SEMIOPUNK (15)

By:

March 15, 2024

An irregular, ongoing series of posts dedicated to surfacing examples (and predecessors) of the sf subgenre that HILOBROW was the first to name “semiopunk.”

BABEL (2022) | BABEL-17 (1966) | CAMP CONCENTRATION (1968) | A CANTICLE FOR LEIBOWITZ (1959) | CAT’S CRADLE (1963) | COSMONAUT KEEP (2000) | THE DIFFERENT GIRL (2013) | DOOM PATROL (1987–91) | THE EINSTEIN INTERSECTION (1967) | EMBASSYTOWN (2011) | ENGINE SUMMER (1979) | EXPLOITS AND OPINIONS OF DR. FAUSTROLL, PATAPHYSICIAN (1911) | FEERSUM ENDJINN (1994) | FLATLAND (1884) | FRIDAY (1982) | LE GARAGE HERMÉTIQUE (1976–79) | THE GLASS BEAD GAME (1943) | GLASSHOUSE (2006) | GRAVITY’S RAINBOW (1973) | THE HAMPDENSHIRE WONDER (1911) | LORD OF LIGHT (1967) | THE MAN WITH SIX SENSES (1927) | THE MOUNTAIN IN THE SEA (2022) | NINEFOX GAMBIT (2016) | ODD JOHN (1935) | PATTERN RECOGNITION (2003) | THE PLAYER OF GAMES (1988) | RIDDLEY WALKER (1980) | RODERICK (1980–83) | SNOW CRASH (1992) | THE SOFT MACHINE (1961) | SOLARIS (1961) | THE SPACE MERCHANTS (1953) | THE THREE STIGMATA OF PALMER ELDRITCH (1964) | TIME OUT OF JOINT (1959) | UBIK (1969) | VALIS (1981) | A VOYAGE TO ARCTURUS (1920) | VURT (1993) | WHITE NOISE (1985).

BABEL-17

In Samuel R. Delany’s short, semiotics-inspired space opera — released by the pulp sf publisher Ace Books in 1966, it would share a Nebula Award with Flowers for Algernon, while losing out to Dune for a Hugo — humanity has spread itself throughout the galaxy. Now humankinds’ Alliance is at war with an alien culture, the so-called Invaders, who are up to something — what? — that seems potentially catastrophic.

The action begins in media res. Starship captain and celebrity poet (!) Rydra Wong has already determined that Babel-17, an impenetrable code used to cue Invader terrorist attacks all over the Alliance, is in fact a language. As Rydra, who is also something of a linguistics / semiotics expert, puts it: It’s an independent pattern of symbols with “its own internal logic, its own grammar, its own way of putting thoughts together with words that span various spectra of meaning.” Babel-17 is a semiosphere, if you will. Full comprehension of Babel-17 isn’t merely a matter of cracking a code, then; it requires understanding of Babel-17’s gestalt: Who is speaking it, to whom, and to what end?

In pursuit of answers to such questions, Rydra pulls together a starship team and sets off for space. But wait, not so fast! It turns out that Alliance starships have very specific crew requirements. They need to be staffed not only by genetically modified polyamorous trios, but by the consciousnesses of the “discorporate,” which is to say the deceased: literally, a ghost in the machine. So a substantial section of the novel is devoted to Rydra’s scouring the East Village-like bohemia inhabited by bio-modding, sexually fluid “Transport” workers — a bohemia looked down on by the non-bohemian types who work in “Customs.”

One is reminded of semioticians and their clients; they need us, but also find us weird and other. In fact, one subplot involves a Customs Officer, a straight and strait-laced white male, losing his resistance to the polymorphous-perverse appeal of the “Transport” demimonde.

Most of the consulting semioticians of my acquaintance work alone, in fact. In order to do so, we must oscillate rapidly between modes of knowledge-acquisition and -formulation: inductive, deductive, abductive; beginner’s mind and expert. In an unfinished piece of fiction I wrote in 2020, I imagined a semiotics agency the members of which were more highly specialized: “inductives,” “deductives,” “abductives.” The crack team who meets to map out the codes of a particular pop-culture franchise call themselves, half-jokingly, the “Abduction Squad.” This isn’t really the situation in Babel-17, though; Rydra needs her crew to help her pilot the spaceship, not figure out Babel-17.

Babel-17 is an adventure yarn — a space opera, as noted — in which one will find everything from hand-to-hand combat to full-scale spaceship battles. But the real adventure is one of ratiocination — Rydra’s puzzling over Babel-17.

Like subsequent sf authors, including Neal Stephenson and Ted Chiang, Delany depicts language as absolutely determining thought and experience. He is playing out the dramatic implications of the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis — the idea of linguistic relativity, first floated by Sapir in 1929 (during sf’s Radium Age). The structure of a language determines a native speaker’s perception and categorization of experience; the language you speak constrains what you can know, believe, and even perceive.

As she learns to speak and think in Babel-17, as she spelunks this alien semiosphere, Rydra discovers that her perceptions and thoughts are altered. Babel-17 is a language of dense precision; each word opens up into a vast idea-complex. Rydra — already something of a telepath — finds her cognitive abilities altering and evolving, making her almost superhuman. She can perceive reality as a concatenation of fine-grained patterns; this is a semiotician’s dream, of course.

There’s a downside to Babel-17, too. Rydra falls in love with the Butcher, an amnesiac violent convict (and former Alliance super-soldier) whose Babel-17-shaped speech is bereft of the words “I” or “you.” Without concepts of personhood and relation, the Butcher is amoral. Babel-17 is a machine language, intended for machines with no sense of self — and therefore no compassion. Rydra empathetically attempts to teach the Butcher these personhood concepts…

“Are they the same word for the same thing, that they are interchangeable?”

“No, just… yes! They both mean the same sort of thing. In a way, they’re the same.”

“Then you and I are the same.”

Risking confusion, she nodded.

“I suspect it. But you—” he pointed to her — “have taught me.” He touched himself.

“And that’s why you can’t go around killing people. At least you better do a hell of a lot of thinking before you do.”

But this sentimental education is a two-way street, Rydra discovers.

Speaking of Rydra’s empathy, in an essay for HILOBROW’s sister site, SEMIOVOX, Ramona Lyons makes this incisive point:

It’s genius — and exciting to see science fiction and sociolinguistic theory cross streams this way, and in such a virtuoso form. But, celebrating this conceit alone misses the point of the book, and what I know to be true about the practice of decoding. According to Babel-17, decoding requires not just intelligence, but intuition and empathy. […] Despite all her other gifts, Rydra’s true superpower is openness to her own feelings whenever she encounters another piece of the puzzle.

This is something that you can’t learn in school, of course.

As mentioned, there’s a downside to Rydra’s capacity for empathy and intuition. She begins to turn against the Alliance. To become machine-like….

The novel ends with the promise that Rydra and the Butcher can bring galactic peace by endowing Babel-17’s cognitive power with their own moral energy, their insistence that “I” and “you” matter. But it’s just a promise….

Babel-17 is full of semiotic insights like this one: “An individual, a thing apart from its environment, and apart from the things in that environment; an individual was a type of thing for which symbols were inadequate, and so names were invented.”

This stuff is over my head, but I find it persuasive.

Why isn’t Babel-17 a more beloved, and widely read book? In a 1980 essay, “Semiotics, Space Opera and Babel-17,” William H. Hardesty III suggests that it’s too much of a hybrid: “On the one hand, Babel-17 is a serious novel speculating about future developments in certain technologies related to one another; on the other hand, it is an outrageous space opera.”

In the context of the 1960s, space opera had not yet been “redeemed.” It was seen by highbrow sf fans as an embarrassing remnant of the genre’s awkward adolescent period. E.E. “Doc” Smith (who helped popularize space opera during the Radium Age, and continued into the sf genre’s so-called Golden Age); Jack Williamson’s Legion of Space; Leigh Brackett’s oeuvre. It was Delany — and Frank Herbert, whose Dune won the Hugo instead of Babel-17 — who reintroduced space opera during the era’s New Wave period. In 1980, Alejandro Jodorowsky and Jean Giraud — under the influence of Delany and Herbert alike — helped make space opera popular for wised-up sf fans. Iain M. Banks would build on this foundation….

Hardesty makes a good point about Delany’s engagement with the space-opera medium:

Delany’s use of space-opera elements begins to make sense. The elements of space opera constitute a system of signs — an imagery analogous to the poetic imagery used by Rydra herself. The writer of a space opera is communicating on several levels, including one of emotional responses to the stock situations and characters. The message conveyed at this level is reassuring: the reader is being told (among other things) that moral categories are easily defined, that action taken quickly and boldly will bring a favorable solution to any problem, and that a morally superior creature will win any conflict with ones less palatable. None of this is said; rather, it is encoded in the structure of the work. Consequently, the formula is entertaining, predictable and essentially conservative; and its message, conveyed at a level below the fully conscious, is generally reinforcing but ultimately forgettable in its individual details. A space opera, by the very nature of its real communication, cannot be genuinely extrapolative or thought-provoking. It must soothe, not ruffle.

Delany complicates, “problematizes” these space-opera assumptions — messing with our heads at a preconscious level. In doing so, however, he helped to alter and evolve sf readers’ capacity to perceive and make sense of space opera in this new way. He’s the Invader, messing with the too-narrow minds of us mere mortals.

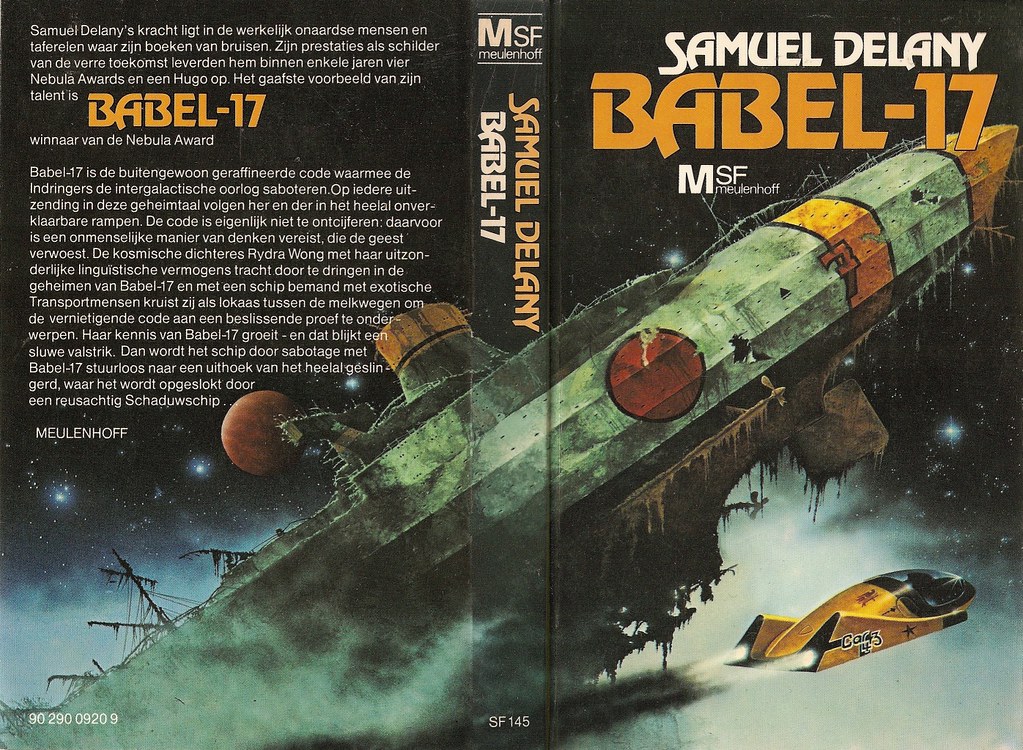

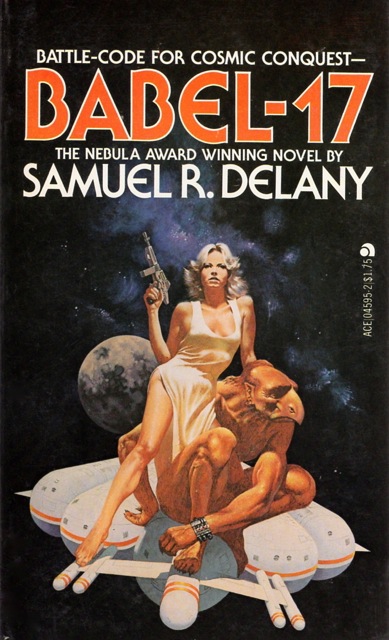

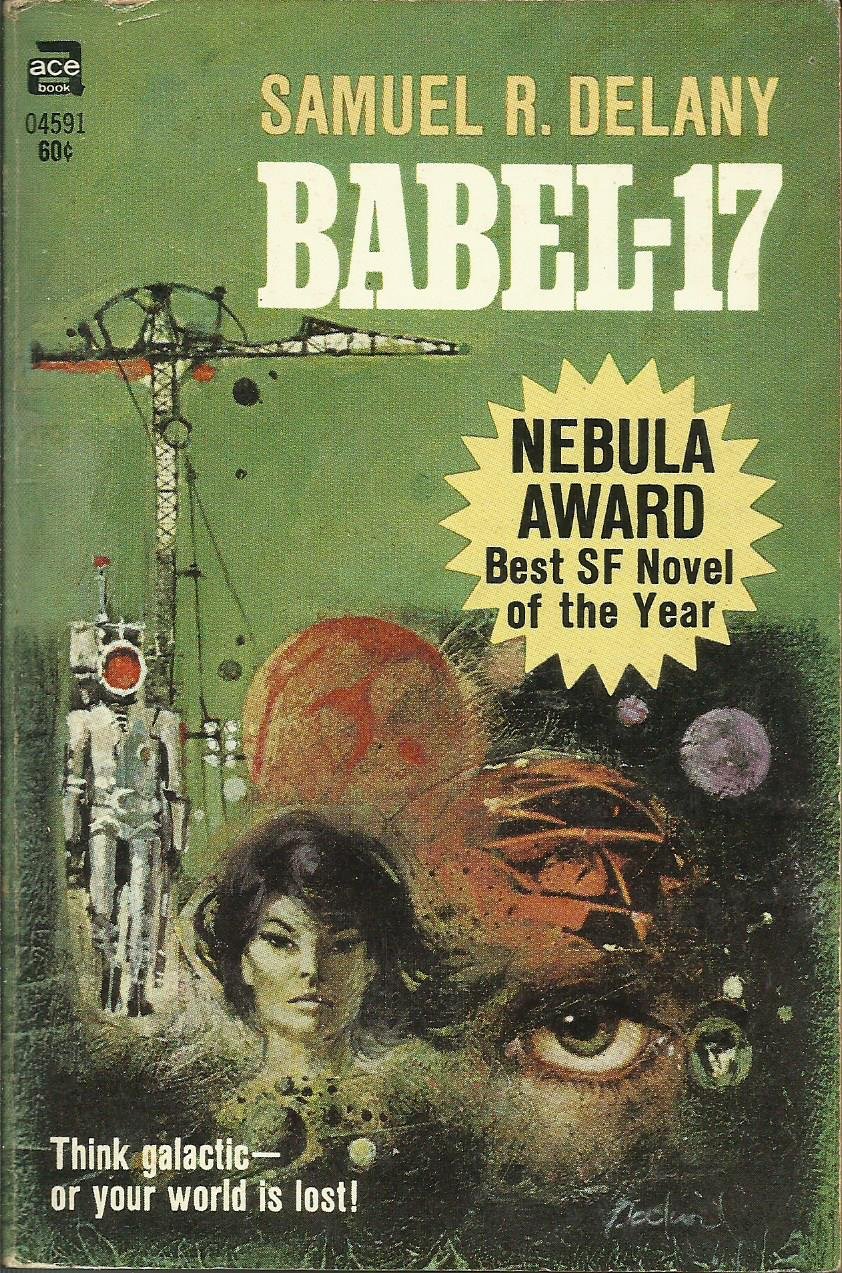

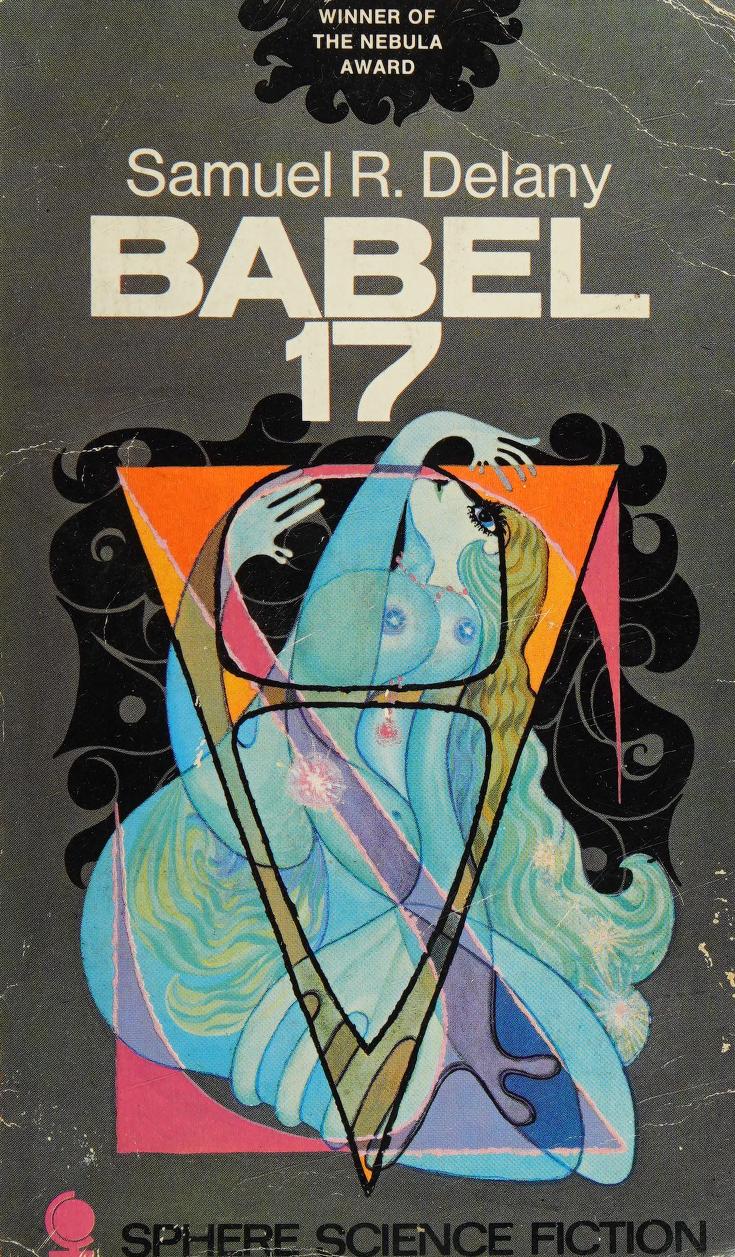

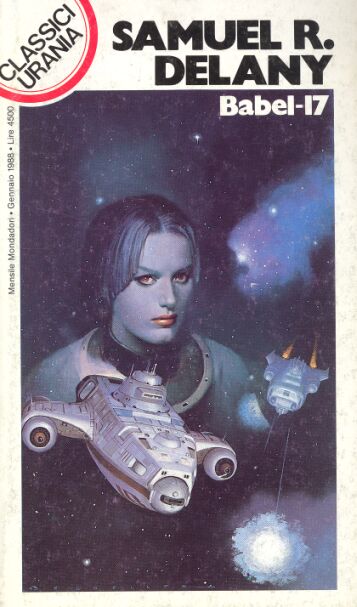

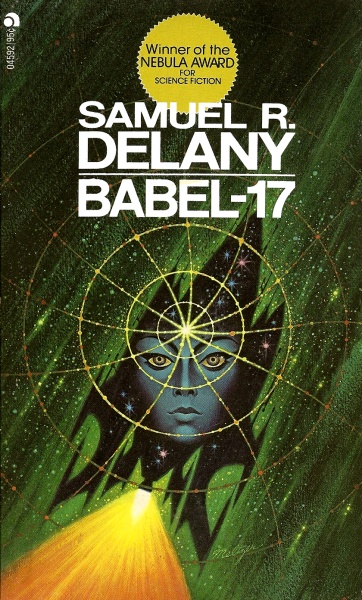

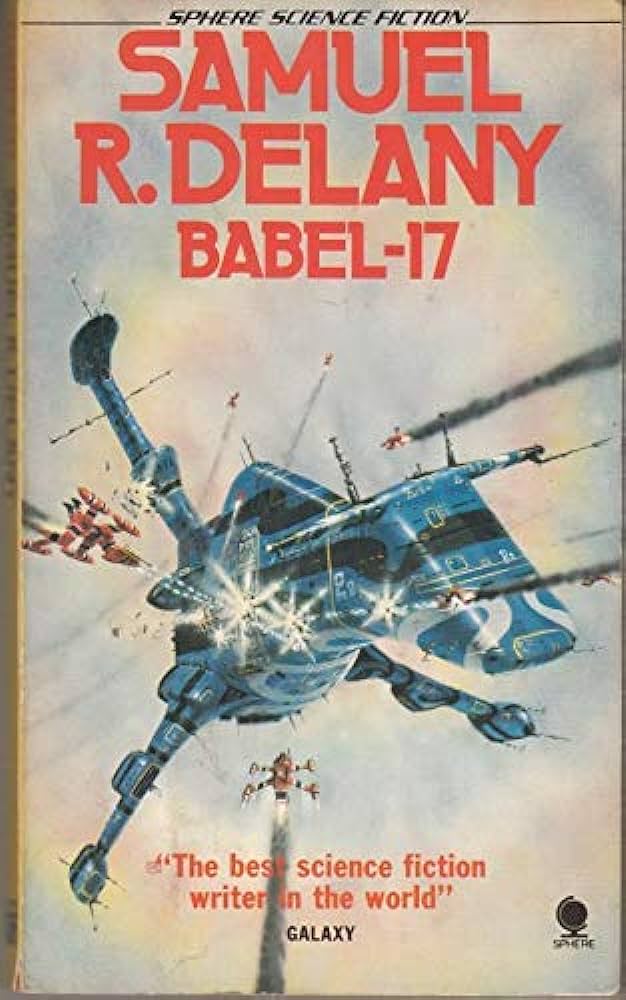

Check out the space-opera covers I’ve shared here. If the medium is the message, what expectations are being set for readers by these images?

JOSH GLENN’S *BEST ADVENTURES* LISTS: BEST 250 ADVENTURES OF THE 20TH CENTURY | 100 BEST OUGHTS ADVENTURES | 100 BEST RADIUM AGE (PROTO-)SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST TEENS ADVENTURES | 100 BEST TWENTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST THIRTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST GOLDEN AGE SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST FORTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST FIFTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST SIXTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST NEW WAVE SCI FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST SEVENTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST EIGHTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST DIAMOND AGE SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST NINETIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST HADRON AGE SCI-FI ADVENTURES.