SEMIOPUNK (1)

By:

August 3, 2023

An irregular, ongoing series of posts dedicated to surfacing examples (and predecessors) of the sf subgenre that HILOBROW was the first to name “semiopunk.”

BABEL (2022) | BABEL-17 (1966) | CAMP CONCENTRATION (1968) | A CANTICLE FOR LEIBOWITZ (1959) | CAT’S CRADLE (1963) | COSMONAUT KEEP (2000) | THE DIFFERENT GIRL (2013) | DOOM PATROL (1987–91) | THE EINSTEIN INTERSECTION (1967) | EMBASSYTOWN (2011) | ENGINE SUMMER (1979) | EXPLOITS AND OPINIONS OF DR. FAUSTROLL, PATAPHYSICIAN (1911) | FEERSUM ENDJINN (1994) | FLATLAND (1884) | FRIDAY (1982) | LE GARAGE HERMÉTIQUE (1976–79) | THE GLASS BEAD GAME (1943) | GLASSHOUSE (2006) | GRAVITY’S RAINBOW (1973) | THE HAMPDENSHIRE WONDER (1911) | LORD OF LIGHT (1967) | THE MAN WITH SIX SENSES (1927) | THE MOUNTAIN IN THE SEA (2022) | NINEFOX GAMBIT (2016) | ODD JOHN (1935) | PATTERN RECOGNITION (2003) | THE PLAYER OF GAMES (1988) | RIDDLEY WALKER (1980) | RODERICK (1980–83) | SNOW CRASH (1992) | THE SOFT MACHINE (1961) | SOLARIS (1961) | THE SPACE MERCHANTS (1953) | THE THREE STIGMATA OF PALMER ELDRITCH (1964) | TIME OUT OF JOINT (1959) | UBIK (1969) | VALIS (1981) | A VOYAGE TO ARCTURUS (1920) | VURT (1993) | WHITE NOISE (1985).

THE GLASS BEAD GAME

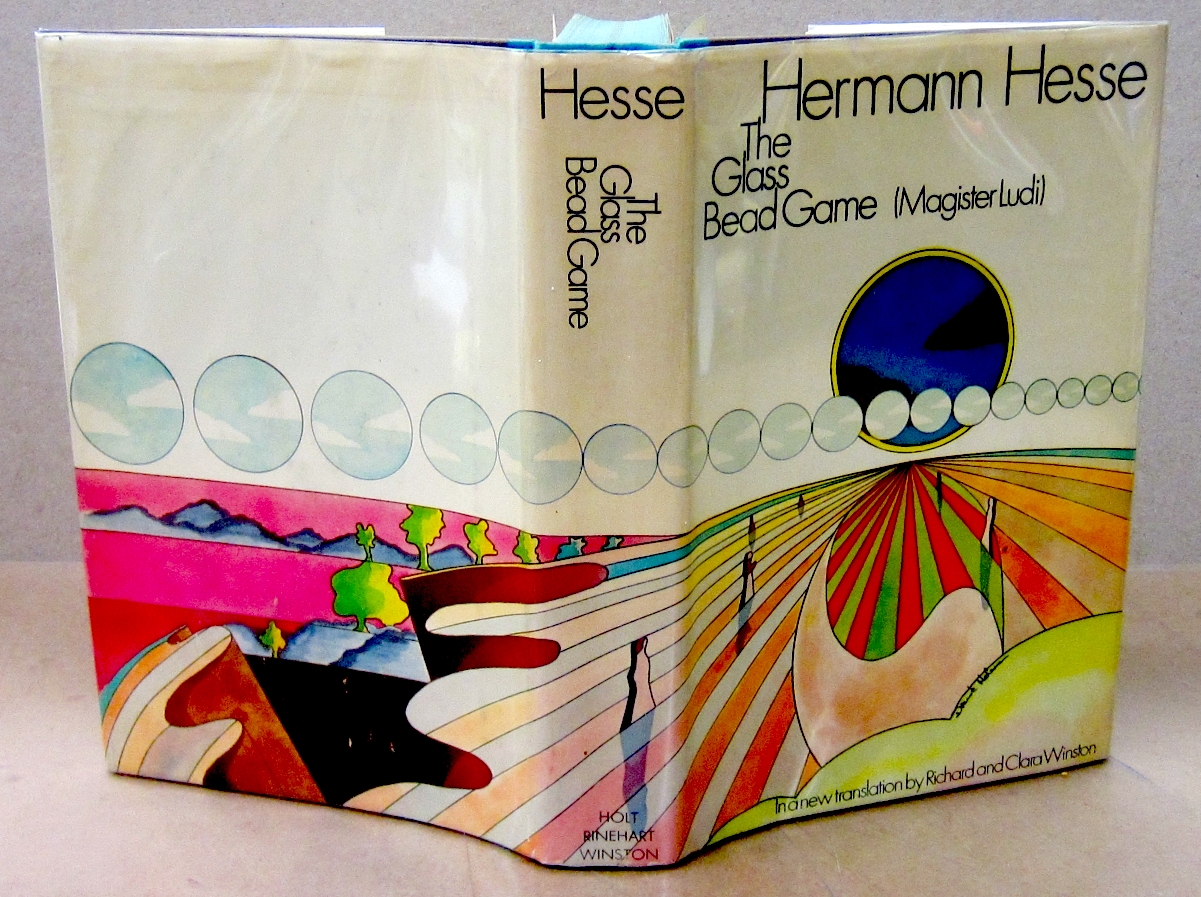

The Glass Bead Game (1943, Der Glasperlenspiel; also published as Magister Ludi) is the last full-length novel by the German author Hermann Hesse, and is widely regarded as the culmination of his career. Set in a post-catastrophic, ambiguously utopian twenty-fifth century (after “the shocks of the last great epoch of wars”), it was begun in 1932 (in Zurich, shortly before Hesse moved to Montagnola), and fragments of the novel appeared in literary journals before it was published in book form. So let’s count it as a work of Radium Age science fiction.

The novel imagines an intentional community and Argonaut Folly (Castalia) whose members are dedicated to studying all Eastern and Western arts and scholarship — in order to dialectically synthesize them in a complex game. It is a mode or means of playing with the totality of a culture’s insights, ideas, and values, each of which is symbolized by a glass bead; these beads are then organized, by means of stringing them on an abacus-like framework, into patterns which — to the game’s players — are greatly significant. The goal of each individual game is to compete in developing “themes” much like a piece of classical music does. The game’s players are intellectual-artistic supermen, if you will; an elite few who have been selected and trained for this purpose from an early age. They are a kind of Baudelairean/Nietzschean aristocracy — not of birth, but of talent.

The novel purports to be the work of a narrator who has assembled various manuscripts concerning Josef Knecht, who becomes the Master of the Glass Bead Game, and whose life is narrated in the novel. (From certain comments it seems that the narrator is himself a former pupil of Knecht and a player of the Glass Bead Game.) The narrator describes the course of Knecht’s life as “a circle, or an ellipse or spiral or whatever, but certainly not a straight line,” which suggests to this spiral/ellipse-sensitive reader, at least, that we would perhaps also be useful to our analysis if we thought of The Glass Bead Game as a ’pataphysical novel.

And of course, I’m also here to offer Hesse’s novel as an important early-ish example of the sf subgenre that this series asks you think of as semiopunk. (Matthew Battles proposed this fun neologism, via Instagram, upon reading my 2020 story/excerpt “Validation Session.”)

What is the Glass Bead Game? We don’t know, exactly… nor can we know, since like all anti-anti-utopian literature (to borrow a utopian-theory concept from Fredric Jameson), The Glass Bead Game posits a novum that is unrepresentable, at least in certain critical respects, to those of us still in a pre-utopian state. The game is a game, played by game-players… but it is also an epistemological exercise that draws its most expert players “into the center, the mystery and innermost heart of the world, into primal knowledge.” The game is about what things mean… and how they mean what they mean. How things mean what they mean turns out to have something to do with elegant, thrilling patterns; the game is a “dynamic phenomenon” comprehended in “an image of rhythmic processes,” a difficult and rewarding exercise in deconstruction and decoding, pattern recognition, and patterning. The result might be thought of as a “G[lasperlenspiel]-schema.”

Players of this game must be deeply well-versed in all the arts and sciences, as well in religious and philosophical concepts, in order to comprehend and communicate in its “sacred and divine language.” Scholars with a too-narrow purview need not apply, though the players must be deeply familiar with all sorts of scholarship.

In a 1944 letter to Rolf Hoerschelmann, who’d asked about the novel, Hesse replied that “The Glass Bead Game is a language, a complete system; it can be played in every manner conceivable, by one person improvising, by several people in a structured way, competitively and also hieratically.” By “hieratically,” he appears to mean: In the manner of one interpreting an esoteric sacred text. There is a neo-Platonic subtext here; a sense that the philosopher’s mission is to surface and dimensionalize his culture’s latent, tacit, unspoken norms and forms. For those of us who suspect that Plato’s Republic is itself an ambiguous utopia, we’re also led to wonder whether a social order directed by philosophers engaged in meditative scholarliness is utopian.

All of which sounds way too earnest for a game, which is supposed to be fun… which is why it’s important to note that, for Hesse, playing the Glass Bead Game transcends the earnest/fun dichotomy. The game’s players understand that while earnestness may be the opposite of light-heartedness, seriousness is not. It’s been pointed out that Schiller’s 1795 treatise On the Aesthetic Education of Mankind is surely a key literary intertext for Hesse’s novel. Here, Schiller articulates (for the first time?) a high-lowbrow ideal according to which “the most frivolous theme must be so treated that it leaves us ready to proceed directly from it to some matter of the utmost import,” and conversely, “the most serious material must be so treated that we remain capable of exchanging it forthwith for the lightest play.”

Hesse, who’d predicted that the Weimar Republic would collapse in the face of totalitarian ideologies, had in the early 1930s started to conceive of a utopian alternative: Castalia, with its monastic order of highly skilled educators who have a civilizing influence on a future society. The book is dedicated to the Morgenlandfahrer, a reference to Hesse’s Die Morgenlandfahrt (Journey to the East, 1932), which depicts a league of like-minded travelers in time and space who pursue their common ideals in a quest — troubled by self-doubt, lack of courage, and worldly distractions.

Knecht is confronted with similar difficulties. He comes to realize that the Glass Bead Game can lead to empty virtuosity, to the egotistic satisfaction of artistic vanity, to ambitiousness, and to the acquisition and misuse of power. “Truth is lived, not taught,” he comes to understand. The abstract dimension in which the Game-players spend their waking hours is less valuable, in the end, than — for all its chaos, misery, and stupidity — the real world from which they’d worked so assiduously to free themselves.

Is it possible to renew and redeem the Glass Bead Game, by removing it from its austere context and making it… liveable? There’s a hint, at the novel’s end, that a wayward, strong-willed, nature-loving young pupil, son of Knecht’s longtime friend Designori, who’s argued from the beginning that Castalia is an “ivory tower” with no impact on the real world, may (literally) assume Knecht’s mantle.

JOSH GLENN’S *BEST ADVENTURES* LISTS: BEST 250 ADVENTURES OF THE 20TH CENTURY | 100 BEST OUGHTS ADVENTURES | 100 BEST RADIUM AGE (PROTO-)SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST TEENS ADVENTURES | 100 BEST TWENTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST THIRTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST GOLDEN AGE SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST FORTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST FIFTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST SIXTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST NEW WAVE SCI FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST SEVENTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST EIGHTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST DIAMOND AGE SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST NINETIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST HADRON AGE SCI-FI ADVENTURES.