POST-MICKEY MICE (2)

By:

May 29, 2023

An episode of MOUSE, a multi-part installment in the ongoing BESTIARY series.

During 2021–2022, I contributed three BESTIARY series installments, for each of which I conducted research into and offered a top-line analysis of 20th-century pop-culture depictions of a charismatic creature: OWL | BEAVER | FROG. I first developed this approach for an earlier series, TAKING THE MICKEY, which analyzes Mickey Mouse’s evolving significance. Via this new BESTIARY installment, I’ll “read” Mickey within the context of his fellow pop-culture mice.

This multipart BESTIARY series installment, collectively titled MOUSE, is divided up as follows: MOUSE (INTRO) | PRE-MICKEY MICE (1904–1913) | PRE-MICKEY MICE (1914–1923) | PRE-& POST-MICKEY MICE (1924–1933) | POST-MICKEY MICE (1934–1943) | POST-MICKEY MICE (1944–1953) | POST-MICKEY MICE (1954–1963) | POST-MICKEY MICE (1964–1973) | POST-MICKEY MICE (1974–1983) | POST-MICKEY MICE (1984–1993) | POST-MICKEY MICE (1994–2003).

(1944–1953)

According to HILOBROW’s periodization scheme, the cultural era known as the nineteen-forties begins c. 1944 and ends c. 1953. During this period, let’s see how the mice tropes — surfaced via this audit, and dimensionalized in the series’ introduction — shake out via pop culture.

“The misplaced love of the common people for the wrong which is done them is a greater force than the cunning of the authorities,” Adorno and Horkheimer write in their Dialektik der Aufklärung (Dialectic of Enlightenment), circulated in samizdat form among friends and colleagues in 1944. “It calls for Mickey Rooney in preference to the tragic Garbo, for Donald Duck instead of Betty Boop. … The conformism of the buyers and the effrontery of the producers who supply them prevail. The result is a constant reproduction of the same thing.”

Mickey Rooney and Donald Duck — Mickey Mouse is the unspoken third point of this triangle — represent the bland, inoffensive, churned-out product of the factory-like Culture Industry, while Greta Garbo and Betty Boop represent truly popular culture — weird, alluring, eccentric, original and incommensurable. Already, at the very beginning of the Forties (1944–1953, according to HILOBROW’s periodization), Adorno and Horkheimer are lamenting that (to quote David Bowie) Mickey Mouse has grown up a cow.

Adorno is frequently dismissed — by folks across the political spectrum — as a mandarin, i.e., an elitist who hates pop culture. In fact, he applauded unique and eccentric lowbrow productions, from circuses to peepshows — which he described as being every bit as “embarrassing” to the coercive aims of the American culture industry as are those highbrow works (e.g., Schoenberg) for which he is a better-known advocate. As we can see from the passage quoted above, he’s not anti-cartoon. Adorno digs Betty Boop — Max Fleischer’s anthropomorphic French poodle and sex symbol — who was hailed as the “queen of the animated screen” from 1930–1939. What he doesn’t dig is the calculated cuteness and pseudo-eccentricity of Disney’s characters — as they’d evolved from their weirder, gutsier, Boop-like origins due to market pressure. He’s right!

“A Dork Age,” according to TV Tropes, “is a period in a franchise, especially a long-running one, where there was a dramatic change of concept or execution, usually to stay current and it did not work.”

In previous installments in this series, we’ve noted how Mickey rapidly evolved from a minstrel-ish, prankster-ish figure into an iconic role model who, by the end of the Thirties (1934–1943, according to HILOBROW’s periodization schema), had been eclipsed by Donald Duck. Disney’s attempt to resuscitate Mickey’s appeal among moviegoers by giving him a starring role in Fantasia (1940) was a failure.

Throughout the cultural era known as the Forties (1944–1953), Mickey was a friendly, well-meaning everyman. Although the character continue to appear regularly in shorts in the latter half of the Forties, Mickey’s popularity steadily plummeted.

After 1943’s Pluto and the Armadillo, Mickey no longer wears red shorts. He has grown up — into a model citizen, an everyman. An “everyman” is a character without any intrinsic personality onto whom audience members are invited to project themselves. MM is depicted as just such a figure, from 1944–1953. He is a Mouse Without Qualities.

Disney gave up on using Mickey in movies after The Simple Things (1953), a typically lame outing in which Mickey is bested not only by a seagull but a mollusk. (“By 1953, last cartoon,” sighs Stephen Jay Gould in his essay “A Biological Homage to Mickey Mouse,” “he has gone fishing and cannot even subdue a squirting clam.”) Please note how precisely the date of MM”s last movie coincides with our periodization schema!

Whimsy had triumphed over wit, sentimentality over emotion. Mickey’s rough edges had been sanded off entirely — he no longer had any sort of personality. He’d become a textbook illustration of T.W. Adorno’s warning that qualitatively unique individuals were being transformed into quantitatively fungible components of the social machine. The modern subject, worried Adorno, is a pseudo-individualized automaton who’s been “reduced to the nodal point of the conventional responses and modes of operation expected of him.” More on Adorno in the next installment….

So it’s interesting to see other mice playing aspects of the role that MM abdicated, during the Forties…

Adventure Comics #105 — June 1946. From a story called “The Knight’s Gambit!”

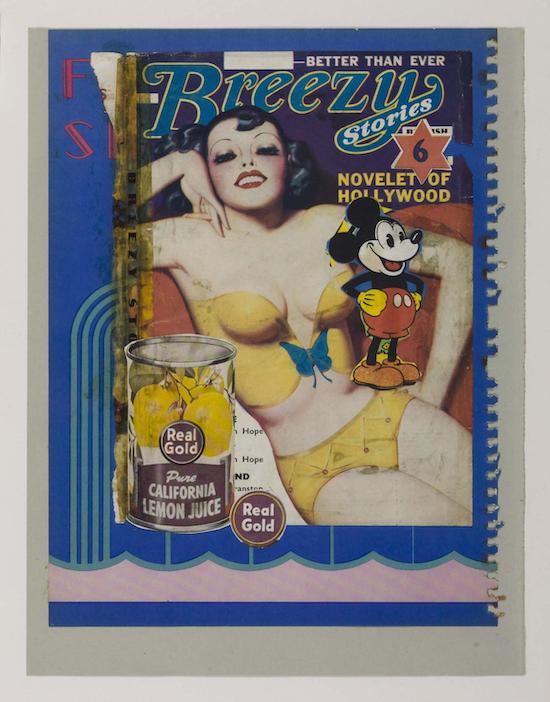

Between 1948 and 1952, English artist Eduardo Paolozzi pasted together a series of small collages — collectively titled BUNK — a couple of which featured Mickey and Minnie Mouse juxtaposed with, e.g., idealized representations of movie stars, fruit, and tuna cans from American magazines (given to the artist by American servicemen). Paolozzi’s mingled fascination with and distaste for the products of American consumer culture paved the way for the Pop Art movement.

Shown above: Real Gold (1950). Note that Paolozzi is drawn to the MM of the Thirties; not the insipid MM of the Forties.

I include this example in the ABJECT OTHER category because MM is used as a lowbrow icon in a highbrow context for shock value… We’ll see this recontextualizing maneuver again, from other artists who long for MM to once more become… a rebellious scamp, a scrappy survivor, etc.

In Cinderella (1950), the newly arrived mouse Gus is trying to hide from Lucifer. His hiding spot turns out to be under Anastasia’s teacup, causing her to scream in terror and accuse Cinderella of putting a “big ugly mouse” on her tea tray on purpose.

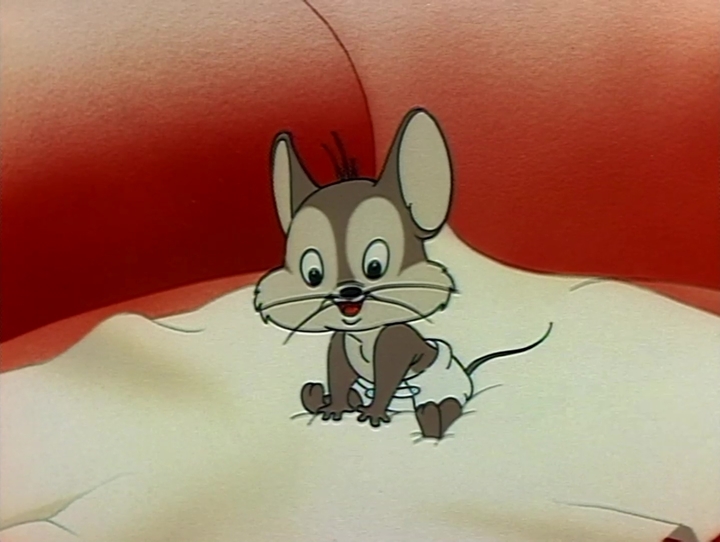

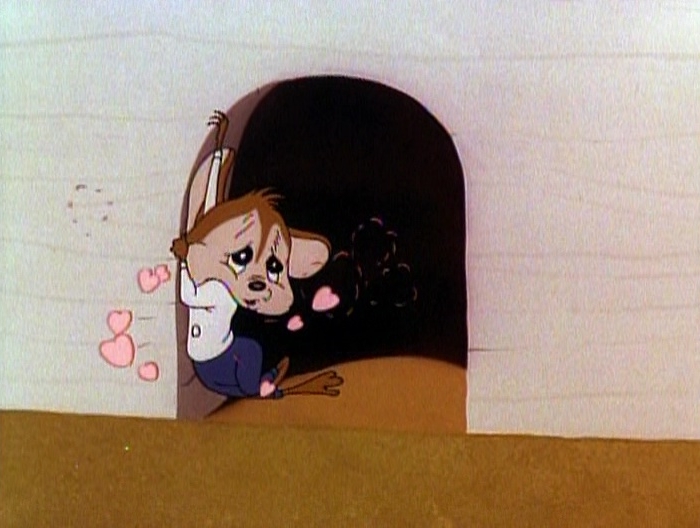

A Mouse Divided is a 1953 Merrie Melodies animated short directed by Friz Freleng. A drunken stork drops a baby mouse off at Sylvester’s house. He raises it as his own — but must protect his foster child vs. other cats.

I include this example in the ABJECT OTHER category although the mouse is not frightening/disgusting. (Quite the contrary: It’s extremely cute.) However, it is an alien invader, very much out of place. One could almost “read” this short as cynical commentary on how Mickey Mouse captured America’s heart…. (See previous installment in this series.)

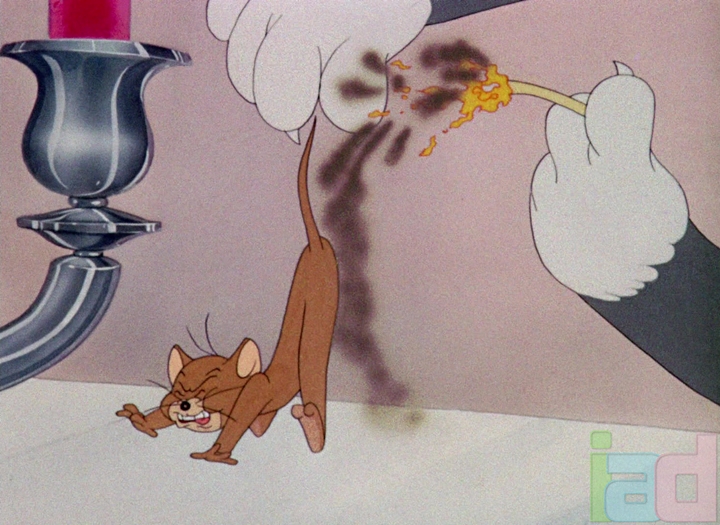

Tom invites Toots to an elegant dinner. However, he’s made the mistake of trying to put Jerry to work, as a serving boy, a corkscrew, and other tasks. Jerry puts up with a little of this, but mostly gets revenge on Tom, mostly involving the tip of Tom’s tail, which ends up in a sandwich, inside a dessert, and in a candle-holder.

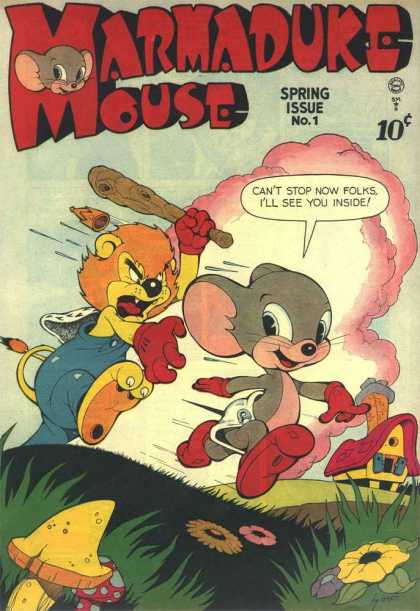

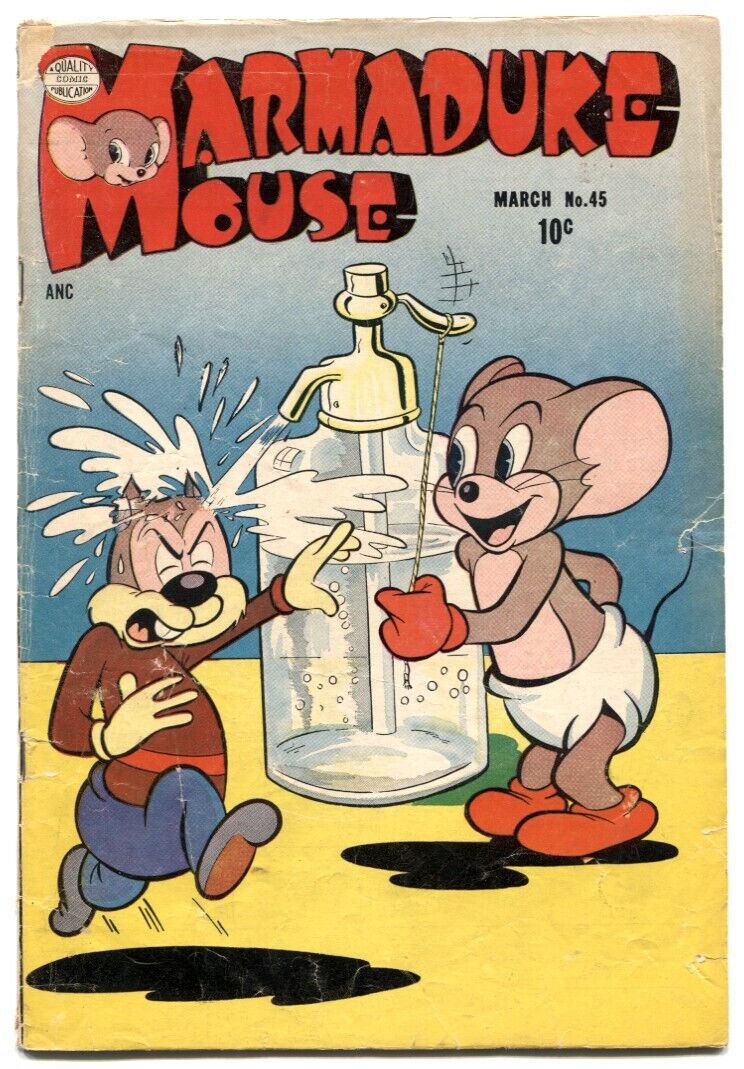

Quality Comics, which published comic books of quality from the late 1930s to the middle ’50s, is best known for The Spirit, Blackhawk, Plastic Man, and other action/adventure titles. However, one of its longest-lasting titles was Marmaduke Mouse, which featured stories of yet another alliterative MM.

He worked for King Louie, a lion, doing odd jobs — which included anything from cutting the lawn to getting the king out of truly extraordinary jams. Apparently, his position was something along the lines of head minion or lackey-in-chief. The most striking (in fact, only distinguishing) thing about Marmaduke’s appearance was that he always wore a diaper.

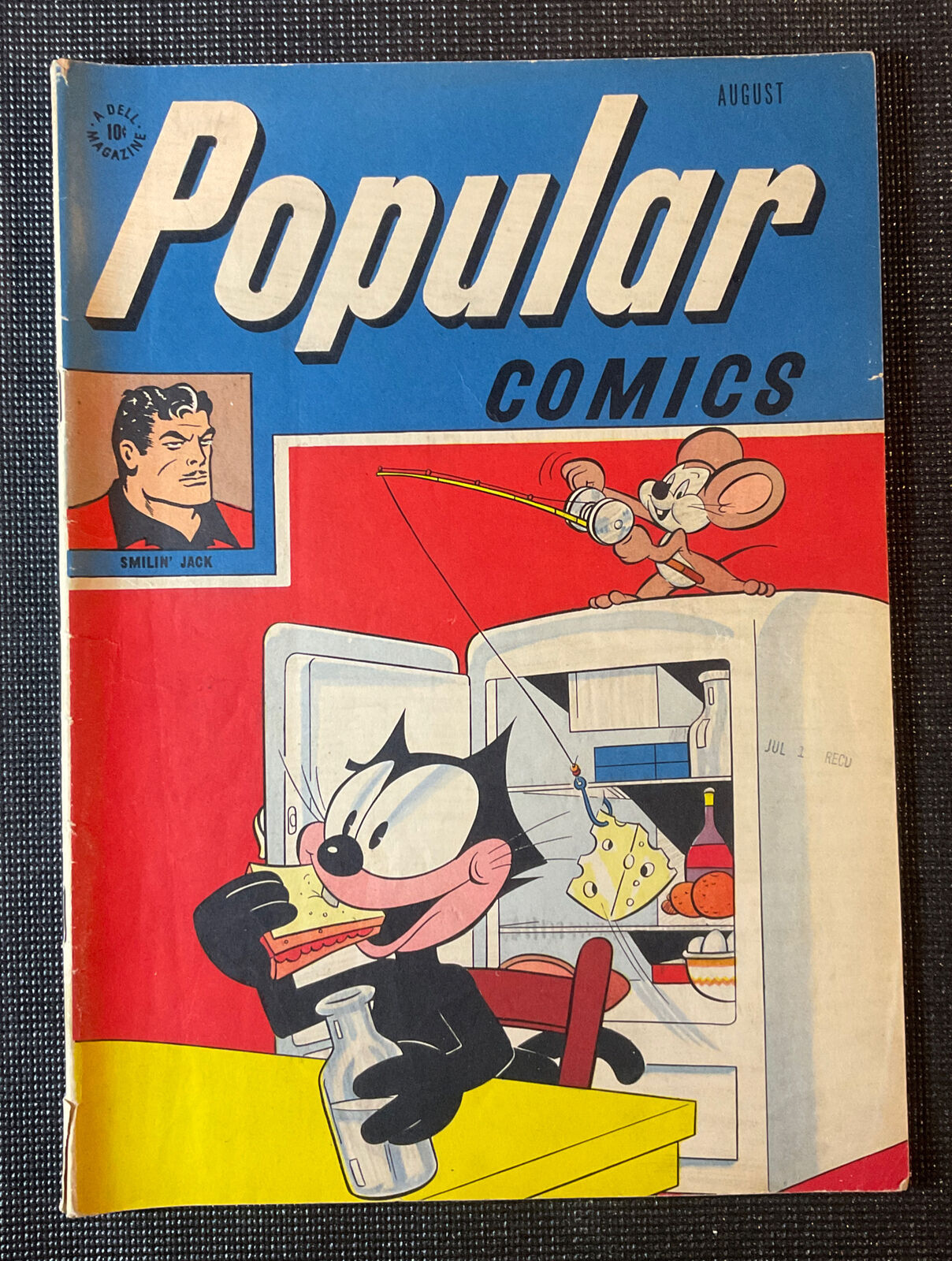

Popular Comics #138 (1947) Dell Comics.

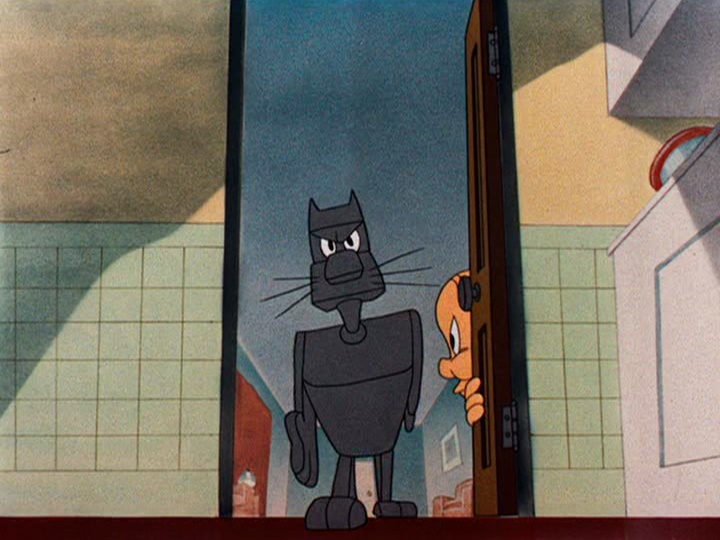

“Scaredy Cat” is a 1948 Looney Tunes cartoon short featuring Sylvester and Porky Pig directed by Chuck Jones. The plot begins with Porky Pig and his pet cat Sylvester arriving at their new house in the middle of the night, which Sylvester finds scary. But as the unfazed Porky only wants to get a good night’s sleep, the easily frightened Sylvester discovers that a cult of murderous mice inhabit their new house, having recently executed the cat belonging to the previous homeowners, and plan to make the new owners their next victims.

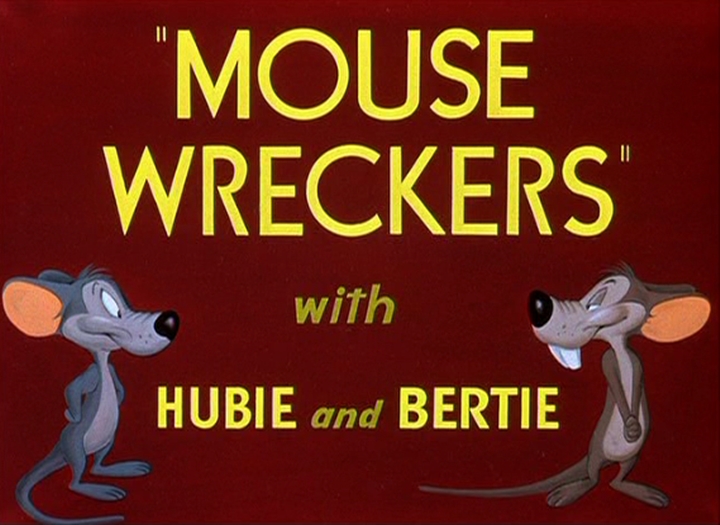

Mouse Wreckers is a 1949 Warner Bros. Looney Tunes short directed by Chuck Jones, written by Michael Maltese and starring Hubie and Bertie in their first pairing with the redesigned Claude Cat.

Hubie comes up with several ways to chase Claude out, all of which are designed to drive him crazy, having Bertie do each of the tricks.

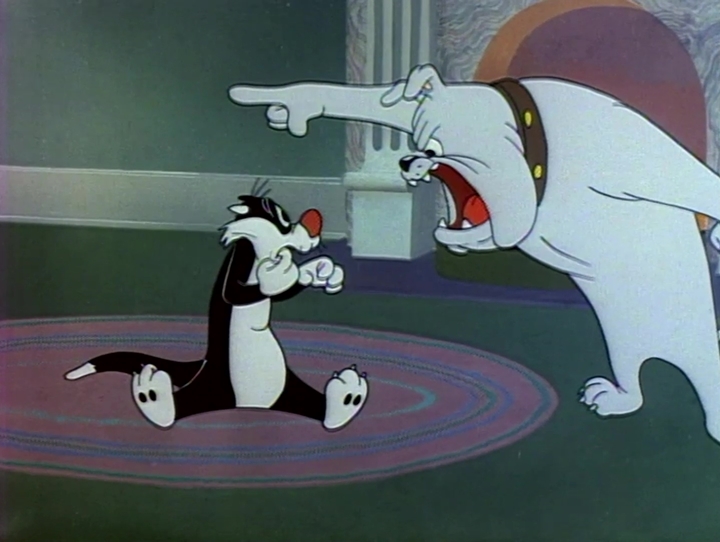

A hungry mouse starts stirring up trouble, after hearing Sylvester call the bulldog “Mike.” For example, it leaves telephone earpiece by the sleeping Mike’s ear, and insinuates that Sylvester only wants Mike as “its pillow.” He also calls to say the that other dogs are laughing at him, because he likes Sylvester. After successfully turning the two friends into enemies, the mouse makes its move…

Herman the Mouse and Katnip the Cat starred in theatrical animated shorts produced by Famous Studios in the 1940s and 1950s. From 1944 to September 1950, Herman was a solo star of theatrical animation shorts. Katnip made his first appearance in November 1950 with “Mice Meeting You.”

Leonard Maltin described the Herman and Katnip series as a prime stereotype of the “violent cat versus mouse” battles that were commonplace among Hollywood cartoons of the 1920s through the 1960s. All of Herman’s battles with Katnip ended with Herman victorious. The Simpsons writer/producer Mike Reiss claims The Itchy & Scratchy Show is based on Herman and Katnip.

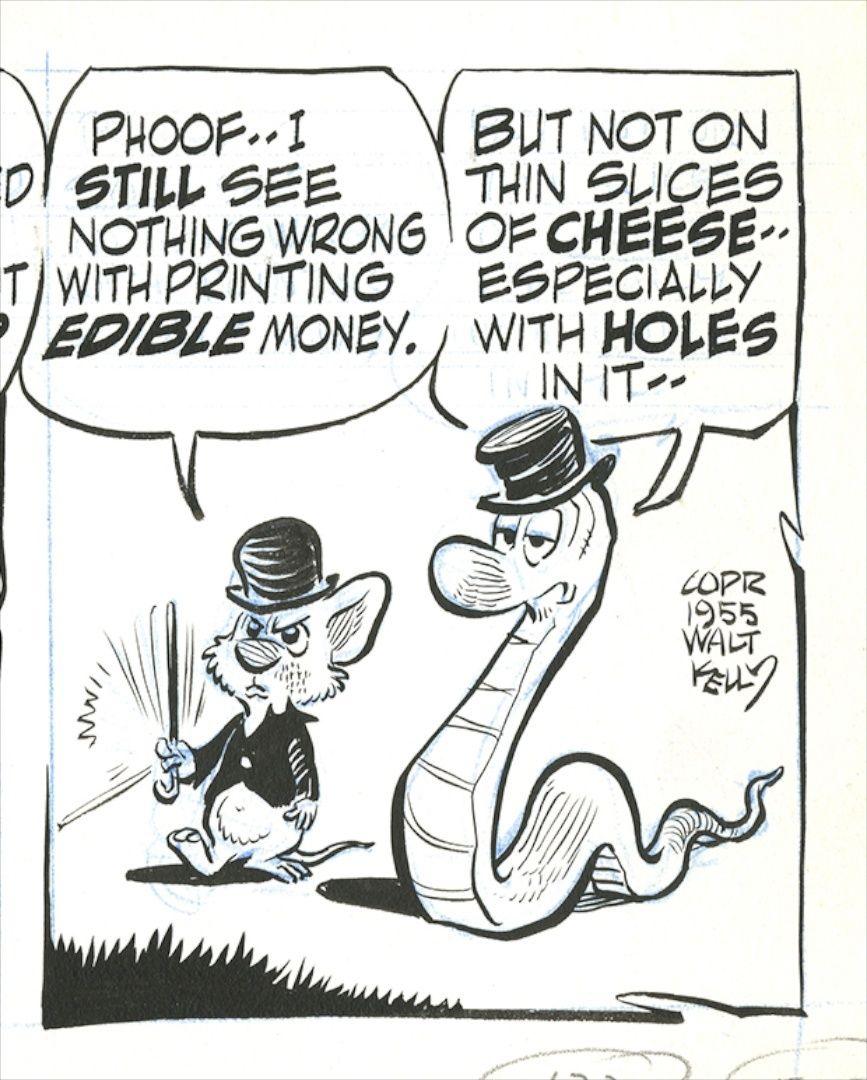

Ol’ Mouse — a long-winded, worldly mouse with a bowler hat, cane and cigar who frequently pals around with Snavely, the Flea, Albert, or Pup Dog — first appeared in Walt Kelly’s Pogo strip in 1950. He has a long and storied career as a rogue, in which he takes some pride, noting that the crimes he has been falsely accused of are far less interesting than the crimes he has actually committed. Something of a dandy, he sometimes takes the name ‘F. Olding Munny.’

Terrytoons’s Little Roquefort makes his first appearance in 1950. He is a small but fiery little rodent always looking for fun, food, or a chance to relax, but unluckily for him, he is constantly pestered by a bothersome pussycat named Percy.

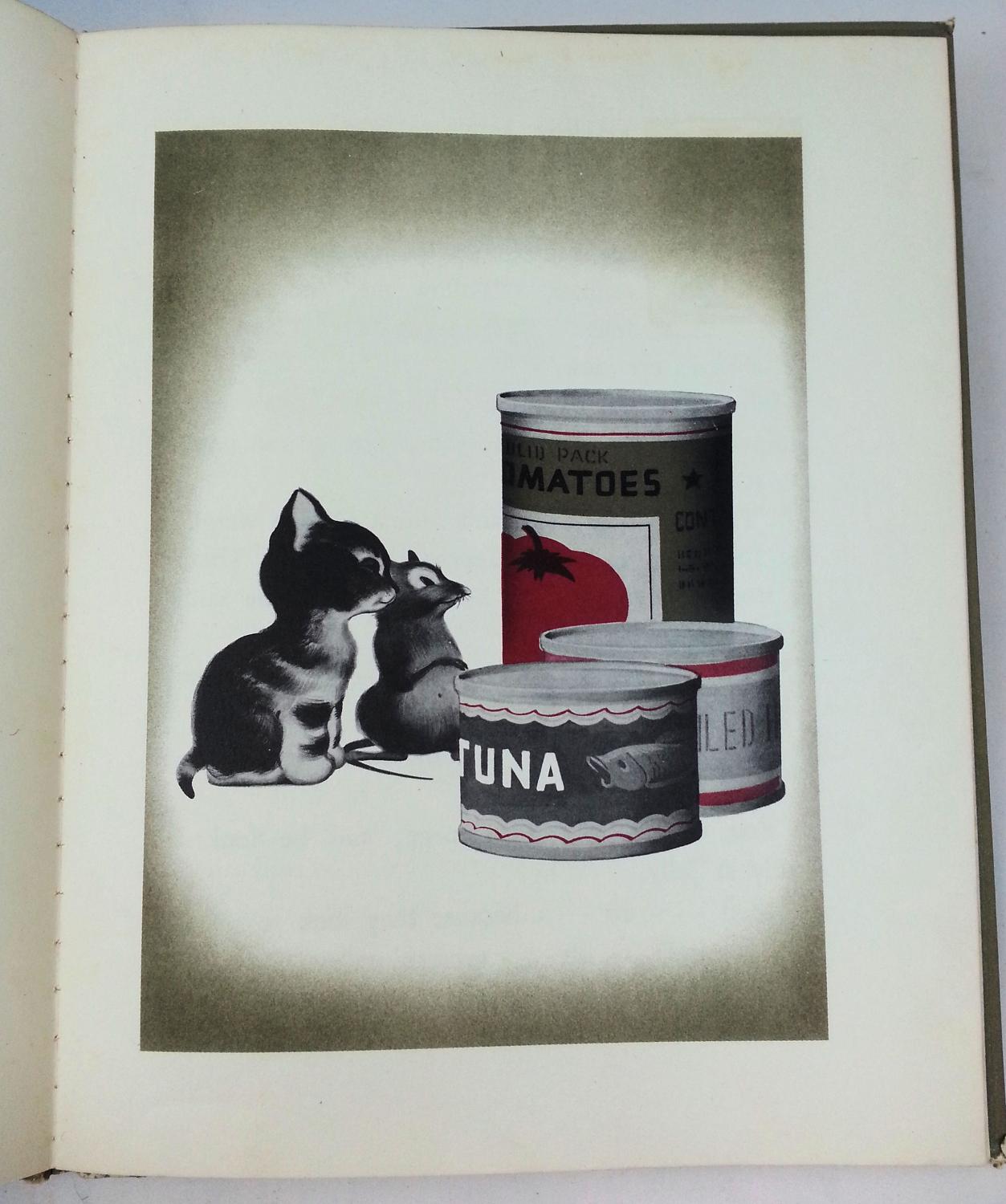

“Canned Feud” is a 1951 Looney Tunes starring Sylvester the Cat. It was directed by Friz Freleng.

Sylvester is left at home when his owners leave for a California vacation. They completely forget to put him out and didn’t leave food out for Sylvester before they go. Luckily for Sylvester, he finds a large collection of canned food. Unluckily for Sylvester, the only can opener is in the possession of a mouse who doesn’t want to give it up. The rest of the cartoon consists of the mouse tormenting Sylvester as he tries to obtain the opener.

A rebellious scamp, and yet another alliterative MM.

Snow Business is a 1953 Warner Bros. Looney Tunes cartoon directed by Friz Freleng. Sylvester and Tweety are alone in Granny’s mountain cabin. The radio reports that the roads will be blocked for six weeks. Panicked, Sylvester looks for food everywhere finding nothing but bird seed. While Sylvester and Tweety are initially friends in the short, Sylvester attempts to eat Tweety, tricking him into thinking various cooking methods are games, to which Tweety is oblivious. The Sylvester-chases-Tweety cycle is continually disrupted by a mouse who is even hungrier and more desperate than Sylvester, the mouse seizing upon the idea of eating Sylvester.

A white mouse escapes from an experimental laboratory, after consuming enough of a new secret explosive to blow up an entire city. Meanwhile, Jerry Mouse has been accidentally doused with white shoe polish…

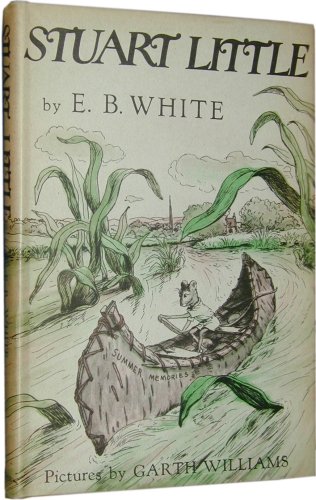

Stuart Little, titular hero of E.B. White’s 1945 children’s novel (ill. Garth Williams), is a mouse born to a human family. He races a sailboat in Central Park, gets shipped out to sea in a garbage can, and sets out — several years before Kerouac’s On the Road — on a cross-country odyssey. The book was criticized, at the time, by the New York Public Library’s influential children’s lit expert for being nonaffirmative, inconclusive, and unfit for kids.

One day Aunt Mathilda the Mouse puts a big piece of cheese in her apron Pocket and starts off to the red barn to visit her nieces and nephews. When she arrived at the barn, she found to her dismay that the cheese is gone. Here is the story of poor Aunt Mathilda’s adventures on her search for the lost cheese. Author: Muriel Laskey. I think 1946.

Technically Mathilda Mouse is another alliterative MM.

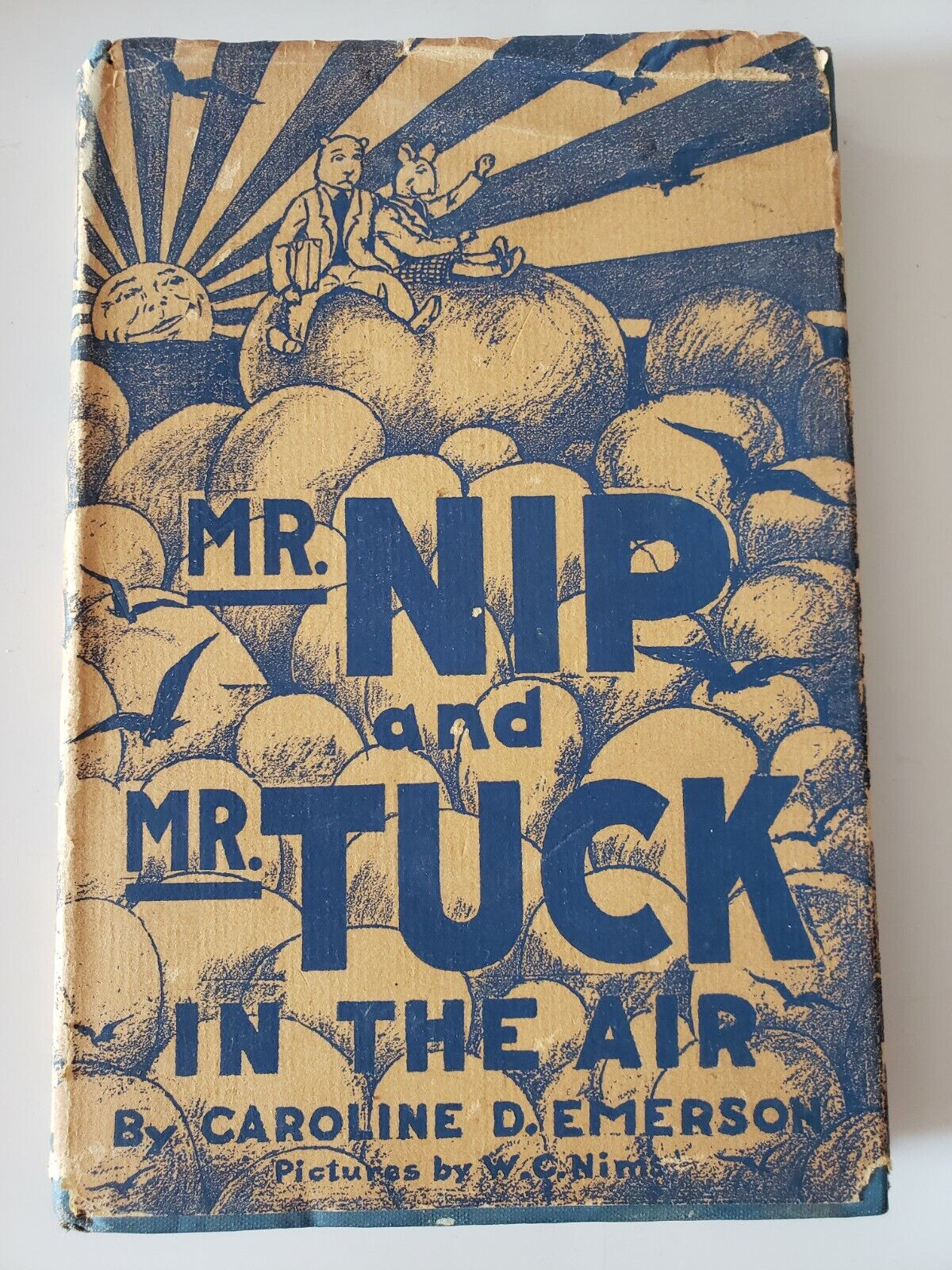

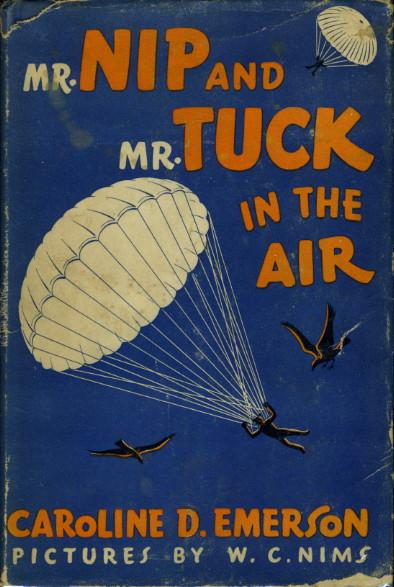

1946 book. Mr Nip (who resembles a mouse) and Mr Tuck (who looks a bit like a teddy bear and a bit like a cat) have an aerial adventure. In this book, the charming illustrations are by W. C. Nims but are based (with her consent) on the original figures drawn by Lois Lenski.

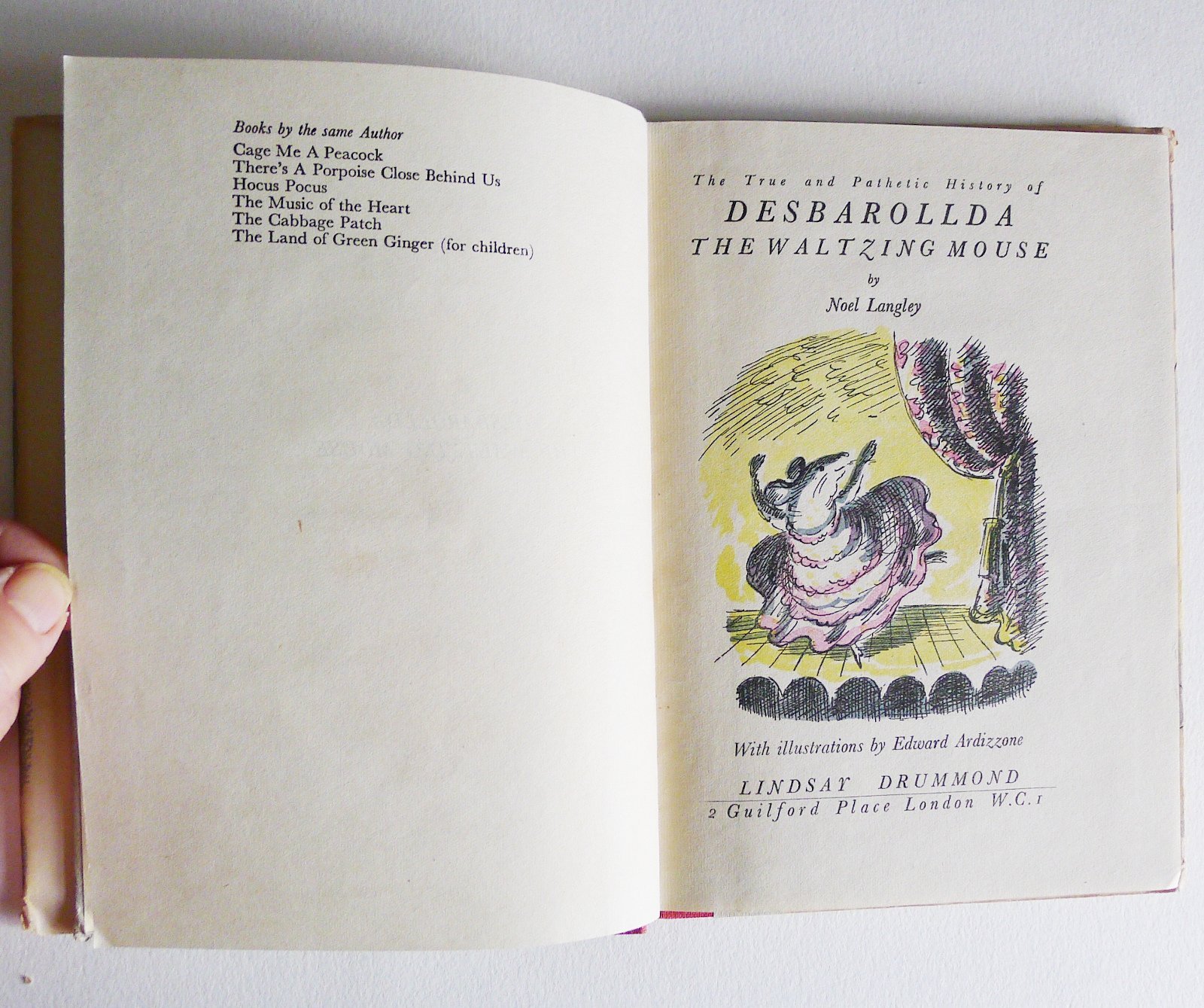

The True and Pathetic History of Desbarollda, The Waltzing Mouse (1947) by Noel Langley. Illustrated by Edward Ardizzone.

Reepicheep appears as a minor character in C.S. Lewis’s Narnia book Prince Caspian (1951), and as a major character in The Voyage of the Dawn Treader (1952), and also briefly at the end of The Last Battle (1956). The leader of Narnia’s Talking Mice, the swashbuckling Reepicheep is irascible yet gallant, utterly fearless, and motivated by a deep concern for honor (and his tail); he is perhaps Lewis’s most entertaining character.

Speedy Gonzales is an animated cartoon character in the Warner Bros. Looney Tunes and Merrie Melodies series of cartoons. He is portrayed as “The Fastest Mouse in all Mexico” with his major traits being the ability to run extremely fast, being quick-witted and heroic while speaking with an exaggerated Mexican accent.

Speedy’s first appearance was in 1953’s Cat-Tails for Two though he appeared largely in name (and super speed) only. It would be two years before Friz Freleng and layout artist Hawley Pratt redesigned the character into his modern incarnation for the 1955 Freleng short of the same name. The cartoon features Sylvester the Cat guarding a cheese factory at the international border between the United States and Mexico from starving Mexican mice. The mice call in the plucky, excessively energetic Speedy (voiced by Mel Blanc) to save them.

Feeling that the character presented an offensive Mexican stereotype, Cartoon Network shelved Speedy’s films when it gained exclusive rights to broadcast them in 1999. However, Speedy Gonzales remained a popular character in Latin America. Many Hispanic people remembered him fondly as a quick-witted, heroic Mexican character who always got the best of his opponents.

Eleanor Clymer and Jeanne Bendick’s The Grocery Mouse (1945). Squeaker the mouse lives in a grocery store with his family. When he ventures into the store in the daytime, he meets the mouse Saltina. The two are chased outdoors by a cat, and have many adventures out in the world before returning to the safety of the grocery store.

Fritz Wilis children’s book.

Porky has a particularly menacing mouse in his house; after his traps, and an increasingly nasty set of cats all fail, Porky builds a robot cat. This cat proves to be a much bigger challenge for the mouse, who ultimately builds a robot mouse packed with explosives.

Mouse-Warming is a 1952 Warner Bros. Looney Tunes short, directed by Chuck Jones

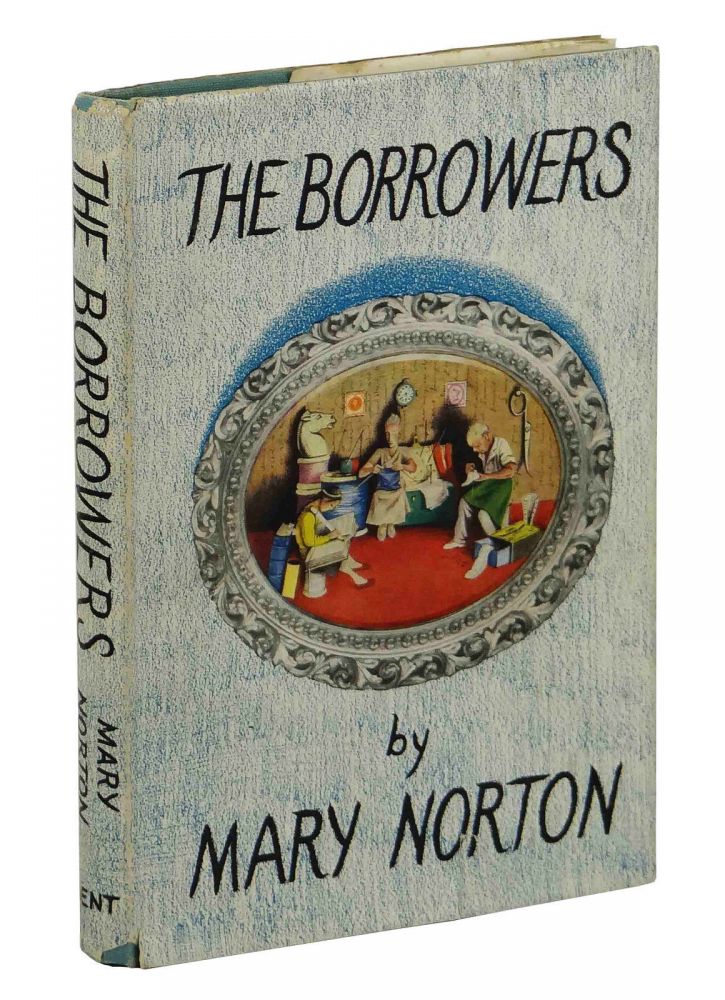

The Borrowers is a children’s fantasy novel by the English author Mary Norton, published in 1952. It features a family of tiny people — the Clock family; Pod, Homily and Arrietty — who live secretly in the walls and floors of an English house and “borrow” from the big people in order to survive. It was published in the U.S. in 1953 with illustrations by Beth and Joe Krush.

The primary cause of trouble and source of plot is the interaction between the minuscule Borrowers and the “human beans”, whether the human motives are kind or selfish. The main character is teenage Arrietty, who often begins relationships with Big People that have chaotic effects on the lives of herself and her family, causing her parents to react with fear and worry.

The sequels are titled alliteratively and alphabetically: The Borrowers Afield (1955), The Borrowers Afloat (1959), The Borrowers Aloft (1961), and The Borrowers Avenged (1982).

A. N. Wilson considered the first book as in part an allegory of post-war Britain – with its picture of a diminished people living in an old, half-empty, decaying “Big House.”

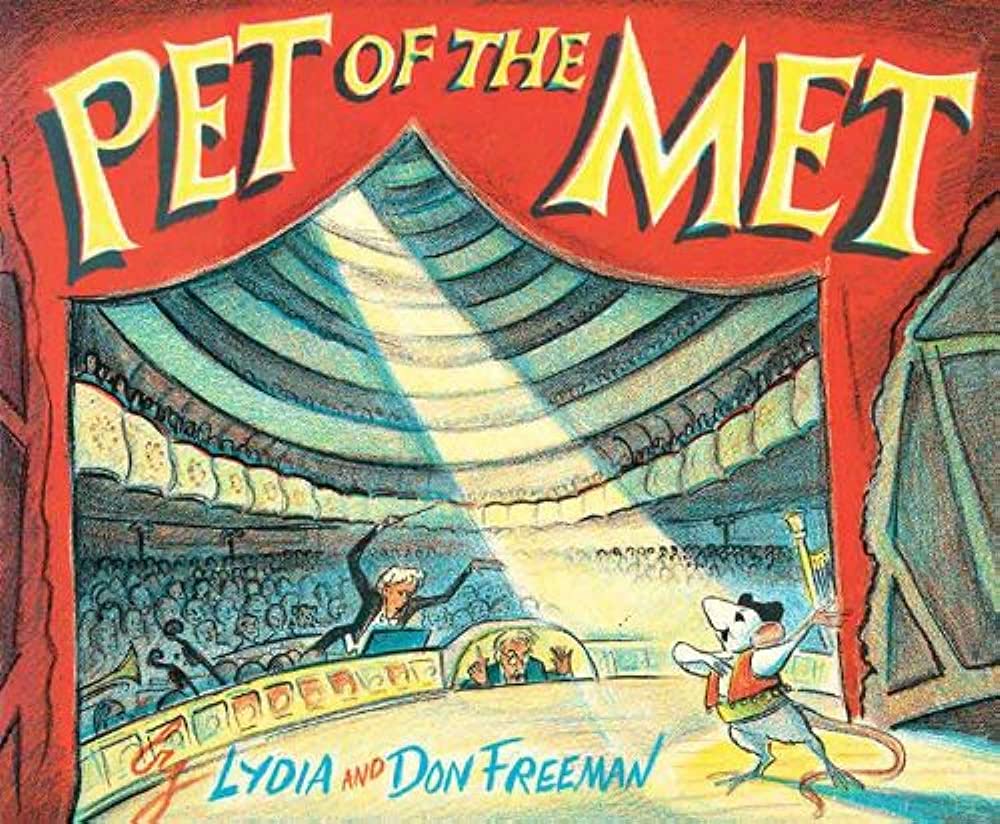

Maestro Petrini is the only mouse at the Metropolitan Opera House, the perfect place for a music loving mouse and his family. The only danger is Mefisto, the opera house cat, who hates music and mice — until one day when he listens to The Magic Flute and becomes enlightened.

Maestro [the mouse] — subtly alliterative.

1944 advertisement.

Anchors Aweigh is a 1945 American musical comedy film starring Frank Sinatra, Kathryn Grayson, and Gene Kelly. The plot concerns two sailors on a four-day shore leave in Hollywood. In a live-action/animated fantasy sequence, Kelly dances with Jerry Mouse (of Tom and Jerry fame).

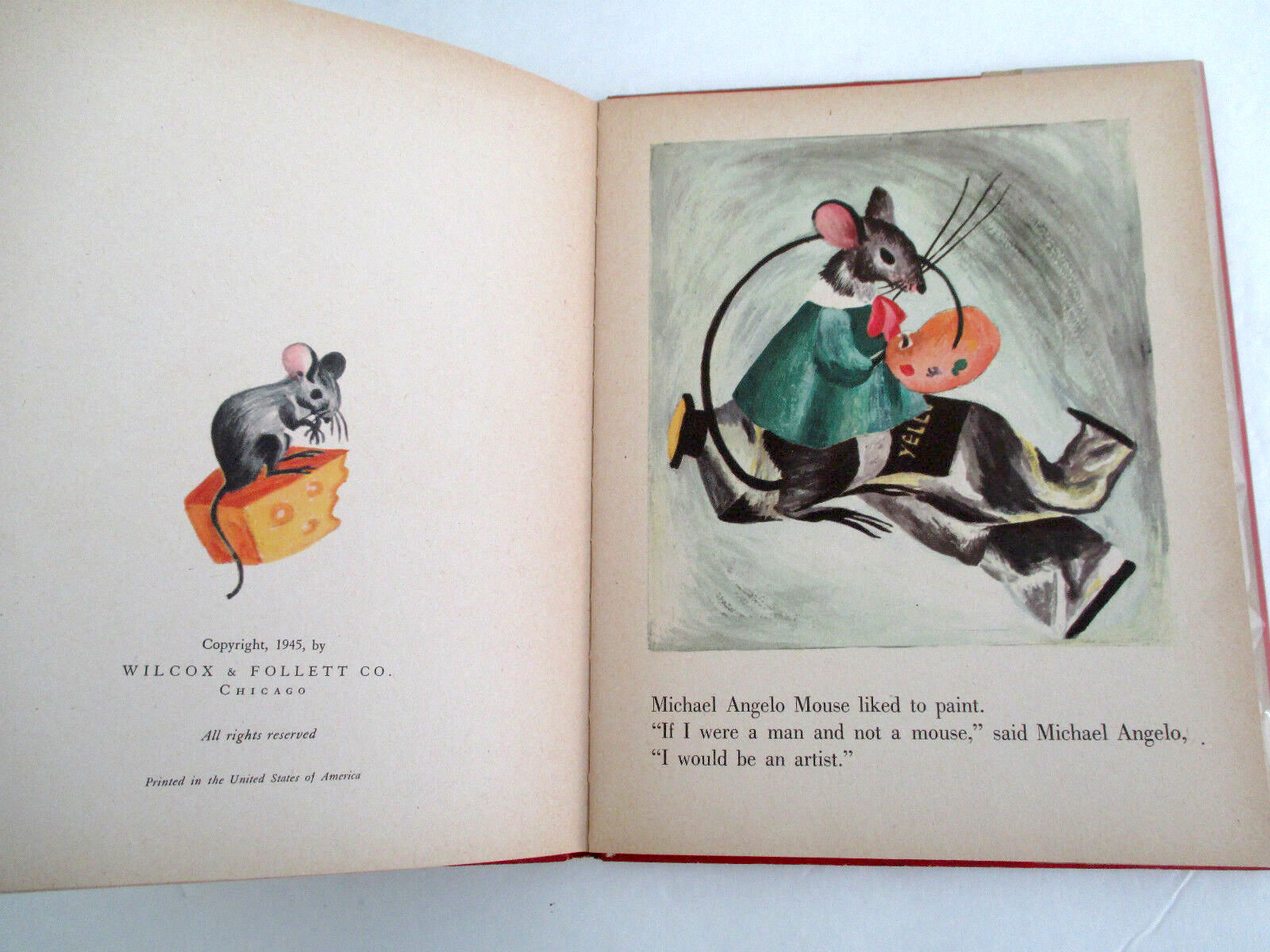

Michael Angelo Mouse (1945) by Katherine Evans. He lives with a human artist whose work isn’t selling, so there’s never enough to eat in the house. But one day, the artist falls asleep, leaving his paints and a blank canvas…

Another alliterative MM.

See Paolozzi’s use of a different MM in a fine art context, in ABJECT section.

The primary subject taught in Mouse School is Cat Identification. One little mouse announces he doesn’t know what a cat is and has never seen one. Meanwhile, Mr. Cat has found his way into the classroom, but the dumb little mouse stands up and challenges him, which gives the other little mice the courage to a concerted attack against the cat.

Clearly there is an anti-fascist aspect to I. Sparber’s animated short for Paramount.

In Cinderella (1950), the mice are quite ingenious in their abilities to help Cinderella. Jaq and Gus get a whole necklace of beads from the stepsisters’ room to Cinderella’s by stringing them on their tails (while evading Lucifer the cat the entire time). Meanwhile the female mice rig up a pulley system with the friendly bluebirds to sew her dress.

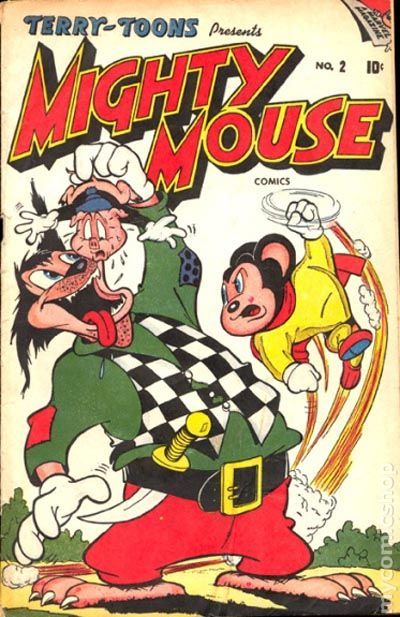

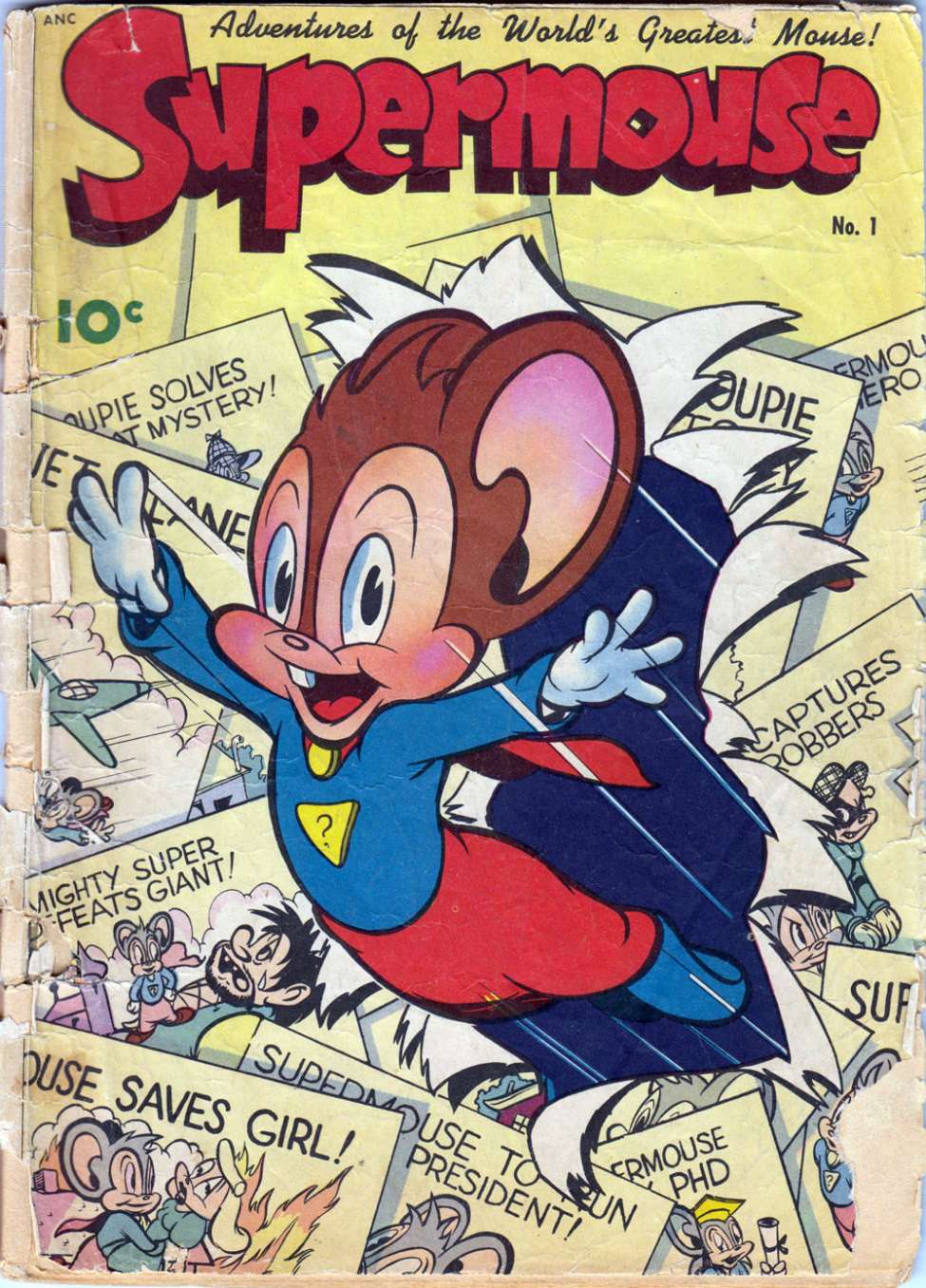

First time as comedy, second time as tragedy. Mighty Mouse was originally a Superman parody… before he became a superhero in earnest. [See previous installment.] Below we’ll see more variations on this theme…

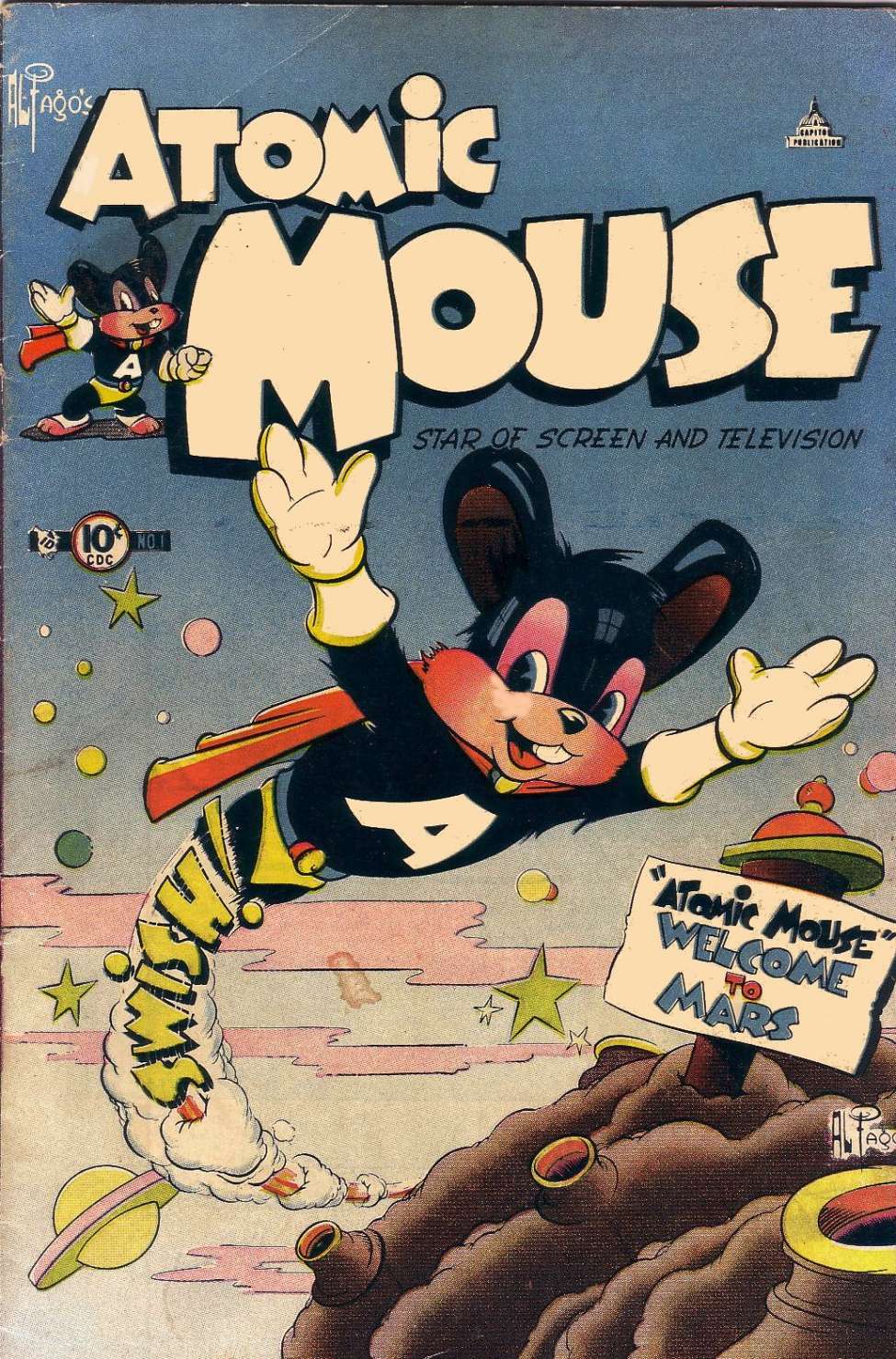

Atomic Mouse is a funny animal superhero created in 1953 by Al Fago for Charlton Comics, depicted as an ordinary mouse who is shrunk by an evil magician and given U-235 pills that grant him super powers, which he uses in his fight for justice against the evil Count Gatto. The strip bearing his name ran to 54 issues over eleven years, and many of his stories were reprinted during the mid-1980s by the American Comics Group.

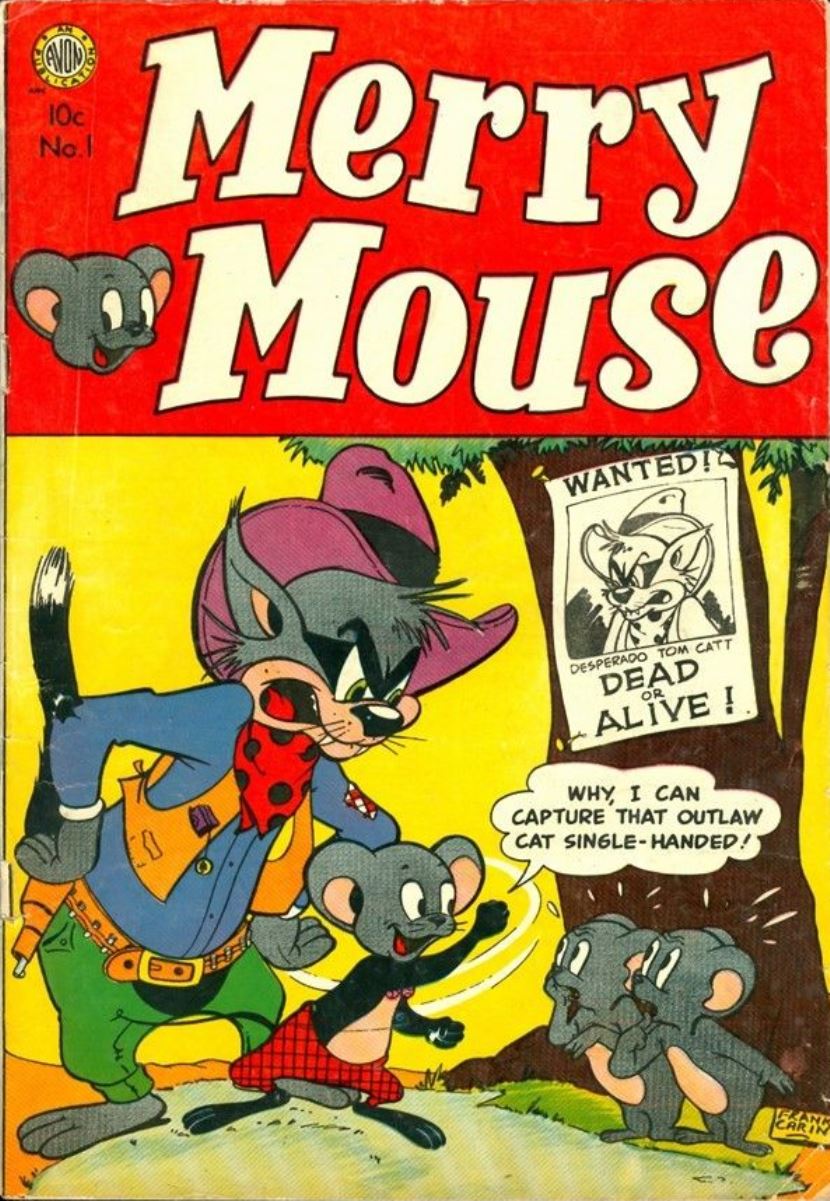

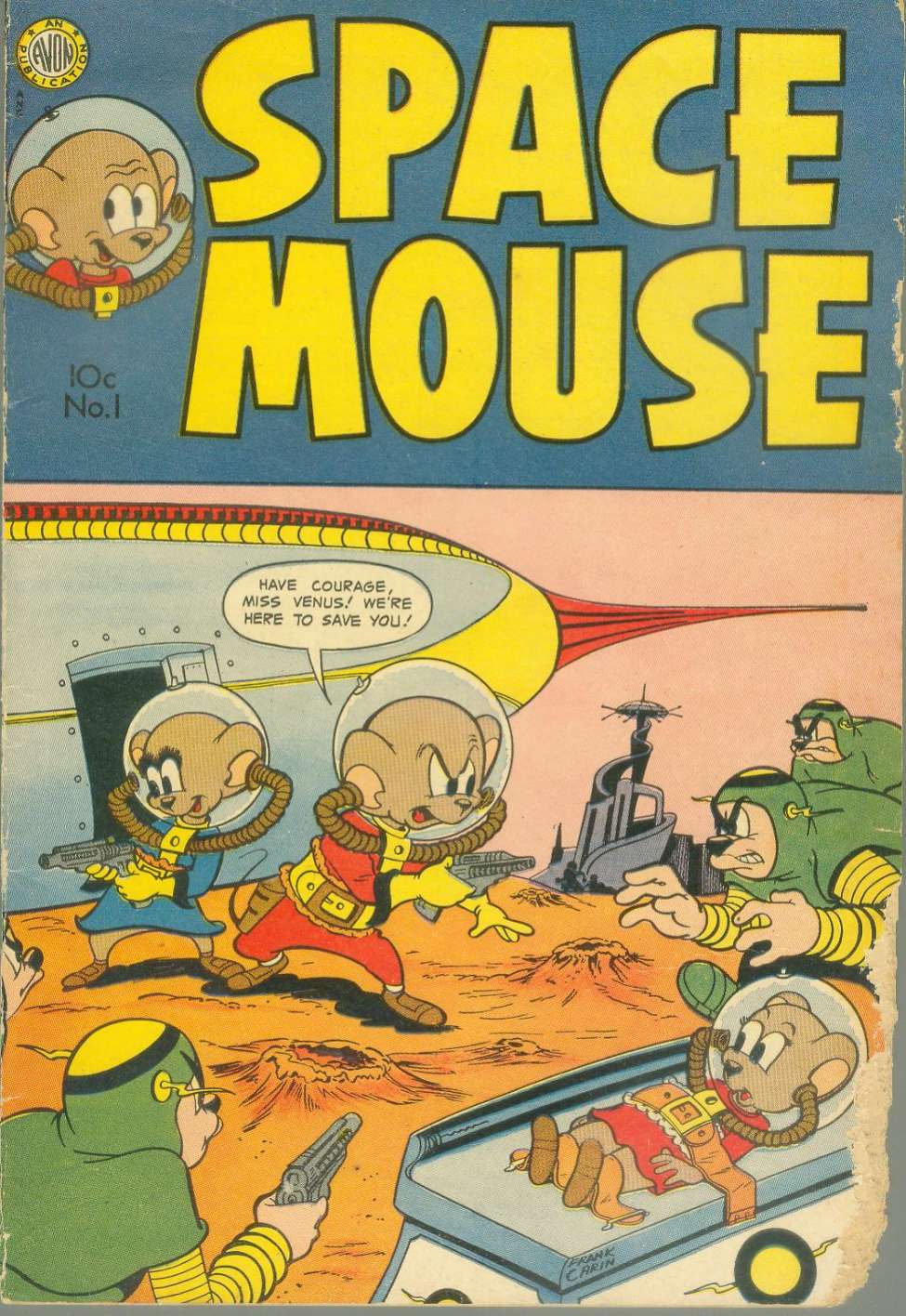

The first Space Mouse was a comic book character published from 1953 to around 1956 by Avon Publications.

The introductory story of Space Mouse is entitled “The Great Electro!” A large, brutish cat named Electro calls Earth from Mercury. He informs Space Mouse that a group of Earth’s explorers had landed on Mercury, and have been captured and are being held prisoner. They will be held as slaves as a warning to the rest of Earth. Space Mouse and his girlfriend Millie head off to Mercury in the hero’s rocket ship.

The last story in that first issue, “Atomic Attack!”, appears to be the earliest chronological adventure of Space Mouse (the hero shows Millie a rocket ship which he has just built, which is the same rocket ship used in the previous stories). In this tale, Space Mouse and Millie notice a strange growth in the backyard and discover that it is being caused by an atomic ray from Mars. Space Mouse believes that the whole Earth will be covered with the growth, choking off all forms of life. The hero takes Millie to the roof and shows her a new rocket ship that he has built, which they will take to Mars.

PS: See the following installment in this series for two additional Space Mouse characters. Space Mouse is the name of a 1959 Universal Studios cartoon featuring two mice and a cat named Hickory, Dickory, and Doc. And another Space Mouse character was published by Dell Comics / Gold Key Comics from 1960–1965.

The Lion, the King of the Jungle, is taking his royal snooze when a mouse comes on a safari to his royal hideaway. The mouse is from Bungling Brothers Circus and his mission is to take HRH back to the USA as a circus act….

Not nearly as popular a trope during this era it is was previously.

Mouse in Manhattan is a 1945 one-reel animated cartoon and is the 19th Tom and Jerry short. Jerry has enough of the country life and decides to leave for the city. He writes a goodbye letter to Tom saying he’s off to see the city of lights. In a series of antics in Manhattan, he gets stuck in gum on the floor of Grand Central, ends up as a makeshift shoe-polisher, admires the towering skyscrapers, attempts to climb the Empire State Building, etc.

There is a blackface moment — boo.

The short ends with Jerry nailing a sign reading “Home Sweet Home” above his mousehole, and entering afterwards, choosing to remain in the countryside.

Louise Andrews Kent’s Country Mouse (1945) is a forgotten gem in the “home front” genre of literature. It describes with humor and delicacy the trials of the women left behind in the USA while their men were off fighting. Socialite Marcella Carmody decides to start an artists’ colony in Vermont. Part exercise in social climbing, part fund-raising effort, the colony attracts a strange mix of artists, poseurs and refugees.

INTRODUCTION by Matthew Battles: Animals come to us “as messengers and promises.” Of what? | Matthew Battles on RHINO: Today’s map of the rhinoceros is broken. | Josh Glenn on OWL: Why are we overawed by the owl? | Stephanie Burt on SEA ANEMONE: Unable to settle down more than once. | James Hannaham on CINDER WORM: They’re prey; that puts them on our side. | Matthew Battles on PENGUIN: They come from over the horizon. | Mandy Keifetz on FLEA: Nobler than highest of angels. | Adrienne Crew on GOAT: Is it any wonder that they’re G.O.A.T. ? | Lucy Sante on CAPYBARA: Let us gather under their banner. | Annie Nocenti on CROW: Mostly, they give me the side-eye. | Alix Lambert on ANIMAL: Spirit animal of a generation. | Jessamyn West on HYRAX: The original shoegaze mammal. | Josh Glenn on BEAVER: Busy as a beaver ~ Eager beaver ~ Beaver patrol. | Adam McGovern on FIREFLY: I would know it was my birthday / when…. | Heather Kapplow on SHREW: You cannot tame us. | Chris Spurgeon on ALBATROSS: No such thing as a lesser one. | Charlie Mitchell on JACKALOPE: This is no coney. | Vanessa Berry on PLATYPUS: Leathery bills leading the plunge. | Tom Nealon on PANDA: An icon’s inner carnivore reawakens. | Josh Glenn on FROG: Bumptious ~ Rapscallion ~ Free spirit ~ Palimpsest. | Josh Glenn on MOUSE.

ALSO SEE: John Hilgart (ed.)’s HERMENAUTIC TAROT series | Josh Glenn’s VIRUS VIGILANTE series | & old-school HILOBROW series like BICYCLE KICK | CECI EST UNE PIPE | CHESS MATCH | EGGHEAD | FILE X | HILOBROW COVERS | LATF HIPSTER | HI-LO AMERICANA | PHRENOLOGY | PLUPERFECT PDA | SKRULLICISM.