RADIUM AGE: 1934

By:

December 10, 2022

A series of notes towards a comprehensive account of the science fiction genre’s Radium Age (1900–1935). These notes are very rough-and-ready, and not properly attributed in many cases. More information on Josh’s ongoing efforts here and here.

RADIUM AGE TIMELINE: [1900 | 1901 | 1902 | 1903] | 1904 | 1905 | 1906 | 1907 | 1908 | 1909 | 1910 | 1911 | 1912 | 1913 | 1914 | 1915 | 1916 | 1917 | 1918 | 1919 | 1920 | 1921 | 1922 | 1923 | 1924 | 1925 | 1926 | 1927 | 1928 | 1929 | 1930 | 1931 | 1932 | 1933 | [1934 | 1935]. (The brackets, here, indicate “interregnum” years — i.e., periods of overlap between sf’s Radium Age and its Scientific Romance and so-called Golden Age eras.)

The year 1934, in my periodization scheme, marks the beginning of the cultural decade known as the “Thirties.” Of course there are no hard stops and starts in culture, so it’s more accurate to describe 1934 (and 1933) as cusp years during which the Twenties end and the Thirties begin.

In my original formulation of the Radium Age, this era in the development of the sf genre ended in 1933. However, as noted above, eras don’t simply begin or end on a particular date… it’s a process. So I’ve extended my purview into the years 1934 and 1935 as well, seeking traces of the vanishing Radium Age even as sf’s so-called Golden Age begins to emerge.

It’s worth noting Asimov’s Before the Golden Age collection (1974) republishes stories that originally appeared from 1931 through 1938. So in Asimov’s POV, the Golden Age gets started at some point in here, or perhaps not even until 1939 — it’s a moving target.

The month after Tremaine announced his “thought variant” policy at Astounding (see 1933), Charles Hornig, a 17-year-old sf fan whom Gernsback had hired to replace Lasser at Wonder Stories, launched his own “New Policy”; as with thought variants, the goal was to emphasize originality and bar stories that merely reworked well-worn ideas. Hornig’s rates were lower than Astounding‘s, and sometimes his writers were paid very late, or not at all; but Hornig managed to find some good material, including Stanley G. Weinbaum’s “A Martian Odyssey”, which appeared in the July 1934 Wonder and has been frequently reprinted.

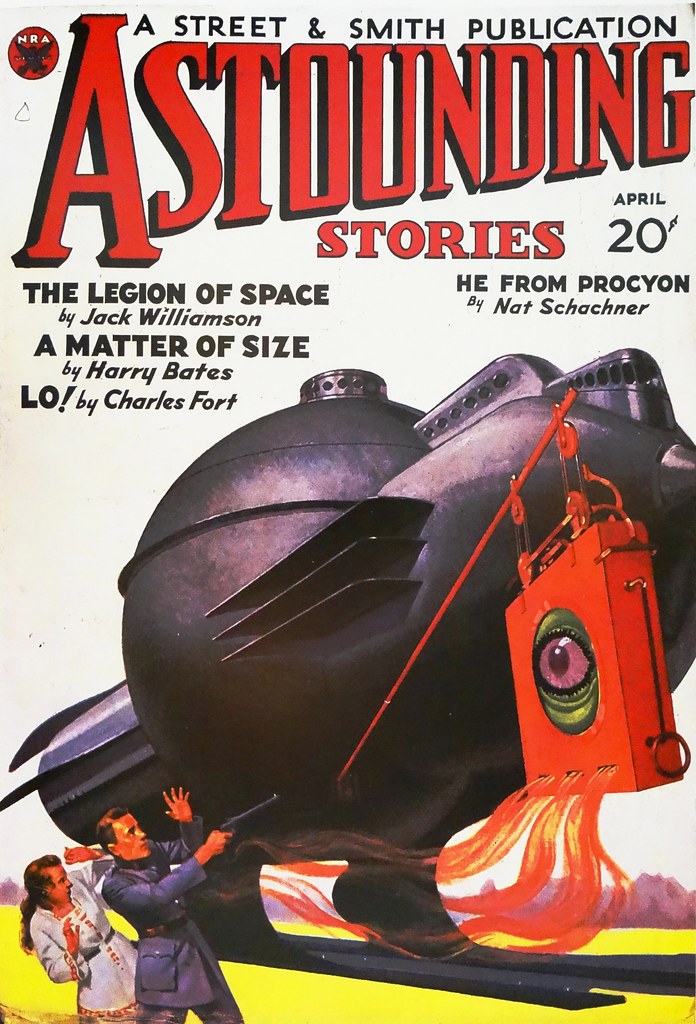

The April 1934 issue of Astounding under Tremaine is one of the most memorable from the period, according to Ashley’s Time Machines. It features the first installment of Williamson’s “The Legion of Space,” and begins serialization of Charles Fort’s Lo! (1931).

Gernsback experimented with some companion fiction titles in other genres in 1934, but was unsuccessful, and Wonder Stories‘ decline proved irreversible. After a failed attempt to persuade his readers to support a subscription-only model, he gave up and sold the magazine to Standard Magazines in February 1936. It was retitled Thrilling Wonder Stories and given to Mort Weisinger to edit. The format was left unchanged, but the stories and covers became much more action-oriented.

At their peak of popularity in the 1920s–1940s, the most successful pulps sold up to one million copies per issue. In 1934, Frank Gruber said there were some 150 pulp titles. During the Second World War paper shortages had a serious impact on pulp production, starting a steady rise in costs and the decline of the pulps. Beginning with Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine in 1941, pulp magazines began to switch to digest size; smaller, thicker magazines. In 1949, Street & Smith would close most of their pulp magazines in order to move upmarket and produce slicks.

Competition from comic-books and paperback novels further eroded the pulps’ marketshare, but it was the widespread expansion of television that sounded the death knell of the pulps. Also, in a more affluent post-war America, the price gap compared to slick magazines was far less significant than it had been during the Depression. In the 1950s, men’s adventure magazines began to replace the pulp. (The 1957 liquidation of the American News Company, then the primary distributor of pulp magazines, has sometimes been taken as marking the end of the “pulp era”; by that date, many of the famous pulps of the previous generation, including Black Mask, The Shadow, Doc Savage, and Weird Tales, were defunct.)

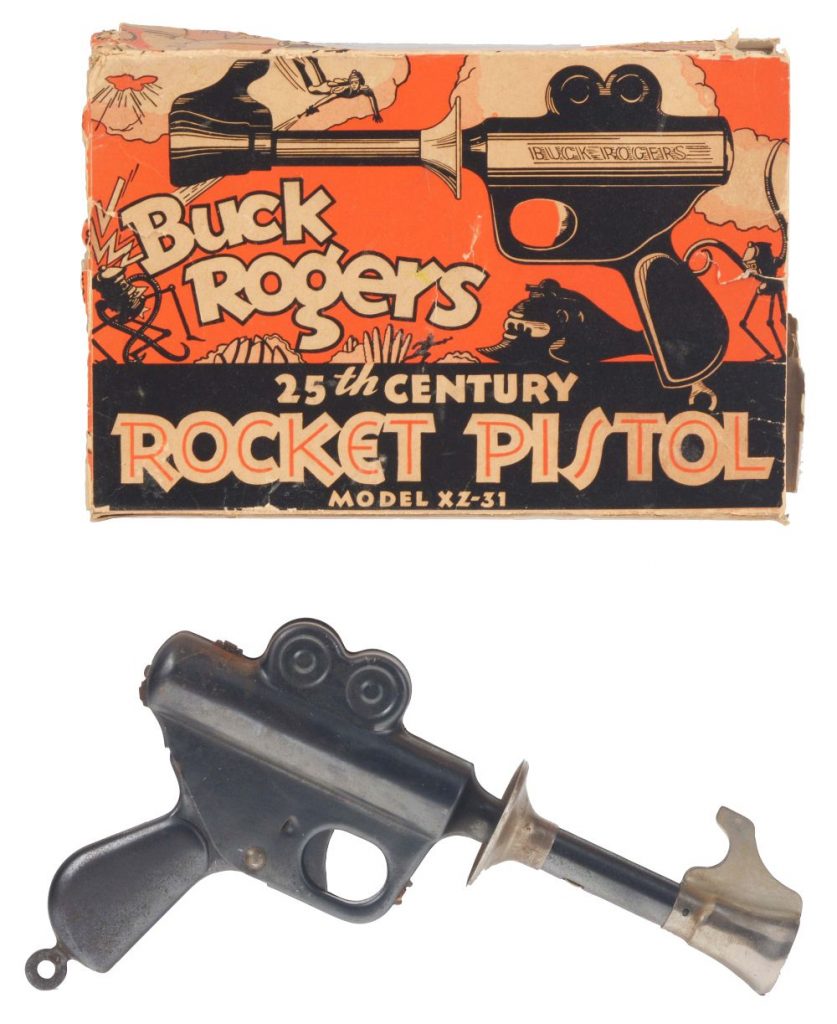

Speaking of comic books, Famous Funnies, an American comic strip anthology series considered by pop culture historians as the first true American comic book, began publishing in 1934. Issue #3 began a run of Buck Rogers features (see 1929). Buck Rogers would eventually run in issues #3–190 and 209–215.

Copyrighted works from 1934 will enter US public domain on January 1, 2030. They will become free for all to copy, share, and build upon.

Proto-sf coinages dating to 1934, according to the Historical Dictionary of Science Fiction: AIRCAB | ANTIMATTER | BUCK ROGERS (= science fictional adj.; (specif.) characteristic of hackneyed or dated science fiction) | COMMUNICATOR | CREDIT (a unit of currency) | FANGIRL | FLAME GUN | HYPERSPATIAL | LUNA CITY | MUTANT (N. Schachner’s “100th Generation” in Astounding Stories) | OUTWORLDER | THOUGHT-CONTROLLED | TIME FAULT | ZAP GUN (name of a Buck Rogers tie-in toy)

PS: Simone Caroti’s The Generation Starship in Science Fiction: A Critical History, 1934-2001 (2011) dates the generation starship concept to 1934.

- E.E. “Doc” Smith’s Triplanetary (serialized 1934, in Amazing Stories; as a book, 1948). As two super-races battle for control of the universe, a backward planet in a remote galaxy has become their battleground. One race, the Eddorians, influences Earthlings to fail; but the Arisians influence Earthlings to transcend their limitations. (The battle has been going on for millennia: for example, it led to the sinking of Atlantis. Jack Kirby’s epic concept — in The Eternals — about the genetic experimentations of the alien Celestials, using Earth as a laboratory — owes a large debt to Smith.) After World War III, the Arisian influence begins to predominate; humankind explores space, and forms a Triplanetary League: Venus, Earth, and Mars. Against this cosmic backdrop, we follow the adventures of secret agent Conway Costigan and the beautiful and heroic Clio Marsden, who are captured by amphibian aliens — an advance patrol looking to harvest Earth’s iron ore. We also learn that the Arisians have been supervising two bloodlines, culminating in the superheroic Kim Kinninson and Clarissa MacDougall; their children, we’ll discover in Smith’s Lensman series, become humankind’s protectors. Moskowitz in Seekers of Tomorrow says here Smith’s writing had improved even beyond Spacehounds of IPC (1931). Fun fact: After the original four novels of the Lensman series (Galactic Patrol, Gray Lensman, Second Stage Lensmen, Children of the Lens) were published (1937–1948), Smith expanded and reworked Triplanetary to make it part of the Galactic Patrol series, interpolating the prime mover influence, which detracts from the original’s zest. While writing these books, Smith worked full-time as a food scientist — for a doughnut company.

- Jack Williamson’s The Legion of Space (April-September 1934 Astounding; in book form, 1947). Building on the space opera conventions established by E.E. “Doc” Smith, Williamson gives us more of the same pulp fare — with less sense of brute scale but with better characterizations. Depicts the far-flung adventures of four buccaneering soldiers. His protagonist, Giles “The Ghost” Habibula, is a former master criminal (of mixed English/Arabic descent, one presumes) who joins with two other outer-space adventurers, Jay Kala and Hal Samdu, to battle the Medusae, a Cthulhu-esque alien race which aims to destroy humankind and inhabit our solar system. Habibula, Kala, and Samdu are members of a military/police force who’ve maintained order and peace among the solar system’s inhabited planets ever since the downfall of the tyrannical Purple Hall empire. However, the Medusae have joined forces with Purple Hall pretenders seeking a return to power. Fortunately, one of the Purples, John Ulnar, switches sides — and becomes a D’Artagnan to Habibula, Kala, and Samdu. Space opera was old news at this point, but Ashley’s Time Machines notes that this story was rousing space opera that was also controlled and humanized; it paved the way for everything from the Green Lantern Corps to Iain M. Banks’s Culture. Habibula became a frequently used model for later sf life-loving grotesques, including Poul Anderson’s Nicholas van Rijn. Fun fact: The series initially comprised The Legion of Space (April-September 1934 Astounding; rev 1947) and The Cometeers (serialized 1936). ALso One Against the Legion (serialized 1939), and The Queen of the Legion (1983, a very late and significantly less energetic addendum).

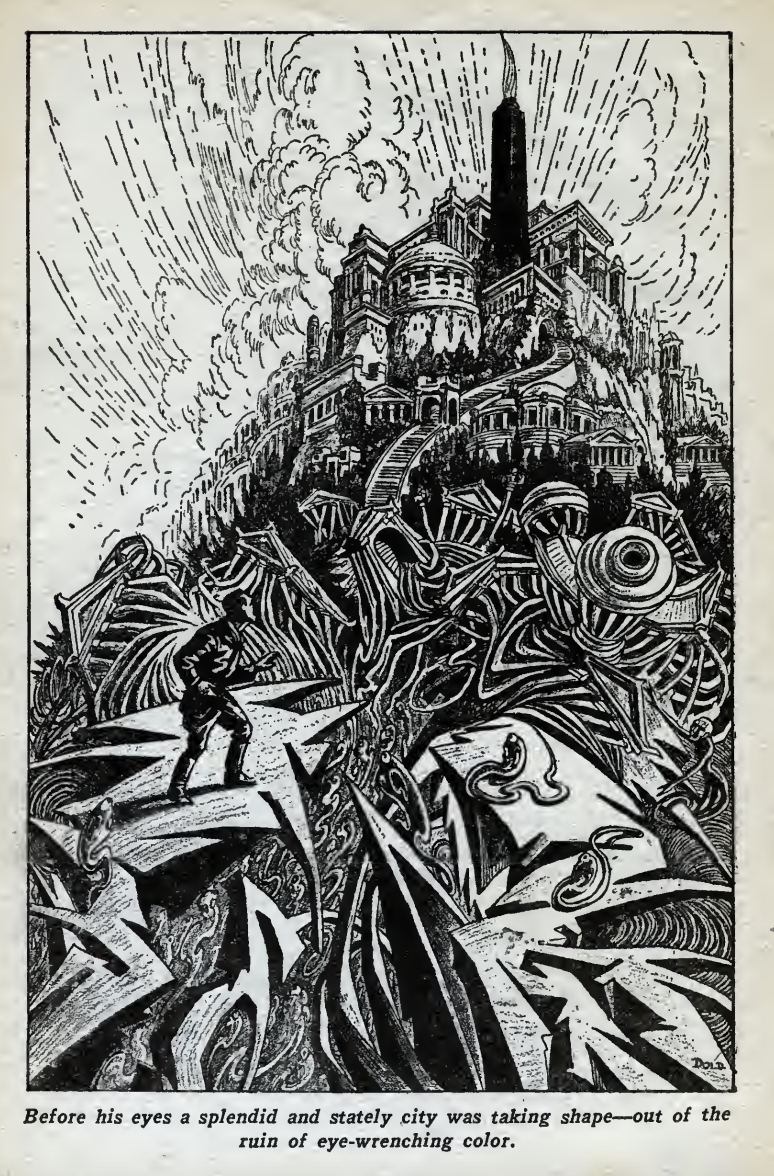

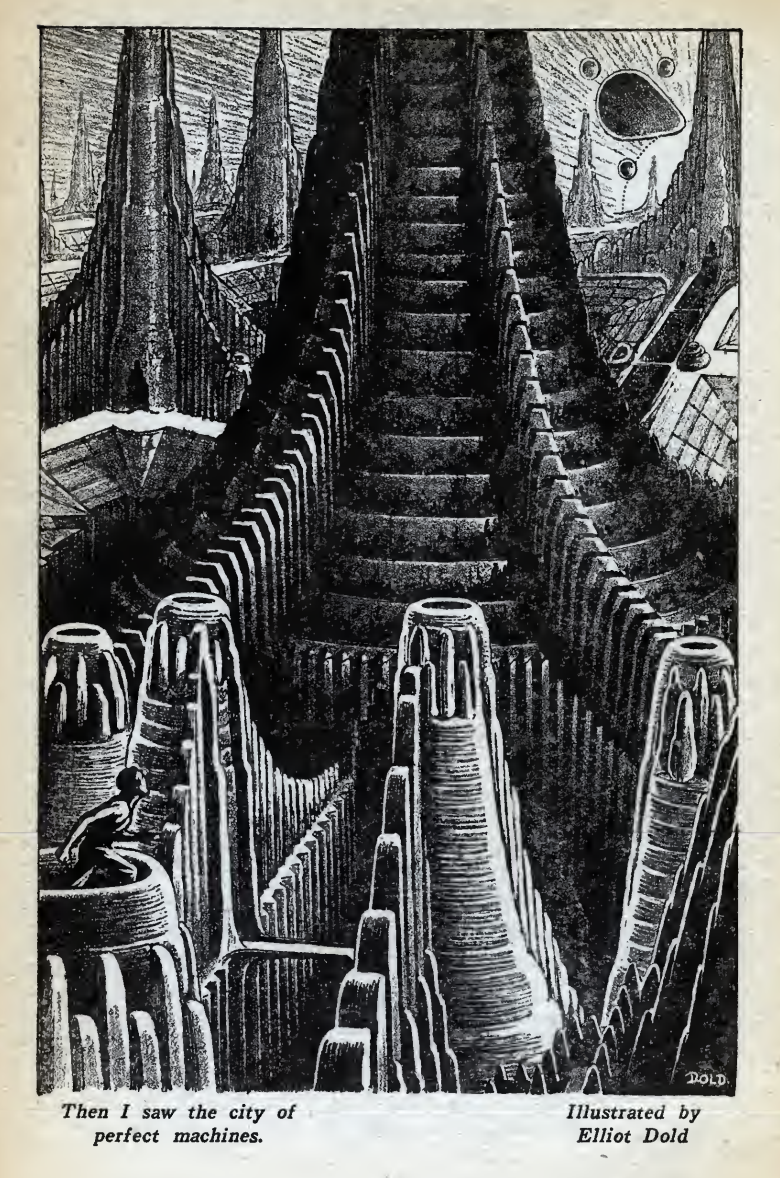

- John W. Campbell (as Don A. Stuart)’s “Twilight” (November issue of Astounding). Campbell wearied of the super-science, action-driven style, and used a slant on his wife’s maiden name to create the Don A. Stuart pseudonym to try something different. “Twilight” was a Thought Variant story — the sort of thing that Tremaine and his readers were looking for. It’s a post-apocalyptic story apparently inspired by H.G. Wells’s “The Man of the Year Million” (an 1893 satire on far-future forecasting, in which people develop tiny bodies and huge heads). Jim Bendell, a real estate agent, recounts his experience with a strange hitch-hiker, Ares Sen Kenlin, who claims to be a scientist, a human hybrid, and time traveler born in the year 3059. He tells Bendell that the people of Earth eventually colonize the Solar System, human existence is virtually free of difficulty, all illness and predators have been eliminated. He test-flew himself 7 million years into the future only to find a dying sun, a cold Earth and a dwindling, incurious race of “little misshapen men with huge heads.” While the heads might contain large brains, they didn’t accomplish much thinking. That’s because the unstoppable, self-repairing machines that presided over their mostly deserted cities did all the thinking for them. Humans, though highly intelligent, have lost their curiosity and drive. There is mention of AI: A group of highly intelligent machines capable of independent thought are humankind’s likely successors. Ashley’s Time Machines claims that this story was the most important in Astounding of the era: “This was a new Campbell, toning down the super-science.” Fun fact: In 1970, “Twilight” was selected as one of the best sf short stories published before the creation of the Nebula Awards by the Science Fiction Writers of America; it was published in The Science Fiction Hall of Fame Volume One, 1929-1964. (Only two stories from before 1935 appear in the volume; the other is Weinbaum’s “A Martian Odyssey.”) Listed in the Science Fiction After 1900 timeline. “‘Twilight’ conveys a mood. It is probably Campbell’s best story, with many implications beyond the story level” — Bleiler. Scott Bradfield calls this one of Campbell’s breakthrough stories “that testify to a young author’s sense of isolation and helplessness in the face of immeasurable universal forces.”

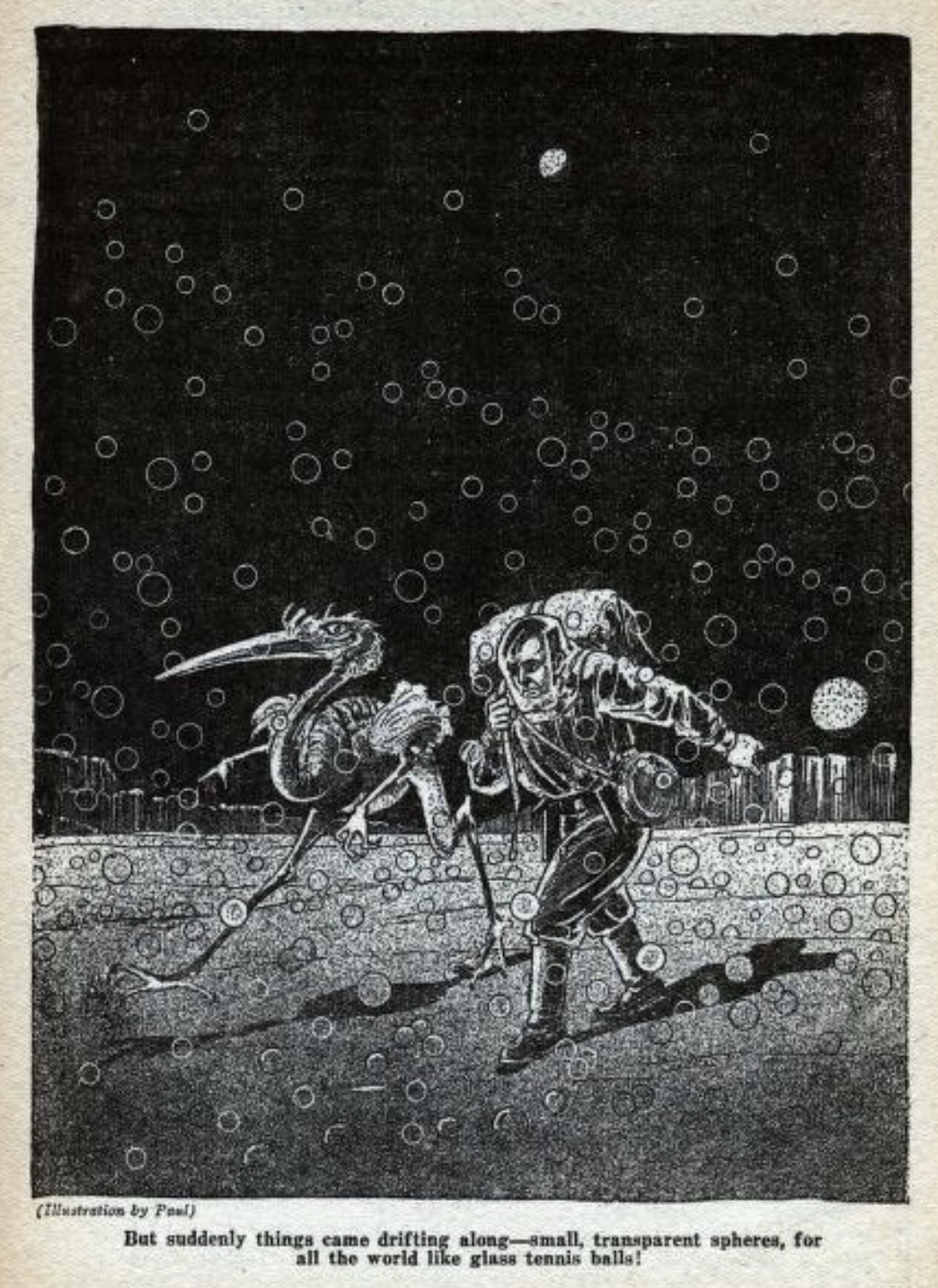

- Stanley G. Weinbaum’s “A Martian Odyssey” (July 1934 issue of Wonder Stories). This was Weinbaum’s second published story and remains his best known. Weinbaum wrote sf for a mere 18 months before his early death. Here he gives is the Martian “Tweel,” widely regarded as the original and now prototypical friendly alien. The story broke new ground in attempting to envisage life on other worlds in terms of strange and complex ecosystems with weird alien lifeforms (though it’s hardly the first to do so); there is a first contact encounter. Told in Weinbaum’s fluent style, it became immediately and permanently popular, having been reprinted dozens of times, and ranking behind only Isaac Asimov’s “Nightfall” (1941) as a favorite example of early genre-SF short fiction. It was followed by a less successful sequel, “Valley of Dreams” (November 1934 Wonder Stories). Ashley’s Time Machines says “A Martian Odyssey” has rightly gone down as “one of the first modern sf stories.” Fun facts: In 1970, it was selected as one of the best science fiction short stories published before the creation of the Nebula Awards by the Science Fiction Writers of America. As such, it was published in The Science Fiction Hall of Fame Volume One, 1929-1964 (ed. Robert Silverberg); it is the earliest story in the collection — apparently nothing from before this year was deserving of inclusion. (Only two stories from before 1935 appear in the volume; the other is Campbell’s “Twilight.”) Also check out Science Fiction: The Science Fiction Research Association Anthology (1988, ed. Martin H. Greenberg, Patricia S. Warrick, Charles G. Waugh), which jumps all the way from a 1904 Wells story to this one — nothing in between! See writeup in John Cheng, Astounding Wonder.

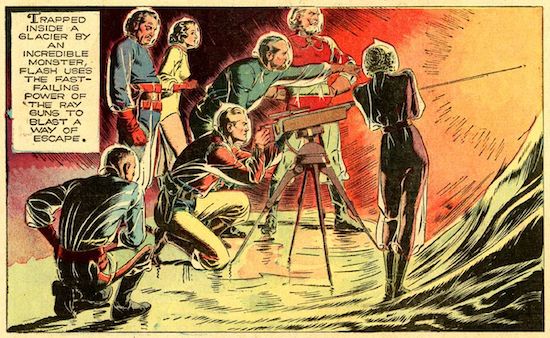

- Alex Raymond’s comic strip Flash Gordon (1934–1943). When Earth is threatened by a collision with the rogue planet Mongo, the brilliant, half-mad Dr. Zarkov builds a rocket ship, kidnaps polo player Flash Gordon and the beautiful Dale Arden, and heads out into space. The backstory of this popular Sunday newspaper strip was lifted from the 1932 sci-fi novel When Worlds Collide; everything else — the adventures of Flash and Dale among the various kingdoms (forest, jungle, undersea, ice, flying) and humanoid species of Mongo, warlord Ming the Merciless’s obsession with Dale and his daughter Princess Aura’s infatuation with Flash, and various tyrants and fascists, is pure pulp. What sets Flash Gordon apart is Raymond’s rich, sensual, dimensionalized artwork — inspired by magazine illustration. Raymond stopped using speech balloons, reduced the number of panels in each strip while increasing their size, worked from models striking heroic and romantic poses, and indulged in elaborate shading… he was the Howard Pyle or N.C. Wyeth of newspaper cartooning. Jack Kirby, Russ Manning, and others were fans; the look of costumed heroes to follow, including Batman and Superman, were directly inspired by Flash Gordon. Raymond’s work, on this strip and the spy adventure Secret Agent X-9, remains a pleasure to peruse. Fun facts: Flash Gordon was featured in three serial films starring Buster Crabbe: Flash Gordon (1936), Flash Gordon’s Trip to Mars (1938), and Flash Gordon Conquers the Universe (1940); it wasn’t until George Lucas failed to acquire the movie rights to the character (from Dino De Laurentiis) that he created Star Wars instead. The 1980 Flash Gordon movie is silly fun.

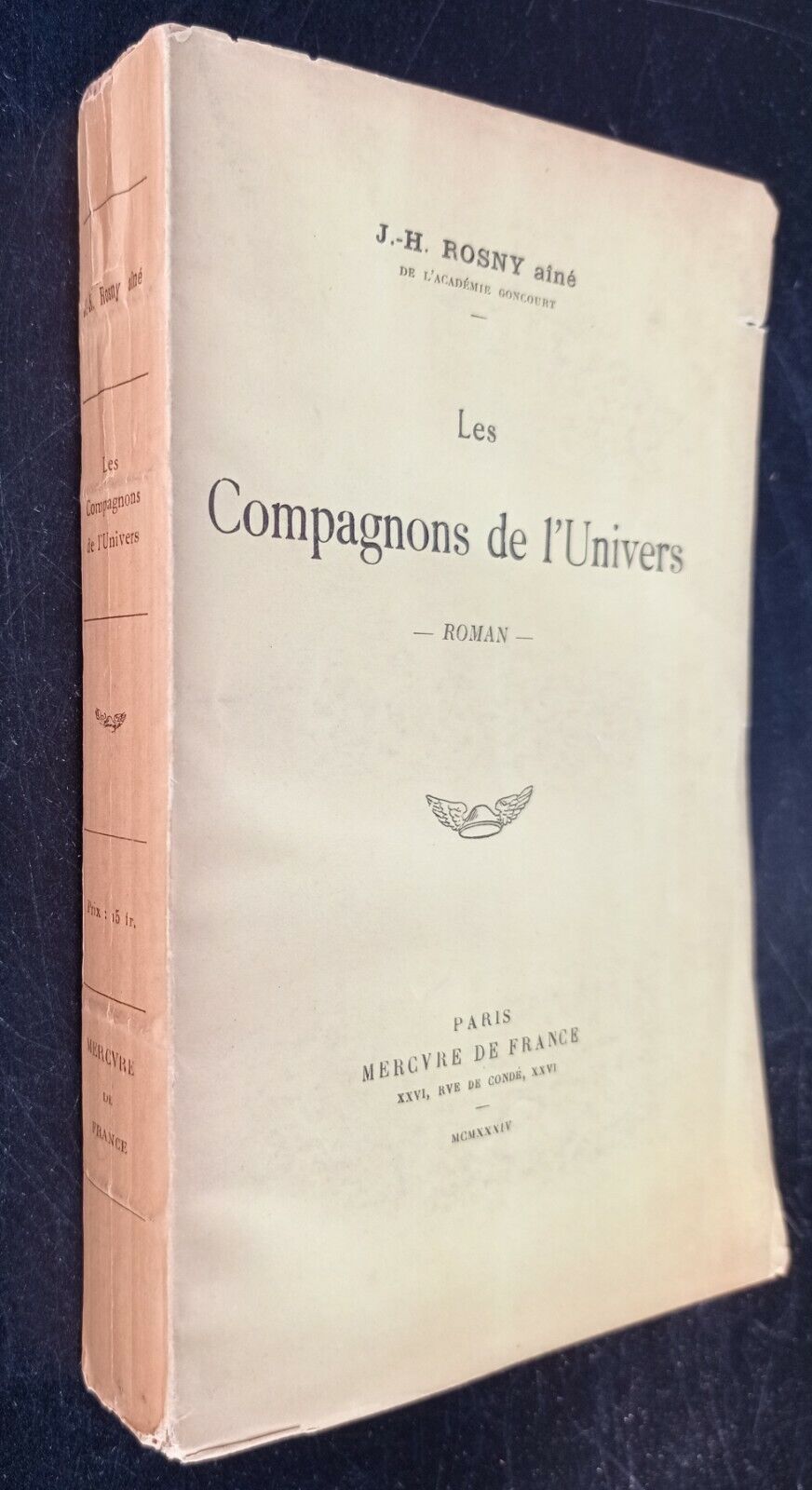

- J.-H. Rosny aîné’s Les compagnons de l’univers (Companions of the Universe) is Rosny’s last, great novel, a brilliant scientific romance in which a secret group of physicists attempts to breach the limits of the universe beyond photons, sub-particles and wave-sequences; while at the same time offering an in-depth study of the perversity of human sexual relationships. A lyrical meditation in the vein of his 1889 semi-mystical speculative essay on creation and Evolution, La légende sceptique.

- Gerald Bullett’s Eden River is a utopia set along the river known as Eden Here, beginning with Adam and Eve, and tracing the lives of their descendants.

- Francis Flagg’s “The Mentanicals” (Amazing Stories, April 1934). A scientist creates a time machine and an impulsive friend named Bronson takes it into the future. There he discovers a world of ruinous tall buildings inhabited by weird cylinder robots (rendered like killer hot water tanks by Leo Morey) and men reduced to savagery. Like Wells’s time traveler, Bronson loses the machine and can’t get back. He tries to communicate with the beast-men but to no avail. He explores finding strange museums filled with tools. He eventually discovers a collection of magazines and books that explain the history after modern times. A scientist named Bane Borgson invents a mechanical brain-cell that leads to the invention of the Mentanicals. These floating robots take over all the labor of humanity, eventually growing beyond their servant role and become the masters. Artificial intelligence.

- Jack Williamson’s novelette Born of the Sun. (Included in Asimov’s Before the Golden Age collection (1974); one of his favorite stories from this era.)

- E.E. “Doc” Smith’s Skylark of Valeron (in Astounding). A big circulation booster for the magazine. But Moskowitz in Seekers of Tomorrow suggests that this book got out of Smith’s control and was unwieldy.

- Susan R. Grayzel mentioned to me The War Upon Women — I can’t find info.

- Sam Moskowitz claims the first “generation starship” story to be Laurence Manning’s “The Living Galaxy” (September 1934 Wonder Stories). However the SFE suggests that since the story is set in a small, self-powered world, it does not fully embody the concept. Also see Simone Caroti’s The Generation Starship in Science Fiction: A Critical History, 1934-2001 (2011).

- George Weston’s His First Million Women is a satire of the “new Adam” theme in sf. Reprinted in Britain as Comet Z (1934). It’s an early version of the sf topos where sterility affects all but one man – an Adam and Eve-associated topic more widely used after the first nuclear explosion. Weston’s protagonist uses his new status to promulgate near-future disarmament, until the dissipation of Comet “Z”‘s effects makes it possible for him to be ignored.

- Clark Ashton Smith’s “The Plutonian Drug” (Amazing Stories, September 1934).

- David H. Keller’s “The Literary Corkscrew” — appears in the 1980 anthology Science Fiction: The Best of Yesterday.

- Donald Wandrei’s “The Blinding Shadows” (Astounding Stories, May 1934; in which the title’s “The” is dropped in the interior.) A “thought variant” story. Ashley’s Time Machines says it’s a very good story — ingenious invasion from another dimension.

- C.L. Moore’s “The Bright Illusion” (Astounding, October 1934). Ashley’s Time Machines notes that this story is part of the great flourishing of Astounding in 1934. A thoughtful alien love story.

- Nat Schachner’s “The Living Equation,” in which a computer creates its own universe. AI? Ashley’s Time Machines notes that this story is part of the great flourishing of Astounding in 1934./li>

- Harl Vincent’s “Rex” — about a robot surgeon. Ashley’s Time Machines notes that this story is part of the great flourishing of Astounding in 1934.

- John Russell Fearn’s “Before Earth Came.” Ashley’s Time Machines notes that this story is part of the great flourishing of Astounding in 1934.

- Donald A. Wollheim’s “The Man from Ariel” is a touching tale of a dying alien. Wollheim (1914-1990) was one of the first and most vociferous sf fans, along with Forrest J Ackerman. Wollheim’s first published story was “The Man from Ariel” for Wonder Stories in January 1934 (for which Hugo Gernsback notoriously did not pay him until threatened with court action), but he did not begin to publish fiction with any regularity until the 1940s.

- Chester D. Cuthbert’s “The Sublime Vigil.” Mood story about a man who has lost his girlfriend to a cosmic forc.e Later acknowledged by Gernsback as one of his favorite stories. Gernsback published two of the Canadian writer’s stories in the February and July 1934 issues of Wonder Stories. Fun fact: Chester’s book collection was frequently mentioned in the few scholarly journals that have studied the Fantasy and Science Fiction fields. A permanent repository for his book collection (at one time reputed to be the largest such collection in Canada) has been found in the University of Alberta’s Library as the Chester D. Cuthbert Collection.

- Eando Binder’s “The Spoor Doom” (Wonder). Prediction of germ warfare and humans surviving underground.

- R.F. Starzl’s “The Last Planet” (Wonder). Depicts the last remnants of humanity millions of years in the future seeking refuge on Mercury. Almost the first generation-starship story. Fun fact: His first story is his best remembered, “Out of the Sub-Universe” (Summer 1928 Amazing Stories Quarterly) where a man and woman descend into a sub-atomic world (see Great and Small), and a half-hour later by Earth-time several hundred descendants return because a million years have passed in their world.

- Edmond Hamilton’s “Colonists of Mars.” In the December 1952 issue of Thrilling Wonder Stories, editor Samuel Hines will present “What’s It Like Out There?” as the culmination of Edmond Hamilton’s evolution from a “primitive period” of writing extravagant pulps to “grown up” tales of “human emotion.” However, Hamilton wrote the story in 1933 — but couldn’t find a publisher as it was “too gruesome, too horrible.” Found later by Leigh Brackett in a file, Hamilton rewrote the tale. Here Hamilton argues that returning spacemen will experience similar trauma to that of war veterans. And just like we glamorize war in media, the dangers of space travel (both physical and mental) are sanitized by gaudy pulp adventures. The story succeeds as a complex analysis of the tales we tell each other to obfuscate traumatic experiences and give comfort to those suffering loss. Ashley’s Time Machines calls it a top-quality story about a hostile and near-fatal expedition to Mars.

- Clifton B. Kruse’s “Dr. Lue-Mie.” Ashley’s Time Machines notes that this story is part of the great flourishing of Astounding in 1934. A scientist experiences termite life

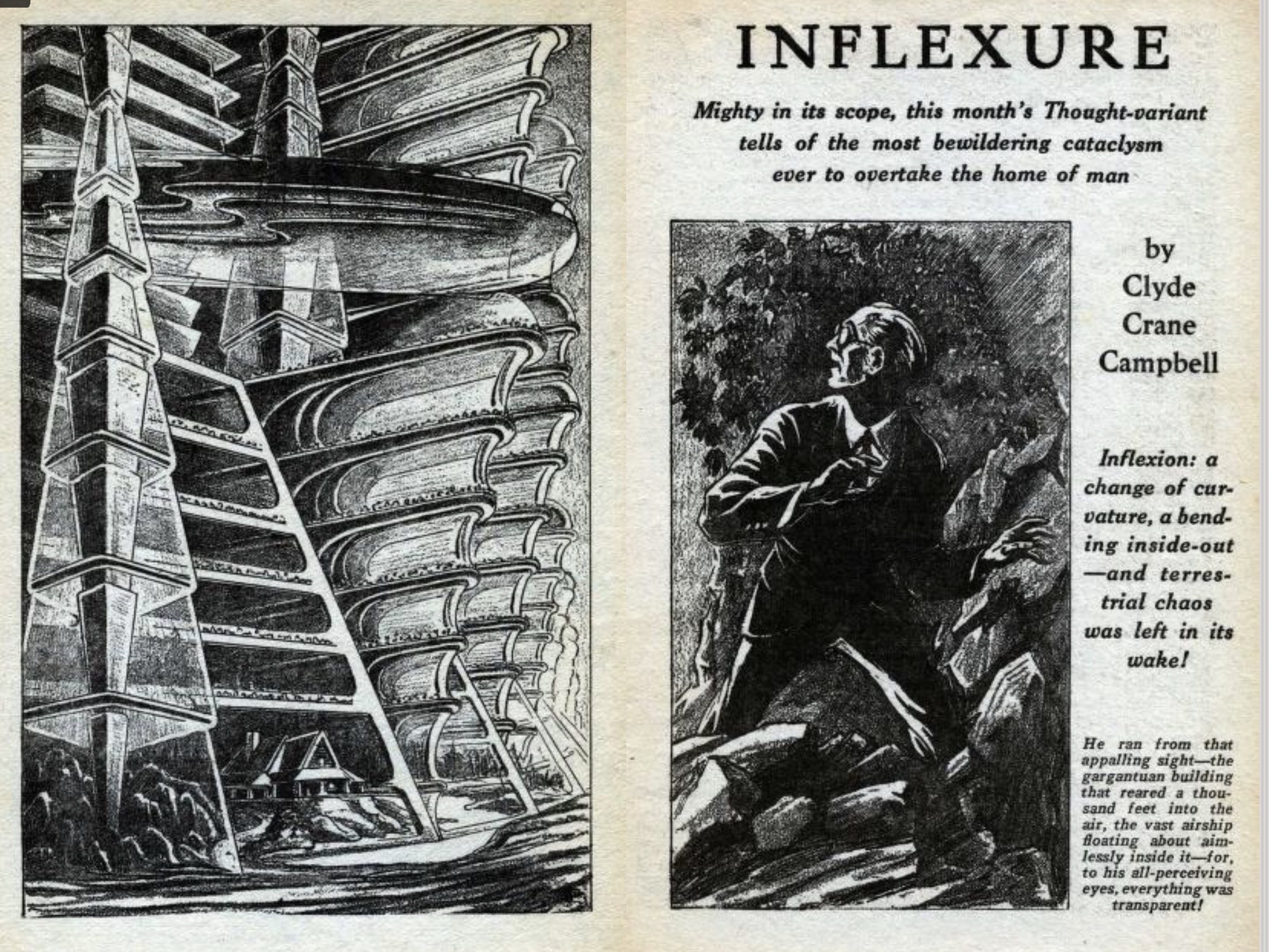

- Clyde Crane Campbell (H.L. Gold)’s “Inflexure” in Astounding (October 1934). A :thought variant” depicting all time existing simultaneously. Excerpt:

“We are the Chosen of God,” the tall leader said to the fainting man in queer, archaic Hebrew. “I am Joshua, leader of the Children of God. We take possession of this land of milk and honey, that our children and their children’s children may prosper and increase as the sands of the sea.”

Campbell’s first work of genre interest; he used a pseudonym until 1938, he’d later recount, because of the antisemitism of the magazines’ publishers. He was later assistant to Mort Weisinger on the magazines Captain Future, Startling Stories and Thrilling Wonder Stories (1939-1941). In 1950 he started Galaxy Science Fiction, which from the outset he made one of the leading sf magazines, and for the editing of which he remains best known – indeed, notorious. Ashley’s Time Machines notes that this story is part of the great flourishing of Astounding in 1934.

- A. Merritt’s “The Last Poet and the Robots.” An early-ish story about mechanical robots with conscious minds. Narodny, the titular poet, is a Russian superman — a mad scientist and poet, and ruler of the renegade super-humans. He and his fellow supermen can’t be bothered to leave their Glass Bead-like exile until it occurs to them that the robots who rule the outside world cannot create art. The story was part of a round-robin novel first published in the April 1934 issue of Fantasy Magazine, a fanzine. (John W. Campbell, E. E. “Doc” Smith, and Edmond Hamilton also contributed to this fanzine.) Merritt’s story was the only chapter to be reprinted as a story in a professional magazine (Thrilling Wonder Stories, October 1934). In 1949 it was published in book form in the collection The Fox Woman.

- Richard Vaughan’s The Exile of the Skies (January-March 1934 Wonder Stories). Seared into the memories of 1930s pulp magazine readers, one hears, as among the best serials of the period. It’s in the mould of E.E. Smith’s Skylark series, but more thoughtful in its depiction of a ruthless but philanthropic super-scientist who plans to take over the world for its own good… but is exiled into space. The novel follows his travels through space, until he returns to save Earth from new alien perils. Although overwritten, even by the standards of the day, it’s breathtaking scope and vision imparted a powerful sense of wonder. Any trace of Vaughan was thereafter lost.

- Berilo Neves’s collection Século XXI. In the 1930s, the light, amusing, sf short stories by journalist and writer Berilo Neves (1901-1974) achieved an unprecedented success among Brazilian readers. This is the third and final collection. The sf elements serve only to precipitate situations involving jealousy, amorous conquests and infidelities.

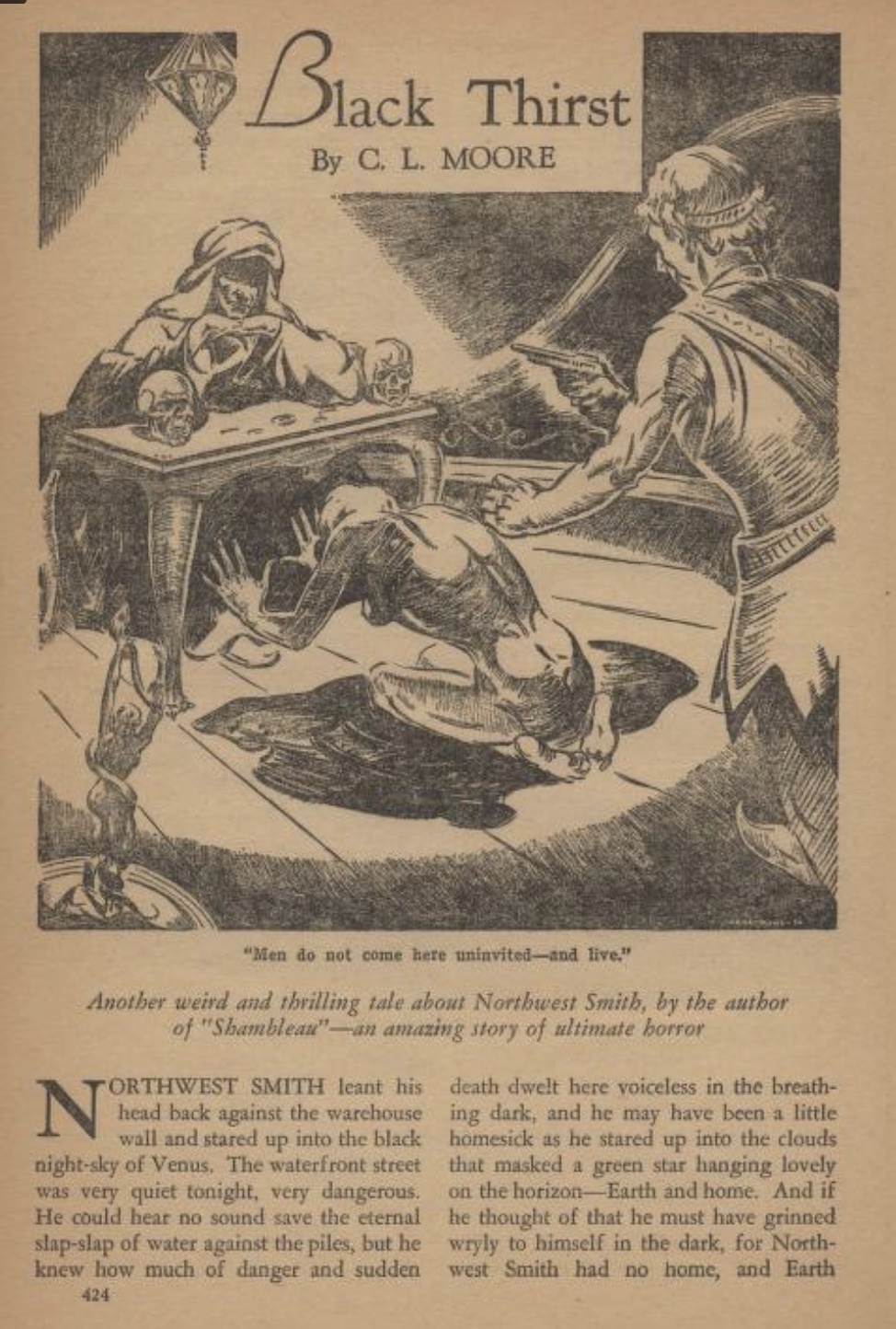

- C.L. Moore’s “Black Thirst.” The second Northwest Smith story, published in the April 1934 issue of Weird Tales shortly after “Shambleau.” Smith is a spaceship pilot and smuggler who lives in an undisclosed future time when humanity has colonized the Solar System. Here he is approached by one of the fabled Minga women, an odalisque from a line of legendary beauties. Vaudir wishes to secure Smith’s services, an unheard of request from a secretive woman of beauty and virtue. She fears that she will vanish like so many other Minga girls. Delves into the potential horrors of eugenics; what sinister end does the breeder have in mind. Influenced by Gothic literature, like other Moore stories — the sort of thing that Campbell would work to extricate from sf.

- C.L. Moore’s “Scarlet Dream” (Weird Tales, May 1934). A Northwest Smith adventure. An oddly patterned shawl that Northwest picks up in Lakkdarol gives him unpleasant dreams.

- C.L. Moore’s “Dust of Gods” (Weird Tales, August 1934). A Northwest Smith adventure. Northwest and Yarol take a job searching for the physical remnants of a dead god in northern Mars.

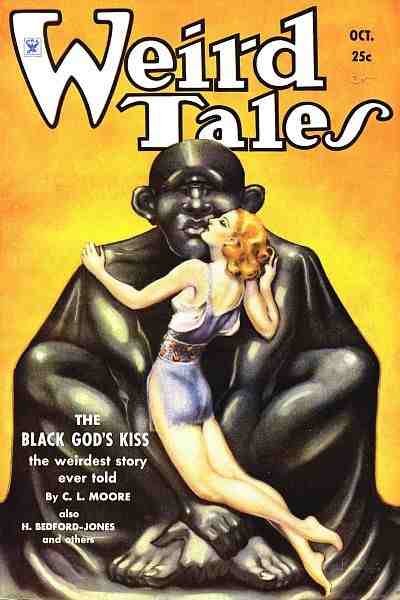

- C.L. Moore’s Jirel of Joiry stories (serialized 1934–1939). Moore’s five Jirel of Joiry stories appeared in Weird Tales during the Golden Age of Fantasy. We first meet the redheaded Jirel, an arrogant, passionate, indomitable adventurer, late in her career, after she’s become ruler of Joiry, a version of Dark Ages France. In “Black God’s Kiss” (“the weirdest story ever told,” according to the magazine’s cover blurb), Castle Joiry has been captured by Guillaume, a handsome fellow who forces his attentions on Jirel; she escapes into a Hieronymus Bosch-esque realm where she encounters squishy, slavering things, blind horses, and other nightmarish horrors before returning home armed against Guillaume with the madness-inducing kiss of the titular god. (“Black God’s Shadow” involves a mission of mercy, where she must battle the Black God for Guillaume’s soul.) In “Jirel Meets Magic,” our heroine is imprisoned in a chamber with many doors, each of which opens onto a different alien landscape; in “The Dark Land,” Jirel is required to pay the price for having traveled too often in other dimensions; and “Hellsgarde” is a kind of treasure-hunt uncannily reminiscent of Christopher Nolan’s Inception. There is some action in these yarns, but they’re mostly about atmosphere: As Adam McGovern puts it, “Moore’s style is a ballad-slam of hypersensory description, serpentine in high-frequency alliteration and assonance, propelling of the narrative while saturating in the impressions of how it all feels.” “The Black God’s Kiss” is collected in Lisa Yaszek’s excellent 2018 collection The Future Is Female! 25 Classic Science Fiction Stories by Women. Fun facts: Readers at the time didn’t realize that Moore was a woman; in fact, she was among the first women to write in the science fiction and fantasy genres. One such reader was sci-fi author Henry Kuttner, who ended up co-authoring the 1937 story “Quest of the Starstone” with her — a crossover featuring Jirel and the heroes of Moore’s sci-fi Weird Tales series, Northwest Smith. Moore and Kuttner would marry in 1940.

- Francis Flagg’s “The Distortion Out of Space” (Weird Tales, August 1934) is Flagg’s Lovecraftian piece. Borrowing ideas from Lovecraft’s “The Colour Out of Space”, Flagg creates a similar set-up. Two campers in Arizona see a meteorite fall on Bear Mountain and go to investigate. On the way they stop off at the cabin of Henry Simpson. The roof of the shack shows damage from the fallen stone but inside something even stranger has occurred. In the bedroom of Henry and Lydia Simpson is a vast distortion, an abyss of dimensional space that does not follow normal physics. One man goes into the distortion to find Henry’s wife while the narrator hangs back at the door to lead him out. Eventually he takes a rope and follows his friend in. Lost and desperate he fires his revolver. The shot accidentally kills the alien who is creating the distortion. The three humans find themselves back in a normal room. The narrator, who shared his thoughts with the alien, knows of its great loneliness and pain. He weeps.

- Alexander Laing’s The Cadaver of Gideon Wyck. A murder novel that hinges on experiments in genetic engineering inflicted upon pregnant women. Laing is best known for his books on the sea, and for editing influential anthology The Haunted Omnibus (1937). recommended to my attention by Frank Cioffi.

- A.M. Low’s Adrift in the Stratosphere (17 February-21 April 1934 Scoops as Space). A juvenile sf novel, whose young protagonists accidentally take off in a professor’s experimental spaceship and find themselves attacked by irrationally hostile Martians with various Rrys and a madness-inducing basilisk radio broadcast. There are subsequent tours of utopias set on space islands. Radium is the basis of a fantastic weapon. Low was a UK academic, inventor and author, president of the British Interplanetary Society for a period; in 1917, during his service in World War One, he was partially responsible for the invention of a flying bomb.

- Walter Harvey’s Strange Conquest. Eccentric sf thriller set in the late twentieth century. Fear of the unknown and unexplained brings religious awakening and unites nations of the world imperiled by “The Professor,” an immortal superman who has harnessed an unknown energy source and constructed a death ray with which he crushes all efforts, including the deployment of an army of robots (they are annihilated), to defeat his plan to establish a new world order. Ultimately, the dictator who is “mad” but benevolent, uses his energy beam to pull the moon closer to earth so it can be colonized. Embedded in this framework are accounts of the subterranean city of Tur, inhabited by an advanced industrialized society, where “The Professor” was imprisoned for twenty years after losing a power struggle with the nation’s “Director of Policy,” and an account of Parva, an island colony founded by biologists who have scientifically created humans (both superior and inferior men bred for placement in the four ranks of Parvan society) whose young citizens are suddenly dying by the thousands because they have developed no “inner life” and cannot cope with the “great depression” which has enveloped the nation as “religion, which is the world’s finest preservative, has been abolished.”

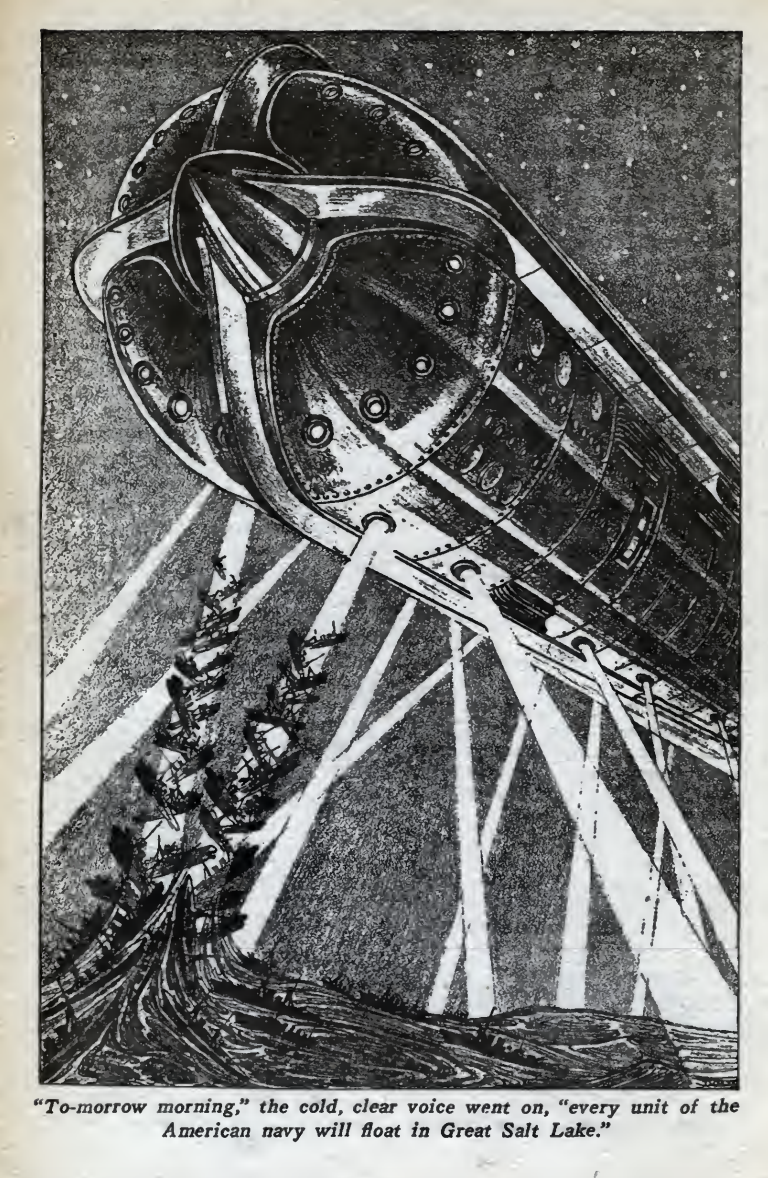

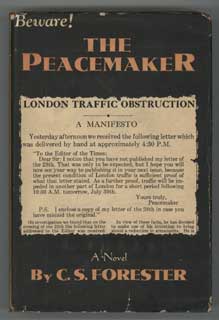

- C.S. Forester’s The Peacemaker. “A bitterly ironic story about an ineffectual schoolmaster whose mathematical genius leads him to construct a machine which will demagnetize iron at a distance. He is led by unfortunate circumstance to use the machine in a hopeless attempt to blackmail England into initiating a program of disarmament.” – Anatomy of Wonder

- David H. Keller’s Life Everlasting (July-August 1934 Amazing). Here, the human race must choose between a sane and sanitary immortality and fertility; it chooses the latter.

- Donald Wandrei’s “Colossus” — the cover story of the January 1934 ish of Astounding. Ashley says the concept is not original but the breakneck energy is thrilling. Ashley’s Time Machines notes this story is an exemplar of Astounding‘s new policy that stories should be “thought variants.” Followed in December 1934 by “Colossus Eternal.” (Included in Asimov’s Before the Golden Age collection (1974); one of his favorite stories from this era.)

- George Schuyler’s “The Beast of Bradhurst Avenue: A Gripping Tale of Adventure in the Heart of Harlem” (March-May 1934 Pittsburgh Courier), about a German mad scientist’s attempts to graft the brains of decapitated black women onto dog bodies.

- Gunnar Serner’s Herr Collin kontra Napoleon [“Mr Collin versus Napoleon”] Sernar was an internationally successful Swedish thriller and adventure writer who wrote as Frank Heller. Here, he incorporates speculative and imaginative elements.

- Nat Schachner’s “Redmask of the Outlands.” A very popular story for Astounding, about a future America divided between high-tech city states and primitive wildernesses.

- Hans Dominik’s “A Free Flight in 2222” (Austria). Collected in The Black Mirror (Wesleyan).

- J. Leslie Mitchell’s Gay Hunter. The eponymous female protagonist is cast forward in time — via a process explicitly justified by J W Dunne’s time theories — arriving naked along with two Mosleyite fascist males and a spoiled English aristocratic lady. It’s a ruined-earth Britain 20,000 years hence. Unlike her co-travelers, she adapts with commendable swiftness to local mores, accepting her nakedness. She contemplates the post-nuclear-war ruins left by long-extinct fascist “Hierarchs,” strewn across the landscape. Eventually, in climactic scenes in ruined London she helps defeat her fascist companions’ attempt to re-industrialize, re-weaponize and ultimately re-destroy the new Golden Age of the world.

- John Gloag’s Winter’s Youth. Political satire – conflict between young and old. The British government, in the near future, attempts to remain in office first by patriotic touting what turns out to be a forged Fifth Gospel focused on ancient Britain, and then via a rejuvenation process partially based on Serge Voronoff’s monkey glands, but more sophisticated. The aspirational secret masters of the British Medical Association hope to create a eugenically sound society by restricting access to this process to elderly white males with the proper credentials, but these gentlemen suffer what amounts to devolution, turning into bloodthirsty sexual predators with a taste for flagellation. Much of the tale is focused on press manipulations of the mounting chaos; the unrestricted use of a weapon using nuclear energy generates a disastrous war in the 1960s. The survivors resume life as before.

- John W. Campbell’s “Atomic Power” (Astounding, December 1934). In their intro to “Atomic Power,” the editors of The Ascent of Wonder suggest that, as editor of Astounding from 1937, Campbell was reluctant to print disaster stories, a mainstay of speculative fiction from its early days and a form that would be embraced by the New Wave. Yet “Atomic Power” is in fact a gruesome and apocalyptic disaster story. The Earth begins to spiral away from the sun, so that temperatures drop rapidly and New York is buried under many yards of snow. Buildings, bridges and machines fail as their metal components weaken and break. Campbell throws lots of science at us, but also horrific vignettes of panicked crowds boarding the last ocean liner out of New York and causing it to capsize, and individuals whose limbs come off and whose hearts burst because they have exerted themselves and “the chemical power of muscles remained undiminished, while their tensile strength declined…people tore themselves apart by the violence of their struggles.” Scientists invent a nuclear reactor and propagate a “counterfield” throughout the universe that restores gravity and intermolecular bonds to normal. The day is saved, but more amazing yet is the sense of wonder ending we get which was foreshadowed in that prologue about the students: our universe is a molecule of a superuniverse, in which atomic reactors power a civilization by breaking down molecules–the diminution of intermolecular bonds was the start of the process of that superuniverse reactor breaking down our universe! (A year in our universe is a millionth of a second in that superuniverse.) Our universe was saved by building a nuclear reactor that operates by annihilating other universes! Our own civilization’s survival is predicated on committing mass genocide of other universes.

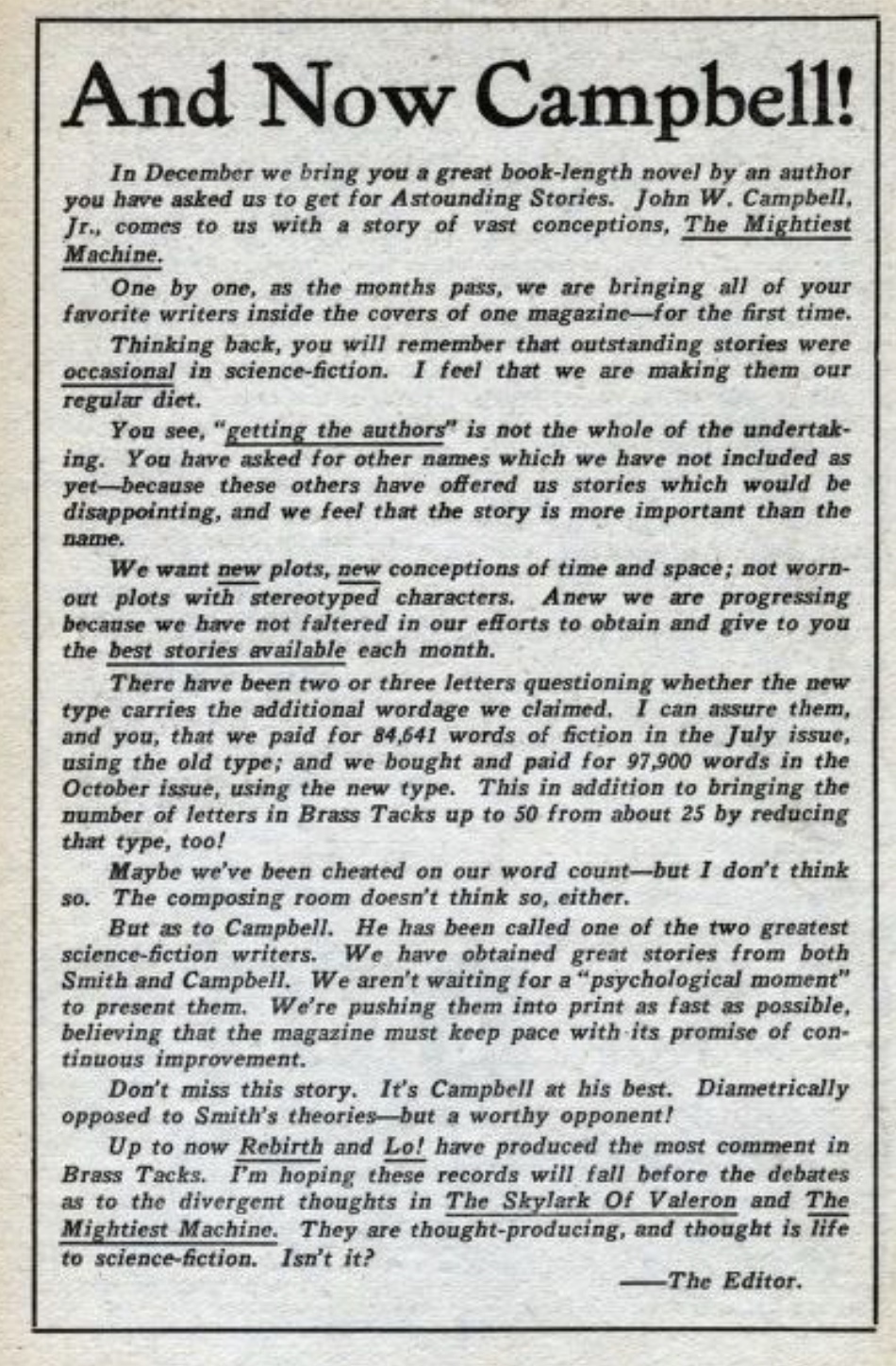

- John W. Campbell’s The Mightiest Machine. Cover story, December 1934-April 1935 Astounding. Novel serialized in five parts; as a book, 1947. The story is the first to feature Campbell’s hero Aarn Munro. This space opera novel concerns the harnessing of energy from the sun and encounters with aliens who turn out not to be truly alien at all. It also touches on the legends of ancient civilizations on earth, Mu in this case, and what may have happened to them. Includes a wide range of advanced technology including space travel concepts such as artificial gravity, faster-than-light travel with warp drive, and an early version of travel through wormholes. The protagonist also invents and employs devices such as infrared vision googles and miniature remotely piloted surveillance drones. Ashley’s Time Machine calls it a blockbuster that shows the maturing of the space opera. (Let’s beware of the rhetoric of maturity in sf). Moskowitz in Seekers of Tomorrow says this one epitomizes the stories that had made Campbell such a popular writer. Astounding reviewer P. Schuyler Miller described the 1947 edition as “perhaps the climax of the super-physics school of science fiction which ‘Skylark’ Smith had started.” Everett F. Bleiler identified the novel as the paradigm of “the Campbell hard space opera,” noting its “great quantity of fanciful and ingenious scientific extrapolations, fictional weaknesses, and polarized social simplistics that regard genocide with equanimity.” But Scott Bradfield says: “Campbell’s early stories remain almost uniformly risible, focusing on problem-solving space adventurers who sit around exchanging endless expository dialogue such as: ‘You should talk!’ Russ Spencer laughed. ‘One of the features of that ship is the new Carlisle air rectifiers, guaranteed to maintain exactly the right temperature, ion, oxygen, and ozone content as well as humidity control.’” (This is from The Mightiest Machine.) Fun fact: The novel contains the phrase “…to infinity and beyond…”

- E. E. “Doc” Smith’s What a Course! (First appeared in Fantasy Magazine in 1934 as part of the “Cosmos: serial.) A 1939 short-story variant, “Robot Nemesis,” appears in various anthologies.

- John Wyndham (John Beynon Harris)’s “The Man from Beyond” (Wonder Stories). A novelette. “The writer attempts to bring out a side of human nature that few authors touch upon. Gratz hates mankind because of its evil greed and lust for power. He denounces his own kind to an alien intelligence. And then the tremendous truth is revealed to him.” Moskowitz says it’s the last story from the first phase of his US writing career

- Leslie F. Stone’s “The Rape of the Solar System” (Amazing Stories, December 1934).

- Muhammadu Bello Kagara’s (1890–1971) Gandoki. Here we see speculative fiction from the Muslim world emerging as a form of resistance to the forces of Western colonialism. The author is a Nigerian Hausa; the novel is set in an alternative West Africa. In the story, the natives are involved in a struggle against British colonialism. There is resistance as well as travel to other realms and phantasmagorical experiences with djinn. Is it fantasy or sf? Seems like fantasy. See this site and this one.

- Murray Constantine’s (pseudonym of Katharine Burdekin) Proud Man. A didactic essay/fiction about gender, proto-feminist. Using the device of time travel, Burdekin places a protagonist who is both male and female, comes from an advanced future civilization, and is identified as the Person in England of the 1930s. The Person comments on that society with the distanced and often bemused glance of . . . a human, as opposed to the less evolved “subhumans” of the twentieth century. Given refuge and education by a priest, the Person lives first as a woman and then as a man, observing, revealing, and ultimately going on to heal, all with a coolness that sympathetically penetrates to the core of subhuman suffering: “A privilege of class divides a subhuman society horizontally, while a privilege of sex divides it vertically. Subhumans cannot apparently exist without their societies being divided, preferably in both these ways.” Praised by Scottish poet Edwin Muir as “the most profound and brilliantly sustained satire that has appeared for many years.” See this list of Pre-1950 Utopias and Science Fiction by Women

- Murray Leinster’s “Sidewise in Time” (novella, Astounding Stories, June 1934). Alternate histories are juxtaposed. Leinster was an early writer of parallel universe stories. Four years before Jack Williamson’s The Legion of Time came out, Leinster published this story. Leinster’s vision of extraordinary oscillations in time had a long-term impact on other authors, for example Isaac Asimov’s “Living Space”, “The Red Queen’s Race”, and The End of Eternity. A very early Parallel Worlds tale, possibly the earliest example in the genre of the Alternate History. It lent its name to the Sidewise Award, established in 1995 for the best alternate history story of the year. Often reprinted. Listed in the Cambridge Companion to SF chronology. Ashley’s Time Machines notes that this story is part of the great flourishing of Astounding in 1934. (Included in Asimov’s Before the Golden Age collection (1974); one of his favorite stories from this era.)

- Murray Leinster’s “The Mole Pirate” (novella, November 1934 Astounding) is considered one of Leinster’s best from this era. Jack Hill, a young scientist, has invented a method of aligning the atoms of a material so that it can pass through most other materials; this process of aligning atoms can be reversed just as easily as it is initiated. Hill reveals the thirty-foot long torpedo-like vehicle he has built that takes advantage of his process: the Mole. But one of America’s top scientists, Durran, having announced that he was rejecting all conventional morality and taking up a life guided entirely by selfishness, hijacks the Mole. Sam Moskowitz included “The Mole Pirate” in his oft-republished anthology of three short novels that has appeared variously as A Sense of Wonder, The Moon Era, and Three Stories. In his introduction to the 1967 book, Moskowitz complains that current SF too often has “dispensed with the romance” and “literary ‘magic'” that gave readers of earlier SF “emotional breathlessness as well as intellectual stimulation.” Moskowitz tells us he selected the three works in A Sense of Wonder because they exemplify his idea of what “a sense of wonder” is and also have the literary merit modern practitioners claim earlier SF lacked.

- Nat Schachner’s He from Procyon (a “thought variant novel,” Astounding, April 1934). A bored alien (who looks like an archangel) from an advanced race implants six humans with devices attached to their pineal glands, as part of an impish experiment. One of these new supermen, Jordan, has big plans: “He was fully aware by now of his peculiar gift. Just what it meant scientifically, he neither knew nor cared. He had a definite vision of himself as a second Mohammed, a new Alexander, a greater Mussolini or Hitler. His ambition vaulted. The police commissionership already seemed petty. Mayor was better, governor even; yes, the very presidency itself. And why stop there, he had already asked himself? Alfred Jordan the First, Dictator of the World! Dazzling fantasy!” The other supermen are more humble, though. One hears echoes of Trump in this story:

“People of the United States,” he said. “This is Alfred Jordan the First addressing you. You are all to listen to me and obey in all things. This country had been suffering from misrule long enough. It has been going from bad to worse; your leaders have been inefficient and criminally foolish. You need discipline, a strong hand over you, a man with vision and power. Then you will rise to your rightful place as a great nation, with food and plenty for every one, with the respect of the world beating on your shores.

“I am your new dictator, and my lightest word shall be your law. The overthrow of the present stupid government is complete. My army has met and defeated the governmental troops. The president and Congress have fled from my wrath. I am in full control; the seat of the government shall continue as before at Washington. You are to resume normal activities, always obedient to my will.”

Fun facts: One character is named Doolittle and later we meet a Doctor Hugh Lofting.

- Katharine Burdekin’s [“Murray Constantine”] The Devil, Poor Devil! See this list of Pre-1950 Utopias and Science Fiction by Women.

- Monica Curtis’s Landslide. See this list of Pre-1950 Utopias and Science Fiction by Women.

- Raymond Z. Gallun’s “Old Faithful” (in Astounding, December 1934 — same issue as Campbell’s Mightiest Machine and “Atomic Power” and Wandrei’s “Colossus Eternal”). A touchingly sentimental reply to Wells’s War of the Worlds. Gallun was an unusually thoughtful pulp writer. Tells of one of the last Martians who attempts to cross space to Earth. A strange, tentacled, but sympathetically conceived alien who is supported in his rebellion against a rigid society by friends from Earth. It was very popular. Instantly recognized as a classic. Gallun’s sympathetic portrayal of a very alien being since become one of the most beloved and reprinted science fiction stories of all time. Sequel is “The Son of Old Faithful.” (Included in Asimov’s Before the Golden Age collection (1974); one of his favorite stories from this era.)

- Robert E. Howard’s Almuric. Howard started to write Almuric (a non-Conan, but still atavistic sword-and-planet sf novel) but abandoned it halfway. The novel features a muscular hero known on earth as Esau Cairn, a complete misfit in modern America who “belongs in a simpler age”. Exploited by a corrupt political boss whom he finally kills with his bare hands, Cairn must flee. A sympathetic scientist helps him get to Almuric, a savage but habitable world in another universe. Cairn must gather and hunt his food and battle various bizarre animals. Eventually he stumbles upon the native people of Almuric, the Guras, who are hairy, ape-like men with a violent but pragmatic way of life. They live in great fortified cities and wage endless wars against each other, carbine and sword being their weapons of choice. Cairn begins to enjoy this new, simpler and truer existence, and his strength and fighting prowess earn him the nickname Ironhand. It was published posthumously in Weird Tales, serialized in three parts beginning in May 1939. Fun facts: There is some question as to whether Robert E. Howard is the true author of Almuric. It was not published until after his death and some speculate that it was written by his editor, Otis Adelbert Kline. In 1980, Marvel Comic’s magazine Epic Illustrated published a comic book version of the story, a limited series in four parts written by Roy Thomas and drawn by Tim Conrad. It was later reprinted in graphic album form by Dark Horse in 1991.

- Stanley G. Weinbaum’s “Valley of Dreams” is a hastily expanded version of “A Martian Odyssey” because readers demanded more.

ALSO: Marie Curie dies. Fermi suggests that neutrons and protons are the same fundamental particles in two different quantum states. Hindenburg dies; German plebiscite elects Hitler as Führer. FBI shoots John Dillinger. Hergé’s Tintin adventure Le Lotus bleu (serialized 1934–1935); James M. Cain’s The Postman Always Rings Twice; Milton Caniff’s comic strip Terry and the Pirates (1934–1946); Rex Stout’s Nero Wolfe/Archie Goodwin adventure Fer-de-Lance. Fitzgerald’s Tender is the Night, Graves’s I, Claudius. Capra’s It Happened One Night, Ford’s The Lost Patrol, Lubitsch’s Design for Living.

Here’s an innovation from c. 1934 that would revolutionize sf publishing: the paperback book as we know it. While waiting at Exeter’s train station in 1934, Allen Lane was returning home, and while waiting, was looking for something to read outside of magazines and poorly-reprinted novels. He wasn’t able to find anything, and began thinking about how the public would benefit from a line of high-quality paperbacks that would be affordable to the masses. He went on to found Penguin.

Jack Parsons, Edward Forman, and Frank Malina form the Caltech-affiliated Guggenheim Aeronautical Laboratory (GALCIT) Rocket Research Group, which during WWII would become the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL). Beginning in 1939, Parsons would come to believe in the reality of Thelemic magick (the new religious movement founded by the English occultist Aleister Crowley) as a force that could be explained through quantum physics.

Sheldon Cheney’s Expressionism in Art (1934) draws an explicit connection between modern, abstract art and spiritual teachings. But in the 1930s–1940s, the spiritualist/theosophical origins of abstract art were quietly airbrushed from history… no doubt because Hitler’s fascination with the occult made it wiser for intellectuals interested in aesthetic issues to focus on purely aesthetic, rather than spiritual, themes. (See Alfred H. Barr’s — director of MoMA — purely aesthetic chart of artistic movements, c. 1936, which Meyer Schapiro called “unhistorical”; or the critic Clement Greenberg’s emphasis on form over content.)

Karl Popper, the philosopher of science who grew up in Vienna during the heyday of the Vienna Circle — the philosophers of science who elaborated logical empiricism, which would become the dominant philosophy of science in Europe and the USA — would in 1934 develop a divergent framework for understanding scientific thought, articulated in The Logic of Scientific Discovery.

Popper argues that science should adopt a methodology based on falsifiability, because no number of experiments can ever prove a theory, but a reproducible experiment or observation can refute one. See entry for 1919.

Ruth Benedict’s Patterns of Culture argues that “a culture, like an individual, is a more or less consistent pattern of thought and action”; each culture chooses from “the great arc of human potentialities” only a few characteristics. (She desired to show that each culture has its own moral imperatives that can be understood only if one studies that culture as a whole. It was wrong, she felt, to disparage the customs or values of a culture different from one’s own.)

After serving as a naval officer for five years, in 1934 Robert Heinlein retires due to ill-health, and studies physics at the University of California Los Angeles for a time. He will then take a variety of jobs before beginning to publish sf in August 1939 with “Life-Line” for Astounding. Isaac Asimov‘s first published work was a humorous item on the birth of his brother for Boys High School’s literary journal in 1934; he would strike up a friendship with John W. Campbell in 1938 and begin publishing his sf stories in 1939. A.E. Van Vogt was active for several years in various other genres before first publishing an sf story in July 1939 and establishing himself as the first Canadian sf writer of real importance. In 1934 Ray Bradbury‘s father, a power lineman who was having trouble gaining employment in Michigan during the Depression, moved with the family to Los Angeles; memories and images of southern California would be central to Bradbury’s work, though the small-town Midwest always remained important in his stories.

MORE RADIUM AGE SCI FI ON HILOBROW: HiLoBooks homepage! | What is Radium Age science fiction? |Radium Age 100: 100 Best Science Fiction Novels from 1904–33 | Radium Age Supermen | Radium Age Robots | Radium Age Apocalypses | Radium Age Telepaths | Radium Age Eco-Catastrophes | Radium Age Cover Art (1) | SF’s Best Year Ever: 1912 | Radium Age Science Fiction Poetry | Enter Highbrowism | Bathybius! Primordial ooze in Radium Age sf | War and Peace Games (H.G. Wells’s training manuals for supermen) | Radium Age: Context series | J.D. Beresford | Algernon Blackwood | Edgar Rice Burroughs | Karel Čapek | Buster Crabbe | August Derleth | Arthur Conan Doyle | Hugo Gernsback | Charlotte Perkins Gilman | Cicely Hamilton | Hermann Hesse | William Hope Hodgson | Aldous Huxley | Inez Haynes Irwin | Alfred Jarry | Jack Kirby (Radium Age sf’s influence on) | Murray Leinster | Gustave Le Rouge | Gaston Leroux | David Lindsay | Jack London | H.P. Lovecraft | A. Merritt | Maureen O’Sullivan | Sax Rohmer | Paul Scheerbart | Upton Sinclair | Clark Ashton Smith | E.E. “Doc” Smith | Olaf Stapledon | John Taine | H.G. Wells | Jack Williamson | Stanisław Ignacy Witkiewicz | S. Fowler Wright | Philip Gordon Wylie | Yevgeny Zamyatin