PRE-MICKEY MICE (1)

By:

April 10, 2023

An episode of MOUSE, a multi-part installment in the ongoing BESTIARY series.

During 2021–2022, I contributed three BESTIARY series installments, for each of which I conducted research into and offered a top-line analysis of 20th-century pop-culture depictions of a charismatic creature: OWL | BEAVER | FROG. I first developed this approach for an earlier series, TAKING THE MICKEY, which analyzes Mickey Mouse’s evolving significance. Via this new BESTIARY installment, I’ll “read” Mickey within the context of his fellow pop-culture mice.

This multipart BESTIARY series installment, collectively titled MOUSE, is divided up as follows: MOUSE (INTRO) | PRE-MICKEY MICE (1904–1913) | PRE-MICKEY MICE (1914–1923) | PRE-& POST-MICKEY MICE (1924–1933) | POST-MICKEY MICE (1934–1943) | POST-MICKEY MICE (1944–1953) | POST-MICKEY MICE (1954–1963) | POST-MICKEY MICE (1964–1973) | POST-MICKEY MICE (1974–1983) | POST-MICKEY MICE (1984–1993) | POST-MICKEY MICE (1994–2003).

(1904–1913)

According to HILOBROW’s periodization scheme, the cultural era known as the nineteen-oughts/aughts begins c. 1904 and ends c. 1913. During this period, let’s see how the mice tropes — surfaced via this audit, and dimensionalized in the series’ introduction — shake out via pop culture.

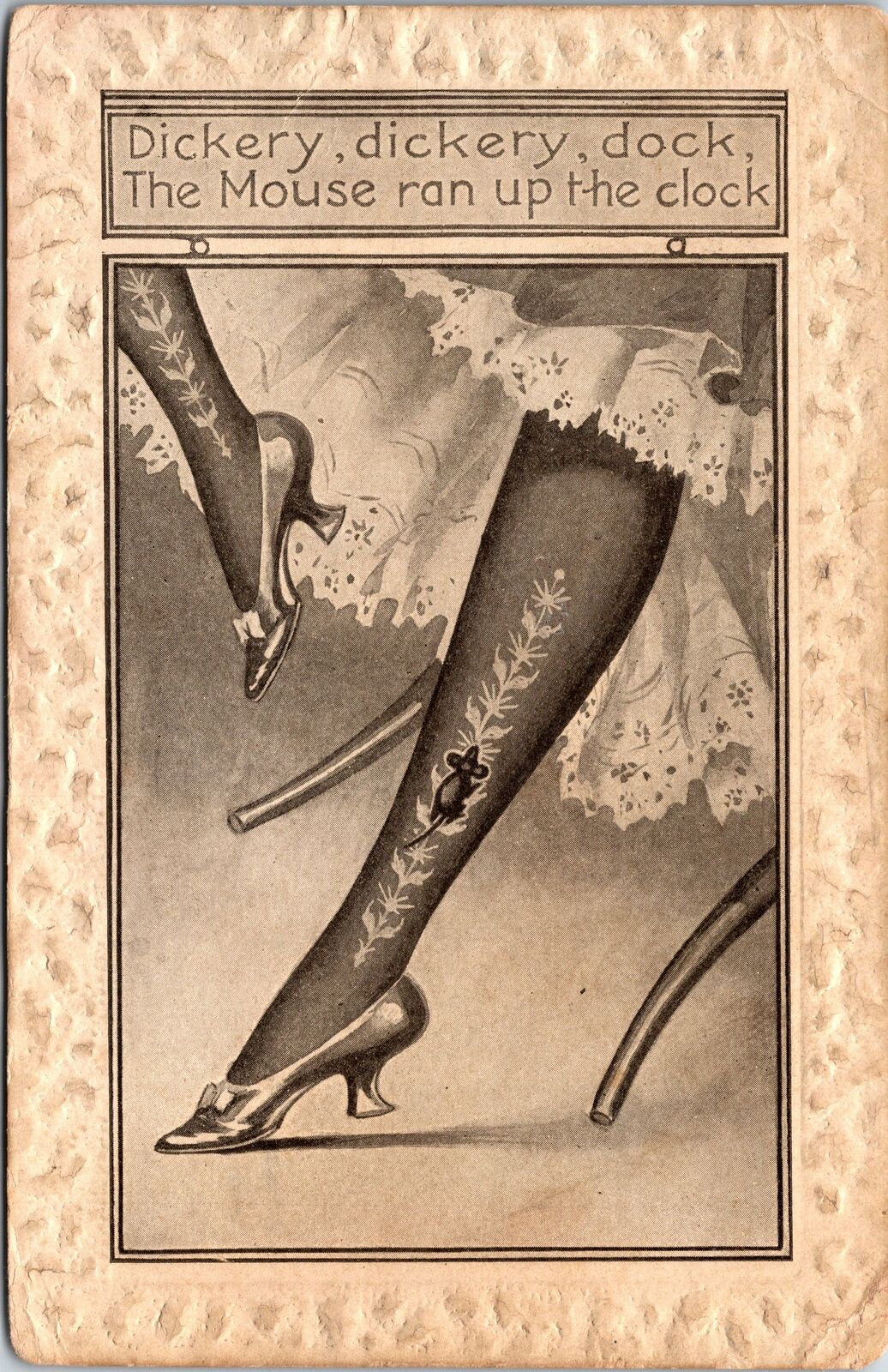

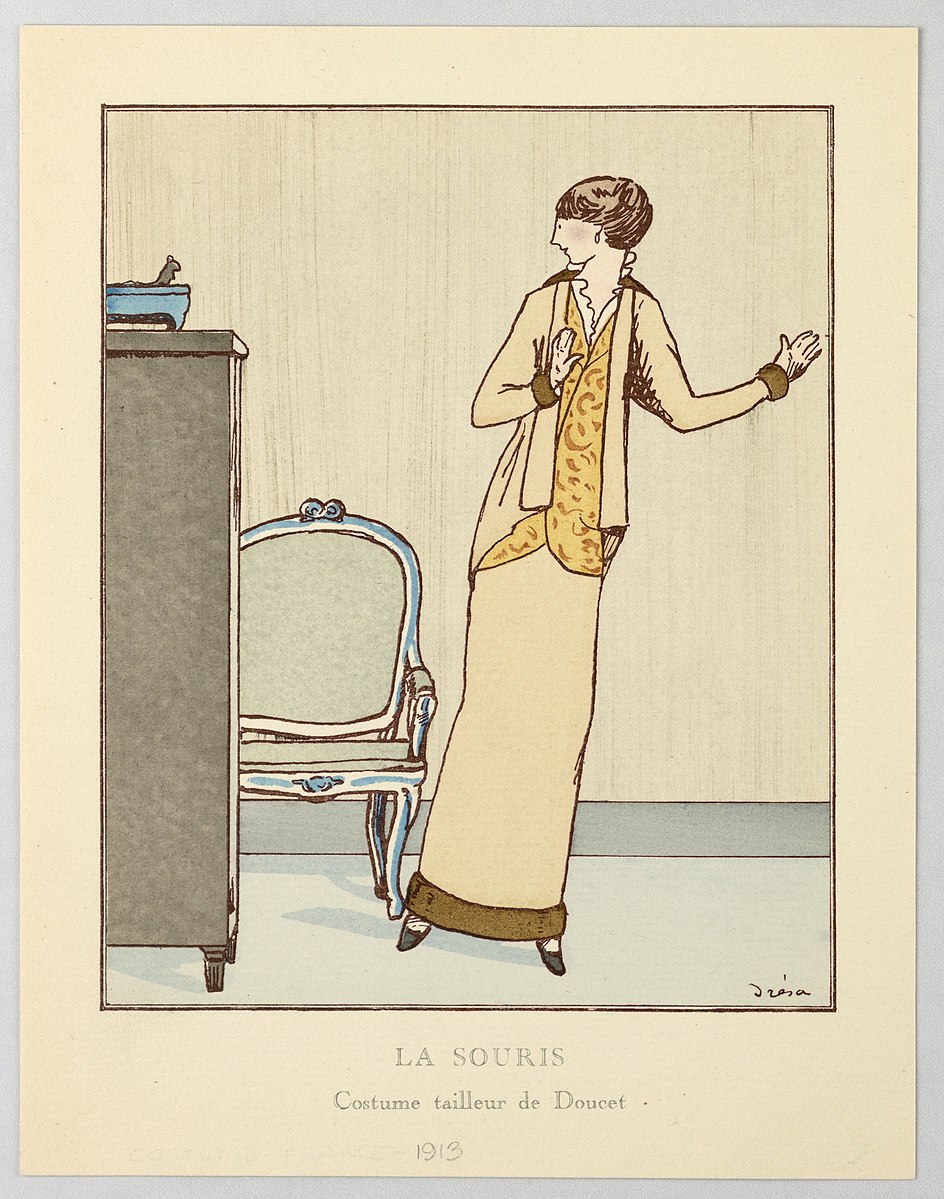

Potcards (and a stereoview) c. 1904–1913

In The Marvelous Land of Oz (1904), Scarecrow and his friends enter his palace (taken by rebels), and are captured immediately, to be brought before their leader. However: the rebels are all women and Scarecrow has recently met the Queen of the Field Mice and asked for permission to take a few of her subjects along.

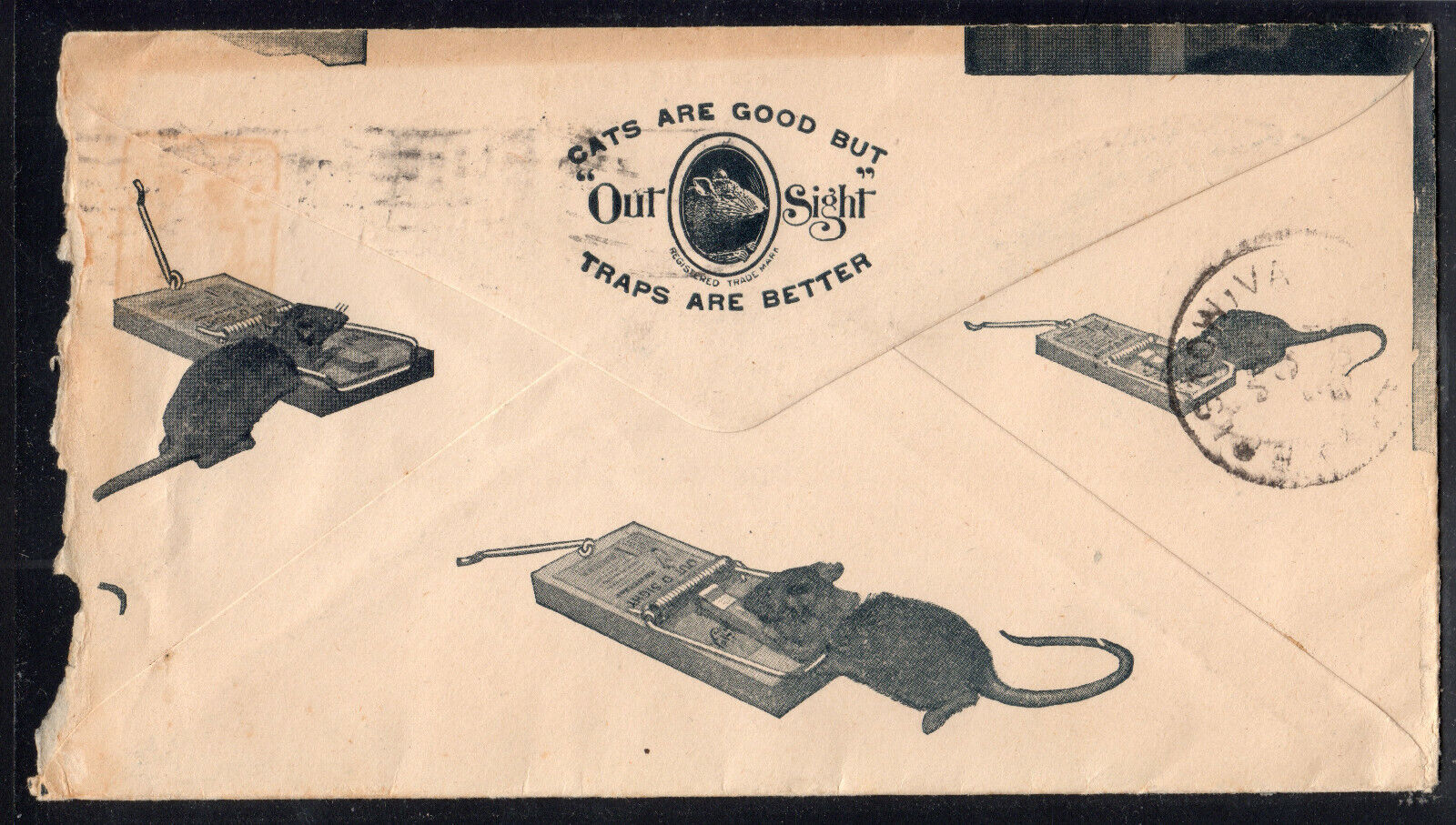

Above: 1905 mousetrap manufacturer’s (gruesome) commercial mailing.

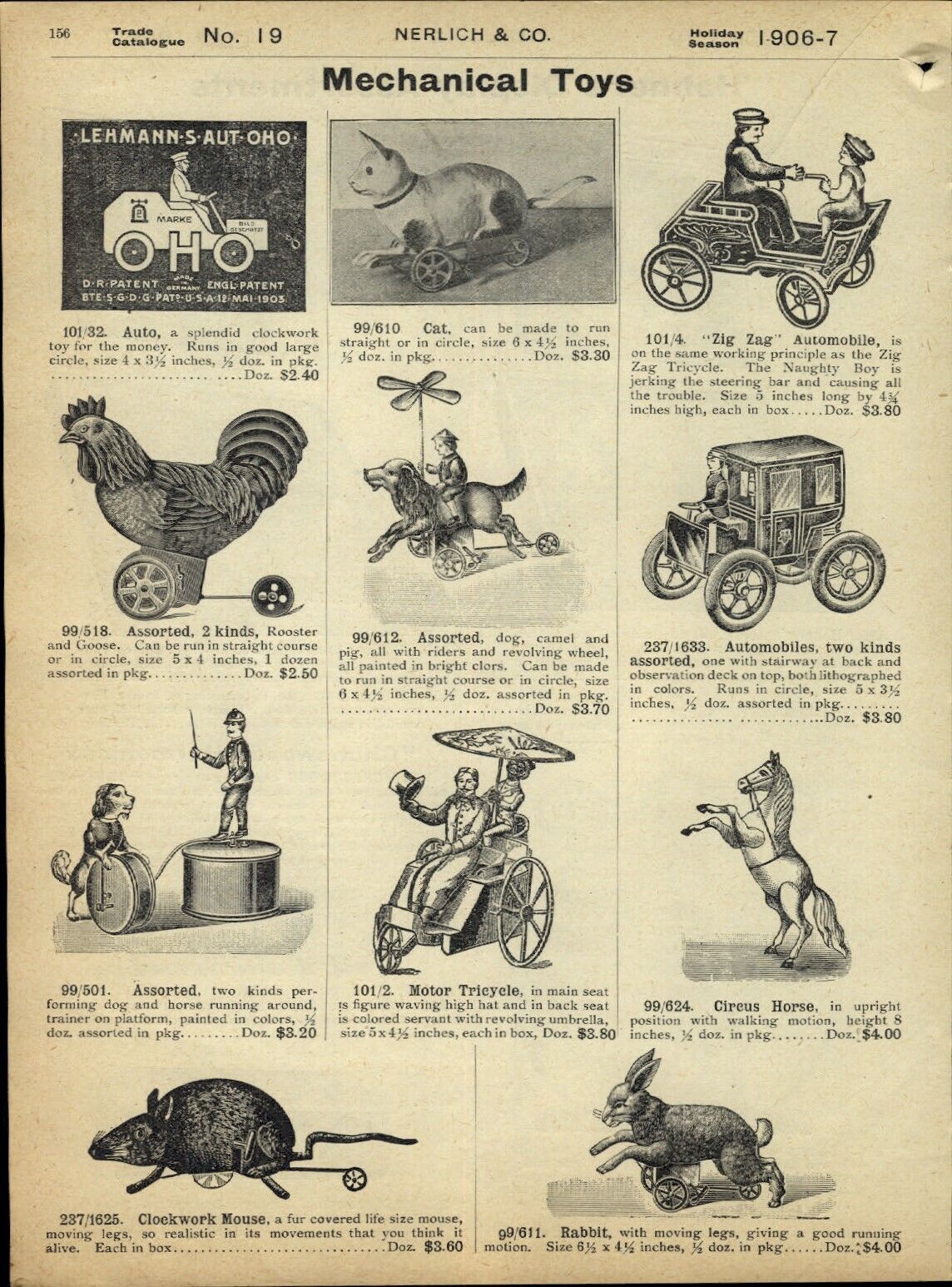

A 1907 catalog featuring a clockwork mouse toy.

Looks like the clockwork mouse first scampered into toystores c. 1850. True? In an 1852 issue of Hogg’s Instructor, we find a British writer complaining that French mechanical toys are far too complex for English toymakers — even English watchmakers. “Few watchmakers here can repair a clockwork mouse.”

PS: Although Google would have us believe that a mechanical mouse is advertised in a 1773 publication called Amateur Work, Illustrated — I believe this is misdated. I think it’s from the 1880s.

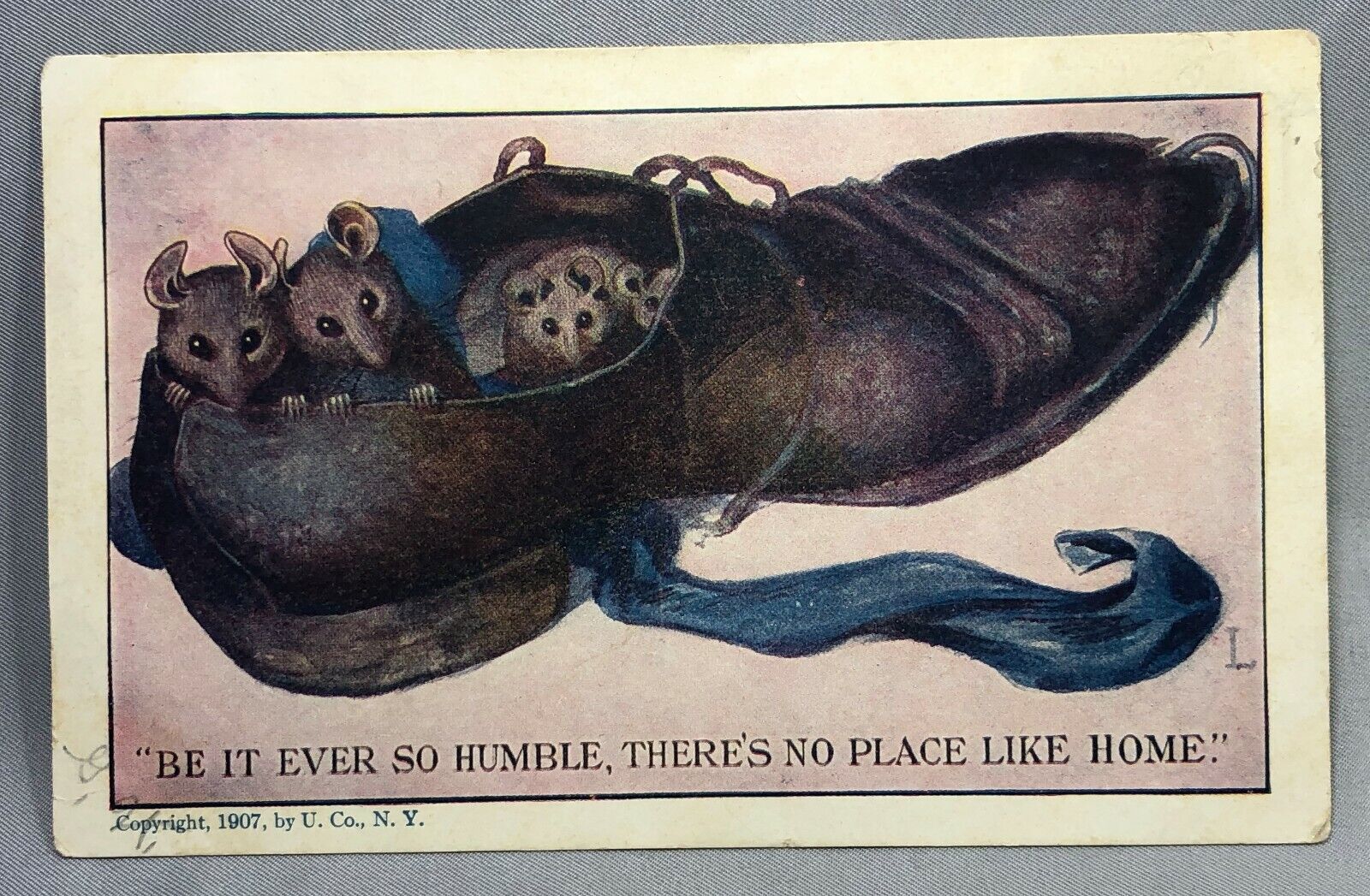

Not sure when this trope first appears, but we’ll often find large mouse families in overcrowded, makeshift “houses” — which one has to imagine is some sort of political commentary on poverty, immigrants, etc. The postcard above is from 1907.

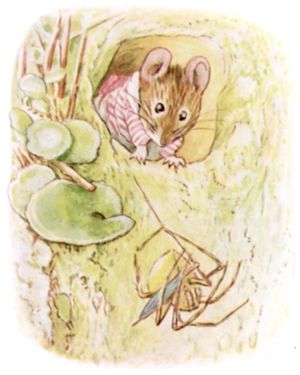

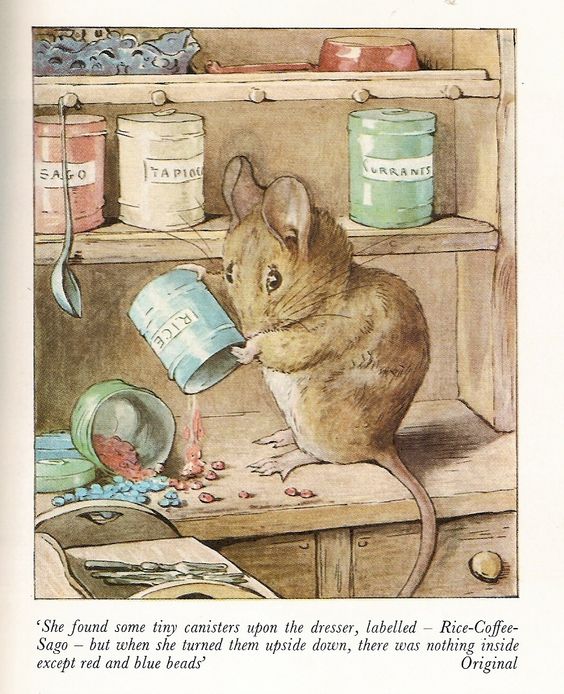

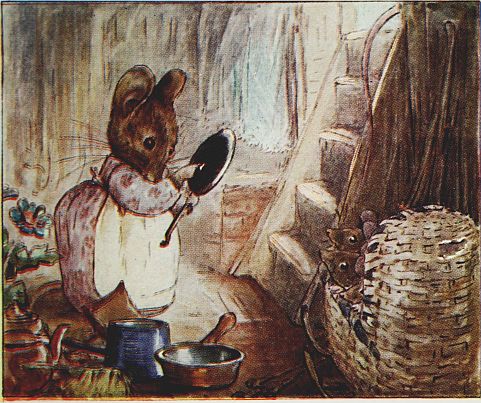

Always a contrarian when it comes to the character of mice (see Hunca Munca), in The Tale of Mrs. Tittlemouse (1910), Beatrix Potter has Mrs. Thomasina Tittlemouse (who debuted in 1909 in a small but crucial role in The Tale of The Flopsy Bunnies) work tirelessly to keep her dwelling tidy. These efforts are thwarted by insect and arachnid intruders who create all sorts of messes about the place; the abject always returns.

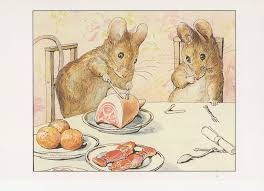

Beatrix Potter’s The Tale of Two Bad Mice (1904) is the early twentieth century’s most important example of the Mouse as Rebellious Scamp trope. (Read it here.) Here we find two adorable mice — Hunca Munca and her mate — vandalizing a fussy Victorian dollhouse in a kind of anarchic, proto-punk frenzy — smashing dishes, throwing clothing out the window, shredding the down comforter. Wow! What audiences at the time — mollified, one imagines, by the story’s tacked-end contrite ending — didn’t know was that the author at that very moment in her life yearned to free herself of her domineering parents, who’d groomed her to be their home’s permanent resident and housekeeper.

I’d also add that there’s a phildickian/Truman Show aspect to this story. What sets the mice off is the fact that all this domestic splendor turns out to be an illusion and a sham: “Hunca Munca tried every tin spoon in turn; the fish was glued to the dish. Then Tom Thumb lost his temper. He put the ham in the middle of the floor, and hit it with the tongs and with the shovel — bang, bang, smash, smash!”

One more note: HILOBROW friend Annalee Newitz has credited this Beatrix Potter story with helping to inspire the rebellious talking animals of her latest sf novel, The Terraformers (2023).

The 1907 children’s book The Cock, the Mouse, and the Little Red Hen — written by Félicité Lefèvre and illustrated by Tony Sarg — tells the story of a lazy mouse and rooster who sponge off a little red hen, refusing to help out with any chores. They get their comeuppance when a fox nearly kills them all. An American fable and motivational tool suggesting we reap what we sow, it was first collected by Mary Mapes Dodge in St. Nicholas Magazine in 1874. Similar to Aesop’s “The Ant and the Grasshopper.”

Two notes: I’m shoe-horning this one into REBELLIOUS SCAMP — the mouse may rebel against the Hen’s benevolent dictatorship, but he’s not scamp, just a slacker. Also, he looks very much like a rat.

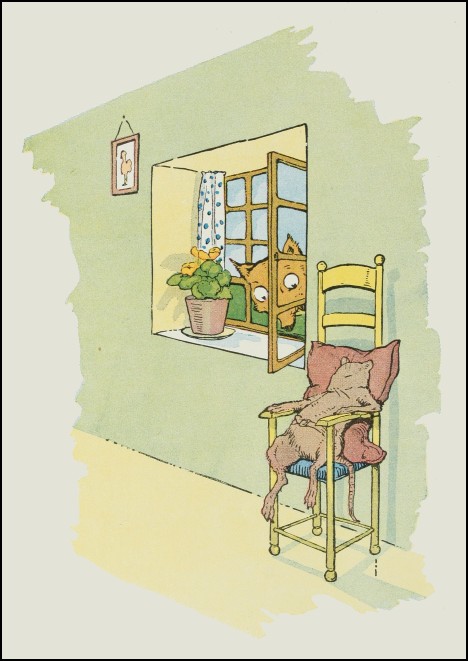

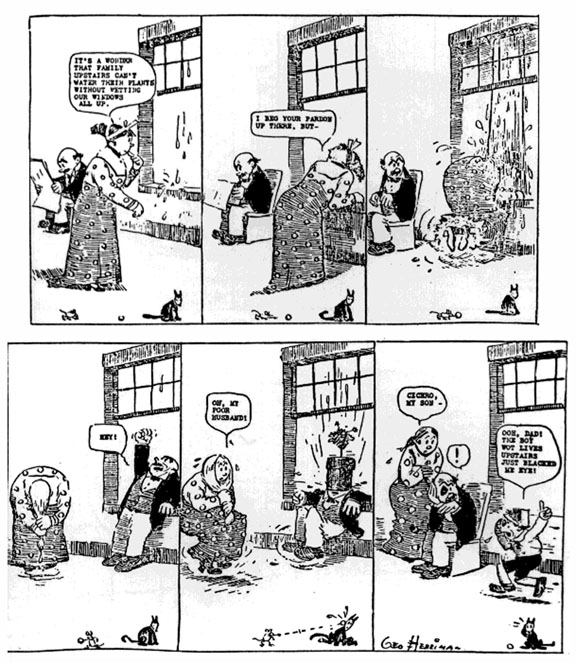

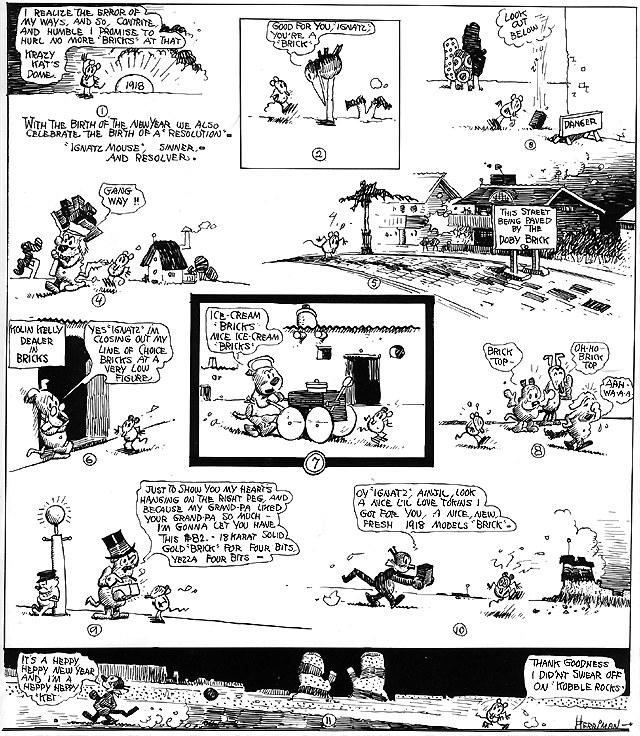

The Dingbat Family (also The Family Upstairs) is a comic strip by George Herriman that ran from June 1910 to January 1916. It introduced Krazy Kat and Ignatz Mouse, whose slapstick antics appeared in the bottom of each strip. The mouse is from upstairs, and it continually attacks and pesters the downstairs cat.

Eugene Field’s story “The Mouse and the Moonbeam” is a story told by Miss Mauve Mouse, whose rebellious sister Squeaknibble — who has a “disposition to sneer at some of the most respected dogmas in mousedom,” for example the notion that the moon is made of green cheese; and who doesn’t believe in an “archfiend” (a cat), nor in Santa Claus — is horribly killed by a cat disguised as Santa Claus. The story is from the 1880s; the illustration above is from 1912. A cautionary tale by the author of “Wynken, Blynken, and Nod” and “Little Boy Blue.”

George Herriman’s comic strip Krazy Kat first appeared in the New York Evening Journal in 1913. Wildly popular, it would run until 1944. The strip focuses on the relationship between a guileless cat named Krazy and Ignatz, a short-tempered mouse. Krazy nurses an unrequited love for the mouse. However, Ignatz despises Krazy and constantly schemes to throw bricks at Krazy’s head, which Krazy interprets as a sign of affection. (In 1924, Gilbert Seldes would call Krazy Kat “the most amusing and fantastic and satisfactory work of art produced in America today.”)

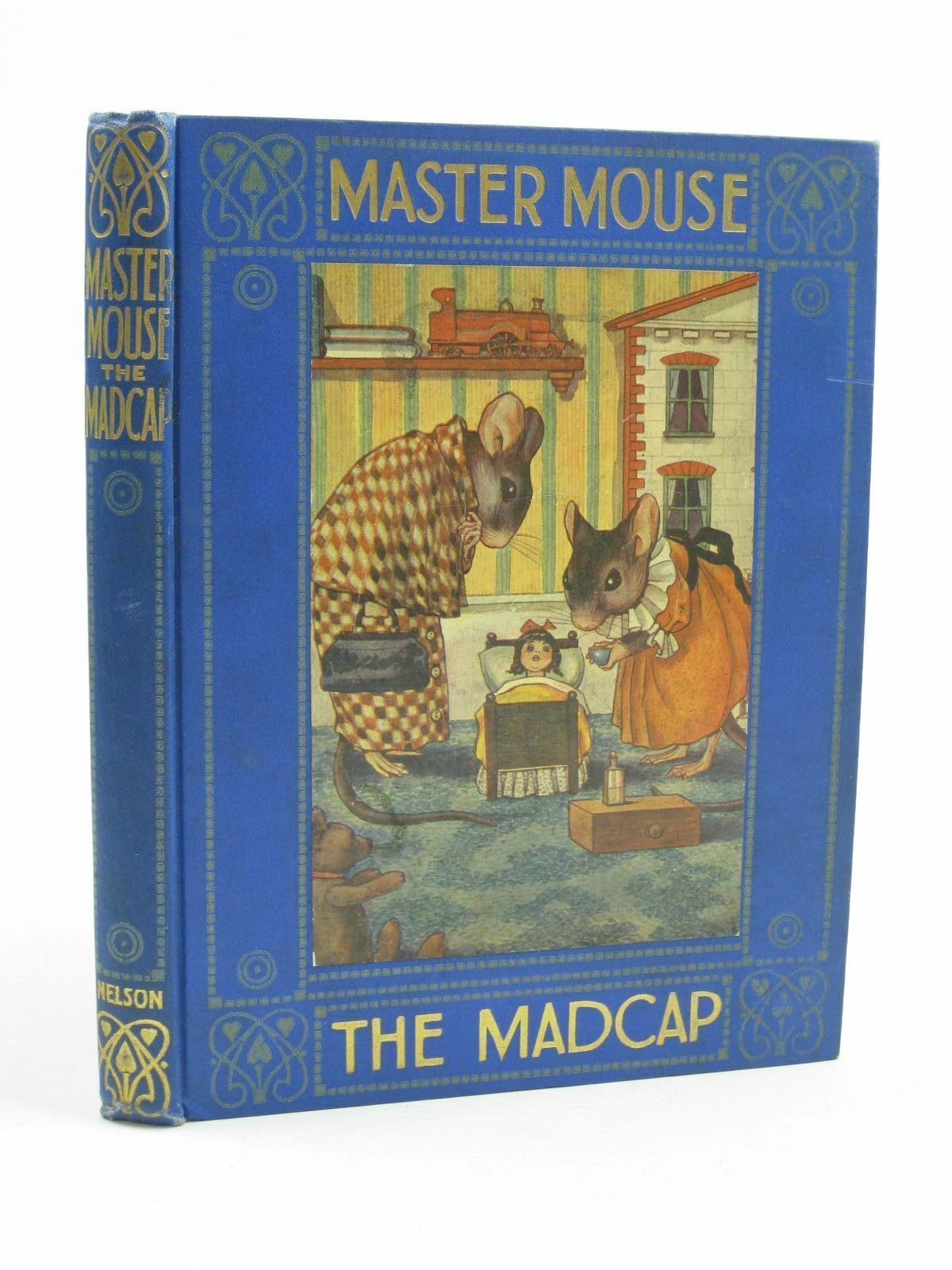

A 1913 children’s book, by Jacqueline Clayton, about a mischievous mouse. Also see The Georgie-Porgie Book (1912) by the same author. With illustrations by Margaret Clayton.

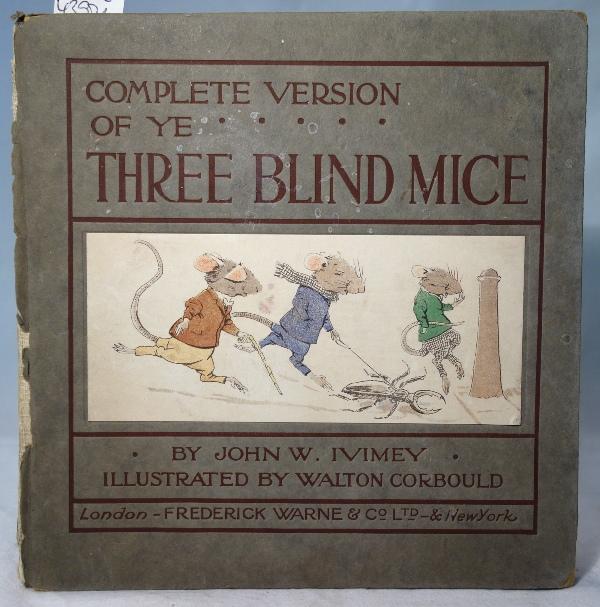

The Complete Version of Ye Three Blind Mice, a 1904 English illustrated children’s book by John W. Ivimey, offers us a novel take on the “Three Blind Mice” rhyme — which first became popularized among children during the 19th century. Here, the mice are mischievous characters who seek adventure, only to be blinded by brambles (ugh!) when the farmer’s wife chases them out of the house. There’s a tacked-on happy ending in which they regain their eyesight and find good, honest work.

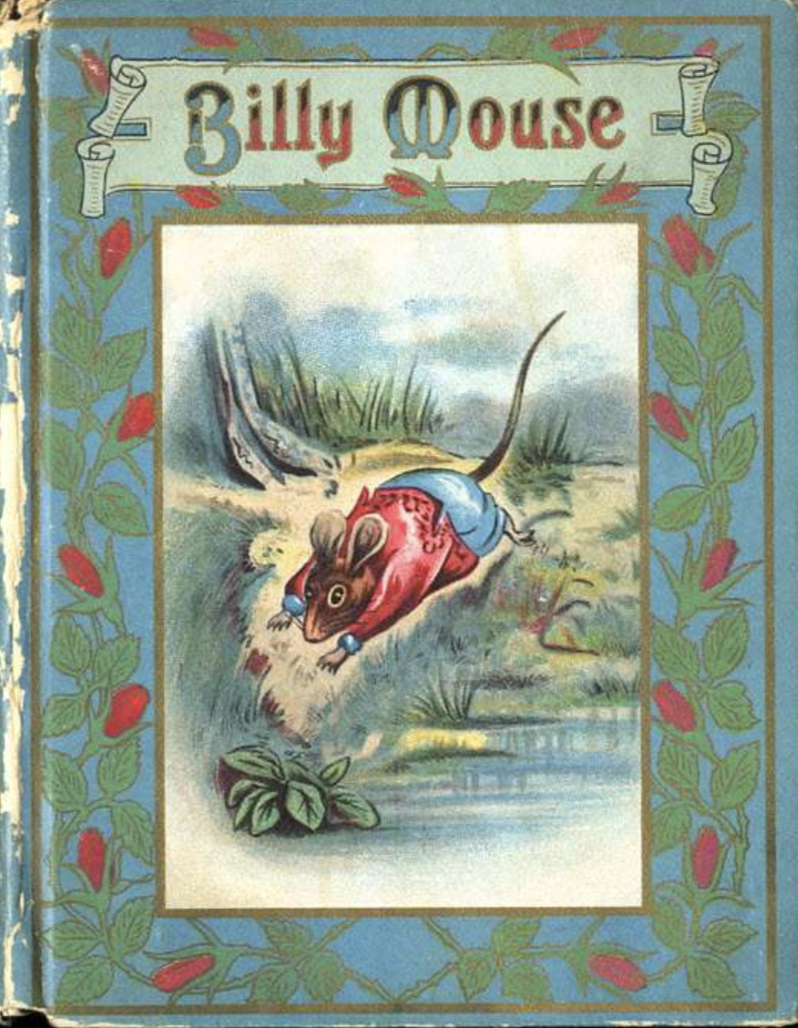

I haven’t read Billy Mouse and the Lucky Stone, a 1907 children’s book written and illustrated by Arthur Layard. But it certainly seems to be about an intrepid adventurer. Ninety years later: Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone.

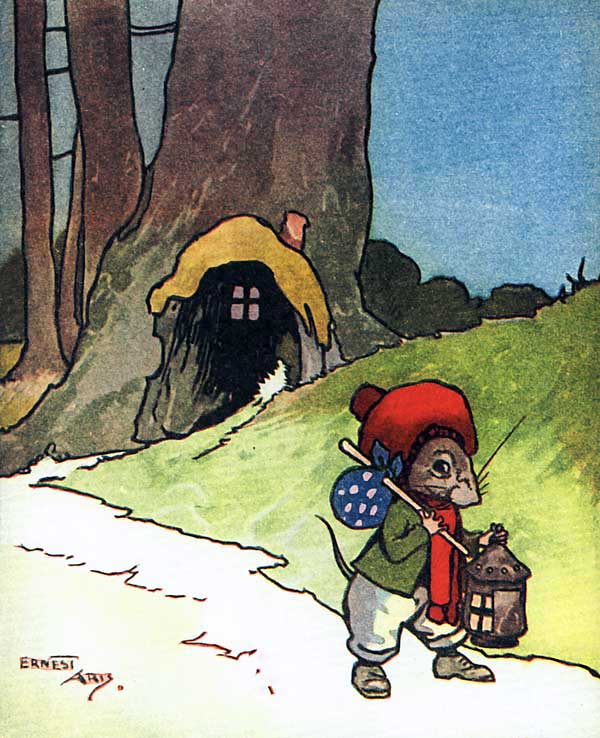

Ernest Aris, also known by the pen names Robin A Hood and Dan Crow, (1882–1963), was a prolific writer and illustrator who worked on hundreds of children’s books — as well as cigarette cards, postcards, toys and games. (He created Cococubs — a wildly popular set of hollowcast hand-painted lead figures of anthropomorphic creatures given away with Cadburys Bournville Cocoa from 1934 to 1939.)

He illustrated many mouse books. These include: Willie Mouse (1912), Wee Jenny Mouse (1912), A Tale of a Bold Bad Mouse (1916; an homage, perhaps, to Beatrix Potter’s 1904 The Tale of Two Bad Mice), That Little Grey Mouse (1916), Mother Mouse (1918), Little Mousey Muffet (1923). The anthropomorphic Willie Mouse was a recurring character, featured in Aris’s tales, Cococubs, cigarette cards, and board games. Also: Simon Fatty Mouse.

Note that in Beatrix Potter’s The Tale of Two Bad Mice (1904), Hunca Munca ends up stealing a few items for use in her own home. See REBELLIOUS SCAMP section.

Shown above: a 1905 optical illusion card showing a mouse making its escape.

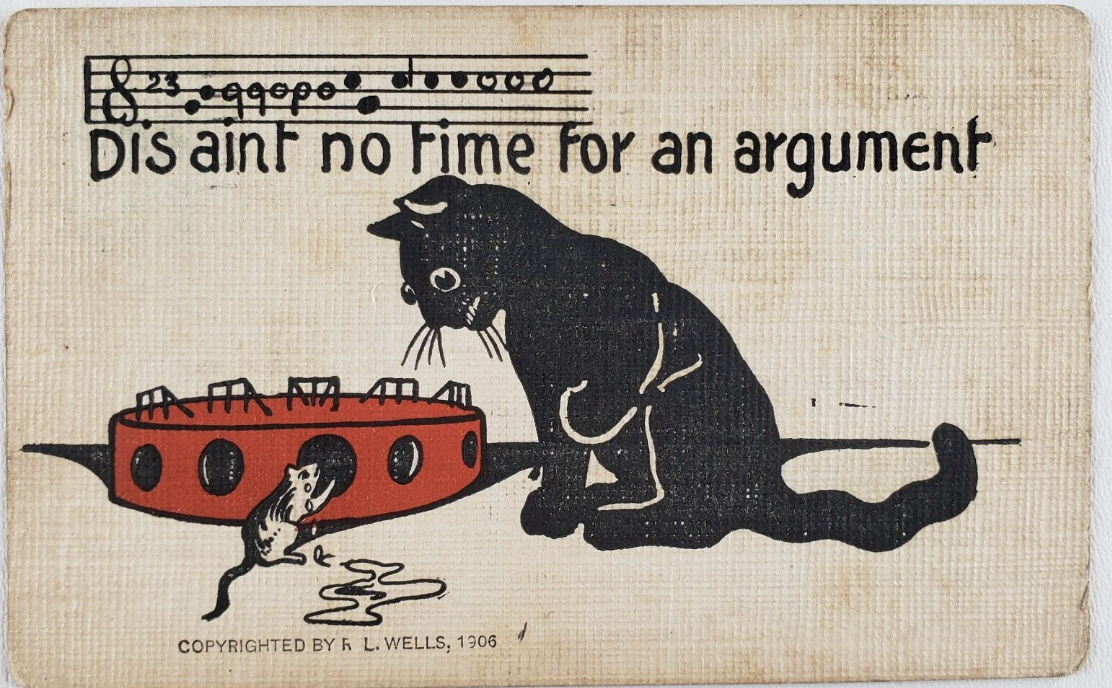

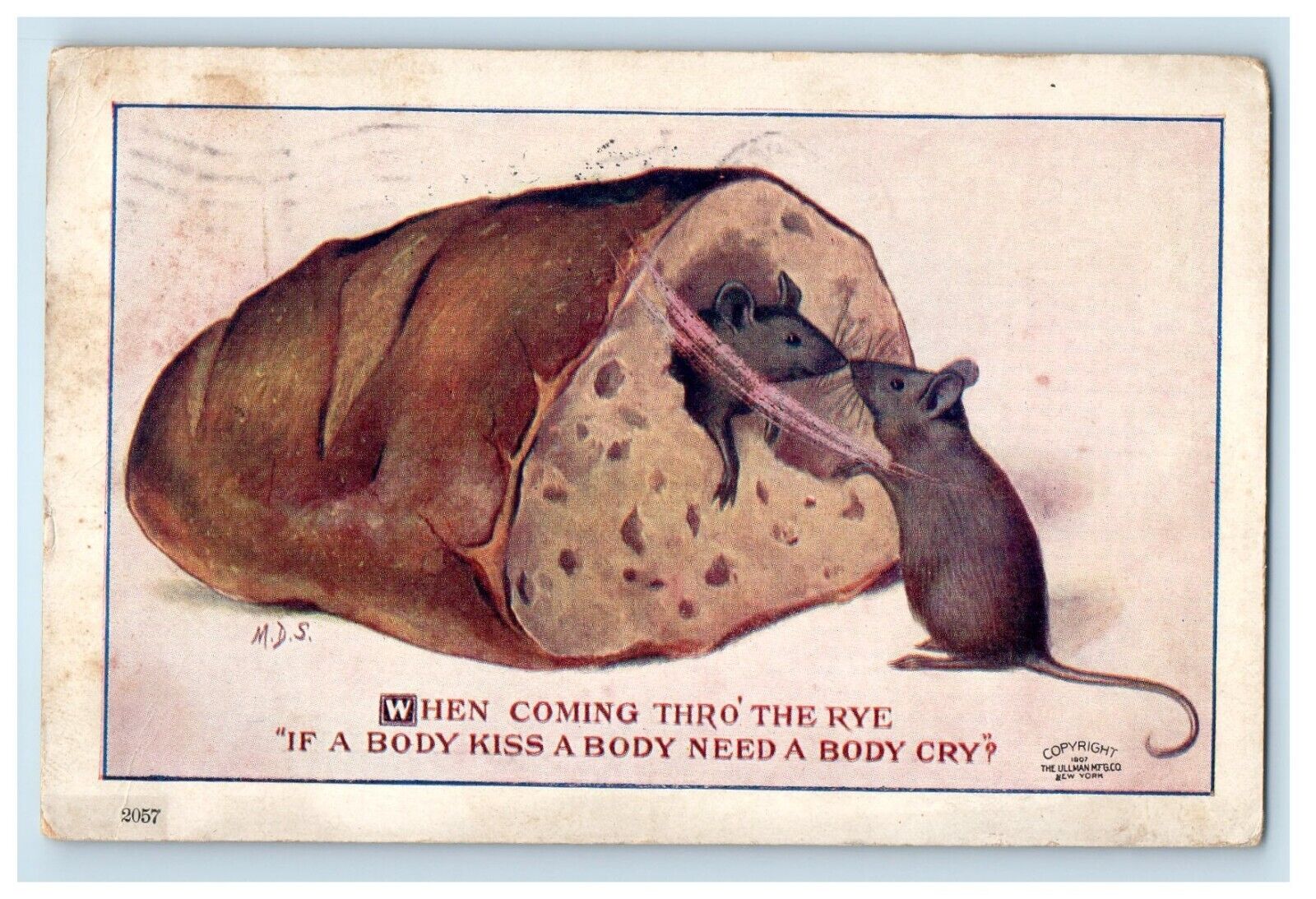

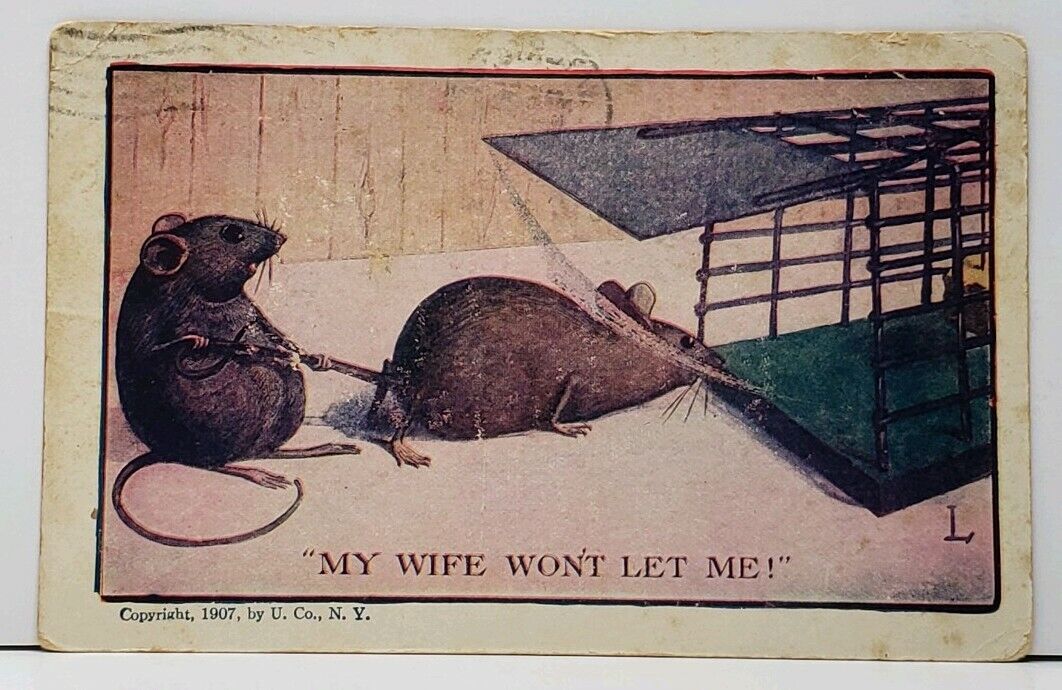

Above: Postcards c. 1904–1913. (The “My Wife Won’t Let Me!” postcard illustration seems to have been stolen from Four Wee Mice: A Story for Children, a 1908 book by “Uncle Milton,” illustrated by M.D.S.) One suspects that the punchline comes from a Florrie Forde song of 1906, about a young lady left at the altar… because the groom’s wife won’t let him marry her.

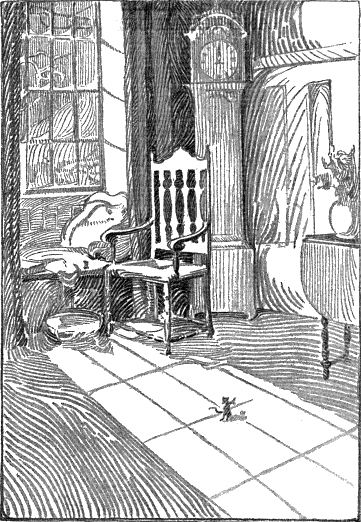

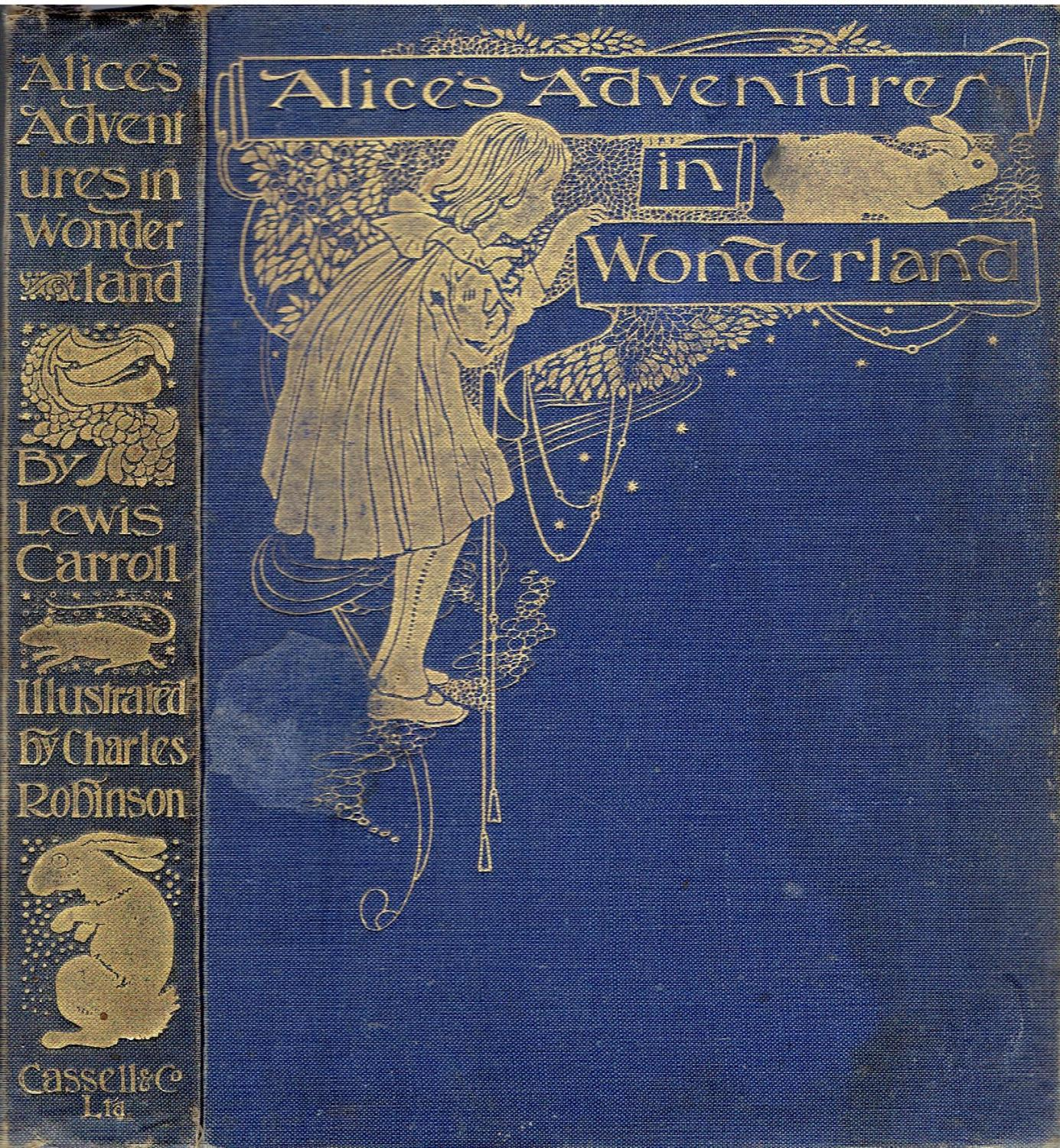

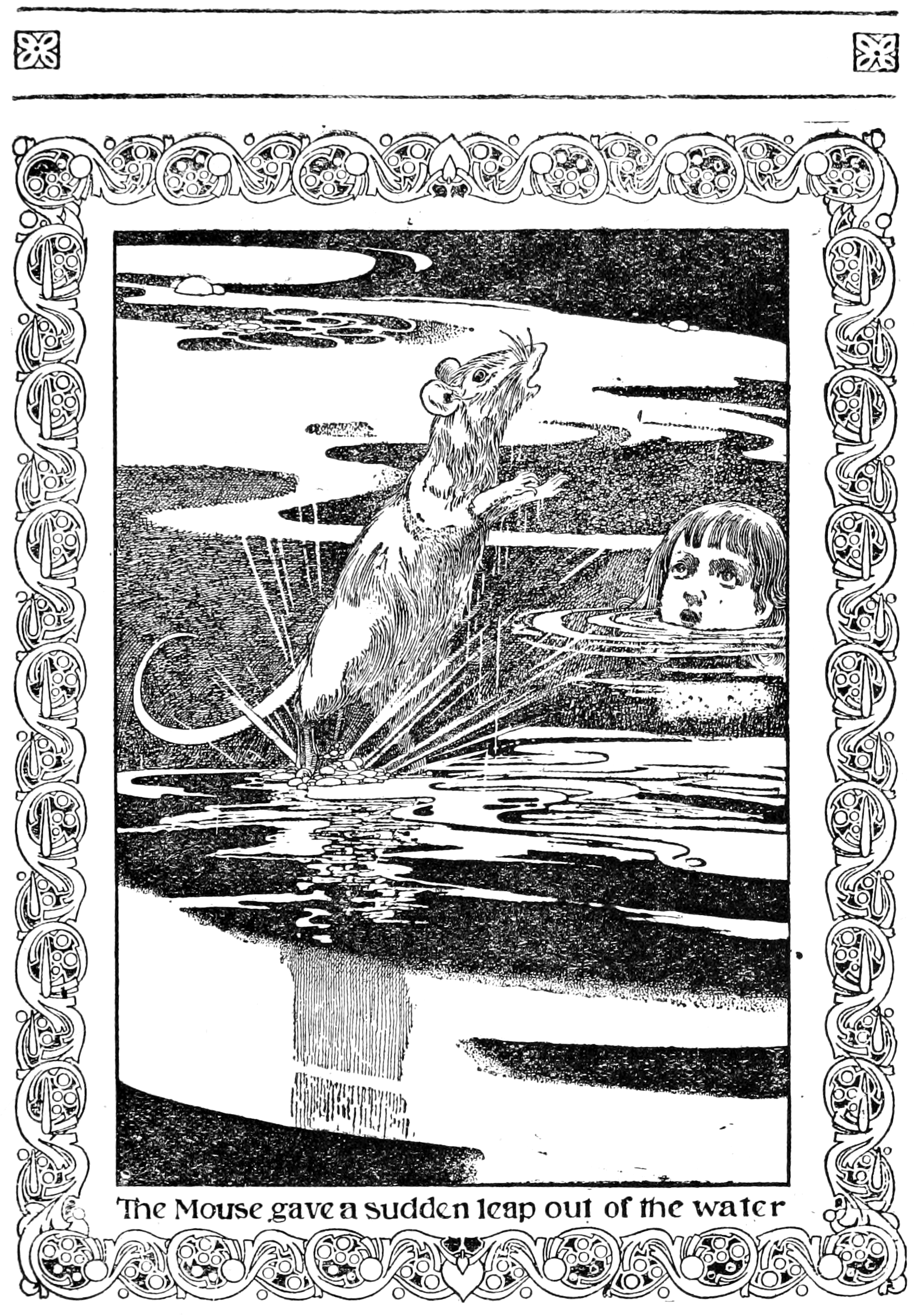

A 1907 edition (now very rare) of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, illustrated by Charles Robinson. Lewis Carroll’s book was published in 1865, so this doesn’t really concern us here. Can you find the mouse on the book’s spine? In addition to the Dormouse, we find a character called the Mouse in chapters 2 and 3 — the shrunken-down Alice finds a mouse floating in a pool of her own tears. Unlike the mice who consort with fairies and brownies, this one wants nothing to do with Alice. It tells a story about how a dog tried to murder it, and flees whenever she mentions her cat.

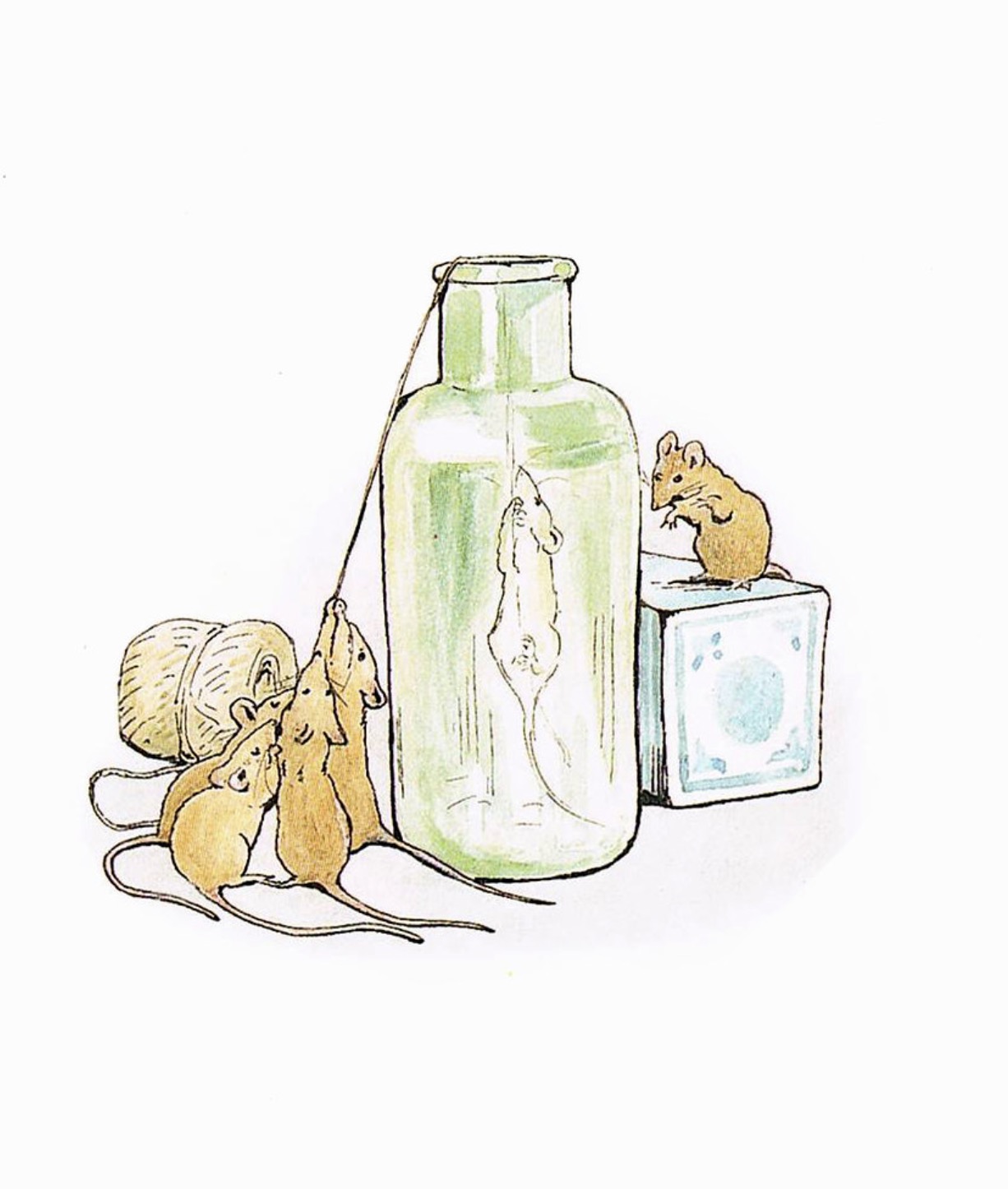

“Mouse helped out of jar,” from Beatrix Potter’s The Tale of Ginger and Pickles (1909). The irony of the tale lies in two predatory animals (Ginger is a tomcat, Pickles a terrier) operating a shop for what would be their natural prey (rabbits, mice, etc.) yet the two are unable to succeed in the venture because of their propensity for extending unlimited credit.

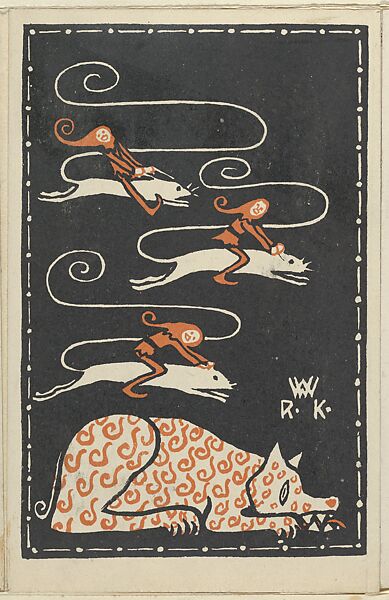

The 1907 image above, by Austria’s Rudolf Kalvach, doesn’t depict anthropomorphized mice… but it’s worth including here because it shows mice collaborating with brownies, elves, or fairies — a trope we’ll come across again. One assumes it’s a pre-20th century trope.

Four Americans make a solemn pact to combat tyranny and save human lives. Thus begins the Secret Order of the White Mice. A 1909 adventure novel by Richard Harding Davis. Note that the book begins with a retelling of Aesop’s fable of the lion and the mouse. The adventurers get their name from a helpful mouse lives on a submarine: “He bunks in the engine-room, and when he smells sulphuric gas escaping anywhere he squeals; and the chief finds the leak, and the ship isn’t blown up. Sometimes, one little, white mouse will save the lives of a dozen bluejackets.” The moral of the story, another character says, is: “Everybody, no matter how impecunious, can help; even you fellows could help. So could I.”

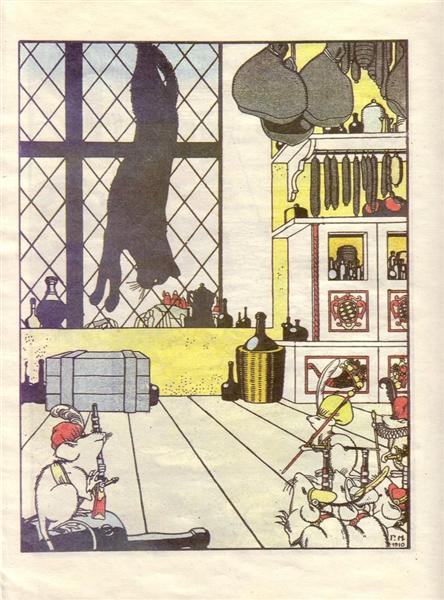

Illustration for Иллюстрация к книге “Как мыши кота хоронили” Жуковского (How Mice Buried the Cat), a 1910 Russian children’s book by Zhukovsky (the foremost Russian poet of the 1810s), illustrated by Heorhiy Narbut — cool Art Nouveau illustrations. I guess the Tsar was not paying attention….

Above: Publicity still from Arthur Carr’s play A Country Mouse, Grand Opera House, Seattle (1905).

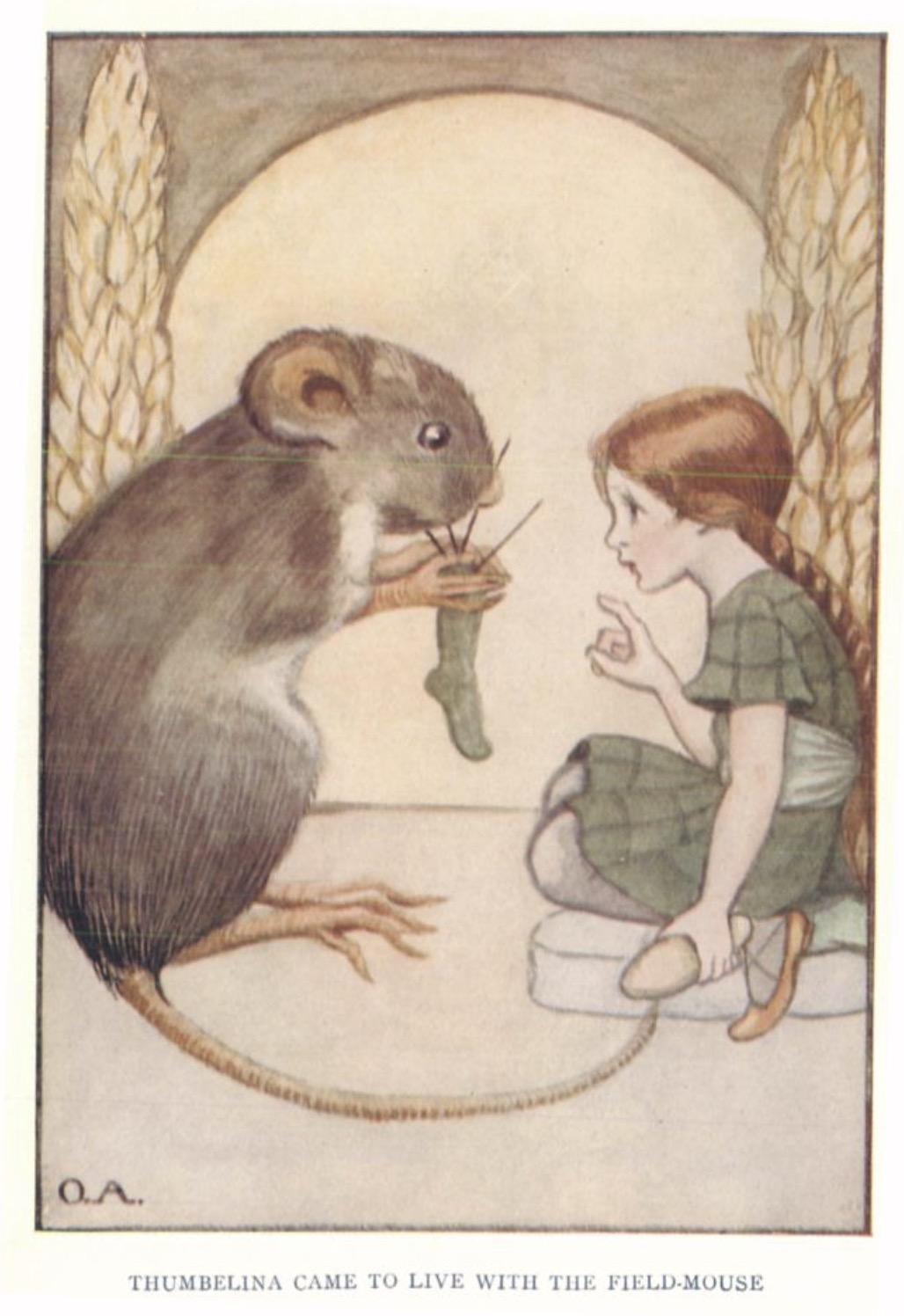

I mentioned above that the “field mouse” has since Aesop’s day been used as a metaphor for the rural, unmodern, traditionalist type. In Hans Christian Andersen’s Little Tiny or Thumbelina, we find a tiny young woman taken in by a kindly field mouse (after she is abducted by a horrible toad — see FRIGHTENING FROGS). However, eventually the field mouse tries to force Thumbelina into marriage with a mole.

The image above is from Childhood’s Favorites and Fairy Stories (1909). Various illustrators.

Hope you enjoyed this first installment in MOUSE. Coming up next: PRE-MICKEY MICE (1914–1923).

INTRODUCTION by Matthew Battles: Animals come to us “as messengers and promises.” Of what? | Matthew Battles on RHINO: Today’s map of the rhinoceros is broken. | Josh Glenn on OWL: Why are we overawed by the owl? | Stephanie Burt on SEA ANEMONE: Unable to settle down more than once. | James Hannaham on CINDER WORM: They’re prey; that puts them on our side. | Matthew Battles on PENGUIN: They come from over the horizon. | Mandy Keifetz on FLEA: Nobler than highest of angels. | Adrienne Crew on GOAT: Is it any wonder that they’re G.O.A.T. ? | Lucy Sante on CAPYBARA: Let us gather under their banner. | Annie Nocenti on CROW: Mostly, they give me the side-eye. | Alix Lambert on ANIMAL: Spirit animal of a generation. | Jessamyn West on HYRAX: The original shoegaze mammal. | Josh Glenn on BEAVER: Busy as a beaver ~ Eager beaver ~ Beaver patrol. | Adam McGovern on FIREFLY: I would know it was my birthday / when…. | Heather Kapplow on SHREW: You cannot tame us. | Chris Spurgeon on ALBATROSS: No such thing as a lesser one. | Charlie Mitchell on JACKALOPE: This is no coney. | Vanessa Berry on PLATYPUS: Leathery bills leading the plunge. | Tom Nealon on PANDA: An icon’s inner carnivore reawakens. | Josh Glenn on FROG: Bumptious ~ Rapscallion ~ Free spirit ~ Palimpsest. | Josh Glenn on MOUSE.

ALSO SEE: John Hilgart (ed.)’s HERMENAUTIC TAROT series | Josh Glenn’s VIRUS VIGILANTE series | & old-school HILOBROW series like BICYCLE KICK | CECI EST UNE PIPE | CHESS MATCH | EGGHEAD | FILE X | HILOBROW COVERS | LATF HIPSTER | HI-LO AMERICANA | PHRENOLOGY | PLUPERFECT PDA | SKRULLICISM.