RADIUM AGE UPDATE

By:

August 10, 2023

HILOBROW’s Josh Glenn is founding editor of the MIT Press’s RADIUM AGE series of reissued proto-sf novels and stories. Today, Foreword‘s THIS WEEK newsletter published an interview with Josh about the series.

Excerpt:

I’m an enthusiastic reader of early 20th century authors — from Henry James to Dorothy L. Sayers, and from E. Nesbit to Robert E. Howard. So one thing that demands saying about proto-science fiction (that is, speculative fiction published after the scientific romances of Wells and Verne, and mostly before the term “science fiction” existed) is that quite a lot of it is terrifically well-written, smart, and entertaining. This came as a surprise to me, since genre historians have typically suggested that any sf before the so-called Campbell Revolution of the mid-1930s on isn’t worth reading!

Here are a few other things going on with the RADIUM AGE project this month, so far…

By the end of August, the RADIUM AGE series will have published the following three titles.

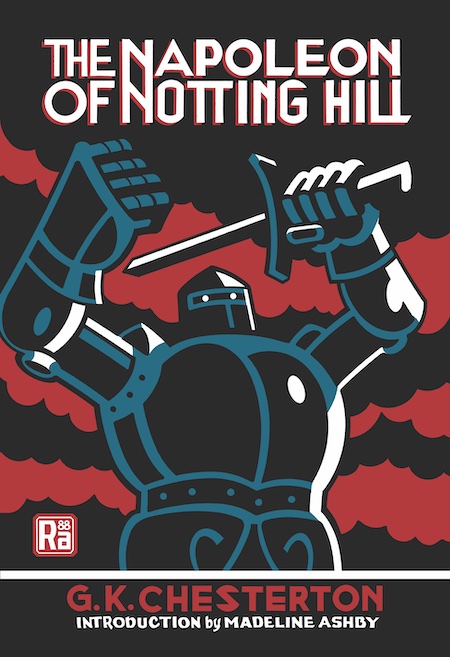

G.K. CHESTERTON

Introduction by MADELINE ASHBY

(August 1, 2023)

When Auberon Quin, a prankster nostalgic for Merrie Olde England, becomes king of that country in 1984, he mandates that each of London’s neighborhoods become an independent state, complete with unique local costumes. Everyone goes along with the conceit until young Adam Wayne, a born military tactician, takes the game too seriously… and becomes the Napoleon of Notting Hill. War ensues throughout the city — fought with sword and halberd!

“A vastly entertaining book, which should be breathlessly enjoyed at Notting Hill and elsewhere.” — Daily Chronicle (1904)

“Whimsically expressed criticism… with a suspicion of gallimaufry and hints of the cap-and-bells here and there.” — New York Times (1904)

“As irresponsibly ludicrous as a modern burlesque, as quaintly serious, at last, as a medieval morality.” — The Bookman (May 1904)

“More modern than the moderns, more medieval than the medievalists, funnier than all of them — reading Chesterton today is like watching someone give a speech of unimpeachable common sense from the bridge of a departing UFO.” — Atlantic columnist James Parker

Press for MITP’s edition of The Napoleon of Notting Hill includes the following…

“Unquestionably a satirical masterpiece.” — Michael D. Gordin, Los Angeles Review of Books

MADELINE ASHBY is a consulting futurist and science fiction writer based in Toronto. She is the author of the Machine Dynasty series, Company Town, and contributor to How to Future: Leading and Sense-making in an Age of Hyperchange. She has developed science fiction prototypes for Changeist, the Institute for the Future, the Smithsonian Institution, SciFutures, Nesta, The World Health Organization, the World Bank, the Atlantic Council, and others. Her work has appeared in BoingBoing, Slate, MIT Technology Review, WIRED, and elsewhere.

G.K. CHESTERTON (1874–1936) was an English author, poet, critic, and newspaper columnist known for his brilliant, epigrammatic paradoxes. His best-known character is the priest-detective Father Brown, featured in over 50 stories published between 1910–1936, who solves mysteries and crimes thanks to his understanding of spiritual and philosophic truths; and his best-known novel is The Man Who Was Thursday (1908), a metaphysical thriller. In addition to The Napoleon of Notting Hill, his first novel, he wrote several other near-future satires of England.

Originally published in 1904. Cover designed by Seth. See this book at The MIT Press.

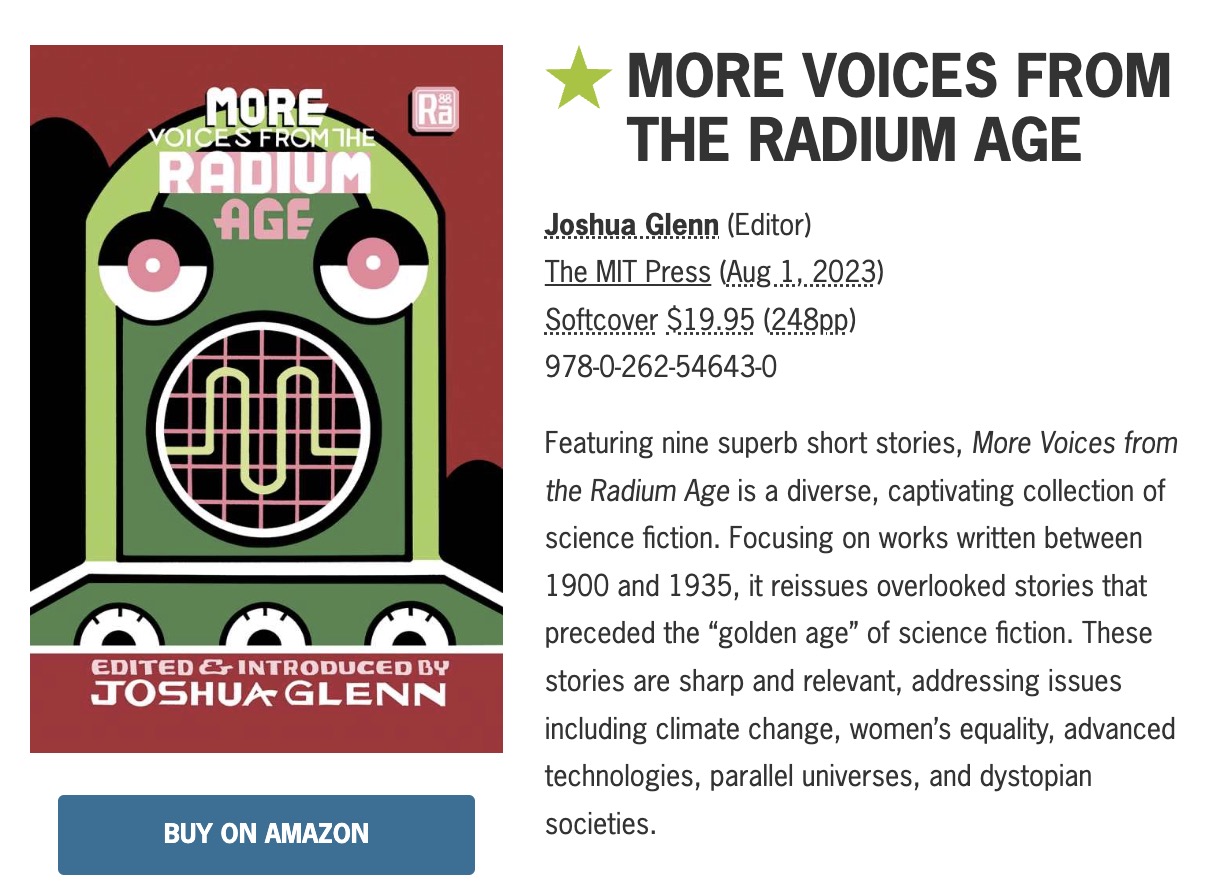

EDITED BY JOSHUA GLENN

Introduction by JOSHUA GLENN

(August 1, 2023)

A planetary escape pod, an alien body-snatcher, an underground Alaskan city, and a war between the sexes in Atlantis! These are just a few of the outré elements you’ll find in More Voices from the Radium Age, a showcase of proto–science fiction edited and introduced by Joshua Glenn. This volume brings together well-known and lesser-known writers in an inclusive collection that features E. Nesbit and May Sinclair, two of the genre’s first female writers.

More Voices from the Radium Age also introduces readers to writers who have fallen into obscurity, including proto–sf pioneer George C. Wallis, the Russian Symbolist Valery Bryusov, and “weird” horror master Algernon Blackwood. It also includes H.G. Wells, who continued to make startling predictions in the early 20th century, and Abraham Merritt and George Allan England, two of the biggest names in the era of the pulp scientific romance.

An essential collection for any sci fi fan, More Voices from the Radium Age is a wild and darkly cathartic ride through the anxieties, fantasies, and nightmares that ultimately shaped the genre we now know as science fiction.

Press for More Voices from the Radium Age includes the following…

“A diverse, captivating collection… highlighting neglected voices in speculative and science fiction.” — Foreword (starred review)

“Add [it] to your August Reading List.” — Gizmodo

JOSHUA GLENN is a consulting semiotician and editor of the websites HiLobrow and Semiovox. The first to describe 1900–1935 as science fiction’s “Radium Age,” he is editor of the MIT Press’s series of reissued proto-sf stories from that period. He is coauthor and co-editor of various books including the family activities guide UNBORED (2012), The Adventurer’s Glossary (2021), and Lost Objects (2022). In the 1990s, he published the indie intellectual journal Hermenaut.

ALGERNON BLACKWOOD (1869–1951) is best known as the author of supernatural fiction with cosmic aspirations — including The Centaur (1911), Julius LeVallon (1916), and The Bright Messenger (1921), as well as stories like “The Willows” (1907) and “The Wendigo” (1910). The English author’s best-known horror stories, and his series of stories featuring the occult detective John Silence, seek less to frighten than to induce a sense of awe. His work was a significant influence on H.P. Lovecraft and his circle.

VALERY BRYUSOV (1873–1924), a poet, dramatist, art critic, and historian, was one of the principal members of the Russian Symbolist movement. He anticipated giant domed computerized cities, ecological catastrophe, and a totalitarian state in his 1907 story collection Zemnaya Os (Earth’s Axis), published in English as The Republic of the Southern Cross (1918, translator unknown). Though many of his fellow Symbolists fled the country after the Russian Revolution of 1917, Bryusov remained until his death.

GEORGE ALLAN ENGLAND (1877–1936) was an American writer and explorer, best known for proto sf-novels including the Darkness and Dawn Series (1912–1914), as well as The Elixir of Hate (1910), The Empire in the Air (1914), and The Air Trust (1915). Like some other proto-sf writers of the era, he was anti-capitalist; in 1912 he ran for Governor of Maine as the Socialist Party of America’s candidate. His story “The Thing from—’Outside'” appeared in Hugo Gernsback’s magazine Science and Invention.

ABRAHAM MERRITT (1884–1943), who wrote as A. Merritt, was one of the most successful and influential proto-sf writers of the pulp era. He is best remembered today for his novels The Moon Pool (1919), The Ship of Ishtar (1924), The Face in the Abyss (1931), and Dwellers in the Mirage (1932). His stories’ suggestion that lost races, ancient technologies, and other far-out phenomena were waiting to be discovered beneath the surface of everyday modern life were a major influence on subsequent sf and fantasy.

EDITH NESBIT (1858–1924) was an English author best remembered today for her fantasies for children — written as E. Nesbit, they include The Wouldbegoods (1901) and Five Children and It (1902) — which have directly influenced everyone from C.S. Lewis and Diana Wynne Jones to J.K. Rowling. In addition to essentially inventing the children’s fantasy adventure as we know it, she was author of horror, supernatural, and proto-sf stories. A political activist, she co-founded Britain’s socialist Fabian Society.

MAY SINCLAIR was the pseudonym of English author and suffragist Mary Amelia St. Clair (1863–1946). She is best remembered for semi-autobiographical novels such as Life and Death of Harriett Frean (1922). Sinclair’s supernatural and proto-sf tales, which would find champions in T.S. Eliot and Jorge Luis Borges, explore her idiosyncratic take on the idealist notion that reality is a mental construct closely connected to ideas; they were also influenced by contemporary mathematical theories of hyperspace.

BOOTH TARKINGTON (1869–1946) was an American author best remembered for The Magnificent Ambersons (1918) and Alice Adams (1921), both of which won the Pulitzer Prize; as well as for Penrod (1914), a collection of comic sketches about the titular 11-year-old boy, and its many sequels. In the 1910s and 1920s he was considered to be America’s greatest living author, as important as Mark Twain; today, he is forgotten. An admirer of Charles Fort, Tarkington’s only sf story is “The Veiled Feminists of Atlantis.”

GEORGE C. WALLIS (1871–1956) began writing scientific romances in the 1890s. Early stories of interest, besides “The Last Days of Earth,” include “The White Queen of Atlantis” (1896), “The Great Sacrifice” (1903), and “In Trackless Space” (1904). His novel Beyond the Hills of Mist (serialized 1912) concerns a Tibetan lost race that plans world domination; and his last sf novel, The Call of Peter Gaskell, appeared in 1948. He is most likely the only Victorian-era sf writer to continue to publish after World War Two.

H.G. WELLS (1866–1946) is best known today as author of pioneering scientific romances such as The Time Machine (1895), The Island of Doctor Moreau (1896), The Invisible Man (1897), and The War of the Worlds (1898). An important influence on sf authors from Olaf Stapledon to Arthur C. Clarke, the prodigious English writer was also a social critic and futurist who penned dozens of novels, stories, and works of history and social commentary — in which he proposed more rational ways to organize society.

Cover designed by Seth. See this book at The MIT Press.

(ABRIDGED EDITION)

WILLIAM HOPE HODGSON

Introduction by ERIK DAVIS

(August 15, 2023)

In the far future, humankind’s survivors huddle below the Earth’s frozen surface in a pyramidal fortress-city that, for centuries now, has been under siege by loathsome “ab-humans,” enormous slugs and spiders, and malevolent “watching things” from another dimension. When our unnamed protagonist receives a telepathic distress signal from a woman whom (in a previous incarnation) he’d once loved, he sallies forth on an ill-advised rescue mission — into the fiend-haunted Night Land!

“One of the most potent pieces of macabre imagination ever written.” — H.P. Lovecraft, “Supernatural Horror in Literature” (1927).

“The author’s […] descriptions of the outer darkness of the eternal night and the horrors abounding therein produce a weird and fantastic impression.” — The Athenaeum (May 4, 1912)

“The most touching, exquisite spirit romance that has ever been written.” — The Bookman (July 1912)

“In all literature, there are few works so sheerly remarkable, so purely creative, as The Night Land… Only a great poet could have conceived and written this story; and it is perhaps not illegitimate to wonder how much of actual prophecy may have been mingled with the poesy… It is to be hoped that work of such unusual power will eventually win the attention and fame to which it is entitled.” — Clark Ashton Smith, “In Appreciation of William Hope Hodgson” (1944)

“[Good science fiction stories] give, like certain rare dreams, sensations we never had before, and enlarge our conception of the range of possible experience… W.H. Hodgson’s The Night Land [makes the grade] in eminence from the unforgettable sombre splendour of the images it presents…” — C.S. Lewis, “On Science Fiction” (1955)

“For all its flaws and idiosyncracies, The Night Land is utterly unsurpassed, unique, astounding. A mutant vision like nothing else there has ever been.” — China Miéville

Press for MITP’s edition of The Night Land includes the following…

“The most extreme inquiry into human dependence on technology in the face of a nature perpetually degenerating into monstrosity and entropic heat death.” And: “Hodgson was clearly an inspiration for generations of writers such as H. P. Lovecraft, who learned a thing or two about hideous monsters from texts like this one.” — Michael D. Gordin, Los Angeles Review of Books

ERIK DAVIS is an author, teacher, and award-winning journalist based in San Francisco. His publications include High Weirdness: Drugs, Esoterica, and Visionary Experience in the Seventies, Nomad Codes, and the cult classic Techgnosis: Myth, Magic, and Mysticism in the Age of Information. Davis earned his PhD in religious studies from Rice University, and currently teaches at Pacifica Graduate Institute. He writes the Substack publication Burning Shore, and has completed a history of LSD blotter art for MIT Press.

WILLIAM HOPE HODGSON (1877–1918) was an English poet, sailor, bodybuilder, and weird fiction pioneer whose horror, fantastic, and proto-sf novels — in addition to The Night Land — include The Boats of the “Glen Carrig” (1907), The House on the Borderland (1908), and The Ghost Pirates (1909). He also wrote stories in the Sargasso Sea series, the Captain Gault series, and a series about the occult detective Carnacki.

Originally published in 1912. Cover designed by Seth. See this book at The MIT Press.

During August so far, the series has received the following publicity.

- Coinciding closely with the book’s August 1 publication date, the Boston Globe‘s IDEAS section ran excerpts from three stories collected in MORE VOICES FROM THE RADIUM AGE, along with some contextualizing remarks from the book’s editor, Josh Glenn. Excerpt:

Well before I dubbed the era science fiction’s “Radium Age,” I was a fan of A. Merritt, Rose Macaulay, Olaf Stapledon, Charlotte Perkins Gilman, and other future-focused speculative authors of the period. I enjoy the fact that, while it’s less naively optimistic than the Victorian-era “scientific romances” of H.G. Wells, Jules Verne, and their ilk, at the same time this body of literature offers a welcome antidote to the wised-up “realism” of Isaac Asimov, Robert Heinlein, and other avatars of science fiction’s so-called Golden Age, when it comes to such outré visions as the detoxification of masculinity, say, or the greenifying of cities, or the forced appropriation of the surplus value created by workers.

- Josh was interviewed by the prolific sf magazine editor and writer Arley Sorg for the August issue of the sf/f magazine Clarkesworld. Excerpt:

J. J. Connington’s Nordenholt’s Million is a disturbing reminder that tycoons with fascist ambitions are quite adept at stoking our fears and seizing upon emergency situations. Pauline Hopkins’ Of One Blood (first published in Boston’s The Colored American Magazine in 1902–1903) was recently singled out by Adam Bradley, founding director of the Laboratory for Race & Popular Culture at UCLA, as one of the key books that “help to tell a story of Black American literature that reflects the infinite number of ways of being Black in America — and of being in the world.” J.D. Beresford’s A World of Women and Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage warned us — long before the Supreme Court’s Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization decision — that we shouldn’t take women’s hard-won rights for granted.

- “Add [it] to your August Reading List.” — on August 2, Gizmodo included More Voices in their roundup of recommended sf story collections.

- On August 4, the literary website LitHub published “Problems Plus Time: What Creates a Dystopia, Real or Imagined,” Madeline Ashby’s introduction to the RADIUM AGE series’ edition of G.K. Chesterton’s The Napoleon of Notting Hill. Excerpt:

Writing this novel in 1904, a scant few years before revolutions in Russia, Mexico, and Ireland, and ten years before the Great War, Chesterton would have the science fiction writer’s queasy-making experience of watching certain fictions pass into reality—in his case, the collapse of traditional power structures. In fact, the book may have helped inspire a revolution closer to home: Michael Collins, director of intelligence for the Irish Republican Army during the 1919–1921 War of Independence, was a lifelong fan of The Napoleon of Notting Hill—owing to its anti-imperialist theme and its vivid depiction of urban guerilla warfare.

- On August 7, LitHub published a version of Josh’s introduction to More Voices from the Radium Age. The piece was titled “How Scientific and Technological Breakthroughs Created a New Kind of Fiction: Joshua Glenn Chronicles the Development of Sci-Fi in the Early 20th Century.” Excerpt:

“The man of science must have been sleepy indeed,” as the author of The Education of Henry Adams would recall, “who did not jump from his chair like a scared dog when, in 1898, Mme. Curie threw on his desk the metaphysical bomb she called radium.”

What Frederick Soddy, the English radiochemist whose lectures would inspire H. G. Wells to predict the atomic bomb, described as the “ultra-potentialities” of radioactive elements seemed limitless. Throughout the nineteen-aughts and -tens, scientists and snake-oil salesmen alike would ascribe to radium — and radiation in general — vitalizing, even life-giving powers. By the 1920s, then, the Soviet biochemist Alexander Oparin and the English biologist J. B. S. Haldane could independently propose that radiation, acting upon our planet’s inorganic compounds billions of years ago, had produced a primordial “soup” from which emerged life.

Science fiction, too, emerged during the genre’s 1900–1935 Radium Age from out of a hot dilute soup of sorts, this one composed of outré genres of literature — from occult mysteries and paranormal thrillers to Yukon adventures and Symbolist poetry — acted upon by the energy of new scientific and technological theories and breakthroughs.

Stay tuned for more updates…

MORE RADIUM AGE SCI FI ON HILOBROW: RADIUM AGE SERIES from THE MIT PRESS: In-depth info on each book in the series; a sneak peek at what’s coming in the months ahead; the secret identity of the series’ advisory panel; and more. | RADIUM AGE: TIMELINE: Notes on proto-sf publications and related events from 1900–1935. | RADIUM AGE POETRY: Proto-sf and science-related poetry from 1900–1935. | RADIUM AGE 100: A list (now somewhat outdated) of Josh’s 100 favorite proto-sf novels from the genre’s emergent Radium Age | SISTERS OF THE RADIUM AGE: A resource compiled by Lisa Yaszek.