SEMIOPUNK (10)

By:

January 8, 2024

An irregular, ongoing series of posts dedicated to surfacing examples (and predecessors) of the sf subgenre that HILOBROW was the first to name “semiopunk.”

BABEL (2022) | BABEL-17 (1966) | CAMP CONCENTRATION (1968) | A CANTICLE FOR LEIBOWITZ (1959) | CAT’S CRADLE (1963) | COSMONAUT KEEP (2000) | THE DIFFERENT GIRL (2013) | DOOM PATROL (1987–91) | THE EINSTEIN INTERSECTION (1967) | EMBASSYTOWN (2011) | ENGINE SUMMER (1979) | EXPLOITS AND OPINIONS OF DR. FAUSTROLL, PATAPHYSICIAN (1911) | FEERSUM ENDJINN (1994) | FLATLAND (1884) | FRIDAY (1982) | LE GARAGE HERMÉTIQUE (1976–79) | THE GLASS BEAD GAME (1943) | GLASSHOUSE (2006) | GRAVITY’S RAINBOW (1973) | THE HAMPDENSHIRE WONDER (1911) | LORD OF LIGHT (1967) | THE MAN WITH SIX SENSES (1927) | THE MOUNTAIN IN THE SEA (2022) | NINEFOX GAMBIT (2016) | ODD JOHN (1935) | PATTERN RECOGNITION (2003) | THE PLAYER OF GAMES (1988) | RIDDLEY WALKER (1980) | RODERICK (1980–83) | SNOW CRASH (1992) | THE SOFT MACHINE (1961) | SOLARIS (1961) | THE SPACE MERCHANTS (1953) | THE THREE STIGMATA OF PALMER ELDRITCH (1964) | TIME OUT OF JOINT (1959) | UBIK (1969) | VALIS (1981) | A VOYAGE TO ARCTURUS (1920) | VURT (1993) | WHITE NOISE (1985).

THE SOFT MACHINE

To the extent that The Soft Machine (1961), the prose-poetic, radically deconstructive first installment in William S. Burroughs’s Nova Trilogy (which he would at one point describe as a sequel and “mathematical extension” of 1959’s Naked Lunch), has a plot, it appears in chapter VII. It could be described along the following science-fictional lines.

Using a time travel device, an agent able to transform his body via “U.T.” (undifferentiated tissue) causes the downfall of the Mayan empire. How? He infiltrates the Mayan slave laborers, who are mind-controlled by sounds recorded — by the priestly caste — onto magnetic tape (and also embedded in the Mayan calendar / codices).

I found out also that the priests themselves do not understand exactly how the system works and that I undoubtedly knew more about it than they did as a result of my intensive training and studies — The technicians who had devised the control system had died out and the present line of priests were in the position of some one who knows what buttons to push in order to set a machine in motion, but would have no idea how to fix that machine if it broke down, or to construct another if the machine were destroyed — If I could gain access to the codices and mix the sound and image track the priests would go on pressing the old buttons with unexpected results —

The agent replaces the priests’ tape with one broadcasting a revolutionary message: “Burn the books, kill the priests.”

If these sound like the lyrics to a heavy metal song, please note that the phrase “heavy metal” was first used in this novel, in a passage introducing the character “Uranian Willy The Heavy Metal Kid.” Lester Bangs, a Burroughs fan, would help smuggle the term into rock music criticism.

Lucy Sante, on Burroughs:

The continuous stream of Naked Lunch (1959), The Soft Machine (1961), Nova Express (1964), The Ticket That Exploded (1962), and innumerable chapbooks and broadsides, concluding with The Wild Boys (1971) is his summit, a recombinant petri dish of hallucinations and cut-ups and jokes and asides that can be read upside-down or backwards to much the same effect. The message is: You are the host of a virus; the virus is life; you are fucked.

In a 1973 Harper’s essay, “Playback from Eden to Watergate,” Burroughs boiled down his own message into a single phrase: “Language is a virus.”

By positing language as a force alien to humankind, and as the culprit responsible for the growth of social, cultural, and economic control systems, he sought to challenge the reading and thinking habits of his audience — and in doing so to undermine totalizing systems of thought.

Truth, for Burroughs, is a reified fiction that acts to suppress possibility. This millennia-long operation, which Burroughs calls the Nova Conspiracy, transforms humans into automatons — soft machines — whose perceptions and behavior are predetermined by sociocultural coding. How to break free from neo-fascist control mechanisms?

Burroughs’s “understanding of the force of language, the danger it poses to free and evolving life, and just what a writer is supposed to do about it anyway,” Brent Wood writes in a 1996 issue of Science Fiction Studies, has influenced sf writers ever since — including J.G. Ballard, who called Burroughs “the most important writer to emerge since the Second World War,” and perhaps most notably William Gibson and other cyberpunk pioneers.

Fun fact: In Neuromancer, Gibson casts Burroughs’ voice, personality, and insight as “McCoy Pauley” — the ROM construct that guides the novel’s protagonist in his cyberspatial mission.

The Harper’s essay mentioned above was part of a larger project, which Burroughs sometimes called “The Invisible Generation.” Through it, he appealed to youth and the alternative, counter-cultural press to “disrupt the exercise of power” by using some of the guerrilla resistance techniques — against the language virus — that he’d pioneered. Note that the oldest members of the 1944–1953 Blank Generation were in their teens when The Soft Machine appeared; and this cohort’s youngest members were turning 20 when the Harper’s article appeared.

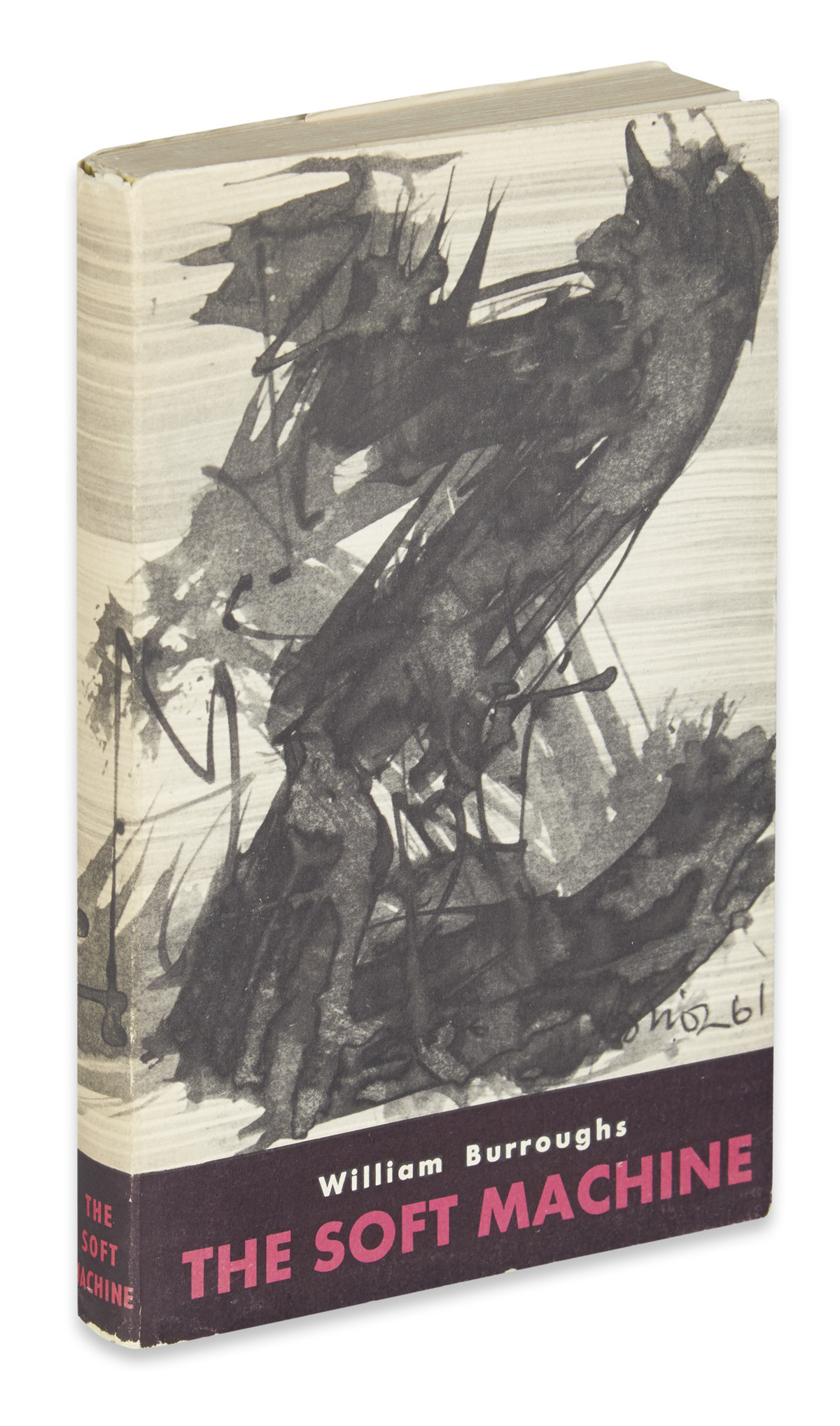

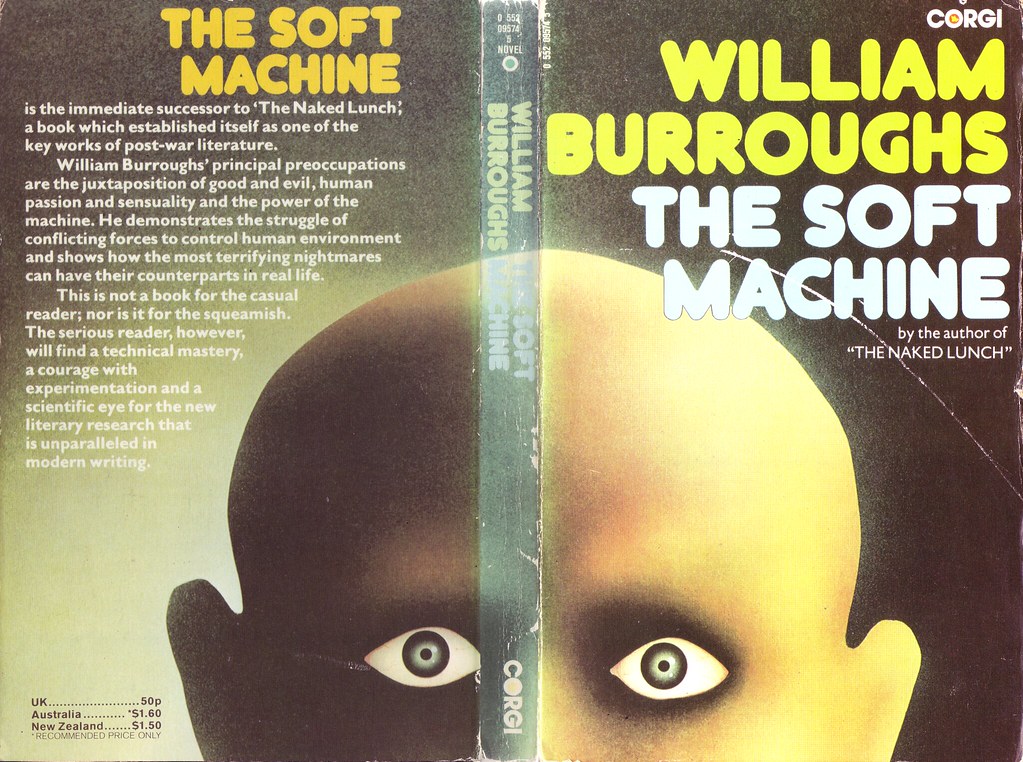

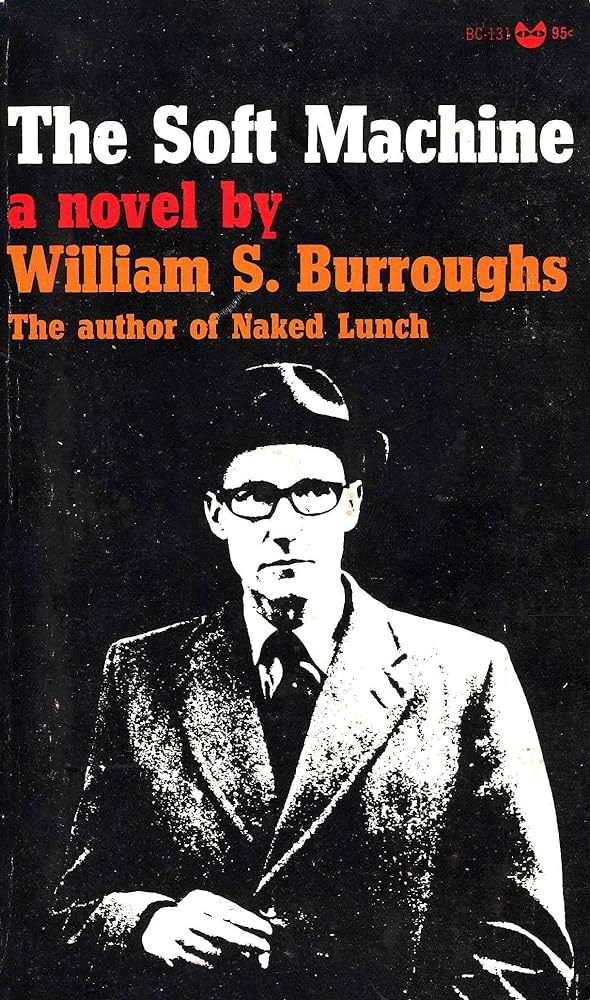

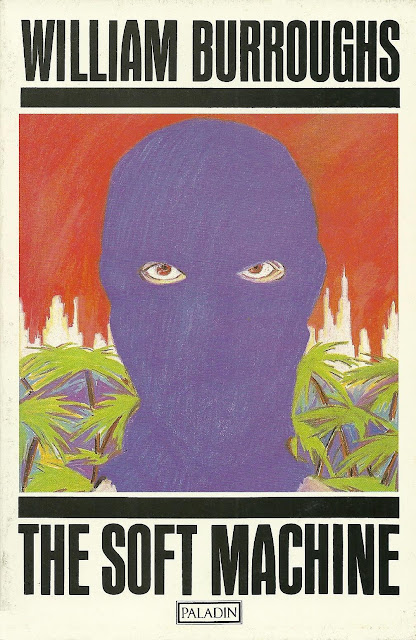

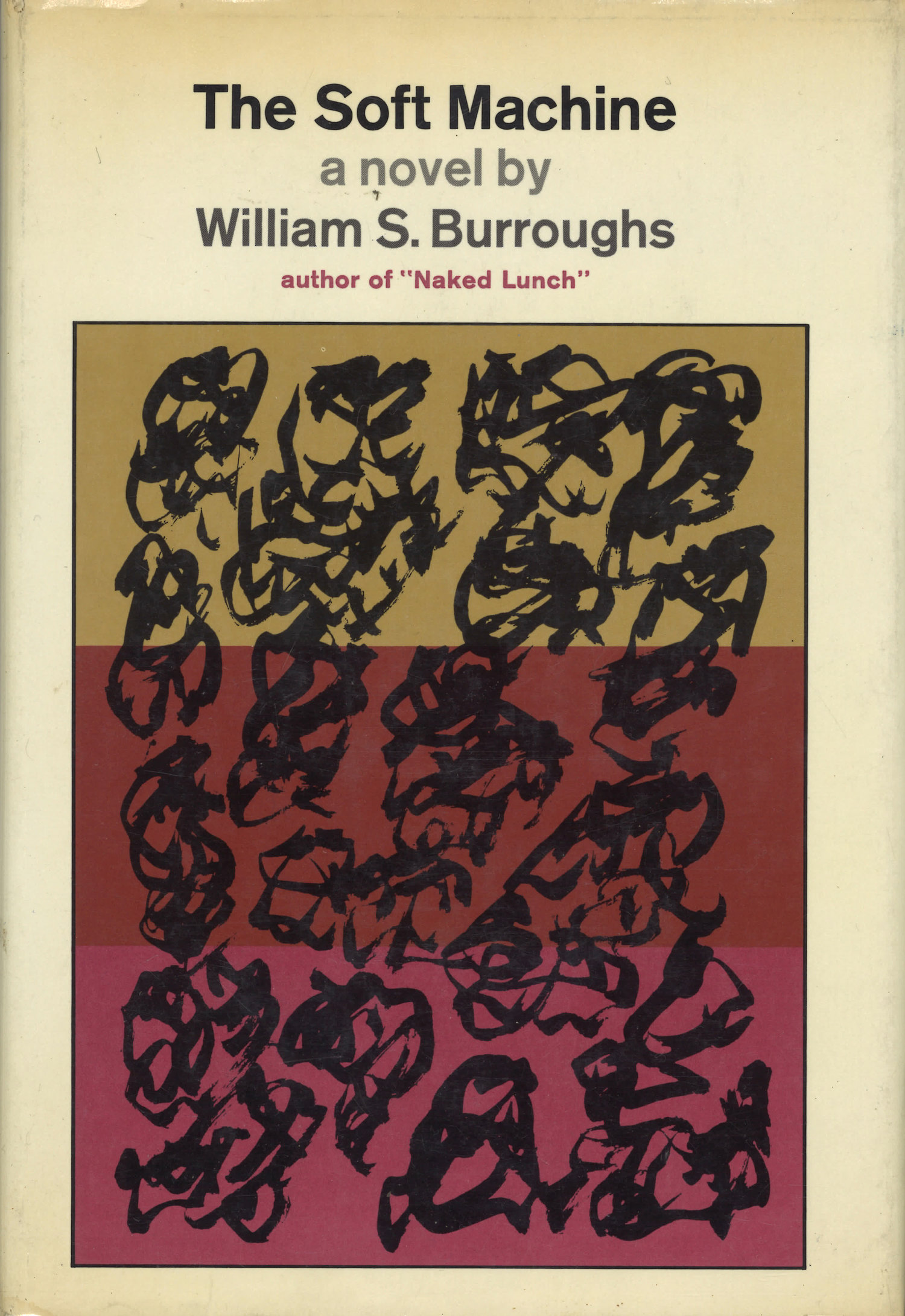

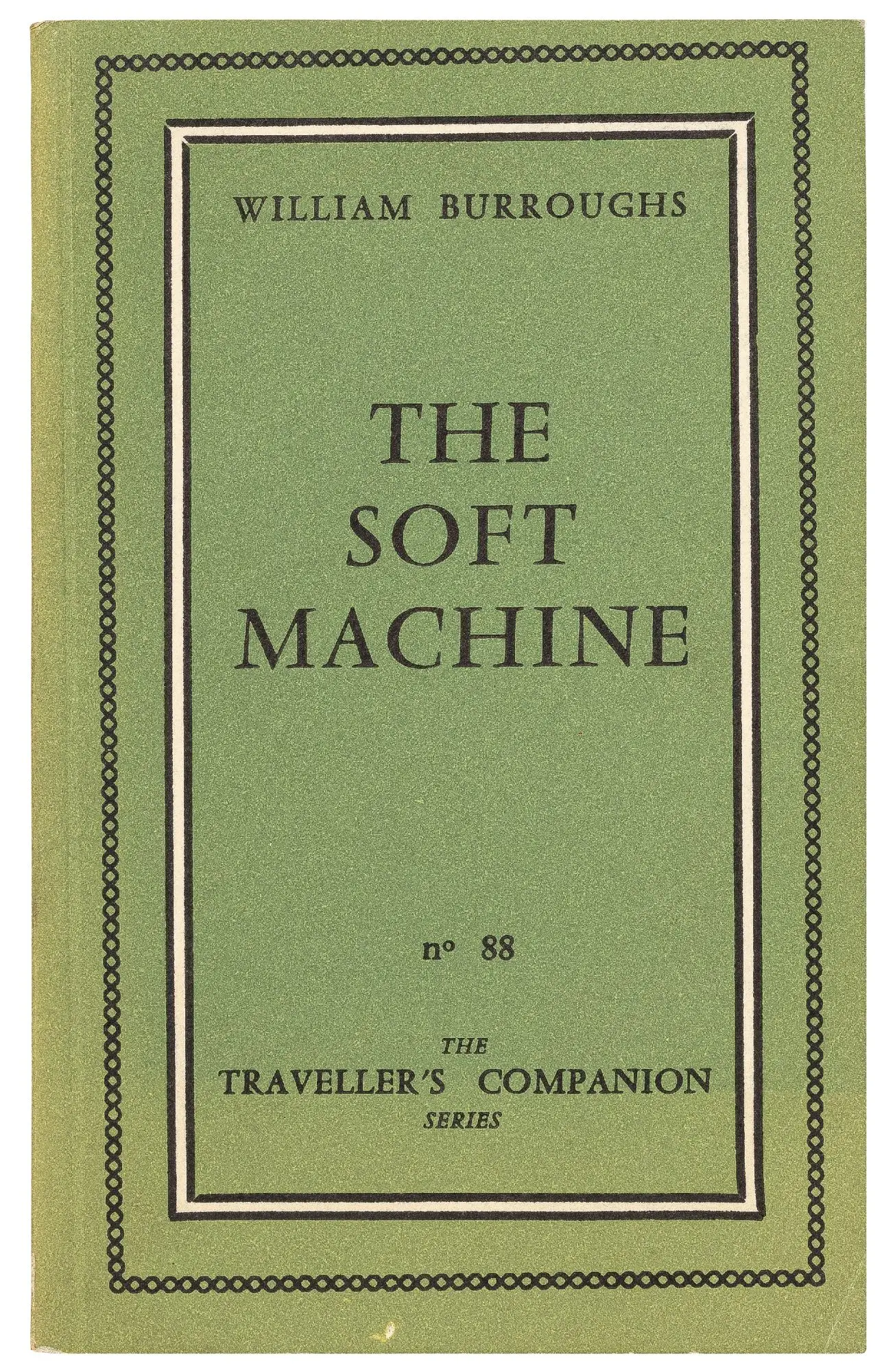

The first edition was printed by Olympia Press in Paris, in 1961; Burroughs was displeased with this version. The second edition was printed by Grove Press in the United States, in 1966. In this edition, Burroughs removed 82 pages and inserted 82 new pages, and the remaining 100 pages were rearranged and restructured using further cut-ups. Much of the added material was linear, narrative prose, which is arguably easier to read than the disorganized first edition. The third edition was printed by John Calder in Great Britain, 1968. This time most chapter titles were intact from the second edition, but they began at more natural places in the text, whereas the second edition could place them in the middle of a sentence.

In 2014, restored editions of the three novels were published, edited by Burroughs scholar Oliver Harris. The new editions made a number of changes to the texts and included notes and previously unpublished materials that showed the complexity of the books’ manuscript histories and the precision with which Burroughs used his methods.

The “cut−up” to which Lucy Sante refers above is an aleatory literary technique in which a written text is literally, physically cut up and rearranged to create a new text. Pioneered by the Dadaists, it was popularized in the 1950s and ’60s by Burroughs (who’d credit Eliot’s The Waste Land and John Dos Passos’ U.S.A. trilogy as inspiration, and who learned about the technique from Brion Gysin).

The cut-up serves as one of Burroughs’s principal weapons in the fight against the controlling power of the “track.” At the core of The Soft Machine, as noted, is the postulation that language is a method of control that forces us to perceive the world in a certain, fixed way; these perceptions place limits on our interactions. The “word track” inevitably moves away from plurality towards uniformity, leading us further and further away from the inherently “multi−leveled structure of experience.” By throwing up unlikely juxtapositions and permutations that force the readers into adjusting their approach to reading, the cut−up can expose the seemingly natural, inevitable, permanent “word track” — and wake us up to language’s power to shape our perceptions of what is socio-culturally possible.

Like Naked Lunch, The Soft Machine was assembled in part from the “Word Hoard,” a number of manuscripts Burroughs wrote mainly in Tangier, between 1954–1958. The Soft Machine and its two sequels were composed using the cut-up technique.

The characters Dr Benway, Clem Snide, Sailor, Bill Gains, Kiki, and Carl Peterson — whom we’d met before in Burroughs’s novels Junkie, Queer and Naked Lunch, turn up here again. And we meet here for the first time various characters who will reappear in the subsequent series installments. For instance, the Nova Mob: Mr. Bradly–Mr. Martin [sic], Sammy the Butcher, Green Tony, Izzy the Push, Willy the Rat/Uranian Willy, and Agent K9.

Nova Express is about a conspiracy by the Nova Mob to “infect” humans with an information virus, thus bringing about the destruction of Earth. Inspector Lee and the Nova Police are opposed to them, but also in a symbiotic relationship; because without the Nova criminals there would be no Nova police.

We also meet: Inspector Lee of the Nova Police. Alien races, both green- and blue-skinned. Plus intertextual characters appropriated from other novels, like Rudyard Kipling’s Danny Deaver (a British soldier executed in India for murder) and Herman Melville’s Billy Budd and Captain Vere.

In addition to time travel, The Soft Machine circles around themes of media bombardment, sexuality, and out-of-body travel. According to Burroughs: “I am attempting to create a new mythology for the space age.”

Joan Didion: “The voice in The Soft Machine is talking about time…. [It] slips deliberately and frequently, sometimes ironically and sometimes not… rattles off elliptical allusions, throws away joke after outrageous joke, shifts gear in mid-sentence, never falters. It is precisely this voice — complex, subtle, allusive — that is the fine thing about The Soft Machine and about Burroughs.”

JOSH GLENN’S *BEST ADVENTURES* LISTS: BEST 250 ADVENTURES OF THE 20TH CENTURY | 100 BEST OUGHTS ADVENTURES | 100 BEST RADIUM AGE (PROTO-)SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST TEENS ADVENTURES | 100 BEST TWENTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST THIRTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST GOLDEN AGE SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST FORTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST FIFTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST SIXTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST NEW WAVE SCI FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST SEVENTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST EIGHTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST DIAMOND AGE SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST NINETIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST HADRON AGE SCI-FI ADVENTURES.