predecessors) of the sf subgenre that HILOBROW was the first to name “semiopunk.”

BABEL (2022) | BABEL-17 (1966) | CAMP CONCENTRATION (1968) | A CANTICLE FOR LEIBOWITZ (1959) | CAT’S CRADLE (1963) | COSMONAUT KEEP (2000) | THE DIFFERENT GIRL (2013) | DOOM PATROL (1987–91) | THE EINSTEIN INTERSECTION (1967) | EMBASSYTOWN (2011) | ENGINE SUMMER (1979) | EXPLOITS AND OPINIONS OF DR. FAUSTROLL, PATAPHYSICIAN (1911) | FEERSUM ENDJINN (1994) | FLATLAND (1884) | FRIDAY (1982) | LE GARAGE HERMÉTIQUE (1976–79) | THE GLASS BEAD GAME (1943) | GLASSHOUSE (2006) | GRAVITY’S RAINBOW (1973) | THE HAMPDENSHIRE WONDER (1911) | LORD OF LIGHT (1967) | THE MAN WITH SIX SENSES (1927) | THE MOUNTAIN IN THE SEA (2022) | NINEFOX GAMBIT (2016) | ODD JOHN (1935) | PATTERN RECOGNITION (2003) | THE PLAYER OF GAMES (1988) | RIDDLEY WALKER (1980) | RODERICK (1980–83) | SNOW CRASH (1992) | THE SOFT MACHINE (1961) | SOLARIS (1961) | THE SPACE MERCHANTS (1953) | THE THREE STIGMATA OF PALMER ELDRITCH (1964) | TIME OUT OF JOINT (1959) | UBIK (1969) | VALIS (1981) | A VOYAGE TO ARCTURUS (1920) | VURT (1993) | WHITE NOISE (1985).

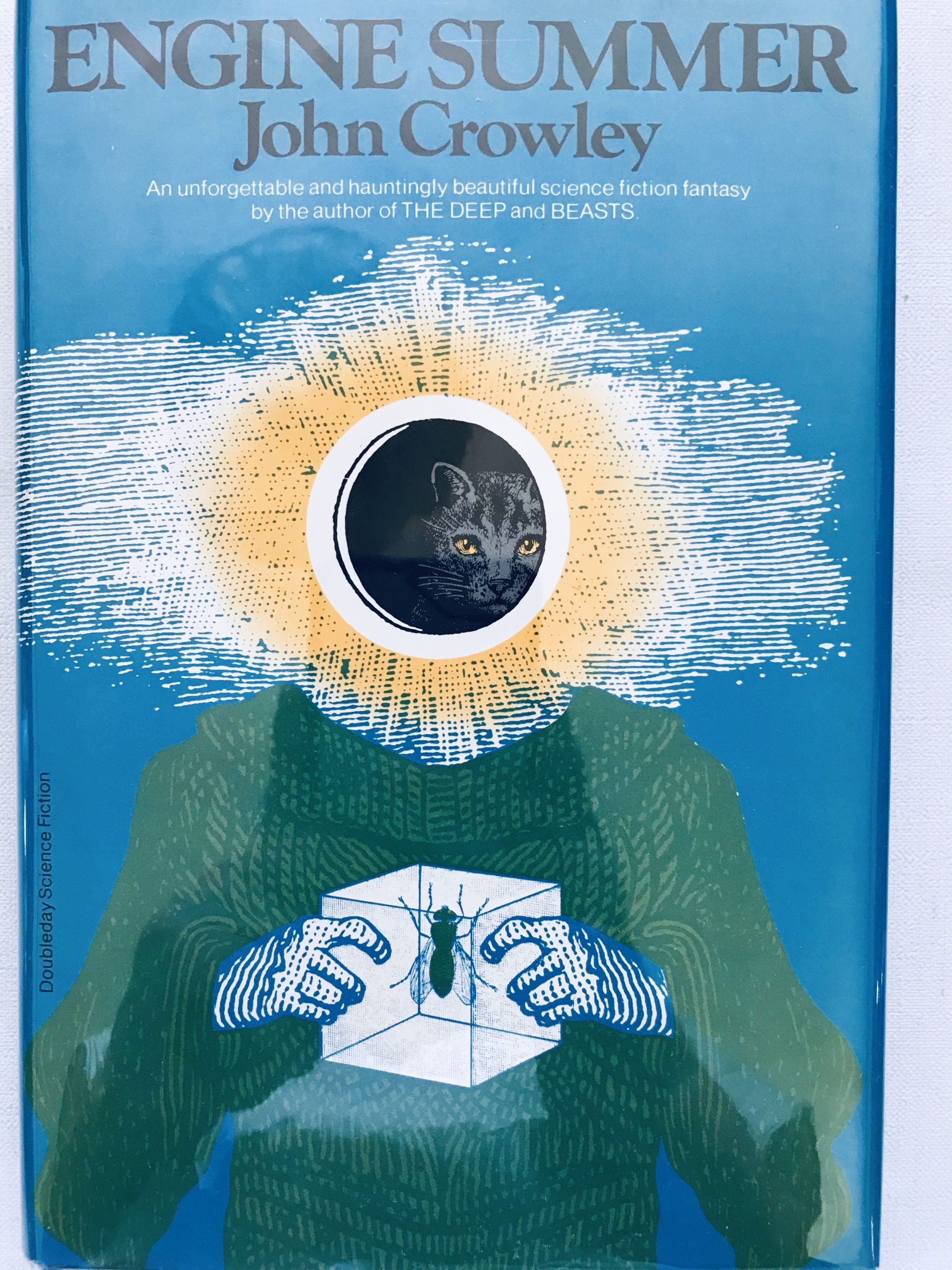

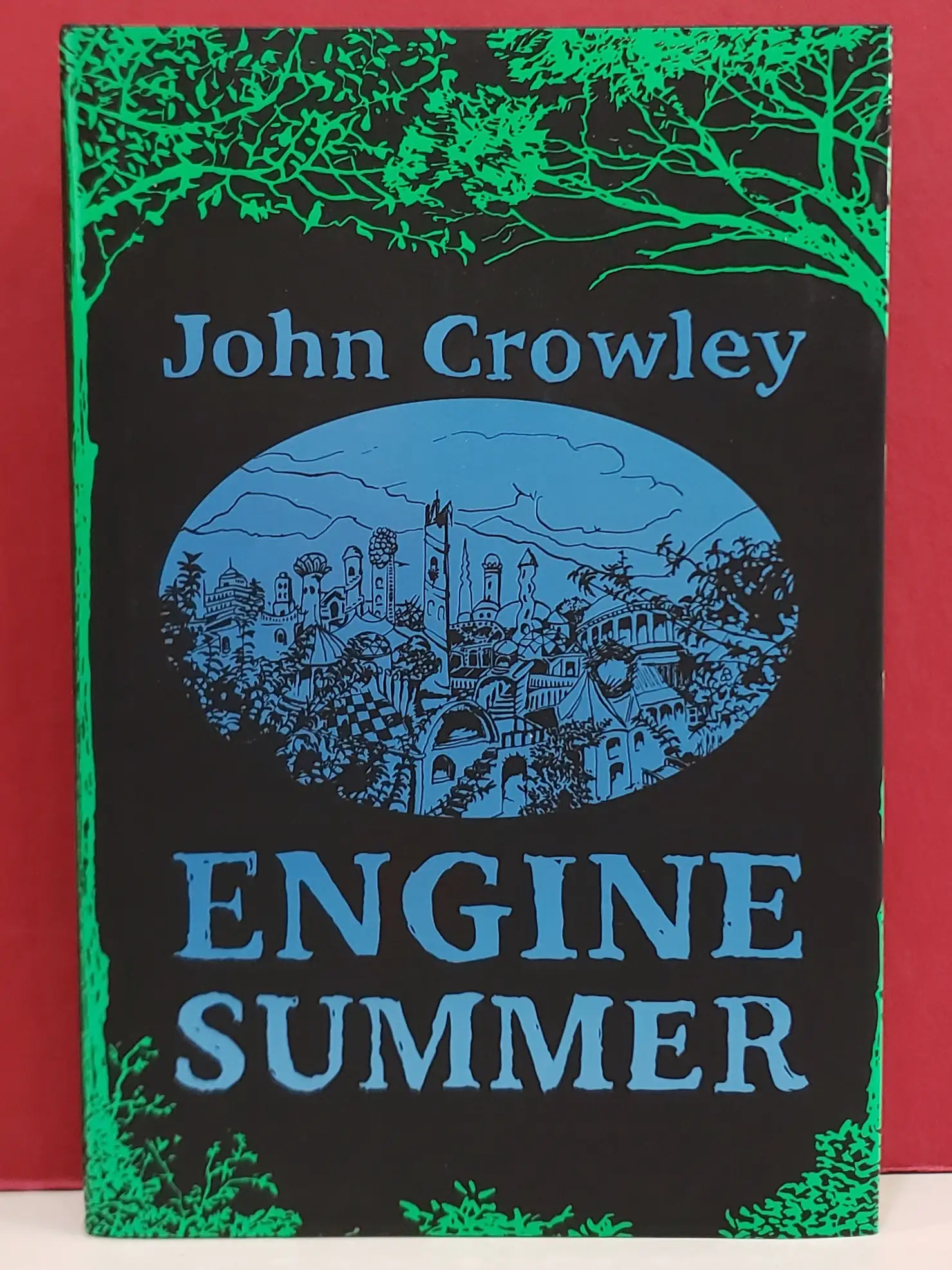

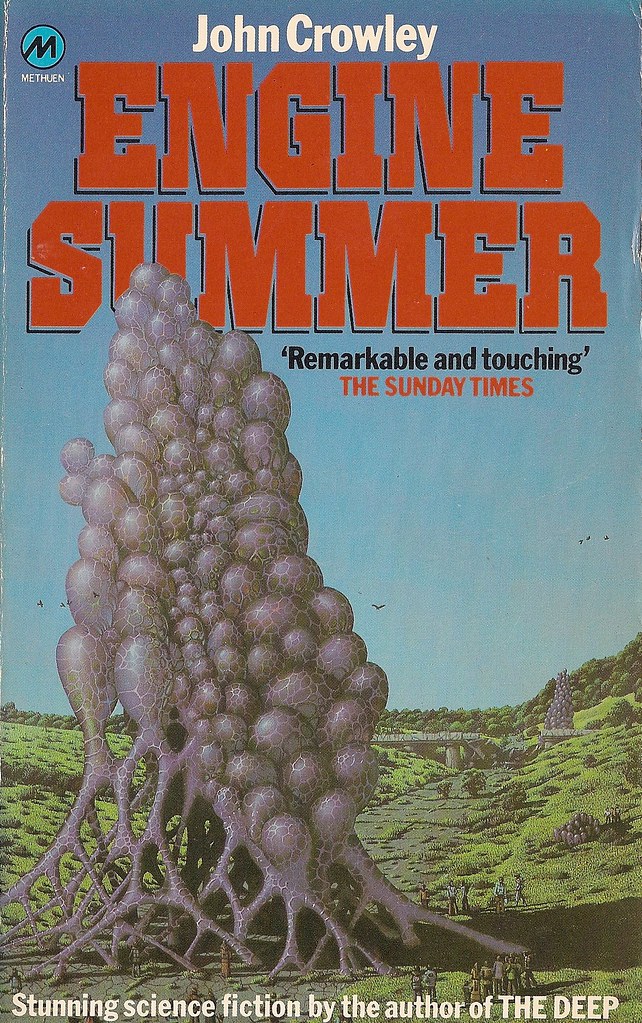

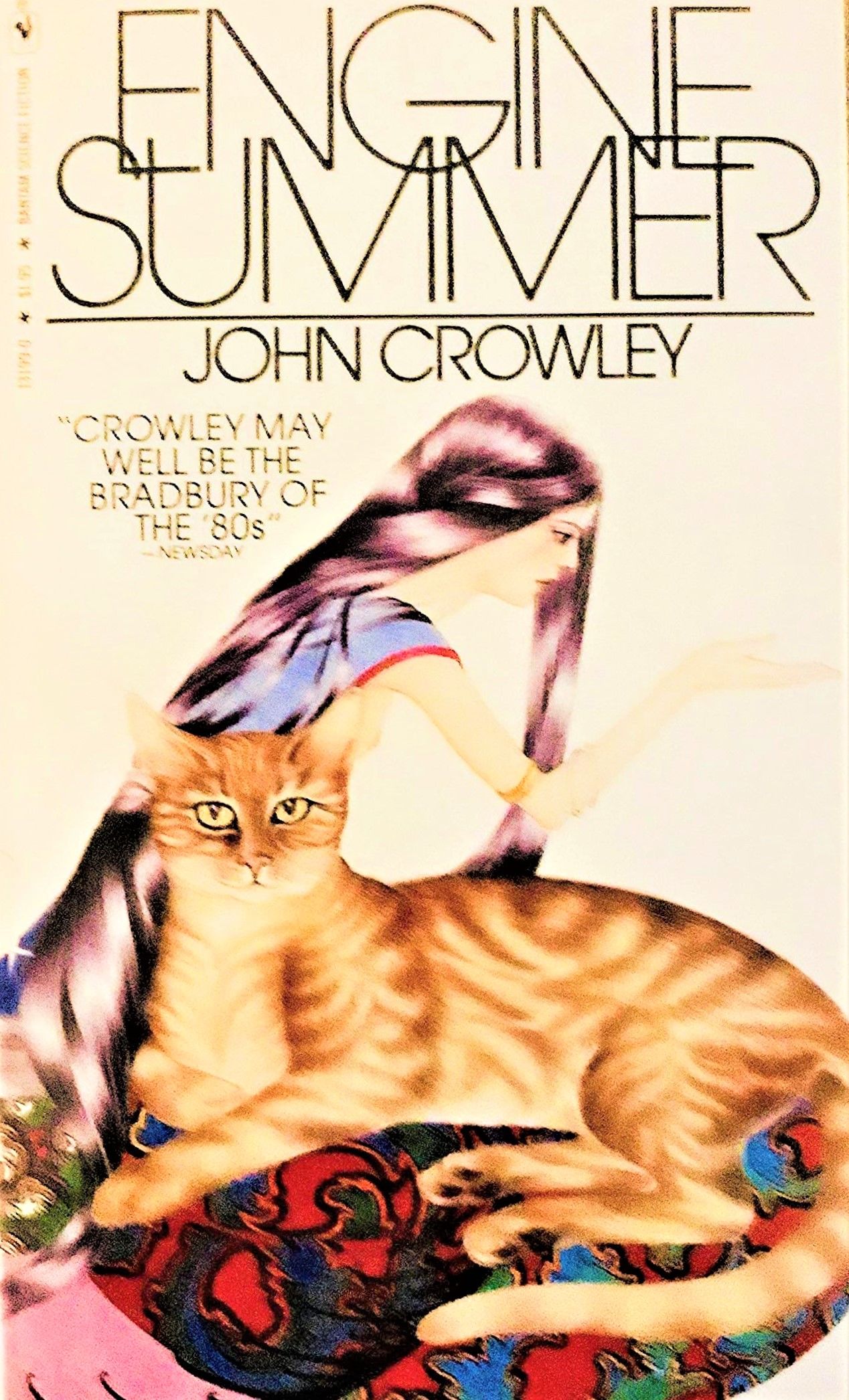

ENGINE SUMMER

When Rush That Speaks, the protagonist of John Crowley’s Engine Summer (1979), who has grown up in Little Belaire (a maze-like village of “truthful speakers,” the founders of which fled American society’s collapse), turns 14, he leaves home. His community calls someone with an important story to share a “saint”; they live not only in ages past, and he wants to be one too.

Rush That Speaks is also pursuing Once a Day, the girl he loves, who has run off with a Dr. Boot’s List, a nomadic group whom he’ll track to the ruins of Service City… and whose strangeness turns out to be a function of their annual use of an ancient technology that imposes a personality — from a mind-recording — temporarily over their own. Plus, he’s curious about the pre-catastrophe past, relics and rumors of which confound and amaze him. Like a semiotician who has spent too long brooding over disconnected fragments, he yearns to experience the “aha!” moment where all the dots finally connect up.

“When I was conceiving [Engine Summer],” Crowley has reminisced, “I thought I knew one thing about the future — that it was certain not to resemble our imaginings and projections. So I discarded all the things that looked likely, based on current trends: technological advances, overpopulation, international networks of trade and competition, advanced weaponry. I erased cities, governments, even literacy, and yet I imagined that out of the unlikeliest bits of the present, new spiritual trends could arise, and a new language in which to express them.” This is the opposite of how science fiction — “hard” science fiction, anyway — usually works, and I’m here for it. It’s defamiliarizing… a story about a future in which everyone is obsessed with hearing stories about the past — our present.

Engine Summer opens with our narrator in conversation with another person, an “angel.” He denies that he was asleep — he has only closed his eyes. He opens them to find himself “above the clouds, below the sky” — what could this mean? The angel asks him for his story. It appears that Rush That Speaks has indeed become a “saint” — one with whose stories people are fascinated. This framing device, some readers may discern, is not unconnected to the “mind-print” device employed by Dr. Boot’s List. The patterns of one person’s mind can be superimposed on one’s own… which leads to an addictive rush of returning self-knowledge as the effect wears off.

A thriller this isn’t. It’s quiet, slow-moving, richly detailed… and then suddenly, at the end, all finally becomes more or less clear. One could describe Crowley’s fantasy masterpiece, Little, Big (1981) the same way. Both books will leave you stunned.

Little Belaire is a richly imagined community, one that we’re sorry to see our protagonist leave behind. They harvest and sell a psychotropic fungus, it seems, the origin of which is not Earthly. Their people survived the catastrophe (the “Storm”) thanks to a pre-catastrophe cabal of radical feminists, maybe, who purposely eradicated from their ancestors’ practices and memory all vestiges of technology and “male” (utilitarian, hierarchical) thinking. However, some vestige of the highly technological pre-catastrophe civilization may still exist… floating in cities above the clouds: the “angels.”

The founders of Little Belaire appear to have been into Gurdjieff-esque psycho-spiritual theories of interconnected personality types. Their community’s inhabitants are categorized into “cords” consisting of certain personality baselines; when consulted, “gossips” consult a “filing system” before offering advice. The “Whisper” cord to which Once a Day belonged seem to know more about the big picture than the members of other cords. Whereas Truthful Speakers are expert in reading one’s disposition and revealing one’s own disposition, the Whisper folks are elusive and allusive. Perhaps this is what Rush That Speaks finds so alluring about Once a Day — who does not reciprocate.

Having set out from Little Belaire — which seems to be in New England, or possibly upstate New York — Rush That Speaks spends some time living with Blink, a saint and scavenger who has learned a few things about the advanced but unhappy prelapsarian world. Through Blink, Rush That Speaks finds a high-tech whistling ball and glove — two linked artifacts that have been separated for centuries. By bringing them together, our protagonist sets into motion the actions that will bring an end to his story… and to life as he’s known it.

“When you are putting things together in this way and you have a character who is trying to ponder the bits and pieces he’s found or discovered,” Crowley once mused in another interview, “what that character — if he’s a thinker, as many of the characters I write tend to be heavy thinkers, hard thinkers anyway — would think about is, How am I putting this together? Is this an actual thing I’m putting together, or am I fooling myself? Is it totally lost and am I creating a new thing out of what I found, or am I actually finding a way back to a lost world? I think that’s what we do in our daily lives, a lot of the time, even when we try to construct our own past.”

Crowley describes here the semiotician’s central dilemma. Are the structural schemas we painstakingly puzzle out and construct accurate representations of the way meaning works within a particular “semiosphere”? Or are we apophenically hallucinating?

Originally written in the Sixties, then rewritten for publication a decade later, Engine Summer is in some ways an elegy for the Sixties — a time when the “actual thing” seemed imminently available to curious, well-meaning, gentle-souled seekers. Some of whom joined Dr. Boot’s List-ish communities and some of whom (like Rush Who Speaks, who upon locating Once a Day wants to experience the mind-pattern thing) were damaged irrevocably in the process.

The book’s ending is a deeply poignant one.

Crowley is best known, I think, as the author of Little, Big and for his Ægypt series of novels (1987–2007). I like these books, too, but strongly urge sf fans to revisit his sf work. In addition to this book: The Deep (1975), the narrator of which is a damaged android; Beasts (1976), which features genetically engineered animal/human hybrids; and Great Work of Time (1989/1991), which warns of the consequences of attempting to control history via time travel.

JOSH GLENN’S *BEST ADVENTURES* LISTS: BEST 250 ADVENTURES OF THE 20TH CENTURY | 100 BEST OUGHTS ADVENTURES | 100 BEST RADIUM AGE (PROTO-)SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST TEENS ADVENTURES | 100 BEST TWENTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST THIRTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST GOLDEN AGE SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST FORTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST FIFTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST SIXTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST NEW WAVE SCI FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST SEVENTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST EIGHTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST DIAMOND AGE SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST NINETIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST HADRON AGE SCI-FI ADVENTURES.