FIRST TIME AS COMEDY (5)

By:

April 13, 2024

Some years ago, HILOBROW friend Greg Rowland pointed out that the 1990 movie Dances With Wolves ought to be regarded as a sentimental remake of the 1970 revisionist Western Little Big Man. The series FIRST TIME AS COMEDY will offer additional examples of this recursive (and often, though not always middlebrow) syndrome.

FIRST TIME AS COMEDY: SUPERDUPERMAN vs. WATCHMEN | WILD IN THE STREETS vs. PREZ | EMIL AND THE DETECTIVES vs. M | THE SAVAGE GENTLEMAN vs. DOC SAVAGE | GULLIVAR JONES vs. JOHN CARTER | THE PHONOGRAPHIC APARTMENT vs. HAL | HIGH RISE vs. OATH OF FEALTY | JOHNNY FEDORA vs. JAMES BOND | MA PARKER vs. MA BARKER | DARK STAR vs. ALIEN | SHOCK TREATMENT vs. THE TRUMAN SHOW | JOHNNY BRAVO vs. ROCK STAR | THE FUTUROLOGICAL CONGRESS vs. THE MATRIX | CAVEMAN vs. SASQUATCH SUNSET | LITTLE BIG MAN vs. DANCES WITH WOLVES | THE LAST BLACK MAN IN SAN FRANCISCO vs. BE KIND REWIND | LEN DEIGHTON vs. LEN DEIGHTON.

Edwin Lester Arnold published the travelogues A Holiday In Scandinavia (1877), and Bird Life In England (1887) before writing a popular novel The Wonderful Adventures of Phra the Phoenician (1890), the adventures of a warrior who goes in and out of an unexplained state of suspended animation in order to witness various historical invasions of England. Subsequent novels, including Rutherford the Twice-Born (1892) and Lepidus the Centurion: A Roman of Today (1901), were flops.

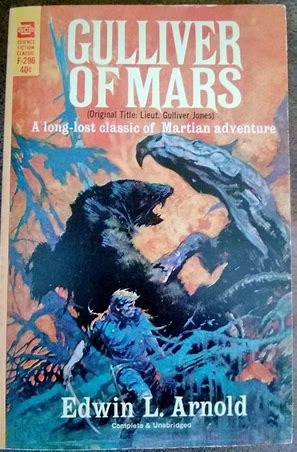

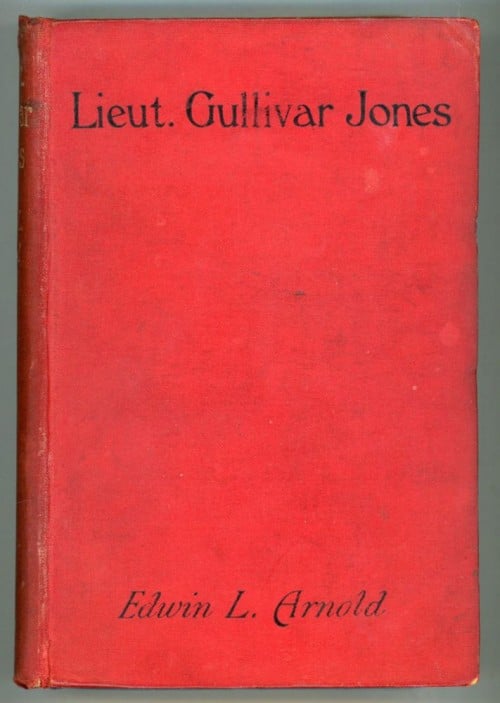

He then published Lieut. Gullivar Jones: His Vacation (1905), a proto-sf (science fantasy, really) work in which a military man from the Southern United States arrives semi-miraculously on Mars, where he has numerous adventures, including falling in love with a Martian princess. Sound familiar? Alas, the novel’s lukewarm reception led Arnold to stop writing fiction.

A satirical, nightmarish, episodic update of Gulliver’s Travels, Lieut. Gullivar Jones transports an arrogant US Naval officer to Mars (a jungle planet, not a desert planet) via magic carpet. Here, he gains super strength and telepathic powers, and proceeds to stumble into and out of trouble.

There is a war brewing between the beautiful, innocent, sophisticated Hither Folk and the barbaric, industrious Thither Folk; Gullivar tries but fails to prevent the war. He also attempts to claim a vast tract of Mars for himself, travels down a river of death, fails to outwit or defeat his enemies, and fails to win the hand of the beautiful Princess Heru. (Oh, and there is a flying city: Laputa.) Inadvertently escaping back to Earth, finally, Gullivar reunites with his estranged fiancée and is married the following week.

As with much proto-sf from the Radium Age, H.G. Wells is being tweaked here. The graceful and elegant Hither Folk are sensual, even sexual, free of all cares and utterly slothful. Their society is one in decay, the knowledge which built their soaring cities long forgotten, their economy based on the labor of passive slaves. Unlike Wells’s childlike Eloi, whose society we find charming, the Hither folk are repulsive. One wonders if E. M. Forster’s “The Machine Stops” (1909) was influenced by Arnold’s satirical take on leisurely future utopias?

Wells’s brutish, repulsive Morlocks (also from his 1895 novel The Time Machine), who dwell underground maintaining ancient machines, are likely descendants of the English working class. Arnold’s Thither Folk, meanwhile, though barbarous and violent, are as individuals honorable, industrious — even noble in a way. Which makes me think of Iain M. Banks’s first Culture novel Consider Phlebas (1987), the protagonist of which — Bora Horza Gobuchul — is an honorable, principled agent of the barbarous and violent Iradans — enemies of the post-scarcity, utopian Culture.

Arnold’s Gullivar, meanwhile is an “ugly American” abroad. He is supremely arrogant, condescending and racist towards his hosts (Hither or Thither), and when claims a vast swath of Mars for the United States, he uses a satirical version of the Monroe Doctrine as justification: “Oh, it is simple enough, and put into plain language means you must not touch anything that is mine, but ought to let me share anything you have of your own.” Unlike the author’s macho, atavistic character Phra the Phoenician, Gullivar is fairly wimpy.

In a post from 2020, the website Balladeer’s Blog finds Arnold’s story disappointing.

If Arnold had written this story decades later it could have been said that he was intentionally subverting the tropes of heroic sword & science epics. Unfortunately, this novel instead seems to be the victim of ineptitude on the author’s part. Like when you’re watching a bad movie, a reader’s jaw drops at the way Arnold never failed to let a brilliant concept die on the vine, or the way he repeatedly sets up potentially action-packed or highly dramatic story developments only to let them culminate in unsatisfying cul de sacs or peter out into lame anticlimax. There’s almost a perverse genius to the way that the narrative constantly works against itself.

Yes, this is the uncanny aspect of the First Time as Comedy syndrome. Earlier works that fail to provide satisfyingly escapist thrills, chills, and justly deserved rewards, come to seem like satirical take-downs of later works that do provide these things!

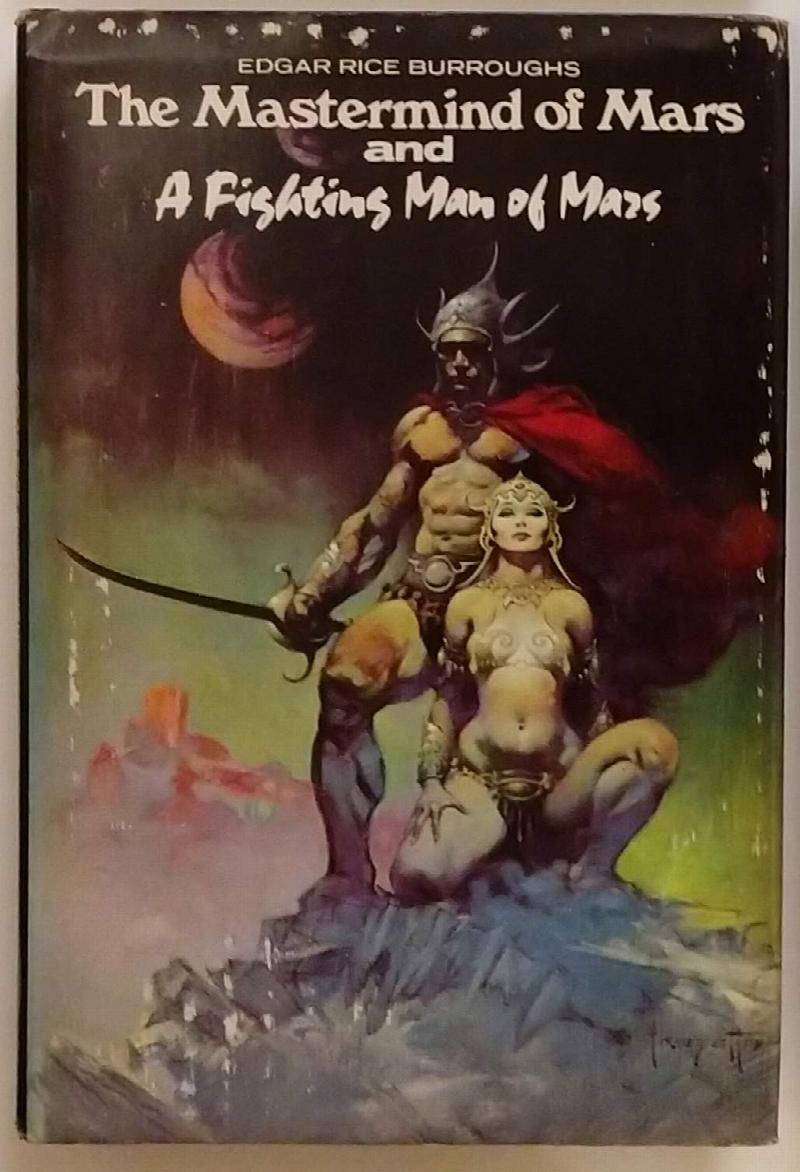

By “heroic sword & science epics,” Balladeer’s Blog is referring, of course, to science fiction’s Planetary Romance * subgenre — most notably, Edgar Rice Burroughs’s Barsoom series — adventure tales set on a primitive planet, Mars (Barsoom). Other important contributors to the form from the Radium Age include Ralph Milne Farley, Homer Eon Flint and Otis Adelbert Kline. Robert E. Howard’s Almuric (May-August 1939 Weird Tales) carries this sort of thing forward into sf’s so-called Golden Age era.

* From the Science Fiction Encylopedia, we learn that in his introduction to a 1978 reprint of Philip José Farmer’s The Green Odyssey (1957) Russell Letson argues strongly for the use of the term “planetary romance” to describe novels whose basic settings derive from Burroughs, whose plots often make use of the chase-and-quest conventions of adventure fiction, and whose protagonists frequently turn out to be high-tech men or women “stranded among pretechnological natives.”

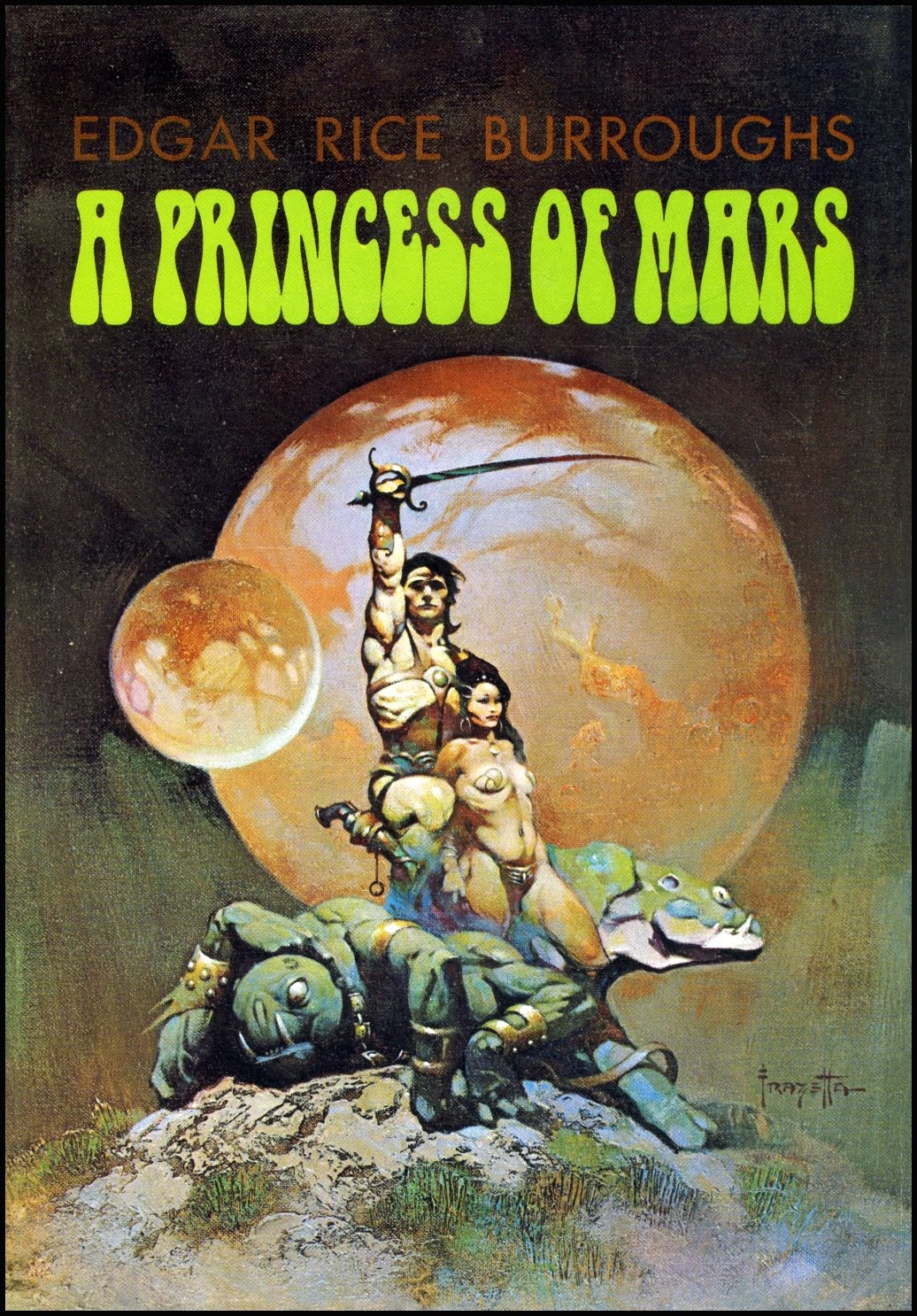

So yes, let’s consider now Burroughs’s Barsoom adventures. A Princess of Mars (February-July 1912 All-Story as “Under the Moons of Mars” as by Norman Bean; 1917 in book form) opens the long Barsoom sequence of novels set on Mars (Barsoom). Transported to Mars — via something like astral projection — ex-soldier John Carter finds himself embroiled in a war between the Red and Green Martians. The barbaric, nomadic Green Martians are 15 feet tall, with six limbs; they inhabit the abandoned cities of Barsoom. The Red Martians, meanwhile, are civilized humanoids, organized into city-states that control Barsoom’s water.

Carter’s unusual coloring, and the extraordinary strength he is afforded by the planet’s weak gravity, make him uniquely capable of forming alliances among honorable members of both Barsoomian peoples. He falls in love with Dejah Thoris, beautiful daughter of a Red Martian chieftain, and rescues her from both Green and Red Martians before leading a Green Martian army against the enemy of Thoris’s state.

The Gods of Mars (January-May 1913 All-Story; 1918) and The Warlord of Mars (December 1913-March 1914 All-Story; 1919), and many other installments further recount the exploits of John Carter as he encounters and battles various Martian races, and wins the hand of princess Dejah Thoris. Oh, and there is also a journey down a river of death.

The concept of a military man going to Mars, exploring strange civilizations and falling in love with a princess had been explored as far back as Percy Greg’s 1880 Across the Zodiac. (PS: This book is notable for containing what seems to be the first alien language in any work of fiction to be described with linguistic and grammatical terminology. What’s more, it contains what is possibly the first instance in the English language of the word Astronaut, which features as the name of the narrator’s spacecraft.) But no further textual evidence is required for us to decide, as many others already have, that Burroughs very likely borrowed the setting and plot of his first Barsoom installments from Arnold’s Lieut. Gullivar Jones; the macho, atavistic John Carter, meanwhile, appears to ape Arnold’s Phra the Phoenician.

Unlike Arnold’s Gullivar, of course, Burroughs’s Carter succeeds at everything to which he turns his hand. The reader’s fondest wishes are fulfilled. Unlike Arnold, who never wrote again after the failure of his satire, Burroughs became the most successful pulp writer ever.

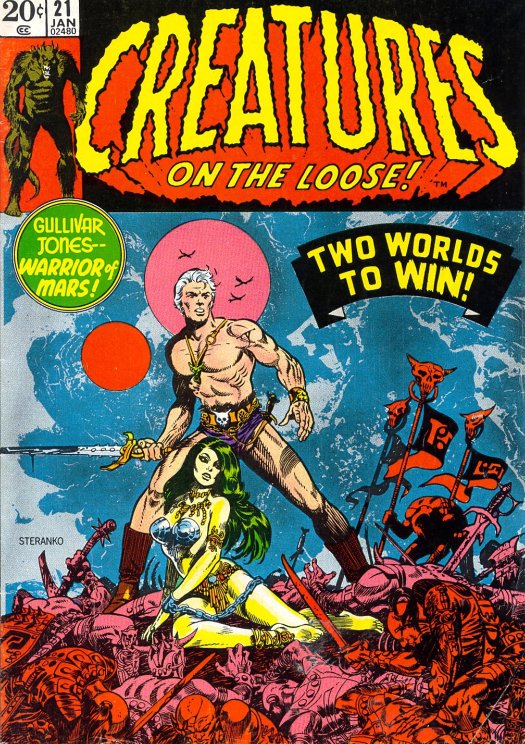

PS: Here’s a further twist in this Moebius strip. Marvel Comics adapted Arnold’s character for the comic book feature “Gullivar Jones, Warrior of Mars” in Creatures on the Loose #16–21 (March 1972 – January 1973). Here we find a Jim Steranko cover depicting a Gullivar / John Carter mashup — striking a Frazetta-style pose. Freaky!

MORE FURSHLUGGINER THEORIES BY JOSH GLENN: SCHEMATIZING | IN CAHOOTS | JOSH’S MIDJOURNEY | POPSZTÁR SAMIZDAT | VIRUS VIGILANTE | TAKING THE MICKEY | WE ARE IRON MAN | AND WE LIVED BENEATH THE WAVES | IS IT A CHAMBER POT? | I’D LIKE TO FORCE THE WORLD TO SING | THE ARGONAUT FOLLY | THE PERFECT FLANEUR | THE TWENTIETH DAY OF JANUARY | THE REAL THING | THE YHWH VIRUS | THE SWEETEST HANGOVER | THE ORIGINAL STOOGE | BACK TO UTOPIA | FAKE AUTHENTICITY | CAMP, KITSCH & CHEESE | THE UNCLE HYPOTHESIS | MEET THE SEMIONAUTS | THE ABDUCTIVE METHOD | ORIGIN OF THE POGO | THE BLACK IRON PRISON | BLUE KRISHMA | BIG MAL LIVES | SCHMOOZITSU | YOU DOWN WITH VCP? | CALVIN PEEING MEME | DANIEL CLOWES: AGAINST GROOVY | DEBATING IN A VACUUM | PLUPERFECT PDA | SHOCKING BLOCKING.