RADIUM AGE ART (1903)

By:

February 5, 2024

A series of notes regarding proto sf-adjacent artwork created during the sf genre’s emergent Radium Age (1900–1935). Very much a work-in-progress. Curation and categorization by Josh Glenn, whose notes are rough-and-ready — and in some cases, no doubt, improperly attributed. Also see these series: RADIUM AGE TIMELINE and RADIUM AGE POETRY.

RADIUM AGE ART: 1900 | 1901 | 1902 | 1903 | 1904 | 1905 | 1906 | 1907 | 1908 | 1909 | 1910 | 1911 | 1912 | 1913 | 1914 | 1915 | 1916 | 1917 | 1918 | 1919 | 1920 | 1921 | 1922 | 1923 | 1924 | 1925 | 1926 | 1927 | 1928 | 1929 | 1930 | 1931 | 1932 | 1933 | 1934 | 1935 | THEMATIC INDEX.

Please note that in my periodization schema, the years 1900–1903 are an interregnum of sorts, during which the seeds of science fiction’s Radium Age were planted. Thus, while artwork from this year (1903) may hint at the Radium Age proto-sf adjacent artwork to come, it may not exactly be something I’d want to describe with certainty as “Radium Age art.”

With the support of Renoir, Villon, and Rodin, the first Salon d’Automne opens in Paris — as a reaction to the conservatism of the Paris Salon. In addition to the 1903 inaugural exhibition, three other dates will prove historically significant for the Salon d’Automne: 1905 will bear witness to the birth of Fauvism; 1910 will witness the launch of Cubism; and 1912 will result in a xenophobic and anti-modernist quarrel in France’s National Assembly.

Isadora Duncan develops “free dance,” a dance technique influenced by the ancient Greeks and the philosophy of Nietzsche.

In 1903 Anna Muthesius published Das Eigenkleid der Frau, regarded as a seminal text in the development of early twentieth-century dress, and particularly associated with the Artistic Dress movement.

A 1903 book by Esprit Jouffret, Traité élémentaire de géométrie à quatre dimensions (Elementary Treatise on the Geometry of Four Dimensions), a popularization of Poincaré’s Science and Hypothesis in which Jouffret described hypercubes and other complex polyhedra in four dimensions and projected them onto the two-dimensional surface, will become influential on the development of Cubism. Maurice Princet, a French mathematician and actuary, will introduce the concept of the fourth dimension to Picasso, Apollinaire, Max Jacob, Jean Metzinger, Robert Delaunay, Juan Gris and later Duchamp. Princet has since become known as “le mathématicien du cubisme.”

The 1903 publication of An Introduction to Metaphysics would become a crucial guide for Bergson’s philosophy as a whole; this marks the beginning of “Bergsonism” — which would influence both modernist art (specifically Cubism) and, I believe, proto-sf literature too. See below.

Orville Wright flies an aircraft with a petrol engine, the Wright Flyer, at Kitty Hawk, North Carolina in the first documented and successful powered and controlled heavier-than-air flight.

Klimt’s sketches of frescoes commissioned for the great hall of the university are reproached by some critics for the excessive (some say: sickly) sensuality of his art.

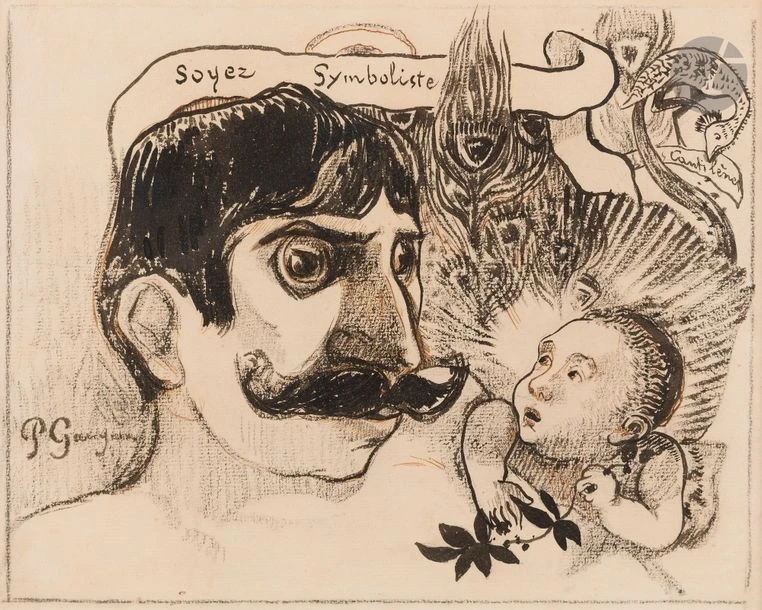

Paul Gauguin, who since 1888 had embarked on Symbolist painting, dies in poverty on the island of Hiva Oa. The bishop of the Marquesas describes him as “a famous artist, enemy of God and of all that is honest.”

Marie Curie and Henri Becquerel share the Nobel prize for their radium research.

Also see: RADIUM AGE: 1903.

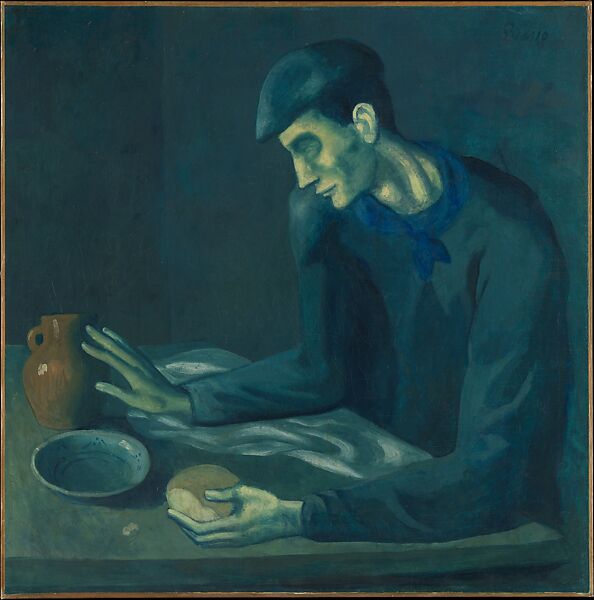

Picasso’s Blue Period works depict mentally and physically downtrodden characters in the greatly simplified style characteristic of pictorial Symbolism.

Bears a striking resemblance to H.R. Giger’s concept art for Alien.

See this website.

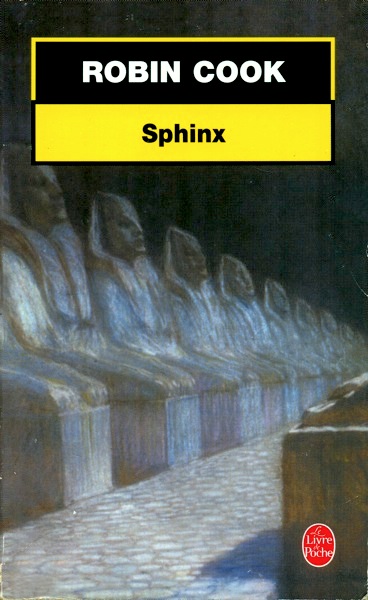

According to Audrey Wagtberg Hansen in her article “Cold Gods and Fatal Women: The Many Faces of the Sphinx in the 19th Century,” Kupka’s “Way of Silence II” was “inspired by Poe’s poem ‘Dream-land.’ Here we see a lone traveler on a seemingly endless road under a starry sky, flanked by two rows of stone sphinxes.”

Excerpt from Poe’s poem:

By a route obscure and lonely,

Haunted by ill angels only,

Where an Eidolon, named NIGHT,

On a black throne reigns upright,

I have reached these lands but newly

From an ultimate dim Thule —

From a wild weird clime that lieth, sublime,

Out of SPACE — Out of TIME.

See below for an example of this artwork used as an sf(ish) book cover illustration.

The Blue Rider (German: Der Blaue Reiter) is a 1903 painting by Wassily Kandinsky. It represents an important milestone on his artistic transition from impressionism to modern abstract art, of which he would be one of the pioneers. Kandinsky’s object-free paintings would eventually display spiritual abstraction suggested by sounds and emotions through a unity of sensation. For Kandinsky, blue was the color of spirituality: the darker the blue, the more it awakened human desire for the eternal (see his 1911 book On the Spiritual in Art).

See: Kandinsky artworks by year.

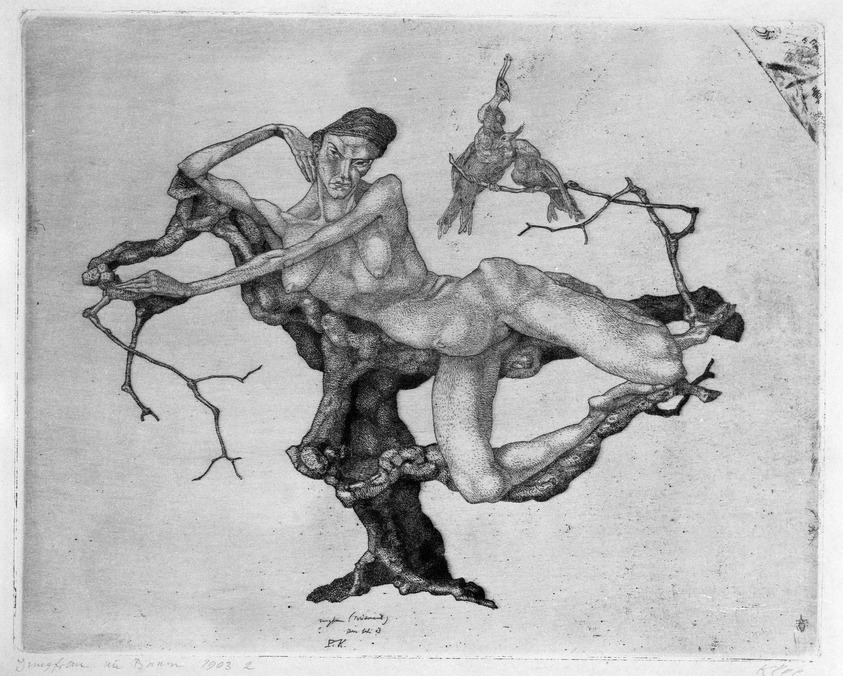

From the series Inventions (Inventionen). Rebelling against the classical training he had received at art school, Klee radically distorted the anatomy of the female nude in this series. By parodying the typically allegorical treatment of women’s bodies, he expressed his alienation from the bourgeois conservatism of mainstream art and his desire to retreat into his imagination.

As we read in the 2011 book German Expressionism: The Graphic Impulse, Expressionism would arise (1905 is usually given as the start date) out of

a feeling of dissatisfaction with the existing order, and a desire to effect revolutionary change. This attitude — rejecting bourgeois social values and the stale traditions of the state-sponsored art academies — was perhaps best reflected in Paul Klee’s 1903 etching Virgin in the Tree, a grotesque parody of the long convention of idealized or allegorical female nudes. Heeding a Nietzschean call for a transformation of values, many artists shared a hope for renewal and believed that the arts would play a central role. Their goal was to upend social norms, and, through an acute attention to thoughts, feelings, and energies that had long been repressed, to achieve a heightened understanding or awareness of what it was to be human. […] Directness, frankness, and a desire to startle the viewer characterize Expressionism in its various branches and permutations.

See this book.

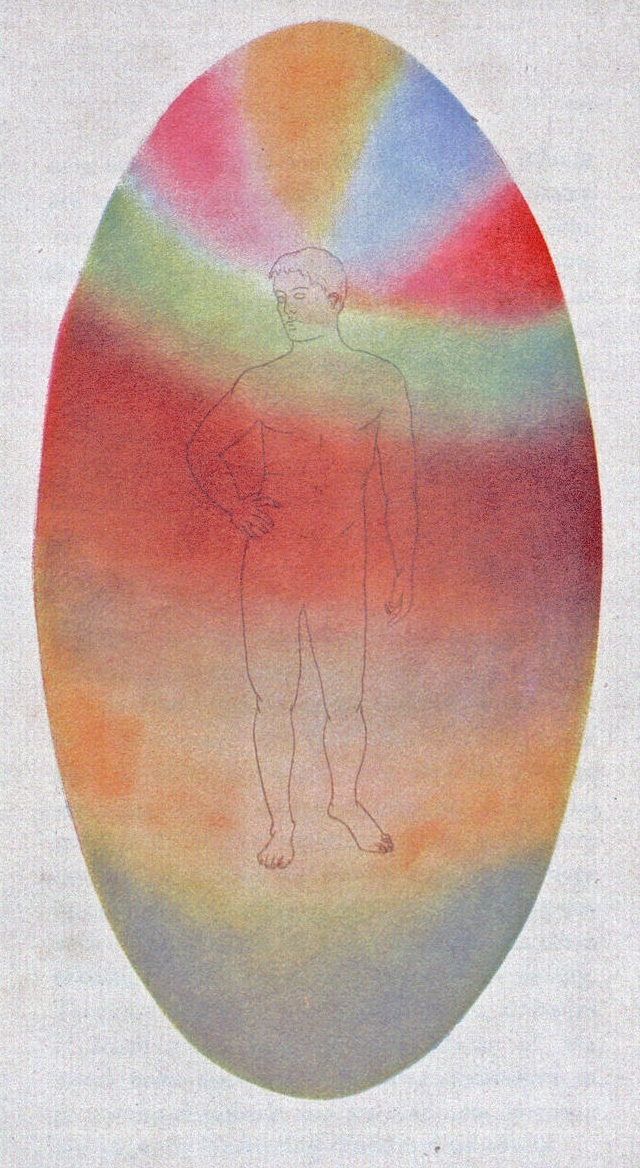

Delville depicts a cosmic Christ figure and humanity ascending. He adopted an original Symbolist style, influenced by esoteric theories.

Speaking of utopia, Pauline Hopkins’ Of One Blood (reissued by the MIT Press’s RADIUM AGE series) appears in 1902–1903.

Koloman Moser’s so-called “Purkersdorf Sanatorium Armchair” (1903)

Moser designed this chair for the first Vienna Secession exhibition, organized by Gustav Klimt. The chair would later become synonymous with the Purkersdorf Sanatorium, an artist’s retreat near Vienna created by the architect Josef Hoffmann.

NOTES ON BERGSONISM

Henri-Louis Bergson (1859–1941) was a French philosopher who was influential especially during the first half of the 20th century until the Second World War, but also after 1966 when Gilles Deleuze published Le Bergsonisme. Bergson argued persuasively that — for perceiving and comprehending reality as it truly is — processes of immediate experience and intuition are more significant than abstract rationalism and science. Bergson’s philosophy was controversial in his native country, where they were seen as opposing the secular and scientific attitude officially adopted by the Republic.

Bergson’s most influential works were written between 1889 (Time and Free Will) and 1907 (Creative Evolution). These are: Matter and Memory (1896), Laughter (1900) and An Introduction to Metaphysics (1903). His lectures at the College de France (where he was a professor from 1900) were immensely popular with students and intellectuals. Bergson’s philosophy played a major part in the “revolt against reason” in French culture from the late nineteenth century; his anti-positivist epistemology put intuition in the place of reason.

Via William James’s enthusiastic reading of An Introduction to Metaphysics, Bergsonism would influence Pragmatism.

In this essay, Bergson discusses duration — his term for reality, the absolute, a mobile unity-and-multiplicity that cannot be grasped through immobile concepts. (One already detects, here, a connection to the Pragmatist philosopher and pioneering semiotician C.S. Peirce — his notion of “firstness.”) Bergson conceptualized all experience into a binary opposition: life and death, intuition and intellect, memory and matter, perception and action, precision and indifference, creativity and dogmatism, durée and tout fait (that is: static achievement).

If we cannot directly perceive “duration,” how can we comprehend it? Via intuition, suggests Bergson. The best that we can hope for from analysis, from the creation of concepts, is relative knowledge — a static model of the real. We impose what Bergson calls a “geometric” order (our analysis) on the “vital” order of life. Intuition is about immersion in life… cf. James’s “radical empiricism.” Intuition is a theoretical activity — a faculty not merely of “seeing” but of “willing” — it consists, after some effort, in “transporting oneself” into the object known. Via intuition, the only faculty we possess that is coincident with a fluid reality.

In order that our consciousness shall coincide with something of its principle, it must detach itself from the already-made and attach itself to the being-made. It needs that, turning back on itself and twisting on itself, the faculty of seeing should be made to be one with the act of willing, — a painful effort which we can make suddenly, doing violence to our nature, but cannot sustain more than a few moments. — Creative Evolution

The French Cubist Raymond Duchamp-Villon, the Italian Futurist Umberto Boccioni, and the London-based Vorticist Henri Gaudier-Brzeska were all enthusiastic Bergsonians. (See Mark Antliff’s 2011 essay “Shaping Duration: Bergson and Modern Sculpture.” Also Sarah Kolb’s Speculative Art Histories, and Paul Atkinson’s Henri Bergson and Visual Culture: A Philosophy for a New Aesthetic.) These and other artists — Matisse, Marinetti, Gleizes, Metzinger — attempted to express “vital” dynamism in their art. Kolb notes that when Marcel Duchamp came to Paris in 1904, planning to start a career as an artist, Bergsonism was just about to reach its peak.

See R. Antliff’s Inventing Bergson, Cultural Politics and the Parisian Avant-Garde (1993), which argues that Bergson’s philosophy helped transmit Platonic and Neoplatonic notions into leading art currents – particularly Fauvism, cubism, and Futurism — in the first two decades of the twentieth century. (“Platonic” and “Neoplatonic” here suggest a search for a reality behind mere appearance; however, whereas Plato seeks an eternal reality behind flux, for Bergson — as for the pre-Socratics — flux is the eternal reality.) Also see: James Burton’s The Philosophy of Science Fiction: Henri Bergson and the Fabulations of Philip K. Dick (2017)

See the Science Fiction Encyclopedia entry on EVOLUTION. “Bergson’s theory of “creative evolution” … seems to have provided the seed of one of the most important UK evolutionary fantasies, J.D. Beresford’s The Hampdenshire Wonder (1911).” Indeed, the narrator of this novel is reading Bergson when he first encounters the Wonder.

In the SFE entry on SUPERMAN, we read: “It is very easy to love the notion of the superman if we believe that we might become supermen ourselves, or at least be parent to their becoming; it is for this reason that Bergsonian ideas are more frequently echoed in superman stories than Darwinian ones.” In addition to The Hampdenshire Wonder, this entry mentions E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man (1923) and Olaf Stapledon’s Odd John (1935) as examples of superman stories directly influenced by The Hampdenshire Wonder — and therefore indirectly by Bergson.

We also read, in the SUPERMAN entry: “In France, Bergson’s one-time pupil Alfred Jarry produced a comic erotic fantasia of superhumanity in The Supermale (1902).” The SFE’s entry on Jarry begins: “French author who carried the fruits of his scientific education into his surreal avant-garde writing, particularly the influence of the French evolutionary philosopher Henri Bergson.”

Julian Huxley, evolutionary biologist brother of Aldous Huxley, seems to have been influenced by Bergson; specifically, in j=his advocacy of what he called “transhumanism” through science-based command over evolution.

MORE RADIUM AGE SCI FI ON HILOBROW: RADIUM AGE SERIES from THE MIT PRESS: In-depth info on each book in the series; a sneak peek at what’s coming in the months ahead; the secret identity of the series’ advisory panel; and more. | RADIUM AGE: TIMELINE: Notes on proto-sf publications and related events from 1900–1935. | RADIUM AGE POETRY: Proto-sf and science-related poetry from 1900–1935. | RADIUM AGE 100: A list (now somewhat outdated) of Josh’s 100 favorite proto-sf novels from the genre’s emergent Radium Age | SISTERS OF THE RADIUM AGE: A resource compiled by Lisa Yaszek.