49th PARALLEL (20)

By:

March 5, 2023

University of Toronto philosopher Mark Kingwell and HILOBROW‘s Josh Glenn are coauthors of The Idler’s Glossary (2008), The Wage Slave’s Glossary (2011), and The Adventurer’s Glossary (2021). While researching and writing their respective sections of the latter book, they engaged in an epistolary exchange about real-world and fictional adventures. (As intended, passages from this exchange appear verbatim in the book.) Via the series 49th PARALLEL, the title of which references not only Mark and Josh’s cross-border collaboration but one of their favorite WWII movies, HILOBROW is pleased to share a lightly edited version of their adventure-oriented exchange with our readers.

49th PARALLEL: FULL OF BEANS | DERRING-DO | ON THE BEAM | A WIZARD DODGE | RURITANIA | ROBINSONADE | CAMARADERIE | WISH I WERE HERE | PICARESQUE | TILTING AT WINDMILLS | PLUCK | SKOOKUM | SAGAMAN | HOT-SHOT | CUT AND RUN | THE WORST ANGELS OF OUR NATURE | ACUMEN | APOPHENIA | ESCAPADE | I AM NOT A NUMBER | HEAD-SHOT CIRCUS | 86 | GAMBIT | PLAY THE GAME | HAYWIRE | REPETITION.

24th August, 2019

TORONTO

Basic as in fundamental or foundational or… profound? I take the point, though; a stronger word is needed there.

Have just ordered a copy of The Riddle of the Sands, did not know it.

Fun fact: I am typing this on a laptop decorated with, among things, one of your green HERMENAUT stickers. (Tintin’s rocket ship, an STP motor oil patch, and the RCAF flag are also featured: space travel, hot rods, and aviation.) I also used to wear one of the old blue-on-blue Hermenaut t-shirts, and the only person who ever understood the term, and smiled in appreciation, was my friend Russell Smith, a novelist and essayist. His fiction is all about erotic (mis)adventure in urban settings, the kind of thing we usually get up to in our twenties or early thirties. Or, as in my case, there may be a new bout of such (mis)adventures after a divorce. In 2002 I was 38 and newly single, living in Manhattan, reasonably wealthy and presentable. There was a post-9/11 recklessness in the air. You can get into a lot of mischief under circumstances like those….

Anyway, those prison-break films, and especially The Prisoner, were extremely compelling to me when I was young. I had not yet read Foucault, but the tension between inside and outside, obvious and yet perhaps finally unreal, offers a threshold function. Papillon (1973) is great on this, Steve McQueen comprehensively reshaped from his peak-cool performances in Bullitt (1968) and The Thomas Crown Affair (also 1968!). This inside-outside logic may work as an avoidance ritual, of course, obscuring the larger disciplinary order by offering effectively staged versions of it, visited dramatically on a minority of the population. Or it may (perhaps later) reveal the falseness of the divide. “I am not a number, I am a free man!” is McGoohan’s defiant cry in The Prisoner, where he is significantly branded, and addressed, as Number Six. But surely that is a motto for everyone, maybe especially those of us not obviously incarcerated in the toy-time “Village” of the series, with its cricket blazers, boating hats, and carnivalesque accouterments. I recall you suggesting that a bunch of us should make a pilgrimage to, maybe even hold a con in, Portmeirion, Wales, where the show was filmed. Bucket list!

Another fun fact: The Prisoner‘s stirring lightning-strike opening sequence, with that unforgettable soundtrack, suggests a back-link to McGoohan’s previous hit TV shows, Secret Agent and Danger Man. As I have suggested before, writing for your excellent website, the real star of all three shows is McGoohan’s forehead.

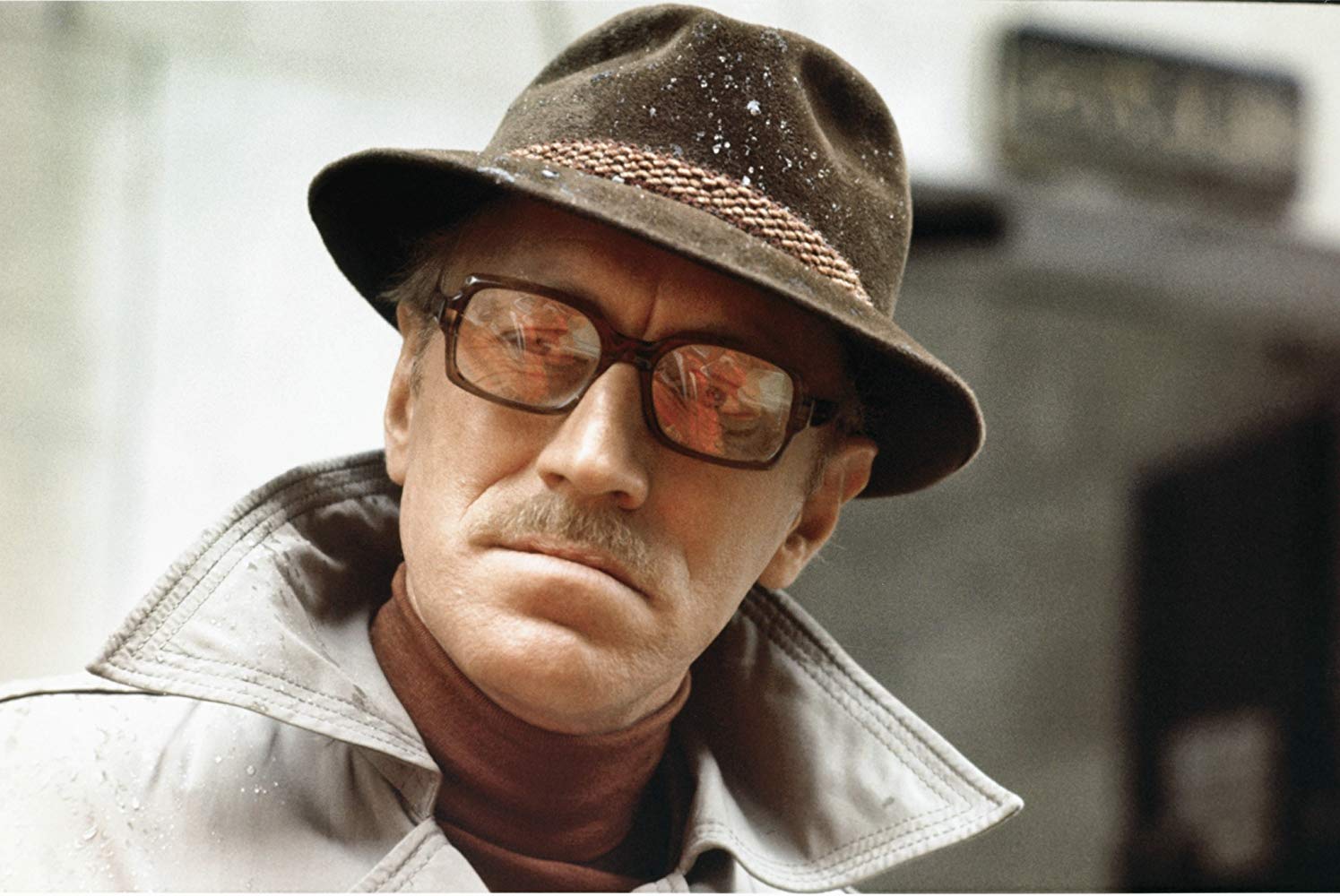

I won’t comment on all of the final categories you offer except to reiterate that we are going to need a map! I do love those cynical, or depressive, stories where the network is eventually revealed, but as unassailable. Three Days of the Condor is a perfect example, and that final scene about the complicity of the press in the whole network of money and power was probably at least as motive for me becoming a political critic as anything I read in college. Faye Dunaway migrates over, seven years more mature and even more beautiful than in her foiled insurance-agent/seductress/spy role in Thomas Crown; and how great is it that Max von Sydow, the knight who played chess with Death in Bergman’s The Seventh Seal (1958), is the main assassin! I loved the idea that the Redford character, with his tweed jacket and blue button-down shirt, had a job just reading for a living.

His midtown-Manhattan backdoor deli-run for lunch orders, exempting him from the hit on the little brownstone CIA outpost, is the equivalent of the Roger Thornhill coincidence of appearing to answer a page for George Kaplan in the Plaza Hotel’s Oak Bar. These minor narrative slippages set the ensuing adventure in motion, bringing the mundane man into contact with The Network. I remember watching Three Days with my mother, and she kept complaining that she couldn’t follow the story, but she sure loved just looking at Mr. Redford anyway, in his high-collared pea coat. So it goes. There are, in passing, some great Holmesian details: Redford’s character, spotting that the postman is not real, is in fact an assassin, because his shoes are the wrong colour. Love that kind of thing — the nature of clues, and how to notice them. Or, as in Nolan’s Memento, have them tattooed on your body!

That movie gives me an opportunity to go back to basics (or fundamentals, or foundations). Personal identity is an adventure, as we noted earlier, with or without a coherent narrative. At least since Locke, two things have been considered crucial: continuity of memory, and continuity of physical presence. Guy Pierce’s character shows us what happens when the first is disrupted, Kafka’s Gregor Samsa demonstrates the breakdown of the second.

I love Kingsley Amis’s take on “The Metamorphosis.” After referencing Dostoevsky and Poe, he avers that Kafka’s tale is the perfect depiction of a severe alcoholic hangover. There is, he says, “a telling touch in the nasty way everyone goes on at the chap.” Distinguishing between the physical hangover and the metaphysical one, Amis notes how hard it is to believe, when hungover, that “You are not sickening for anything, you have not suffered a minor brain lesion, you are not all that bad at your job, your family and friends are not leagued in a conspiracy of barely maintained silence about what a shit you are, you have not come at least to see life as it really is, and there is no use crying over spilt milk.” If you can get over these crippling delusions, you are okay. (I’m one of the lucky ones: I almost never get hangovers.)

I am veering off-topic, so will haul this back to the action/adventure question you raise. It’s sadly true that much of what passes for ‘action’ these days, in film anyway, is lacking in adventure. I also think it is sad, and alas telling, that Lee Child’s boringly formulaic Jack Reacher stories are considered the modern gold standard for adventure fiction. What a comedown from Gavin Lyall, Desmond Bagley (underrated), and Lionel Davidson, not to mention the classic names already in play. Even Donald Hamilton and John D.Macdonald, on the American side of the Atlantic, write FAR SUPERIOR novels, as novels. Plenty of action, but real character and real adventure.

Right next to me as I write this is a novel by someone called Nick Petrie, which features his ex-Marine hero Peter Ash. Petrie is considered the heir to Lee Child, but all that means is more formulaic bullshit, and those incredibly annoying one sentence paragraphs.

Used to end every dramatic section.

As if that conveys tension.

Because it is staccato.

Like jumbled thoughts.

Or gunshots.

Implying drama without creating it.

A very annoying tic.

In sub-par fiction.

By bad writers.

Basta! In movies, we can readily see the quality difference between real action sequences, sometimes on actually dangerous locations, and the CGI and quick-cut norms that have come to dominate the genre. Younger viewers complain about the slow pace of older movies, but pace is essential to adventure! Hyperkinesis is not the same thing as tension. It’s cheap, and gaudy, and aesthetically meretricious. But I’m old school, I guess.

Final thought, about Kafka again: The Trial is the very model of a metaphysical/spiritual adventure precisely because it involves a quest with no clear goal, a network with no obvious hierarchy, and a violent ending that is (to me, anyway) bleakly funny. In my fiction and philosophy class — which I think you would indeed love — I give the students a little essay by David Foster Wallace, in which he talks about how hard it is to convey the peculiar brand of Kafkaesque funny, and its constant deployment of thresholds. We should imagine, he says, an increasingly frenetic prisoner in a room, pushing and pushing and pushing on the only door, desperate to get out. He rages and rants, sweats and weeps. Then it is revealed that the door opens inward, not outward. Das ist komisch, DFW concludes. Oh yes.

But even if we solve this little puzzle, another, harder one awaits us. Is the existential opening an escape hatch, or just a sly trap-door? We’ll never know unless we try it.

Mark

ALSO SEE: Josh’s BEST 250 ADVENTURES of the 20th CENTURY list, and the A IS FOR ADVENTURE series | Mark on PATRICK McGOOHAN, BATTLESTAR GALACTICA, THE MAN FROM U.N.C.L.E., THE EIGER SANCTION, and THE HONG KONG CAVALIERS.