RADIUM AGE: 1930

By:

November 12, 2022

A series of notes towards a comprehensive account of the science fiction genre’s Radium Age (1900–1935). These notes are very rough-and-ready, and not properly attributed in many cases. More information on Josh’s ongoing efforts here and here.

RADIUM AGE TIMELINE: [1900 | 1901 | 1902 | 1903] | 1904 | 1905 | 1906 | 1907 | 1908 | 1909 | 1910 | 1911 | 1912 | 1913 | 1914 | 1915 | 1916 | 1917 | 1918 | 1919 | 1920 | 1921 | 1922 | 1923 | 1924 | 1925 | 1926 | 1927 | 1928 | 1929 | 1930 | 1931 | 1932 | 1933 | [1934 | 1935]. (The brackets, here, indicate “interregnum” years — i.e., periods of overlap between sf’s Radium Age and its Scientific Romance and so-called Golden Age eras.)

Ashley’s Time Machines calls 1930 the year of “super-science fiction” — because of John Campbell Jr., E.E. Doc Smith, and others.

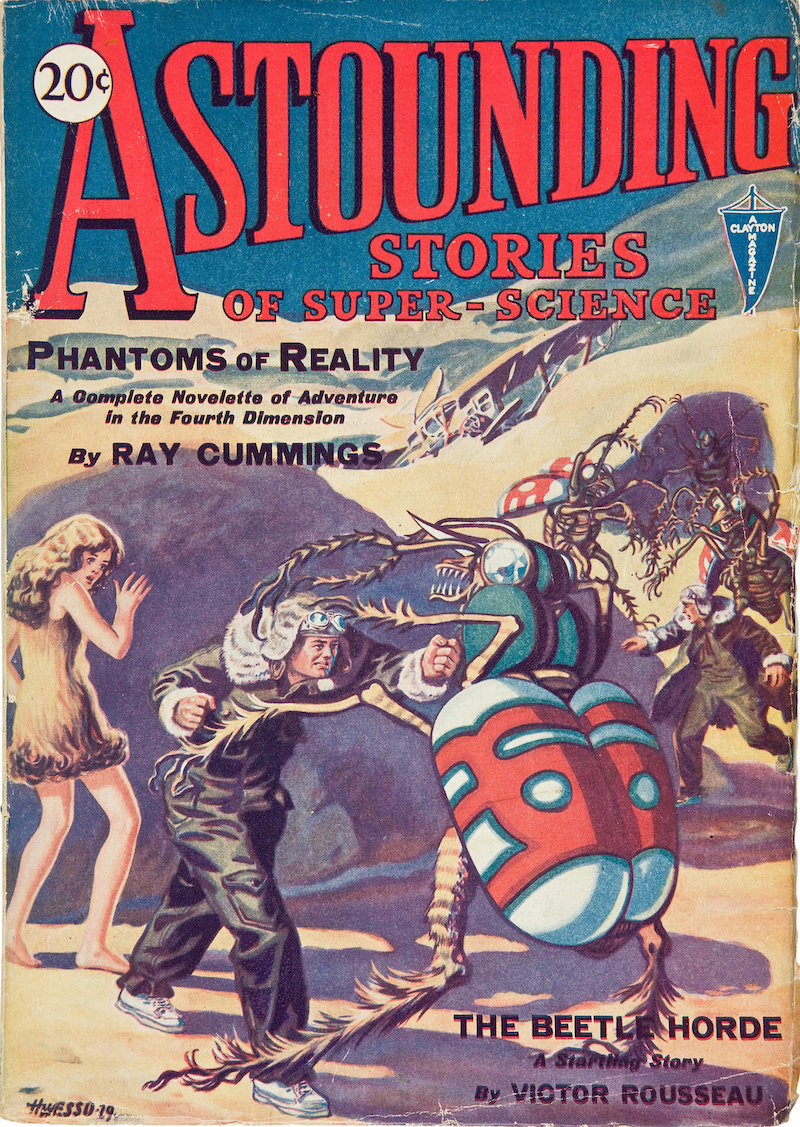

By the 1930s the newsstands were saturated with pulp magazines, but already their domination was being challenged by comic books and paperbacks. Astounding Stories of Super-Science was launched in January 1930. (The first true sf “pulp,” it has been pedantically noted, was Astounding — because Gernsback’s Amazing was not published on pulp stock. We can ignore this point.) After a rocky start, Astounding would go on to become the most influential magazine in the field within a decade.

The first incarnation of Astounding (the magazine’s name was shortened in February) was an adventure-oriented magazine. Early issues lacked much of Gernsback’s attention to the scientific and extrapolative possibilities of the sf genre, and instead featured many instances of stock pulp-adventure yarns transplanted into exotic or alien environments. While a travesty in the eyes of sf purists (in the opinion of Mike Ashley, a science fiction historian, Astounding was “destroying the ideals of science fiction”; while Gernsback’s magazines published some bad fiction, at least they had ideals — but Astounding was purely about profit), it attracted many readers.

The publisher went bankrupt in 1933, and the magazine was sold to Street & Smith. The new editor, F. Orlin Tremaine, soon made Astounding the leading magazine in pulp sf. (John W. Campbell would take over in ’37.) The stock adventure stories were replaced with what Tremaine dubbed “thought-variants” — stories that were interesting and exciting, but also explored some scientific or technological idea. PS: Along with Amazing Stories‘s “Discussions,” Astounding‘s letters section, “Brass Tacks,” also served as an important venue for communication and discussion within the emerging sf fan community.

PS: In their introduction to the 1995 anthology New Eves: Science Fiction About the Extraordinary Women of Today and Tomorrow, edited by Janrae Frank, Jean Stine & Forrest J Ackerman, the editors refer to the period between 1930 and 1950 as the era “when women were frozen out” of the sf pulps.

Copyrighted works from 1930 will enter US public domain on January 1, 2026. They will become free for all to copy, share, and build upon.

Proto-sf coinages dating to 1930, according to the Historical Dictionary of Science Fiction: AIRLOCK | FACE PLATE | GROUP MIND | MOTHER SHIP | NEEDLE-BEAM | SCOUT SHIP | SPACE FLEET | SPACE PATROL | SPACEPORT | SPACE STATION | SUB-ETHER | TIGHT-BEAM | VIEWSCREEN.

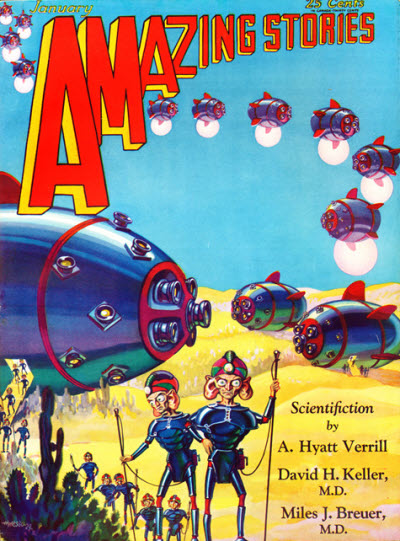

- John W. Campbell’s “When the Atoms Failed” (Amazing Stories). Contains one of the earliest depictions of computers in science fiction. A relatively straightforward piece about the discovery of atomic energy, and repelling an alien invasion. Campbell’s first published story made the cover of Amazing. Followed by five more stories during 1930; see below.

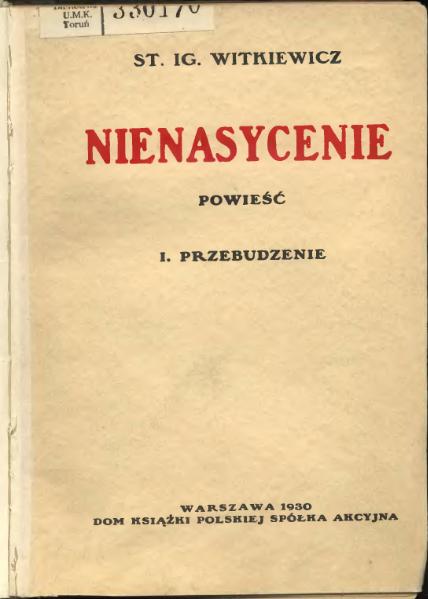

- Stanisław Ignacy Witkiewicz’s Insatiability (1930). Circa the year 2000, a Chinese army overruns Poland. In order to ensure that the occupied populace conforms contentedly to his demands — which are, more or less, those of Soviet-style communism, the Chinese leader, Murti Bing, requires Poles to take a thought-control medication: DAVAMESK B 2. Polish artists, for example, find themselves compliant with the demands of an aesthetic program that readers of the time would have recognized as Socialist Realism. (All of which predicts, uncannily, the invasion of Poland, the postwar foreign domination, and the totalitarian mind control exerted, first by the Germans, and then by the Soviet Union on Polish life and art.) The novel is also a bildungsroman; its adolescent protagonist seeks experiences: philosophical, military, sexual. His madness and eventual zombie-fication parallel what is happening to his country. An avant-garde tour de force, replete with alienation techniques; not an easy read, but a very rewarding one. Fun fact: The unnamed narrator of Insatiability is a fictionalized version of Witkiewicz himself, i.e., a thinking, feeling individual in an increasingly pacified, de-individualized society.

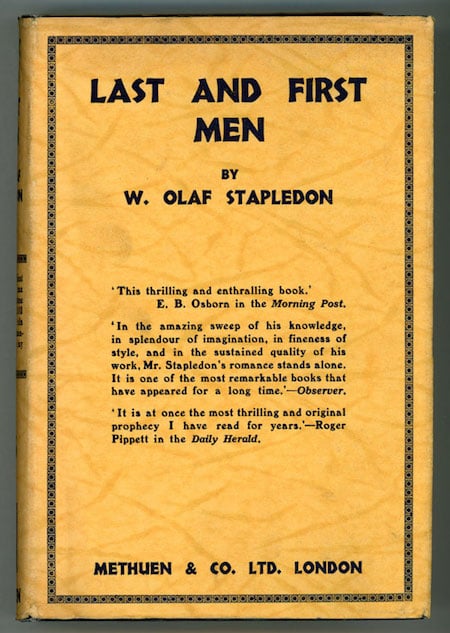

- Olaf Stapledon’s The Last and First Men (1930). In his awe-inspiring, tragicomic first novel, Stapledon ventriloquizes the future history of humankind as related to him telepathically by one of the Last Men — alien descendants of ours who will inhabit Neptune, where they’ll face extinction as the sun burns out, some two billion years hence. (Call it: psi-fi.) What does fate hold in store for us First Men? The post-WWI “passionate will for peace and a united world” won’t last long, Stapledon’s narrator informs us. Within a century aerial bombs and poison gas will have laid waste to Europe and Russia, leaving the Chinese and Americans to compete for global military-economic domination. Eventually, a World State will be founded, and peace and prosperity will reign… until Earth’s natural energy sources get used up! At that point, civilization will collapse and the First Men will devolve into superstitious savages living in the shadow of their ancestors’ skyscrapers — “though for the most part they were of course by now little more than pyramids of debris overgrown with grass and brushwood” — until, after nearly 100,000 years, they’ll re-civilize themselves and discover atomic energy. After “a bout of insane monkeying with the machinery,” all but 35 men and women, whose mutated descendants will be the Second Men, are annihilated. This sort of thing goes on, and on, for 18 generations of humankind! (Moskowitz says the book provides the bricks for the foundation of modern science fiction.)

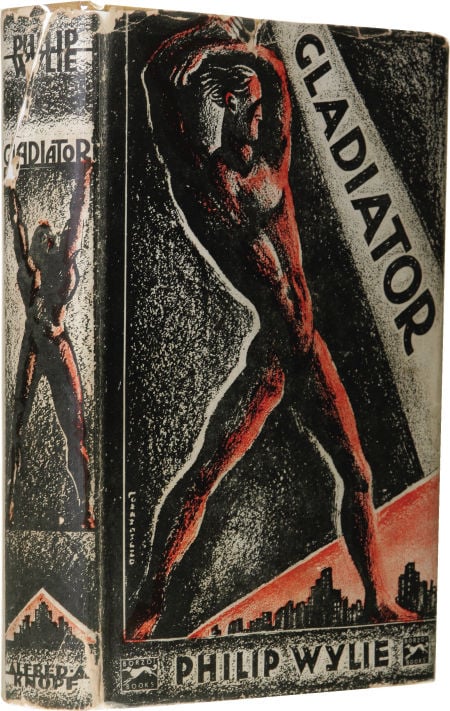

- Philip Gordon Wylie’s Gladiator (1930). Thanks to an experiment by his scientist father (who studies grasshoppers and ants), Hugo Danner is nearly invulnerable, runs faster than a train, leaps higher than trees, and hurls boulders like baseballs. His father gives him Nietzschean advice, e.g.: “The stronger, the greater, you are, the harder life is for you.” So… Hugo creates a fortress of solitude in Colorado, drops out of school, wanders the planet, then joins the French Foreign Legion at the outbreak of WWI (“He felt himself almost the Messiah of war…. He was like a being of steel”). Later, he adopts a secret identity, moves to

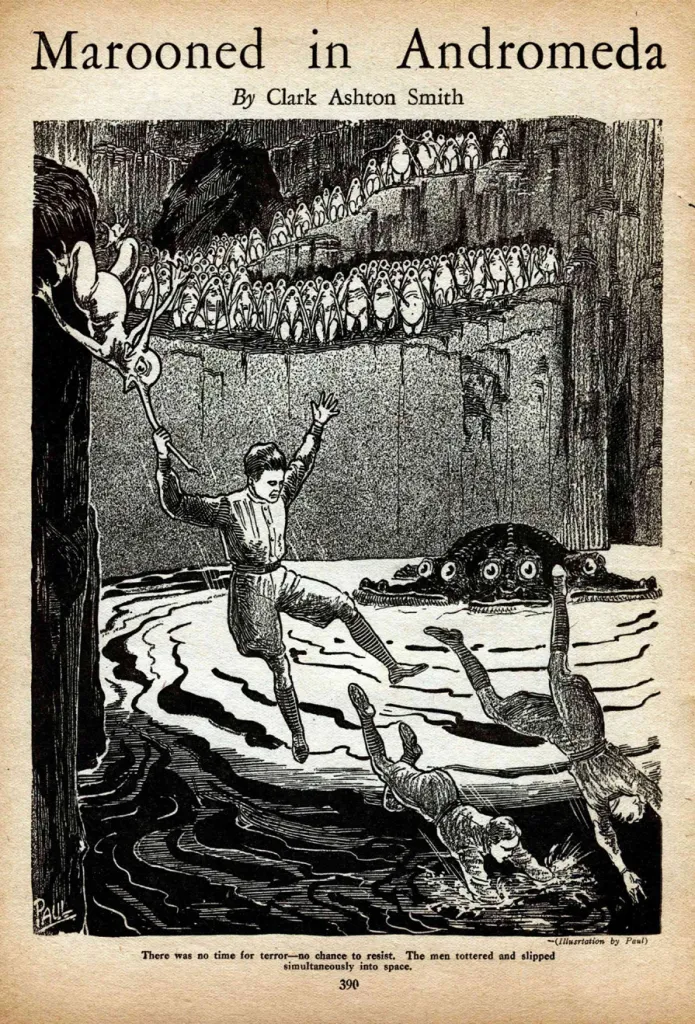

MetropolisManhattan, and vows to become “an invisible agent of right — right as best I can see it.” Despairing, however, of flawed mortals and their politics — Hugo heads to the Yucatan to start a colony of superbeings, “the new Titans.” But then he changes his mind and curses God… on a mountaintop, where he’s struck by lightning and killed. Fun fact: A major (unacknowledged) influence on Siegel and Shuster’s 1938 Superman comic. Wylie is best known as coauthor of When Worlds Collide, and as a crank(y) essayist obsessed with Soviet nukes and “Mom-ism.” - Clark Ashton Smith — almost all his work of note within the sf genre, beginning with “The Last Incantation” (June 1930 Weird Tales), was written by about 1936, when he virtually stopped creative work; almost all his later publications, and certainly the posthumous release of unknown work, come from this period.

- Clark Ashton Smith’s “Murder in the Fourth Dimension” in Amazing Detective Tales, October 1930.

- Clark Ashton Smith’s “Marooned in Andromeda” in Wonder Stories, October 1930.

- Sax Rohmer’s The Day the World Ended (1930). Three international crimefighters — Lonergan, an American secret service agent; Gaston Max, a dandified French police detective; and Brian Woodville, an English journalist — are investigating a series of strange events: radio silence in the USA, reports of man-bats in the Black Forest, the sudden death of everyone in a French village. It turns out that Anubis, a dwarfish evil genius, is plotting to establish a utopian society populated by surgically altered and highly conditioned humans. How? By destroying the rest of the Earth’s population with a sonic weapon. The trio infiltrate Anubis’s German castle, populated by 7-foot-tall guards and “soulless” houris — hello, Westworld and Stepford Wives — and call in an air strike. Fun fact: Rohmer was best known for his (Orientalist) sci-fi/horror thrillers about Dr. Fu Manchu.

- W.J. Turner’s poem Miss America: Altiora in the Sierra Nevada is of sf interest.

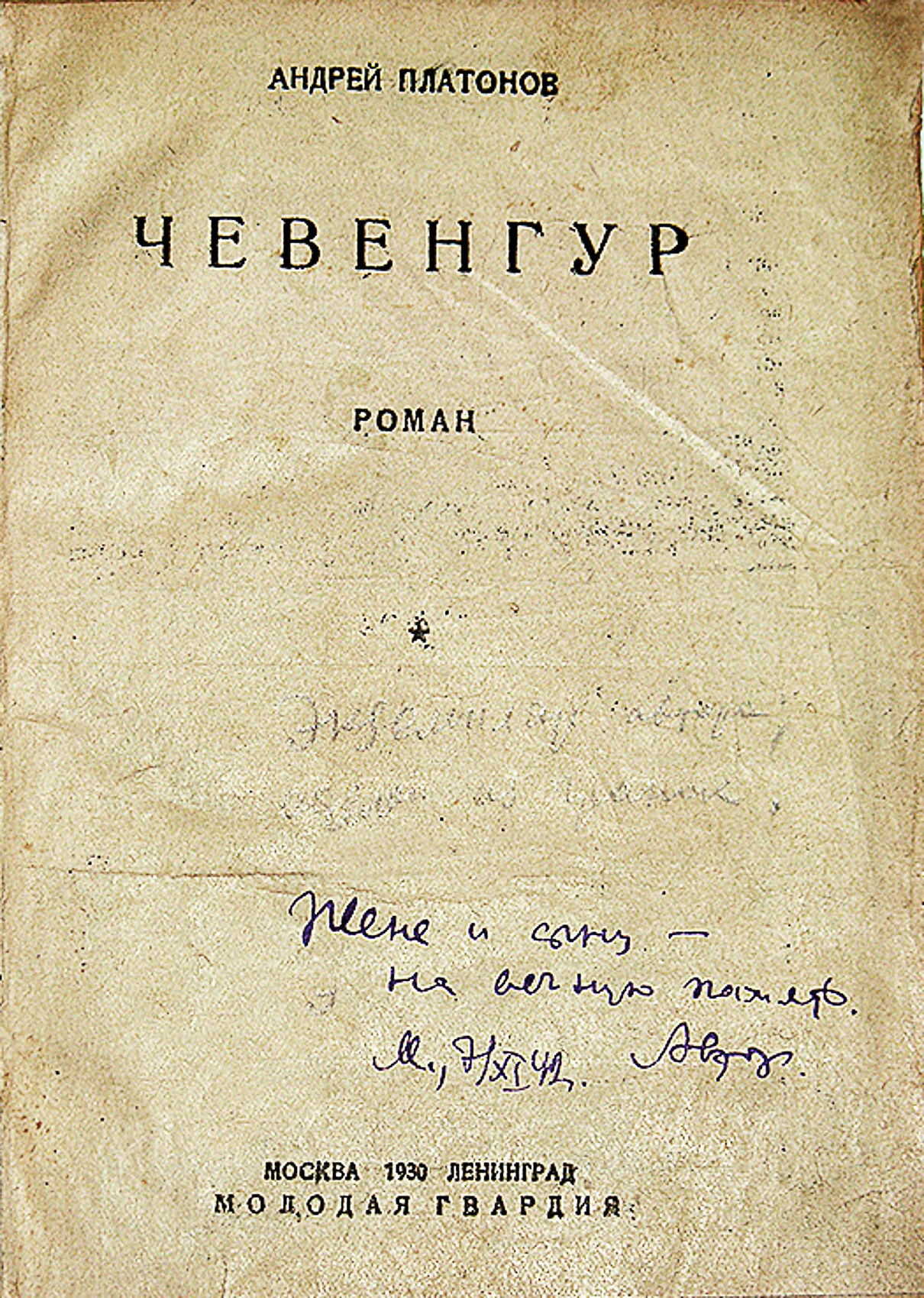

- Andrei Platonov’s Chevengur (hard to say when it was published, but I’ve seen 1930.) Dystopian novel about Bolshevik rule. Going “to look for communism among the population”, Alexander Dvanov meets Stepan Kopenkin — a wandering knight of the revolution. Kopenkin saves Dvanov from the anarchists of Mrachinsky’s gang. Our heroes find themselves in a kind of communist reserve — a town called Chevengur. Utopianist esidents of the city refuse to work, and deal cruelly with bourgeois elements. See Drozdz’s essay on “Parodies of Authority in the Soviet Anti-Utopias from 1918-1930.” There are various interpretations of the title of the novel, which, according to the feeling of its protagonist, “sounded like the enticing hum of an unknown country.” Fun facts: Although excerpts were published in the Soviet magazine Krasnaya Nov (in 1928–1929), the novel was banned in the Soviet Union until 1988. Full text of the novel was published by Ardis in 1972. It was first translated into English in 1978 by Anthony Olcott.

- Lilith Lorraine’s “The Jovian Jest.” A tale of communication with an extra-terrestrial species that us not that impressed with us. They decide to play a little trick on two of our humans.

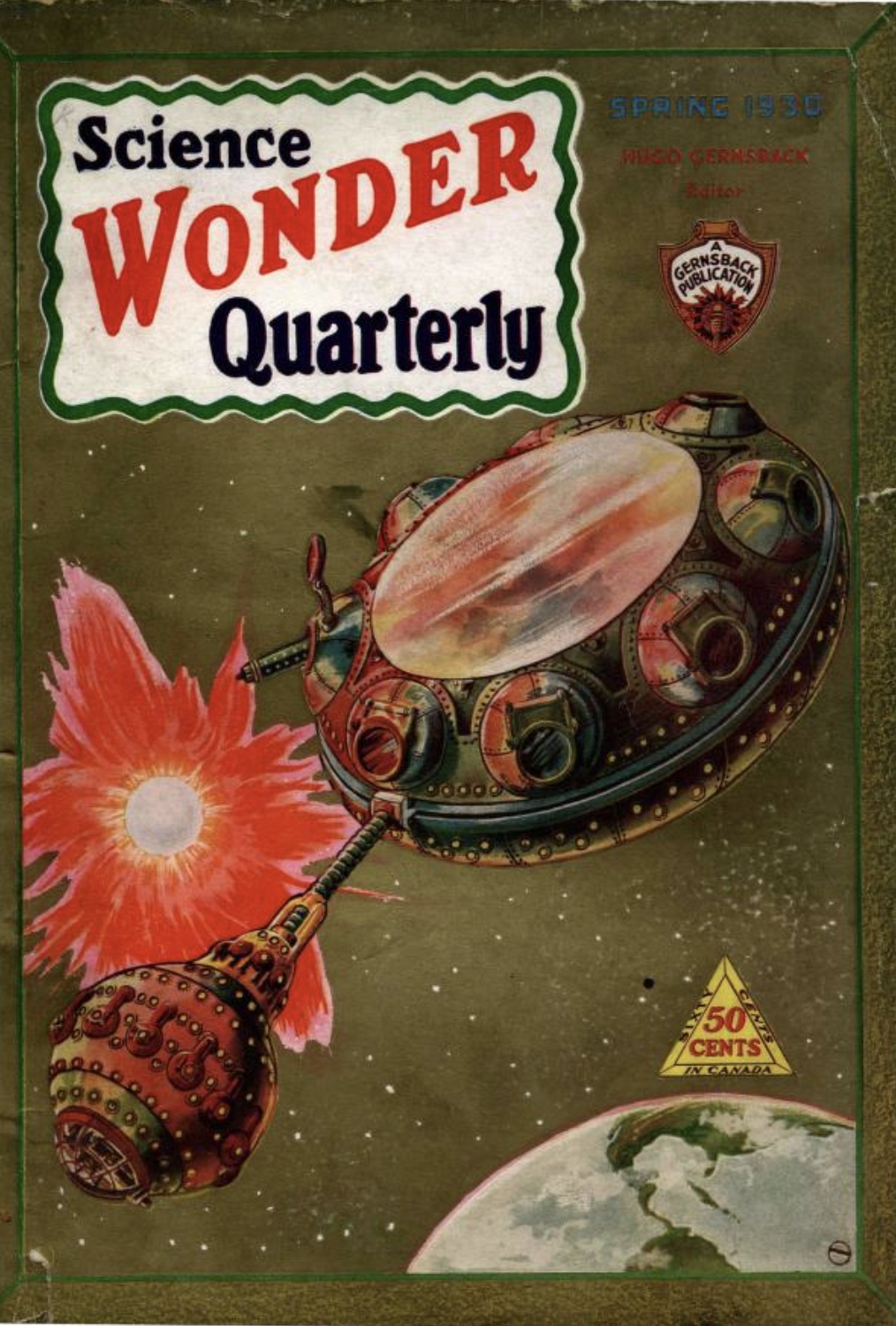

- Lilith Lorraine’s “Into the 28th Century” (Science Wonder Quarterly). A time-travel story featuring artificial wombs, eugenics, inhaled nutrition, hovercraft, and a woman as President of the United States in 1955. Donawerth notes alternative techniques of childbirth and rearing.

- Edmond Hamilton’s “The Man Who Saw the Future” (Amazing Stories). Hamilton was getting tired of the space opera theme which he had excessively exploited. This was a more original idea — according to Ashley’s Time Machines.

- Neil R. Jones’s “The Death’s Head Meteor” (in Gernsback’s Air Wonder Stories). Often described as being the first sf story to use the word “astronaut.”

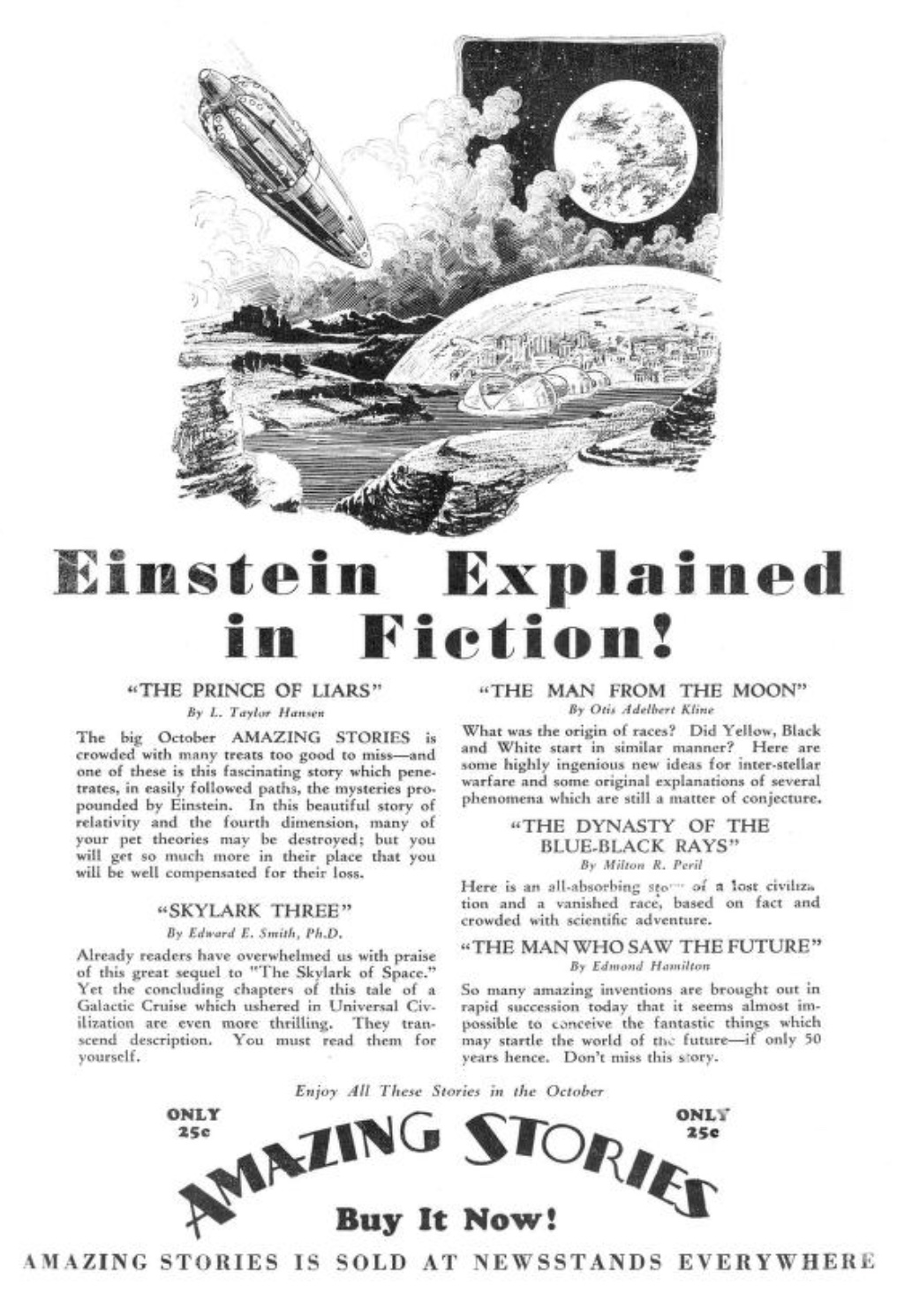

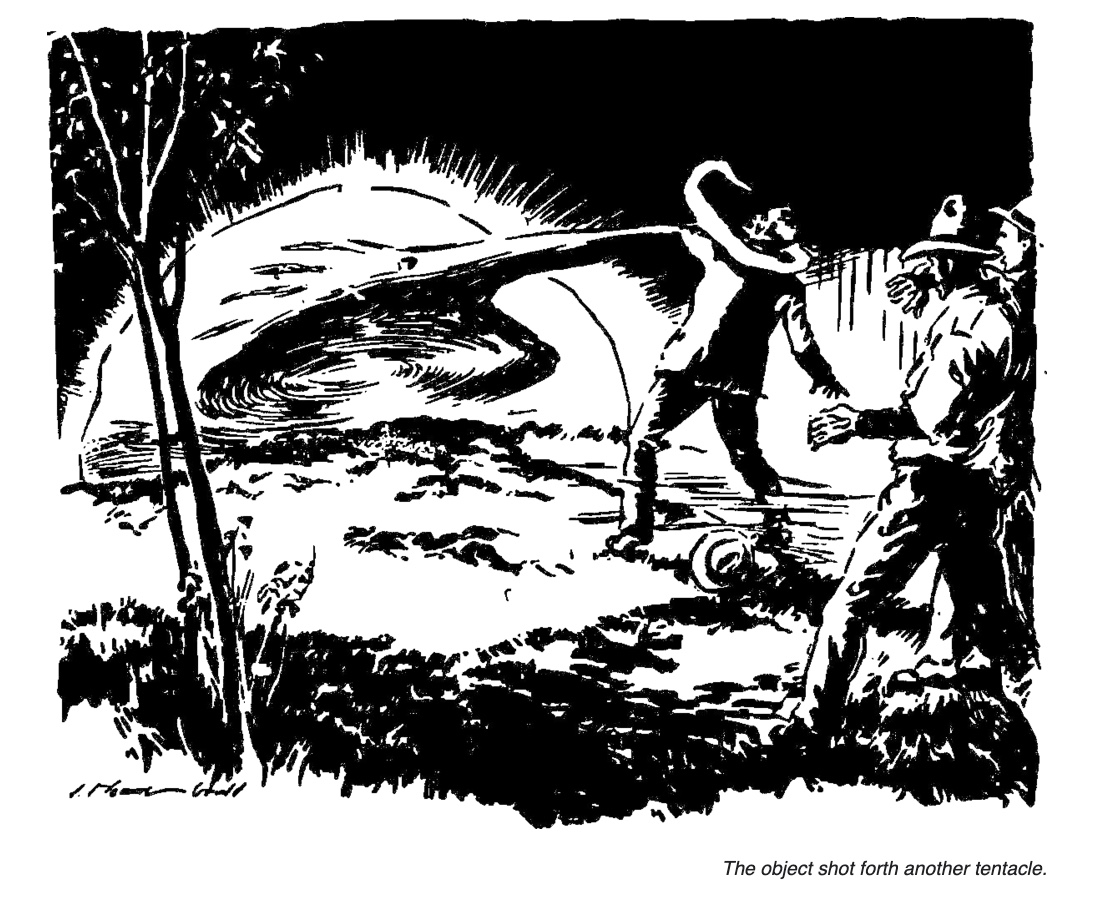

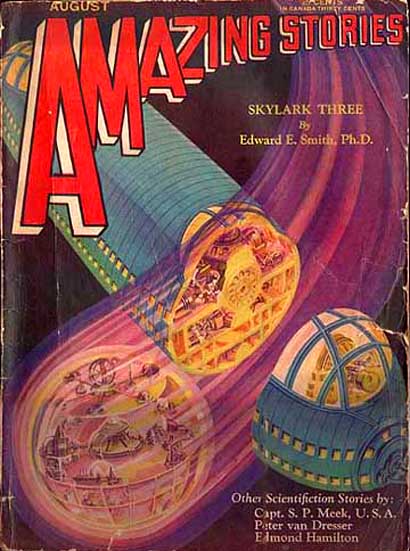

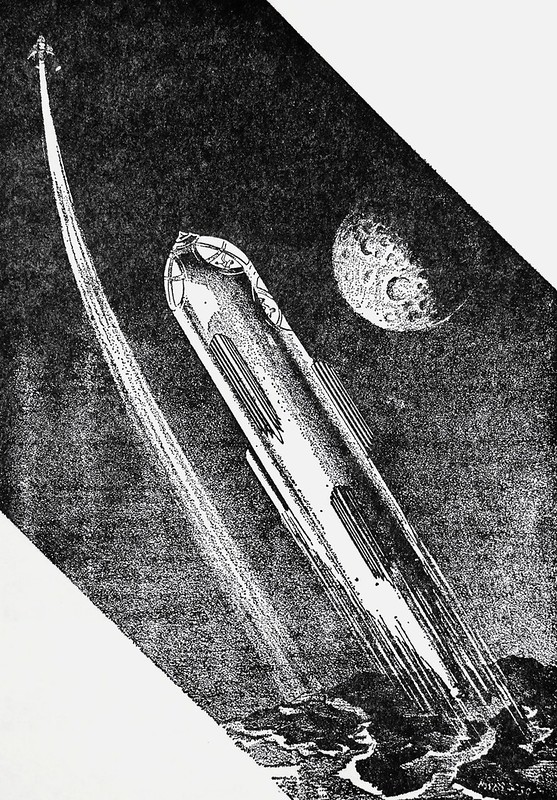

- E.E. “Doc” Smith’s Skylark Three in Aug-Sep-Oct 1930 Amazing Stories. A “super-science fiction” sequel to The Skylark of Space. Set a year after the events of The Skylark of Space, during which year antagonist Marc “Blackie” DuQuesne has used the wealth obtained in the previous book to buy a controlling interest in the story’s World Steel Corporation. When the story begins DuQuesne announces a long absence from Earth, to find another species more knowledgeable than the Osnomians allied with protagonist Richard Seaton. Shortly thereafter, DuQuesne and a henchman disappear from Earth. DuQuesne, by now aware of the Object Compass trained on him, travels far enough to break the connection, then turns toward the Green System of which Osnome is a part. Seaton discovers this, but is distracted by attempts to master a “zone of force”: essentially a spherical, immaterial shield. The Skylark Three is Seaton’s awesome new spaceship… which he uses in a genocidal attack on the natives of the planet Fenachrone, who have embarked on a mission of conquest of the entire galaxy, and eventually of the universe. Smith took space opera to new heights, according to Ashley’s Time Machines. Moskowitz in Seekers of Tomorrow calls it a better novel than the first; and says that even more than its predecessor it changed the “paraphernalia of sf.” (Arthur C. Clarke was a fan; the only space battle scene he wrote, in Earthlight, was an homage to the attack on the Mardonalian fortress in Skylark Three.)

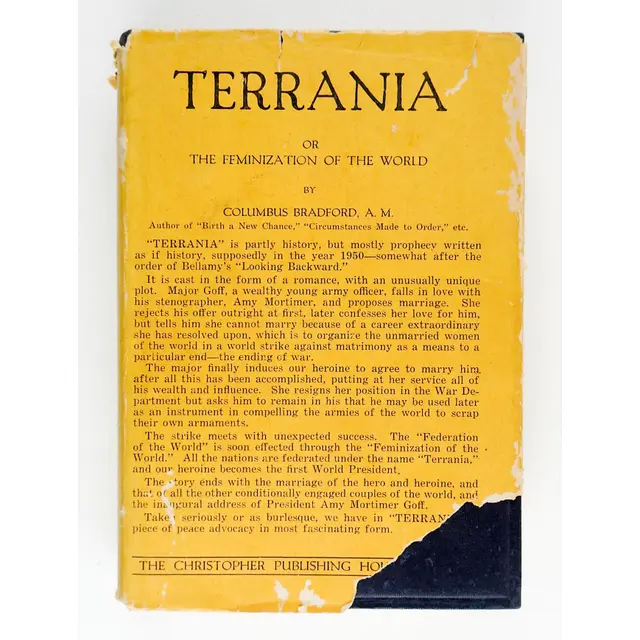

- Columbus Bradford’s Terrania, or the Feminization of the World. “The women of the world strike against matrimony and war, then form a world government headed by a woman.”

- R.F. Starzl’s “Hornets of Space.” Collected in From Off This World: Gems of Science Fiction Chosen From “Hall of Fame Classics” (1939).

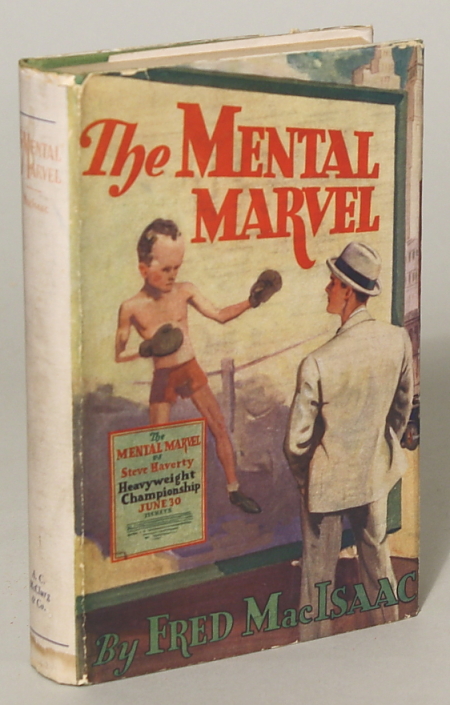

- Fred MacIsaac’s The Mental Marvel. Humorous fantasy (coded “biological science fiction” in 1978 Bleiler checklist) about a mental superman who claims he can outwit any opponent in the boxing ring, and attract any woman outside of it. “One of the better pulp writers.” – Bleiler.

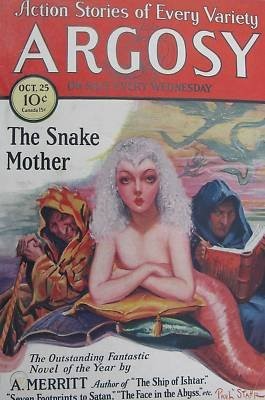

- A. Merritt’s “The Snake Mother.” The original story is better than the 1931 novel version (part of The Face in the Abyss). Fun fact: Moskowitz in Scientific Romance says that Merritt wrote what were called “different” stories.

- Slavko Batušić’s “Zbilo se čudo u gradu” (“A Miracle Happened in the City”). Batušić (1902–1979) was a Croatian writer, theater expert, lecturer, art historian and director. Although he was not an sf writer, this story is said to feature science fiction elements.

- August Cesarec’s “San doktora Prospera Lupusa” (“The Dream of Doctor Prosper Lupus”). Romanian. Cesarec (1893 – 1941) was a Croatian writer and communist activist. He was executed by the Ustaše — a Croatian fascist and ultranationalist organization.

- Berilo Neves’s collections A costela de Adão (Adam’s Rib), and also A mulher e o diabo (The Woman and the Devil, 1931) and Século XXI (21st Century, 1934). Light, amusing, sf short stories by Brazilian journalist and writer Berilo Neves (1901-1974). Achieved an unprecedented success among readers. They feature interplanetary tourism, eccentric scientists, extraordinary machines and drugs, always with a view to generating comic situations. The sf elements serve only to precipitate situations involving jealousy, amorous conquests and infidelities.

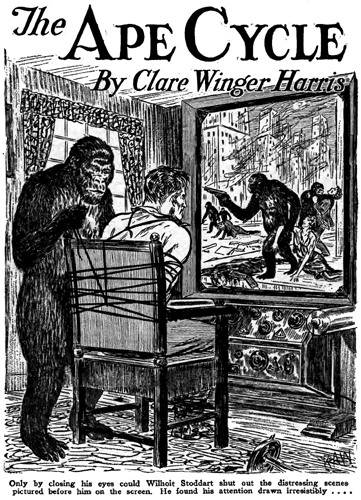

- Clare Winger Harris’s “The Ape Cycle.” Her final and longest, story, which has a strong similarity to the background for Pierre Boulle’s Planet of the Apes, published more than thirty years later. In Harris’s story, Daniel Stoddart and his son Ray begin the process of uplifting apes for use as servants. The story follows their family for several generations as they successfully breed the animals, introduce them to society, and society changes based on the apes’ abilities and usefulness. Throughout, Harris includes some speculation about whether animals can have souls and at what point using the uplifted animals would amount to slavery, although she never quite provides an answer to either question, eventually turning her attention to an uprising by the creatures. Female airplane pilot and mechanic. PS: Info on the author here.

- David H. Keller’s The Evening Star (April-May 1930 Wonder Stories). In the sequel to the Conquerors, Venus turns out to be dominated by radiant human masters, and the utopia they inhabit is invulnerable to the tiny invaders, who are now suffering a very sudden devolution.

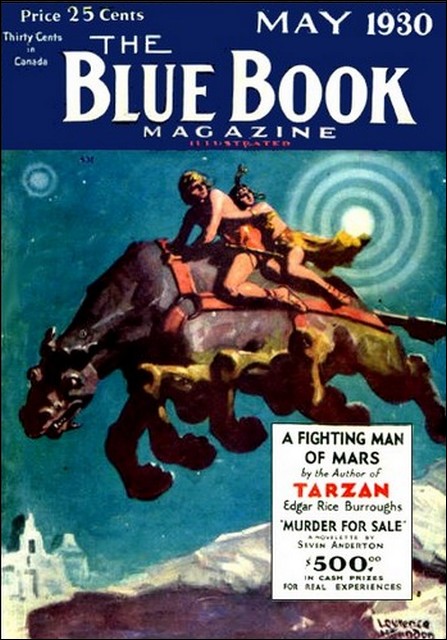

- Edgar Rice Burroughs’s A Fighting Man of Mars. Published in The Blue Book Magazine as a six-part serial in the issues for April to September 1930. It was later published as a complete novel by Metropolitan in May 1931. More cool covers here.

- Edmond Hamilton’s “The Universe Wreckers” — space opera.

- Erle Stanley Gardner’s A Year in A Day. Transplants Wells’s “New Accelerator” into a crime story. Not very good, I’ve heard. But interesting that ESG dabbled in sf.

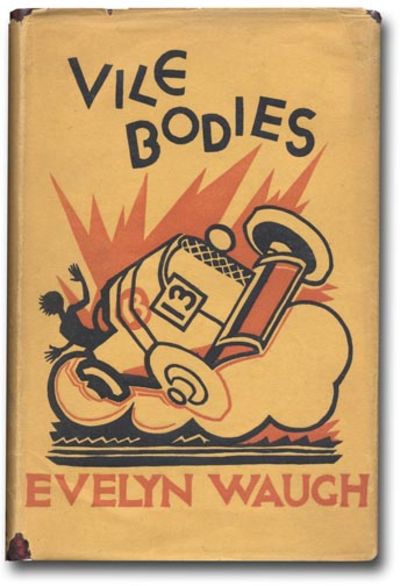

- Evelyn Waugh’s Vile Bodies. The author’s second novel, set in the near future — his only forway into sf. It satirizes the “bright young things” — the rich young people partying in London after World War I, and the press which fed on their doings. Ends in an apocalyptic Europe torn by a final War – but this is no more than a sardonic flourish for a brief closing chapter titled “Happy Ending”. Heavily influenced by the cinema and by the disjointed style of T. S. Eliot, this is Waugh’s most ostentatiously “modern” novel. Fragments of dialogue and rapid scene changes are held together by the dry, almost perversely unflappable narrator. Waugh said it was the first novel in which much of the dialogue takes place on the telephone. At the end, there is a brief apocalyptic war scene in which the protagonist, Adam Fenwick-Symes, reflects on the use of the new leprosy-spreading “Huxdane-Halley” [name-checking J.B.S. Haldane and… maybe Aldous’s brother Julian Huxley?] bomb.

- Jack Williamson’s “The Cosmic Express” — appears in the 1980 anthology Science Fiction: The Best of Yesterday.

- Francis Flagg’s “An Adventure in Time.” Mentioned in John Cheng. Matriarchal future. Cautionary tale about the virtue of gender roles. Professor Bayers explains how he went into the future. Flagg uses an idea that not many have since, futurians sending a working model back in time so present day people can discover how to build the machine. Once built, he goes to a utopia ruled by women. Bayers falls in with a group of males, all bred for small size and low numbers, who want to rebel against the women. The rebellion quickly falls apart when Bayers meets Editha. Flagg (pseudonym of Canadian-born author Henry George Weiss) was a discovery of Gernsback’s. Some of his later work was written in collaboration with Forrest J Ackerman.

- Harl Vincent’s “Gray Denim.” (Astounding Stories, December 1930.) Dystopian — part of the Purple and Gray trilogy of stories.

- Paul Ernst’s The Black Monarch (1930). In 1992, Dr. Sanderson, foster-son of an inventor who’s created a machine that can respond to thought waves, detects the presence of an immensely evil being in Algeria. So Sanderson and an adventurer, Neil Emory, explore — and discover a subterranean civilization beneath that country. The underground land is ruled by Rez, an immortal ancient Egyptian — whose brain is so enlarged that he’s replaced his own skull with a metal contraption. Rez has highly developed paranormal powers; he converses telepathically, and, with the aid of a huge diamond crystal, controls the wills of his small, robot-like subjects. From his underground lair he’s manipulating the world into a war that will smash civilization. Fun fact: From 1939-42, under the syndicate name Kenneth Robeson, Ernst would write the original 24 Avenger stories for the magazine of that title.

- Henri-Jacques Proumen’s Le sceptre est volé aux hommes (“The Sceptre is Stolen from the People”). Walloon/Belgian story about a race of mutants who enslave the population of a Pacific island.

- Jean de La Hire’s Le pays inconnu, Les Amazones, and Le mystère vaincu are the first three in the Amazons series. All published 1930. Late works by Adolphe d’Espie (1878-1956) who began his prolific career before 1900. Also in 1930: Jean de La Hire’s L’île d’épouvante.

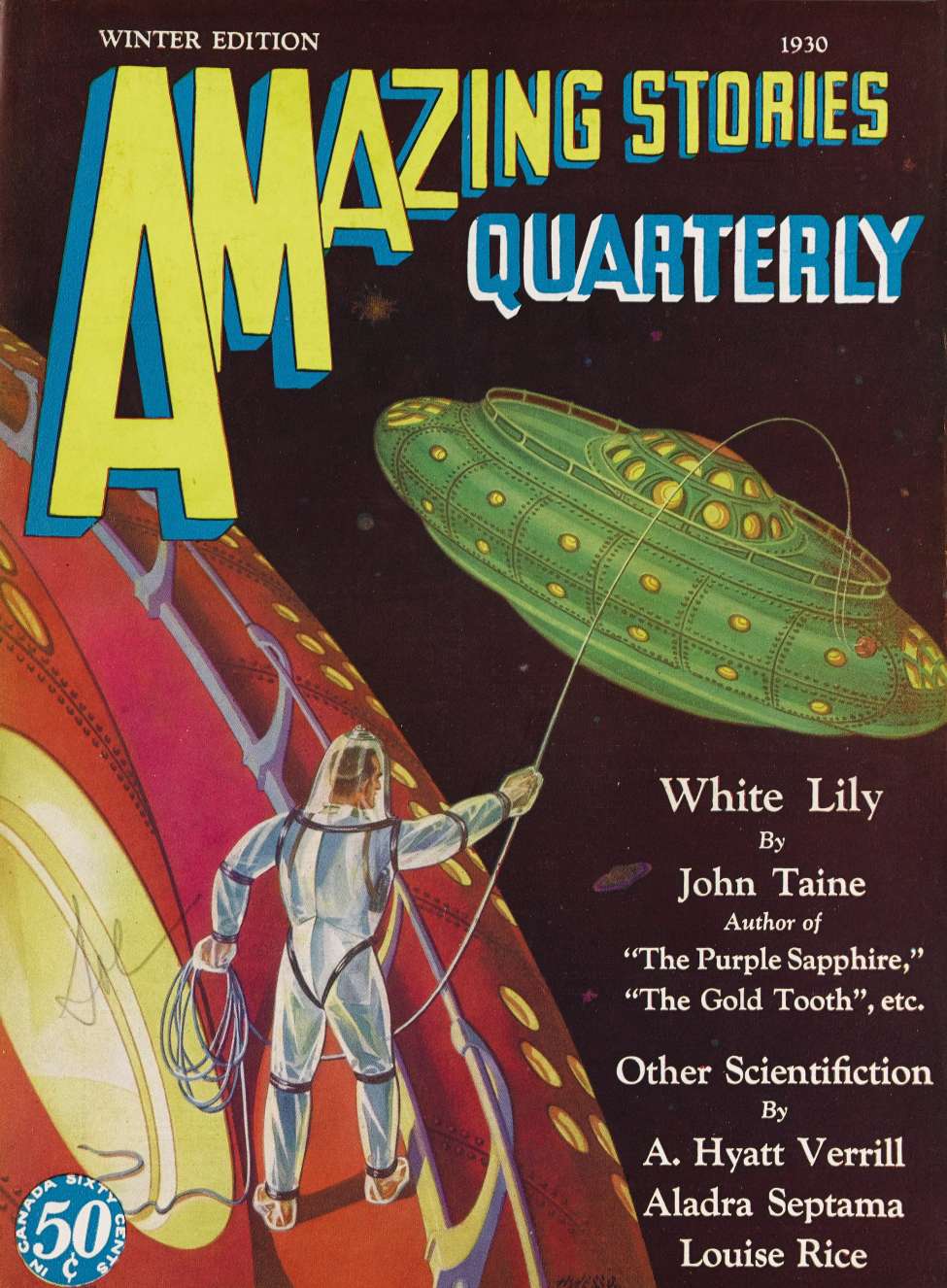

- John Taine’s The White Lily (later as The Crystal Horde). Silicate life threatens life on earth. Extravagant. The 1952 novel version is substantially rewritten from a version that originally appeared in the magazine Amazing Stories Quarterly in 1930. Groff Conklin, reviewing the 1952 edition, gave a mixed opinion; praising “one of the most magnificent science-horror ideas ever created,” but ridiculing the plot as “probably the worst yellow-menace-plus-Bolsheviks-plus-religious-prejudice melange ever to hit science fiction.” Boucher and McComas similarly found the novel an unsuccessful fusion of disparate elements, “a dull and involved story of Chinese warfare” and “some amusing satire and a dazzling series of descriptions.” P. Schuyler Miller, however, praised the story as among Taine’s best, saying “the wildest of fancy, liberally laid on a solid scientific core.” Bleiler reported that the opening sections regarding the outbreak of crystal life “have a certain fascination, despite the horrible writing,” but the rest of the novel “is a jumble that never achieves conviction.”

- John Taine’s The Iron Star. Mutation, devolution. The novel concerns an African expedition. Swain, a member of the expedition, becomes demented and attempts to exterminate a peculiar species of African ape. The other members of the expedition are befriended by an intelligent ape called the Captain. The expedition discovers that the apes are in fact humans that have evolved in reverse due to exposure to a meteor and that the Captain was once human. P. Schuyler Miller rated the novel as “Taine’s greatest book, and one of the greatest in all science fiction”; he praised its “daring scientific concept” and its “perplexing mystery,” as well as “a smoothness which none of [Taine’s] other books quite show.” Everett F. Bleiler reported: “The idea is interesting, despite Taine’s ignorance of zoology and his shocking racial intolerance,” but “the literary development is fumbling.” Listed in the Cambridge Companion to SF chronology, and the Science Fiction After 1900 timeline.

- John W. Campbell’s “Piracy Preferred” (in Amazing Stories). This is the first-published in the author’s Arcot, Morey and Wade series. Wade is a super scientist with an invisible spaceship; he is a pirate until thwarted by physicist Richard Arcot, mathematician William Morey, and design engineer John Fuller (Campbell’s projection of himself according to Ashley’s Time Machines). The other stories from 1930 are “The Black Star Passes” (in Amazing Stories Quarterly) and “Solarite” (in Amazing Stories). The heroes face a succession of battles of ever-increasing size fought with a succession of wonderful weapons of ever-decreasing likelihood. The stories were put into book form as The Black Star Passes (1953); these and other Arcot, Morey and Wade stories were assembled as A John W. Campbell Anthology (1973). Galaxy reviewer Groff Conklin described the stories as “three creaking classics… fun to read, [but] rococo antiques [without] believable characters, human relations, even logical plots.” Boucher and McComas dismissed the book as “a hopelessly outdated set of novelettes… of concern only to those who wish to observe the awkward larval stage of a major figure in science fiction.”

- Kathleen Ludwick’s “Dr. Immortelle” (Amazing Stories Quarterly, same Fall issue as “The Black Star Passes.”). A vampire story but with a scientific angle. The Cambridge History of Science Fiction notes this story as an example of how women writers of the Golden Age used multiple narrators to question the authority of the male scientist point of view. Here there are three points of view, one within the other (as in Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein). The story begins and ends with an engineer who loved Linnie, the nurse who exposes the terrible actions of Dr. Immortelle, a mad scientist who steals blood from young children for transfusion so he can remain young. The body of the story is told by Dr. Immortelle’s former slave, who also loves Linnie, and has been the subject of Dr. Immortelle’s experiments, in the process transformed from black slave to white assistant by transfusions from white children. And within his story, Linnie has a voice, although only an intermittent one. The multiple narrators, however, resist the pull of the single scientist narrator (Dr. Immortelle’s point of view does not shape the story), and the nurse’s voice also resists the picture of her we derive from the male narrators. The engineer, who in the traditional sf plot would have gained Linnie as his prize, sees Linnie as “the ideal nurse” full of “beauty and womanly grace.” Linnie, however, is the voice of moral strength, castigating Dr. Immortelle for leaving the scene of a car accident, and accosting him when she recognizes him as the murderer of her little brother years before. Neither prize nor ideal, she dies in a Red Cross tent on a battlefield in World War I, a woman who has escaped the usual role of women in sf stories of the period.

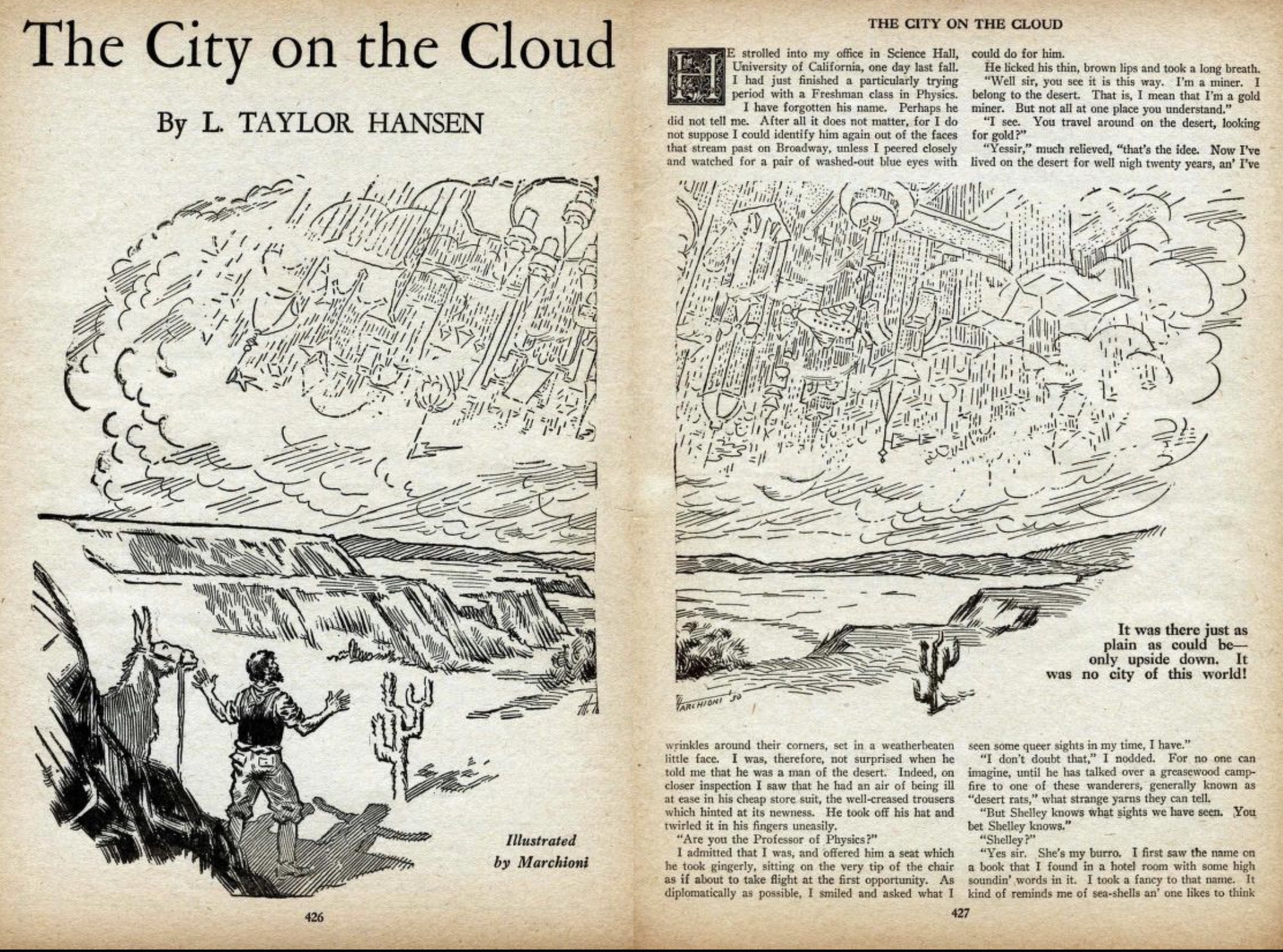

- L. Taylor Hansen (Lucile Taylor Hansen)’s “The City on the Cloud” (Wonder Stories, October 1930). Donawerth notes allusion to Frankenstein. See this list of Pre-1950 Utopias and Science Fiction by Women.

- L. Taylor Hansen (Lucile Taylor Hansen)’s “The Man from Space” (Amazing Stories, February 1930). See this list of Pre-1950 Utopias and Science Fiction by Women.

- L. Taylor Hansen (Lucile Taylor Hansen)’s “The Prince of Liars” (October 1930 Amazing). Perhaps the most interesting of her works. The story’s protagonist is an emissary from the planet of Allos, whose telepathic inhabitants are masters of antigravity. He appears on Earth at wide intervals to obtain data on scientific advances without seeming to age, his apparent time travel being due to time distortion, as time moves very much more slowly on Allos.

- Leslie F. Stone’s “Women with Wings.” Second in the Mentor series. A woman’s view of war between the wars. Race and racial breeding. Sequel to “Men with Wings”; see 1929. Donawerth notes alternative techniques of childbirth and rearing.

- Leslie F. Stone’s “Through the Veil.” Amazing Stories, May 1930. A story of the fourth dimension and Irish folklore. See this list of Pre-1950 Utopias and Science Fiction by Women.

- Pansy Black’s he Valley of the Great Ray. Published by Gernsback. See this list of Pre-1950 Utopias and Science Fiction by Women.

- Merab Eberle’s “The Mordant.” (Amazing Stories, March 1930). See this list of Pre-1950 Utopias and Science Fiction by Women.

- Merab Eberle’s The Thought Translator. Published by Gernsback. See this list of Pre-1950 Utopias and Science Fiction by Women.

- Louise Rice and Tonjoroff-Roberts’s “The Astounding Enemy” (in Amazing Stories Quarterly). See Donawerth – a female scientist. Same issue as John Taine’s White Lily. See this list of Pre-1950 Utopias and Science Fiction by Women.

- Minna Irving’s “The Man from Space” (Amazing Stories, February 1930). See this list of Pre-1950 Utopias and Science Fiction by Women.

- M.F. Rupert’s “Via the Hewitt Ray” (Science Wonder Quarterly, Spring 1930; same issue as Clare Winger Harris’s “The Ape Cycle.”). Mentioned in Moskowitz collection When Women Rule. MF Rupert was a woman, and I think this is her only story. A female scientist discovers a dimension where highly evolved women have more or less done away with men. Republished in 2015 by Mike Ashley in The Feminine Future: Early Science Fiction by Women Writers. See this list of Pre-1950 Utopias and Science Fiction by Women.

- Menotti del Picchia’s A República 3.000 (“The Republic 3000”). Brazilian adventure novel featuring a futuristic lost city; also published as A filha do inca “Daughter of the Inca”).

- Miles J. Breuer’s “The Gostak and the Doshes” (Amazing Stories, March 1930). Story about Einstein’s theory of relativity, and the power of propaganda. Anti-war stories like this one were in a tiny minority until the outbreak of war in Europe in 1939 helped encourage a new seriousness, most conscientiously displayed in John W Campbell Jr’s Astounding. Fun fact: The whole thing seems to have been inspired by a statement in the 1923 book The Meaning of Meaning: “Let the reader suppose that somebody states: ‘The gostok distims the doshes.’ You do not know what this means, nor do I.” Collected in the odd and interesting anthology Science Fiction: Stories and Contexts (2008, ed. Heather Masri).

- Murray Leinster’s Murder Madness (May-August 1930 Astounding; 1931 in book form). Though featuring a mad scientist who wishes to rule the world through the use of a deadly drug, Leinster’s first novel was not titled so as to address any sf market, and is presented as a mystery adventure, It is, however, certainly sf.

- Neil Bell’s The Seventh Bowl. His first sf novel, as by ‘Miles’. (Reissued in 1934 under his own name.) Begins the short Gas War sequence. It is a bitter future history in which the deployment of a technology of immortality by corrupt politicians sets in train a chain of events leading to the Gas War of 1940 and to the world state which follows. The invention of an immortality drug corrupts government leaders, who create eugenics laws to enforce their rule; but the development of a new power source causes the end of the world.

- Rudyard Kipling’s “Unprofessional.” His final sf story; it appeared in the October 1930 Saturday Review of Literature. Suggests that planetary “tides” may affect human tissue.

- M(ary) Saltoun’s After. See this list of Pre-1950 Utopias and Science Fiction by Women.

- I[nga] M. Stephens’s “The Pineal Stimulator” (Amazing Stories, November 1930). See this list of Pre-1950 Utopias and Science Fiction by Women.

- Aelfrida Tillyard’s Concrete. See this list of Pre-1950 Utopias and Science Fiction by Women.

- Lionel Britton’s Brain. Expressionist symbolic drama about the development of artificial intelligence, perhaps intended in part as a leftist allegory. A utopian bildungsroman whose main focus is the life of an idea in society. The time ranges from the presumable present to about fifty million years or more in the future. The play is broken into short scenes; all characters are symbolic figures. Begins with a long argument between a man of science and a librarian (who represents emotion and stupidity) about the possibility of building a mechanical brain to unite the human race. Years later, a gigantic mechanical brain is in fact constructed in the Sahara. The work is accomplished by the Brain Brotherhood, a private organization of scientists. The next scenes are set much further into the future. Brain now controls every aspect of human life — mating, vacations, and even death. Brain no longer needs human assistants, is autonomous, and has expanded. Eventually a “dark star” destroys Earth and the Brain. “Perhaps I underestimate the play when I call it a bore.” — Bleiler. The same author also gave us Hunger and Love (1931), with an introduction by Bertrand Russell, and Space-Time Inn (1932).

- Sophie Wenzel Ellis’s “Creatures of the Light” (Astounding Stories of Super-Science February 1930). Donawerth notes alternative techniques of childbirth and rearing. Republished in 2015 by Mike Ashley in The Feminine Future: Early Science Fiction by Women Writers. See this list of Pre-1950 Utopias and Science Fiction by Women.

- Sophie Wenzel Ellis’s “Slaves of the Dust” (Astounding Stories of Super-Science December 1930). See this list of Pre-1950 Utopias and Science Fiction by Women.

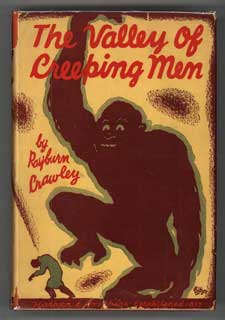

- Rayburn Crawley (pseudonym of US authors Laura Spencer Portor Pope and Dorothy Giles)’s The Valley of Creeping Men. Mystery adventure novel in which Ned Shackleton travels to a hidden African valley in search of the secret chemical formulas and maps of a murdered scientist and a gorilla-man, “The Yellow One,” the subject of the scientist’s experiments, who disappeared when his captor was killed. The trail leads complicatedly to Africa, where a Lost World is discovered, though it is inhabited now only by upright black apes. The ultimate function of the yellow ape itself (or himself) is never fully articulated, though the discovery of a world-changing chemical may be implicated. The second installment in the Yellow Ape sequence is Chattering Gods (1931).

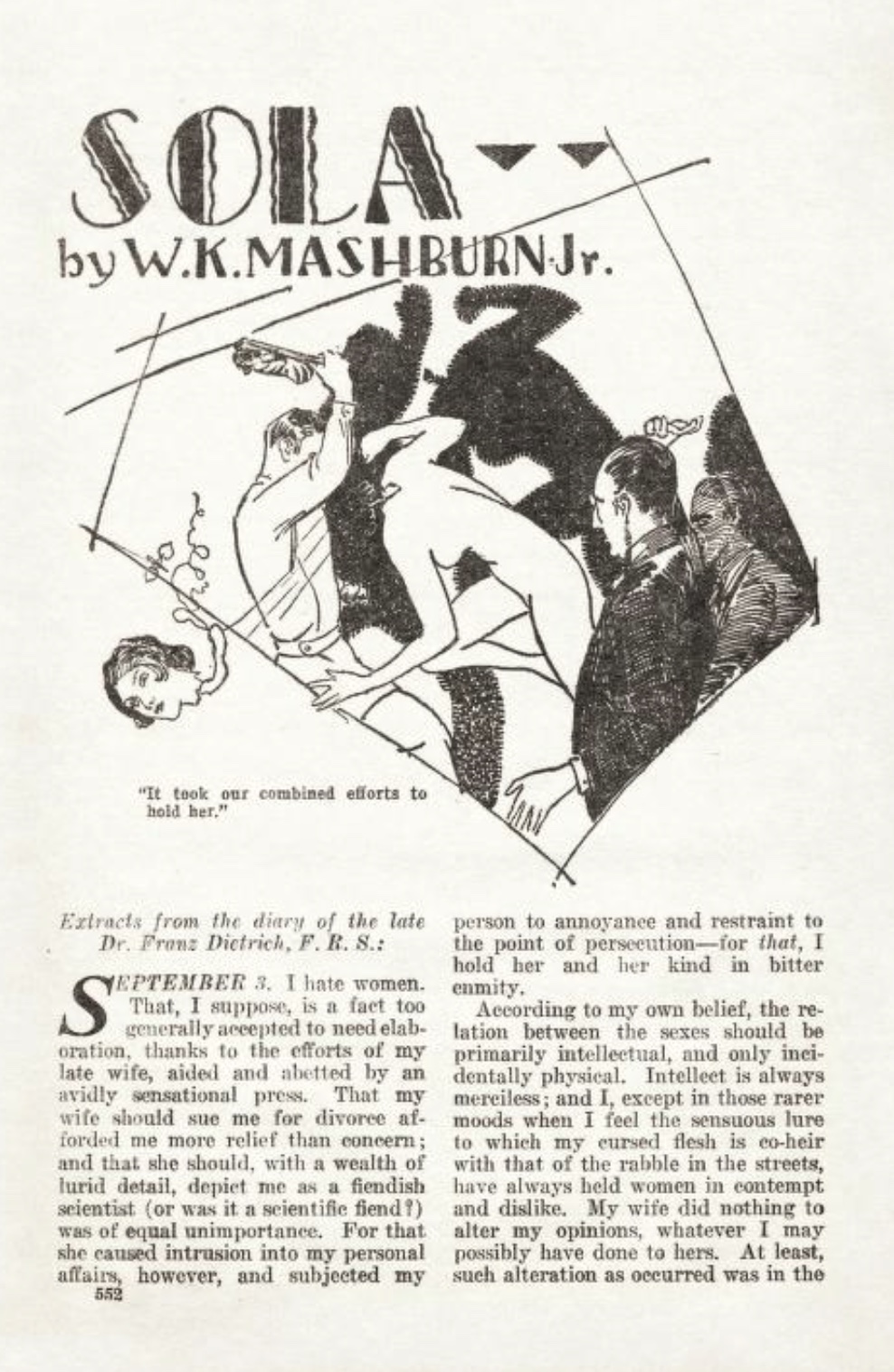

- W.K. Mashburn’s “Sola” (Weird Tales, April 1930). Though he despises women and can’t stand their company, Dr. Franz Dietrich desires them sexually. So he invents a flesh-like substance, which a sculptor helps him shape into a gorgeous female android. Having wired Sola with complex responses — the apparatus is supposed to react in particular ways, immediately upon perceiving his telepathically projected emotions — the mad scientist invites a group of colleagues over to dinner. Growing tipsy, Dietrich flies into an embarrassed fury, because he thinks Sola is unresponsive, and tries to destroy it. But his colleagues — and eventually, the entire town — pitch in to raise his self-esteem by treating Sola as a member of the community. Oh wait, I’m thinking of Lars and the Real Girl. What actually happens is that Sola’s emotion receptors are activated by the professor’s rage, and his own creation crushes him to death. A classic example of what McLuhan — in The Mechanical Bride (1951) — would call “the curious fusion of sex, technology, and death.”

- Amelia Reynolds Long’s The Mechanical Man. Published by Gernsback. See this list of Pre-1950 Utopias and Science Fiction by Women.

- Kathleen Ludwick’s “Dr. Imortelle” (Amazing Stories Quarterly, Fall 1930). See this list of Pre-1950 Utopias and Science Fiction by Women.

- Ruth Vassos’s Ultimo. See this list of Pre-1950 Utopias and Science Fiction by Women.

ALSO: Debye uses x-rays to investigate molecular structure; Eddington attempts to unify general relativity and the quantum theory. Pluto discovered. Freud’s Civilization and its Discontents, Dirac’s Principles of Quantum Mechanics. Ras Tafari becomes Emperor Haile Selassie of Ethiopia. Hart Crane’s “The Bridge,” T.S. Eliot’s “Ash Wednesday,” Faulkner’s As I Lay Dying, Evelyn Waugh’s Vile Bodies, Robert Musil’s The Man Without Qualities (1930-1942). Dashiell Hammett’s The Maltese Falcon, Arthur Ransome’s Swallows and Amazons, Max Brand’s Destry Rides Again (1930), Charles Williams’s fantasy adventure War in Heaven, Carolyn Keene’s Nancy Drew adventure The Secret of the Old Clock, Hergé’s Tintin in the Land of the Soviets. The Marlene Dietrich movie Blue Angel. Mickey Mouse appears as a newspaper comic strip; the first published example of Disney comics.

Michael Roberts’s first collection of poems, These Our Matins. Rich use of scientific language. Roberts studied chemistry and mathematics. “Rocks are Immutable” makes reference to the electron, to chlorophyll, and to the gamete. “Schneider Cup” brings in the asymptotic curve. “The Goldfish” suggests Einsteinian cosmological questions. The later poem “Sirius B” takes as its central image a white dwarf dtar from whose gravitational pull light cannot escape.

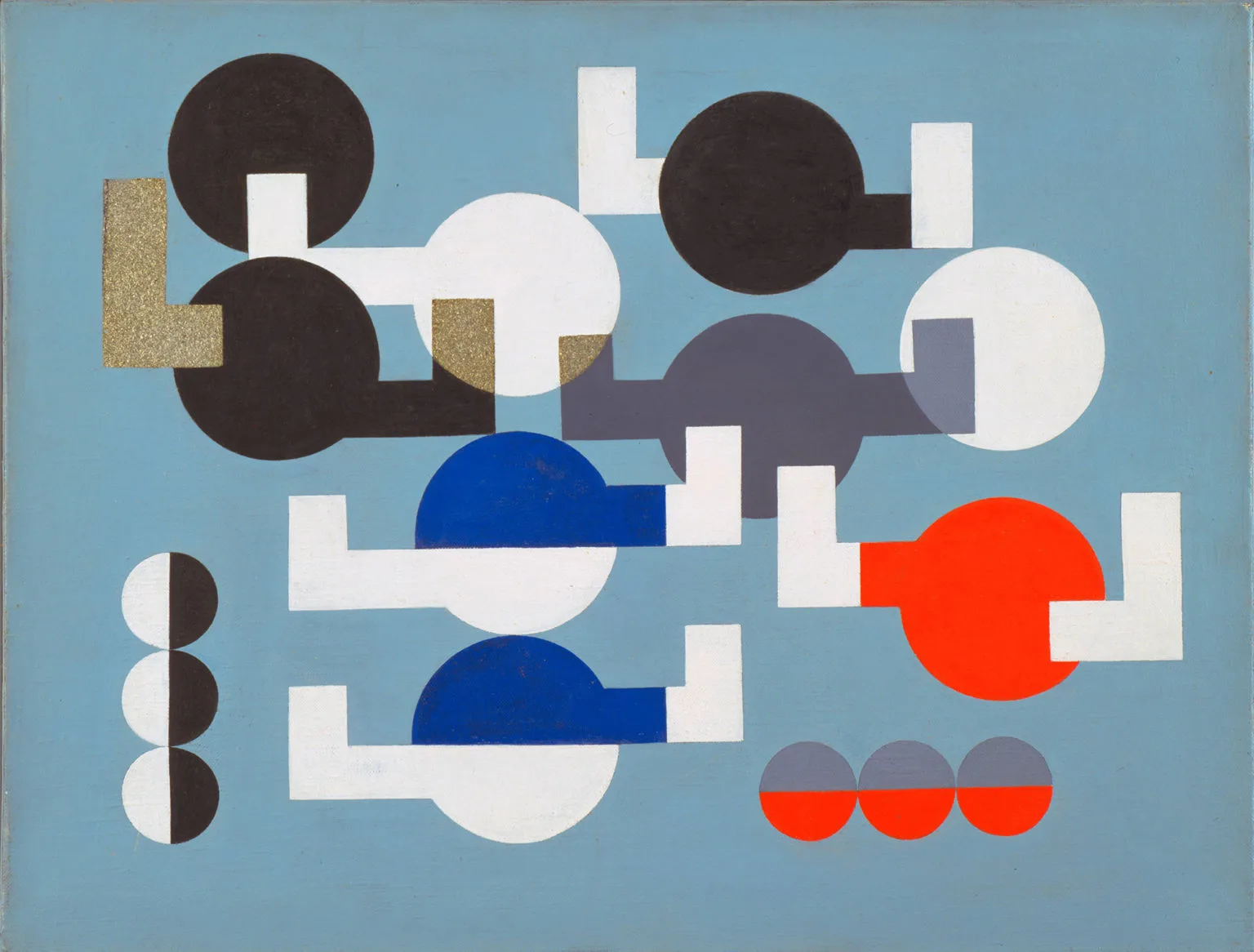

The principles of textile work—pattern, senses of proportion, the rationality of line—became the basis of Sophie Taeuber-Arp’s practice. Unlike her contemporaries Piet Mondrian and Wassily Kandinsky (whom she later counted as a friend), whose practices were guided by utopian values and spiritual concerns, Taeuber-Arp was simply interested by the interplay of geometry and color, and its potential to beautify everyday life.

MORE RADIUM AGE SCI FI ON HILOBROW: HiLoBooks homepage! | What is Radium Age science fiction? |Radium Age 100: 100 Best Science Fiction Novels from 1904–33 | Radium Age Supermen | Radium Age Robots | Radium Age Apocalypses | Radium Age Telepaths | Radium Age Eco-Catastrophes | Radium Age Cover Art (1) | SF’s Best Year Ever: 1912 | Radium Age Science Fiction Poetry | Enter Highbrowism | Bathybius! Primordial ooze in Radium Age sf | War and Peace Games (H.G. Wells’s training manuals for supermen) | Radium Age: Context series | J.D. Beresford | Algernon Blackwood | Edgar Rice Burroughs | Karel Čapek | Buster Crabbe | August Derleth | Arthur Conan Doyle | Hugo Gernsback | Charlotte Perkins Gilman | Cicely Hamilton | Hermann Hesse | William Hope Hodgson | Aldous Huxley | Inez Haynes Irwin | Alfred Jarry | Jack Kirby (Radium Age sf’s influence on) | Murray Leinster | Gustave Le Rouge | Gaston Leroux | David Lindsay | Jack London | H.P. Lovecraft | A. Merritt | Maureen O’Sullivan | Sax Rohmer | Paul Scheerbart | Upton Sinclair | Clark Ashton Smith | E.E. “Doc” Smith | Olaf Stapledon | John Taine | H.G. Wells | Jack Williamson | Stanisław Ignacy Witkiewicz | S. Fowler Wright | Philip Gordon Wylie | Yevgeny Zamyatin