POST-MICKEY MICE (3)

By:

June 7, 2023

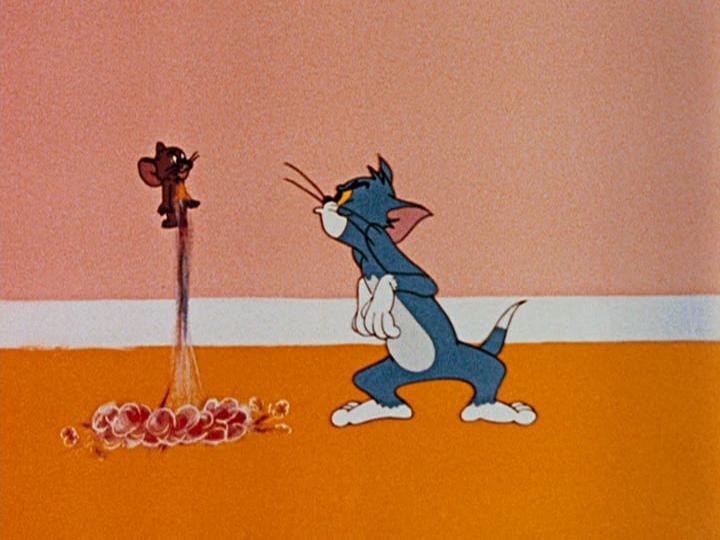

From the 1962 Tom & Jerry short Mouse Into Space.

An episode of MOUSE, a multi-part installment in the ongoing BESTIARY series.

During 2021–2022, I contributed three BESTIARY series installments, for each of which I conducted research into and offered a top-line analysis of 20th-century pop-culture depictions of a charismatic creature: OWL | BEAVER | FROG. I first developed this approach for an earlier series, TAKING THE MICKEY, which analyzes Mickey Mouse’s evolving significance. Via this new BESTIARY installment, I’ll “read” Mickey within the context of his fellow pop-culture mice.

This multipart BESTIARY series installment, collectively titled MOUSE, is divided up as follows: MOUSE (INTRO) | PRE-MICKEY MICE (1904–1913) | PRE-MICKEY MICE (1914–1923) | PRE-& POST-MICKEY MICE (1924–1933) | POST-MICKEY MICE (1934–1943) | POST-MICKEY MICE (1944–1953) | POST-MICKEY MICE (1954–1963) | POST-MICKEY MICE (1964–1973) | POST-MICKEY MICE (1974–1983) | POST-MICKEY MICE (1984–1993) | POST-MICKEY MICE (1994–2003).

(1954–1963)

According to HILOBROW’s periodization scheme, the cultural era known as the nineteen-fifties begins c. 1954 and ends c. 1963. During this period, let’s see how the mice tropes — surfaced via this audit, and dimensionalized in the series’ introduction — shake out via pop culture.

In a 1953 interview, Walt Disney would lament, “Mickey’s our problem child. He’s so much of an institution that we’re limited in what we can do with him. If we have Mickey kicking someone in the pants we get a million letters from mothers telling us we’re giving their kids the wrong ideas. Mickey must always be sweet, always lovable. What can you do with such a leading man?”

In a 1989 Journal of Popular Culture essay on “The Masks of Mickey Mouse,” Robert W. Brockway would answer Walt’s question:

During the mid-fifties, as the genial host of Disneyland in tails, Mickey… climbed to the top of the Disney corporate empire as the corporate image. This was his most recent metamorphosis. The middle-aged Mickey mirrors the world of the corporate executive. He became an ‘organization man.’ He also became the king of the Magic Kingdom and his appearances took on the mystique of monarchy.

It’s this 1954–1963 version of Mickey that we’ll see critiqued savagely in this series installment (NB: Adorno’s prescient critique, noted in this series’ previous installment, anticipates this backlash.)

The Fifties (1954–1963, according to HILOBROW’s periodization schema) is known today as the Golden Age of television. In 1954, Walt Disney helped get things started by selling the company’s first TV show — Walt Disney’s Disneyland — to ABC. Disney used the show to unveil Disneyland. The theme park would open in Anaheim, California in 1955.

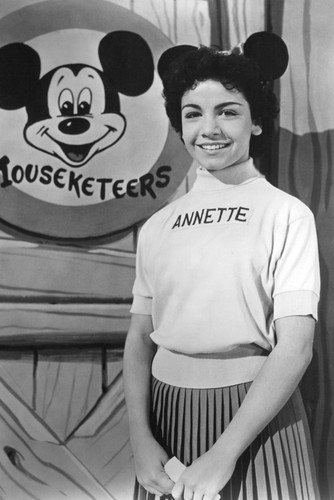

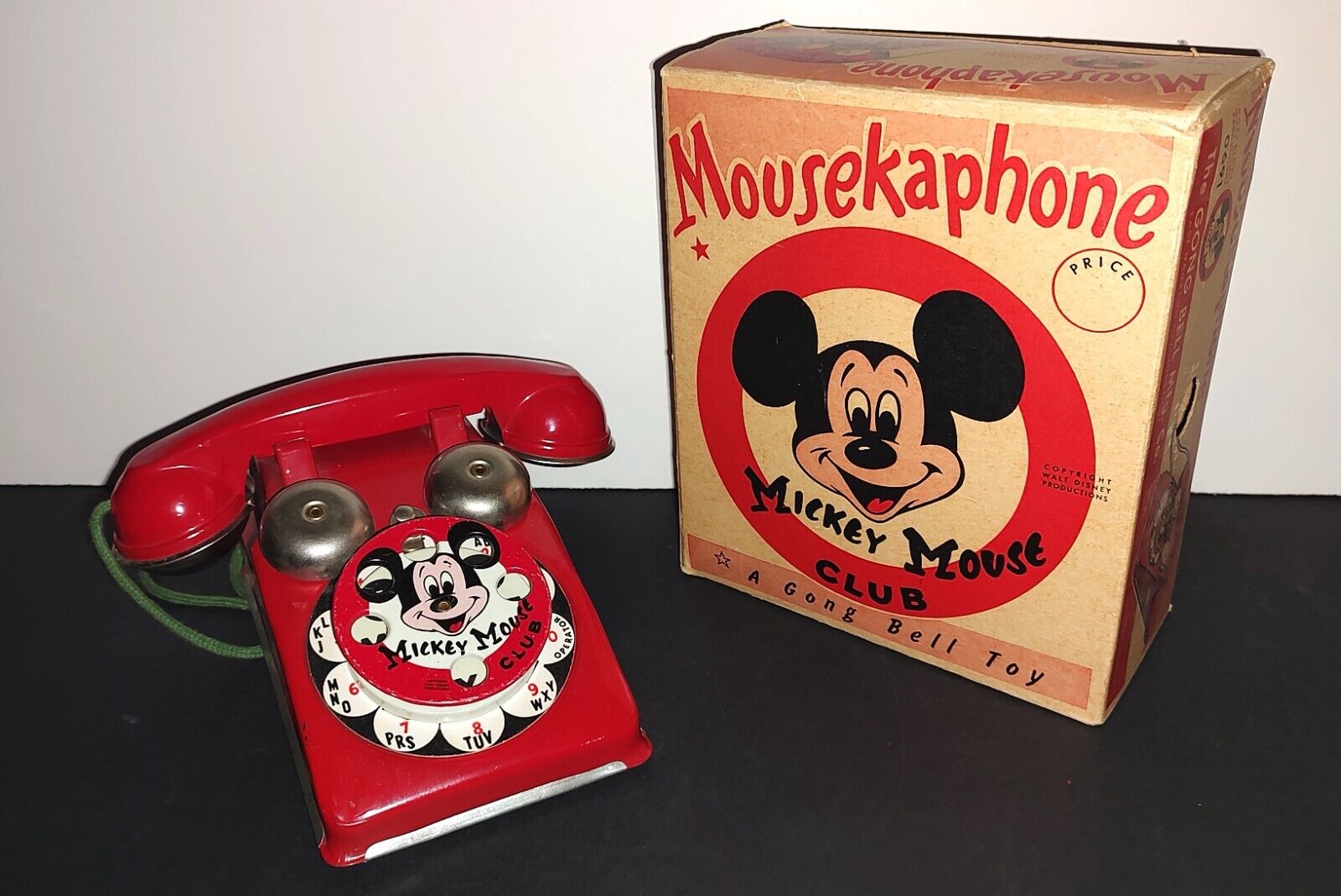

Beginning in 1955, ABC aired the massively popular variety show The Mickey Mouse Club. Mickey emerged from retirement as the show’s host. He showed up not only in vintage cartoons, but also in the show’s opening, interstitial, and closing segments.

If he was bland before, now Mickey became squeaky-clean — an avuncular stand-in for Walt himself. The main cast members of the The Mickey Mouse Club — including Bobby Burgess, Lonnie Burr, Tommy Cole, Annette Funicello, and Darlene Gillespie — constituted a wholesome cult: They wore Mickey/Minnie ears, and sang a paean of praise to the Mouse in each episode. They were known as the Mouseketeers.

In a 1999 essay in the journal Visual Resources, Barbara J. Coleman explains The Mickey Mouse Club like so: “During a time of economic abundance and Cold War vigilance, it taught group lessons about consumerism, appropriate social behavior, and good citizenship.”

During the Fifties, Mickey was simultaneously expanded and flattened out. As The Walt Disney Company’s mascot and logo, he was ubiquitous; but he no longer represented anything other than “wholesome family fun.” He no longer appeared as a character in movies; he was a corporate cheerleader.

Mickey was everywhere represented at Disneyland — which opened in Anaheim, California in 1955. Here, too, Mickey represented Walt himself. Mickey’s visage appeared everywhere — explicitly and subliminally. A costumed Mickey greeted visitors at the gate. Mickey was now Disney Co.’s official mascot — an avatar of The Walt Disney Company.

In a 2004 New York Times story, Jim Hardison — creative director of a company that revitalizes bygone cartoon characters — offered an explanation of why MM’s new status as the Disney Co. mascot would prove problematic for the character:

Disney says, “We are basically selling happiness.” But that requires a sort of ruthless efficiency that tends to undermine the whole fun-loving image they present. Over time, that shadow story has gained some traction with the audience, and as the symbol of what Disney stands for, Mickey can’t help but pick up a little bit of that shadow.

I’ve suggested elsewhere that statues of unelected leaders — let’s call them despots — are meaning-bearing sign vehicles whose purpose it is to elicit or provoke, at a preconscious level, a desire to see that statue toppled and beheaded. Mickey Mouse became exactly this sort of icon, beginning around 1954. As a result, the Mickey backlash went mainstream.

Precisely because Mickey had become a symbol of America’s inherent innocence, goodness, and can-do optimism, artists and activists with a more skeptical view of America would seize upon Mickey as a handy symbol, the subversion of which had a certain amount of guaranteed shock value.

The beginning of decolonization took place in the Fifties; a kind of psychic decolonization was also happening within America itself. Mickey — perceived as a cheerleader for capitalism and America’s global cultural hegemony — would now become the target of subcultural freedom fighters.

It’s important to point out that — for the most part, it seems to me — these satirical anti-Mickey expressions are coming from a place of frustrated love. Will Elder and Harvey Kurtzman, Ed “Big Daddy” Roth, Roy Lichtenstein, and others who parodied or poked fun at Mickey from 1954–1963 didn’t hate the character. They admired and missed what he once represented — wit, anarchic playfulness, elasticity — and lamented what he’d become.

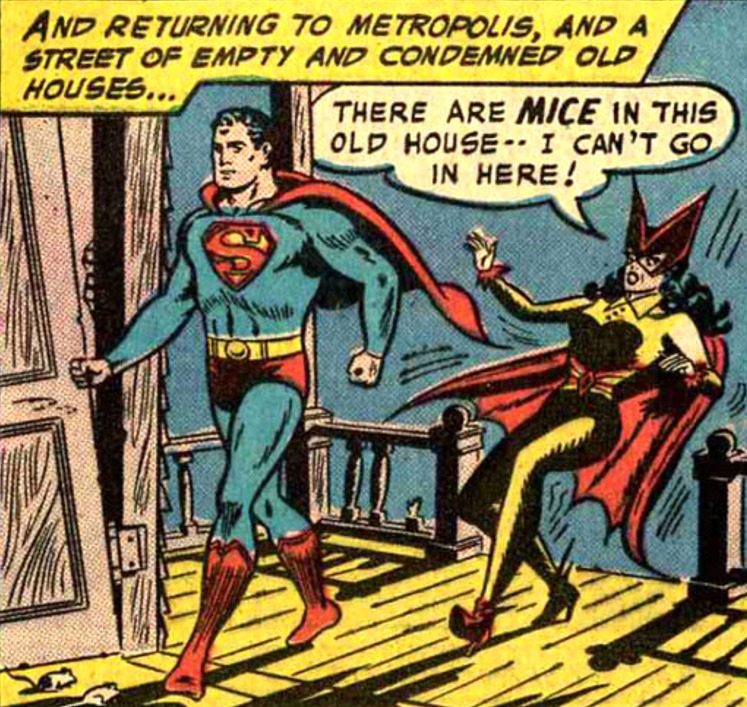

Note that the “Eek! A mouse!” trope seems to be used satirically by now…

Claws for Alarm is a 1954 Merrie Melodies cartoon directed by Chuck Jones. A group of mice terrorize Porky Pig and Sylvester.

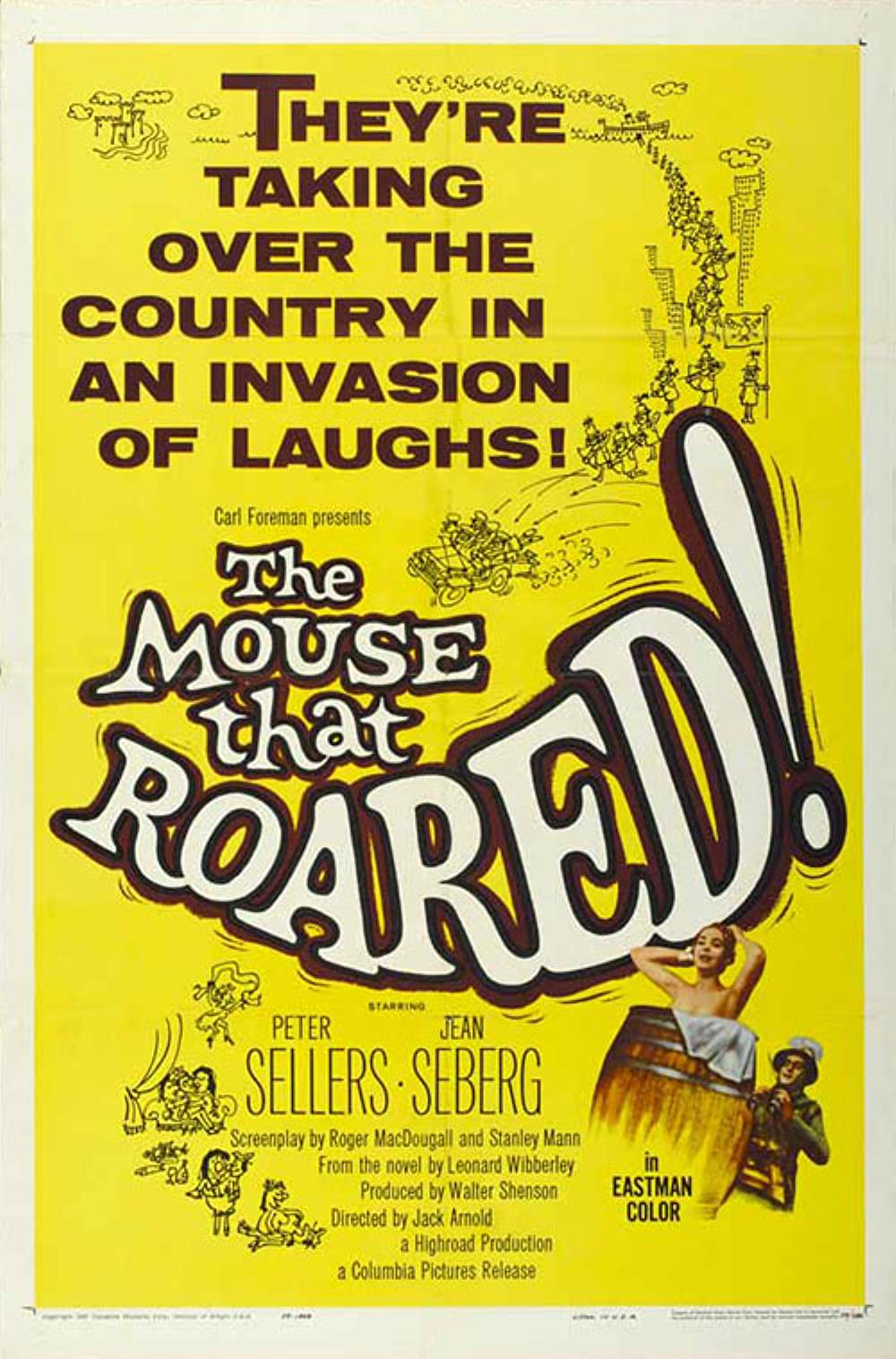

The 1959 live-action movie The Mouse That Roared opens with an animated sequence in which the Columbia Studios woman-with-torch logo suddenly hikes up her gown and flees from a mouse at her feet.

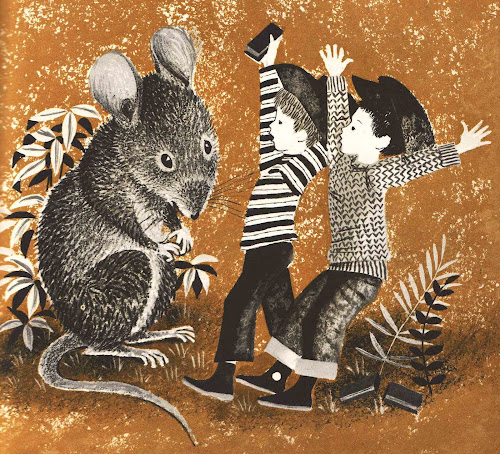

Here’s a twist on the ABJECT OTHER trope. The Mouse and the Lion (1962) by Eve Titus — illustrations by Leonard Weisgard — features a lion and mouse who decide they’d love to visit the land of people. A meddling fairy decides that the mouse would be too afraid of towering people and that people would run screaming from a ferocious lion. So…

Millie the Model shrieking in mock fear. Millie the Model Comics #109 (Marvel, July 1962). “The Command Performance,” written by Stan Lee.

During the wizards’ duel in The Sword in the Stone (1963), Mad Madam Mim turns herself into an elephant; but Merlin then turns himself into a mouse, which (briefly) scares her off. (Note that Merlin Mouse is technically an alliterative MM character.)

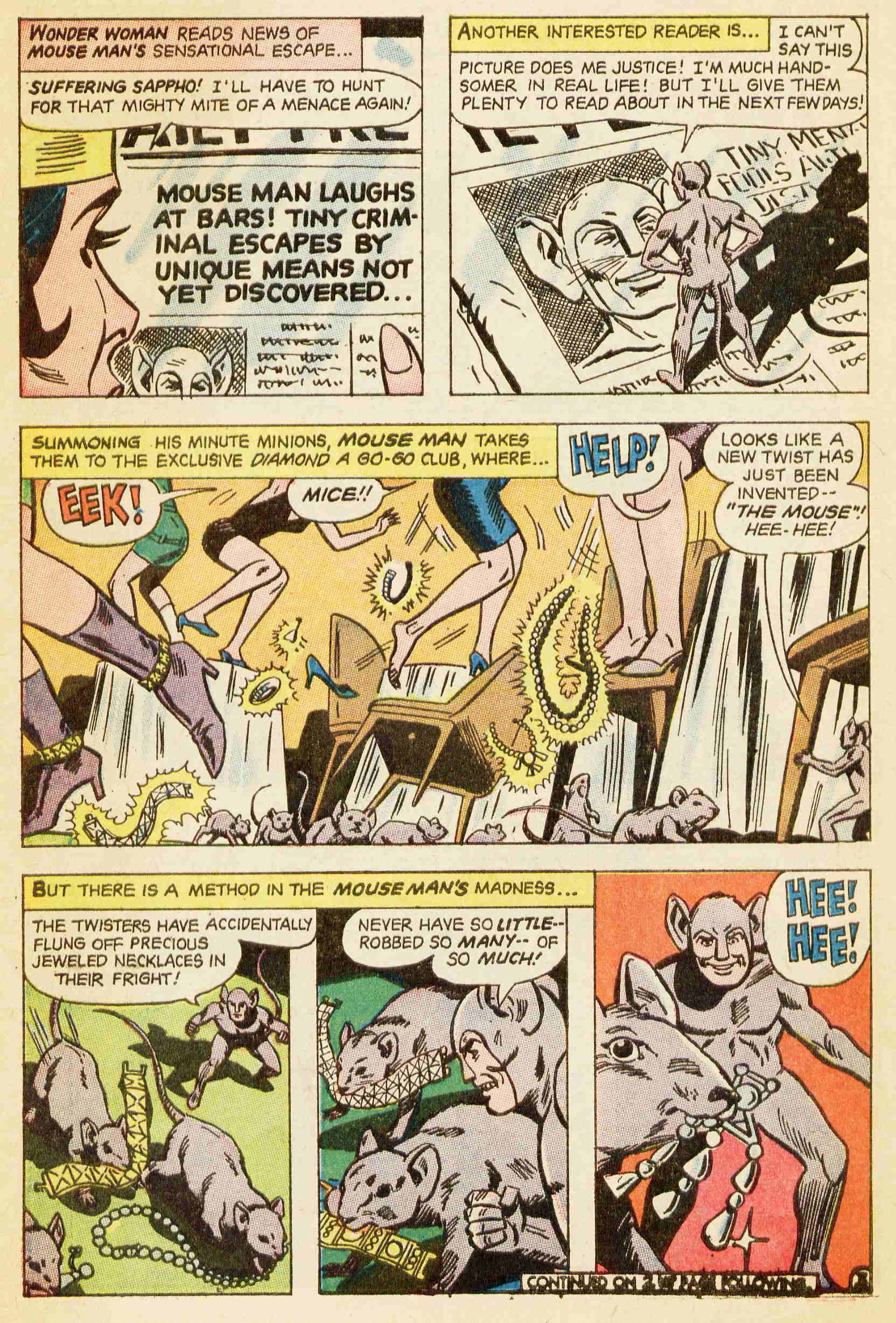

Mouse Man, who shrinks himself to the size of a mouse (and controls mice) made his debut as a member of the Academy of Arch-Villains, attacking Wonder Woman in Wonder Woman #141 (October 1963). Created by Robert Kanigher and Ross Andru. Note that Marvel’s Ant-Man’s first appearance was in Tales to Astonish #27 (January 1962).

Wonder Woman continued to visit Mouse Man in prison, attempting to reason with Mouse Man into reforming. At one point, he broke out of prison and used mice to scare women into dropping their jewelry. Yeesh.

An alliterative MM character.

In the flip side of “Professor Tom” (1948), Jerry has just earned his diploma in the art of outwitting cats. So he tries to teach Tuffy how to outwit Tom. In the end, Tuffy forms a friendship with Tom. This forces Jerry to throw away his diploma and learn from Tuffy how to appreciate cats.

Stray thought: As we saw in the previous installment in this series, during WWII, Nazi Germany was not infrequently depicted as a cat in US pop culture; and the mouse was an antifascist foe of the cat. After the war, Germany, and its capital, Berlin, were divided into four zones occupied by Allied powers. In 1955, the United States established diplomatic relations with West Germany. Coincidence that the mouse establishes friendship with the cat?

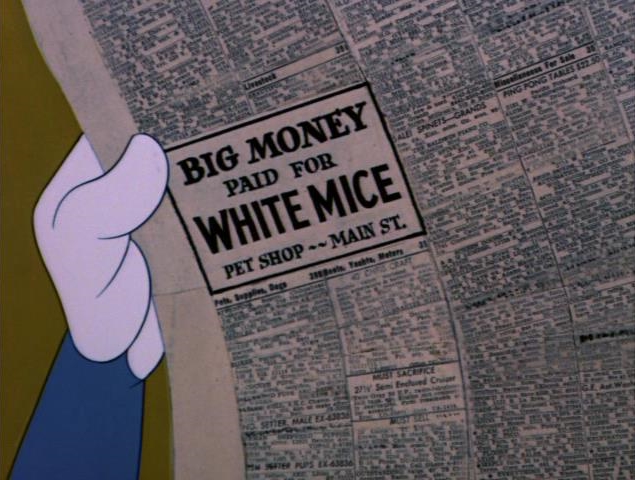

Tom sells Jerry to a local pet store that’s buying white mice. Yes, Jerry’s brown, but a little paint fixes that.

The Unexpected Pest is a 1956 Merrie Melodies short directed by Robert McKimson. Sylvester catches the same mouse over and over again to prove that he’s still of use to his owners. The mouse catches on to the fact that Sylvester needs him to stay alive, and he starts intentionally endangering himself to sabotage Sylvester’s efforts.

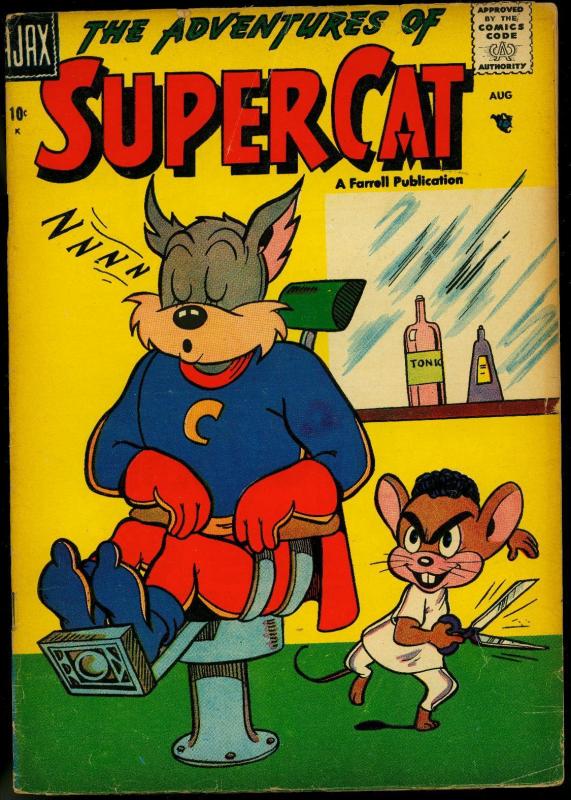

Stories and art by Al Fago, Milt Hammer, Charles W. Winter and Mickey Klar Marks. Adventures of funny animals with alliterative names, although curiously, no actual Super Cat stories. The covers of each of the four issues in this series show mice taunting and hassling Super Cat.

Not until issue #3 will the titular Super Cat show up; here he battles an invasion force of Martian mice.

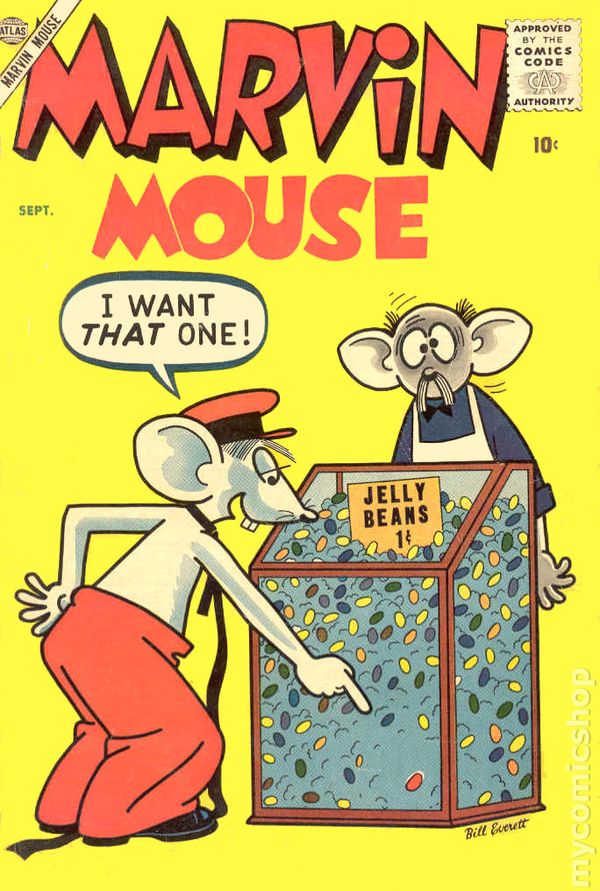

Stan Lee and Bill Everett teamed up to produce a funny animal comic book for Atlas. This was the only funny animal series with Bill Everett art.

An alliterative MM character.

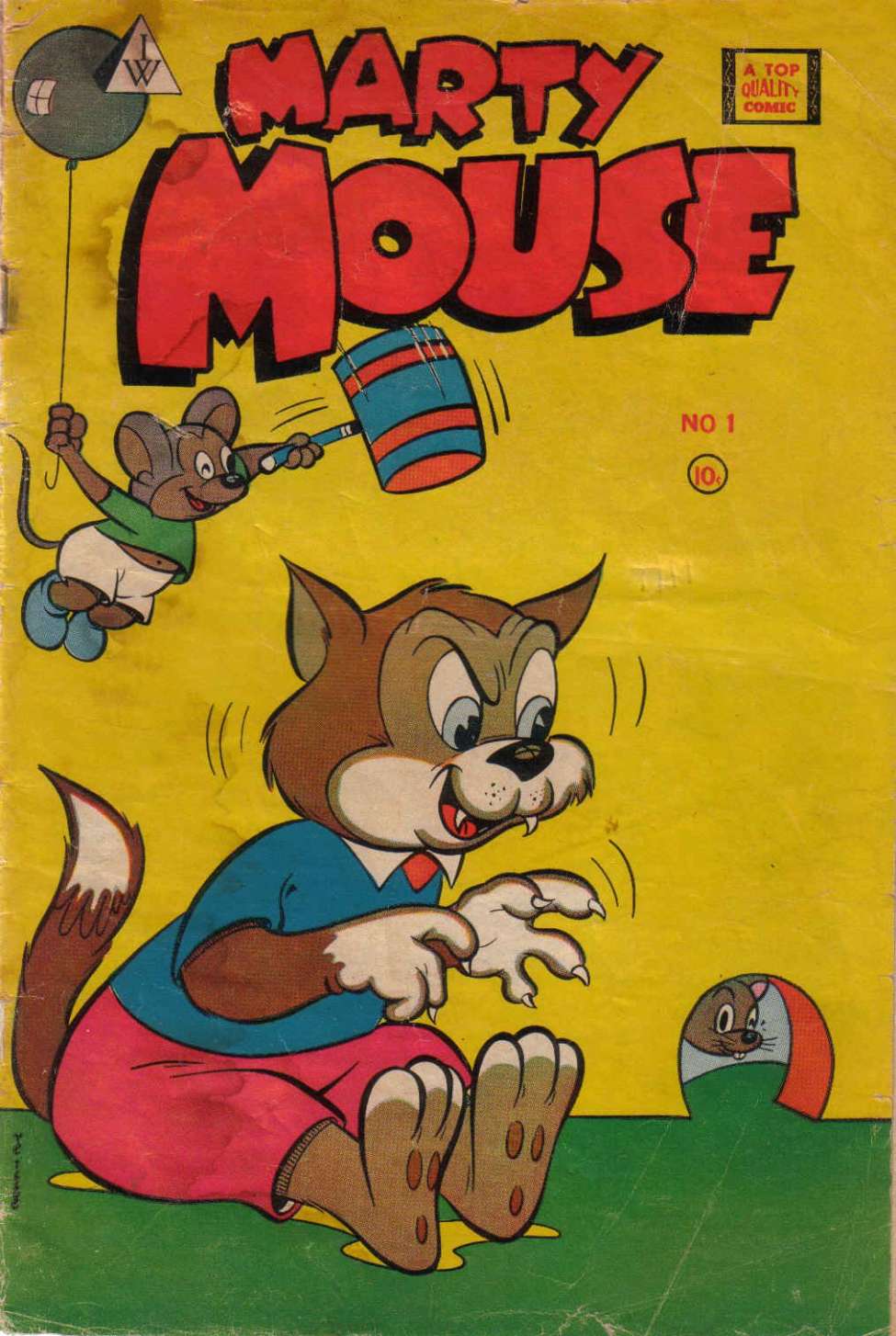

A good example of how the “residual” works in culture — sticking around forever…. A one-shot.

I.W. Publications (also known as Super Comics) was a short-lived comic book publisher in the late 1950s and early 1960s named for the company’s owner, Israel Waldman. The company was known for its low-budget products: most of I.W.’s comics were sold in grocery and discount stores, often in “three comics for a quarter” plastic bags. Waldman bought comics originally published by some of the dozens of comics publishers who’d gone out of business by then: Avon Comics, Fiction House, Magazine Enterprises, etc. Marty Mouse was the only original comic from this publisher.

An alliterative MM character.

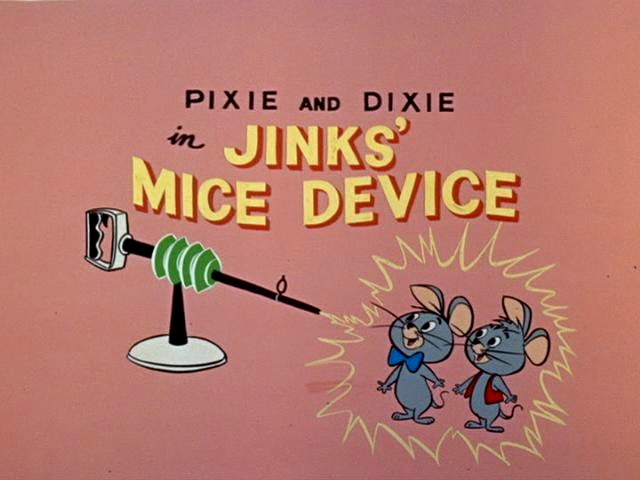

Pixie and Dixie and Mr. Jinks is an animated television series produced by Hanna-Barbera Productions as part of The Huckleberry Hound Show from 1958 to 1961. The series stars the bow-tied Pixie (voiced by Don Messick) and the vested Dixie (voiced by Daws Butler), and Mr. Jinks the cat (also voiced by Butler, impersonating Marlon Brando), a Beatnik who “hates those meeces to pieces! Jinks has, like, his own set of, like, verbal tics, y’know.

Pixie, Dixie, diddly-dum

Are the best of friends

Pixie, Dixie, diddly-dum

Are friends to the end

Pixie, Dixie, diddly-dum

Sometimes enjoy a spat

Pixie, Dixie, diddly-dum

With Mr. Jinks the cat!

PS: An interesting trait that makes Pixie and Dixie distinct from other cat/mouse cartoons — Pixie and Dixie are more often than not somewhat friendly to Jinks.

After the MGM cartoon studio closed in 1957, MGM revived the Tom and Jerry series with Gene Deitch directing an additional 13 shorts for Rembrandt Films from 1961 to 1962. Tom and Jerry then became the highest-grossing animated short film series of that time, overtaking Looney Tunes. However, unlike the Hanna-Barbera shorts, none of Deitch’s films were nominated for nor did they win an Academy Award.

Deitch came to see what he perceived as the “biblical roots” in Tom and Jerry’s conflict, similar to David and Goliath, stating “That’s where we feel a connection to these cartoons: the little guy can win (or at least survive) to fight another day.”

Since the Deitch/Snyder team had seen only a handful of the original Tom and Jerry shorts, and since the team produced their cartoons on a tighter budget, the resulting films were considered surrealist in nature, though this was not Deitch’s intention. The animation was limited and jerky in movement compared to the more fluid Hanna-Barbera shorts, and often utilized motion blur. Background art was done in a more simplistic, angular, Art Deco-esque style. The soundtracks featured sparse and echoic electronic music, futuristic sound effects, heavy reverb and dialogue that was mumbled rather than spoken.

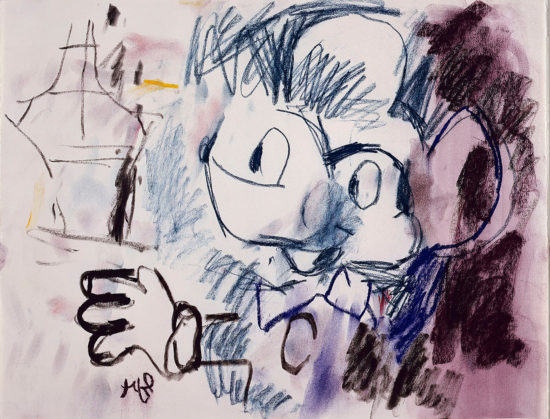

Roy Lichtenstein also grew up with Mickey; like Elder and Kurtzman, he no doubt felt disappointed and disgusted as he watched MM evolve into an insipid corporate mascot. Circa 1957, he began painting in the style of Abstract Expressionism — though he couldn’t help but subvert the genre’s austere strictures by incorporating hidden images of Mickey Mouse, Donald Duck, and Bugs Bunny into his paintings. (These canvases were destroyed when the artist used them as floor mats.) Above: A preliminary Lichtenstein drawing, “Mickey Mouse I” (1958).

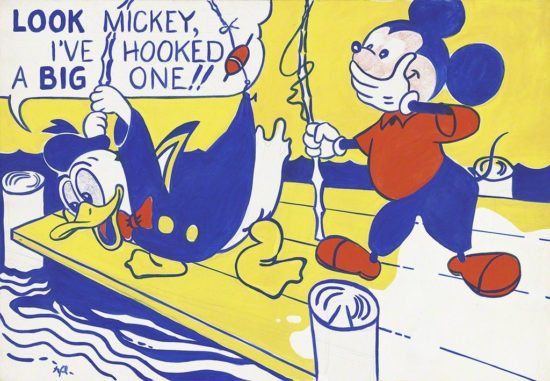

In 1960, Lichtenstein’s friend and Rutgers colleague, the avant-garde artist Allan Kaprow, who coined the phrase “happening,” introduced him to Andy Warhol and Claes Oldenburg. These artists’ interest in appropriating/recuperating pop culture imagery proved inspiring. In 1961, prompted by his children’s complaint that he couldn’t draw well, Lichtenstein painted his first full-scale Pop Art picture. He scaled up a scene of Mickey Mouse and Donald Duck out fishing (inspired by a scene from a 1960 children’s book, Donald Duck: Lost and Found); he included a speech bubble and laboriously stenciled Ben-Day dots, which were in those days used to produce inexpensive comic books and magazines.

Look Mickey is considered Lichtenstein’s most formative work. Bright, eye-popping and entertaining — but also deadpan, playfully subversive — the painting signaled Lichtenstein’s break from Abstract Expressionism’s emphasis on brushstroke, gesture, and the artist’s mark. Along with Warhol and Oldenburg, Lichtenstein found himself in the vanguard of the Pop Art movement. The painting somehow pokes fun at dumb, insipid MM while at the same time emulating the early MM’s pranksterism. Like the subject of Look Mickey, Lichtenstein would spend the rest of his career laughing up his sleeve at artists with delusions of grandeur.

Which is why I’ve included this version of MM in the REBELLIOUS SCAMP section.

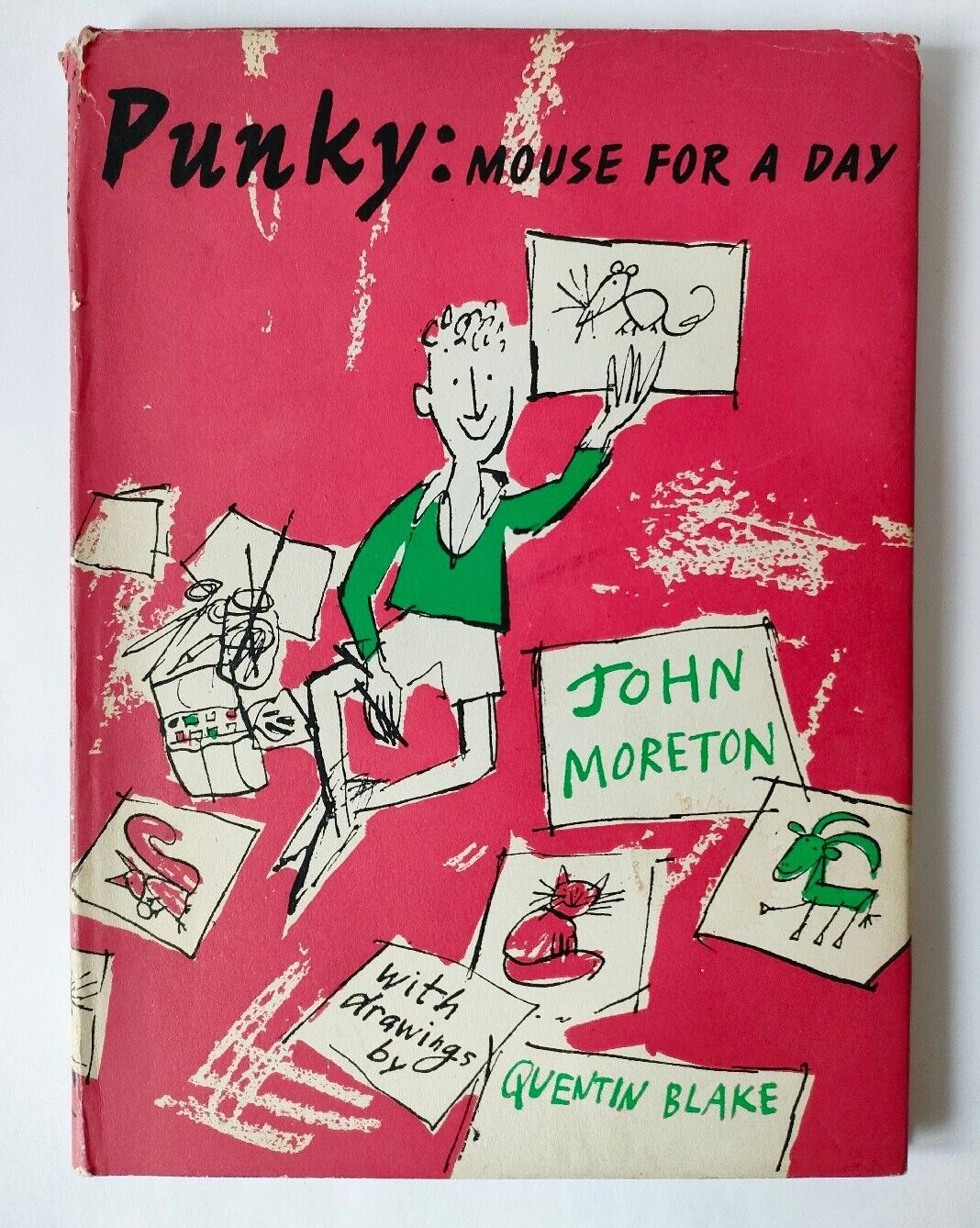

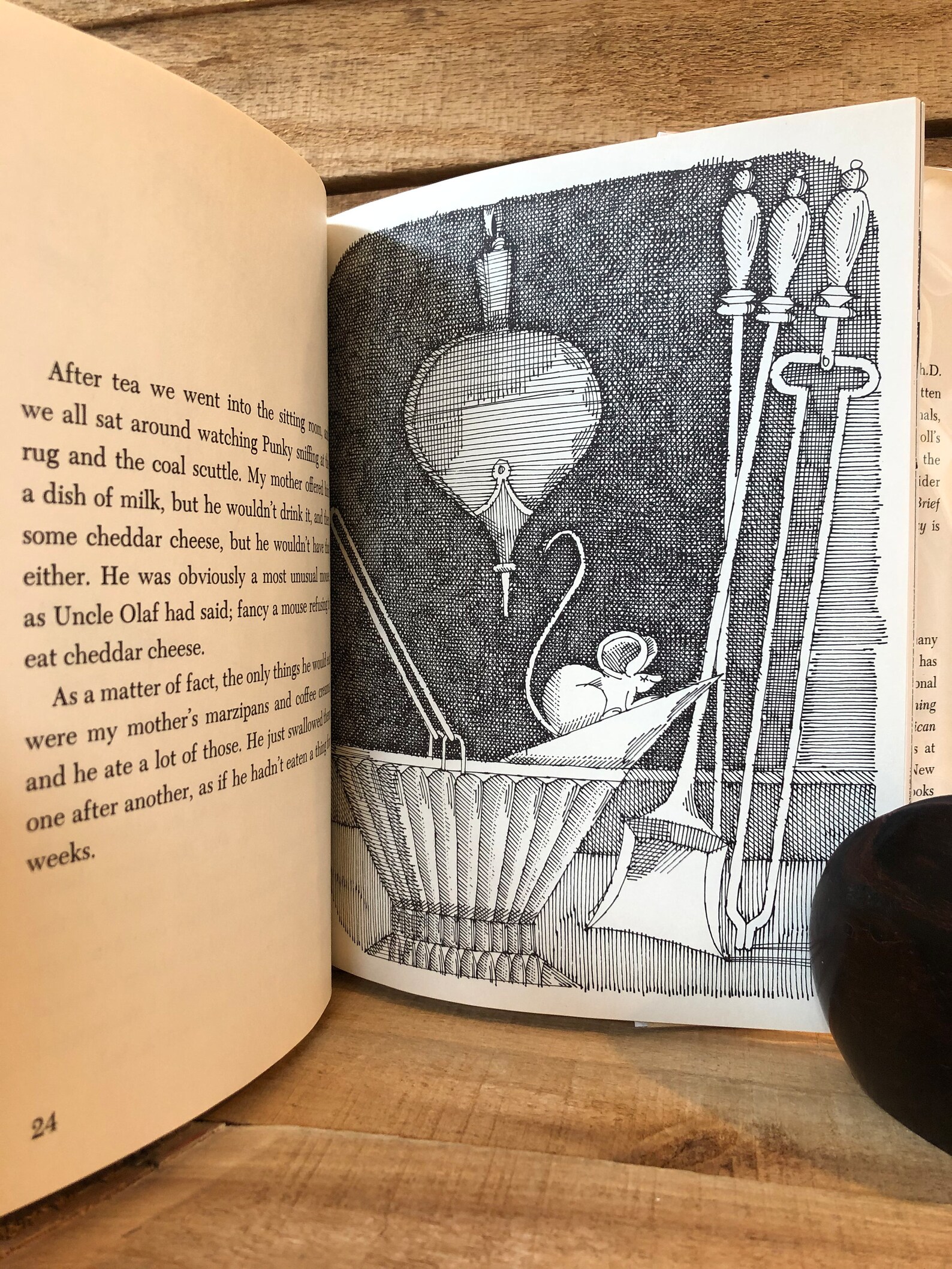

The original punk? The titular mouse from John Moreton’s Punky: Mouse for a Day (1962) is not content to remain in that form, and changes from one animal to another. Illustrated by Quentin Blake.

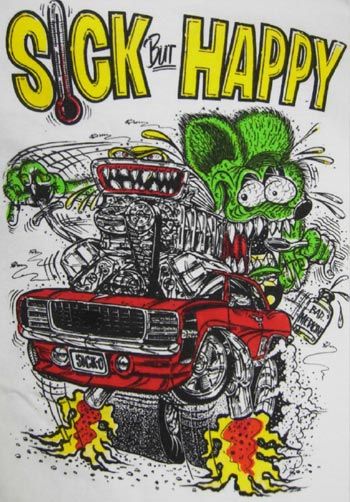

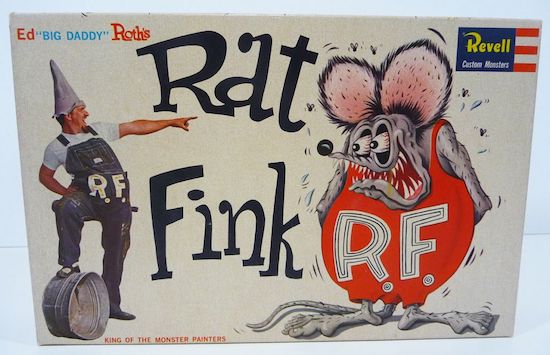

Here’s a brief consideration of Ed “Big Daddy” Roth’s hot-rod mascot Rat Fink. (Which breaks this series’ no-rats rule, but since we’re talking about an MM parody, we’re going to make an exception.)

Roth, an artist, cartoonist, and custom car designer and builder, became a key figure in Southern California’s Kustom Kulture and hot rod movement during the Fifties. Born a bit later than most of the other MM satirists discussed in this post, he likely was less familiar with the early — witty, anarchic, elastic — MM than they were. Instead, he would have grown up with the cheerful, gung-ho, pro-American, increasingy insipid Mickey… which perhaps explains why his parody is comparatively more savage. He lacks any love for MM.

A grotesque, slavering, mutated rodent with MM’s round ears, crazed eyes and sharp teeth, Rat Fink was originally intended to promote Roth’s custom car kits and art brand. However, after the anti-Mickey character first appeared in a Car Craft magazine ad in 1963, Rat Fink went viral. The Revell Model Company quickly issued a perennially popular plastic model kit of the character.

Big Daddy lived near Disneyland, and was thoroughly sick of seeing the Disney Company’s mascot on t-shirts, wallets, keychains, stickers, and toys. Throughout the Sixties (1964–1973), he’d get his revenge by selling innumerable Rat Fink shirts, wallets, keychains, stickers, and toys. RF remains a beloved emblem of weirdo culture.

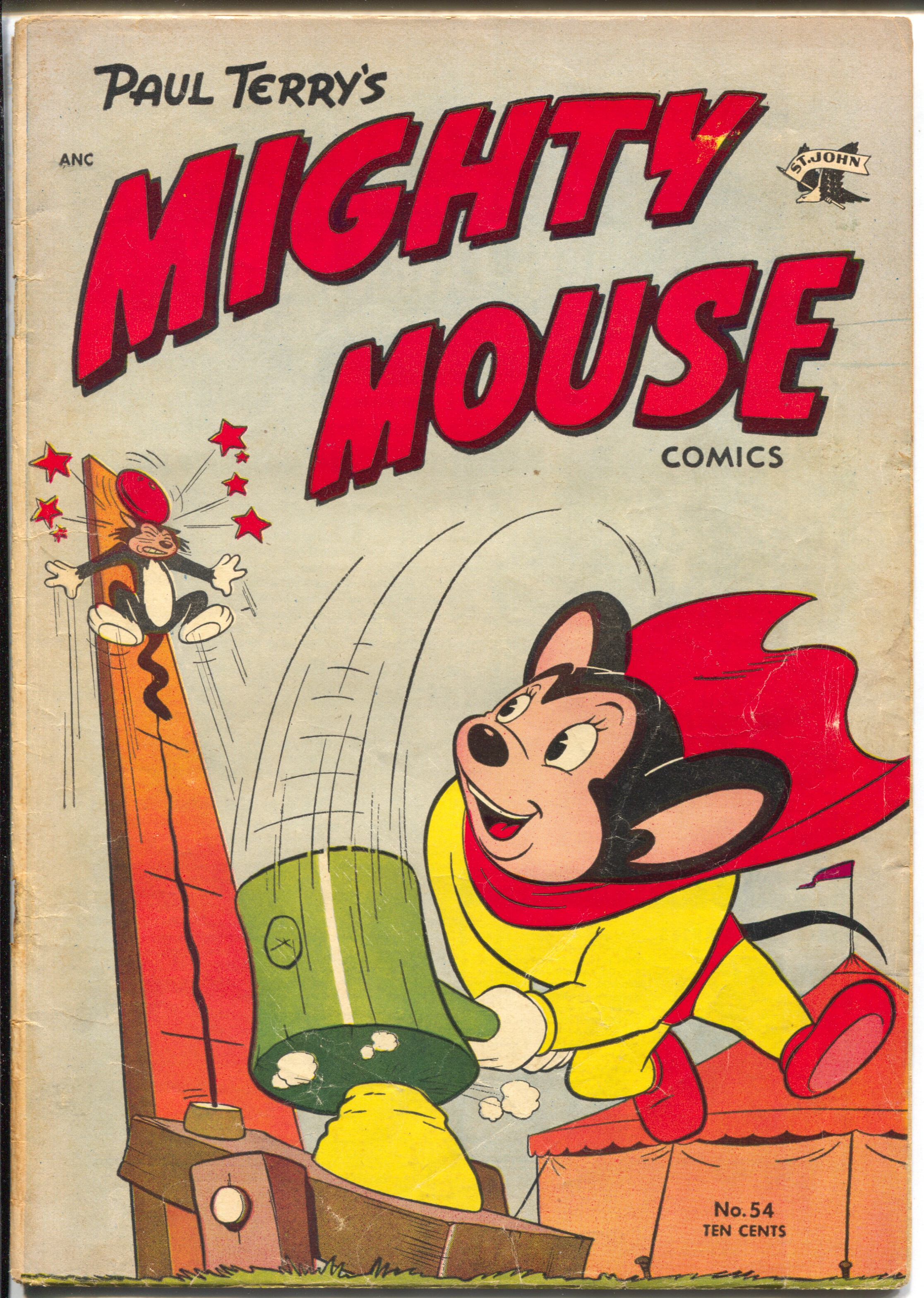

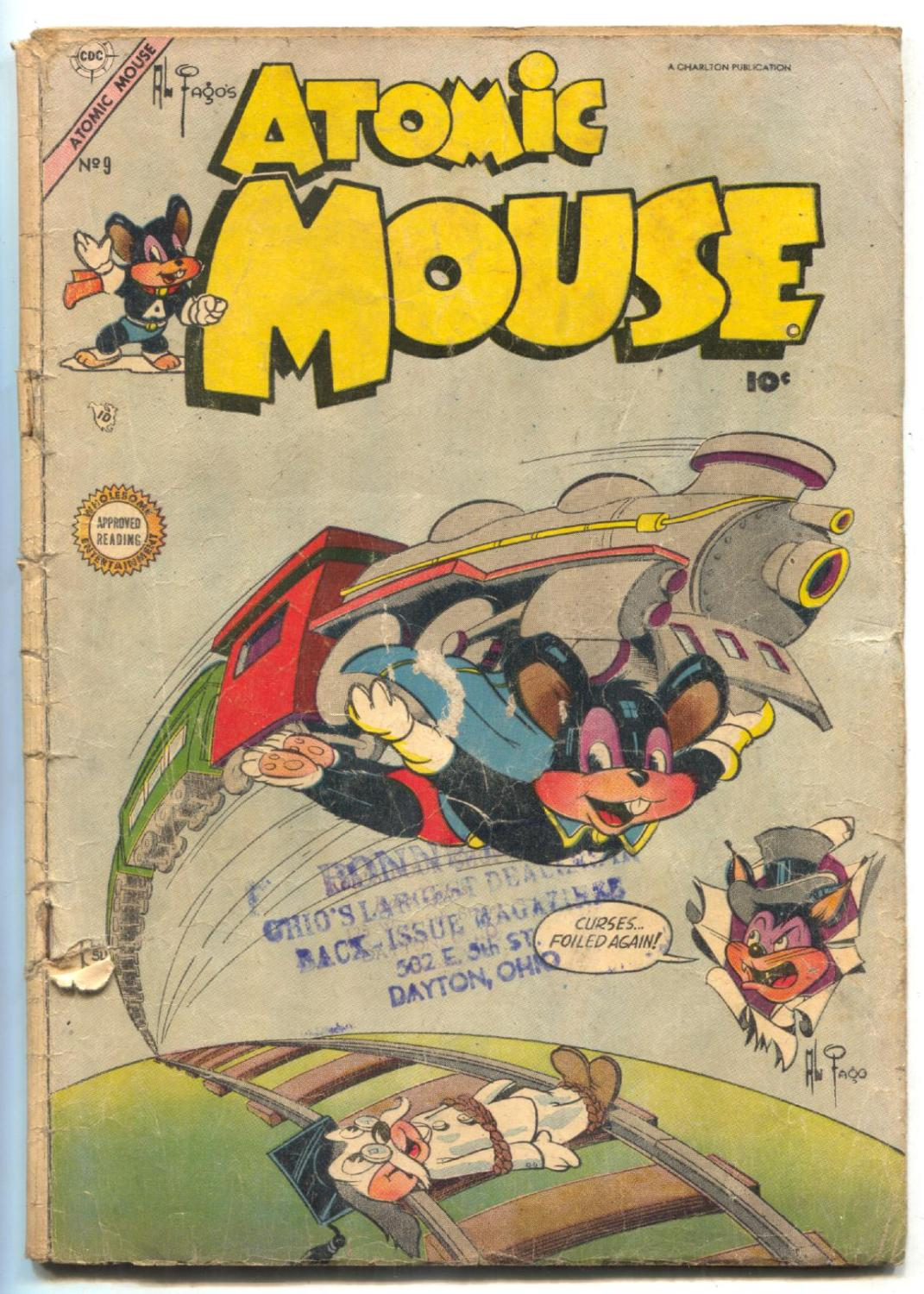

Mighty Mouse and Atomic Mouse still going (literally) strong in 1954.

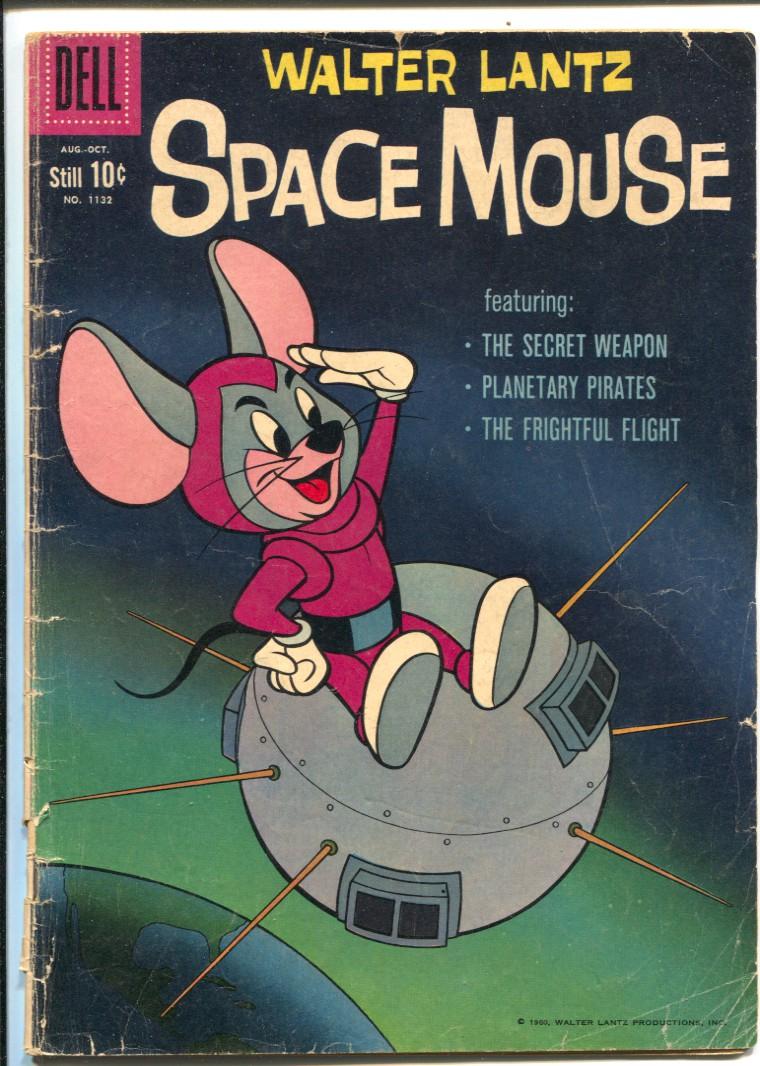

A second Space Mouse character (see previous installment) was published by Dell Comics (and later by Gold Key Comics) from 1960–1965.

The Dell Comics version was also featured in a 1960 cartoon produced by Walter Lantz, titled The Secret Weapon. Space Mouse lives on the planet Rodentia, but he prefers to spend his time flying around the galaxy in his Lunar Schooner. The planet is ruled by King Size, who lives in Camembert Castle, located in Miceapolis, the capital of Rodentia. One day, King Size learns that the cats on the planet Felinia are planning to invade Rodentia!

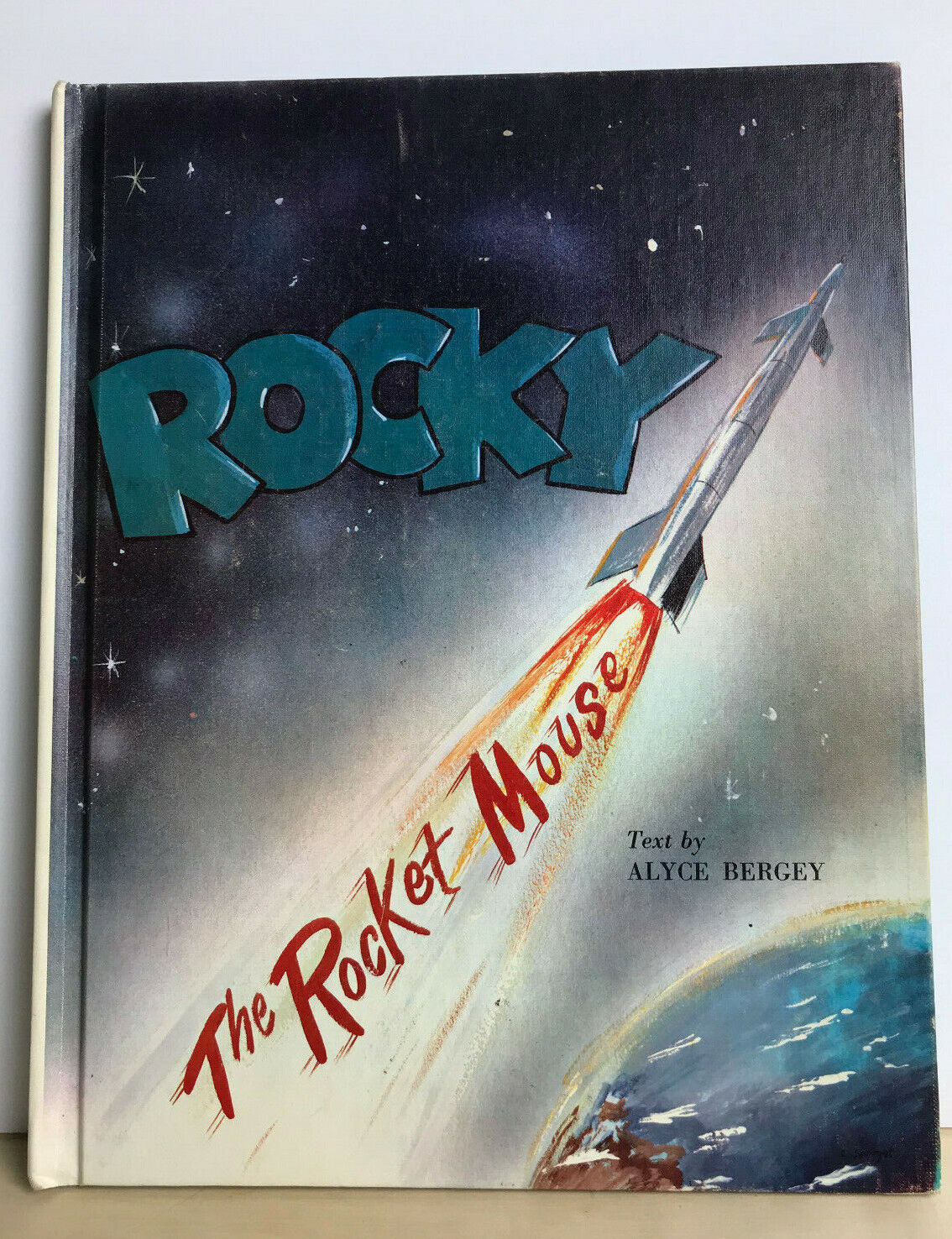

Another mouse in space!

And another!

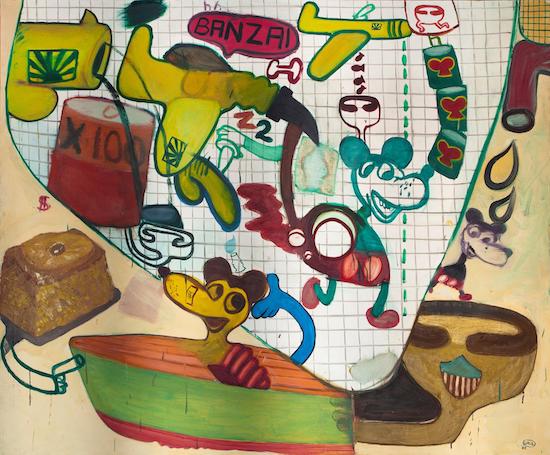

During the Fifties, Peter Saul developed his own unique, Pop Art-adjacent idiom. Influenced by MAD Magazine and Plastic Man, his genre-defying paintings satirized American culture and deliberately set out to offend good taste. During the Sixties, Saul would become well-known for his stream-of-consciousness, subjective interpretations of the Vietnam War, as well as ferocious psychological portraits of politicians and other personalities, in a tight linear style using Dayglo colors. I find it really instructive to look at his earlier work, which feels so contemporary…

Saul’s childish-looking 1962 painting Mickey Mouse vs. the Japs (the title of which suggests a parody of wartime Disney cartoons), above, appears — to this viewer — to poke fun not merely at Mickey Mouse, but at Pop Art’s appropriation of MM too. Saul demonstrates here a nobrow approach that’s a decade or two ahead of its time.

This MM, albeit in a parodic fashion, appears to be an INTREPID ADVENTURER.

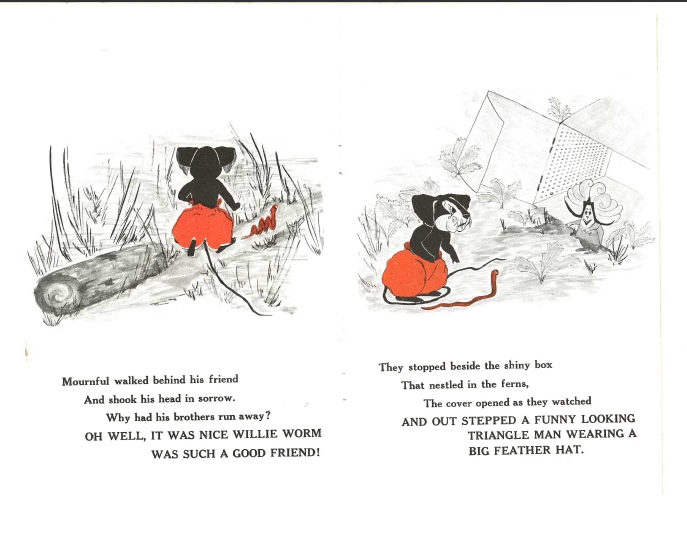

Mournful Mouse is an obscure MM who first appeared in the book Mournful Visits Grandma (1963). He seems an adventurous type; not sure why he’s so mournful. The image shown here is from a Mournful Mouse book in which he learns about angles.

An alliterative MM character.

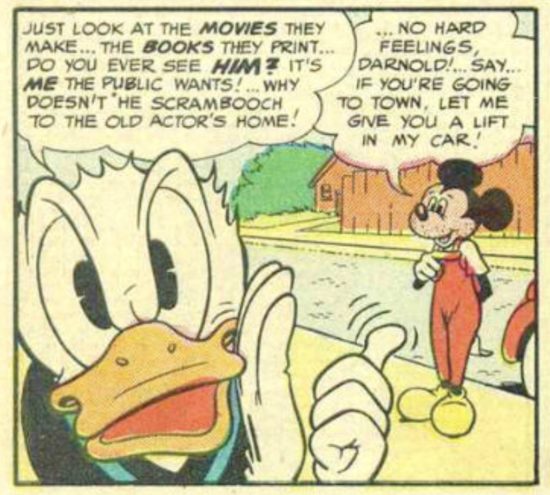

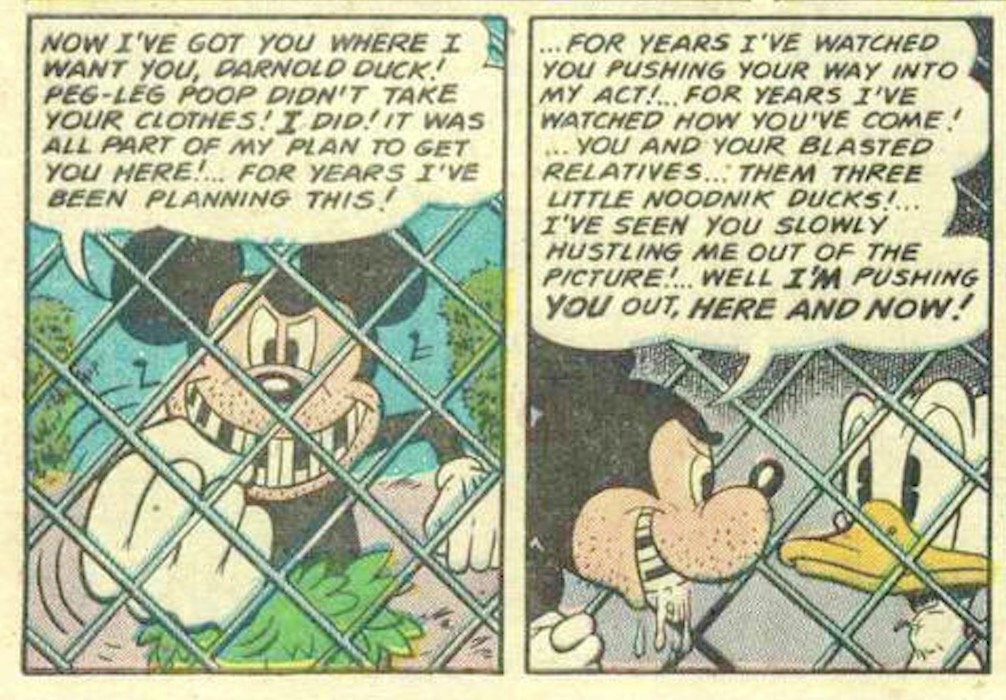

Will Elder and Harvey Kurtzman’s 1955 “Mickey Rodent!” strip, which appeared in Mad #19, portrays “Mickey Rodent” as an unshaven, washed-up movie star. Although he seems his usual chipper, friendly self — we discover that Mickey deeply resents “Darnold Duck” for having stolen his limelight.

MM here is a scrappy survivor in a showbiz sense — he’s desperate to reclaim the spotlight from his frenemy and rival.

As noted in the DONALD STEALS THE SHOW installment of this series, Elder and Kurtzman’s comic is funny… because it’s true. Beginning c. 1934, Donald Duck had eclipsed Mickey Mouse in popularity because — unlike Mickey, who’d become an increasingly bland role model for kids, and Disney’s corporate mascot — Donald remained irascible, lazy, pranksterish. So when Darnold Duck says, in an aside to the reader, “Just look at the movies they make… the books they print… do you ever see him? It’s me the public wants!”, he’s telling it like it is. We get the sense that Elder and Kurtzman aren’t just poking fun at Mickey Mouse; they’re also rooting for him to return to form, to stop being so lame.

In Mucho Mouse (1957), Tom, an award-winning mouse catcher, arrives in Spain to catch the flamenco dancing El Magnifico, (Jerry). Is this where Thomas Pynchon got the name of his character “Mucho” Maas?

An alliterative MM character.

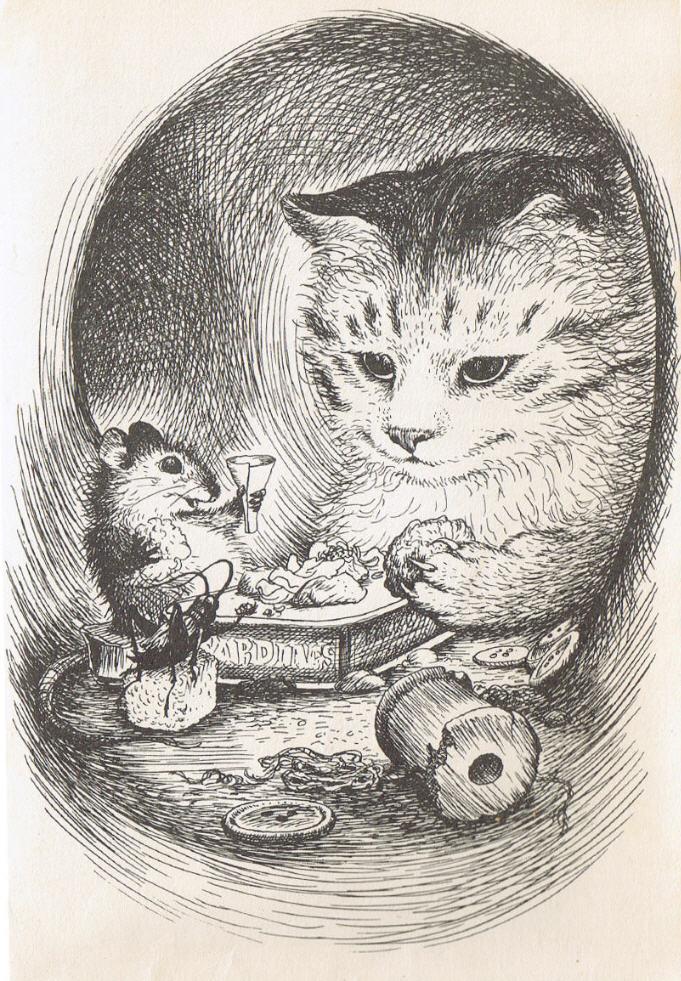

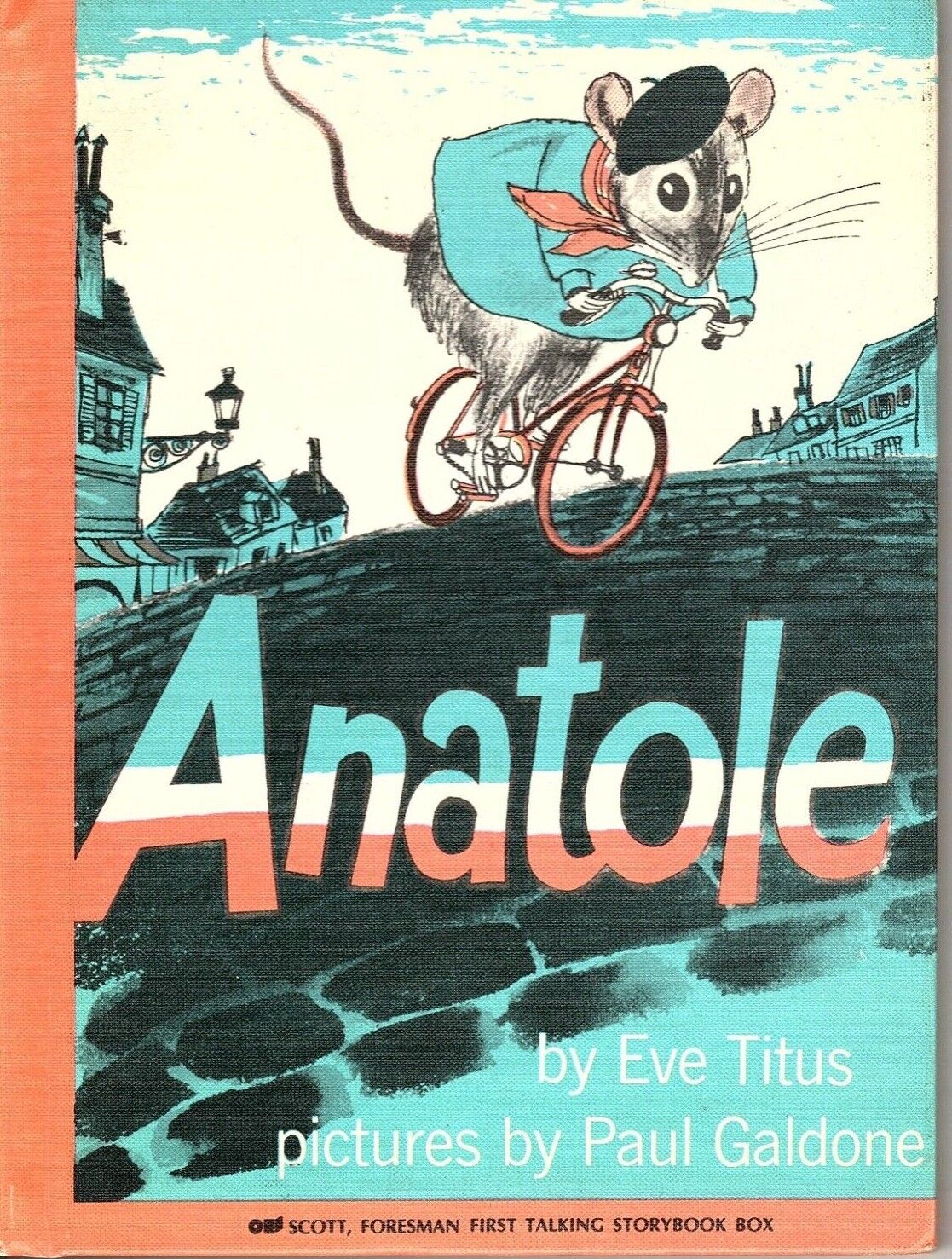

The sequel to 1956’s Anatole (see: RESOURCEFUL COLLABORATOR) tells the story of a mouse who secretly works at a cheese factory and what happens when the owner brings a cat to the factory.

Space Mouse is the title of a 1959 Universal Studios cartoon featuring two mice and a cat named Hickory, Dickory, and Doc. (Not the same as the Space Mouse comic published from 1953–1956 by Avon; see previous installment). Doc attempts to capture and sell Hickory and Dickory to NASA for laboratory tests.

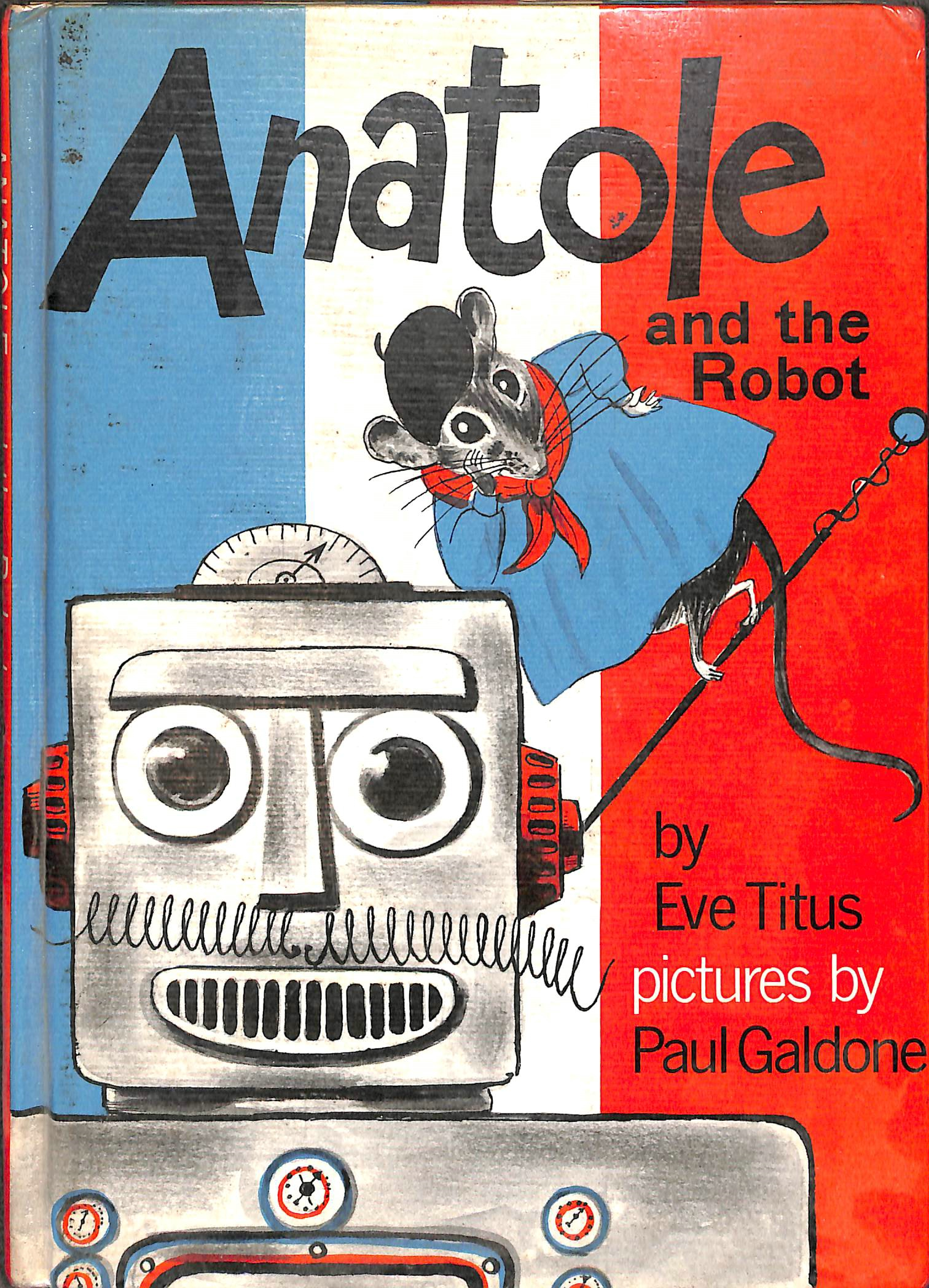

In Anatole and the Robot (1960), Anatole’s job as a cheese taster at the cheese factory is threatened by a cheese-tasting robot. Anatole works hard to prove his superiority over the machine and in the end saves his position at the factory.

The Mouse That Jack Built is a 1959 Warner Bros. Merrie Melodie cartoon short starring Jack Benny and the regular cast of The Jack Benny Program as mice. After inspecting his cheese vault, the mouse version of Benny takes mouse Mary (Mary Livingstone) to a nightclub… which turns out to be the inside of a cat. Jack cries: “Help! Help!” as the camera cuts to the live-action Jack Benny, who wakes up and, breaking the fourth wall, tells the audience: “Gee, what a crazy dream! Imagine, Mary and me as two little mice trapped inside a cat! And I was playing the violin!” At that point, Jack is interrupted by the sound of a discordant “Rock-a-Bye Baby” played on the violin, coming from within Jack’s live-action cat. From there, the rodent versions of Jack and Mary emerge unharmed from the live-action cat.

The Cricket in Times Square is a 1960 children’s book by George Selden and illustrated by Garth Williams. It won the Newbery Honor in 1961.

Mario Bellini finds Chester, a cricket, chirping near his parents’ newsstand in the Times Square subway station… it was transported there from Connecticut in a picnic basket. Papa Bellini allows Mario to keep the cricket in the newsstand as a pet. That evening, Chester meets Tucker Mouse and Harry Cat, best friends who live in an abandoned drainpipe near the newsstand. Tucker and Harry show him how to survive in the big city… and help him become something of a rock star.

In 1973, Chuck Jones wrote and directed a short animated version of The Cricket in Times Square with Mel Blanc cast as the voice of Tucker Mouse. Selden wrote six sequels to the book, including Tucker’s Countryside (1969) and Harry Cat’s Pet Puppy (1974).

The cartoon takes place in Naples, Italy, where Tom and Jerry arrive via cruise ship. Tom and Jerry’s chase leads an Italian mouse named Topo to defend Jerry from Tom’s attacks. Topo explains to Jerry (in Italian) that he dislikes it when a bigger creature picks on a smaller creature, which he proves when he saves Tom from being attacked by an Italian dog.

When Topo recognizes Tom and Jerry and realizes who they are, Topo explains that he’s a huge fan of their cartoons and befriends them. Topo shows the duo the sights and treats them to local delicacies.

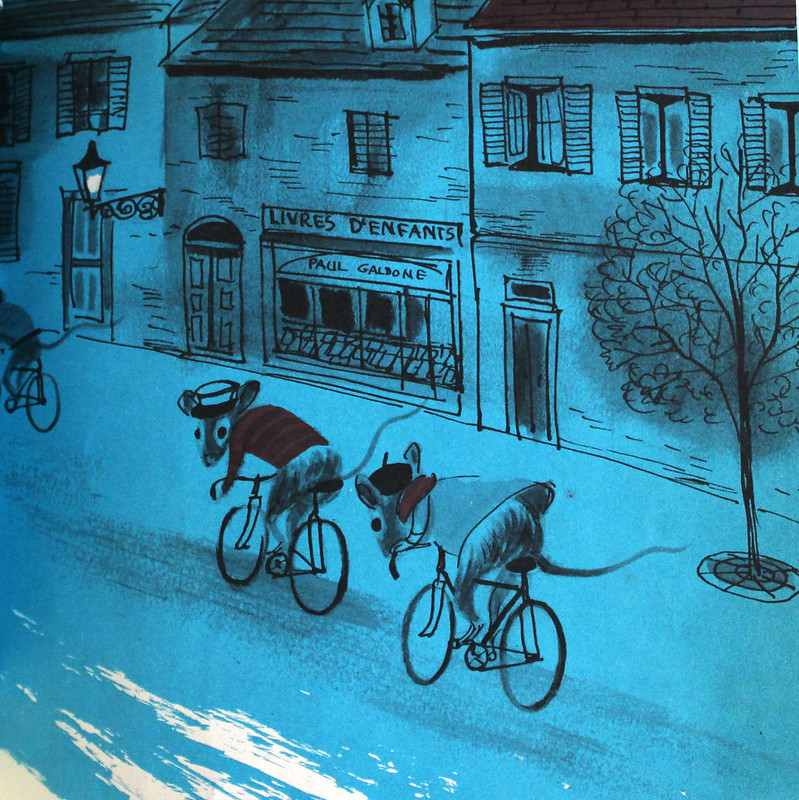

Anatole the mouse lives in a mouse village outside the city of Paris. One day, while commuting by bicycle to forage for food, he overhears some humans complaining about mice as villains. Aggrieved at the insult to his honor, Anatole goes to work in a French cheese factory as a taster and evaluator of the cheese. Working alone and anonymously late at night, he leaves notes to guide the cheesemakers in their work. His taste for good cheese leads to the factory’s commercial success. The factory’s human owners and workers hold his work in high esteem, although they have no idea that Anatole is a mouse.

This series first appeared, I think, c. 1956.

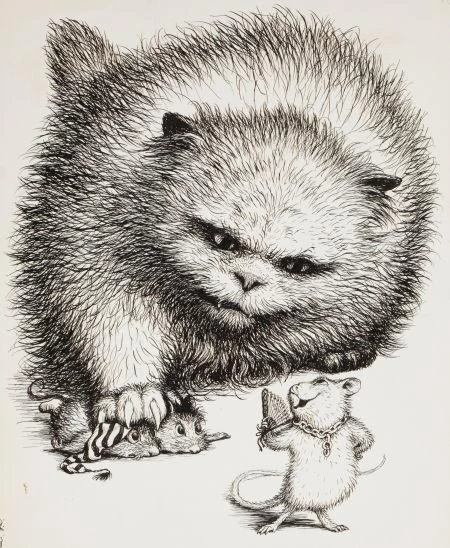

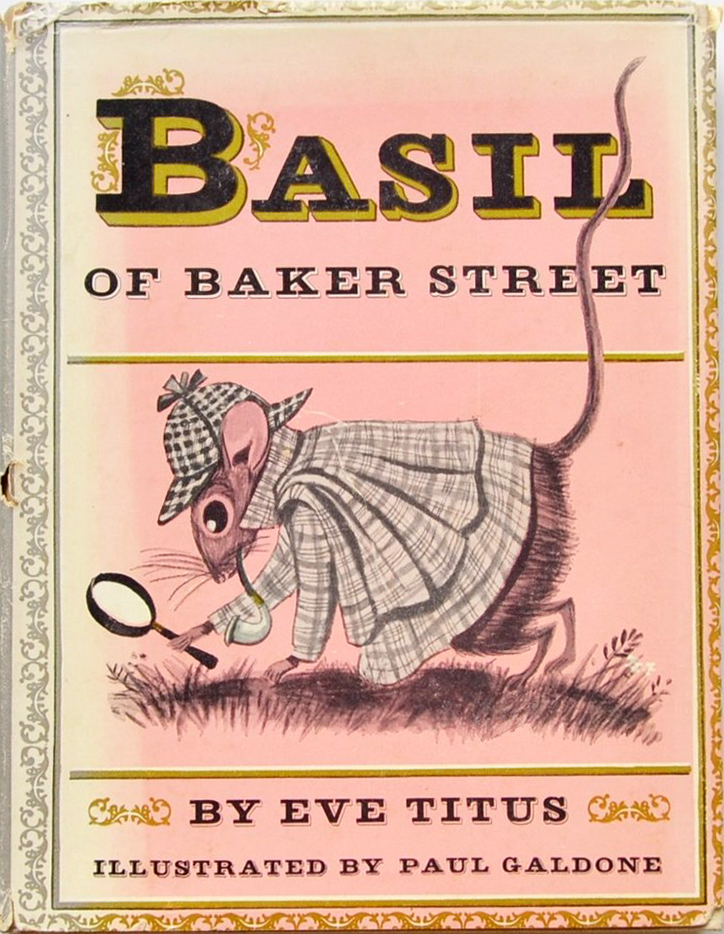

Basil of Baker Street is a series of children’s novels written by Eve Titus and illustrated by Paul Galdone (of Anatole fame). The stories — the first of which appeared in 1958 — focus on the titular Basil of Baker Street and his personal biographer Doctor David Q. Dawson. Together they solve the many crimes and cases of the mouse world. Both live in Holmestead, a mouse community built in the cellar of 221B Baker Street, where Sherlock Holmes is a tenant upstairs.

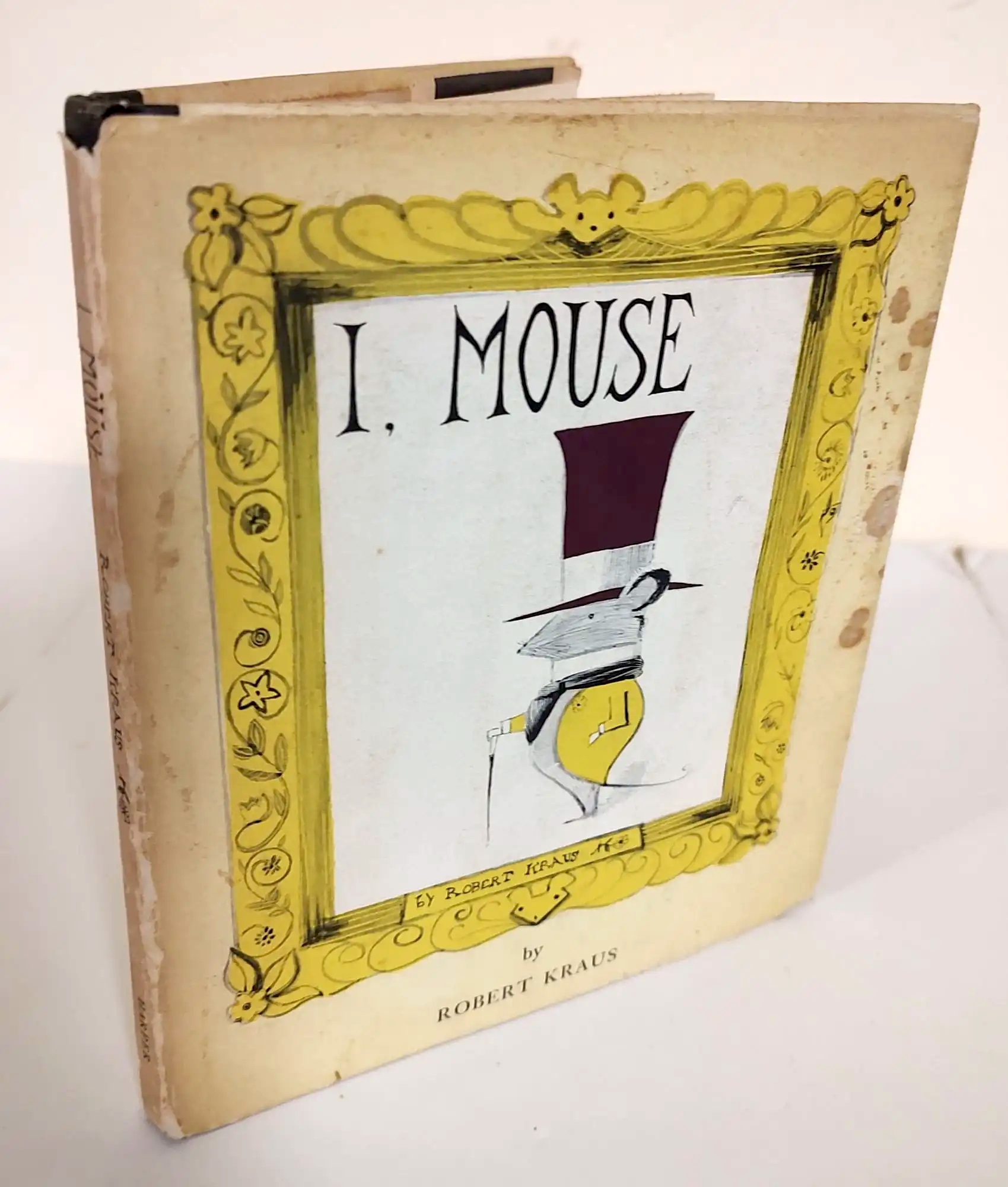

In Robert Kraus’s I, Mouse (1958), a lonely mouse lives with a family of humans. More than anything, he wants to be accepted for what he is, but the humans have other ideas (mostly involving cats and traps). When a burglar breaks in one night, the mouse has a chance to prove himself.

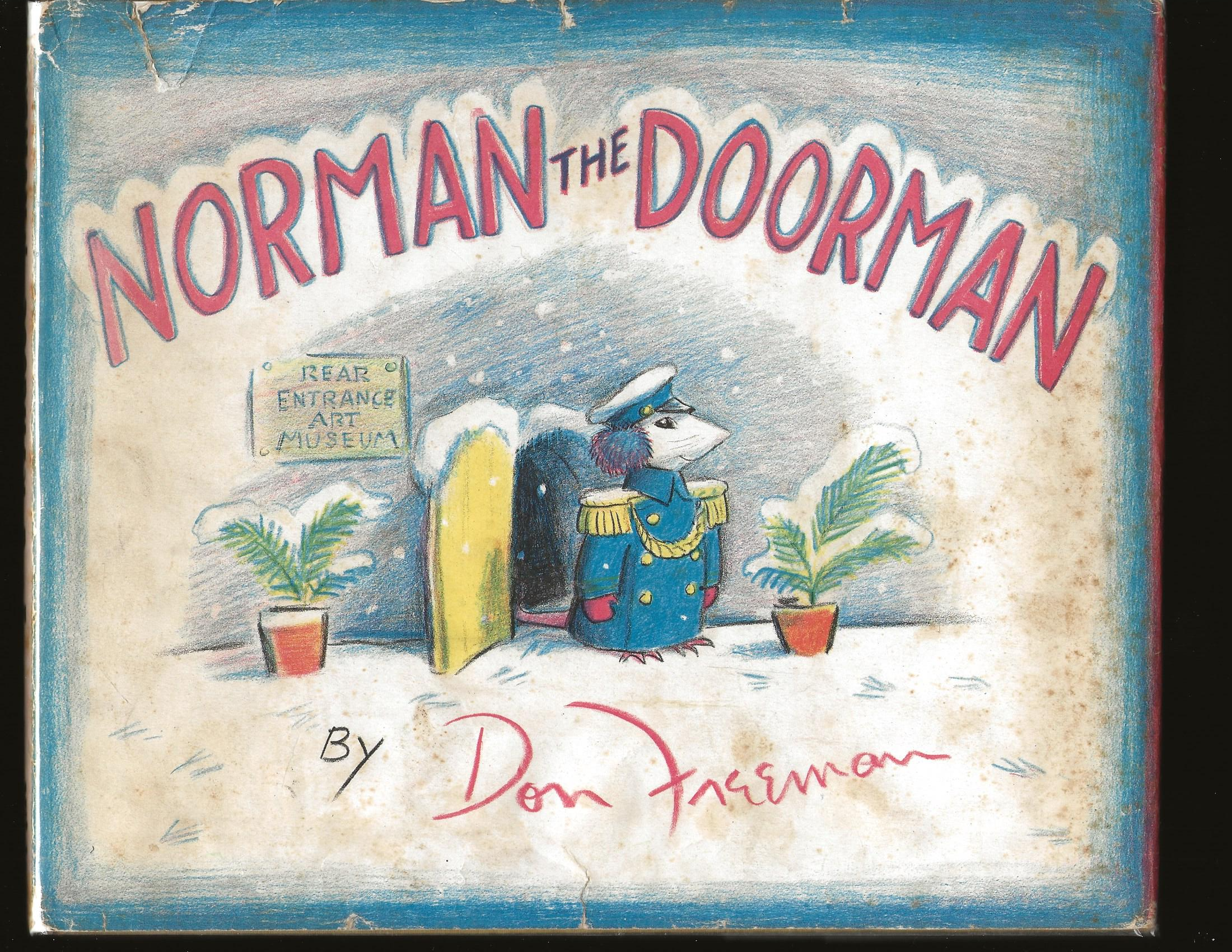

In 1959’s Norman the Doorman, Don Freeman gives us a mouse who is doorman of a mouse hole in an art museum. He uses his own art talent and finds a way to see the art treasures in the galleries upstairs.

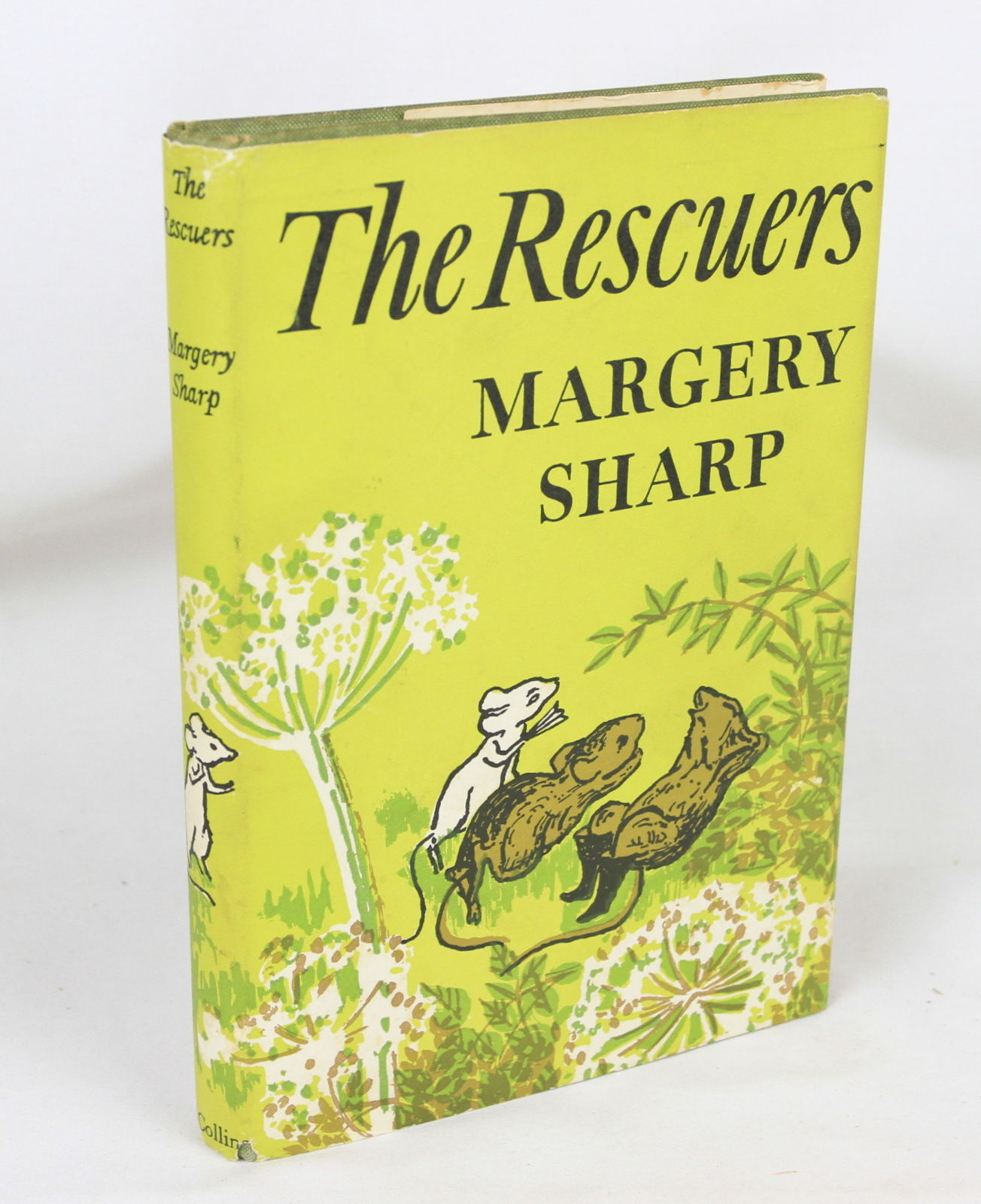

The ultimate example of this trope? The Rescuers is a British children’s novel written by Margery Sharp and illustrated by Garth Williams; its first edition was published in 1959. The first in a series of stories about Miss Bianca, a socialite mouse who volunteers to lend assistance to people and animals in danger.

The Mouse That Roared is a 1959 British satirical comedy film on a Ban The Bomb theme, based on Leonard Wibberley’s novel The Mouse That Roared (1955). It stars Peter Sellers in three roles: Duchess Gloriana XII; Count Rupert Mountjoy, the Prime Minister; and Tully Bascomb, the military leader; and co-stars Jean Seberg.

The title — which references the Lion and the Mouse fable — is a metaphor for a tiny, innocuous nation that ends up holding the fate of the world in its hands.

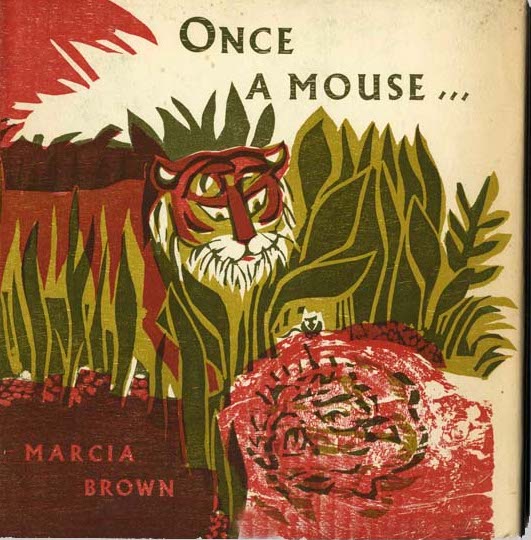

Once a Mouse is a 1961 children’s picture book by Marcia Brown. Released by Scribner Press, it was the recipient of the Caldecott Medal for illustration in 1962. I haven’t read it, but imagine it’s a RESOURCEFUL COLLABORATOR tale.

Best Word Book Ever by Richard Scarry was published in 1963 and became a best-selling children’s book. Scarry had been illustrating children’s books since 1950, but this was his first as both author and illustrator. Here he first depicted Busytown, inhabited by an assortment of anthropomorphic animals, including Huckle Cat, Lowly Worm, Bananas Gorilla… and a baker mouse named Able Baker Charlie.

PERHAPS ALSO WORTH MENTIONING IN THIS CONTEXT…

Chevy has a series of small-block V-8 engines that started in production in 1954. This 327-cubic-inch engine and 265-cubic-inch powerplant developed the nickname (among racers and rodders) “Mighty Mouse” because of its exceptionally compact and efficient engine design. The engine appeared first in the now-iconic 1955 Chevrolet.

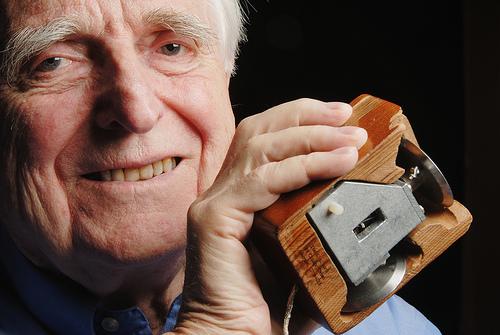

The computer mouse was invented by Douglas Engelbart in 1963 and consisted of a wooden shell, circuit board, and metal wheels. Its power cord reminded its inventor of a mouse’s tail.

Mouse Trap is a board game first published by Ideal in 1963. It is one of the first mass-produced three-dimensional board games.

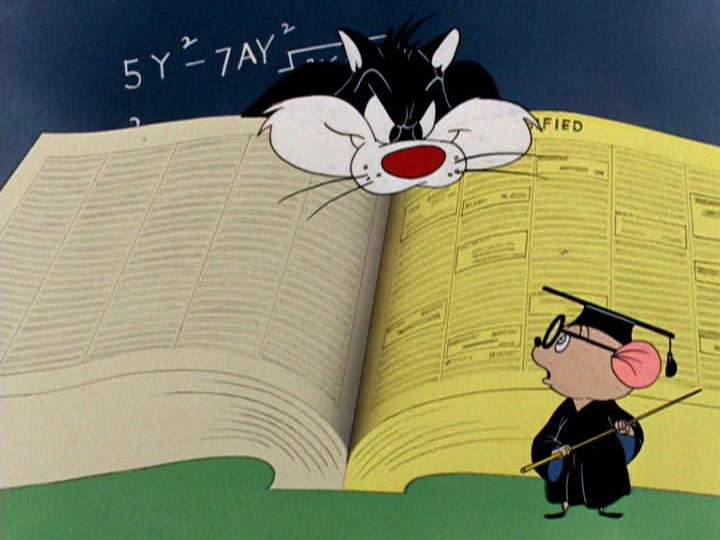

Hans, a German mouse, arrives in America to visit his cousin, Willie. Hans wants to know all about the free market capitalist system. So, Willie takes Hans to see a lecturer in a university, another mouse, who talks at length about the capitalist system while Sylvester Cat chases all three rodents around the lecture halls.

NB: This was the first of three cartoons on economic subjects underwritten by the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation. It was followed by Heir-Conditioned (1955) and Yankee Dood It (1956).

I’m including this propaganda in the HABITAT EXPERIMENTER section, because once again we find a mouse arriving from outside a social system and judging whether it’s better than the one he’s left.

“Once upon a time there was a little mouse house. It was like a doll’s house, but not for dolls, for mice.” Not proper mice, but a flannel He-Mouse and She-Mouse with beady eyes and bristle whiskers who stand quite still, propped on their hind legs in the sitting room. Mary knows real mice run and scamper, and disappointed with her new gift, she puts the mouse house away in her room. Meanwhile, down in the basement, a real mouse named Bonnie has been jostled out of her woefully inadequate flowerpot home by her older brothers and sisters….

INTRODUCTION by Matthew Battles: Animals come to us “as messengers and promises.” Of what? | Matthew Battles on RHINO: Today’s map of the rhinoceros is broken. | Josh Glenn on OWL: Why are we overawed by the owl? | Stephanie Burt on SEA ANEMONE: Unable to settle down more than once. | James Hannaham on CINDER WORM: They’re prey; that puts them on our side. | Matthew Battles on PENGUIN: They come from over the horizon. | Mandy Keifetz on FLEA: Nobler than highest of angels. | Adrienne Crew on GOAT: Is it any wonder that they’re G.O.A.T. ? | Lucy Sante on CAPYBARA: Let us gather under their banner. | Annie Nocenti on CROW: Mostly, they give me the side-eye. | Alix Lambert on ANIMAL: Spirit animal of a generation. | Jessamyn West on HYRAX: The original shoegaze mammal. | Josh Glenn on BEAVER: Busy as a beaver ~ Eager beaver ~ Beaver patrol. | Adam McGovern on FIREFLY: I would know it was my birthday / when…. | Heather Kapplow on SHREW: You cannot tame us. | Chris Spurgeon on ALBATROSS: No such thing as a lesser one. | Charlie Mitchell on JACKALOPE: This is no coney. | Vanessa Berry on PLATYPUS: Leathery bills leading the plunge. | Tom Nealon on PANDA: An icon’s inner carnivore reawakens. | Josh Glenn on FROG: Bumptious ~ Rapscallion ~ Free spirit ~ Palimpsest. | Josh Glenn on MOUSE.

ALSO SEE: John Hilgart (ed.)’s HERMENAUTIC TAROT series | Josh Glenn’s VIRUS VIGILANTE series | & old-school HILOBROW series like BICYCLE KICK | CECI EST UNE PIPE | CHESS MATCH | EGGHEAD | FILE X | HILOBROW COVERS | LATF HIPSTER | HI-LO AMERICANA | PHRENOLOGY | PLUPERFECT PDA | SKRULLICISM.