SEMIOPUNK (5)

By:

October 6, 2023

An irregular, ongoing series of posts dedicated to surfacing examples (and predecessors) of the sf subgenre that HILOBROW was the first to name “semiopunk.”

BABEL (2022) | BABEL-17 (1966) | CAMP CONCENTRATION (1968) | A CANTICLE FOR LEIBOWITZ (1959) | CAT’S CRADLE (1963) | COSMONAUT KEEP (2000) | THE DIFFERENT GIRL (2013) | DOOM PATROL (1987–91) | THE EINSTEIN INTERSECTION (1967) | EMBASSYTOWN (2011) | ENGINE SUMMER (1979) | EXPLOITS AND OPINIONS OF DR. FAUSTROLL, PATAPHYSICIAN (1911) | FEERSUM ENDJINN (1994) | FLATLAND (1884) | FRIDAY (1982) | LE GARAGE HERMÉTIQUE (1976–79) | THE GLASS BEAD GAME (1943) | GLASSHOUSE (2006) | GRAVITY’S RAINBOW (1973) | THE HAMPDENSHIRE WONDER (1911) | LORD OF LIGHT (1967) | THE MAN WITH SIX SENSES (1927) | THE MOUNTAIN IN THE SEA (2022) | NINEFOX GAMBIT (2016) | ODD JOHN (1935) | PATTERN RECOGNITION (2003) | THE PLAYER OF GAMES (1988) | RIDDLEY WALKER (1980) | RODERICK (1980–83) | SNOW CRASH (1992) | THE SOFT MACHINE (1961) | SOLARIS (1961) | THE SPACE MERCHANTS (1953) | THE THREE STIGMATA OF PALMER ELDRITCH (1964) | TIME OUT OF JOINT (1959) | UBIK (1969) | VALIS (1981) | A VOYAGE TO ARCTURUS (1920) | VURT (1993) | WHITE NOISE (1985).

A VOYAGE TO ARCTURUS

David Lindsay’s Radium Age proto-sf/fantasy novel A Voyage to Arcturus (1920) features an adventurous Scot, Maskull, who encounters Krag, a semi-divine trickster figure. Krag whisks Maskull and another veteran, Nightspore, away to Tormance — an imaginary planet orbiting Arcturus. Departing from a deserted Scottish observatory in a crystalline “torpedo” piloted by Krag, our interstellar travelers make use of Arcturian “Back Rays,” by means of which light returns to its source. There is a strong whiff of Edgar Rice Burroughs in all this.

Tormance, however, turns out to be less an actual planet than a kind of proving-ground of the soul. Metaphysics meets surreal dream-quest here. Each chapter introduces a new philosophical system, religious idea, and concept of the true nature of the world. And then, having persuaded Maskull (and the reader) that we have finally discovered the meaning of life, the universe, and everything… the author mocks us for our belief. The opening scenes are atmospheric and exciting, in the vein of Wells; and the first few encounters on Tormance feel as though they are establishing important characters and a definitive trajectory. But no!

Tormance’s features include its alien sea, with water so dense that it can be walked on. Twin suns, floating trees and pillars of static lightning. Gnawl water is sufficient food to sustain life on its own. (The people of Poolingdred subsist entirely on gnawl water, because they can’t bear committing violence even against a leaf.) The local spectrum includes two primary colors unknown on Earth, and a third color, said to be compounded of one of the other two and blue. The sexuality of the Tormance species is ambiguous; Lindsay coined a new gender-neutral pronoun series, ae, aer, and aerself for the phaen — who are humanoid but formed of air.

There is also some proto-Fight Club stuff going on with Maskull and Nightspore, it transpires. And it’s just really weird. In Michael Moorcock’s description of the story:

Maskull’s hunt for Krag and Nightspore takes him across ethereal, ghastly dreamscapes where cruel men, loving women and intellectual monsters ponder the duality of God, the meaning of self-sacrifice, and the purpose of existence. His body creates and discards new sensory organs. An atmosphere of alienness is pervasive. A Buddhist paradise is followed by a world of degraded predators. Maskull, meeting what is perhaps God or perhaps the devil, senses a moral purpose to his journey, but that purpose remains mysterious. His inner debates are enhanced by the rapid pace, visual power and logic of the narrative.

Maskull, who has grown a tentacle from his heart and an organ called a breve, is tormented by Crystalman (also known as Surtur, or Shaping), who bedevils humankind with comforting illusions and false pleasures. (Is this God? Perhaps. Crystalman/God’s world is based on pleasure, which in fact destroys souls to feed himself. Krag/Satan is Pain. So… it’s hard to say that one is better than the other.)

As the story progresses, Maskull’s body develops a third arm, an extra eye, six extra eyes, and a forehead protrusion that allows him some degree of telepathy, among others. These mutations allow Maskull insight into the predominant philosophy of whatever land he is in.

Falseness, it transpires, is winning the war against truth; only Krag, who maintains his sense of humor, and who claims to be known on Earth as “Pain,” can hold his own in the fight. Maskull’s trials and tribulations release his authentic self, who must return to Earth and save more souls from Crystalman! Note that the book was also an influence on Philip Pullman’s His Dark Materials fantasy series.

A Voyage to Arcturus has been described as Calvinist (because pleasure is rejected in favor of instructive pain), Gnostic, Nietzschean, and psychedelic. There is romance and violence aplenty. It’s a fun saga, as Tolkien pointed out, even if you ignore all the philosophizing. Note that Lindsay, who grew up partly in Scotland, is a fan of such Scottish adventure writers as Walter Scott, Robert Louis Stevenson, and George MacDonald.

C.S. Lewis found the book “shattering, intolerable, and irresistible.” Of Lindsay, he’d claim: “He is the first writer to discover what ‘other planets’ are really good for in fiction… To construct plausible and moving ‘other worlds’ you must draw on the only real ‘other world’ we know, that of the spirit.” Hence Lewis’s own Perelandra sf series, not to mention the islands visited in his Narnia novel The Voyage of the Dawn Treader…. Moorcock mordantly notes: “Whatever the conventionally Christian CS Lewis learned from A Voyage to Arcturus for his Perelandra novels, he refused Lindsay’s commitment to the Absolute and lacked his God-questioning genius, the very qualities which give this strange book its compelling, almost mesmerising influence.”

Although the writing is clumsy and, at times, very stilted, Colin Wilson once called the book the “greatest novel of the twentieth century.” The brilliant and gnostic literary critic Harold Bloom, in his only attempt at fiction writing, wrote a sequel to this novel, entitled The Flight to Lucifer.

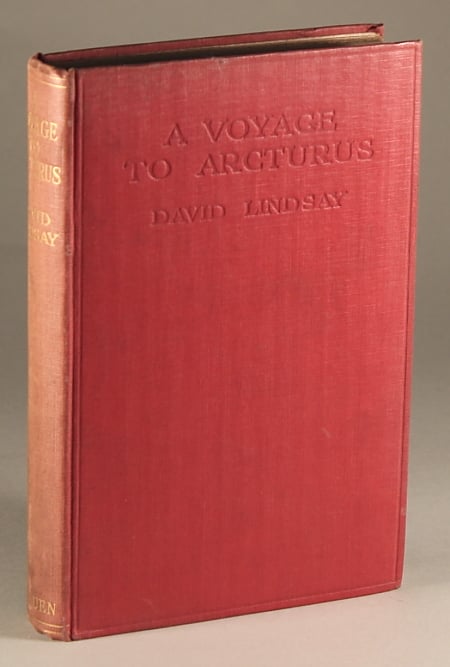

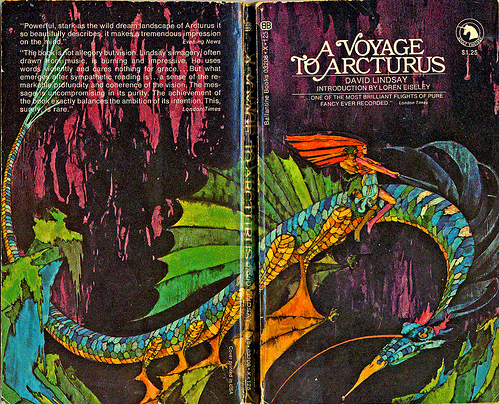

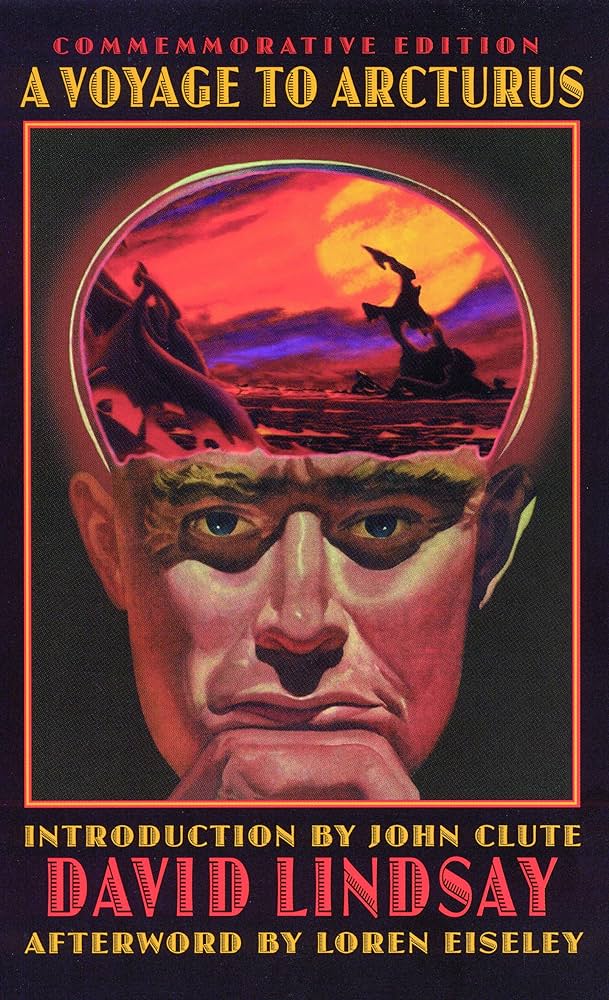

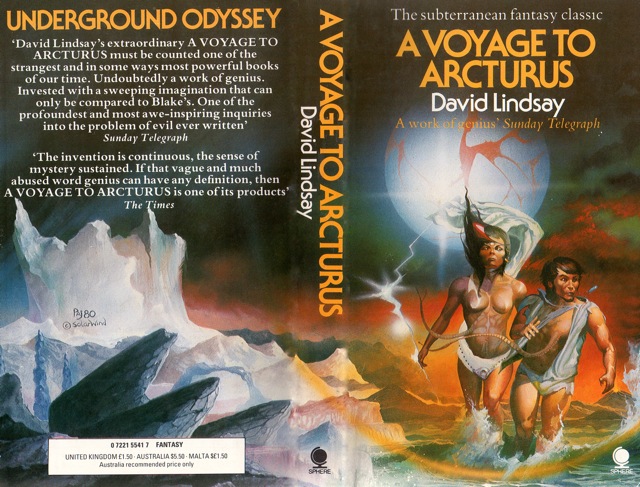

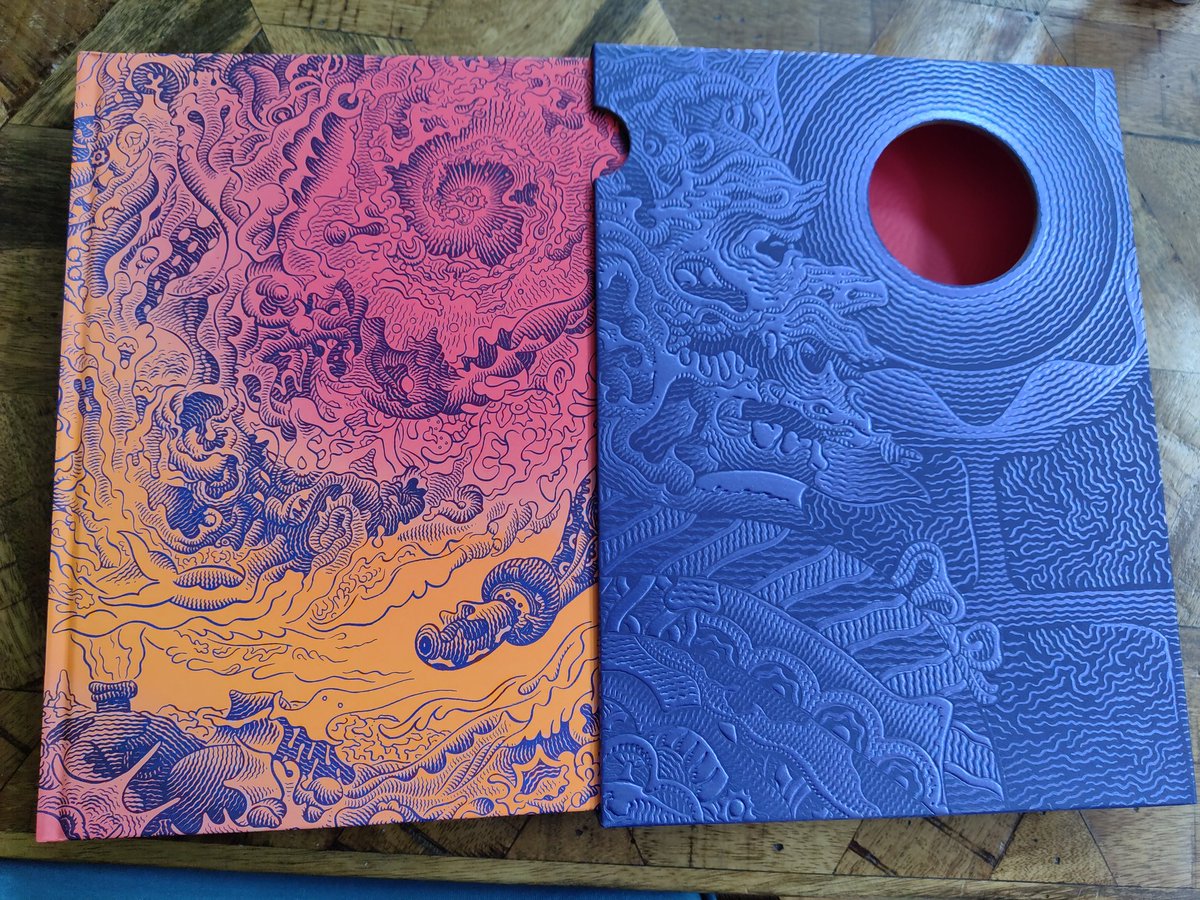

Methuen agreed to publish A Voyage to Arcturus, but only if Lindsay agreed to cut 15,000 words, which he did. These passages are assumed lost forever. On its first publication in 1920, it sold fewer than 600 copies. Ballantine Books’s influential Adult Fantasy series rescued the book from obscurity in 1968; and more recently, it was reissued by Bison Frontiers of Imagination. Alan Moore and John Clute have written introductions to recent editions.

JOSH GLENN’S *BEST ADVENTURES* LISTS: BEST 250 ADVENTURES OF THE 20TH CENTURY | 100 BEST OUGHTS ADVENTURES | 100 BEST RADIUM AGE (PROTO-)SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST TEENS ADVENTURES | 100 BEST TWENTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST THIRTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST GOLDEN AGE SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST FORTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST FIFTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST SIXTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST NEW WAVE SCI FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST SEVENTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST EIGHTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST DIAMOND AGE SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST NINETIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST HADRON AGE SCI-FI ADVENTURES.