PRE- AND POST-MICKEY MICE

By:

April 30, 2023

An episode of MOUSE, a multi-part installment in the ongoing BESTIARY series.

During 2021–2022, I contributed three BESTIARY series installments, for each of which I conducted research into and offered a top-line analysis of 20th-century pop-culture depictions of a charismatic creature: OWL | BEAVER | FROG. I first developed this approach for an earlier series, TAKING THE MICKEY, which analyzes Mickey Mouse’s evolving significance. Via this new BESTIARY installment, I’ll “read” Mickey within the context of his fellow pop-culture mice.

This multipart BESTIARY series installment, collectively titled MOUSE, is divided up as follows: MOUSE (INTRO) | PRE-MICKEY MICE (1904–1913) | PRE-MICKEY MICE (1914–1923) | PRE-& POST-MICKEY MICE (1924–1933) | POST-MICKEY MICE (1934–1943) | POST-MICKEY MICE (1944–1953) | POST-MICKEY MICE (1954–1963) | POST-MICKEY MICE (1964–1973) | POST-MICKEY MICE (1974–1983) | POST-MICKEY MICE (1984–1993) | POST-MICKEY MICE (1994–2003).

(1924–1933)

According to HILOBROW’s periodization scheme, the cultural era known as the nineteen-twenties begins c. 1924 and ends c. 1933. During this period, let’s see how the mice tropes — surfaced via this audit, and dimensionalized in the series’ introduction — shake out via pop culture.

PS: It will be interesting to see what sort of influence Mickey has on his fellow pop-culture mice after he first appears in 1928. For one thing, how many pop-culture mice with alliterative names will now begin to appear?

PRE-MICKEY…

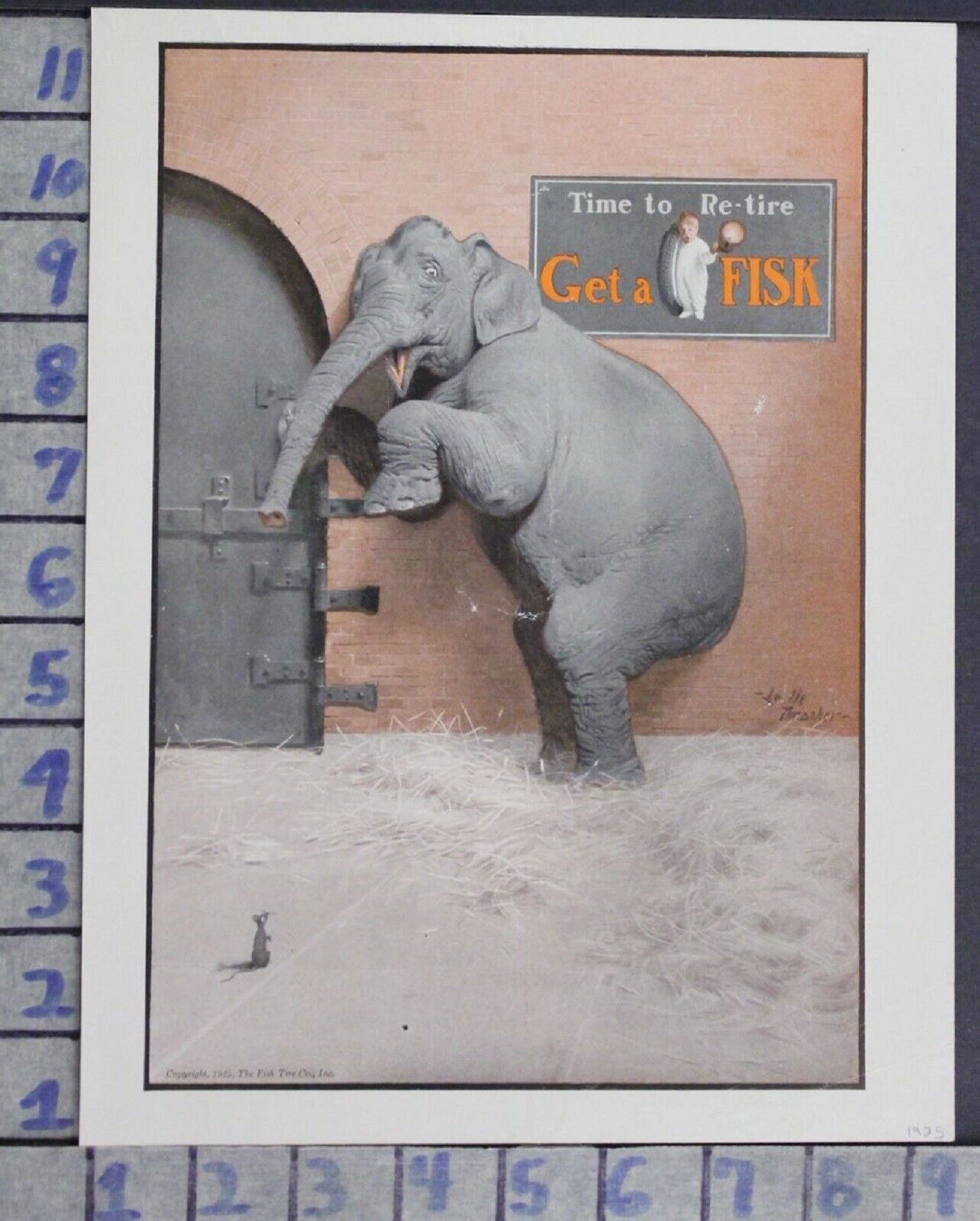

In this 1925 ad for Fisk Tire, we find the old elephant-frightened-of-a-mouse gag.

In 1924, the Bureau of Biological Survey (later the Fish and Wildlife Service) began eliminating all predators from Kern County, Calif. — hunting coyotes and hawks, in order to protect livestock. Drought had dried up the large Buena Vista Lake, and farmers began planting maize and barley in the fertile lake bed. Mice, no longer hunted by predators, were attracted to this bumper crop. In 1926, however, the drought ended and the lakebed filled up again — driving the now-enormous mouse population into the oil boom settlements of the Honolulu Hills. An estimated 30 to 100 million mice (!) squeezed into every available space, halting all oil production and forcing the oil workers to spend their time killing mice.

Stories appeared of mice chewing hair, running across the desks of schoolchildren, and even killing and devouring an entire sheep. Large mechanical harvesters were used to kill mice until the blades were choked with blood and fur. The City of Taft was defended by long rows of trenches filled with strychnine-laced straw. Nothing helped until the new lake began attracting thousands of birds of prey to the area; at the same time, a bacillus outbreak hit the dense mice population, killing millions.

The diorama above is from the West Kern Oil Museum.

POST-MICKEY…

Life Magazine – May 8, 1931 — Mouse in Golf Bag

Movie Crazy (1932) has a long comic sequence in which Harold Lloyd accidentally puts on a magician’s coat while at a fancy nightclub. The sequence ends when Harold accidentally opens a box of mice concealed within the coat, causing mass panic among the women on the dance floor.

Billy Barty, an actor who stood 3 ft 9 in, due to cartilage–hair hypoplasia dwarfism, playing a mischievous mouse in Footlight Parade (1933).

PRE-MICKEY…

There’s a mouse in the (racist) 1924 Felix the Cat cartoon Felix Goes Hungry who not only escapes Felix again and again but taunts and mocks him, and steals his hard-earned cash.

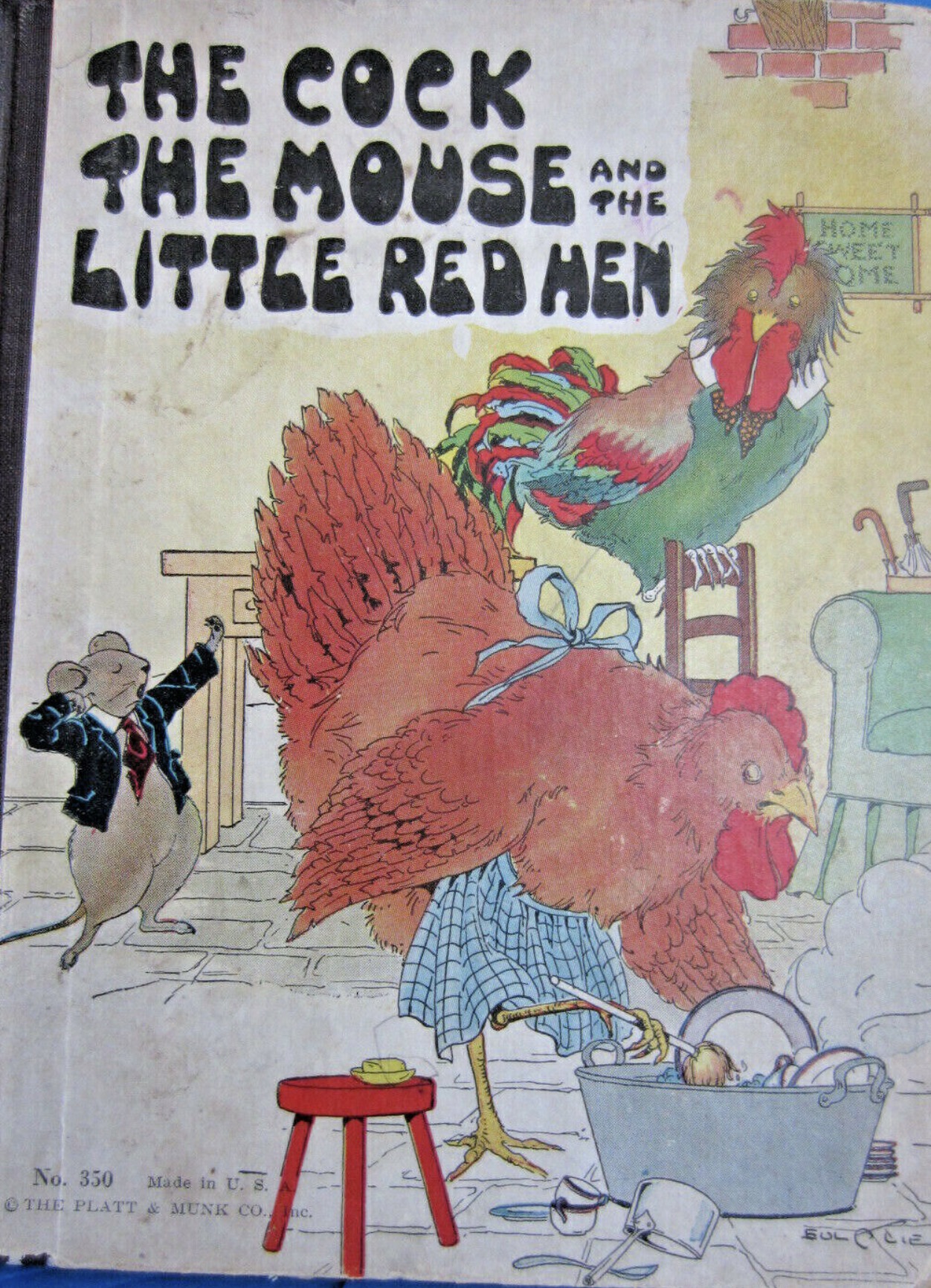

We’ve met this mouse in previous installments. A lazy fellow who won’t help the Little Red Hen do any household chores. This 1925 edition is illustrated by Eulalie (Eulalie Minfred Banks, who illustrated many classic children’s books including nursery rhymes, fairy tales and folk stories).

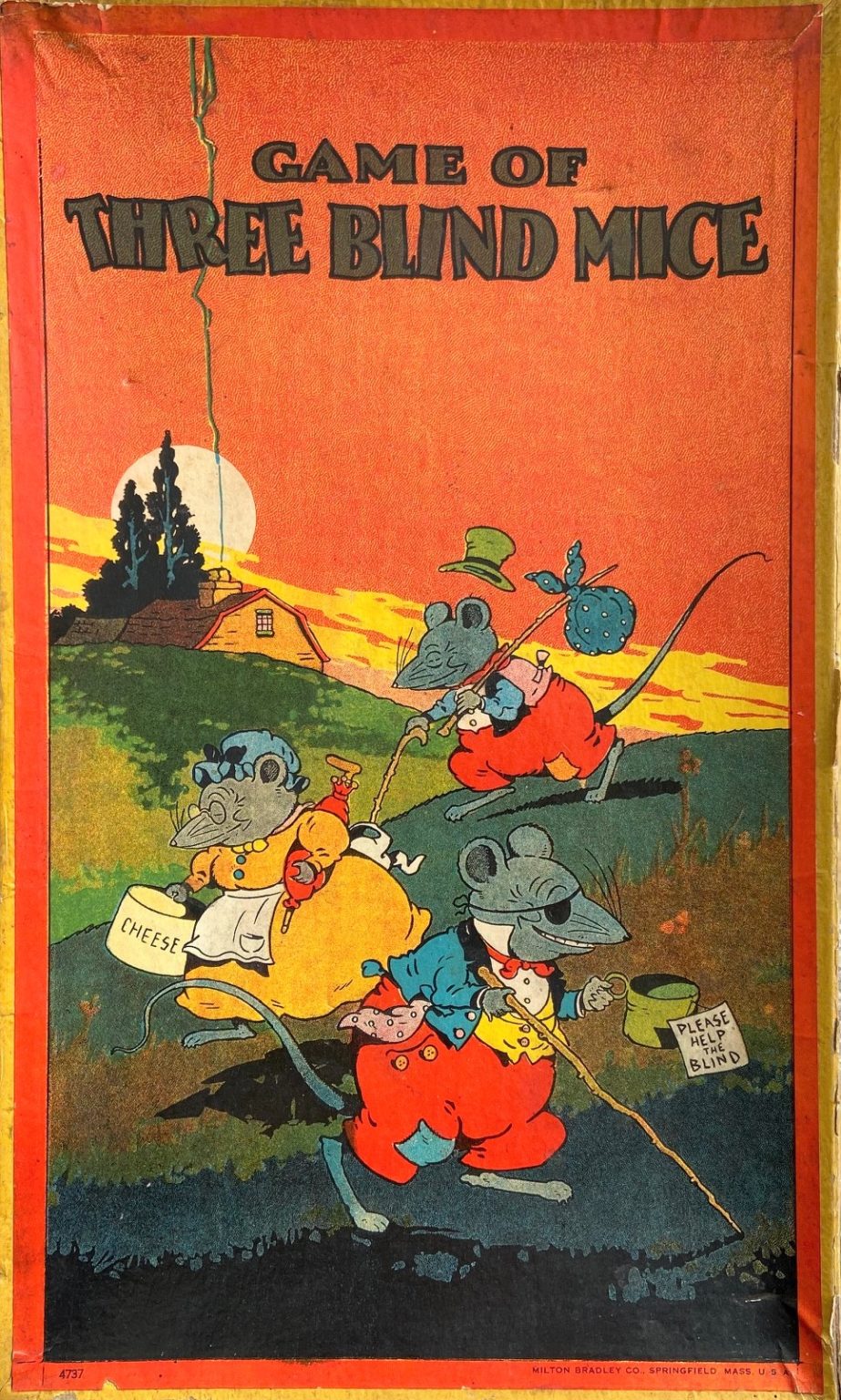

The three blind mice depicted on this 1925 Milton Bradley boardgame look like grifters and con artists, don’t they?

In this c. 1925 image by cartoonist and illustrator Charles J. Coll, a rapscallion mouse prods a bear’s toothache.

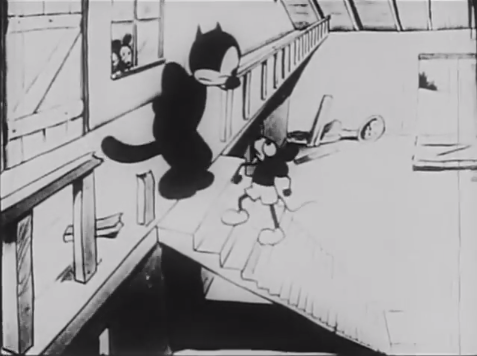

Alice’s Mysterious Mystery is a 1926 short film by the Walt Disney Studio and Winkler Pictures. It is part of the Alice Comedies. Where are the missing puppies going to? That’s the question before detectives Alice and Julius. But as usual, Pete the criminal mastermind bear is behind the kidnappings. Pete’s henchman is a mouse. They’re selling the dogs to a sausage factory…

In Felix the Cat Misses His Swiss (1926), Felix The Cat gets a job protecting a cheese shop from three industrious mice. When he foils their plans, they head off for Switzerland in search of bigger and better cheeses — but Felix is in pursuit. The version at the link here was colorized later.

In “The Mouse’s Bride“, a 1928 Aesop’s Fables animated short, a determined mouse helps to free his beloved from her oppressive master. This is where Tarantino got the idea for Django from.

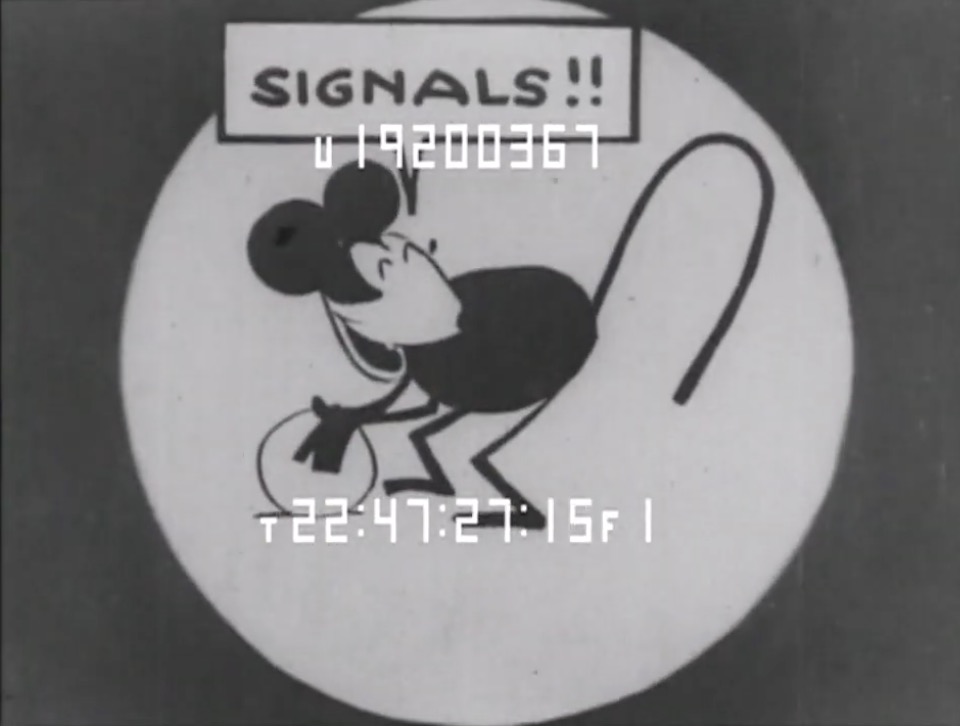

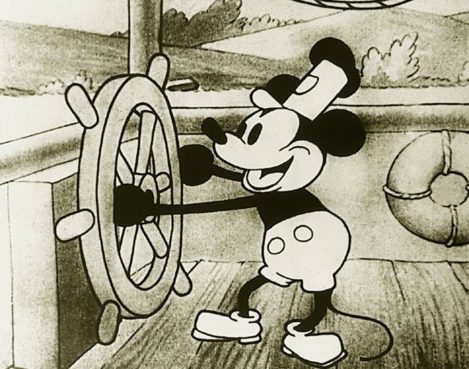

Walt Disney’s animated Mickey Mouse character debuted publicly in the short film Steamboat Willie (1928). Mickey is piloting a steamboat when Captain Pete comes to the bridge and throws him off. They stop to pick up cargo. Minnie just misses the boat and Mickey uses the crane to grab her. With help from Mickey, Minnie cranks the goat’s tail, and it plays “Turkey in the Straw.”

Mickey accompanies on percussion and by torturing various animals, until Pete comes down and puts a stop to it, putting Mickey to work peeling potatoes.

The Nov. 5, 2019 episode (“‘Zip-a-Dee-Doo-Dah,’ Minstrels in Hollywood and The Oscars”) of Karina Longworth’s podcast “You Must Remember This” helps us get more granular. In Longworth’s discussion of Steamboat Willie and other early MM cartoons, she notes that Mickey and his friends were associated with minstrelsy thanks to “their big bug eyes and their white gloves, which were often worn in minstrel shows by dandy characters, as a signifier that they aspired to a higher class.” She also notes the use of “Turkey in the Straw” in Steamboat Willie — a song which had since “Zip Coon” become closely associated with minstrelsy. “So from the beginning, Disney sought to take up the tropes of this other form of popular culture.”

Fun fact: Steamboat Willie won audiences over because it was scored in such a way that the music punctuated the physical motions occurring. Though the practice of synchronizing actions to the rhythm of the music dates back to the days of silent film, within the world of animation this practice henceforth became known as “Mickey Mousing.”

Steamboat Willie was followed that same year by Plane Crazy, The Gallopin’ Gaucho, and The Barn Dance.

MM 1929: The Opry House, When the Cat’s Away, The Barnyard Battle, The Plowboy, The Karnival Kid, Mickey’s Follies, Mickey’s Choo-Choo, The Jazz Fool, Jungle Rhythm, The Haunted House, Wild Waves.

MM 1930: Fiddling Around (AKA Just Mickey), The Barnyard Concert, The Cactus Kid, The Fire Fighters, The Shindig, The Chain Gang, The Gorilla Mystery, The Picnic, Pioneer Days.

Originally introduced by Louis Marx Toys in 1931 is the MARX MERRY MAKERS Mouse Band. The most highly successful windup tin toy that Marx ever manufactured.

MM 1931: The Birthday Party, Traffic Troubles, The Castaway, The Moose Hunt, The Delivery Boy, Mickey Steps Out, Blue Rhythm, Fishin’ Around, The Barnyard Broadcast, The Beach Party, Mickey Cuts Up, Mickey’s Orphans.

MM 1932: The Duck Hunt, The Grocery Boy, The Mad Dog, Barnyard Olympics, Mickey’s Revue, Musical Farmer, Mickey in Arabia, Mickey’s Nightmare, Trader Mickey, The Whoopee Party, Touchdown Mickey, The Wayward Canary, The Klondike Kid, Mickey’s Good Deed.

MM 1933: Building a Building, The Mad Doctor, Mickey’s Pal Pluto, Mickey’s Mellerdrammer, Ye Olden Days, The Mail Pilot, Mickey’s Mechanical, ManMickey’s Gala Premier, Puppy Love, The Steeple Chase, The Pet Store, Giantland.

“There’s a certain animile, making everybody smile. What’s this fellow’s name? Mickey! Mickey! Tricky Mickey Mouse!” — 1930 song by Harry Miles

From 1928 through c. 1933, which is to say through what I’d call the second half of the cultural era known as the Twenties (1924–1933), Mickey Mouse was a rogue, a prankster, sometimes even a jerk. As noted in this series’ first installment, MM’s persona is indebted to that of minstrelsy’s roguish, work-averse, libidinal “coon” character. In Mickey’s earliest cartoons, he is 100% concerned with “getting over” — that is to say, doing just enough work to keep from being fired. In his earliest appearances, Mickey drinks beer, smokes, lusts after Minnie Mouse, and lives by his wits. He is petty and vengeful, looking for ways to one-up anyone who annoys him.

However, within just a couple of years, Walt would begin a whitewash campaign to make us forget the original Mickey. How? He began to spread the story that Mickey’s personality was modeled more or less entirely after Charlie Chaplin’s Little Tramp character.

A 1931 piece by Harry Carr quotes Disney saying, “We wanted something appealing, and we thought of a tiny bit of a mouse that would have something of the wistfulness of Chaplin… a little fellow trying to do the best he could.” Ever since, Mickey has been described as “a graphic analogue to Charlie Chaplin’s Little Tramp, trying to get by (and have a little fun) in a not-always-friendly world,” to quote Garry Apgar’s Introduction to A Mickey Mouse Reader. Yes, there’s something to the Chaplin-Mickey comparison, but let’s dig into this a bit. It’s not nearly so simple as that.

Alva Johnston, writing in 1934, noted that although Chaplin and Mickey may “have the same blend of hero and coward, nit-wit and genius, mug and gentleman,” Mickey lacks “the emotional subtleties of Chaplin, his repose, wistfulness and pathos.” This is a key insight: Mickey was not, at least at first, a sentimental figure. We learn nothing from Mickey, he isn’t inspiring. Writing in 1934, the highbrow novelist E.M. Forster indicates that this is exactly why he likes Mickey Mouse, as opposed to middlebrow cinema: “Here [in the movie theater] art is not, life is not. Not happy, not unhappy, I sit in an up-to-date stupor, while the international effort unrolls.” Mickey, however, is “energetic without being elevating. No one has ever been softened after seeing Mickey or has wanted to give away an extra glass of water to the poor. He is never sentimental, indeed there is a scandalous element in him which I find most restful.”

Scandalous: Mickey was shocking, outrageous to settled norms. The same could not be said of Chaplin’s Little Tramp.

Mickey Mouse was also outrageous to settled forms. An antic hodgepodge of rubbery limbs and round body parts, at the level of form the Mickey character is incommensurable. He isn’t fungible. Literally and figuratively, Mickey is a round peg that won’t fit into a square hole. Like Silly Putty, a Super Ball, a Slinky, a Crazy Straw, Mickey’s form is not useful or educational; it is weird, funny, eccentric, scandalous.

America, in the early 20th century, was the source of Fordism — the mass production of standardized goods on a moving assembly line. Mickey is an anti-Fordist homonculus. He serves as a rebuke to standardization, to efficiency. Note that Chaplin wouldn’t be sucked into factory equipment, in Modern Times, until 1936.

When C.A. Lejeune, the first female British film critic, admiringly wrote, in 1929, that “the whole cunning of Mickey lies in its deliberate sub-tones — it is a whispered and wicked commentary on Western civilization,” she was voicing the highbrow’s (anti-middlebrow) appreciation for the comic, carnivalesque lowbrow. Gilbert Seldes, writing in The New Yorker, in 1931, describes MM as a trickster figure: “In the current American mythology, Mickey Mouse is the imp….”

The credit for early Mickey’s impish physicality must go to Ub Iwerks, who first drew and animated Mickey. One of his colleagues noted that Iwerks’s cartoons “swing” — his syncopation, his gift for extending rhythmic lines, distinguished Iwerks’s animations from all the rest.

John Canemaker, writing in the New York Times in 1995, described MM’s original look like so: “A white mask on a black circular head with pie-shaped eyes, two smaller ear-circles and two-button short pants on a round black body. But Mickey was also a grungy, goggle-eyed, long-snouted ratlike creature, with tubular arms and legs, no gloves, no shoes and no class.”

Edwaard Lewine, writing in the same newspaper in 1997: “He was scrawny, with a long, sinister face. His hands and feet knew neither glove nor shoe and he spoke in funny noises, not words. And he was a mean guy.”

Maurice Sendak, on MM: “He was a malignant little creature in the beginning, which is why he was so charming.” In a 2004 New York Times interview, Sendak would elaborate: “His character was the kind I wished I’d had as a child: brave and sassy and nasty and crooked and thinking of ways to outdo people.”

The French famously love American figures — Edgar Allan Poe, Josephine Baker, Sidney Bechet, Jerry Lewis, Philip K. Dick — whose work rebukes, at the level of form, remorseless American-style efficiency. They were early adopters of Mickey Mouse. A 1929 article in the Parisian monthly Jazz: l’actualité intellectuelle exults, “Never have pictures achieved greater, more varied effects, never has freer rein been given to lively antics and subtle humor.” In a more philosophical vein, the article asks: “Where are we, if not somewhere in the uninhibited world of dreams, in the lawless realm of inanimate objects?”

“Society’s most natural ally in maintaining law and order, conformity, and the institutions that relegate freedom to a perpetual utopia,” claimed Herbert Marcuse at midcentury, is resignation to the subjective tyranny of time and space. Mickey Mouse knows no such resignation. A 1930 article by Creighton Peet titled “Miraculous Mickey” exults that MM cartoons “are ‘free’ in the fullest and most intelligent sense of the term. They know neither space, time, substance nor the dignity of the laws of physics.” Writing in the New York Times in 1935, L.H. Robbins said of Mickey: “He suspends the rules of common sense and correct deportment and all the other carping, conventional laws, including the law of gravity, that hold us down and circumscribe and cramp our style.” And Graham Greene, writing in 1935 about Fred Astaire, noted that with his “quick physical wit, his incredible agility,” Astaire — who might almost be a character created by Disney — “belongs to a fantasy world almost as free of Mickey’s from the law of gravity.”

Mickey’s rubbery form made him an emblem of a free-wheeling, fast-thinking, adaptable mode of living — which, during the Depression — must have been extremely attractive.

For all this talk of scandal, impishness, wickedness, though, Mickey was an innocent figure — a childish grownup, one who may smoke and drink but who has somehow avoided becoming resigned to the way-things-just-are. Neither man nor mouse, child nor adult, Mickey is fascinatingly feral. “Childhood is cannibals and psychotics vomiting in your mouth!” Maurice Sendak — an exact contemporary, and fan, of Mickey’s once said in an interview with Art Spiegelman. What Sendak means is that childhood is feral; it’s innocent and wicked, sweet and scandalous. Like Mickey.

POST-MICKEY…

I haven’t read Meddlesome Mouse, but the title suggests that it belongs in this trope. Neville was an illustrator — best known for the popular Betsy-Tacy series — and author of this 1931 book.

Max Fleischer cheekily inserts MM into the 1933 Betty Boop short Betty Boop in Snow-White. It’s as though MM had tunneled into the film from his own franchise — a scamp-like thing to do.

PRE-MICKEY…

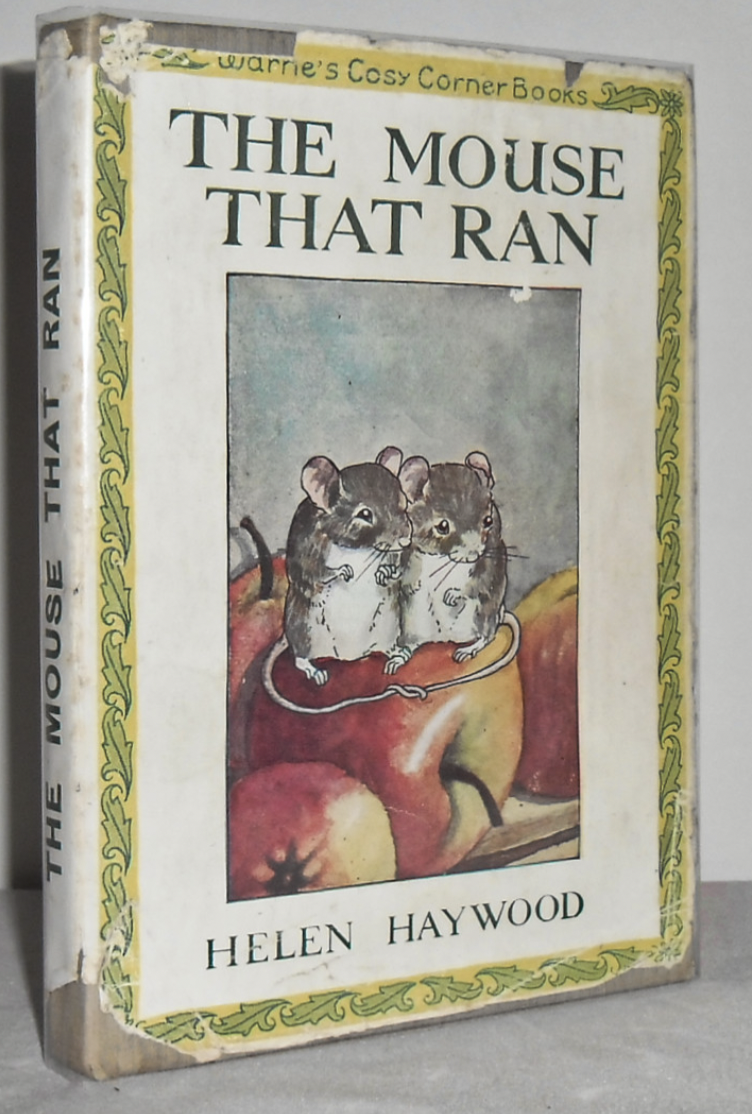

Helen Haywood published her first illustrated children’s book — in a small Beatrix Potter-style format — at age 19, in 1926. A story of a little grey mouse who runs around meeting other animals, and finds a female mouse to marry.

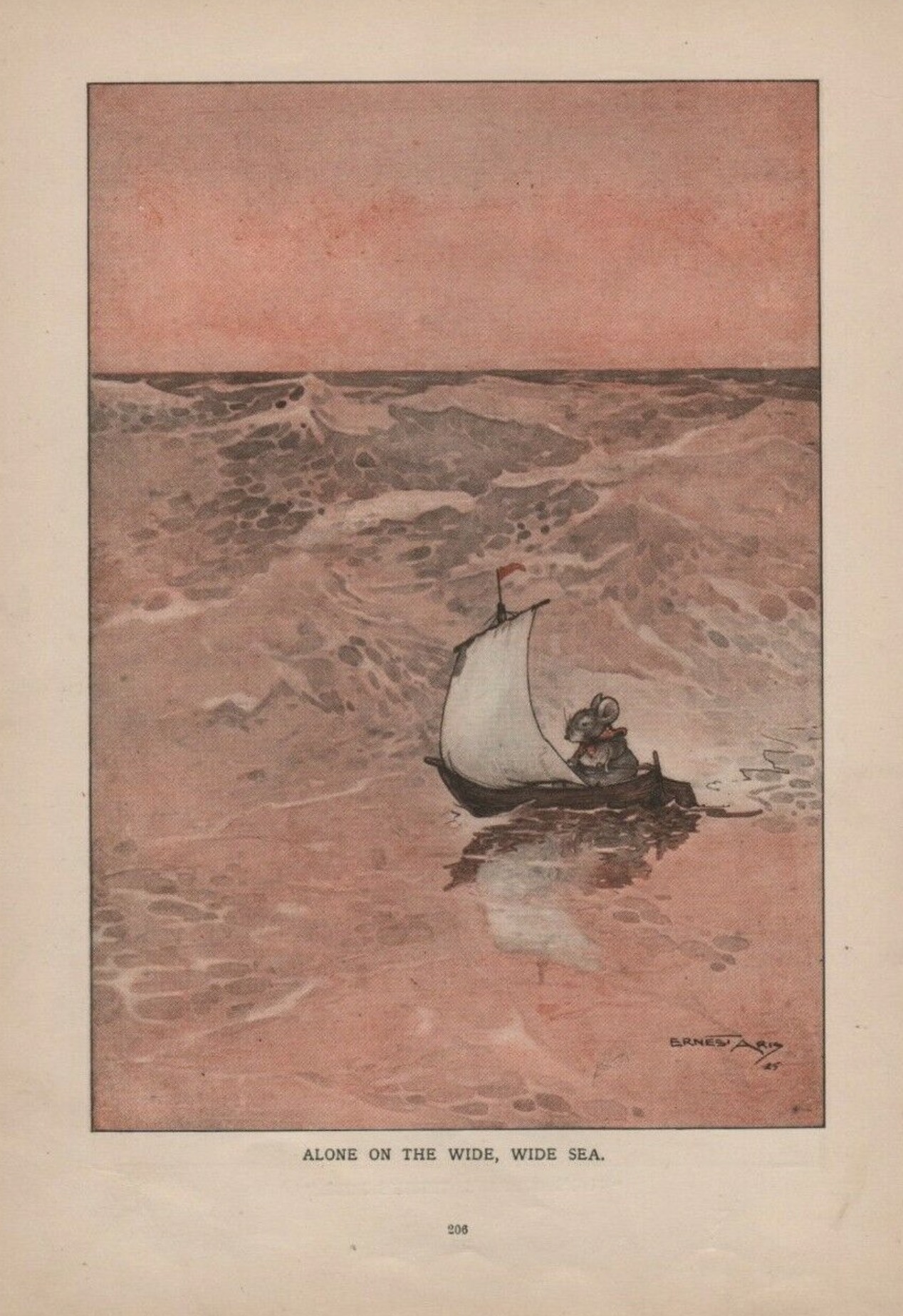

An Ernest Aris illustration — “Alone on the wide, wide sea.” — from a 1928 book called The Wonder Book of Pictures and Stories for Boys and Girls.

POST-MICKEY…

Fritz Lang’s 1929 sci-fi film Woman in the Moon (Die Frau im Mond) incidentally sends a cute mouse to the moon.

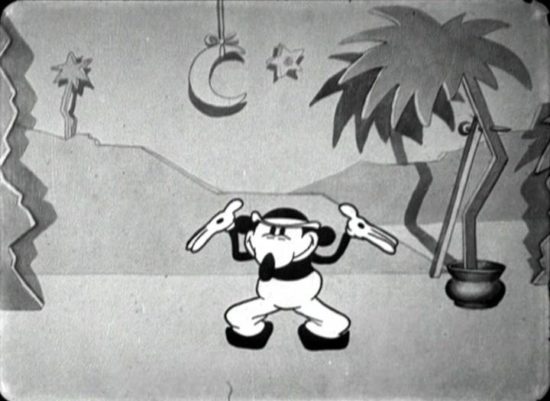

Other directors continue to make animated mouse shorts. Paul Terry’s “A Lad and His Lamp” (1929), for example, is about an intrepid adventurer mouse.

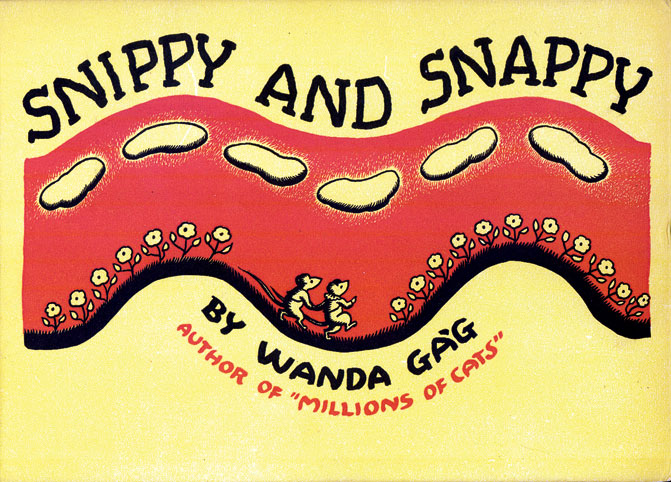

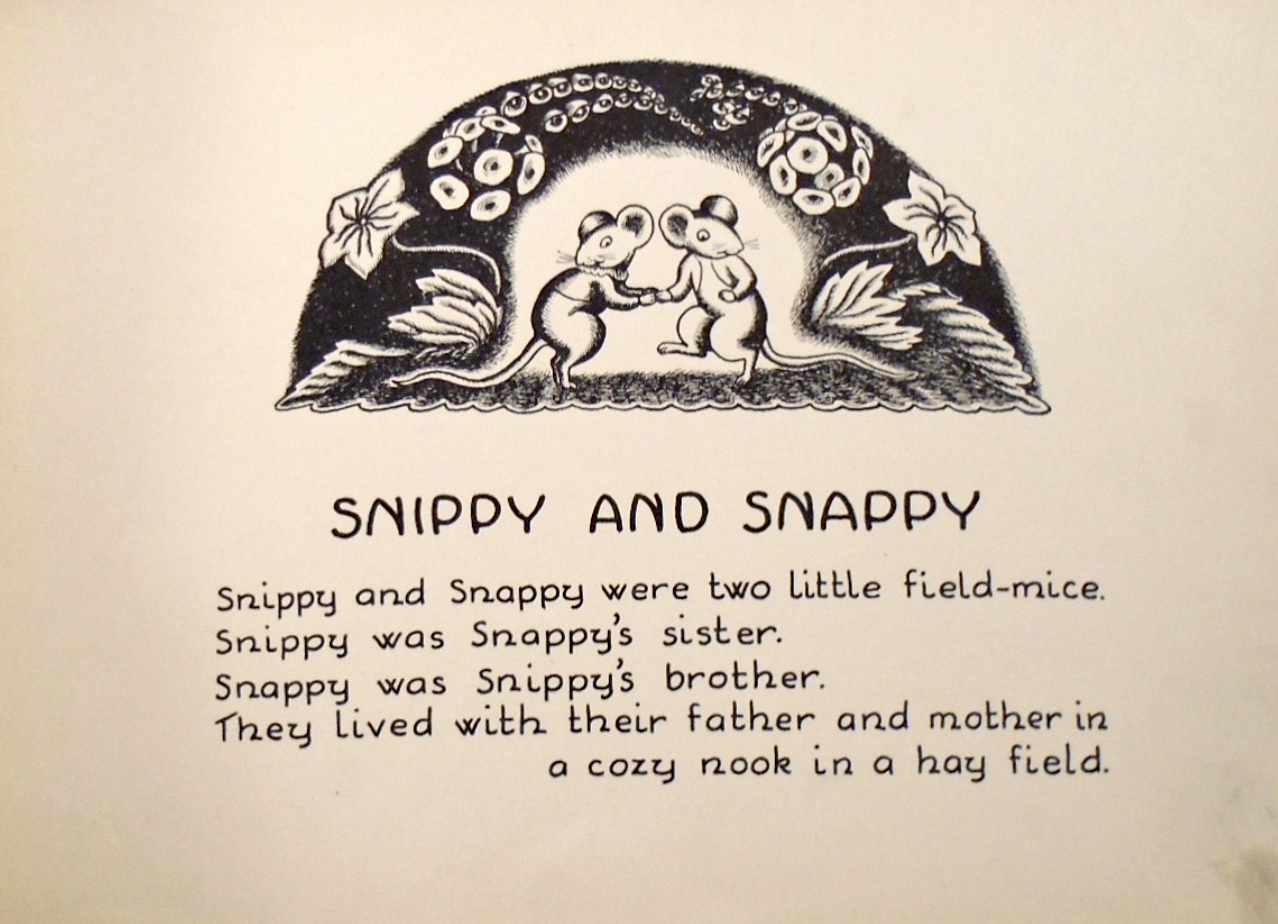

In Snippy and Snappy (1931), Wanda Gág introduces us to brother and sister field mice living in a cozy nook in a hay field. One day Snippy and Snappy wander away from home. Their journey takes them to a house full of mysterious things. Gág’s delightfully detailed illustrations capture the wonder and playfulness of their adventures.

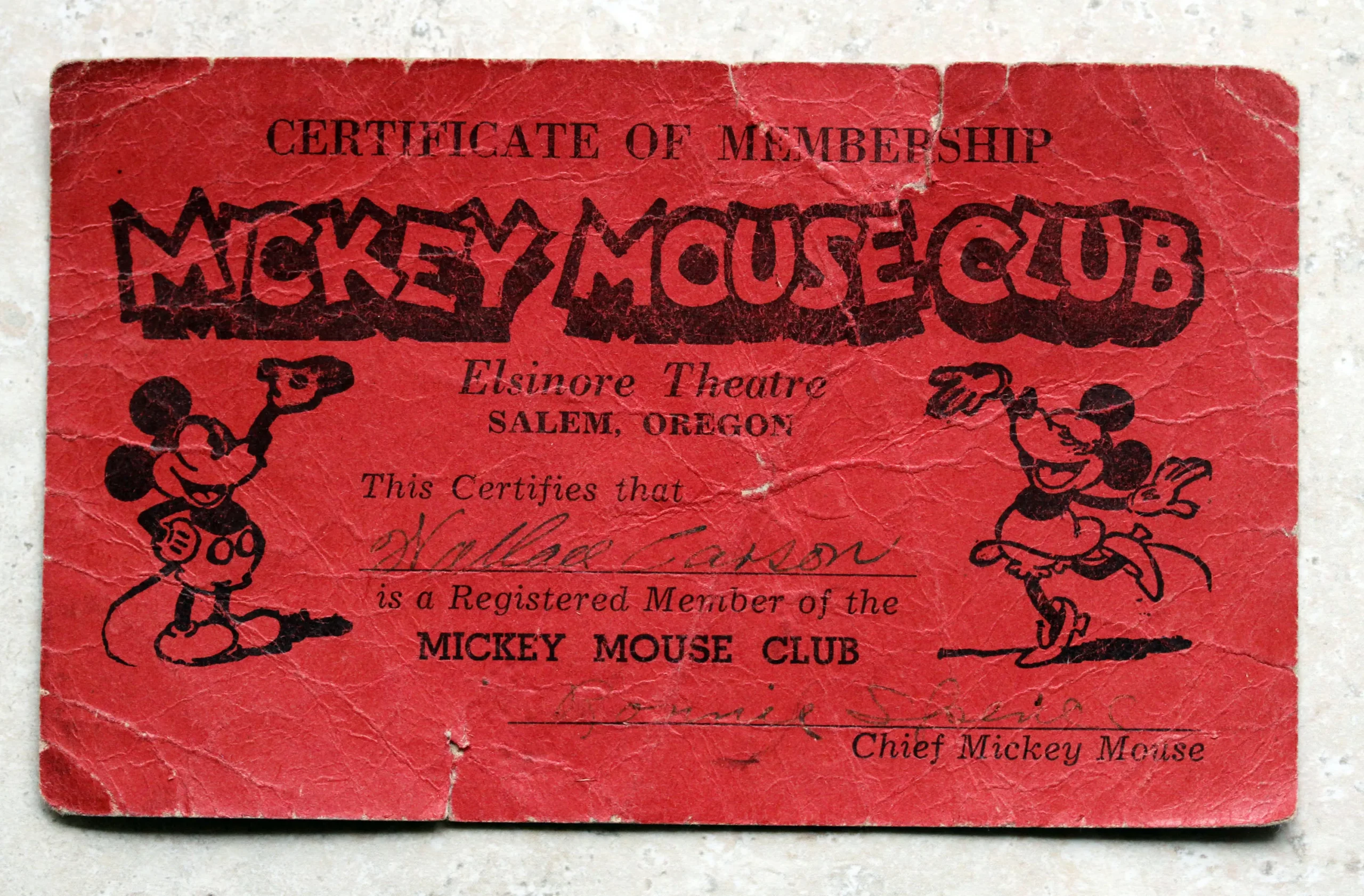

By the end of 1931, some three quarters of a million children were enrolled in Mickey Mouse clubs. They attended MM performances at movie theaters, sang a theme song, and recited a creed: “I will be a square-shooter in my home, in school, on the playground, wherever I may be. I will be truthful and honorable and strive always to make myself a better and more useful little citizen.… in short, I will be a good American.”

That’s right, Mickey — the libidinous, scandalous, impish trickster — had become a role model for children. Under Mickey’s aegis, American kids were encouraged to be useful, hard-working, and well-behaved. “Mickey… had become virtually a national symbol, and as such he was expected to behave properly at all times,” recounts Stephen Jay Gould. “If he occasionally stepped out of line, any number of letters would arrive at the Studio from citizens and organizations who felt that the nation’s moral well-being was in their hands. … Eventually he would be pressured into the role of straight man.”

In the terms of this series’ analysis, we’d say that Mickey dropped the REBELLIOUS SCAMP trope while doubling down on the INTREPID ADVENTURER and SCRAPPY SURVIVOR tropes.

Disney story artists began to write Mickey’s roles differently. Alva Johnston, in 1934, took note of the change, which Walt openly discussed with reporters: “Extreme vigilance is exercised to keep [Mickey Mouse] from becoming a smart Alec. Too much whimsy and fantasy are objectionable.”

In his 2006 biography of Walt Disney, Neal Gabler hails “Mickey’s intrepid optimism, his pluck, his naivete that often got him into trouble and his determination that usually got him out of it.” Right — this is the Boy Scout that Mickey became.

In 1933, journalist Edwin C. Hill, writing in the Boston Evening American, hailed Mickey as a “gay, gallant and resourceful little creature” — one who showed up “at the time the country needed him most — at the beginning of the depression.” (Hill is proleptically writing about Shirley Temple, here — who wouldn’t achieve fame until Bright Eyes, a 1934 feature film designed specifically for her talents.) But you get the idea: Mickey the trickster, Mickey the Zip Coon manqué, was being repurposed as an uplifting figure.

No longer an emblem of wit vs. shit, MM was being refashioned to represent the virtues of cheerful optimism, a can-do attitude. He became even more beloved, as a result — though the process of sanding down Mickey’s edges until he was entirely insipid had begun.

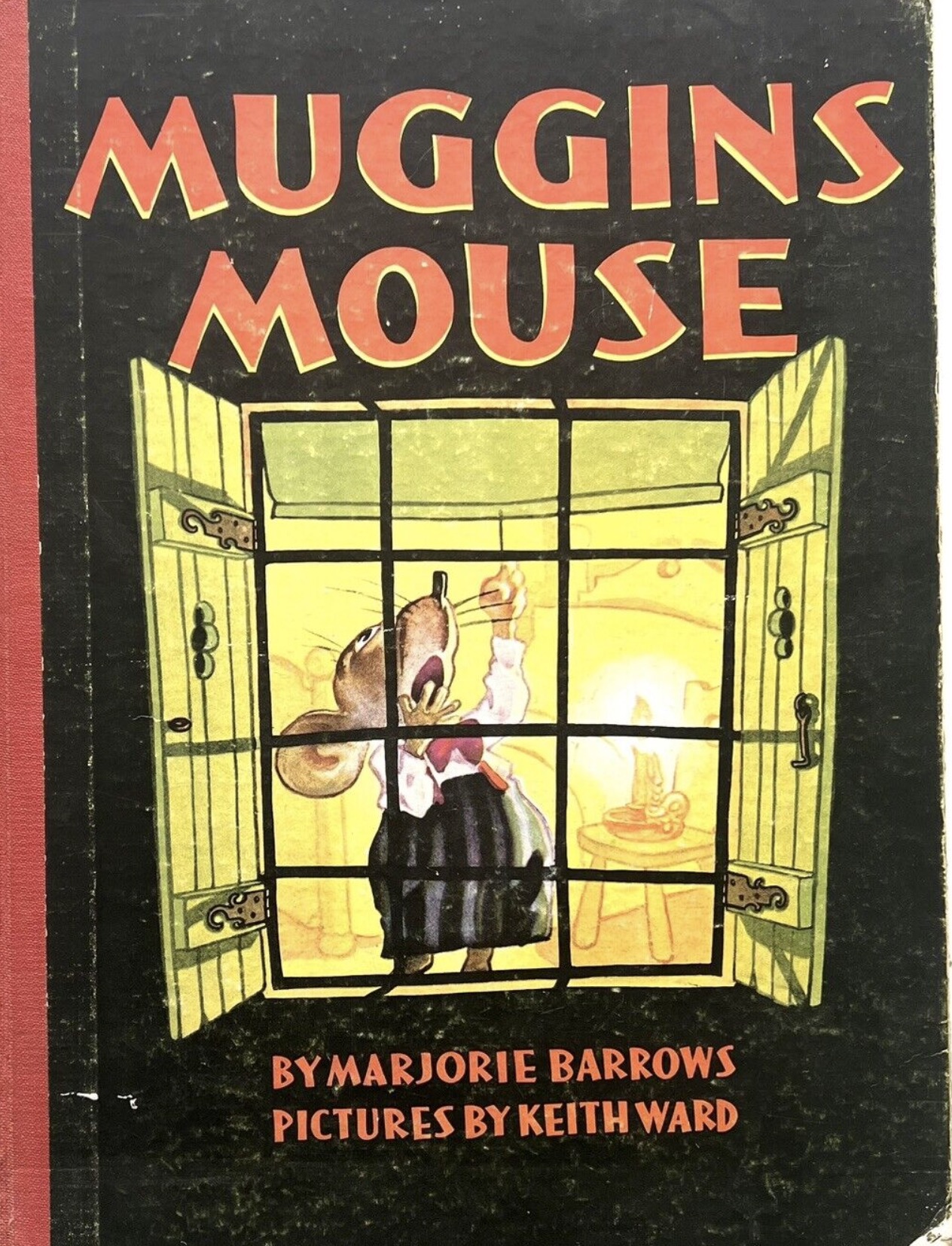

Muggins Mouse is a 1932 collection of stories. Illustrated by Keith Ward and written by Marjorie Barrows.

PRE-MICKEY…

In the 1927 animated short Eye Jinks, Felix the Cat hires out to an optometrist as a mouse catcher. After driving away the offending mice, Felix decides to catch a nap. The mice return and, finding Felix asleep, slip a pair of large, powerful glasses over his eyes… causing Felix to have wild hallucinations.

Lehmann “Nina” Cat and Mouse EPL 790, from 1927. Lithographed tin clockwork toy.

I haven’t read Mercy and the Mouse, a 1928 story collection. It’s humorous stories about Mercy, an ambitious cat. Peggy Bacon (1895–1987) was cool. In 1919, at the age of 24, she wrote and illustrated her first book, The True Philosopher and Other Cat Tales. She went on to illustrate over 60 books, 19 of which she also wrote, including a successful mystery book, The Inward Eye, which was nominated for an Edgar Allan Poe award in 1952 for best novel. Bacon’s popular drawings appeared in magazines such as The New Yorker, New Republic, Fortune, and Vanity Fair.

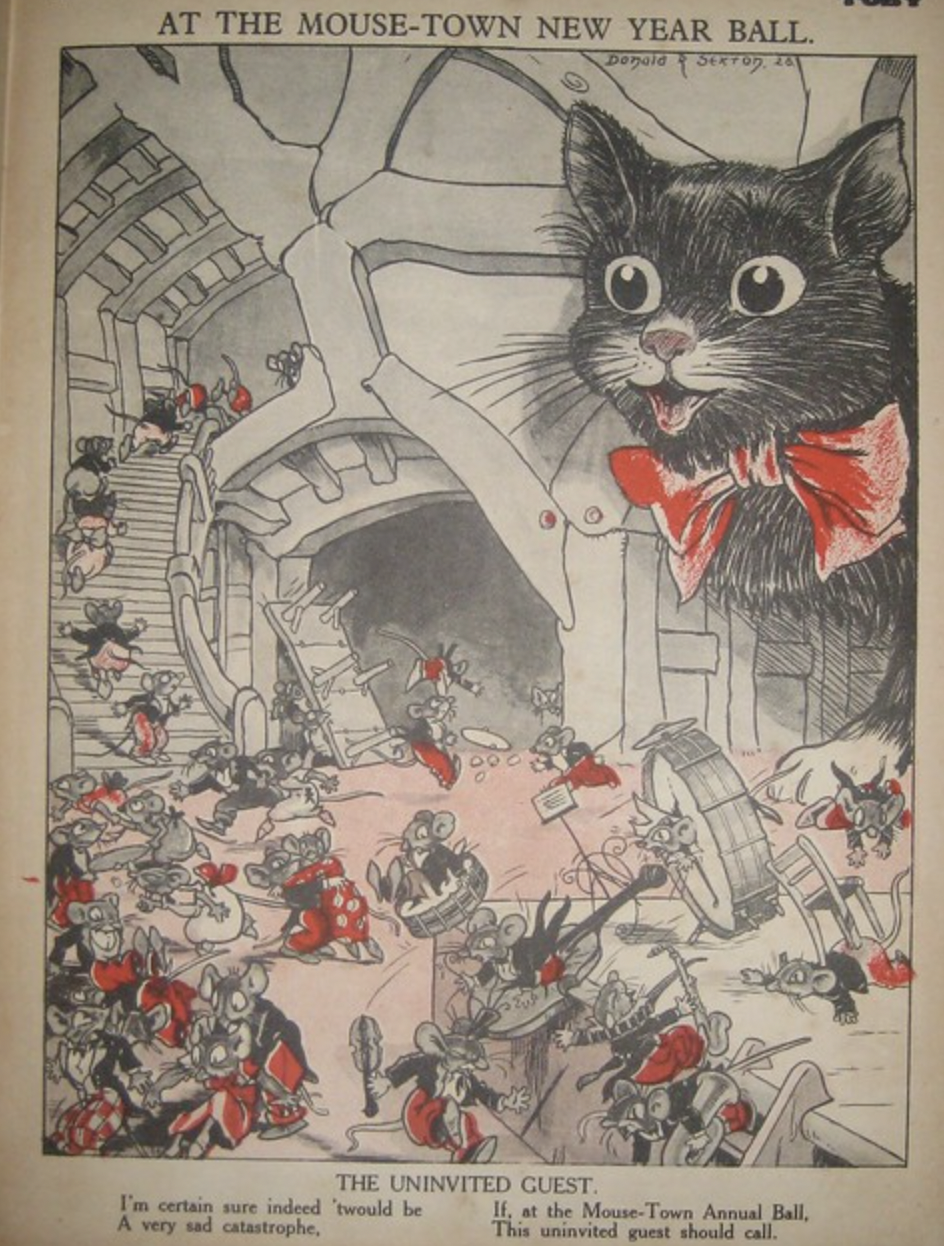

“The Mouse-Town New Year Ball” from The Toby Book (1928).

POST-MICKEY…

1929 Paul Terry Land o’ Cotton

Mice sold into slavery and driven to pick cotton by whip-cracking cats plot their escape to freedom. dealing so explicitly with American slavery, including a slave auction scene with the mice being enslaved and the cats being the slavers.

Here’s what one viewer has to say: “Many may argue that this cartoon is racist since it depicts slavery in a lighthearted manner, but I beg to differ. Aside from a watermelon gag, it doesn’t seem like the slaves, portrayed as mice, are being lampooned. Instead, one is portrayed as a hero as he and his female companion escape. To be honest, every time I watch this cartoon, I’m rooting for the mice and cheer when the donkey kills their owner.”

Milton Mouse confronts the cat, from A Close Call, a 1929 cartoon. Van Beuren’s Aesop’s Fables.

The film, like other Aesop Sound Fables at that time, featured Milton and Rita as the main characters.

Writing in 1931, in a private journal entry, the German Jewish intellectual Walter Benjamin muses, “In these [Mickey Mouse] films, mankind makes preparations to survive civilization. Mickey Mouse proves that a creature can still survive even when it has thrown off all resemblance to a human being. He disrupts the entire hierarchy of creatures that is supposed to culminate in mankind. … So the explanation for the huge popularity of these films is not mechanization, their form; nor is it a misunderstanding. It is simply the fact that the public recognizes its own life in them.”

The Western social order, Benjamin seems to suggest, was already becoming inhuman in 1931. Round pegs — and the melancholy, sentimental, hapless Benjamin was the roundest of pegs — were increasingly being forced into square holes. The equivocal good news? Humankind could adapt — at best, into Mickey Mouse-like creatures, not entirely human but not entirely inhuman. Rubbery, resilient, irrepressible, this mutated version of humankind would survive and thrive. Wit would continue to outmaneuver shit.

In his 1941 seminal work of political psychology Escape from Freedom, Erich Fromm — like Benjamin, a member of the Frankfurt School; Fromm fled Germany after the Nazi takeover — would also suggest that MM’s fan-base is drawn by recognizing “something that is very close to its own emotional life,” that is to say, a small creature overwhelmed by a large society. “The spectator lives through all his own fears and feelings of smallness and at the end gets the comforting feeling that, in spite of all, he will be saved and will conquer the strong one” — i.e., thanks to fortuitous accidents that allow him to escape his fate, as opposed to creating his own escape.

These anti-fascist readings of Mickey Mouse are half-hearted, to be sure. Mickey represents the little guy who may not be able to make much of a difference… but he’s got grit. He’s a cheerful version of the character Peter Lorre would play after the diminutive Jewish actor fled the rise of Nazism in the Thirties: Unable to stop thugs from pushing him around, but outraged and resilient every time it happens.

I believe that this is the sort of thing that film writer — and former Chaplin comedy producer — Terry Ramsaye was getting at, in 1932, when he opined that Mickey is “all things to all men. He is a gust of thoughtless fun to the casual, the lowbrow, the thoughtless. He is the voice and personification of the weltschmerz to the sophisticate and a blood brother to the philosopher.”

In Rudolf Ising’s 1932 Warner Bros. Merrie Melodies animated short “It’s Got Me Again!”, a mouse ventures out of his hole. His tail gets caught in a mousetrap, but he escapes unharmed. He waves forth the other mice. Out they come, all ready to play music and have fun. A hungry cat breaks in and tries to catch a mouse. But he’ll have to deal with the entire mouse community, and their resourceful use of musical instruments as weapons, before he’ll get one.

This is the first Warner Bros. cartoon to be nominated for an Academy Award. It lost to Walt Disney’s Flowers and Trees (1932).

PRE-MICKEY…

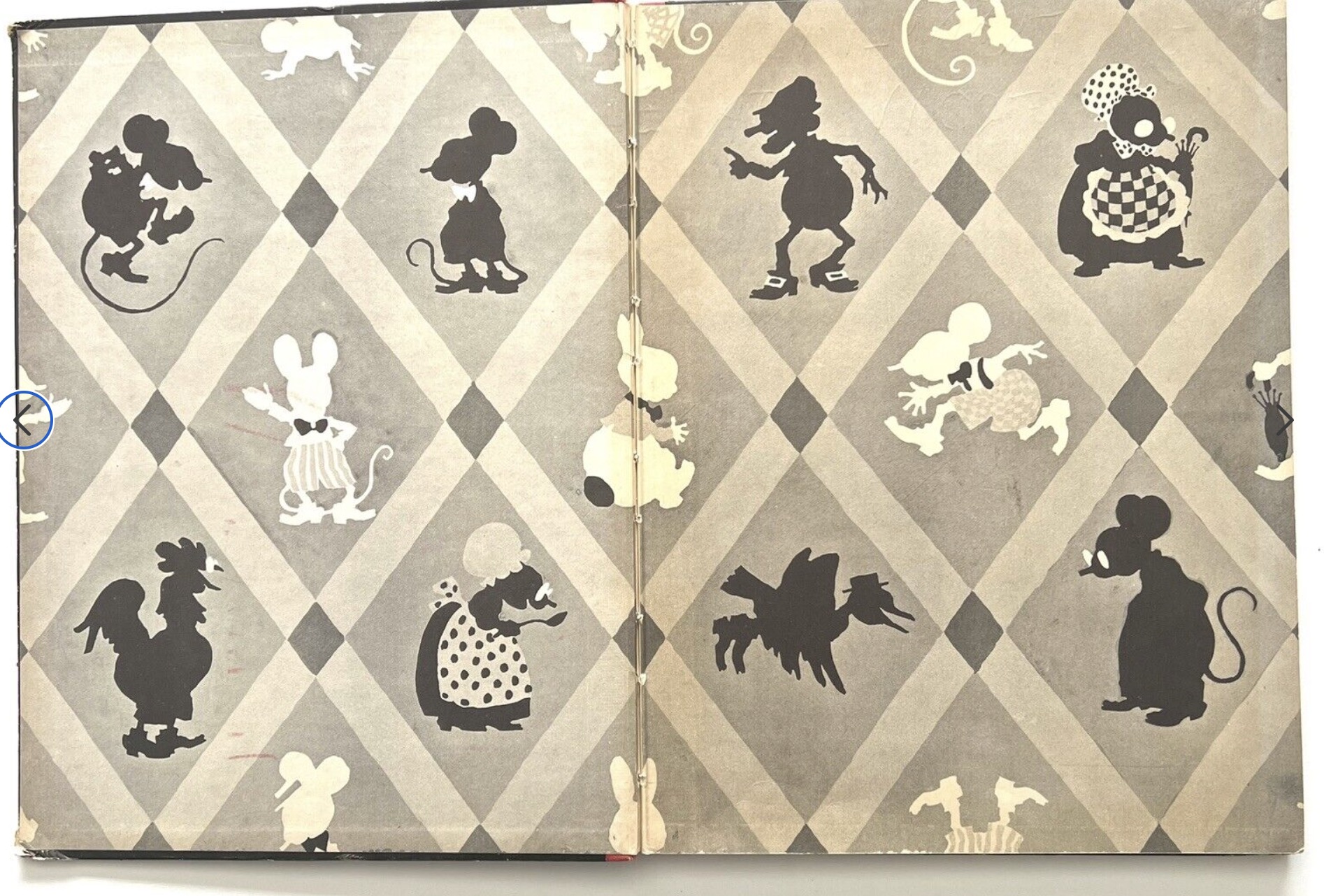

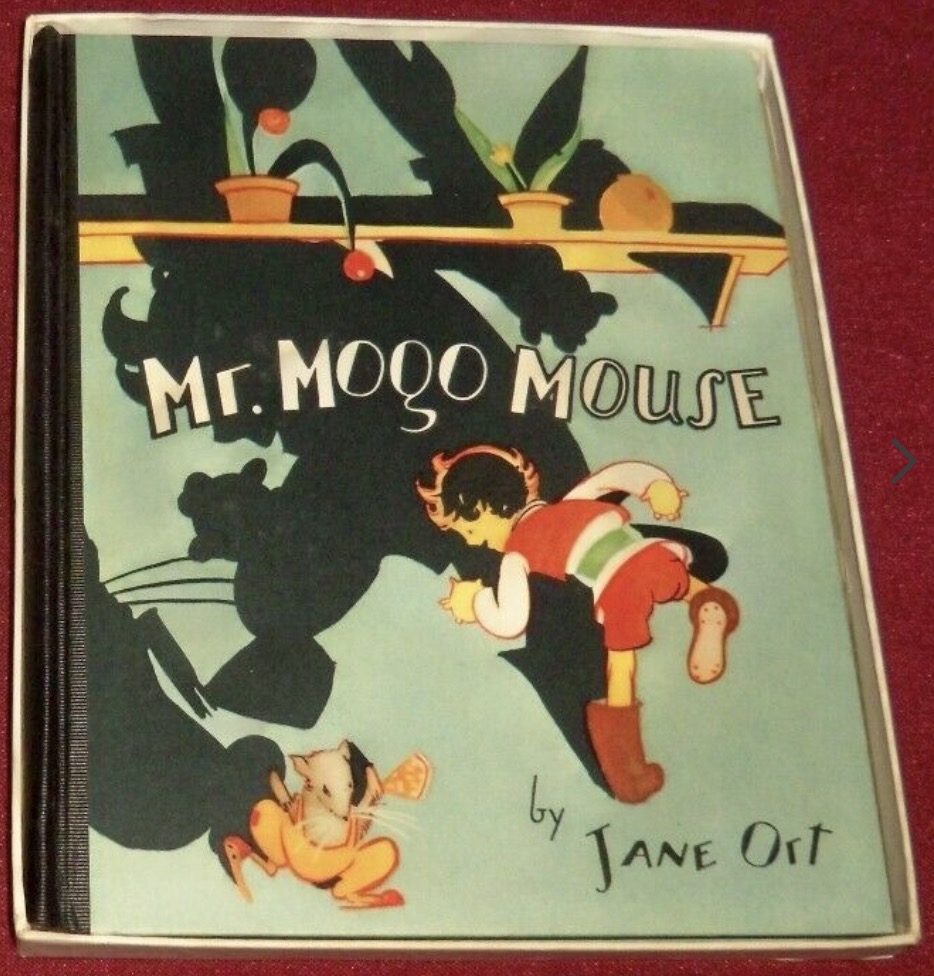

1920s children’s illustrated book.

In a 1924 animated short by Otto Messmer, Felix the Cat uses a mouse as a hunting animal.

At this point, the Felix character was at the peak of his film career. His image could be seen on clocks and Christmas ornaments. Felix also became the subject of several popular songs of the day, such as “Felix Kept Walking” by Paul Whiteman. Sullivan made an estimated $100,000 a year from toy licensing alone. With the character’s success also emerged new costars, including a mouse named Skiddoo.

In Felix Loses Out, a 1924 animated short by Otto Messmer, Felix the Cat uses Skiddoo the mouse as an engine to power his soapbox racer.

In Alice the Whaler, a 1927 Walt Disney movie, Alice is dancing aboard her ship with a veritable zoo of a crew.

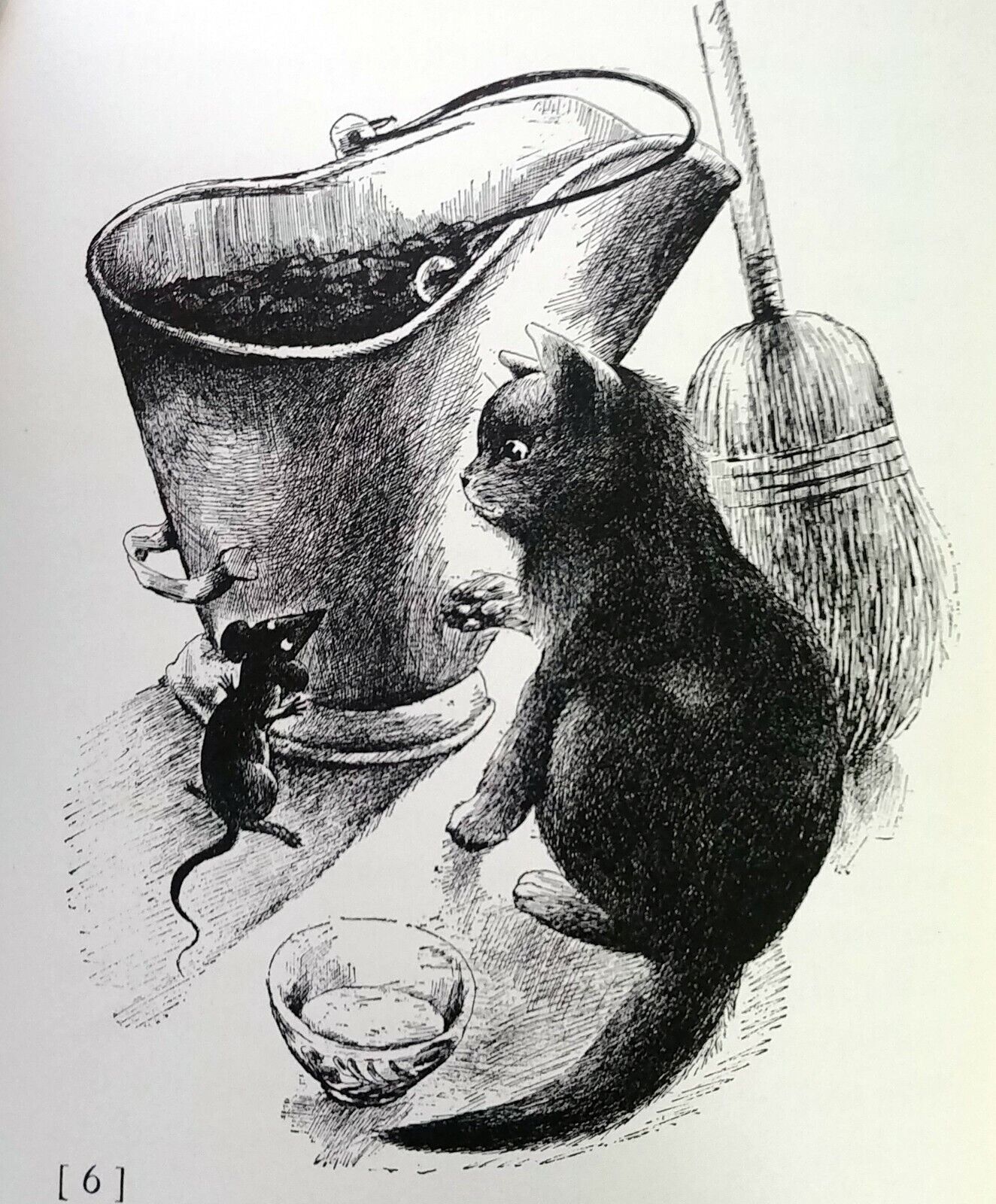

Meanwhile, in the galley, the chef (a cat) is preparing food while his assistant, a mouse, is peeling potatoes. When the chef complains that they need eggs, the mouse is enlisted to retrieve them from the crow’s nest. Hilarity ensues. Note that the mice are wearing short pants — like Mickey will when he first appears not long after this.

POST-MICKEY…

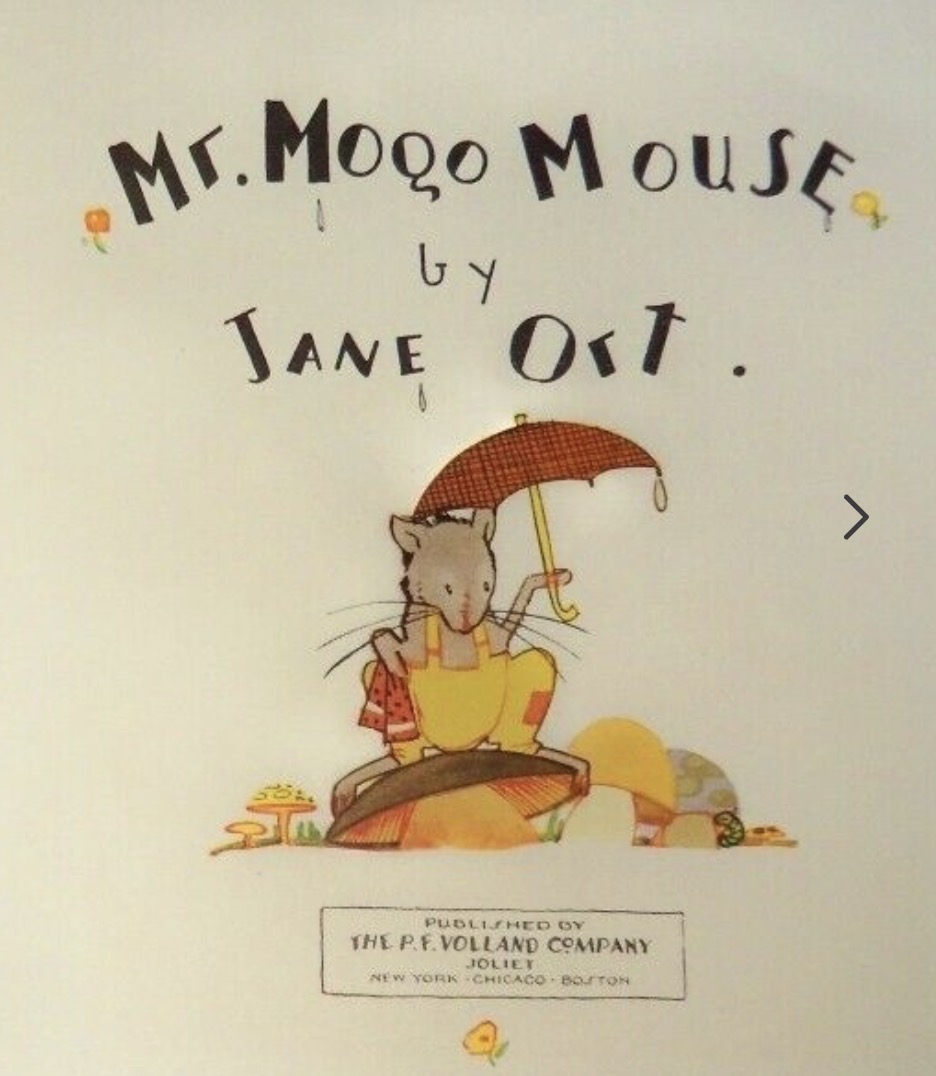

This is a beautifully illustrated Volland title from 1930 about a boy and his mouse friend in Czechoslovakia. The pages were filled with art deco illustrations by Jane Beachy Miller. Miller, who was called “one of New York’s hardest-working young fashion illustrators,” went on to have a successful artistic career illustrating articles for magazines like Good Housekeeping and Ladies Home Journal with her pen-and-ink drawings.

PRE-MICKEY…

As noted in previous MOUSE installments, mice are often depicted living in comically over-crowded conditions. This image is from the 1925 story “The Adventures of a Mouse Family” by K.H. With, from The Field Fourth Reader by Walter Taylor Field. Illustrated by Marguerite Davis and Rodney Thomson.

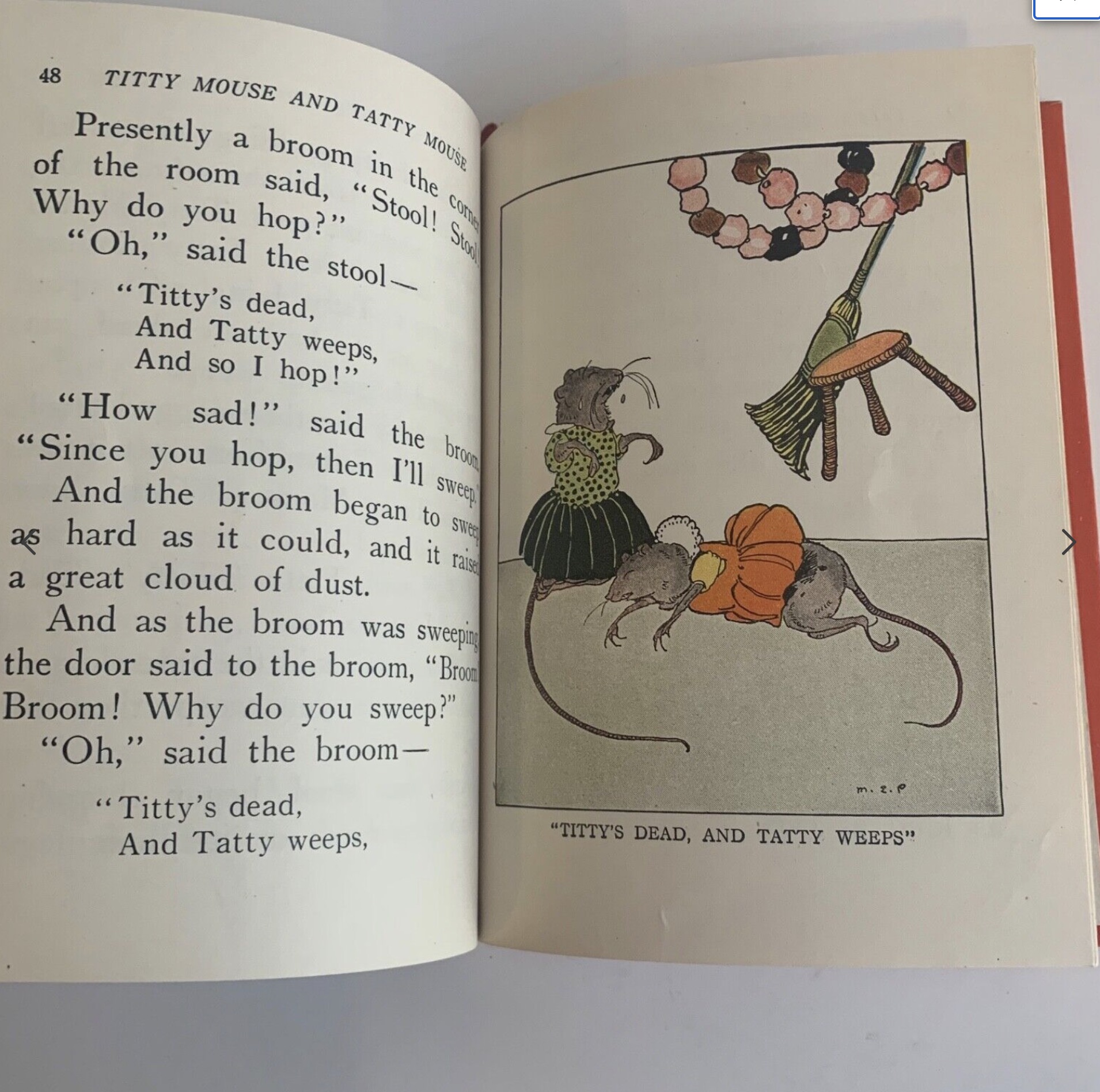

Not really sure how to categorize this 1927 children’s book, which recounts the tory of Titty Mouse, who is scalded to death while making corn pudding. Tatty Mouse, her partner, weeps. Which leads to a chain reaction in which the house shakes itself apart.

POST-MICKEY…

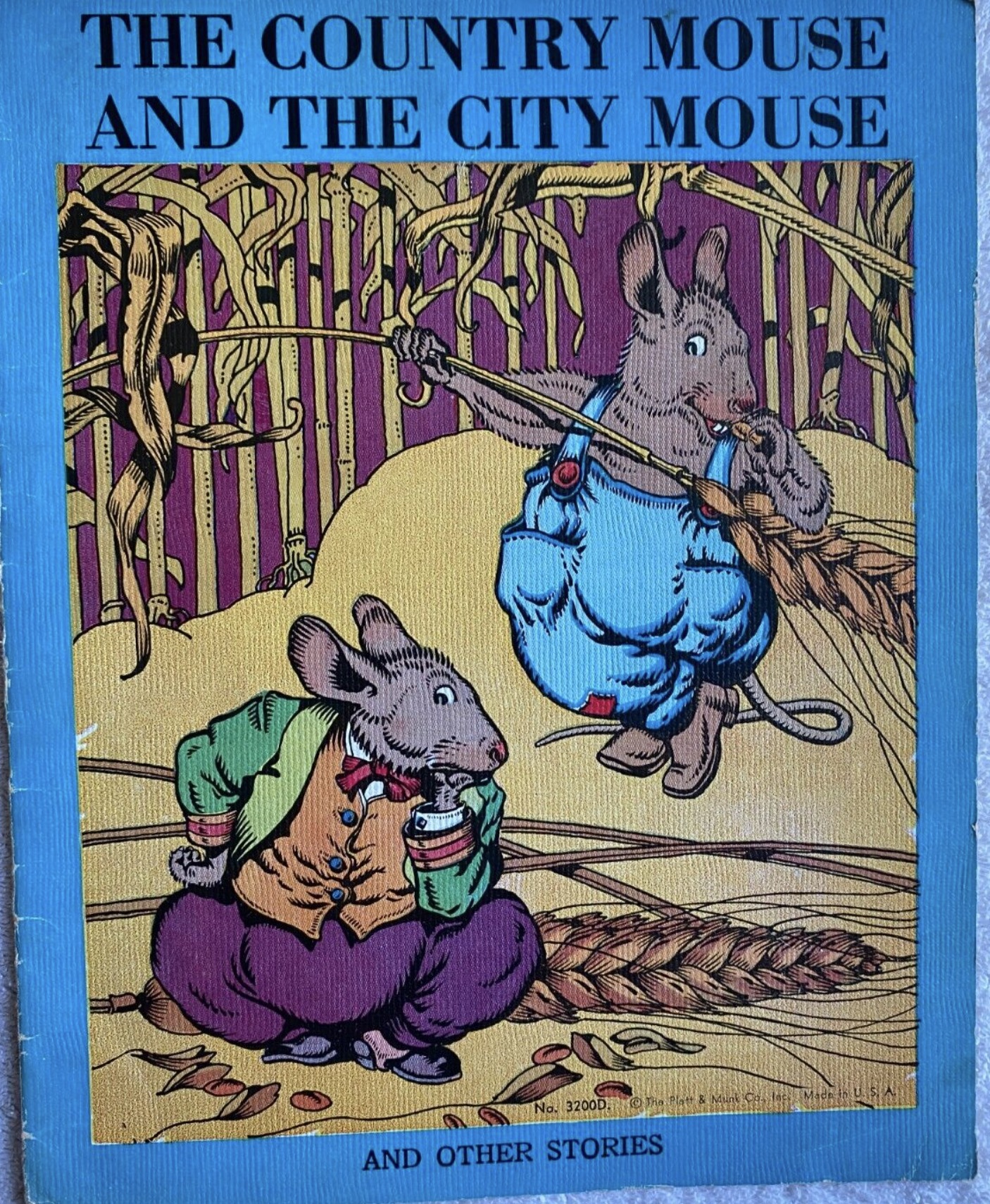

A 1930 edition of this perennial story.

INTRODUCTION by Matthew Battles: Animals come to us “as messengers and promises.” Of what? | Matthew Battles on RHINO: Today’s map of the rhinoceros is broken. | Josh Glenn on OWL: Why are we overawed by the owl? | Stephanie Burt on SEA ANEMONE: Unable to settle down more than once. | James Hannaham on CINDER WORM: They’re prey; that puts them on our side. | Matthew Battles on PENGUIN: They come from over the horizon. | Mandy Keifetz on FLEA: Nobler than highest of angels. | Adrienne Crew on GOAT: Is it any wonder that they’re G.O.A.T. ? | Lucy Sante on CAPYBARA: Let us gather under their banner. | Annie Nocenti on CROW: Mostly, they give me the side-eye. | Alix Lambert on ANIMAL: Spirit animal of a generation. | Jessamyn West on HYRAX: The original shoegaze mammal. | Josh Glenn on BEAVER: Busy as a beaver ~ Eager beaver ~ Beaver patrol. | Adam McGovern on FIREFLY: I would know it was my birthday / when…. | Heather Kapplow on SHREW: You cannot tame us. | Chris Spurgeon on ALBATROSS: No such thing as a lesser one. | Charlie Mitchell on JACKALOPE: This is no coney. | Vanessa Berry on PLATYPUS: Leathery bills leading the plunge. | Tom Nealon on PANDA: An icon’s inner carnivore reawakens. | Josh Glenn on FROG: Bumptious ~ Rapscallion ~ Free spirit ~ Palimpsest. | Josh Glenn on MOUSE.

ALSO SEE: John Hilgart (ed.)’s HERMENAUTIC TAROT series | Josh Glenn’s VIRUS VIGILANTE series | & old-school HILOBROW series like BICYCLE KICK | CECI EST UNE PIPE | CHESS MATCH | EGGHEAD | FILE X | HILOBROW COVERS | LATF HIPSTER | HI-LO AMERICANA | PHRENOLOGY | PLUPERFECT PDA | SKRULLICISM.