OFF-TOPIC (48)

By:

February 27, 2023

Off-Topic brings you over-the-transom, on-tangent essays, dialogues and subjective scholarship on an occasional, impulsive basis. As this Black History Month closes, a discussion of new narratives in popular Black storytelling that can keep opening back up…

Heroes’ natural habitat is retrospect. Whether or not they actually lived in the first place, nothing transubstantiates the frail mortal body like a voluminous body of work. More will be written about some people through time than ever was during their life, which is often more than they ever write about themselves (at least, long-form and pre-internet) — and over the course of history, what’s imprinted is the legend.

Sometimes you can just start with the legend. By the time I came across an older sibling’s abandoned copy of Silver Surfer #5 (1969), all my family’s heroes were stories — King, the Kennedys, FDR — and we tended to think of God as the longest and most made-up story of all.

That didn’t mean there was no need to invent him. For those days, I do mean “him,” but mass culture, and counterculture, tended to favor feminine or maternal male deities. Mine was the Silver Surfer, a kind of cosmic angel cast from the heavens of space to the hell of our unthinking Earth. Sent here to sacrifice our planet to the hungers of his lifeforce-eating master Galactus, the Surfer instead sacrificed his own freedom to protect us, repelling his master but bound to the Earth by an energy barrier Galactus put up around the planet as a parting punishment.

I grew up reminded that we’d all recently been expelled from the paradise that was the 1960s’ sense of possibility; MLK and many others had just yesterday sacrificed themselves for a promised land those they looked out for would reach. The Surfer (one letter from “suffer”) would take on our lament about this, spending every issue bemoaning human viciousness and trying to find a way back home. Slight and androgynous like Jesus, glowing like Moses did after he’d looked upon God, he was a literal reflection of us (and sometimes a cathartic projection, when the masculine side would kick in for him to beat down some bigots or bullies, as pop culture’s other peaceful souls pushed too far — Billy Jack, Kwai Chang Caine — seemed driven to do all the time).

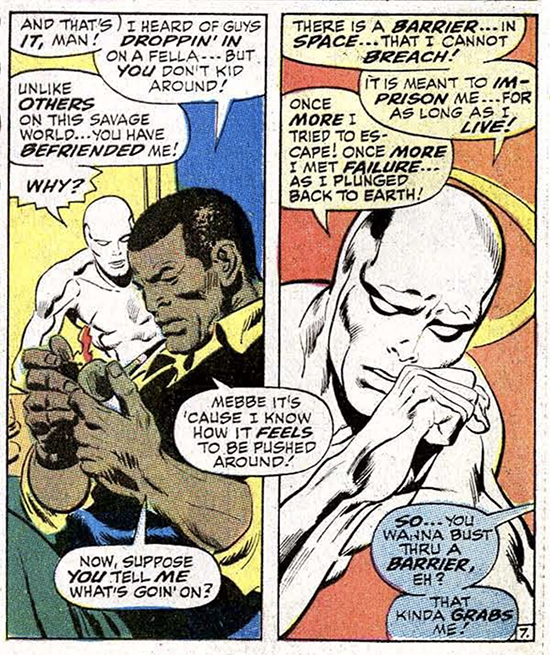

But even in the story, those of us who weren’t metaphors were still mortal. Which is where the Martin Luther Kings come in, and where Al B. Harper came and went. In issue #5, the Surfer again falls to Earth after some barrier-breaking technology fails him, and is taken in by Harper, a reclusive physicist. True to the era’s unsung Black STEM trailblazers, Al lives alone and relates to the Surfer’s isolation. Intrigued by the problem, he agrees to help. Their efforts put the Surfer in position when another trampling cosmic dad, The Stranger, arrives in our orbit to wipe the world clean of the moral contagion he feels the human race is. The Surfer tries repelling the Stranger while Al goes searching for the “null-life bomb” the Stranger has planted. He succeeds in defusing it at the cost of his own life, which convinces the Stranger to believe he misjudged us and leave, and leads the Surfer to abandon his own escape and set an eternal flame at Al’s unmarked grave, sailing off as the only being who remembers the story’s real hero.

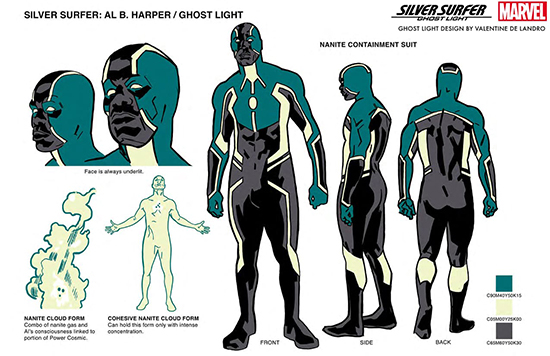

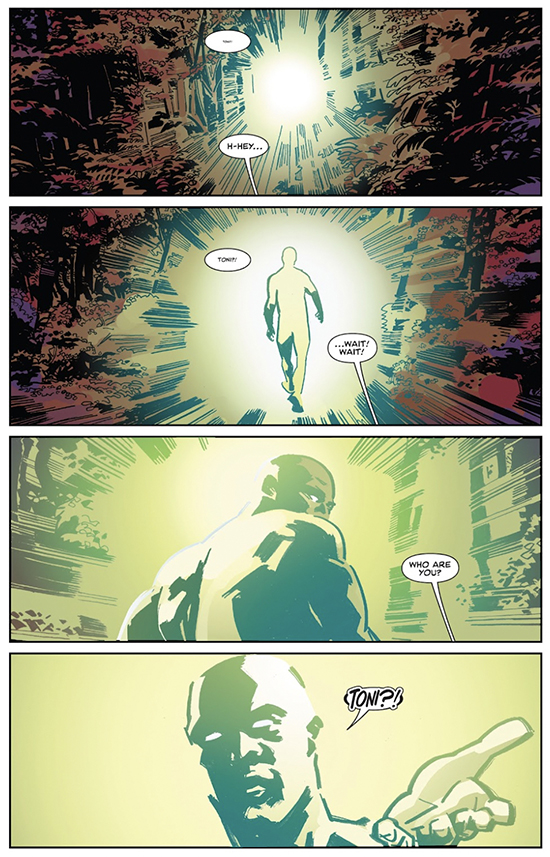

He wasn’t the only one really. Generations of geeks and blerds who read the Surfer’s low-selling, groundbreaking first series have carried the memory of Al Harper as vividly as if he were a multiplex franchise. One of them was multi-award-winning artist, author, critic, essayist and leading Afrofuturist thinker John Jennings (himself a recurring star of this column). In his Marvel Comics debut, Jennings has teamed with artist Valentine De Landro to tell the story of Al Harper’s life — and afterlife, in the miniseries Silver Surfer: Ghost Light. Having been haunted by his memory, Jennings breathes new life into the character, both elevating him into a mystic-sci-fi pantheon and drawing out the flesh-and-blood person we knew all too briefly and too little about. De Landro is the perfect collaborator to articulate the otherworldly sensibility, his cosmic darknesses and eerie illuminations bringing elements of shadow and sorcery to the gleam and grandeur of the Surfer’s high-tech epic world. We meet a transformed Al, mysterious mad scientists, mythic-future monsters, and Al’s niece and nephew, Toni and Josh, who Jennings told me he “wanted to be about the age I was when I first read this story.” That was a fitting mission statement for a conversation about how to finally continue the beginning…

HILOBROW: “Ghost Light” is a well-chosen name, since I get a strong sense of the scientific supernatural from both the mix of genres and frames of reference here, and from Valentine’s visuals. Were you both going for a kind of sci-folklore feel? We are seeing a story of cosmic beings in a shadowy forest!

JENNINGS: The idea to resurrect Al Harper came from my researching another Marvel book project. This one is a co-published non-fiction book with Simon and Schuster. I am co-authoring the book with Angelique Roché. The project is called My Super Hero is Black and it is a rough guide to Marvel’s Black characters from the 1950s to current day. I was doing a lot of re-reading of older Marvel books during the George Floyd protests. It seemed like every day there was another Black citizen killed by the police. Also, COVID was killing marginalized communities in larger numbers. There was a lot of Black Death in the world. I came across Al’s story and it just seemed Stan Lee had written a “Black Death Matters” story to me. This story was written only a year after the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. and there was still a lot of racial unrest in the U.S. It seemed to me that Al needed to come back and Marvel agreed.

Also during this time of tumult, COVID had forced so many performance theaters to close; either temporarily or permanently. There’s a theatre folk tale/superstition that every stage has a ghost or a phantom. So, the custom is to leave on a light for them after the night of shows is done. This light is called a “ghost light.” It also means that the show will come back soon. During COVID there were hundreds of ghost lights on. I just thought it would be a great name for a character who was being resurrected.

And yes, it also has this merging of the scientific with the spiritual. Al Harper is a genius-level intellect and he gets the Power Cosmic! I think of the Power Cosmic as “space magic.” I always loved the connections between Dr. Strange and the Silver Surfer so, it makes sense to me that our “haunted house” story has some of those overtones.

HILOBROW: Dwayne McDuffie classically said of his childhood comic-fan cohort, “As far as we were concerned, Sub-Mariner was Black.” And in his memoir Brent Staples speaks of identifying more in his youth with cosmic characters like the Silver Surfer, for their sense of solitude and exclusion, than with the few actually Black comicbook characters in the 1960s who conveyed more cultural surface than experienced essence. Though right there amid the Surfer’s best stories was this one-shot Black character who hinted at more than the superficial stereotypes of the time. Do you feel there’s still some validity for that kind of displaced symbolism of being “other,” or is Ghost Light the story that was meant to grow 50+ years ago?

JENNINGS: I think a lot about the characters that we “project” Blackness onto. Because of the ideas around being displaced, outcast, or persecuted, those characters feel like they have a sense of race on them that others don’t. I definitely feel that the Surfer has that feel to him, I’ve found that a lot of Black men relate to him on a very personal level. Other characters like that are the Beast, Nightcrawler, Cyclops, the Hulk and even Daredevil. This “otherness” manifests itself either in the characters’ lives or reified in their bodies in some way.

HILOBROW: Both the titular heroes are shrouded in mystery and barely introduced in the first issue, yet they are both a palpable presence, and the buildup of suspense is expert. Is there an importance to what’s not seen?

JENNINGS: Yes. I think that “writing from the gutter” is important in comics. That is, writing from the spaces in-between the panels. In every comic there’s a multitude of stories that are unseen because only the images in the panels actually matter. That’s a very interesting commentary on what Blackness feels like. I even think of the gutter as The Veil in a very Du Boisian sense. W.E.B. Du Bois said that Black people live from within “The Veil.” It’s almost like a marginalized alternate universe. The Veil has different rules and is unseen by the powers that be. Al has been in The Veil for 54 years. Now he finally has a place in the panels. This story’s first chapter is really all about answering Stan Lee’s query “And Who Shall Mourn for Him?” [the title of Al’s original appearance]. I wanted to deal with the response to that call, so to speak. Al was never meant to survive. So, what does that mean to his loved ones? That’s a huge part of what I wanted to discuss. Al gets the Power Cosmic but he also becomes a fully fleshed-out human being.

HILOBROW: In this book there’s also an important role played by what’s seen but not said. I’m thinking in particular of that one remarkable silent page where the Surfer is approaching Earth, but we only know it through this soundless sequence of streaking starlight and increasingly blurry atmosphere and terrain, presumably from the Surfer’s POV, vibrating like the second before reality itself rattles apart. How did you collaborate on staging such scenes, giving us all we need to know while also keeping us in a state of anxious mystery?

JENNINGS: It was easy for me. I just wrote an action and Valentine takes that and makes it better!! That was an amazing combination of Valentine’s “cinematography” based on my script and Matt Milla’s coloring on that scene. I was blown away by it.

HILOBROW: How did you calibrate the sense of “comicbook time” in structuring this story? The Surfer is something of a counterculture saint and Al Harper was resolutely a survivor of the segregation era, yet some bending of spacetime is necessary to put their relationship anywhere near the present day. Was it kind of a mindset of “the more things change, the longer they take to really change”?

JENNINGS: So, my first pitch didn’t take that into account. Josh and Toni were Al’s great-nephew and -niece in my first ideas. [Marvel editor] Tom Brevoort told me quickly that wasn’t going to wash because of “Marvel Time.” The Marvel Universe starts with The Fantastic Four and that start is always ten years ago. I had to re-think birthdays and ages immediately. So, our Al wouldn’t have experienced the exact type of racial oppression as before. However, I managed to sneak those issues into the story in a subtle manner. Systemic issues around race and oppression are part of the story but not at the forefront. I wanted to focus on Black Joy and the power of creativity, family and the resilience of Black people in the face of great adversity.

The reason I pitched this story is mostly because I felt that if I saved this Black man from obscurity and death, even though he isn’t real, that it would inspire others in real life to consider a broader scope of empathy and humanity.

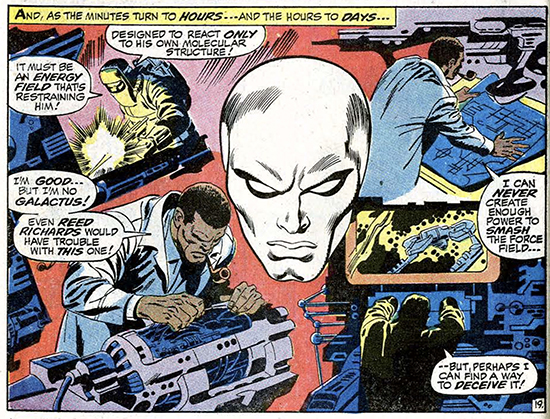

HILOBROW: There are looks that seem to embody an era — literally when we’re talking about character design. The Surfer’s sleek sheen was the epitome of midcentury chrome-plated purity, an industrial sublime; and Ghost Light’s design looks like a mix of computer-generated aerodynamic paneling and ritual markings, more skin than clothing, reflecting that feeling in current athletic wear that we’re moving beyond human, or seeming like some digital divinity that redefines our conception of the spiritual. What were you seeking to say with his appearance?

JENNINGS: Valentine totally riffed off of my initial designs so well. You can see some of my original notions and he just made them much more elegant and efficient. He also kept my ideas around how Ghost Light embodies “sankofa” in the suit. The oval on his chest represents the egg in the Akan people’s “sankofa” symbol. The main symbol is one of a bird reaching back over its back to take an egg from the past and put it into the future. The term “sankofa” means “go back and get it.” It’s a central theme in most Afrofuturist works and Ghost Light is definitely highly inspired by Afrofuturism!

[Images (top to bottom): Taurin Clarke’s cover to Ghost Light #1; two images from 1969, words by Stan Lee, art by John & Sal Buscema; De Landro’s model-sheet for Ghost Light; three excerpts from Ghost Light #1, words by Jennings, art by De Landro; one of Jennings’ original concept designs for Ghost Light]

MORE POSTS by ADAM McGOVERN: OFF-TOPIC (2019–2024 monthly) | textshow (2018 quarterly) | PANEL ZERO (comics-related Q&As, 2018 monthly) | THIS: (2016–2017 weekly) | PEOPLE YOU MEET IN HELL, a 5-part series about characters in McGovern’s and Paolo Leandri’s comic Nightworld | Two IDORU JONES comics by McGovern and Paolo Leandri | BOWIEOLOGY: Celebrating 50 years of Bowie | ODD ABSURDUM: How Felix invented the 21st century self | KOJAK YOUR ENTHUSIASM: FAWLTY TOWERS | KICK YOUR ENTHUSIASM: JACKIE McGEE | NERD YOUR ENTHUSIASM: JOAN SEMMEL | SWERVE YOUR ENTHUSIASM: INTRO and THE LEON SUITES | FIVE-O YOUR ENTHUSIASM: JULIA | FERB YOUR ENTHUSIASM: KIMBA THE WHITE LION | CARBONA YOUR ENTHUSIASM: WASHINGTON BULLETS | KLAATU YOU: SILENT RUNNING | CONVOY YOUR ENTHUSIASM: QUINTET | TUBE YOUR ENTHUSIASM: HIGHWAY PATROL | #SQUADGOALS: KAMANDI’S FAMILY | QUIRK YOUR ENTHUSIASM: LUCKY NUMBER | CROM YOUR ENTHUSIASM: JIREL OF JOIRY | KERN YOUR ENTHUSIASM: Data 70 | HERC YOUR ENTHUSIASM: “Freedom” | KIRK YOUR ENTHUSIASM: Captain Camelot | KIRB YOUR ENTHUSIASM: Full Fathom Five | A 5-part series on Jack Kirby’s Fourth World mythos | Reviews of Annie Nocenti’s comics Katana, Catwoman, Klarion, and Green Arrow | The curated series FANCHILD | To see all of Adam’s posts, including HiLo Hero items on Lilli Carré, Judy Garland, Wally Wood, and others: CLICK HERE