RADIUM AGE ART (1902)

By:

January 23, 2024

A series of notes regarding proto sf-adjacent artwork created during the sf genre’s emergent Radium Age (1900–1935). Very much a work-in-progress. Curation and categorization by Josh Glenn, whose notes are rough-and-ready — and in some cases, no doubt, improperly attributed. Also see these series: RADIUM AGE TIMELINE and RADIUM AGE POETRY.

RADIUM AGE ART: 1900 | 1901 | 1902 | 1903 | 1904 | 1905 | 1906 | 1907 | 1908 | 1909 | 1910 | 1911 | 1912 | 1913 | 1914 | 1915 | 1916 | 1917 | 1918 | 1919 | 1920 | 1921 | 1922 | 1923 | 1924 | 1925 | 1926 | 1927 | 1928 | 1929 | 1930 | 1931 | 1932 | 1933 | 1934 | 1935 | THEMATIC INDEX.

Please note that in my periodization schema, the years 1900–1903 are an interregnum of sorts, during which the seeds of science fiction’s Radium Age were planted. Thus, while artwork from this year (1902) may hint at the Radium Age proto-sf adjacent artwork to come, it may not exactly be something I’d want to describe with certainty as “Radium Age art.”

Georges Braque begins his studies at the Academie Humbert in 1902; there, he meets Marie Laurencin and Francis Picabia.

Edvard Munch exhibits extensively at this year’s Berlin Secession, including the first complete showing of his Frieze of Life series.

The first science fiction film, the silent Le Voyage dans La Lune, is premièred at the Théâtre Robert-Houdin in Paris, France, by actor/producer Georges Méliès, and proves an immediate success.

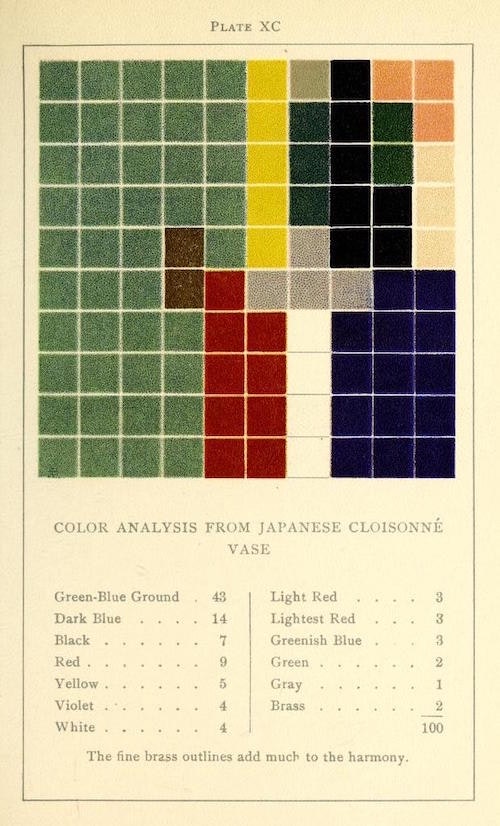

Color Problems, which has 400 pages and 116 color illustrations, was brought back into print in 2018.

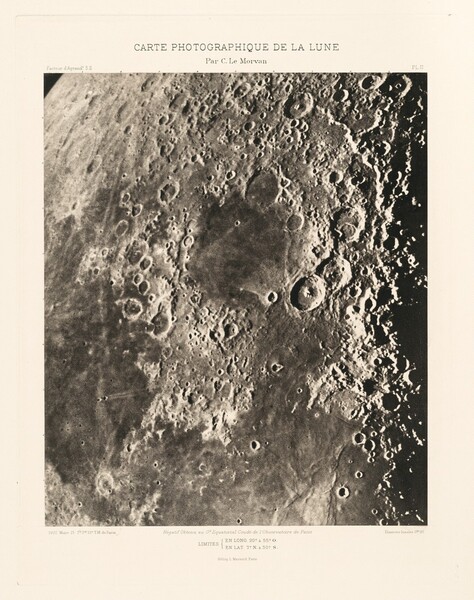

Beginning in 1894, Le Morvan, a young astronomer at the Paris Observatory, began assisting his colleagues Maurice Loewy and Pierre Puiseux with what would become the first comprehensive photographic atlas of the moon. The French astronomers obtained about 6000 photographs spread over 500 nights of observation. In 1914 Le Morvan used a selection of the same photographs to publish his own lunar map. This atlas was used until 1960, when the images obtained by space probes made it obsolete. Complete sets of this work are very rare.

Daniel Hudson Berman, architect and pioneer in the use of fireproof steel, erects the Flatiron Building in Manhattan. A kind of science-fictional spectacle, it becomes a tourist attraction.

Aesthetic: As Science of Expression and General Linguistic (1902), first of the “immanentist” Italian philosopher Croce’s most interesting philosophical ideas, is published. He argues that art collects and presents intuitions and expressions which are wider and more complex than those of the general experience; he rejects the idea that the artist could be satisfied with the imitation (i.e., creating a more or less perfect duplicate) of nature.

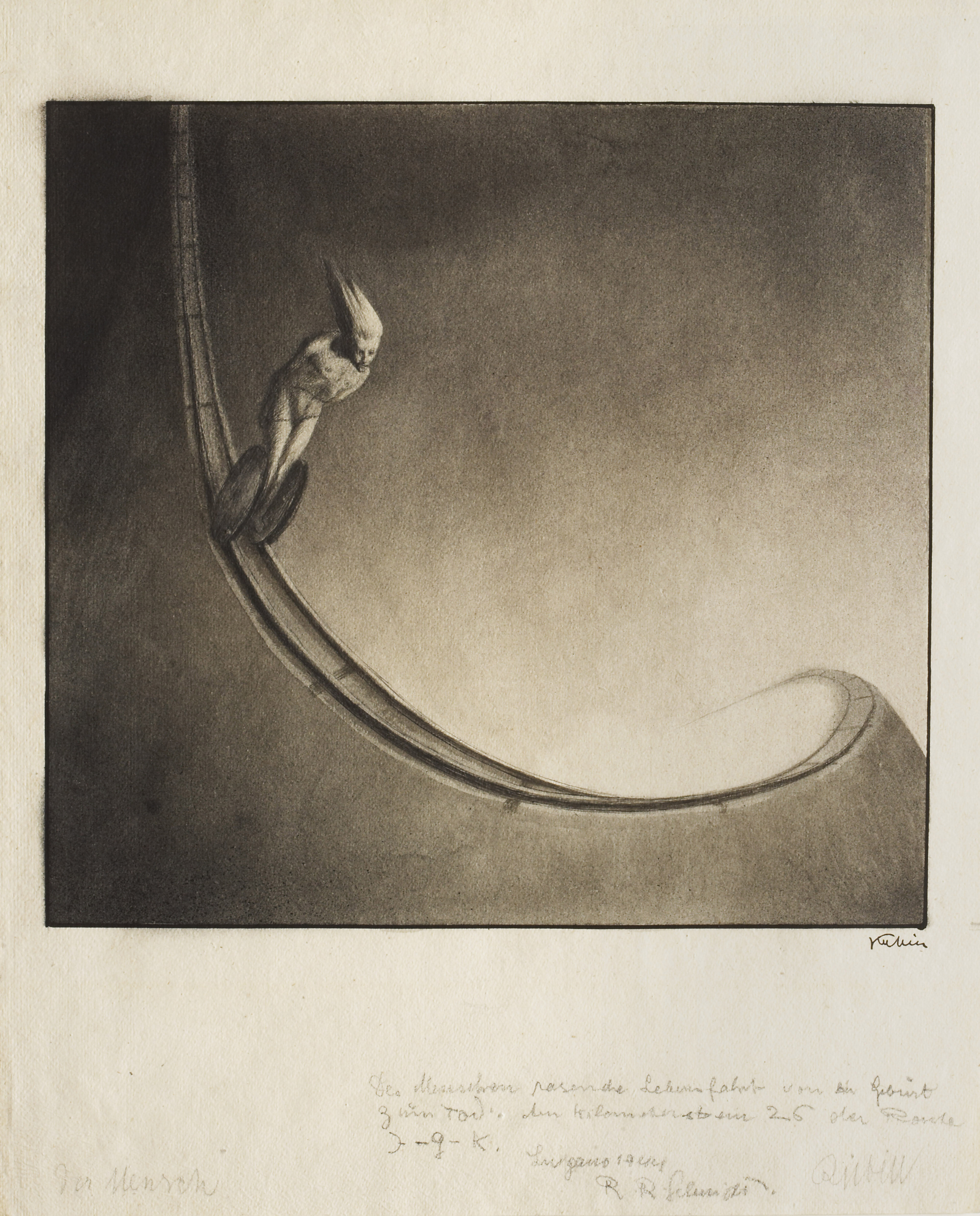

Alfred Kubin’s “Man” (c. 1902). “As if on the tracks of a roller coaster, whose course seems to draw our eyes in elegant curves and sways into a depth of blinding light, an anthropomorphic little figure mounted on a double wheel is racing downwards from a dizzying height at breath-taking speed,” we read at the Leopold Museum’s website. “In the following moments it will need to master a dangerous curve in the tracks and will subsequently disappear from our sight, vanishing in the glaring background.”

Something very Tron-like about this scenario.

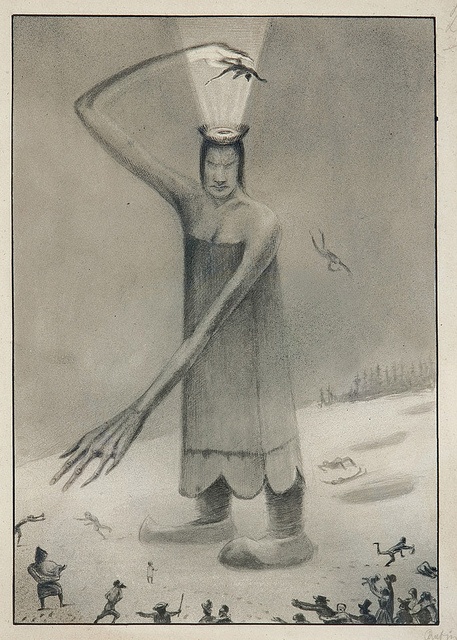

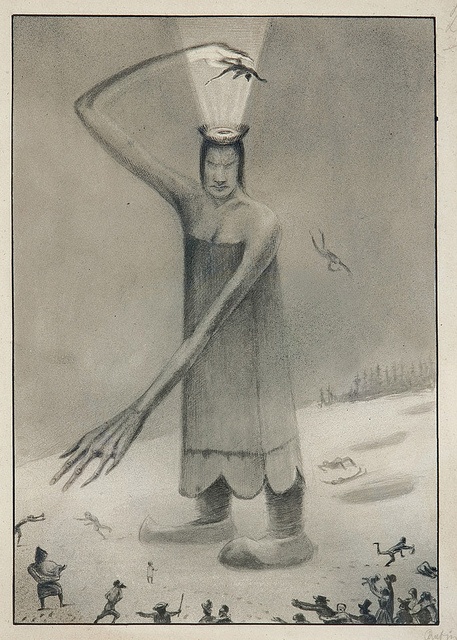

Jacek Malczewski’s “Angel of Death.” Malczewski (1854–1929) is regarded as the father of Polish Symbolism.

From the Met’s website: “The Hand of Man was first published in January 1903 in the inaugural issue of [Stieglitz’s journal] Camera Work. With this image of a lone locomotive chugging through the train yards of Long Island City, Stieglitz showed that a gritty urban landscape could have an atmospheric beauty and a symbolic value as potent as those of an unspoiled natural landscape. The title alludes to this modern transformation of the landscape and also perhaps to photography itself as a mechanical process.”

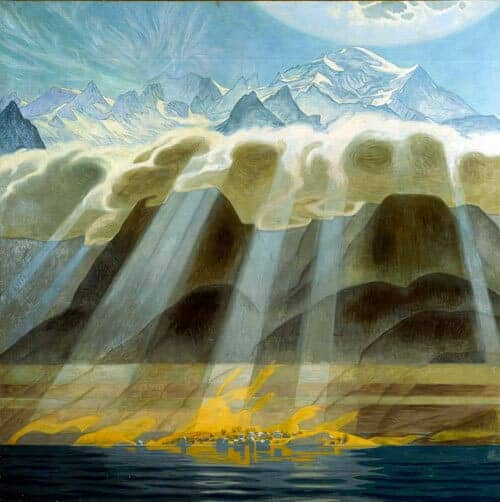

“The artist has suborned reality to the mystical effect given by the layering of light and the towering succession of horizons,” we read on the website of a Stockholm gallery. “Nature seems immense, both in scale and spirit, while the shoreside village appears to be burning in the glare of the light, a metaphor for man’s insignificance in the face of nature.”

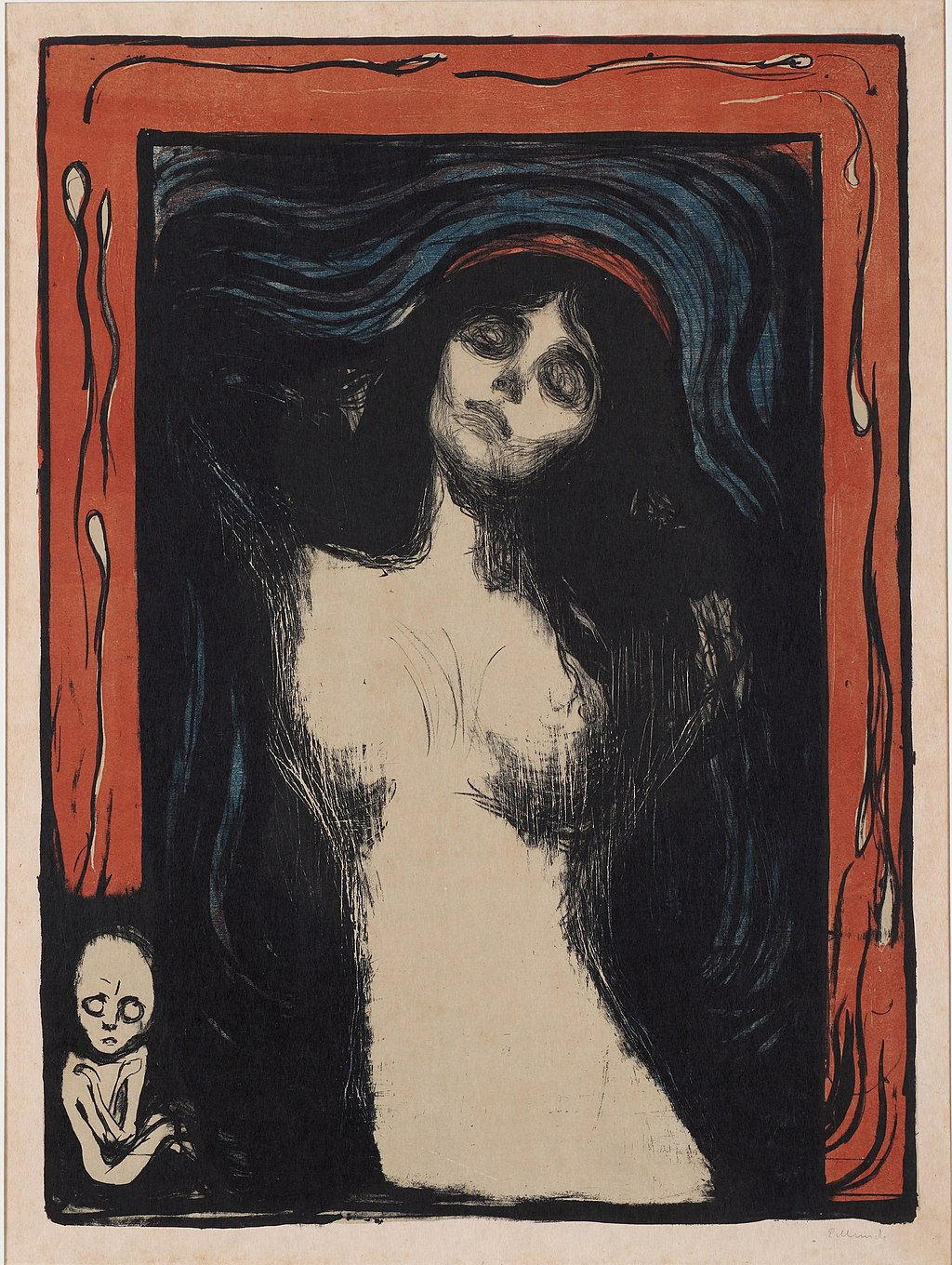

Munch’s Madonna (1852–1902) features not only an otherworldly figure but a little “gray man” figure at bottom left. From the book MoMA Highlights: 350 Works from the Museum of Modern Art New York (second edition, 2004):

Alluring and inviting, disturbing and threatening, Munch’s Madonna is above all mysterious. The erotic nude appears to float in a dreamlike space, with swirling strokes of deep black almost enveloping her. An odd-looking, small fetuslike figure or just-born infant hovers at the lower left with crossed skeletal arms and huge frightened eyes.

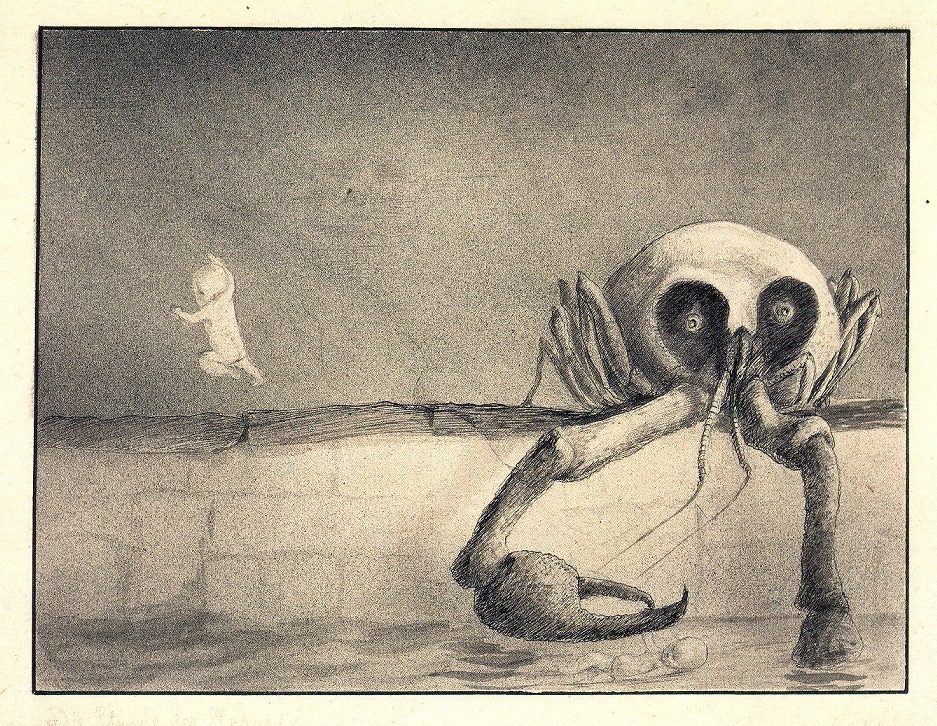

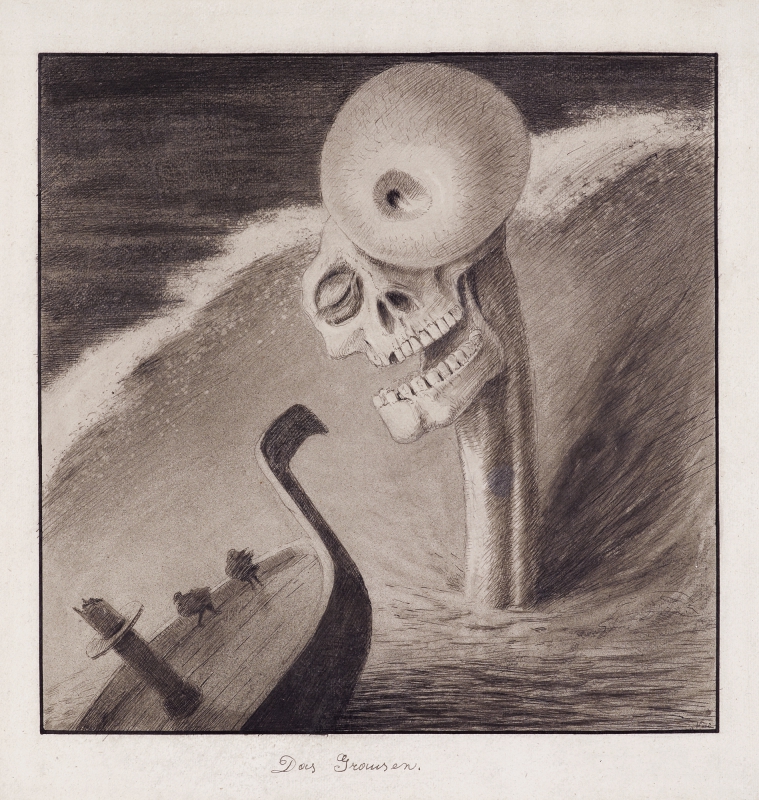

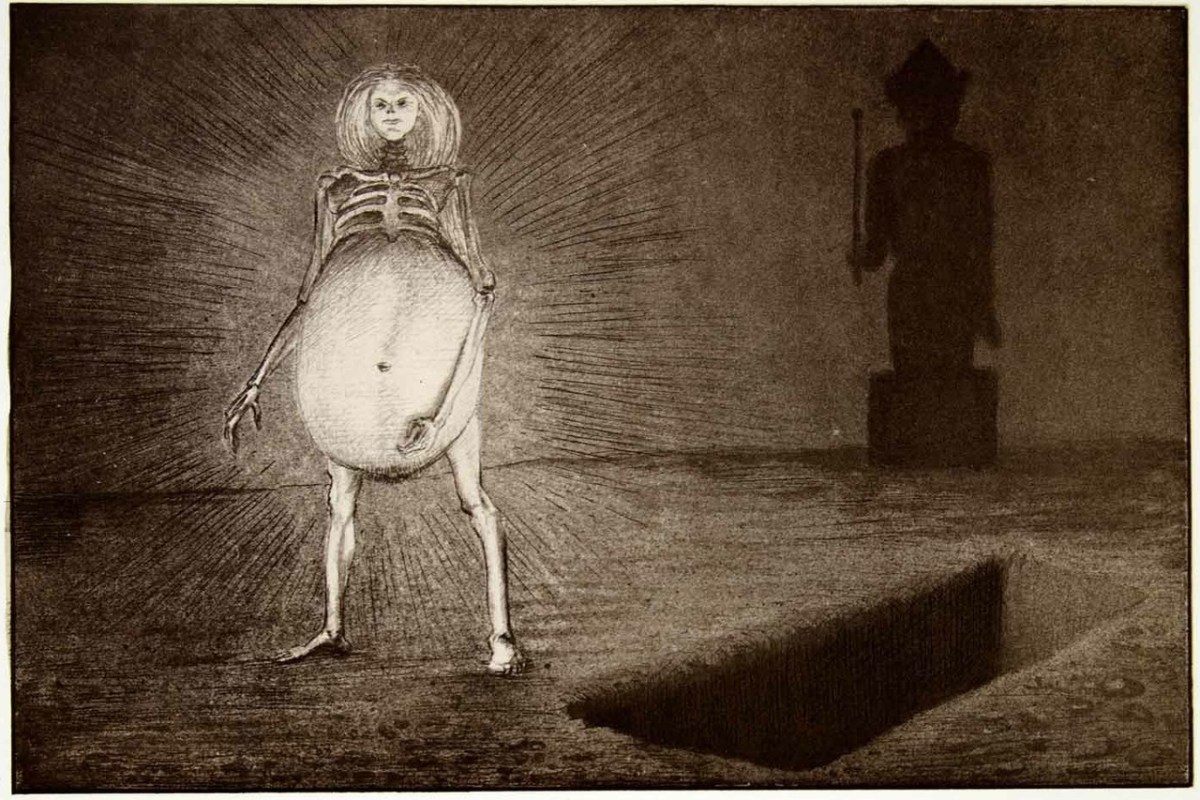

From the website Ferrebeekeper: “Kubin’s imagery was naturally seen through the psychosexual lens of Freudianism. He was claimed by the symbolists, and the expressionists. Yet his work seems to really exist in its own mysterious context. Kubin’s greatest works seem to involve a narrative which the viewer does not know, yet the outlines of which are instantly recognizable (like certain recurring nightmares).”

From the National Gallery of Art: “Gauguin purposefully displayed his Père Paillard and its female companion piece, Thérèse, in front of his Polynesian home (which he named the House of Pleasure), so that islanders passing by could appreciate the two carved works. Their meaning was evident to everyone. From Père Paillard (Father Lechery or Debauchery) inscribed on its base, they recognized the local Catholic bishop, Monseigneur Martin, who entreated Gauguin to stop his liaisons with local women, while pursuing them himself (with Thérèse and others) despite his vows of celibacy.”

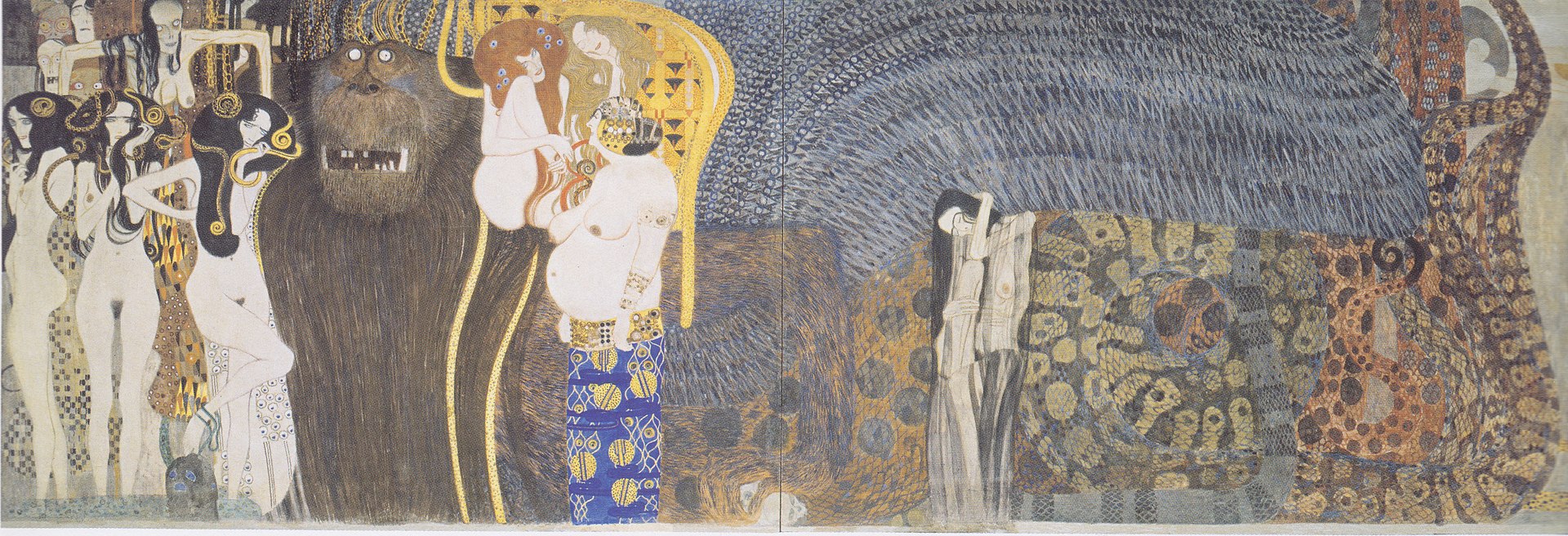

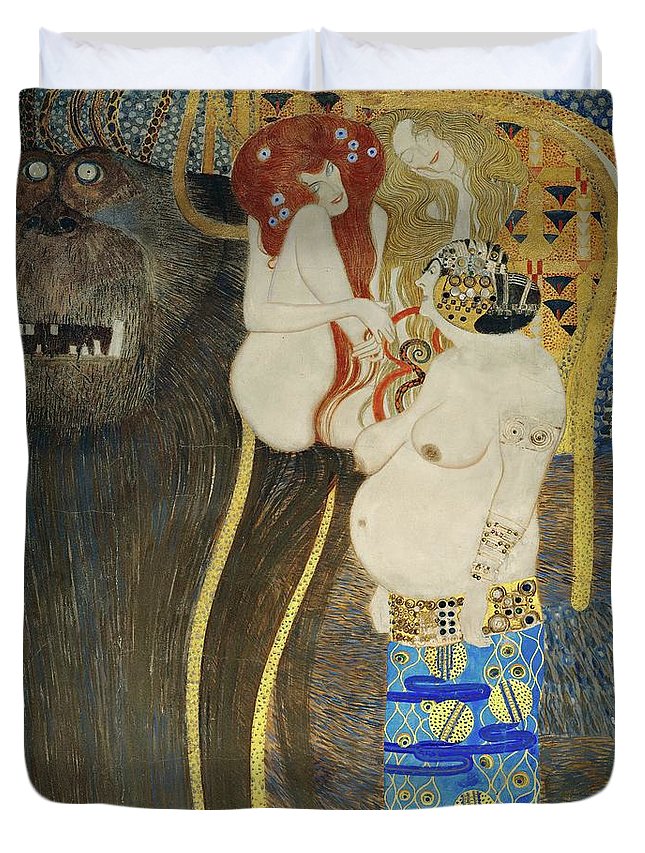

Typhaon / Typhos was a monstrous serpentine storm-wind giant — one of the deadliest creatures in Greek mythology. Klimt’s Beethoven Frieze shows “Typhoeus” (personificaton of the typhoid which plagued European cities at the time) with a simian aspect — though I think the wings and serpentine body to the right are part of the same creature. Lust, Voluptuousness and Intemperance (wearing a very cool skirt) are personified in female form.

MORE RADIUM AGE SCI FI ON HILOBROW: RADIUM AGE SERIES from THE MIT PRESS: In-depth info on each book in the series; a sneak peek at what’s coming in the months ahead; the secret identity of the series’ advisory panel; and more. | RADIUM AGE: TIMELINE: Notes on proto-sf publications and related events from 1900–1935. | RADIUM AGE POETRY: Proto-sf and science-related poetry from 1900–1935. | RADIUM AGE 100: A list (now somewhat outdated) of Josh’s 100 favorite proto-sf novels from the genre’s emergent Radium Age | SISTERS OF THE RADIUM AGE: A resource compiled by Lisa Yaszek.