SEMIOPUNK (4)

By:

September 24, 2023

An irregular, ongoing series of posts dedicated to surfacing examples (and predecessors) of the sf subgenre that HILOBROW was the first to name “semiopunk.”

BABEL (2022) | BABEL-17 (1966) | CAMP CONCENTRATION (1968) | A CANTICLE FOR LEIBOWITZ (1959) | CAT’S CRADLE (1963) | COSMONAUT KEEP (2000) | THE DIFFERENT GIRL (2013) | DOOM PATROL (1987–91) | THE EINSTEIN INTERSECTION (1967) | EMBASSYTOWN (2011) | ENGINE SUMMER (1979) | EXPLOITS AND OPINIONS OF DR. FAUSTROLL, PATAPHYSICIAN (1911) | FEERSUM ENDJINN (1994) | FLATLAND (1884) | FRIDAY (1982) | LE GARAGE HERMÉTIQUE (1976–79) | THE GLASS BEAD GAME (1943) | GLASSHOUSE (2006) | GRAVITY’S RAINBOW (1973) | THE HAMPDENSHIRE WONDER (1911) | LORD OF LIGHT (1967) | THE MAN WITH SIX SENSES (1927) | THE MOUNTAIN IN THE SEA (2022) | NINEFOX GAMBIT (2016) | ODD JOHN (1935) | PATTERN RECOGNITION (2003) | THE PLAYER OF GAMES (1988) | RIDDLEY WALKER (1980) | RODERICK (1980–83) | SNOW CRASH (1992) | THE SOFT MACHINE (1961) | SOLARIS (1961) | THE SPACE MERCHANTS (1953) | THE THREE STIGMATA OF PALMER ELDRITCH (1964) | TIME OUT OF JOINT (1959) | UBIK (1969) | VALIS (1981) | A VOYAGE TO ARCTURUS (1920) | VURT (1993) | WHITE NOISE (1985).

EXPLOITS AND OPINIONS OF DR. FAUSTROLL, PARAPHYSICIAN

Alfred Jarry’s proto-sf novella Gestes et opinions du docteur Faustroll pataphysicien: Roman néo-scientifique suivi de Spéculations (w. 1898, posthumously p. 1911) is a key text of ’pataphysique — Jarry’s “science of imaginary solutions,” i.e., a counter-inductive scientific methodology that is uniquely capable of making sense of anomalies (rather than seeking to explain them away) because it is constructed upon a metaphysics acknowledging the mutually constitutive identity of opposites.

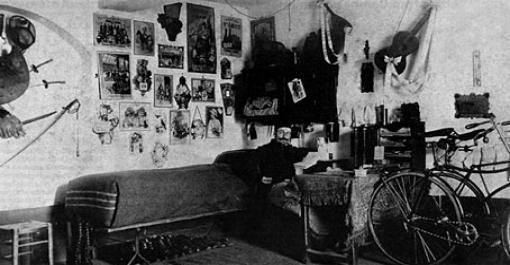

Author of the only convincing plan ever devised for the construction of a time machine, Jarry strikes me as himself being a visitor from a future in which religion, politics, violence, and other Ubu-esque social ills have been vanquished. (We can perhaps also infer that the bicycle is the primary means of urban transportation; and that people are shorter in stature.) Those whom Jarry has influenced — e.g., Apollinaire, Ionesco, Duchamp, Dick, Vian, the Situationists, Oulipo, Baudrillard — are ’pataphysical activists determined to realize Jarry’s noncoercive-utopian vision.

A brilliant scientist-inventor, Faustroll here sails around (an allegorical version of) Paris in an amphibious copper sieve-craft — whose construction was based on his insights into capillarity, surface tension, and equilateral hyperbolae. His copilot is the Wookiee-ish servant-creature Bosse-de-Nage; he is also accompanied by Panmuphle, a thuggish repo man seeking to collect on Faustroll’s debts. One might regard this as a Freudian trio — as per the diner scene in John Huston’s The Asphalt Jungle, say — since Panmuphle can certainly be said to represent society’s brutal commands, while Bosse-de-Nage is an instinctual creature. Faustroll is no deformed ego-stooge, however; he is calling the shots.

When Faustroll flees his creditors in his extraordinary, Batmobile-like “skiff,” he embarks upon a high-speed, slapstick, psychedelic metafictional odyssey which transports the crew from one fantasy island to another. Elsewhere, I’ve described this story a the missing link between the myth of Jason and the Argonauts and New Wave sci-fi of the ’60s and ’70s.

I imagine Faustroll resembling the author. He is smaller than his contemporaries; his hair and beard are startling. (Jarry describes Faustroll’s hair as alternately blond and black; his mustachios are green.) His skin-tight, space-suit-like costume is functional rather than decorative. He rides a bicycle everywhere, instead of driving. He fishes in the Seine for his dinner. Perhaps he carries a pistol. No doubt he speaks in Jarry’s herky-jerky way.

Near the book’s end, we learn that Dr. Faustroll possesses a kind of philosopher’s stone — a ring that allows him to transmute matter. The ring works in conjunction with a stone set inside his skull — which can be observed through a clear watchglass window. So perhaps he really is some kind of cyborg or enhanced human from the future. What is he doing here?

Faustroll’s crucial insight is that the virtual or imaginary nature of things as glimpsed by the heightened vision of far-out creative types, not to mention drug users, can be seized and lived as real. His scientific practice involves avidly pursuing such hypotheses; one imagines his laboratory as a shrine to far-out, imaginative world-building: science fiction, fantasy, comic books, the discoveries of psychonauts. Faustroll’s laboratory is the site of experiments with soap bubbles, gyrostats, and so forth. It’s a playful, non-sterile space. The fabric of reality is mutable, and Faustroll’s experiments are designed to allow him to perceive what he calls — borrowing the term from Vedic and Upanishadic texts — the Purusha, i.e., the unchanging and transcendent source of all that changes.

The only problem? Faustroll’s obsession with realizing the freaked-out fantasies of everyone from Coleridge, Mallarmé, and Beardsley to lesser-known poets and kooks has precluded his paying the rent on his laboratory. Panmuphle, a debt collector sent to kick Faustroll out of his lodgings, winds up shanghaied aboard the skiff when the scientist takes flight.

The year — in Jarry’s novel — is 1898. So when Panmpuphle seizes Faustroll’s possessions, the books in the scientist’s collection that he lists are fantastical works by Poe, Bloy, Lautréamont, Rimbaud, Verlaine, even Jarry. Each of these is a clue to the sort of adventure we’re about to embark upon.

Panmuphle shows up at the lab — not his first visit — to evict Faustroll once and for all. Faustroll gets him drunk and disoriented — he hurls Panmuphle into a wine cellar whose barrels have all been breached — then bundles him into his skiff. Because he needs a man with Panmpuphle’s abilities….

Faustroll’s “skiff,” which can not only glide atop water but along streets and straight up walls, is capable of carrying passengers across the barriers of the imagination itself. As such, it’s an ancestor of the Heart of Gold — the prototype ship, in The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy, that uses the Infinite Improbability Drive. To quote Karey Kirkpatrick, who with Douglas Adams adapted the novel for the screen in 2005, this ship is in fact a “plot contrivance machine”, making possible plotlines that would normally be too improbable to be believed.

Faustroll explains the nature of his research, and the capacities of his vehicle, to Panmuphle. He also shows him evidence of his explorations — objects he’s managed to snatch from the fantastic realms he’s visited so far. For example, the ancient mariner’s crossbow, from Coleridge’s poem; the prince’s eyeball poked out by a horse’s tail in The Thousand and One Nights; a scarab from Lautréamont’s Les Chants de Maldoror.

Bosse-de-Nage, meanwhile, is a hideous ape-like creature — his name means, more or less, “Buttocks Face” — who speaks in grunts only his master understands. (He is a comical Chewbacca or Groot character). Bosse-de-Nage carries the skiff through a secret passageway and deposits it upon the pavement of a back street in Paris. Panmuphle is locked into position — he’s a kind of oarsman — and off they go! Visuals become foggy, and there is a pervasive tearing sound, as the skiff leaves behind quotidian reality for various invented worlds.This is a revelatory and also hallucinatory, terrifying moment, for Panmuphle: He realizes, for the first time, that consensus reality is merely that which everyone has somehow consented to….

The skiff visits fourteen imaginary worlds. In some cases, Jarry is celebrating the imagination of artists or writers whom he admires; in other cases, he is mocking or criticizing someone’s world-building efforts. Each chapter is dedicated to the imaginative creator of this weird and wonderful, or terrible space. The picaresque nature of Faustroll’s exploits allows the novel to switch between genres. Although all of the adventures have an absurd, comical edge, some of them are sci-fi, or fantasy, or horror.

For example:

- The Isle of Cack in the Sea of Shit — inspired by Louis Libaude, a speculator in modern art who ruthlessly preyed on Jarry’s artist peers

- The Land of Lace — inspired by the English illustrator and author Aubrey Beardsley, whose ink drawings depicted the grotesque, the decadent, and the erotic.

- The Forest of Love — inspired by the Post-Impressionist painter and writer Emile Bernard.

- The Amorphous Isle — inspired by Franc-Nohain, the librtettist and poet who with Jarry co-founded the Théatre des Pantins, which in 1898 was the site of marionette performances of Jarry’s Ubu Roi. The inhabitants of this island remind me of Iain M. Banks’s Minds: sapient, hyperintelligent machines that have evolved, redesigned themselves, and become many times more intelligent than their original creators.

- The Fragrant Isle — inspired by Gauguin, an important figure in the Symbolist movement as a painter, sculptor, printmaker, ceramist, and writer.

- The Castle Errant — inspired by Gustave Kahn, the French Symbolist poet and art critic who may have invented the term vers libre, or free verse.

- The Isle of Ptyx — inspired by Mallarmé, the Symbolist poet whose work anticipated and inspired Cubism, Futurism, Dadaism, and Surrealism. Here, one can perceive the true substance of the universe, unmediated! (Mallarmé’s poem ‘Sonnet en yx’ posed a challenge to interpretation via the term ptyx: was this a nonsensical neologism or an untranslated derivation from another language? The term resonated with other artists, for whom it came to exemplify a kind of “word magic” that modernism conjures out of non-translation. [See the essay collection Modernism and Non-Translation]

- The Isle of Cyril — inspired by Marcel Schwob’s Imaginary Lives, an 1896 collection of semi-biographical short stories mixing known and fantastical elements. Here we encounter Captain Kidd — or Schwabb’s version of Kidd.

- The Great Church of Snoutfigs — inspired by Laurent Tailhade, the satirical poet, anarchist polemicist, and essayist. A Cthulhu-like horror show, involving a monster conjured up during a church service.

One could have a great deal of fun mapping out this meta-fictional voyage extraordinaire.

A third character now joins us. A merman, of sorts: Bishop Mendacious. This is “the Sea Bishop,” a marine monster in a bishop’s habit spotted in Poland in 1531; one pictures a malignant, religiously garbed version of Mike Mignola’s Abe Sapien character.

We also learn that Faustroll becomes uncontrollably murderous when he sees an image of a horse’s head. Bishop Mendacious reveals a horse-head sign to Faustroll, who winds up releasing a poisonous fog in Paris — and killing Bosse-de-Nage. There is an extended sequence in which the Bishop encounters a kind of Weeble — a man-shaped toilet paper holder, that rocks back and forth on a hemispherical base — and throws it down the toilet, then shits on top of it. Why? Not sure.

Bosse-de-Nage then reappears — somehow, he isn’t dead. Faustroll sets some sort of monstrous automatic painting machine into motion. Kinda like Damien Hirst’s “spin painting” device, only this one occasionally creates great works of art. Faustroll sleeps with the Bishop’s daughter. There’s a kind of apocalyptic ending. Faustroll and Panmuphle die — but they don’t really die. Instead, they dissolve into what Faustroll calls “Aethernity.”

What’s the point of it all? The scientific method begins with precise observations of nature, conducted by a cautious researcher who has bracketed his imagination and blinkered his perspective; eventually, it results in a law or theory. Faustroll instead embraces multiple perspectives, no matter how absurd they may seem — and recognizes no laws. Like the character Lance in Francis Ford Coppola’s Apocalypse Now amid the chaos of life Jarry surfs what William James was the first to describe as the “stream of consciousness.”

JOSH GLENN’S *BEST ADVENTURES* LISTS: BEST 250 ADVENTURES OF THE 20TH CENTURY | 100 BEST OUGHTS ADVENTURES | 100 BEST RADIUM AGE (PROTO-)SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST TEENS ADVENTURES | 100 BEST TWENTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST THIRTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST GOLDEN AGE SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST FORTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST FIFTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST SIXTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST NEW WAVE SCI FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST SEVENTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST EIGHTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST DIAMOND AGE SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST NINETIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST HADRON AGE SCI-FI ADVENTURES.