OFF-TOPIC (58)

By:

March 4, 2024

Off-Topic brings you over-the-transom, on-tangent essays, dialogues and subjective scholarship on an occasional, impulsive basis. For this time, a collection of compasses to collective fiction, found memories and backward lived experience…

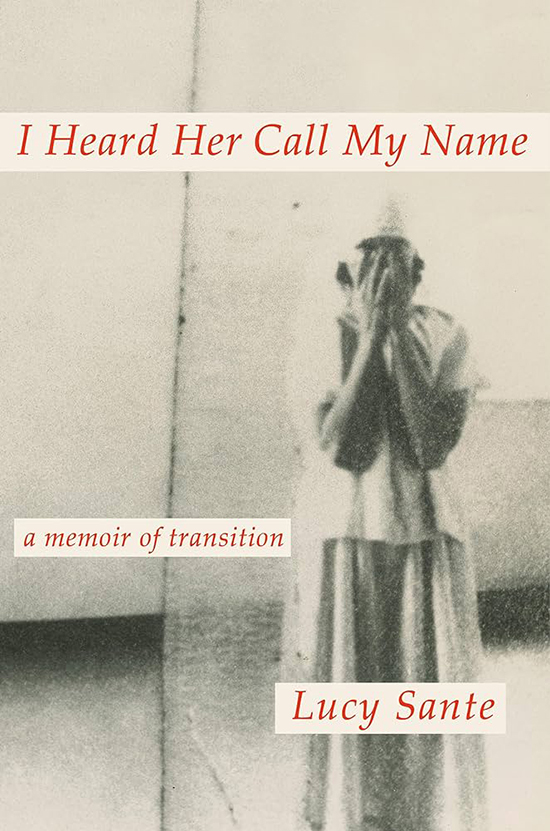

Our eyes snap the moment, but the meaning is developed over decades of memory. No one can map a mirage like Lucy Sante, and reading the memoir I Heard Her Call My Name (2024), a milestone in her oeuvre of eyewitness palimpsests of entire vanished eras, put me in mind of other fantasias of the ever-fading city — specifically New York, favored stage and shorthand for so much of what mass culture conceives of as defining our times. But if the past is another country (as one of my favorite cliches goes), then you can really be exiled from anywhere as you move through life, and you take a certain nationality from wherever the main dramas of your life play out. Portraits and perceptions of the Bay Area, the Jersey suburbs, Paris, Scandinavia, Rome and the Hudson Valley also blow through this text in the pristine clarity of a single point in time before they vanished and she vacated them. What Sante records is the unwritten history of becoming, and she tracks the diaspora of youth.

I Heard Her Call My Name travels the atlas of a culture — early-1970s to mid-1980s indie cinema, zine lit, renegade art, squatter salons, sexual pluralism, the united nations of the discotheque and the fertile hovels of punk — that was born invisible and is now ubiquitous. The teller is someone known to herself forever but herein met for the first time.

One strand of the story starts from Sante’s birth in Belgium in 1954 and moves forward though her emigration to New Jersey and bohemia beyond, historical moments evaporating along the way; alternating passages begin with Sante’s emergence as a trans woman in 2021 and reach backward, to summon and solidify the person who was gestating all that time. Diverging from a single starting point, I see the lines arcing up and back toward each other in the narrative shape of a heart.

A connection is traceable now between the self she was suppressing and both the absence she describes feeling from momentous social movements she was a party to, and the ambient remove from which she has always paradoxically and masterfully conveyed their atmosphere and texture. The past is a dream you wake up from, clutching the private proof of what you went through.

That history of what nobody knows happened is no easy thing to capture and can dissolve in its own light. This is why, ironically, trustworthy accounts of ephemeral times and places are more regularly found in fiction. Besides I Heard Her Call My Name, my other recent reference for the nonfiction kind is cartoonist T. Alixopulos’ Lipstick Traces (2021), a chronicle of his bygone clubbing and partying days (not in NY but LA), returned to him in fragments of time and sketches of vivid characters. The twinkling valley, conveyed in dancing geometric strokes, is a constant firmament above the scrubby suburbia rendered in scratchy verité; enchantment and blandness composed in a remarkable harmony of candor and charity as the aimless, harmless protagonists graze love and wisdom in the dark on their stumble toward adulthood. These stories from the hours when you should be sleeping shimmer at the fringe of cognitive logic and narrative reliability, but are that last long night of youth you carry into the rest of your waking life, refreshed.

Then there are the dreams you know you’re having, the nows that feel like memorials while they’re happening. The halcyon New York of I Heard Her Call My Name sent me back to HBO’s Girls (2012-17), which I’d drifted from mid-run, and returning to it I was stricken by what a signature Obama-era period piece it now seems. Completely contained within a moment of complacency and deceptive respite for youthful promise and social difference, its characters are acutely conscious of the tenuousness of their illusions and the tenacity with which they’re perpetuating them. Sante describes an alternative society that scavenged its economic sustenance and creative means from a city abandoned to crime and decay and populated by inventive exiles, before, as she puts it, “One day the big money would see the city as an undervalued property, and then it would be zipped out from under us”; a world-changing culture that flourished in the historical crevasse between New York’s former greatness and its later permanent bigness. By the time of Girls, the city’s surfaces have gotten too gleaming to hold onto for nearly as long; perpetual affluence makes its characters continually replaceable. The show, affectionately infamous for its petulant and privileged protagonists, is often lyrical in its eye for locale and sense of place, an evolving but eternal metropolitan stage set; in this New York, it’s the people that are the wreckage.

Plenty cinematic fictions painted the old, apocalyptic New York from life in a way which semi-idealized its struggles (Fame, 1980) or reverse-romanticized its shadows (Taxi Driver, 1976). These feed a legend of New York which the novelist Nikhil Singh has told me feels more authentic, or at least more accessible to him than the one we both can walk through; however, it constitutes the conceptual past of a latter-day, again culturally charged and materially ravaged New York in his forthcoming book Dakini Atoll, which, while displaced to the future, feels very recognizable to me. (Our full talk will appear here this summer.)

Just one pop-culture product I know of reports on Sante’s phantom city from on-location and in real time, Claudia Weill’s film Girlfriends (1978). Nothing takes an impression of those years of embattled expectation and civic malaise like this story of an aspiring photographer’s transient attachments and quiet daily survival. With a kind of wistfull bleakness, Weill conveys the emotional flavor of scraping along, the pace of waiting and hanging on. It’s remarkably attentive and individual in point-of-view for a film whose camera eye draws so little attention to itself; uncommonly shaped and forward-moving for a story structured at the rhythm of everyday drawn-out duty and existential drift. Sante has specialized in telling firsthand stories from outside the frame, and Weill’s avowed ambition was to center a subject who would be the sidekick in any other movie. We follow Susan Weinblatt as she holds her ground in a culture that could care less and a decade that won’t do her any favors; as she trudges from gig to gig shooting weddings and bar mitzvah boys; as her aspiring-writer best friend peels off into preordained married life; her older, also-married would-be lover breaks promises and a boyfriend makes demands; a runaway turned roommate wanders in and back out, trailing the implied tragedies of a whole other movie and then-plentiful headlines; and Susan finally presents herself for an appointment she doesn’t have with a gallery owner who admires the chutzpah and refers her for a solo show. Susan’s unapologetic independence and the film’s unmoralizing (and sometimes offhand) view, of amorous complexity, of reproductive choice, of the drug culture that was everywhere and the queer culture that was still clandestine, can feel like a different century in more ways than one; her journey from her Upper West Side flat to the Soho gallery district is a crossing of worlds, many of which would soon cease to exist. Weill made one more Hollywood movie before being driven out by sexist pressure and creative meddling (though she’s had a storied career in theatre and education). The sketchy, febrile outlands of the artworld Susan travels to were, by the middle of the next decade, a high-stakes hipster marketplace where the shabbiness was sanitized and women pushed down as far as ever. We don’t know what becomes of her, or what even really happened. But what matters is that we don’t forget.

MORE POSTS by ADAM McGOVERN: OFF-TOPIC (2019–2024 monthly) | textshow (2018 quarterly) | PANEL ZERO (comics-related Q&As, 2018 monthly) | THIS: (2016–2017 weekly) | PEOPLE YOU MEET IN HELL, a 5-part series about characters in McGovern’s and Paolo Leandri’s comic Nightworld | Two IDORU JONES comics by McGovern and Paolo Leandri | BOWIEOLOGY: Celebrating 50 years of Bowie | ODD ABSURDUM: How Felix invented the 21st century self | KOJAK YOUR ENTHUSIASM: FAWLTY TOWERS | KICK YOUR ENTHUSIASM: JACKIE McGEE | NERD YOUR ENTHUSIASM: JOAN SEMMEL | SWERVE YOUR ENTHUSIASM: INTRO and THE LEON SUITES | FIVE-O YOUR ENTHUSIASM: JULIA | FERB YOUR ENTHUSIASM: KIMBA THE WHITE LION | CARBONA YOUR ENTHUSIASM: WASHINGTON BULLETS | KLAATU YOU: SILENT RUNNING | CONVOY YOUR ENTHUSIASM: QUINTET | TUBE YOUR ENTHUSIASM: HIGHWAY PATROL | #SQUADGOALS: KAMANDI’S FAMILY | QUIRK YOUR ENTHUSIASM: LUCKY NUMBER | CROM YOUR ENTHUSIASM: JIREL OF JOIRY | KERN YOUR ENTHUSIASM: Data 70 | HERC YOUR ENTHUSIASM: “Freedom” | KIRK YOUR ENTHUSIASM: Captain Camelot | KIRB YOUR ENTHUSIASM: Full Fathom Five | A 5-part series on Jack Kirby’s Fourth World mythos | Reviews of Annie Nocenti’s comics Katana, Catwoman, Klarion, and Green Arrow | The curated series FANCHILD | To see all of Adam’s posts, including HiLo Hero items on Lilli Carré, Judy Garland, Wally Wood, and others: CLICK HERE