SEMIOPUNK (11)

By:

January 17, 2024

An irregular, ongoing series of posts dedicated to surfacing examples (and predecessors) of the sf subgenre that HILOBROW was the first to name “semiopunk.”

BABEL (2022) | BABEL-17 (1966) | CAMP CONCENTRATION (1968) | A CANTICLE FOR LEIBOWITZ (1959) | CAT’S CRADLE (1963) | COSMONAUT KEEP (2000) | THE DIFFERENT GIRL (2013) | DOOM PATROL (1987–91) | THE EINSTEIN INTERSECTION (1967) | EMBASSYTOWN (2011) | ENGINE SUMMER (1979) | EXPLOITS AND OPINIONS OF DR. FAUSTROLL, PATAPHYSICIAN (1911) | FEERSUM ENDJINN (1994) | FLATLAND (1884) | FRIDAY (1982) | LE GARAGE HERMÉTIQUE (1976–79) | THE GLASS BEAD GAME (1943) | GLASSHOUSE (2006) | GRAVITY’S RAINBOW (1973) | THE HAMPDENSHIRE WONDER (1911) | LORD OF LIGHT (1967) | THE MAN WITH SIX SENSES (1927) | THE MOUNTAIN IN THE SEA (2022) | NINEFOX GAMBIT (2016) | ODD JOHN (1935) | PATTERN RECOGNITION (2003) | THE PLAYER OF GAMES (1988) | RIDDLEY WALKER (1980) | RODERICK (1980–83) | SNOW CRASH (1992) | THE SOFT MACHINE (1961) | SOLARIS (1961) | THE SPACE MERCHANTS (1953) | THE THREE STIGMATA OF PALMER ELDRITCH (1964) | TIME OUT OF JOINT (1959) | UBIK (1969) | VALIS (1981) | A VOYAGE TO ARCTURUS (1920) | VURT (1993) | WHITE NOISE (1985).

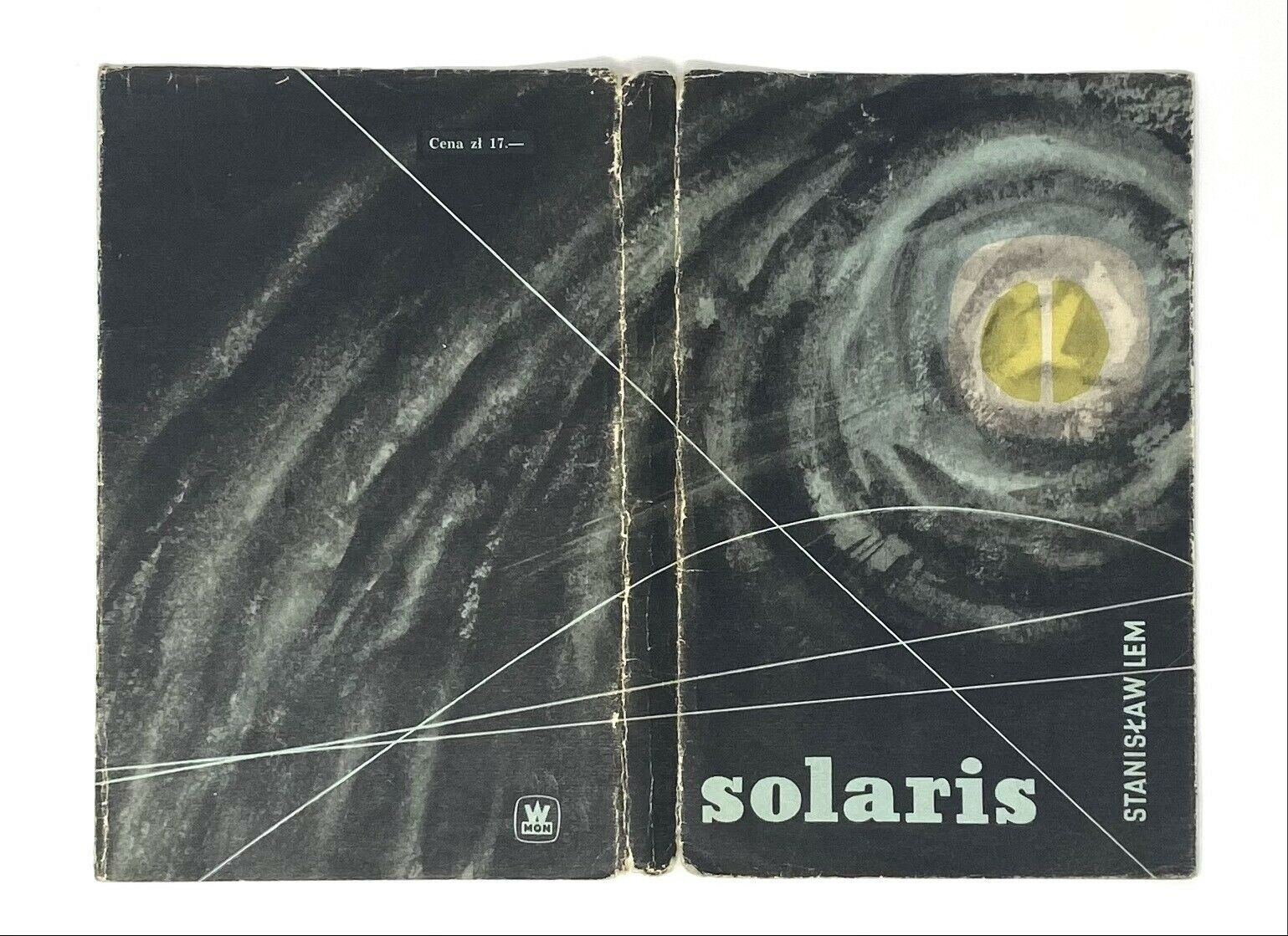

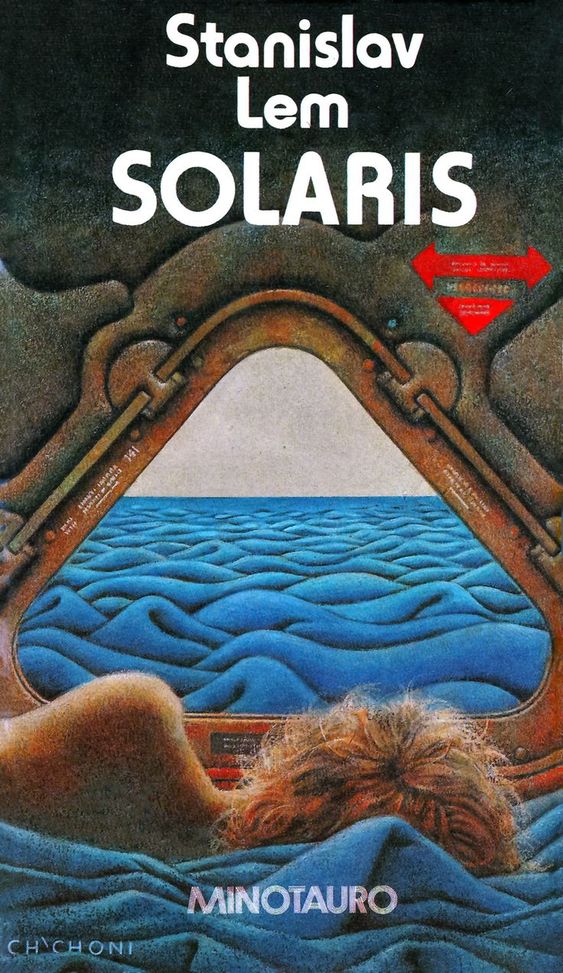

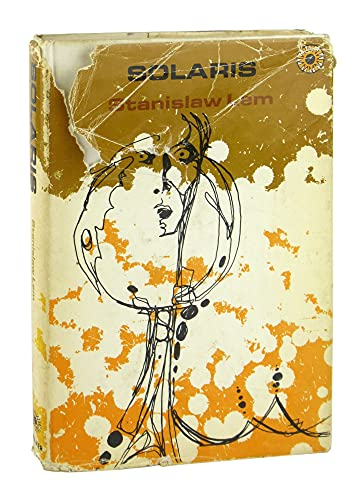

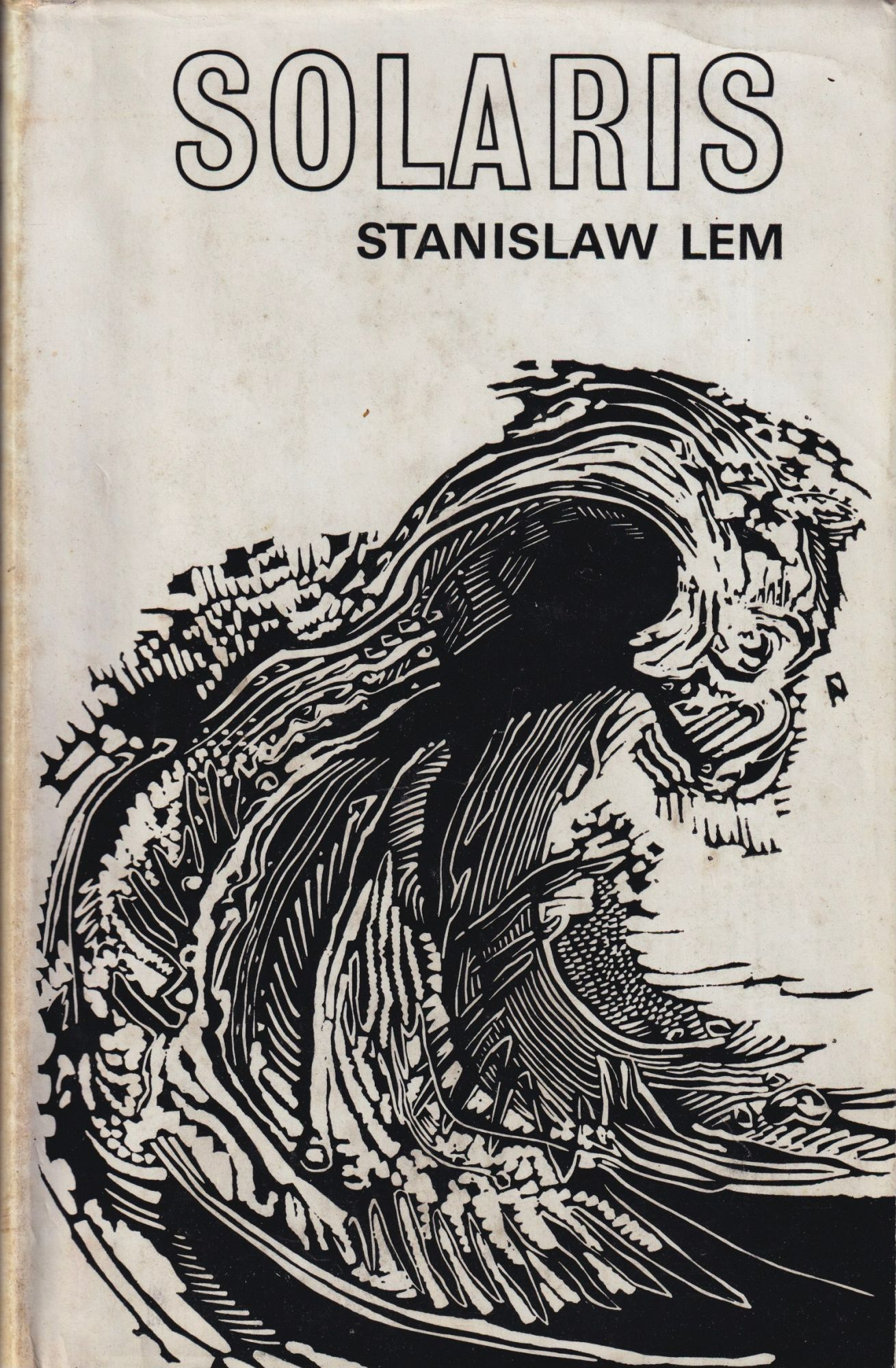

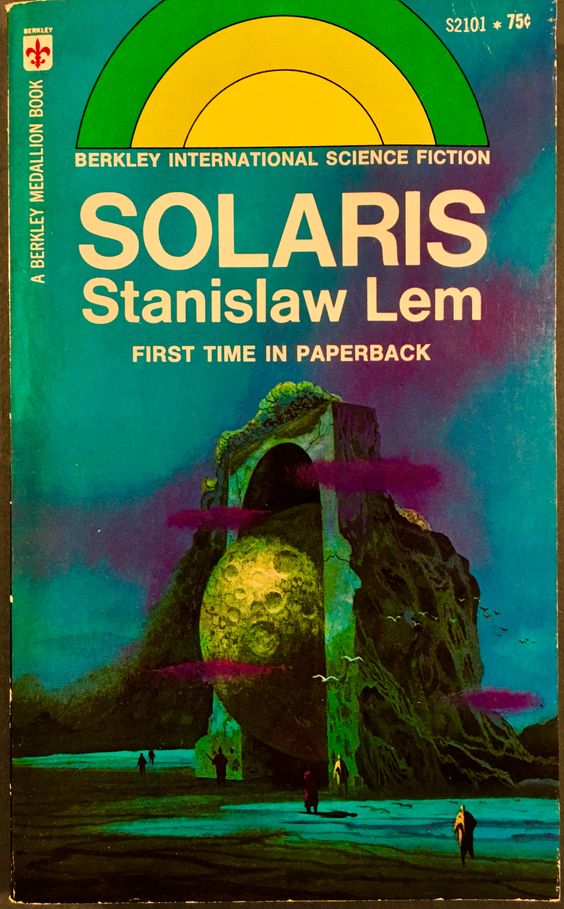

SOLARIS

Lem’s Solaris (1961) is a philosophical novel — at times dramatic and gripping, and at times academic and dry — asking the question, What would happen if we encountered an alien intelligence so exotic that we could in no way at all comprehend it?

Psychologist Kris Kelvin arrives, from Earth, aboard a scientific research station hovering near the gelatinous surface of the ocean-planet Solaris; this “ocean” appears to be a chthonic organism. The planet’s ocean-organism is constantly in flux, bringing forth massive outcroppings, mountains, flower-like structures, even city-like formations. For decades, a team of scientists has studied Solaris’s complex wave motions, but they haven’t been able to determine what these activities signify.

In 1989, Lem would observe, “the peculiarity of those phenomena [in Solaris] seems to suggest that we observe a kind of rational activity, but the meaning of this seemingly rational activity of the Solarian Ocean is beyond the reach of human beings.”

“I only wanted to create a vision of a human encounter with something that certainly exists, in a mighty manner perhaps,” Lem would say in a 2002 interview, “but cannot be reduced to human concepts, ideas or images.”

Saussure and Peirce agree that human concepts, ideas, and images are merely attempts to depict and communicate that which is beyond language. Lem’s novel isn’t about Solaris, really; it’s about the scientific discipline known as Solaristics — the echo with semiotics is amusing — which has degenerated over the years to simply observing, recording and categorizing the complex phenomena that occur on the surface of the planet’s “ocean.”

Think of Peirce’s “iconic” stage — the mental representation of visual stimuli in raw, unprocessed form. “Firstness” is how we experience things, Peirce notes — there is an innocence, a lack of categorization, an overwhelming sensory input. We experience the things of the world as “vagues” — they’re fuzzy, blobby, indeterminate. We engage in what Peirce named abductive hypothesizing — regarding these vagues — because we assume that there must be some way to categorize them, to organize this experience, to make sense of it — there must be similarities we can detect.

In “firstness,” perceptions flow over us as a whole — not broken into categorized and classified parts. What Peirce’s student William James would call a “blooming buzzing confusion.” What we actually experience are “vagues” — indeterminate perceptions that require further exploration. We grow our knowledge of these vagues through a process that is semiotic.

Knowing is never immediate and intuitive, semiotics would have us understand; it just seems that way. Knowing is a process so rapid that it feels immediate and intuitive. It feels like we’re holding a mirror up to nature, when in fact we build concepts from initially vague perceptions via a semiotic process — that is to say by using signs. We intuitively seek patterns that will help us organize these impressions and make sense. Such naive optimism is proven false, here.

All the solarists can do, despite their impressive theories, arguments, encyclopedias, research expeditions, monographs, and institutes — is build up “a never-ending ocean of factoids” (as Jonathan E. Hernandez, writing for Tor.com, puts it) that fail to solve Solaris’ perennial mysteries. The solarists’ ever-expanding map, if you will, obscures the territory.

Kelvin is the ideal scientist: at times stoic and collected, at times cold and aloof. Which doesn’t help him to comprehend Solaris.

Shortly before Kelvin’s arrival, the scientists have begun bombarding the ocean with high-energy x-rays. Apparently as a result of this experiment, the space station crew’s most painful and repressed thoughts and memories are actualized. Two of the scientists who have been living on the station and studying the planet have barricaded themselves in their cabins, before Kelvin arrives, and the third has committed suicide.

Each member of the crew, it seems, is visited by a lifelike simulacrum. Kelvin, for example, who feels guilty about the suicide of his lover, suddenly meets her again! We aren’t sure what the other scientists’ visitors look like — except for a “giant Negress” and a straw hat.

The horrified scientists can’t bring themselves to discuss what any of this might mean; their instinctive — unscientific — reaction is to destroy the simulacra.

Hernandez says the reader of Solaris is left to wonder: “To what extent can any of us understand one another, or ourselves? Is true understanding even possible? What does understanding imply? What is intelligence? Does knowledge itself have inherent value or is it merely a means to an end? Will a pursuit of knowledge ever satisfy our need to understand, or is it just another ego-driven attempt at grasping the unattainable?”

Fun fact: Solaris was adapted in 1972, by Andrei Tarkovsky, as a gorgeous but slow-moving film — which won the Grand Prix at the 1972 Cannes Film Festival. The 2002 Steven Soderbergh adaptation excludes Lem’s scientific and philosophical themes.

JOSH GLENN’S *BEST ADVENTURES* LISTS: BEST 250 ADVENTURES OF THE 20TH CENTURY | 100 BEST OUGHTS ADVENTURES | 100 BEST RADIUM AGE (PROTO-)SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST TEENS ADVENTURES | 100 BEST TWENTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST THIRTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST GOLDEN AGE SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST FORTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST FIFTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST SIXTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST NEW WAVE SCI FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST SEVENTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST EIGHTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST DIAMOND AGE SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST NINETIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST HADRON AGE SCI-FI ADVENTURES.