RADIUM AGE: 1929

By:

November 5, 2022

A series of notes towards a comprehensive account of the science fiction genre’s Radium Age (1900–1935). These notes are very rough-and-ready, and not properly attributed in many cases. More information on Josh’s ongoing efforts here and here.

RADIUM AGE TIMELINE: [1900 | 1901 | 1902 | 1903] | 1904 | 1905 | 1906 | 1907 | 1908 | 1909 | 1910 | 1911 | 1912 | 1913 | 1914 | 1915 | 1916 | 1917 | 1918 | 1919 | 1920 | 1921 | 1922 | 1923 | 1924 | 1925 | 1926 | 1927 | 1928 | 1929 | 1930 | 1931 | 1932 | 1933 | [1934 | 1935]. (The brackets, here, indicate “interregnum” years — i.e., periods of overlap between sf’s Radium Age and its Scientific Romance and so-called Golden Age eras.)

According to my eccentric periodization scheme, the years 1928–1929 are the apex of the cultural decade known as the Teens (1924–1933).

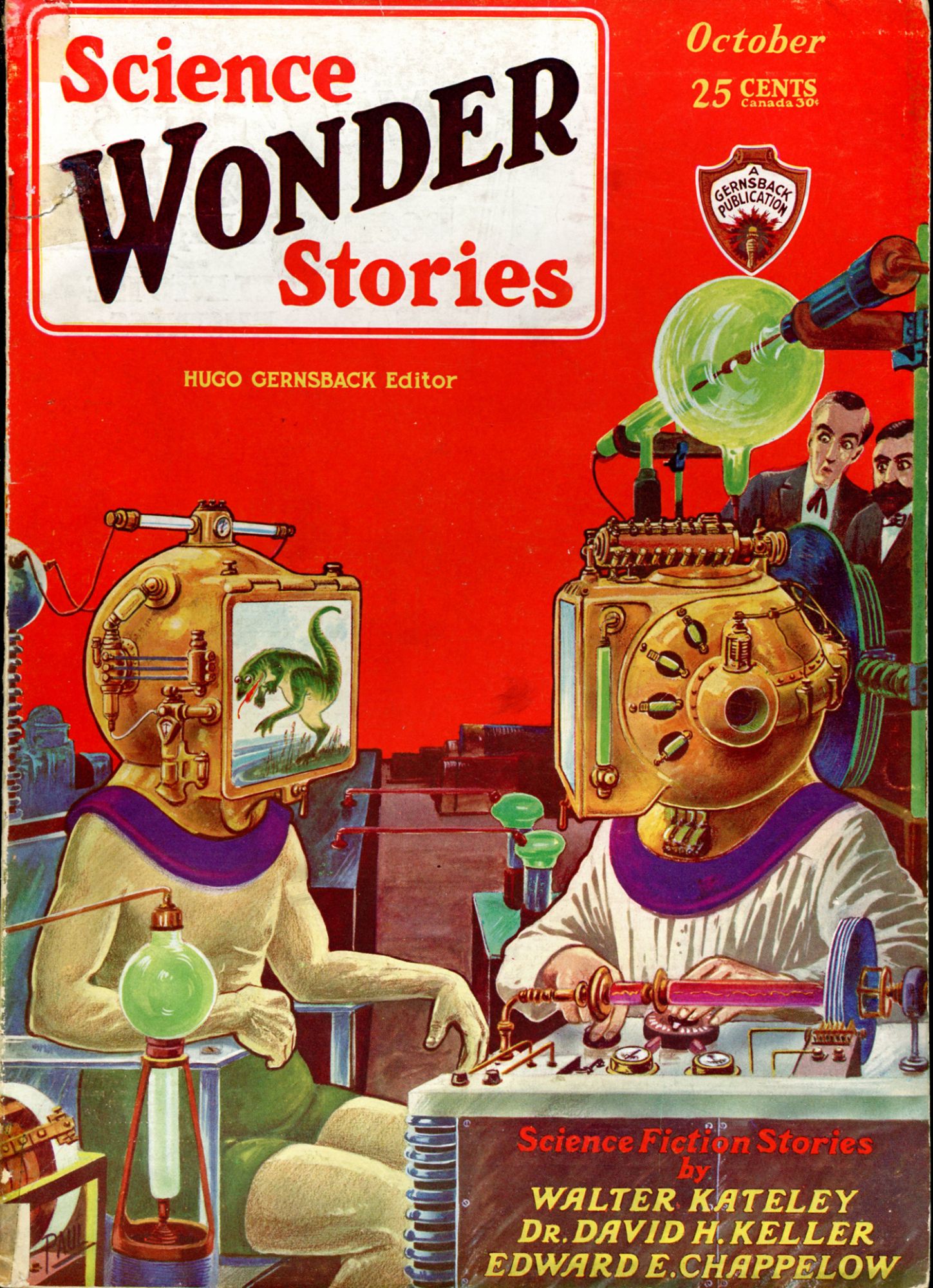

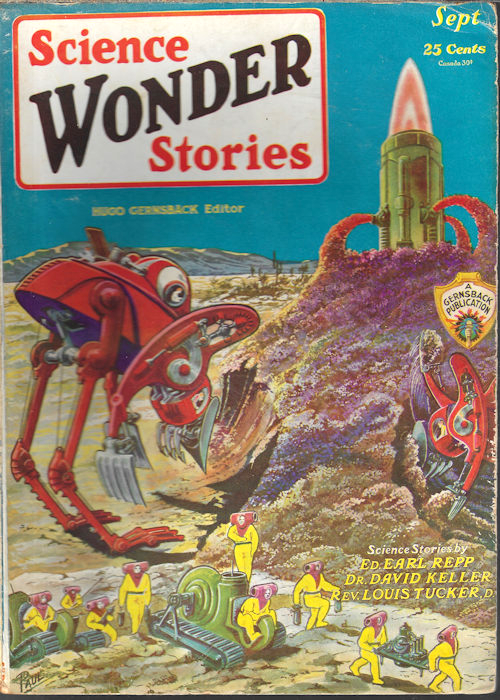

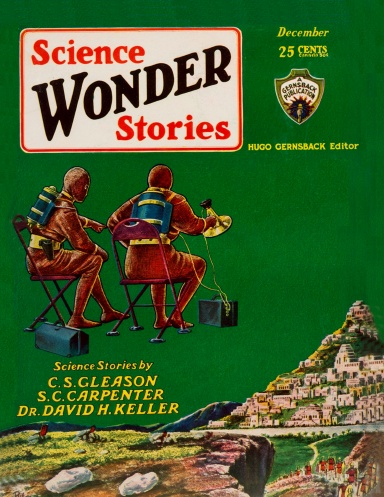

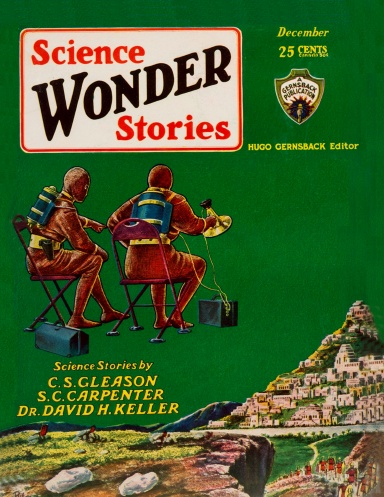

In June 1929, Hugo Gernsback released his second sf-centric periodical, Science Wonder Stories, after having sold Amazing Stories and Amazing Stories Quarterly earlier that year on account of bankruptcy. He also established Air Wonder Stories established in 1929, only to merge it in 1930 with Science Wonder Stories to form Wonder Stories. Both Air Wonder and Science Wonder were edited by David Lasser, who had no prior experience as an editor and who knew little about sf, but whose degree from MIT had convinced Gernsback to take him on.

Because of worries over the trademarked use of his phrase “scientifiction” at Amazing, Gernsback for Science Wonder Stories coined the phrase “science fiction.”

1929 and 1930 saw the first appearance of Neil R. Jones, Lloyd A. Esbach, P. Schuyler Miller, Charles R. Tanner, J. Harvey Haggard, Leslie F. Stone, Ed Earl Repp, Drury D. Sharp, Raymond Z. Gallun, Raymond A. Palmer, Nathan A. Schachner, and John W. Campbell Jr. in Gernsback’s Science Wonder Stories and Air Wonder Stories. Some of these folks share responsibility with Gernsback for reducing the quality of Radium Age sf; others would play key roles in the genre’s so-called Golden Age.

Wonder Stories (“Science” was dropped from the title a year later) featured both new authors and perennial favorites such as Verne and Wells; artist Frank R. Paul continued to provide cover illustrations; and there were numerous features, such as “Science Questions and Answers” and “Science News of the Month,” influenced by Gernsback’s conviction that sf had a place in “making the world a better place,” through an understanding, and extrapolation, of current scientific knowledge.

Despite competition from other sf magazines, most notably Astounding Stories (beginning in 1931), Wonder Stories enjoyed relative success throughout the early 1930s. Circulation dived well below 50,000 by 1936, however, and Gernsback sought to save his periodical by “eliminating the middle man,” as it were, and going straight to his readers, offering a subscription-only title. This strategy ultimately failed, resulting in the selling of Wonder Stories.

Following the sale, the title of the magazine was changed to Thrilling Wonder Stories. Edited by Mort Weisinger (later to helm the Superman titles at DC Comics), the new Wonder emphasized action and adventure, in a more “pulpish” manner than Gernsback’s brainchild. Thrilling Wonder Stories (through several succeeding editors) survived the 1930s and 1940s. It ceased publication in the winter of 1955.

Wonder Stories is now remembered for two significant accomplishments: the discovery of new talent and the fostering (some may even say creation) of science fiction fandom. In addition to presenting early sf’s proven talents, such as Raymond Z. Gallum and John Scott Campbell, Wonder provided a pathway to professional publication for numerous newcomers, such as Raymond A. Palmer (1930), Clifford A. Simak (1931) and Ray Bradbury (1943, first “solo” story).

As with Amazing Stories, Gernsback encouraged communication between his readers in the form of letter columns, competitions, writing contests, clubs, and even the spreading of sf awareness. Through Wonder Stories, Gernsback created one of the first sf communities, the Science Fiction League, which historian Mike Ashley believes “did more for science fiction fandom than anything before or since.”

With these two titles established, Gernsback added Science Wonder Quarterly in October 1929, also edited by Lasser. At the same time Gernsback sent a letter to some of the writers he had already bought stories from, asking for “detective or criminal mystery stories with a good scientific background”, and in January 1930 he launched Scientific Detective Monthly, edited by his deputy, Hector Grey, as a new cross-genre title, giving him four magazines in all.

Copyrighted works from 1929 will enter US public domain on January 1, 2025. They will become free for all to copy, share, and build upon.

Proto-sf coinages dating to 1929, according to the Historical Dictionary of Science Fiction: FEELIE (Indianapolis Times article predicting the future of cinema — three years before Brave New World) | FORCE BEAM (= tractor beam) | GRAVITON (a subatomic particle thought of as propagating the action of gravitational force) | MIND-CONTROLLING | PSEUDOPOD (D. H. Keller’s “Human Termites” in Science Wonder Stories) | RAISE (to cause (a spaceship) to lift off a planet; (of a spaceship) to lift off a planet) | RAY PISTOL (‘H. Vincent’ story in Amazing Stories) | SCIENCE-FICTIONIST (letter in Science Wonder Stories) | SCIENTIFICTIONAL (letter in Amazing Stories Quarterly) | SCIENTIFICTIONIST (editor’s note in Amazing Stories) | SF (Science Wonder Stories, in a list of proposed titles for a science-fiction magazine) | SOL (the star that Earth orbits; the Sun — L.F. Stone story in Amazing Stories) | SPACECRAFT (New York Times) | SPACE SUIT (Science Wonder Stories feature) | STAR SYSTEM (E. Hamilton story in Weird Tales; note that Eddington used the term in 1928) | SUPERSCIENCE (Oakland Tribune story about “Buck Rogers” strip; adopted in 1930 by the magazine Astounding Stories of Super-Science).

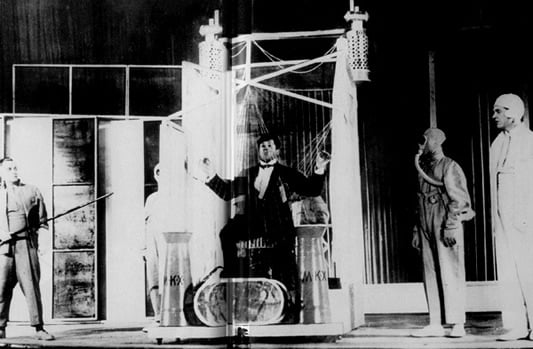

- Vladimir Mayakovsky’s The Bedbug (1929). Delivered — via inadvertent suspended animation — to a future (1979) Soviet society, the worker Prissiypkin discovers that there’s no place for him in a socialist utopia… except, perhaps, as a zoo exhibit. Mayakovsky’s satirical play is directed against the routinization and mechanization of life in an engineered social order; extreme emotions, not to mention love itself, have been superseded. When Prissiypkin plays his guitar and croons, he starts an epidemic of dancing and romance; when he smokes cigarettes and drinks beer, the fumes send hundreds of Russians — who now live sterile, abstemious lives — to the hospital. The play’s humor derives from the earthy, all-too-human responses of Prissiypkin to the new Russia; before his suspended animation, however, Prissiypkin himself — a philistine with boorish manners and poor taste — was the butt of the joke. Fun fact: The play’s 1929 production was directed by Vsevolod Meyerhold, the scenery developed and built by Aleksandr Rodchenko, and the music composed by the young Dmitri Shostakovich.

- Leslie Charteris’s The Last Hero (1929; as a book, 1930). The Saint is an adventurer — a criminal who preys on criminals — and a romantic. “He… had heard the sound of the trumpet, and had moved ever afterwards in the echoes of the sound of the trumpet, in such a mighty clamour of romance that one of his friends had been moved to call him the last hero, in desperately earnest jest.” Unlike other Saint stories, which are realistic crime adventures, here Simon Templar enters the realm of science fiction and spy fiction. The Saint stumbles upon a secret British military installation, where a deadly weapon — the electroncloud machine — is being tested. He also discovers that Rayt Marius, a sinister evil international arms dealer, will stop at nothing to steal the weapon — which he plans to sell to a Balkan country. Determined to prevent Marius and the British government alike from possessing such a weapon, the Saint sets out to kidnap the device’s inventor. Fun fact: Charteris introduced the character of Simon Templar in his 1928 novel, Meet the Tiger. The Last Hero is the third book in the series. The story, which was likely a key influence on Ian Fleming’s James Bond series, was serialized in 1929.

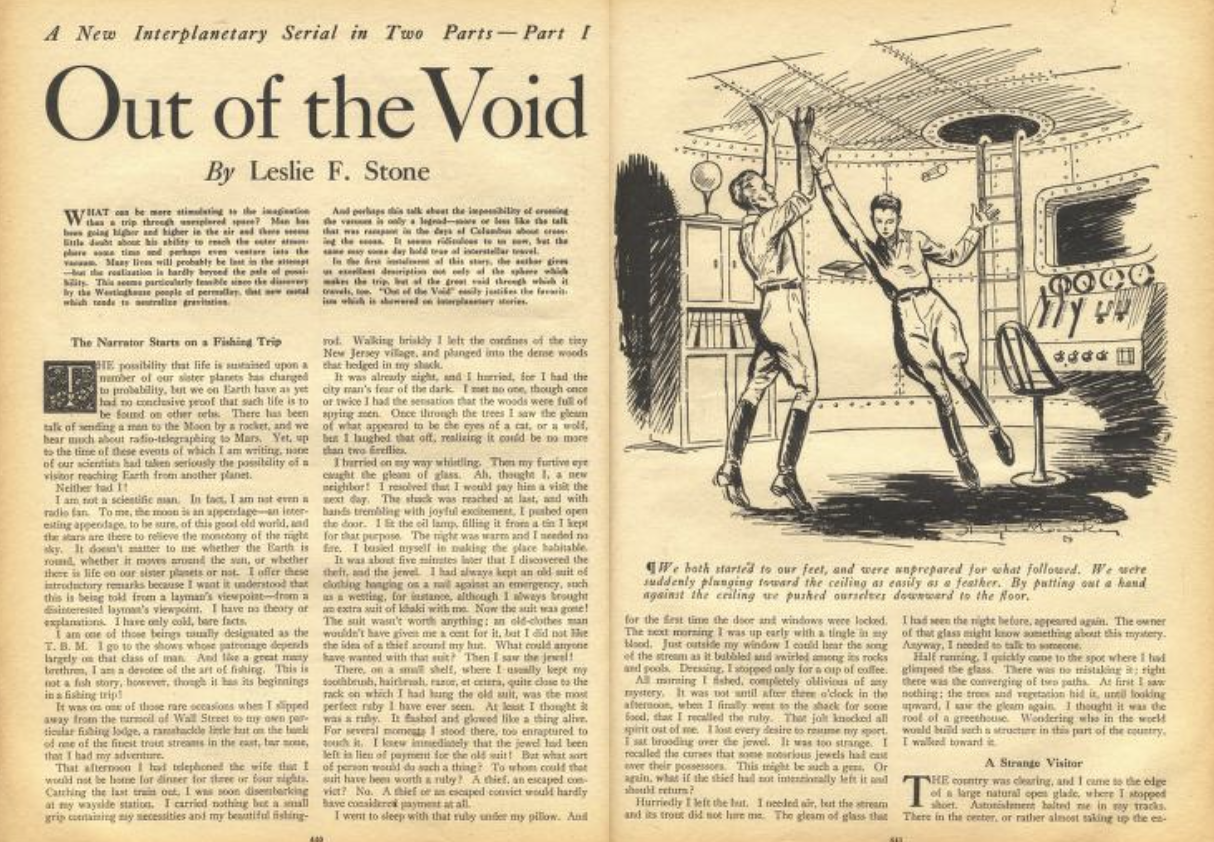

- Leslie F. Stone’s Out of the Void. Complex narrative structure, in a story about the first man in space… who turns out to be a woman. A gender-bending space opera set partially on the ninth planet, Abrui, inhabited by various alien races, some of them telepaths, and featuring adventures in the style of the Planetary Romance. The Amazing 1929 collection says it’s the novel to beat of that year. Followed by “Across the Void” (April-June 1931 Amazing), a Fantastic Voyage tale. Collected in Lisa Yaszek’s Sisters of Tomorrow: The First Women of Science Fiction.

- “The Man Who Hated Flies” by J.D. Beresford. bit of tinkering to rid the world of the lowly housefly has tragic unintended consequences.

- Francis Flagg’s “The Chemical Brain” (Weird Tales, January 1929) Two inventors create the first mechanical man. Rowan is a theosophist while Parsons is an atheist. The two men argue in a friendly way about whether there is life after death. Parsons is secretly having an affair with Rowan’s sister, Genevieve. Lester suspects Rowan knows but holds his tongue. The robot is finally finished when a lumpy mass is placed in the brain pan. At this moment, Rowan has a heart attack and dies. The robot comes to life after a period of time and breaks into the house, attacking and killing Parsons. No doubt influenced by Edmond Hamilton’s earlier robot stories, Flagg delineates the robot idea fully, including robots that make robots, terrible job loss, and even a war with the robots.

- Leslie F. Stone’s When the Sun Went Out. Editor Hugo Gernsback; Frontis by Frank R. Paul. First edition in book form, published as “Science Fiction Series” No. 4.

- Ivo Šorli’s V deželi Čirimurcev (In the Land of Chirimurs). Introduced the motif of parallel worlds into Yugoslav science fiction.

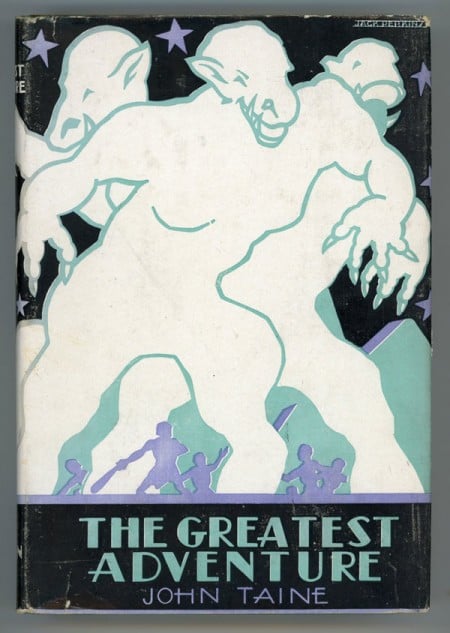

- John Taine’s The Greatest Adventure (1929). An expedition sent to Antarctica discovers remnants of an ancient culture — an elder race, with advanced technology — that was lost when it was overwhelmed by the Ice Age. (Note that this novel predates Lovecraft’s At the Mountains of Madness by a couple of years.) These ancients had discovered the secret of causing plants and animals to grow larger — but they were too incautious in their experiments. The mutations got out of control… so the civilization entombed itself in ice. Finally, the party must flee through caverns inhabited by the mutated life forms. Worse, when frozen spores are thawed out, the entire planet is threatened by parasitic, malign plant life. A tale of horror and madness — but it’s not without humor, in the form of ship’s first mate Ole Hansen. Fun fact: Eric Temple Bell was a Scottish-born American mathematician; Bell polynomials and the Bell numbers of combinatorics are named after him. He wrote sci-fi as John Taine. The MIT Press’s Radium Age series plans to reissue this book.

- Helen Beauclerk’s The Love of the Foolish Angel. See this list of Pre-1950 Utopias and Science Fiction by Women.

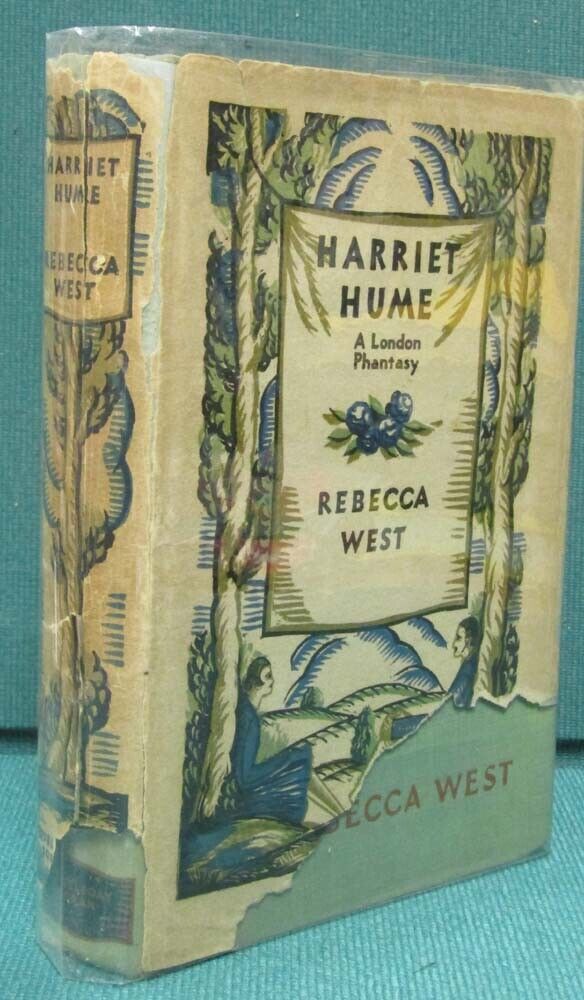

- Rebecca West’s Harriet Hume: A London Fantasy. A modernist story about a piano-playing prodigy and her obsessive lover, a corrupt politician. The protagonist’s power of telepathy renders her intolerable to her self-serving aspirational lover; the tale climaxes as a posthumous fantasy. Fun facts: Pseudonym of UK journalist and author Cicily Isabel Fairfield Andrews (1892-1983), H G Wells’s partner 1913-1923. Her major works include Black Lamb and Grey Falcon (1941), on the history and culture of Yugoslavia; A Train of Powder (1955), her coverage of the Nuremberg trials, published originally in The New Yorker; The Meaning of Treason (first published as a magazine article in 1945 and then expanded to the book in 1947), a study of the trial of the British fascist William Joyce and others; The Return of the Soldier (1918), a modernist World War I novel; and the “Aubrey trilogy” of autobiographical novels. See this list of Pre-1950 Utopias and Science Fiction by Women.

- Lillian Elizabeth Roy’s The Prince of Atlantis. US author perhaps best known for the Polly Brewster series of adventure stories for girls. Of some sf interest, The Prince of Atlantis describes the flight of Atlanteans from volcano-shattered Atlantis; most end up in the headwaters of the Nile, though some have stayed to embed the secret of Atlantis in the Sphinx, which they have constructed for that purpose. See this list of Pre-1950 Utopias and Science Fiction by Women.

- Mavis Elizabeth Hocking Nisot (as William Penmare)’s The Man Who Could Stop War. A Near Future tale in which the invention of an immobilizing gas helps thwart a Russian invasion. See this list of Pre-1950 Utopias and Science Fiction by Women.

- Bertha Louisa Bowhay’s Elenchus Brown: The Story of an Experimental Utopia compiled by a Student of Battersea Polytechnic.. See this list of Pre-1950 Utopias and Science Fiction by Women.

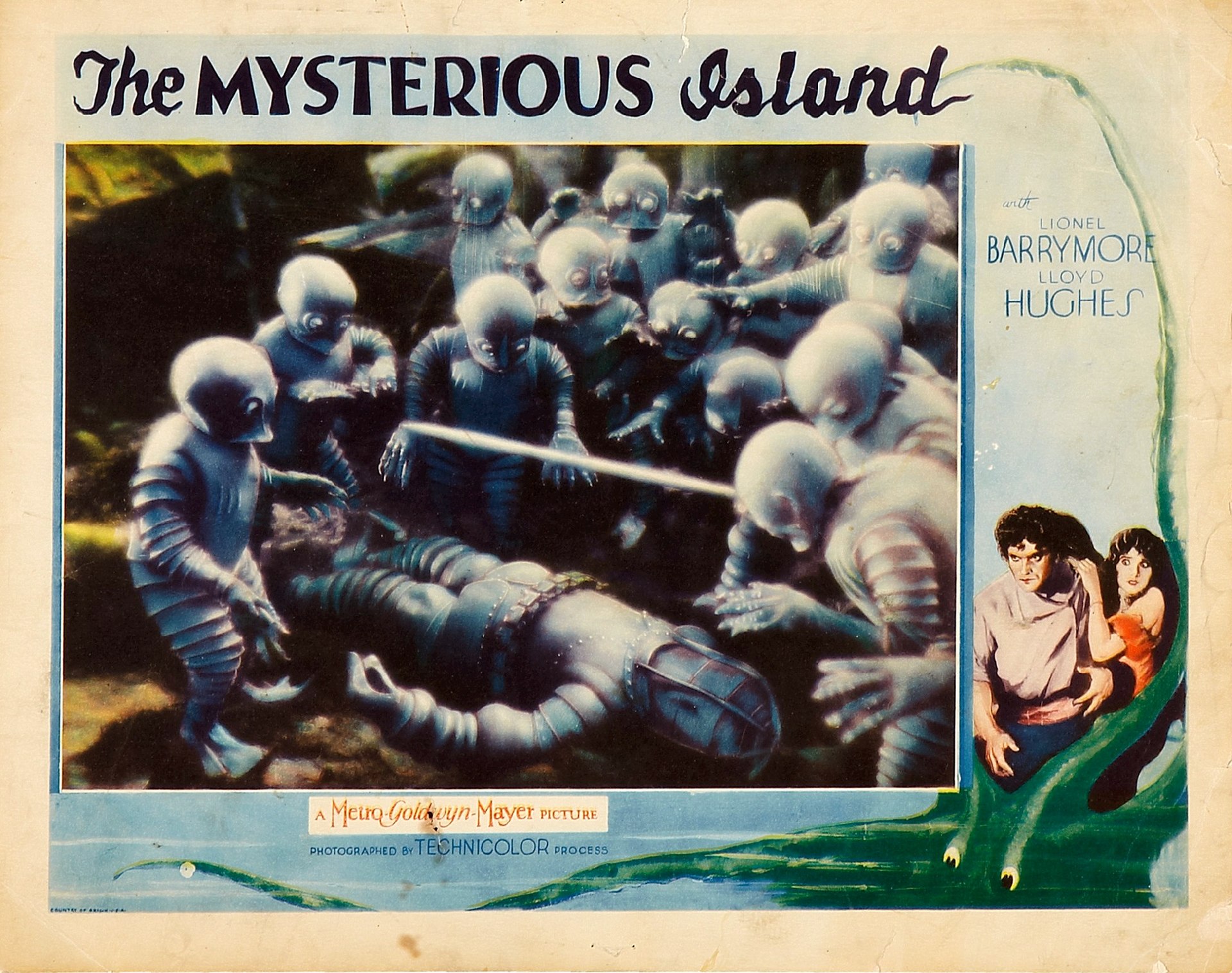

- The Mysterious Island is a 1929 American science fiction film directed by Lucien Hubbard, based on Jules Verne’s 1874 novel L’Île mystérieuse. It was photographed largely in two-color Technicolor and released by Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer as a part-talkie feature, with some scenes with audible dialog and some that had only synchronized music and sound effects. On a volcanic island near the kingdom of Hetvia rules Count Dakkar, a benevolent leader and scientist who has eliminated class distinction among the island’s inhabitants. Dakkar, his daughter Sonia and her fiance, chief engineer Nicolai Roget, have designed a submarine boat which Roget pilots on its initial test voyage shortly before the island is overrun by Baron Falon, once Daggar’s friend, and now the new despotic ruler of Hetvia. The Baron has Dakkar and his daughter tortured so that Dakkar will reveal all his discoveries.

- Sarah Comstock’s The Moon Is Made of Green Cheese. Of sf interest for its portrait of an astronomer (see Astronomy) responsible for some controversial findings and who engages in discussions with a mentor. His friends describe this mentor as an imaginary being; the astronomer’s own description, if taken literally, would define his mentor as an alien. See this list of Pre-1950 Utopias and Science Fiction by Women.

- Francis Flagg’s “The Dancer in the Crystal” (Weird Tales, December 1929) has something like an EMP wipe out all electricity throughout the world, plunging everyone into darkness, dropping planes from the sky. Years after the event, a writer interviews the only man, Peter Ross, who can explain the pillar of fire seen burning up into the sky from the prairies of Alberta. Ross tells how he and an under-professor of Physics at McGill University, John Cabot, stole three spheres that came to Earth in a meteorite. Each of the smooth glass eggs has a swirling black dot dancing inside it. The two men go to the wilds of Alberta break open one of the spheres. The huge pillar of electrical-sucking energy explodes from the shell. The black dot forms into an evil presence that devours Cabot and wants Ross. Cabot’s voice tells Ross to smash the second sphere in his backpack. When he does this, the two beings join and fire off into space. The second half of the story is reminiscent of H. P. Lovecraft’s “The Colour Out of Space.”

- Nathalia Crane’s An Alien from Heaven. She enjoyed a long career as an academic and political activist. Samuel R. Delany mentions her in Atlantis: Model 1924 (1995). Of sf interest are two novels: The Sunken Garden (1926), a Lost Race tale set in Africa, where the young female protagonist discovers a perfect lover and they, decorously, mate; and An Alien from Heaven, in which a baby born with wings inspires scientists to debate whether or not the child is a throwback or a visitation from the future. See this list of Pre-1950 Utopias and Science Fiction by Women.

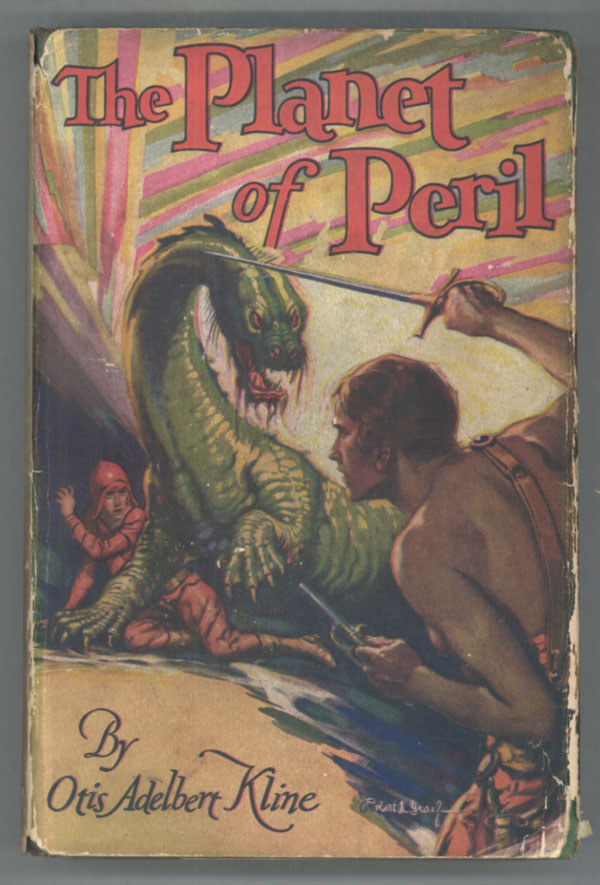

- Otis Adelbert Kline’s The Planet of Peril. The author’s first book. First published as a six-part serial in ARGOSY, 20 July – 24 August 1929. The first of the three Grandon of Venus novels. Swordplay and fantastic adventure in imitation of Edgar Rice Burroughs. See 1929.

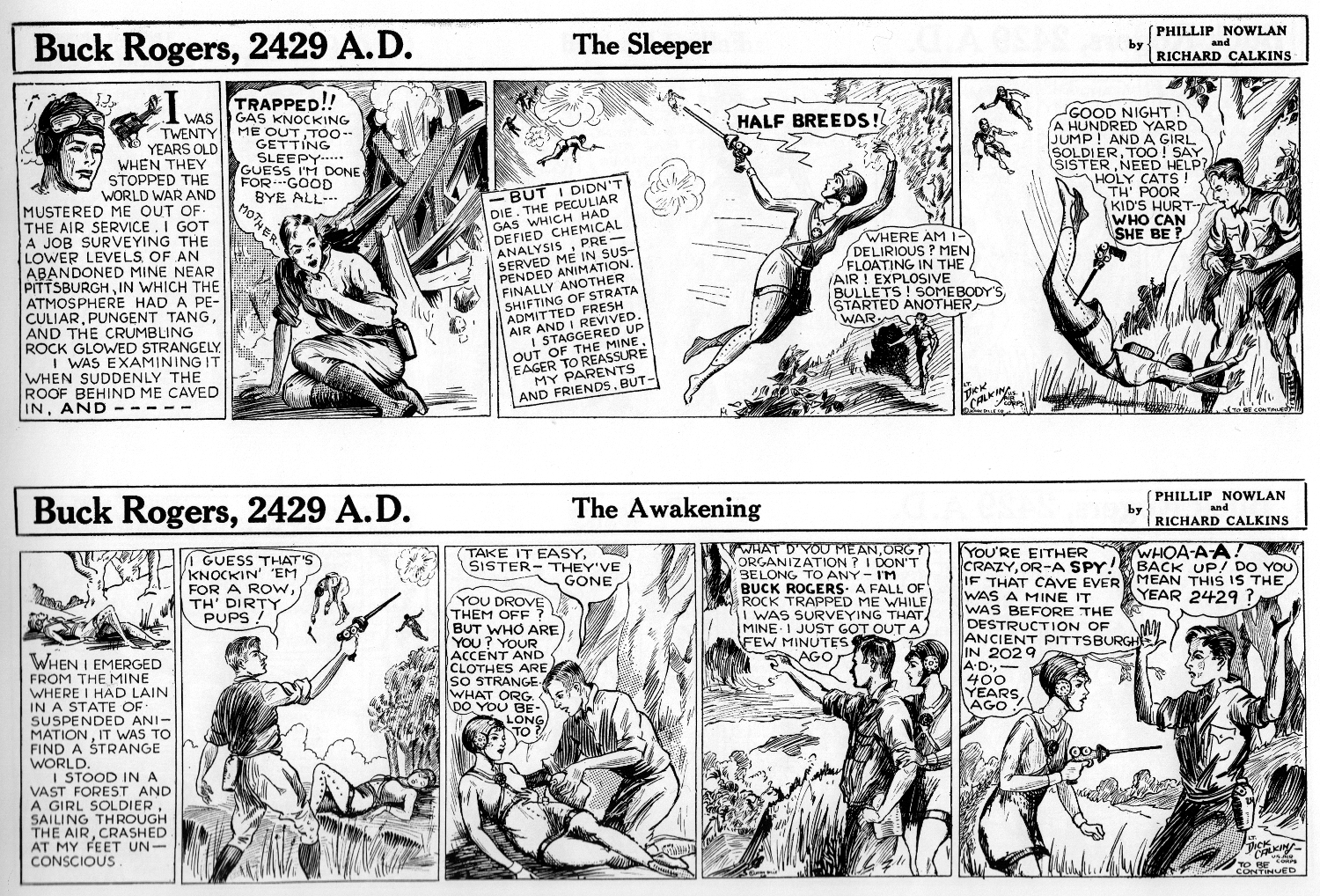

- Buck Rogers — the original sf comic strip. Anthony Rogers first appeared in the sf story “Armageddon 2419 A.D.” by Philip Francis Nowlan in the August 1928 issue of Amazing Stories. (See 1928.) Syndicate head John F. Dille signed Nowlan to write a comic strip based on the concept. Dille’s Chicago-based syndicate hired cartoonist Dick Calkins to illustrate the new feature. Inside of six months the idea went from published story to syndicated comic strip. Along the way Anthony Rogers became Buck Rogers. It subsequently appeared in Sunday newspapers, international newspapers, books and multiple media with adaptations including radio in 1932, a serial film, a television series, and other formats. Buck Rogers has been credited with bringing into popular media the concept of space exploration; it was on January 22, 1930, that BR first ventured into space aboard a rocket ship in his fifth newspaper comic story “Tiger Men from Mars.” The first Buck Rogers toys appeared in 1933, four years after the newspaper strip debuted and a year after the radio show first aired. Some mark this as the beginning of modern character based licensed merchandising, in that not only was the character’s name and image branded on many unrelated products, but also on many items of merchandise unique to or directly inspired by that character. Of the many toys associated with Buck Rogers, none is more closely identified with the franchise than the eponymous toy rayguns.

- A.G. Stangland’s “The Ancient Brain.” Collected in From Off This World: Gems of Science Fiction Chosen From “Hall of Fame Classics” (1939).

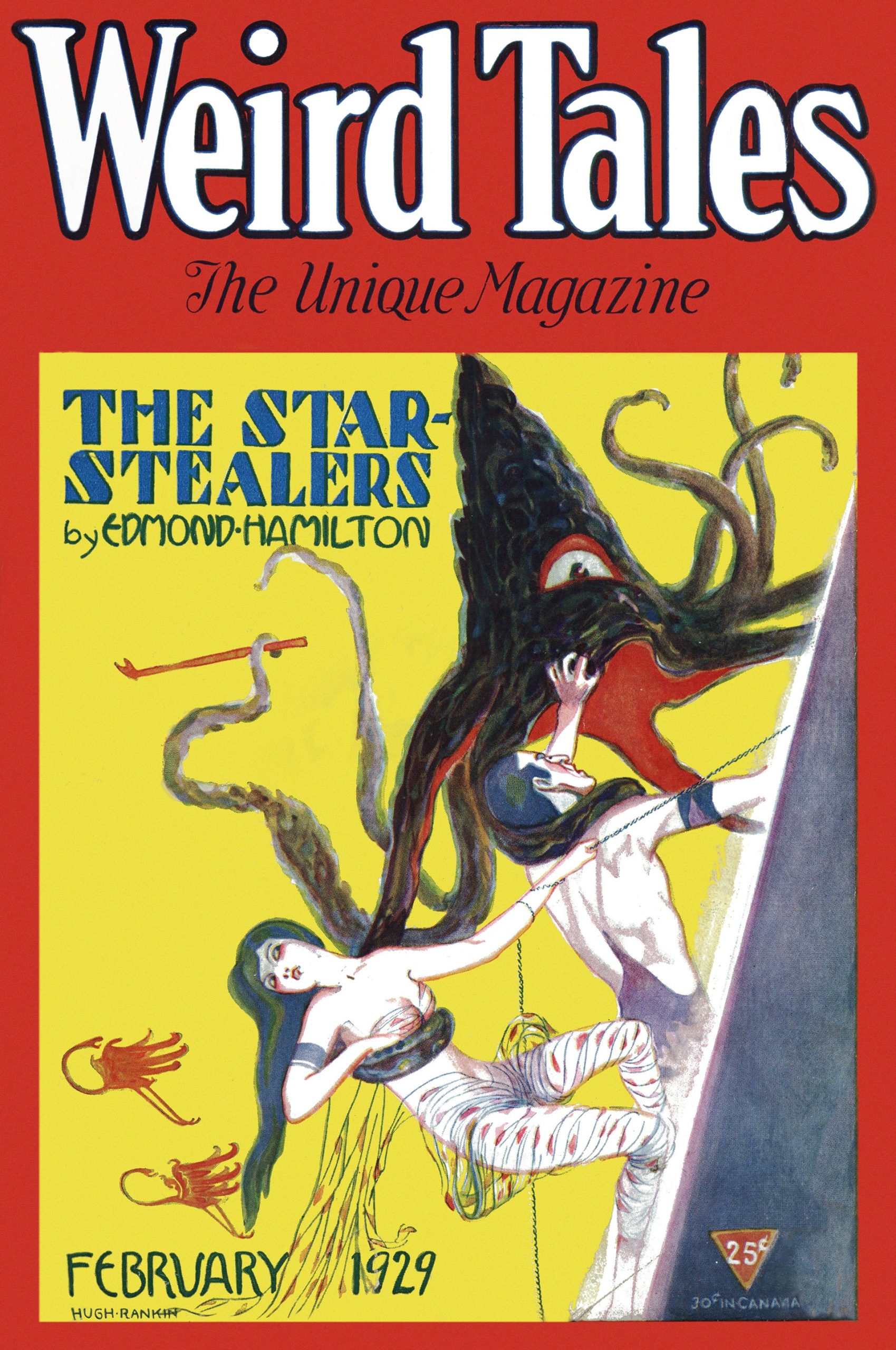

- Edmond Hamilton’s “The Star-Stealers.” In Weird Tales. Beginning of a space opera series — based on the seminal “Crashing Suns” (Weird Tales, 1928) — about the Interstellar Patrol. Also: “Within the Nebula” (1929), “Outside the Universe” (1929), “The Comet-Drivers” (1930), “The Sun People” (1930), and “The Cosmic Cloud” (1930). With the exception of “The Sun People”, the stories were assembled as Crashing Suns in 1965.

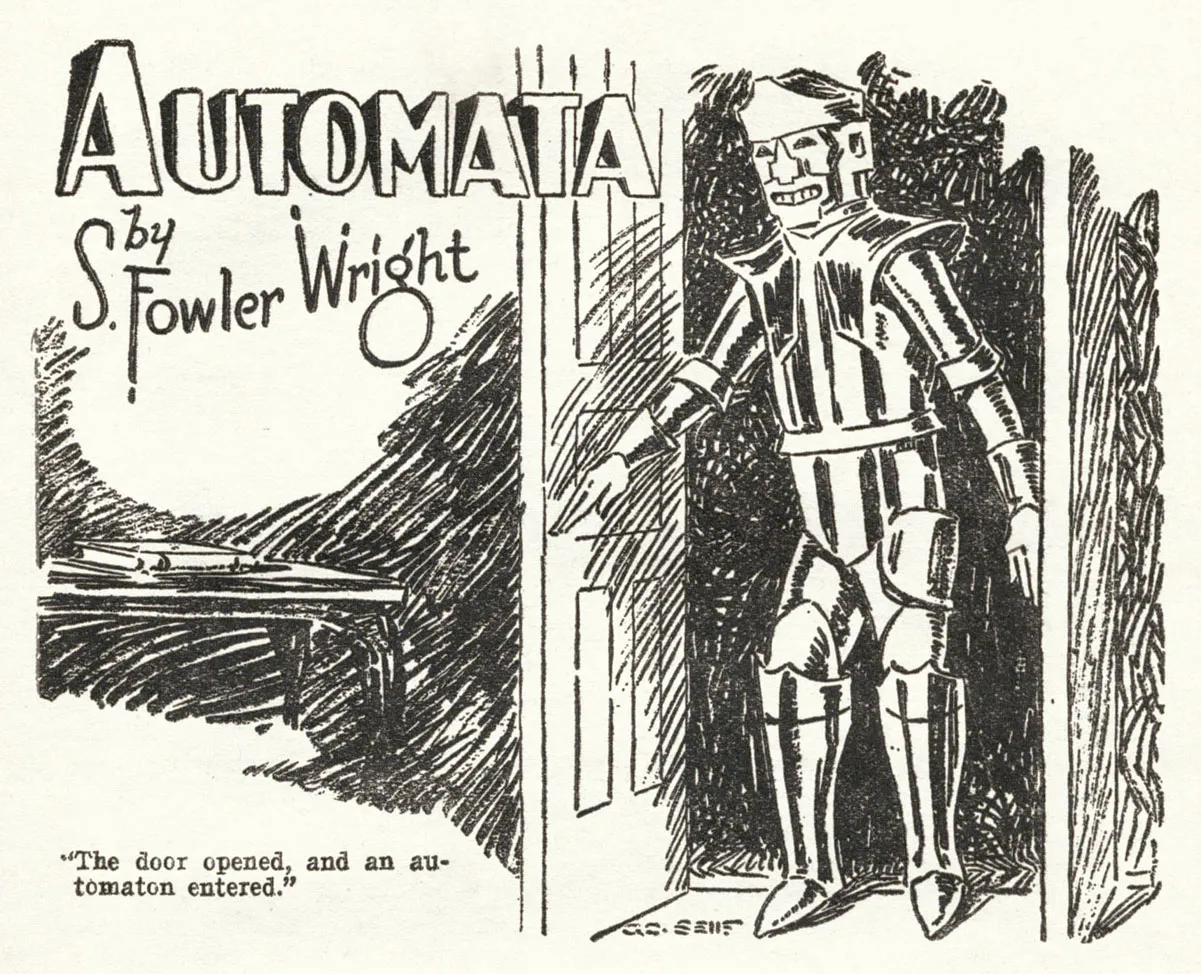

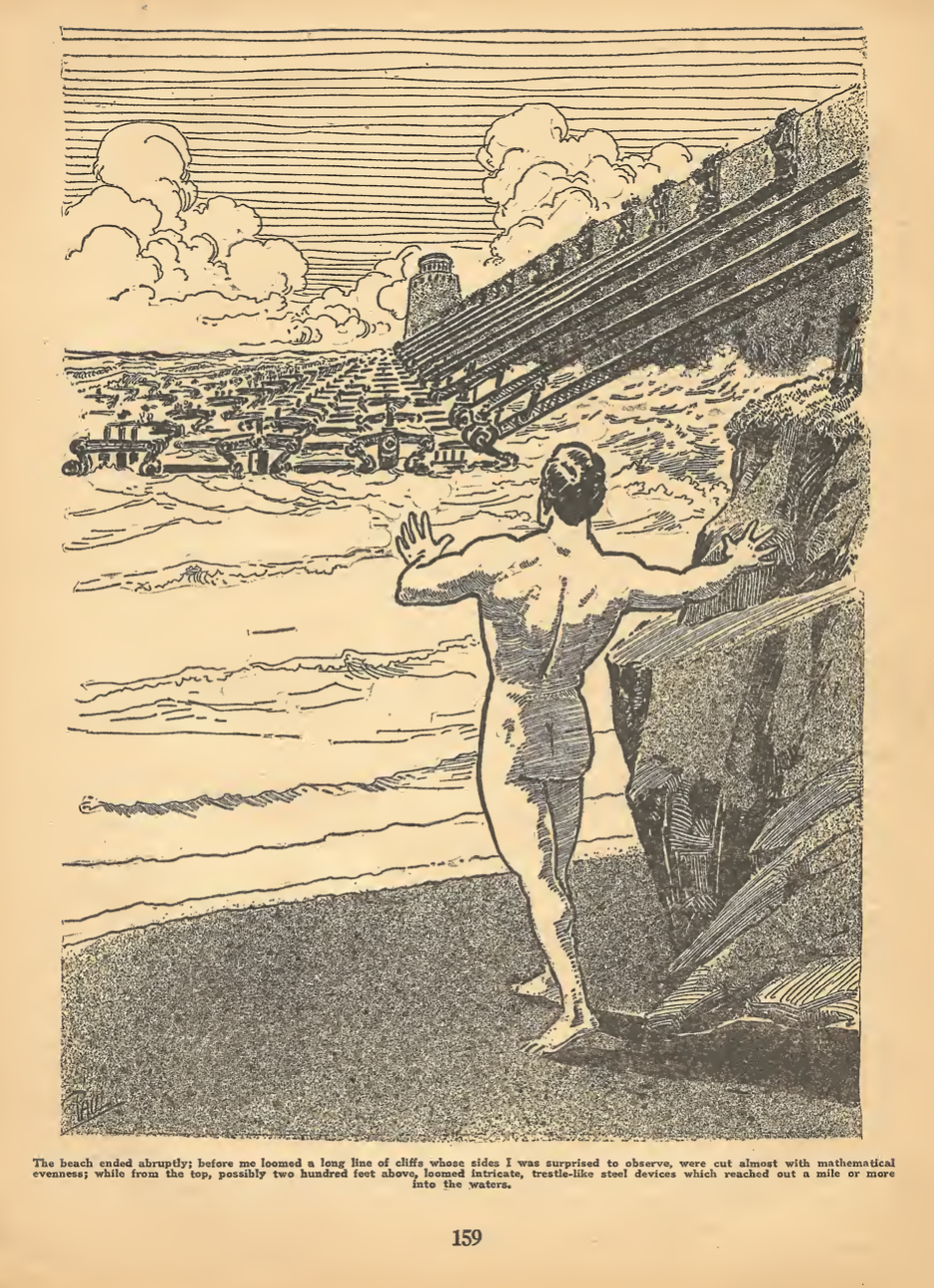

- S. Fowler Wright’s Automata (three parts; Weird Tales. The first episode of this three-part series is set in the present or near future. Addressing the British Association for the Advancement of Science, the distinguished scientist Dr. Tilwin announces that humankind’s prerogatives will soon be taken over by machines, which are already superior to us in certain ways. Artificial intelligences are omnipresent in the second episode, set at some point after the 20th century. By this time, human procreation has almost stopped (Wright, a would-be Wellsian social prophet, was a fierce critic of birth control) and children are increasingly rare. In the final episode, one of the last humans on Earth is drawing a picture — one of the few tasks that machines can’t perform, because it requires imagination. (Apparently Wright couldn’t foresee Dall-E and Midjourney.) Alas, because he doesn’t properly finish his assignment, he is condemned to be executed. Fun facts: Robots wouldn’t come hardwired with systems of ethics until Isaac Asimov and John W. Campbell would make it so in the ’40s.

- E.H. Visiak (working name of UK poet, critic and author Edward Harold Physick)’s Medusa: A Story of Mystery, and Ecstasy, & Strange Horror. An almost surreal fantastic voyage into unknown seas. Gives the eponymous South Pacific sea monster, which dwells in a vast hole under the sea, an sf-like rationale.

- Edmond Hamilton’s “The Other Side of the Moon” (Fall 1929 Amazing Stories Quarterly). This story is used by the SFE as an example of how “spectacular genocide became commonplace” in the pulps.

- A. Hyatt Verrill’s “Vampires of the Desert” (Amazing). Bleiler calls it Verrill’s best story — about prehistoric plants. I’m not that impressed by it.

- A. Hyatt Verrill’s “Death from the Skies” (Amazing). Martians use meteorites to bombard Earth.

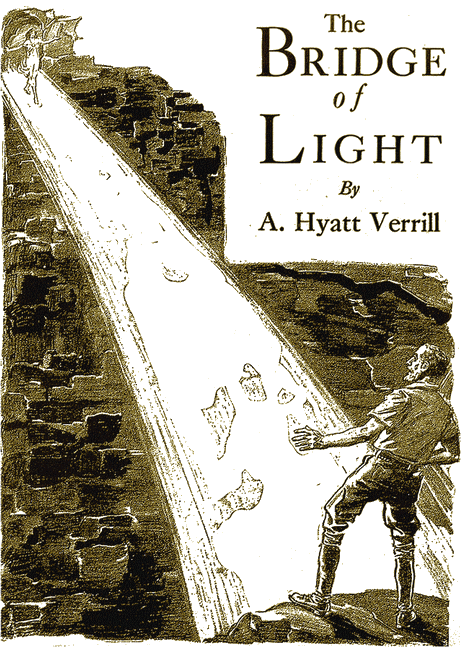

- A. Hyatt Verrill’s The Bridge of Light (Amazing). Novel about Mayans, science of a lost civilization. P. Schuyler Miller praised it.

- Adalzira Bittencourt’s Sua Excelência, a Presidente da República no ano 2500 (“Her Excellency, the President of the Republic in the Year 2500”). Brazilian novel depicting a futuristic Brazil — with a heavy eugenics bent.

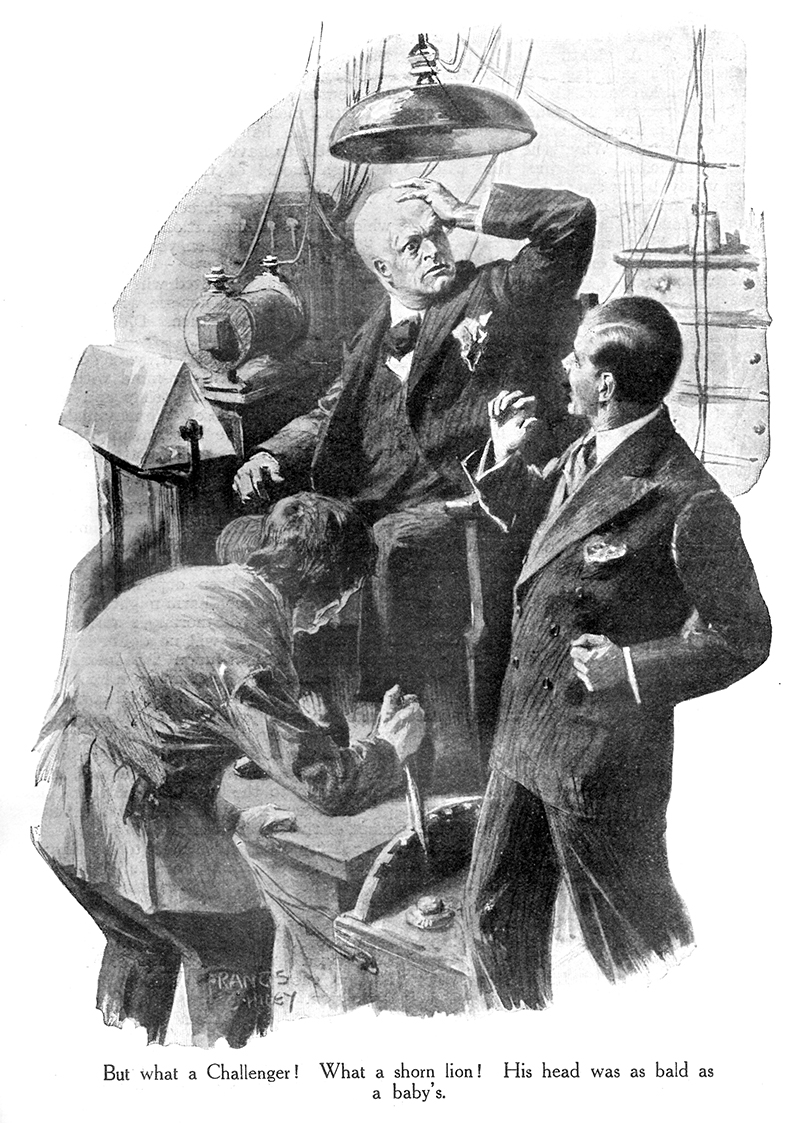

- Arthur Conan Doyle’s “The Disintegration Machine.” (The Strand magazine, January 1929.) The story centers on the discovery of a machine capable of disintegrating objects and reforming them as they were. Challenger, after losing his magnificent head of hair (cf. Lex Luthor’s origin story) saves the world.

- Bob Olsen’s “The Superperfect Bride” (Amazing). One of the most celebrated stories of the era — involves nudity and arousal — but ultimately I don’t think it is actually sf.

- Charles Cloukey’s novelette Paradox. Supposedly outstanding work still acclaimed today — certainly his most accomplished work. Cloukey’s death at the age of 19 robbed the field of a precocious talent. His first sale was made when he was only fifteen, “Sub-Satellite” (March 1928 Amazing). It raised the interesting question of what happens in lunar gravity when bullets are fired on the Moon. Cloukey’s most accomplished stories were a trilogy, clearly inspired by Wells, starting with the Club Story format with time paradoxes at their core, though predominantly involving far future intrigue in Earth’s war with Mars: Paradox (Summer 1929 Amazing Stories Quarterly), “Paradox +” (July 1930 Amazing) and “Anachronism” (December 1930 Amazing).

- Clare Winger Harris’s “The Artificial Man.” Features a character named George Gregory (who is not the same George Gregory from her story “The Fate of the Poseidonia”). Gregory is a relatively optimistic man, even after he loses a leg following an accident on the football field shortly before his scheduled wedding to Rosalind Nelson. However, after he loses an arm in an auto accident, again postponing his wedding, he begins to become bitter and wonders how much of his physical body could be replaced without damaging his mental facility and his sense of soul. As with the other Gregory, his curiosity costs him his fiancé. Harris’s depiction of a cyborg from 1929 is ahead of its time and Gregory’s ideas about body and soul working together add a nice dimension to the character. Republished in 2015 by Mike Ashley in The Feminine Future: Early Science Fiction by Women Writers.

- Clare Winger Harris’s “A Baby on Neptune” with Miles J. Breuer (Amazing). Scientists can’t find life on Neptune because the lifeform there is gaseous and moves too slowly.

- Clare Winger Harris’s “The Diabolical Drug” (Amazing — May issue, after Gersnback left). The driving force is Edgar Hamilton’s desire to marry Ellen Gordon, six year’s his elder, which is the only reason Ellen spurns his advances. Hamilton’s solution is to administer a drug which will retard her aging, and then an antidote when he becomes older than she is. Hamilton’s plans don’t work out as well as he would like and he winds up quickening his own aging, only to find himself in an alternative reality.

- Clare Winger Harris’s “The Evolutionary Monstrosity” (Amazing). Harris depicts biologists using bacteria to speed up the evolutionary process, questioning how well evolution of the body without a changing environment would work and where it would fall apart. Her scientist, Ted Marston, along with his friend Irwin Staley, explore the possibilities, while their friend Frank Caldwell maintains his distance and provides an outside voice of reason to question their methods and support the idea of their research. Although Marston creates a horror, Harris does not write a story in which the moral is that there are things man was not meant to know, instead showing that science has a place and can and should probe the unknown, with precautions in place.

- Daniel Dressler’s “The White Army” (Amazing). Bleiler calls it an “exceptionaly literate” story about a white corpuscle.

- David H. Keller’s The Human Termites. Lurid tale of war and miscegenation. Begins as a relatively calm-minded development of the speculative element in La Vie des termites (1926; trans Alfred Sutro as The Life of the White Ant 1927) by Maurice Maeterlinck, but soon leaves behind the commonplace supposition of a termite Hive Mind, moving into an almost delirious account in which both termites and humans are seen to be governed by totalitarian central intelligences! The novel’s exorbitance caused considerable stir in 1929 fandom, but in retrospect can be understood as comprising – at least in part – a dystopian extrapolation of the horrors of mass combat in WWI. The introduction to the 1979 book edition, by Patrick H. Adkins, is said to be illuminating. A physician and psychiatrist, Keller was deeply involved in the last capacity in WWI and its consequences, his work focusing on shell shock, a fact that may help explain his abiding cultural pessimism,

- David H. Keller’s The Conquerors. In the book-length The Conquerors (December 1929-January 1930 Wonder Stories), a dwarf race, separated Underground from human stock for millennia, conquers part of America. Eventually, the race decides to colonize Venus.

- David H. Keller’s “The Feminine Metamorphosis” (Wonder Stories). An anti-feminist imagines what would happen if women were given the same opportunities as men. Both repels and confuses with its punitive rendering of female-to-male sex change, in which ruthless women inject extracts from the severed genitals of Chinese men, which transforms them into male entrepreneurs (until syphilis kills them off). Mentioned in Moskowitz’s collection When Women Rule. A savage attack on the increasing social power of women; a bizarre and stupid story.

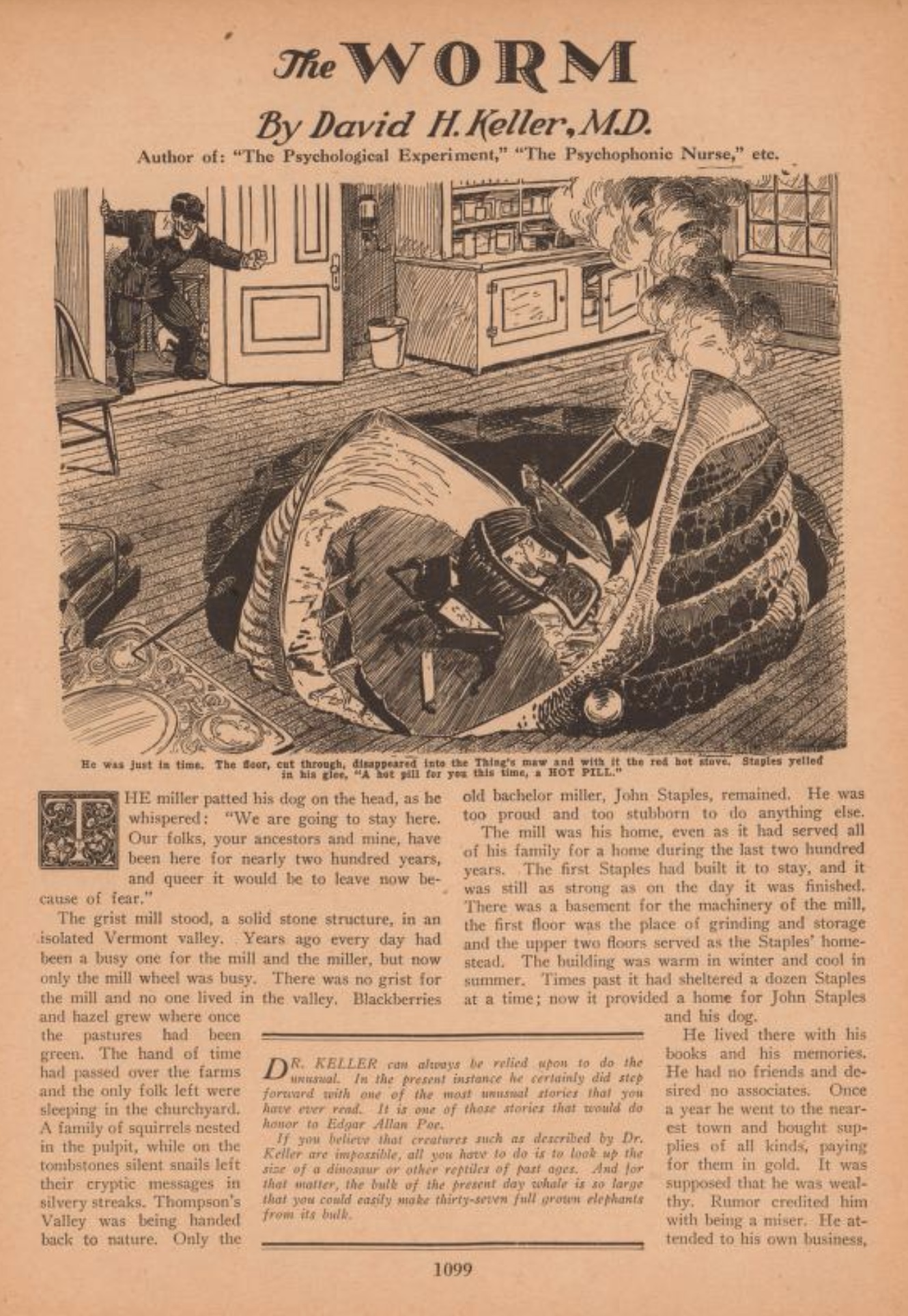

- David H. Keller’s “The Worm” (Amazing). Frequently reprinted — but is it more horror than sf?

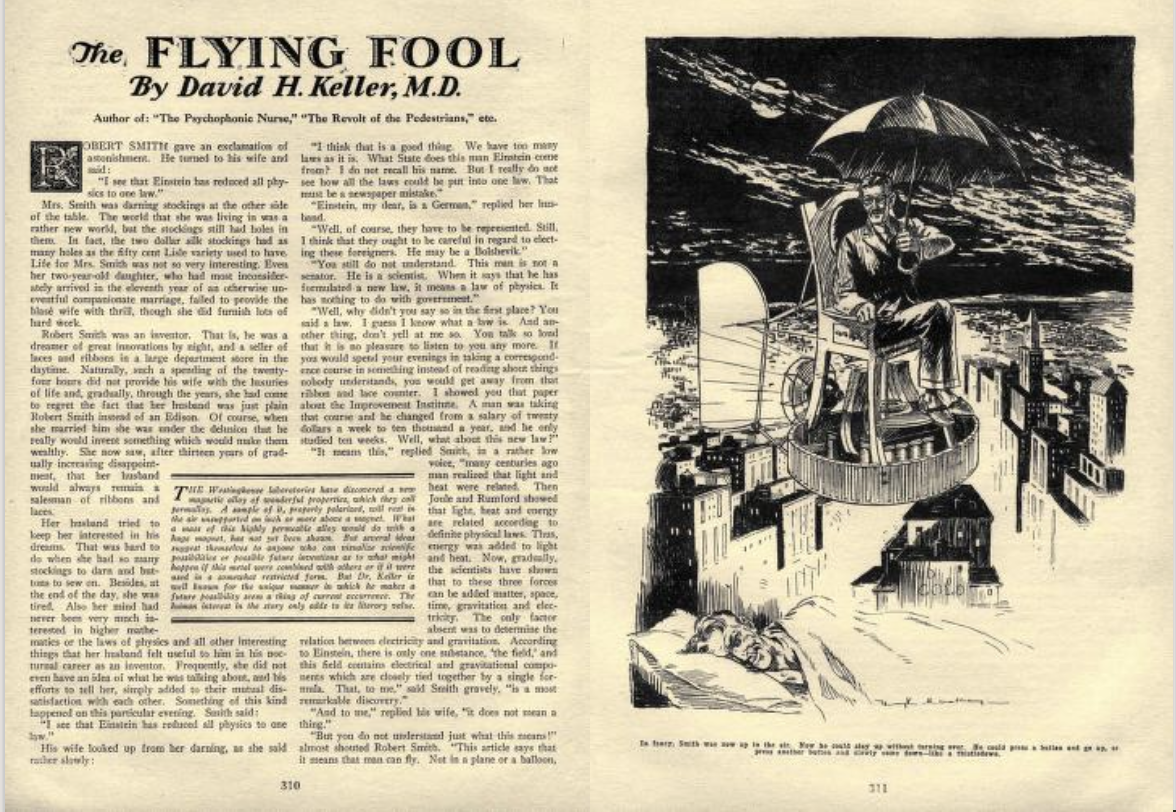

- David H. Keller’s “The Flying Fool” (Amazing). One of the most celebrated stories of the era, according to Moskowitz, who calls it a tale of superb artistry.”

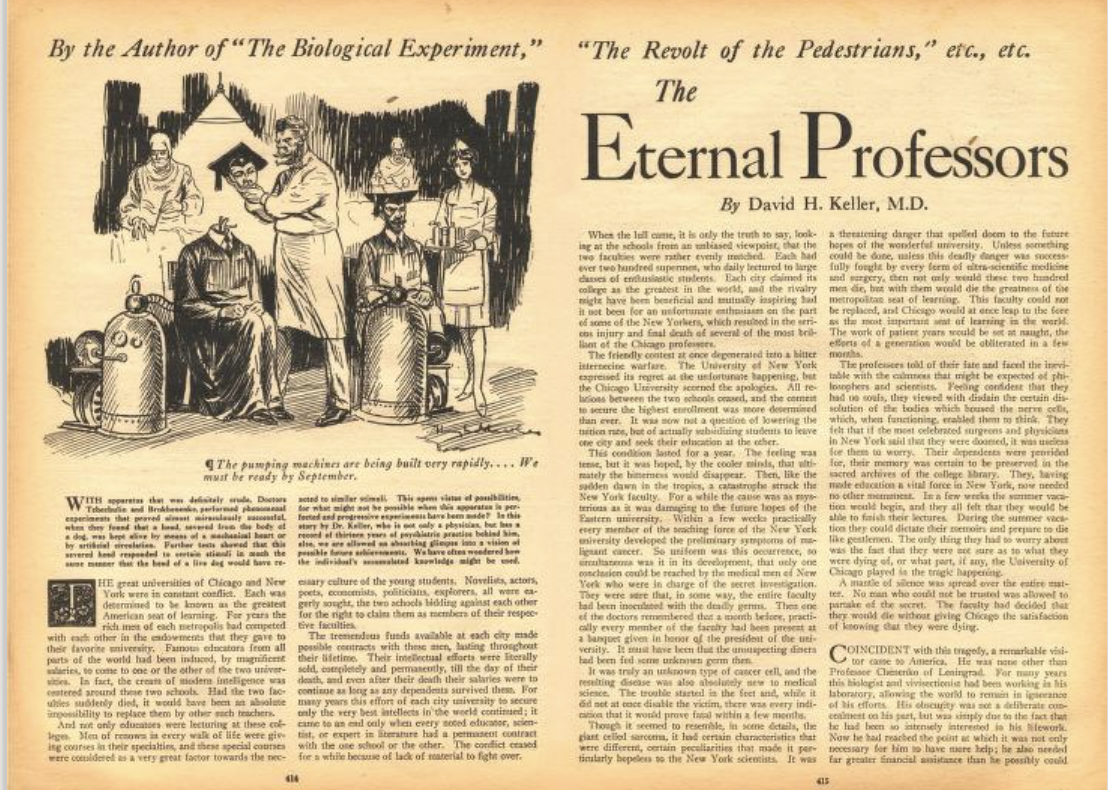

- David H. Keller’s “The Eternal Professors” (Amazing). Black humor.

- Morrison Colladay’s When the Moon Fell. Full-page illustration by Frank R. Paul. Published by Hugo Gernsback as “Science Fiction Series” No. 6.

- David H. Keller’s “White Collars” (Amazing). Supposedly outstanding work still acclaimed today; sharply extrapolated social satire.

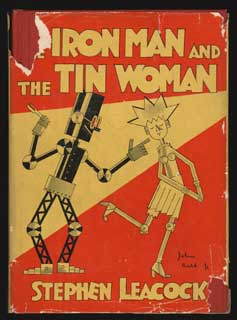

- Stephen Leacock’s The Iron Man & The Tin Woman. A collection of humorous sketches, many utilizing science fiction themes, some set in the future.

- E. Arnot Robertson’s “Three Came Unarmed.” Robertson was one of the few female writers of the era. In a striking attack on modern civilization, the story exposes three enfants sauvages from the Far East to contemporary England; they are in fact examples of homo superior, but England destroys them.

- Ed Earl Repp’s “Beyond Gravity.” Repp’s first sf story — for Air Wonder Stories in August 1929 – appeared simultaneously with the magazine publication of his first novel, The Radium Pool (August-September 1929 Wonder Stories. SFE says: “He wrote a large number of fairly unremarkable pulp-magazine adventures for about a decade from 1929, ceasing to produce sf during World War Two, after his work as a screenwriter began to pick up; between 1934 and 1957 he wrote about fifty scripts, all Westerns.”

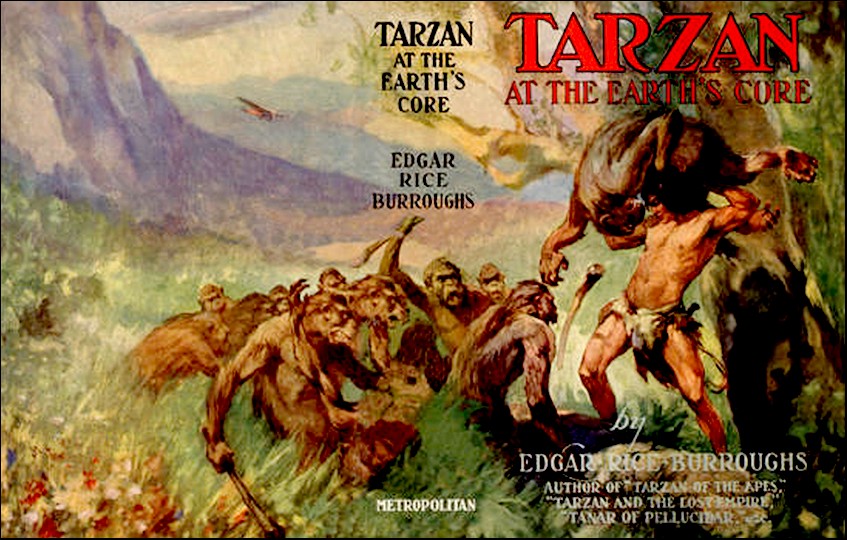

- Edgar Rice Burroughs’s Tarzan at the Earth’s Core. Serialized September 1929 to March 1930. The thirteenth in Burroughs’s series of twenty-four books about Tarzan and the fourth in his series set in the interior world of Pellucidar. In response to a radio plea from Abner Perry, a scientist who, with his friend David Innes, has discovered the interior world of Pellucidar at the Earth’s core, Jason Gridley launches an expedition to rescue Innes from the Korsars, the scourge of the internal seas. He enlists Tarzan, and a fabulous airship is constructed to penetrate Pellucidar via the natural polar opening connecting the outer and inner worlds. The airship is crewed primarily by Germans, with Tarzan’s Waziri warriors under their chief Muviro also along for the expedition.

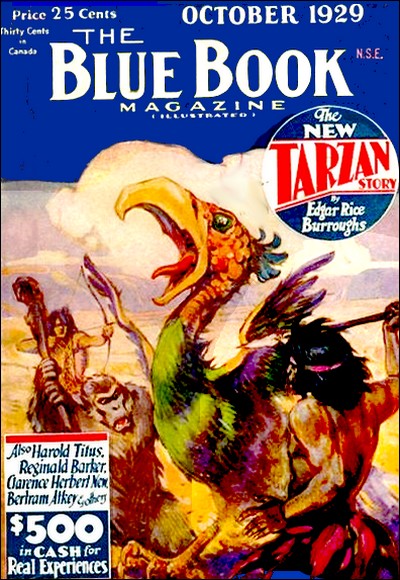

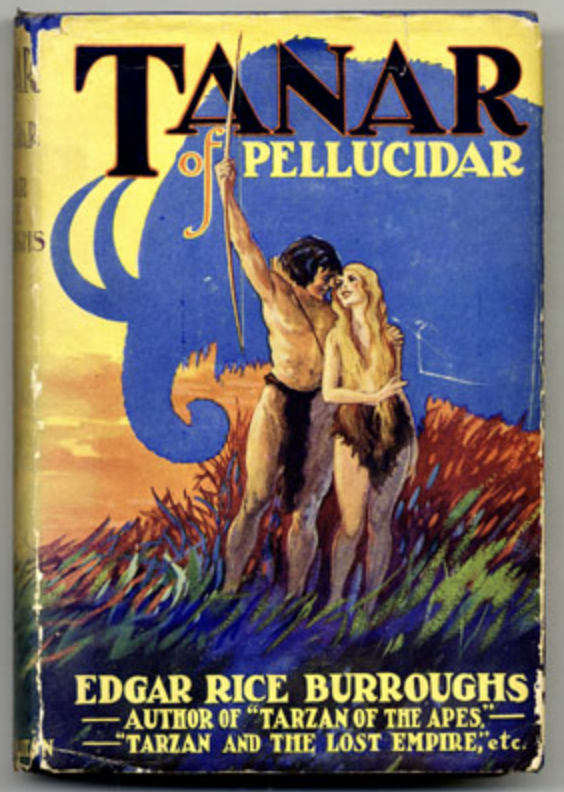

- Edgar Rice Burroughs’s Tanar of Pellucidar. The third in Burroughs’s series set in the interior world of Pellucidar. It first appeared as a six-part serial in The Blue Book Magazine from March–August 1929. It was first published in book form in 1930. The author’s friend Jason Gridley is experimenting with a new radio frequency he dubs the Gridley Wave, via which he picks up a transmission sent by scientist Abner Perry, from the interior world of Pellucidar at the Earth’s core, a realm discovered by the latter and his friend David Innes many years before inhabited by prehistoric creatures. There Innes and Perry have established an Empire of Pellucidar, actually a confederation of tribes, and attempted with mixed success to modernize the stone-age natives. Lately things have not gone well.

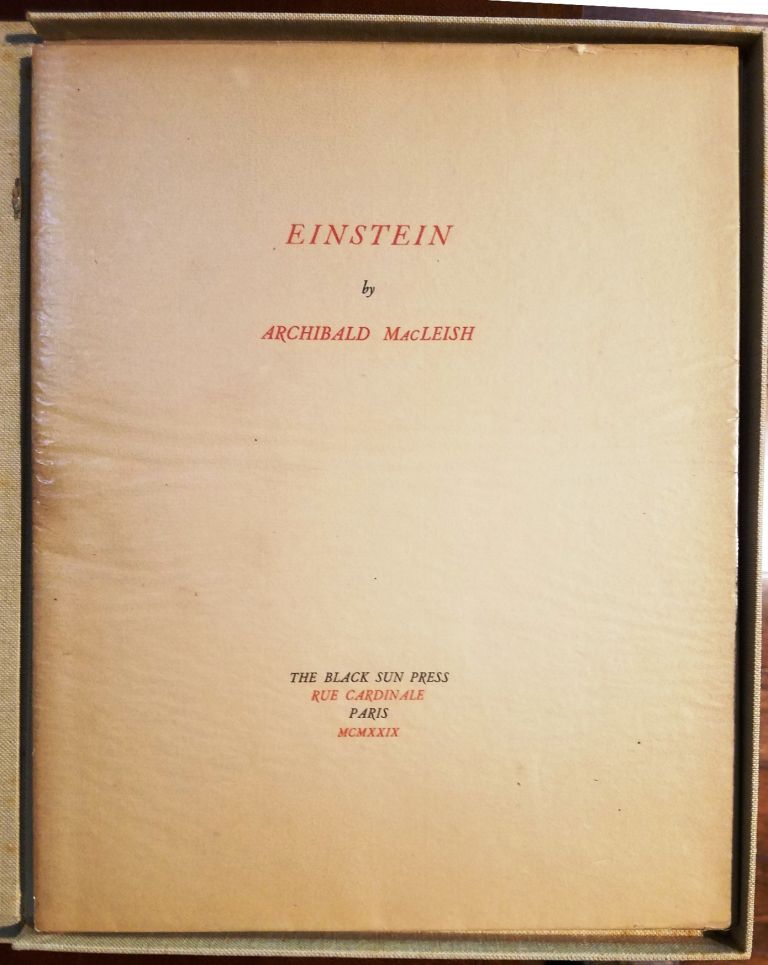

- Archibald Macleish’s poem Einstein — published separately. See 1926. Excerpted by HILOBROW.

- Edward Knoblock’s The Ant-Heap. About a scientist who creates a race of insect-beings to replace humanity.

- D.D. Sharp’s “The Eternal Man.” Collected in From Off This World: Gems of Science Fiction Chosen From “Hall of Fame Classics” (1939).

- Erle Stanley Gardner’s “The Sky’s the Limit.” Novella by the autor best known for the Perry Mason series of detective stories. Not very good sf.

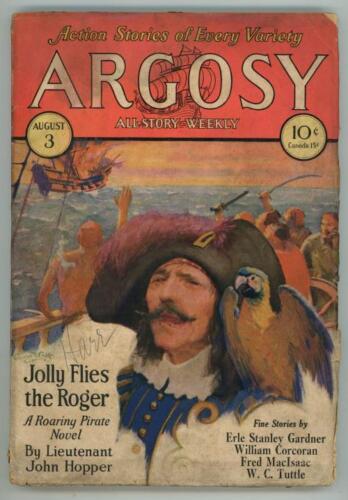

- Erle Stanley Gardner’s “Monkey Eyes” (3 August 1929 Argosy All-Story Weekly). An Apes as Human tale. Not very good sf.

- G. Peyton Wertenbaker’s “The Chamber of Life” (Amazing Stories October). First tale of virtual reality? Moskowitz cites its “stylisitc finish, sophistication and subtlety.” I like it OK.

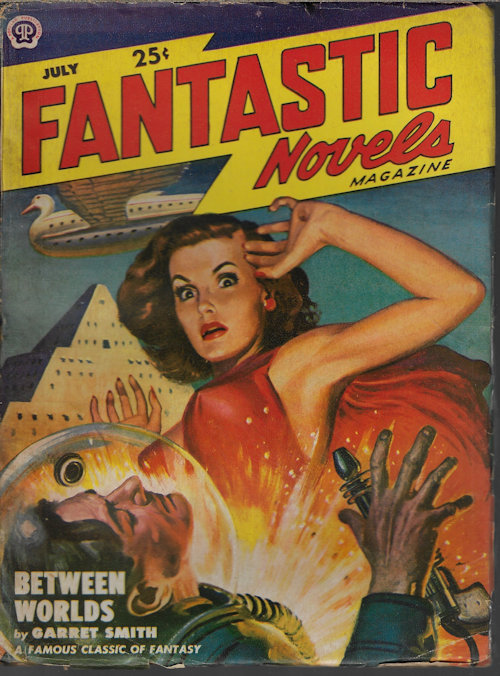

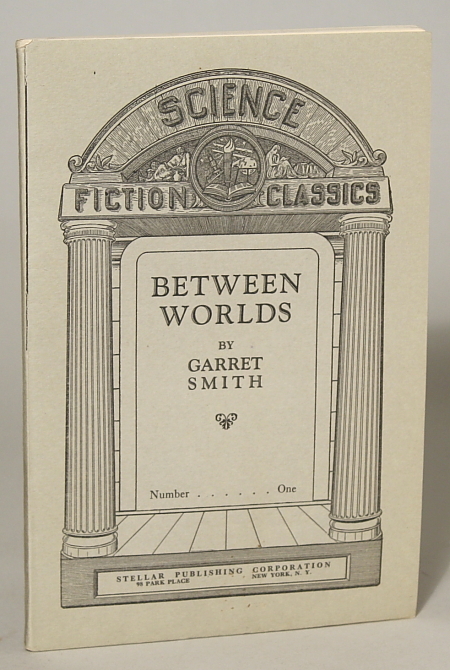

- Garret Smith’s Between Worlds. Issued as “Science Fiction Classics, Number One.” Interplanetary adventure story first published as a serial in ARGOSY, 11 October – 8 November 1919. (See 1919) Explorers from the light side of Venus venture into the dark side, where they encounter a charismatic femme fatale reminiscent of Haggard’s She, before visiting Earth to find that she and a rival have taken control of the German and Russian military machines, intent on the conquest of the world. Discussed in Anatomy of Wonder.

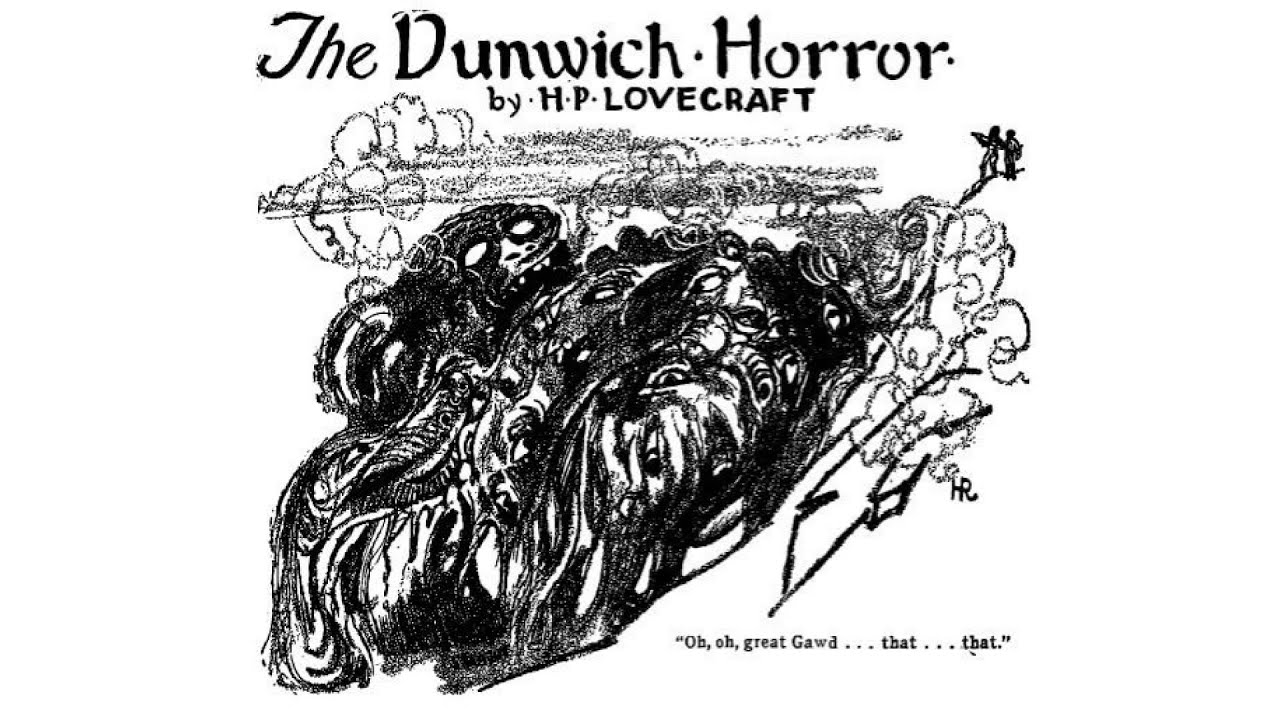

- H.P. Lovecraft’s “The Dunwich Horror” (Weird Tales). Lovecraft’s Cthulhu stories attempted to develop a distinctive species of “cosmic horror” employing premises drawn from sf: other dimensions, invasion by aliens known as the “Great Old Ones”, and interference with human cultural and physiological evolution. The overall sense of these tales is of a universe essentially horrible and hostile to humankind, a sense conveyed through a distinctive prose style. Critics generally agree on which ones are central texts, including “The Dunwich Horror.”

- Harry Bates (as “Quien Sabe?”)’s “The City of Eric.” By the author who wrote The Day The Earth Stood Still.

- Haruo Satō’s “Nonchalant Kiroku” [“An Account of Nonchalant”] (1929 in the literary magazine Kaizō). Angela Yiu of Sophia University’s “A New Map of Hell: Sato Haruo’s Dystopian Fiction” gives the following description:

The time is twenty-ninth century Japan and the place is a vertically structured metropolis that stretches from over 300 meters underground to at least thirty levels above ground. The inhabitants of the underground levels occupy dark cubicles measuring one meter in height, two-thirds of a meter in width and one-and-a-half meters in length, subsisting on piped-in gas as a substitute for food and water. The protagonist is a 15-year-old boy who, on a special charity day, climbs above ground from his habitat in the lowest level underground to experience the sights, air and sunlight of the world above…When above ground, the boy volunteers for a surgery to transform him into a rose plant. He reasons that he only has to trade in his mobility to live above ground and enjoy sunlight, air and water: mobility within the confines of a hole underground is not much to give up. As a plant, he sits on the window sill of an artists’ salon where he witnesses the whims and desires of the occupants and visitors, cinematically projected images of human forms that the plant takes to be real, and hears arguments about the various contemporary art and literary trends. Finally, another transformed human-plant in the shape of a blood-sucking leaf attaches itself to the pot of the rose plant only to then leap on to the breast of the woman who tends the rose. In shock, the woman tosses the potted rose out of the window. The story ends with the rose in free fall.

Cool recent illustration of the story here.

- Hugh Kingsmill’s The Return of William Shakespeare. Features an inspired chapter of Shakespearian criticism framed by an unconvincing science-fictional device which consigned it to shelves not visited by scholars.

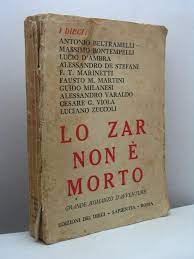

- I dieci’s Lo zar non e morto (The Tsar is not Dead). An adventurous political and espionage thriller of 1929 written by the “Gruppo de i Dieci,” a collective of Futurist and avant-garde Italian authors: Antonio Beltramelli, Massimo Bontempelli, Lucio D’Ambra, Alessandro De Stefani, Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, Fausto Maria Martini, Guido Milanesi, Alessandro Varaldo, Cesare Viola, and Luciano Zuccoli. During the New Year’s party of 1931, at the English embassy in China, the delegates of Italy, France, America, and England are informed that in Manchuria lives an old, mute man who seems the perfect double of the late Tsar Nicholas II, killed in Ekaterinburg in 1918. Is he a double wielded by dark powers? A usurper who seeks who knows what personal profit? Is he a mythomaniac aided by a prodigious resemblance? Or is he the real and authentic Tsar, who mysteriously escaped the Ekaterinburg massacre? Italy, Russia and China all race to apprehend the man: Italy in order to defeat the Bolshevik regime by putting the revived sovereign back on the throne, Russia to get rid of him permanently, and China to use him as a bargaining chip with the other two nations. This alternative-history novel is notable for the fact that one of its central characters is a woman, Oceania World, who is charged with taking the man to Europe… but then she is kidnapped! The action — driven by competing fascist and communist secret agents — takes place between China, France, Switzerland, Italy and Russia where it ends. Fun fact: In 1927 Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, drawing from the environment of fascist syndicalism, brought together “The Ten” — the authors of this novel. The goal was to present Mussolini with a “fascist epic.” Some of Marinetti’s fellow Futurists were appalled, not at his politics, but because their movement abhorred the novel as a literary form.

- Jack Williamson’s “The Alien Intelligence.” Fervently Merrittesque and imaginative. Williamson was a discovery of Gernsback’s.

- Louis Tucker’s “The Cubic City.” Collected in From Off This World: Gems of Science Fiction Chosen From “Hall of Fame Classics” (1939).

- Jack Williamson and Miles J Breuer’s The Girl from Mars. First contact story in a sober and sentimental vein. Written primarily by the younger man, following Breuer’s ideas.

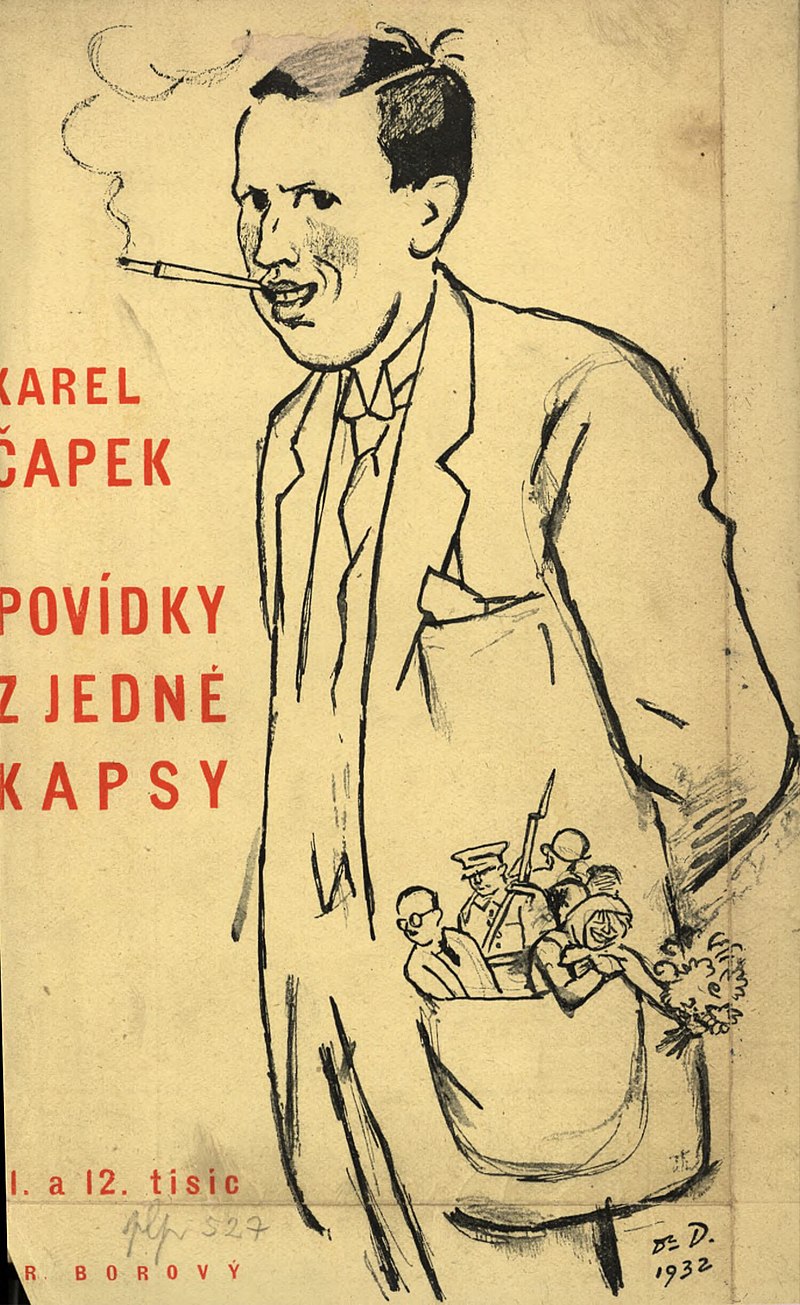

- Karel Čapek’s Povïdky z druhé kapsy [“Tales from the Other Pocket”].

- L. Taylor Hansen’s “What the Sodium Lines Revealed” (Amazing). A US anthropologist and author, Hansen published numerous sf stories and popular science articles in the pulp magazines between 1929 and 1949.

- L. Taylor Hansen’s “The Undersea Tube” (Amazing). Story of marine disaster in undersea tube. An OK story.

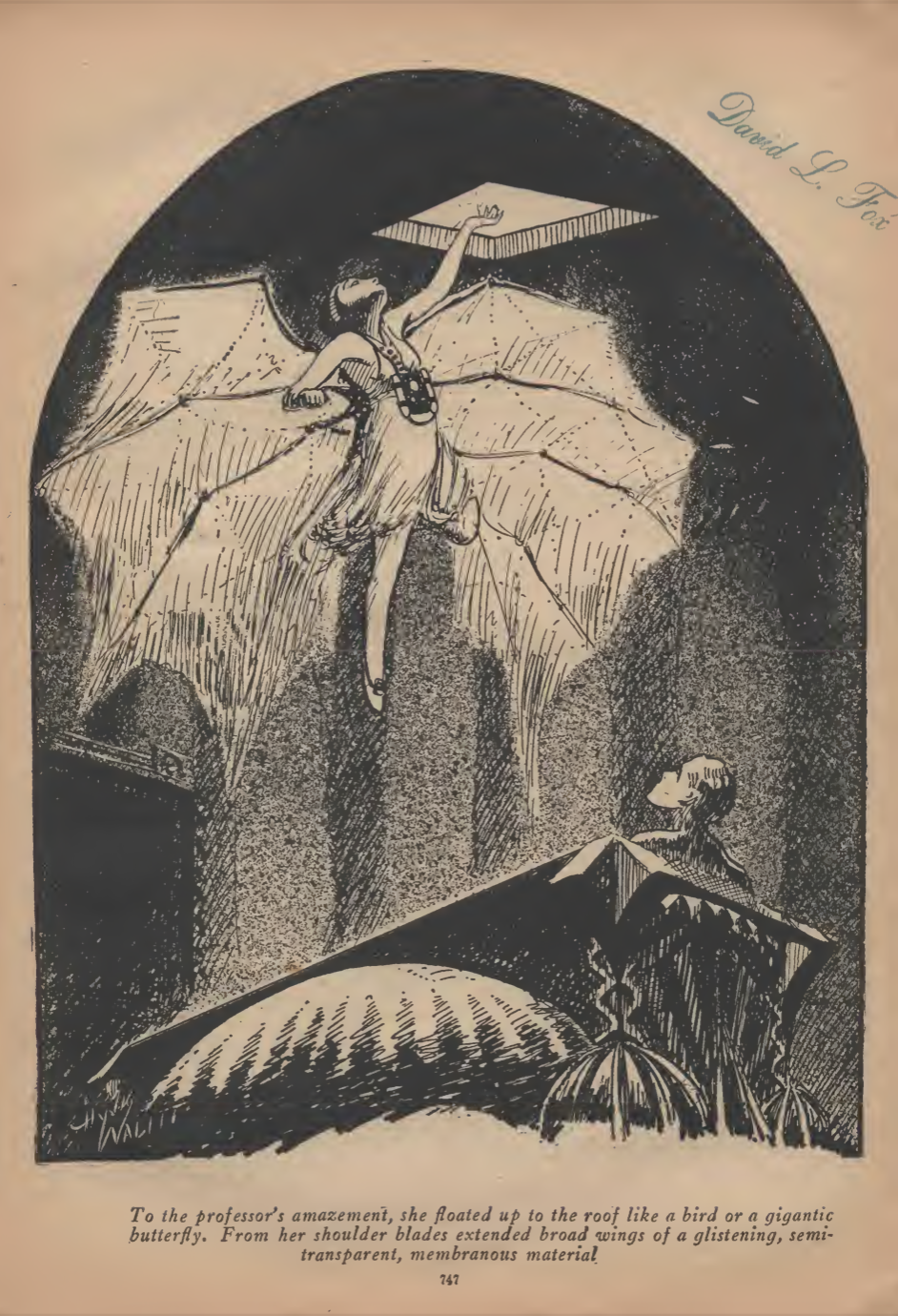

- Leslie F. Stone’s “Men with Wings” (Air Wonder Stories). Free love, utopia, alternative techniques of child rearing. John Campbell basically drove her out of the field.

- Leslie F. Stone’s “Letter of the Twenty-Fourth Century” (Amazing). Bleiler pronounced it “clever, superior work” – not much of a story, really, but predicts the fact that we never leave our houses any more.

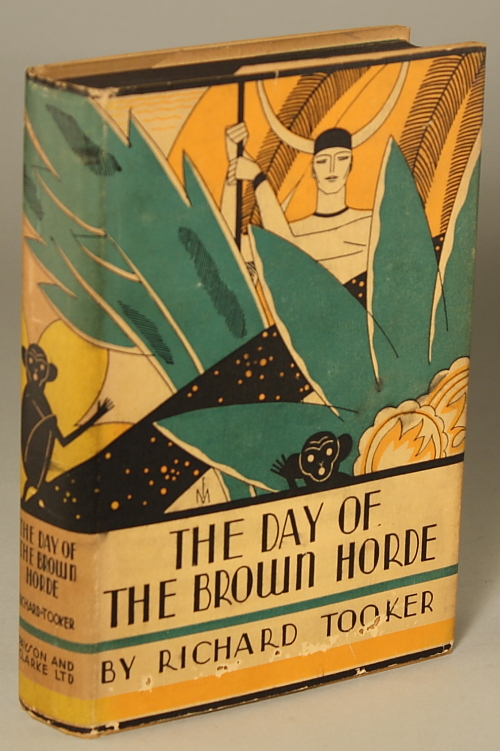

- Richard Tooker’s The Day of the Brown Horde. The author’s first book. A novel about human evolution and the survival of the fittest by an admirer of Jack London featuring cavemen who sacrifice babies to plesiosaurs and hunt bison in the valley that now forms the Gulf of California. Tooker “is best remembered for THE DAY OF THE BROWN HORDE (1929) … which deals, like most of the prehistoric-sf subgenre, with the onset of human consciousness.” – Clute and Nichols.

- Miles J. Breuer’s “The Book of Worlds” (Amazing). One of the most celebrated stories of the era, offfering 4th-dimensional visions of the future.

- Garret Smith’s Between Worlds. Issued as “Science Fiction Classics, Number One.” [Interesting to think that the idea of a science fiction classic is already happening.] Interplanetary adventure story first published as a serial in ARGOSY, 11 October – 8 November 1919. “… Explorers from the light side of Venus venture into the dark side, where they encounter a charismatic femme fatale reminiscent of Haggard’s She, before visiting Earth to find that she and a rival have taken control of the German and Russian military machines, intent on the conquest of the world. “Smith was perhaps the most interesting of all the writers producing SF for the non-specialist pulps, and his stories should have been more widely reprinted; the most extravagant is the serial ‘After a Million Years’ (ARGOSY, 1922).” – Anatomy of Wonder. See 1919.

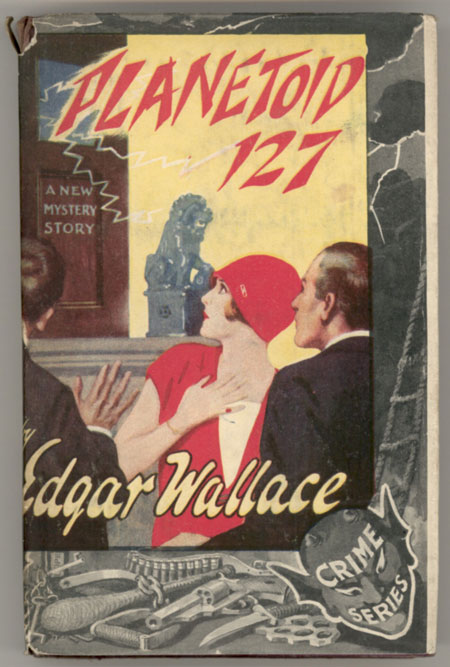

- Edgar Wallace’s Planetoid 127. A short novel of communication by radio with another world on the other side of the sun in earth’s orbit. Wallace, who died in 1932, is best known for his many thrillers, though he was also variously active as an sf writer from the beginning of his active career. Fun fact: While working in Hollywood, Wallace assisted on the screenplay of King Kong (1933).

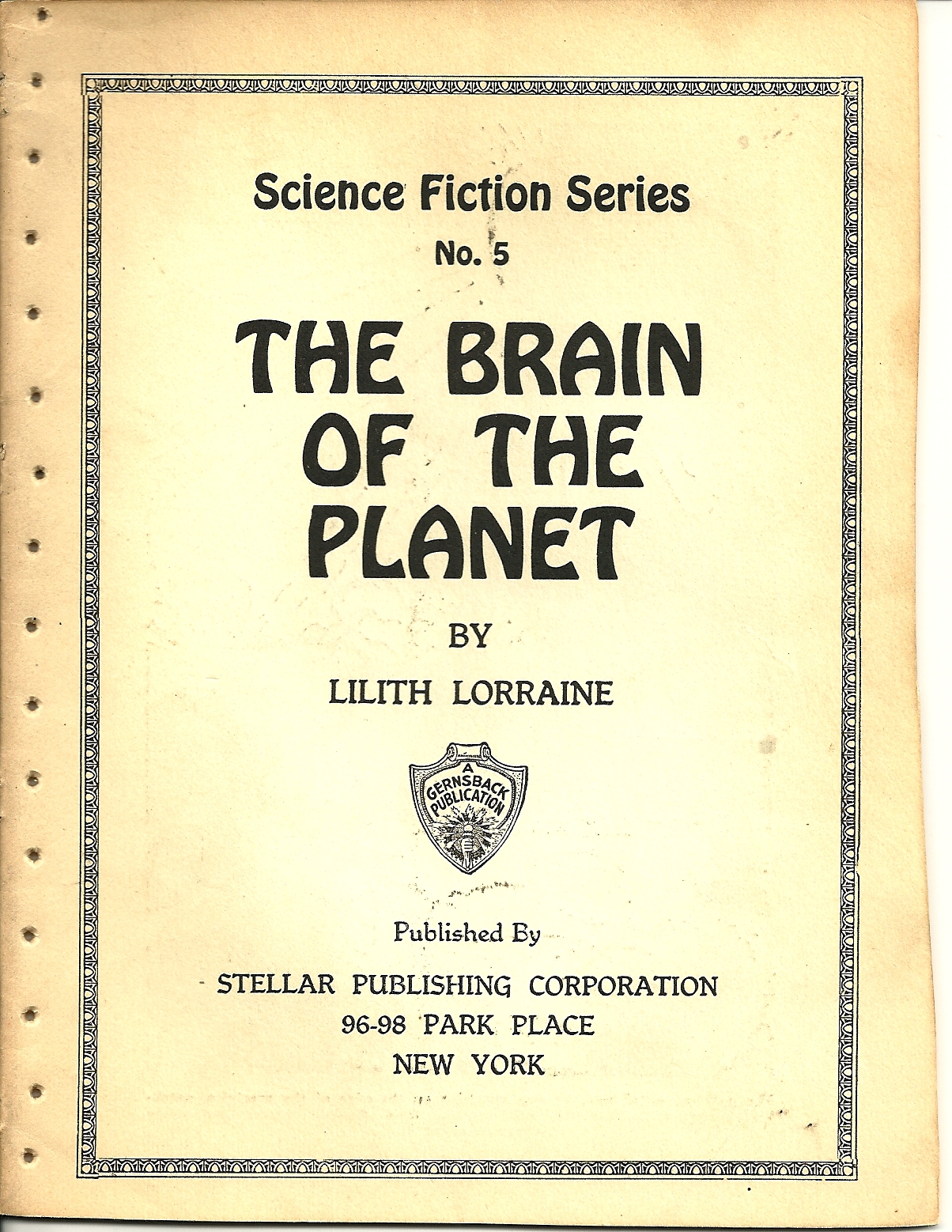

- Lilith Lorraine’s The Brain of the Planet. Lilith Lorraine was one of at least five pseudonyms of Mary Maude Wright (1894-1967), US poet, editor, radio lecturer and author, who regularly published sf in the 1930s pulp magazines. The Brain of the Planet (1929 chap), from Hugo Gernsback’s Science Fiction Series, portrays a feminist utopia founded after a socialist revolution has released women from the necessity of marriage.

- Maurice Renard’s Le Carnaval du mystère [“The Carnival of Mystery”]. Includes many fine stories, mostly extremely short, on a great variety of sf themes: clones, invisibility, time travel, cyborgs, gravity, time paradoxes, eschatology and, especially and often, altered modes of perception.

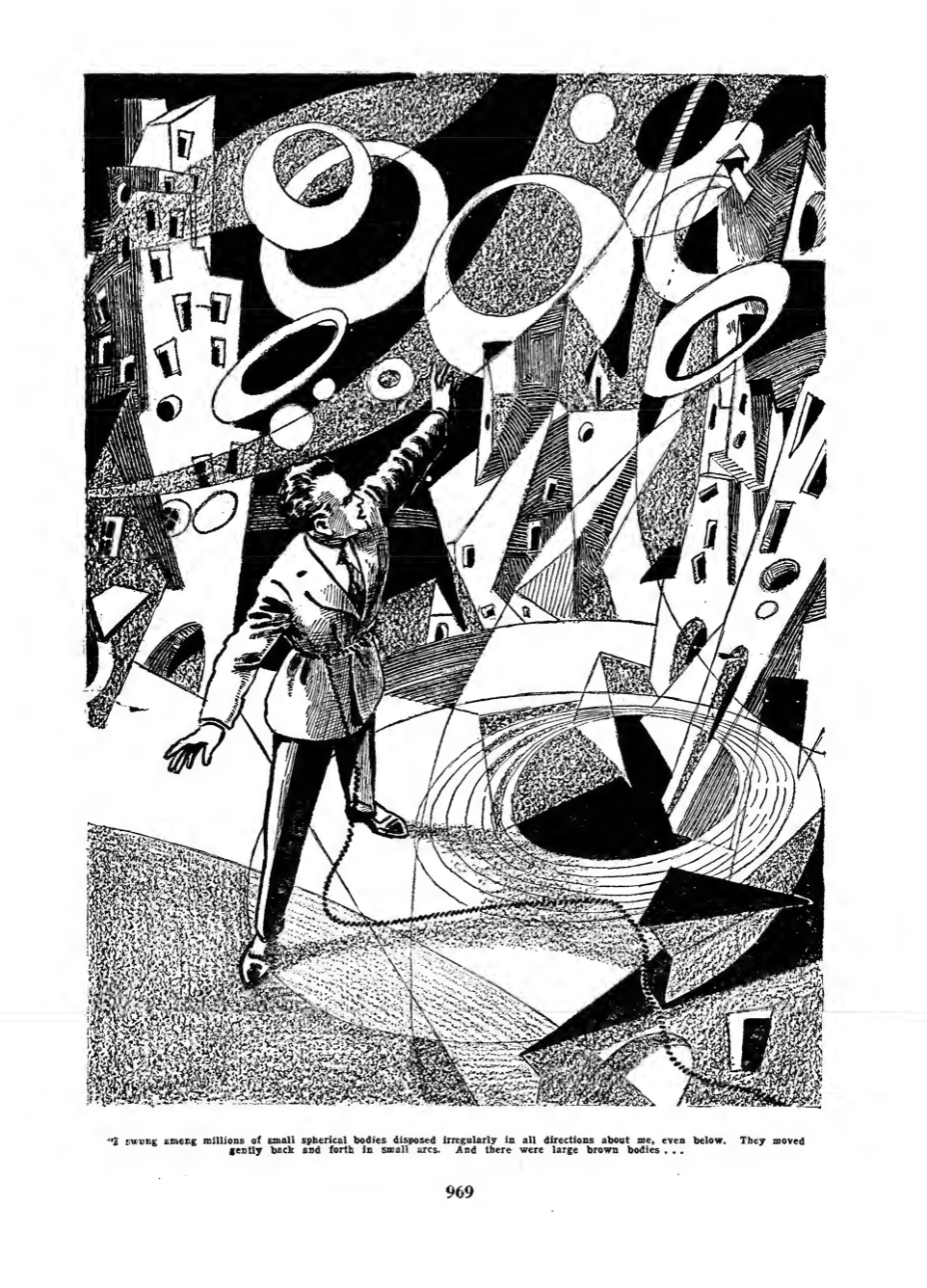

- Miles J. Breuer’s “The Captured Cross-Section” (Amazing Stories February 1929). Weird Cubist parable — I like it.

- Miles J. Breuer’s “Rays and Men” (Amazing). Supposedly an outstanding work.

- Minna Irving’s “The Moon Woman” (Amazing 1929 – November). Considered an outstanding story. Female author. Women from the Moon take over Earth and improve it

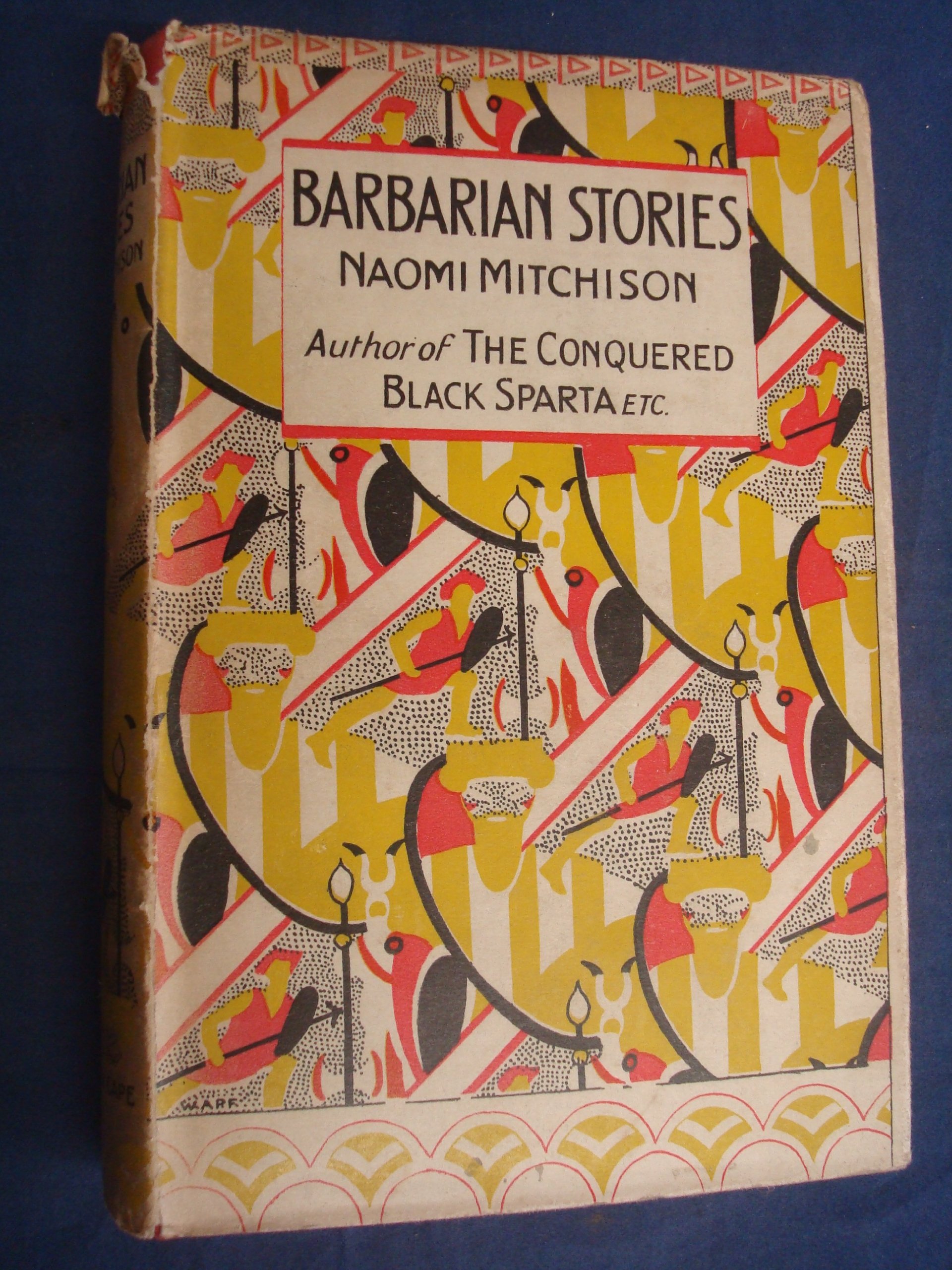

- Naomi Mitchison’s “The Goat: Cardiff AD 1935.” About an impoverished near-future world where a rich person is sacrificed annually, in her 1929 collection Barbarian Stories. Naomi Mitchison (1897–1999) was a Scottish novelist and poet, and JBS Haldane’s sister.

- Neil Bell’s “The Mouse.” I think it was in his 1929 collection Animal Tales. Bell would become a prolific author of sf and horror.

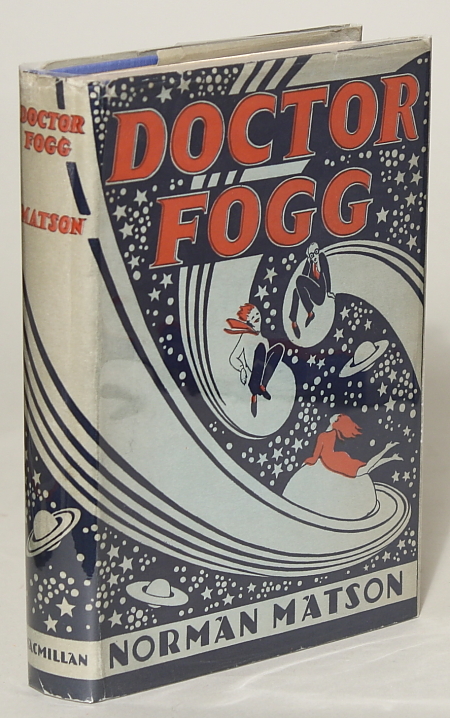

- Norman Matson’s Doctor Fogg. Bittersweet satire of communication with other planets. One of my favorite cover illustrations from the period.

- Otto Willi Gail’s “The Missing Clock Hands.” A clumsy story about an inadvertent time traveler who recounts his sorry history before an incredulous judge. Collected in The Black Mirror (Wesleyan).

- Ray Cummings’s “The Shadow Girl.” Called his best time travel story.

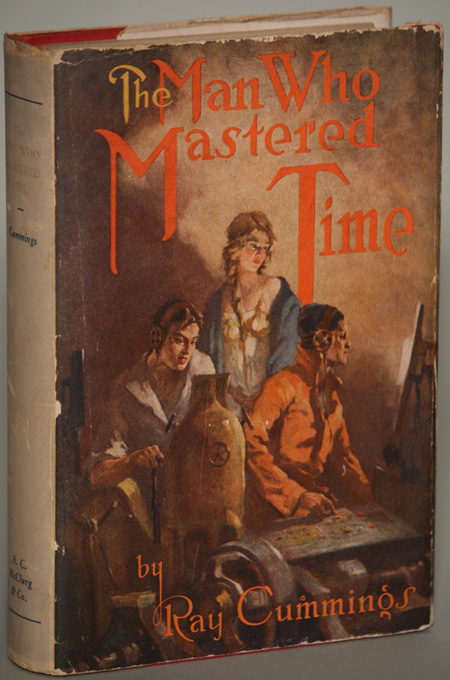

- Ray Cummings’s The Man Who Mastered Time. Travel by time machine to earth’s far future. “Completes the trilogy of my tales of Matter, Space, and Time [The Girl in the Golden Atom and “The Fire People” dealing with the first two matters, respectively].” – Ray Cummings.

- Ray Cummings’s “Sea Girl” (2 February-6 April 1929 Argosy All-Story Magazine). In which a humanoid race from under the sea threatens 1990s-era humankind.

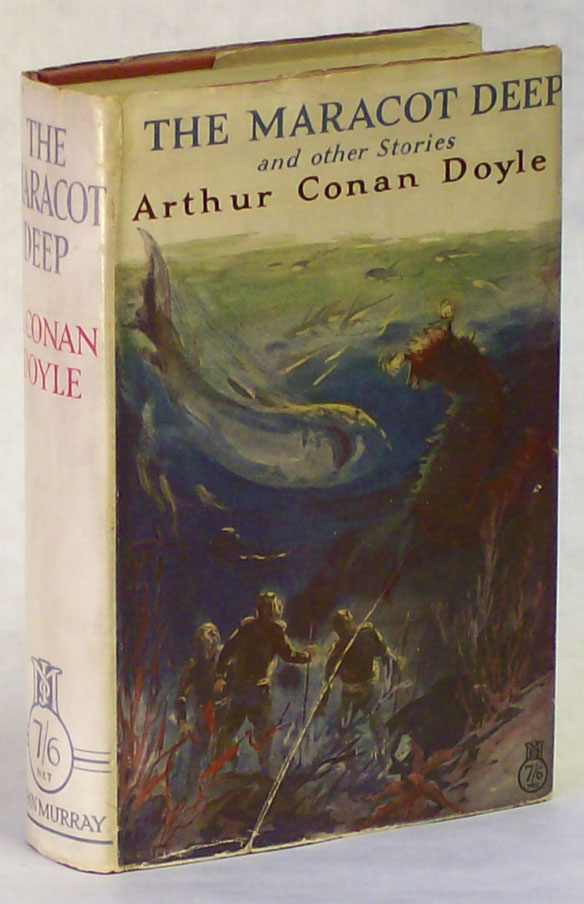

- Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Maracot Deep & Other Stories. Collects the title novella, “The Story of Spedegues’s Dropper,” and two Professor Challenger stories, “The Disintegration Machine” and “When the World Screamed.”

- Raymond Z. Gallun’s “The Space Dwellers” and “The Crystal Ray.” Gallun began publishing sf stories at the age of eighteen in November 1929, with “The Space Dwellers” in Wonder Stories and “The Crystal Ray” in Air Wonder Stories.

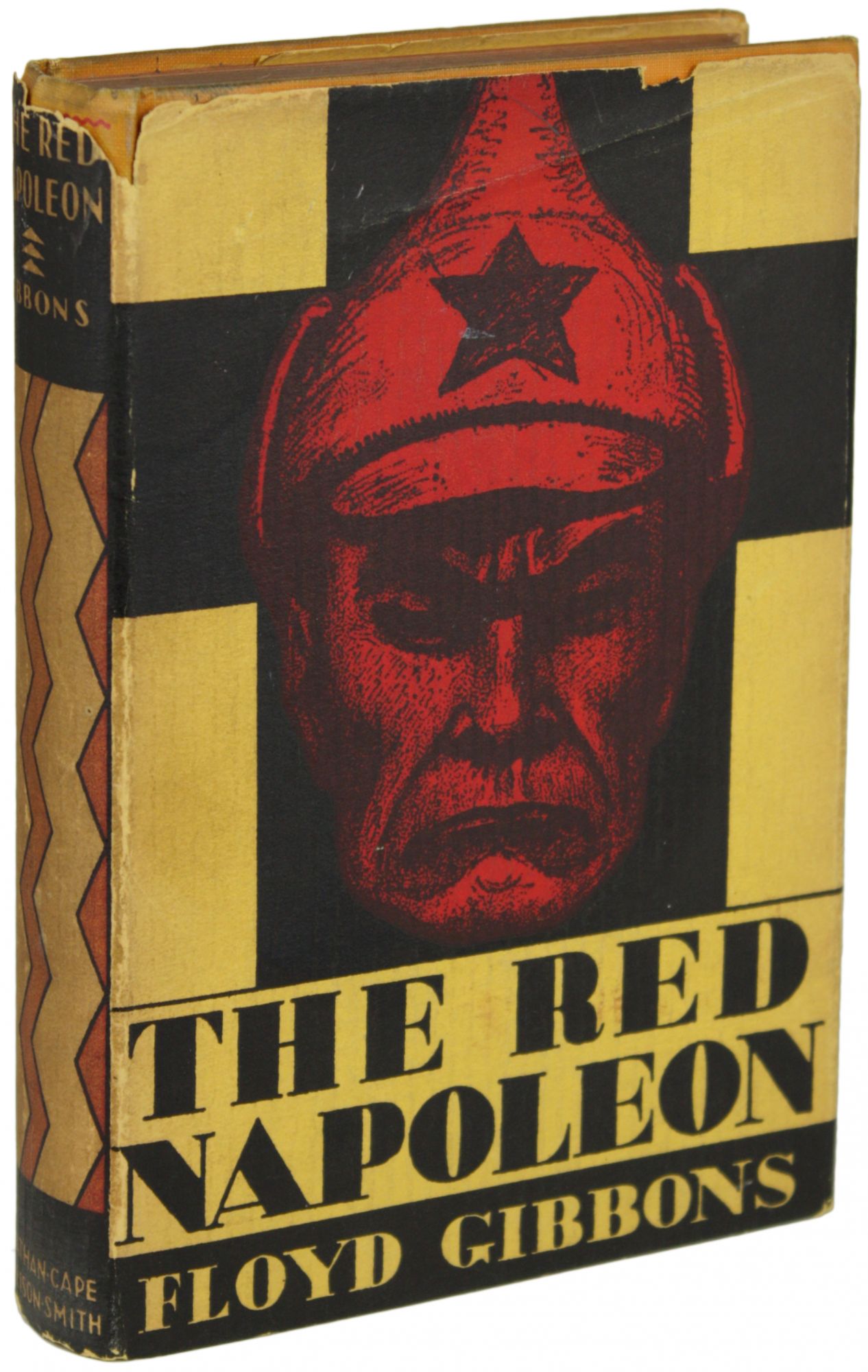

- Floyd Gibbons’s The Red Napoleon. A yellow/red peril future war novel whose main action is set in the U.S.S.R., London, and Mexico during the period of 1932-1936. AA communist Tartar-Mongol nearly succeeds in subjugating the world, only to be defeated at the Battle of Jamaica. “Because of the writer’s intimate knowledge of war reportage, one of the best imaginary war novels, despite wooden characters and an unconvincing American victory.” – Bleiler.

- Robert Graves’s “Welsh Incident.” A poem about indescribable sea monsters who — one imagines — might be aliens.

- Robert Graves’s “The Shout,” a sophisticatedly recursive Club Story assembled with other work, including the anti-religion fantasy satire “Autobiography of Baal”, in But It Still Goes On: An Accumulation (coll 1930); it was later filmed as The Shout (1978) directed by Jerzy Skolimowski.

- Miles J. Breuer’s “The Appendix and the Spectacles,” “The Captured Cross-Section,” and “The Book of Worlds” (all published in Amazing). In Time Machines, Ashley calls this an interesting trilogy about other dimensions.

- S. Fowler Wright’s “P.N. 40.” Set in nightmarish future where scientism has made life frightful.

- S.P. Meek’s “Futility” (Amazing). One of the most celebrated stories of the era; Bleiler calls its Meek’s best story. About a predictograph.

- Sax Rohmer’s The Emperor of America. In which a criminal gang, armed with various inventions, attempts to gain control of the entire country from its underground base beneath Manhattan.

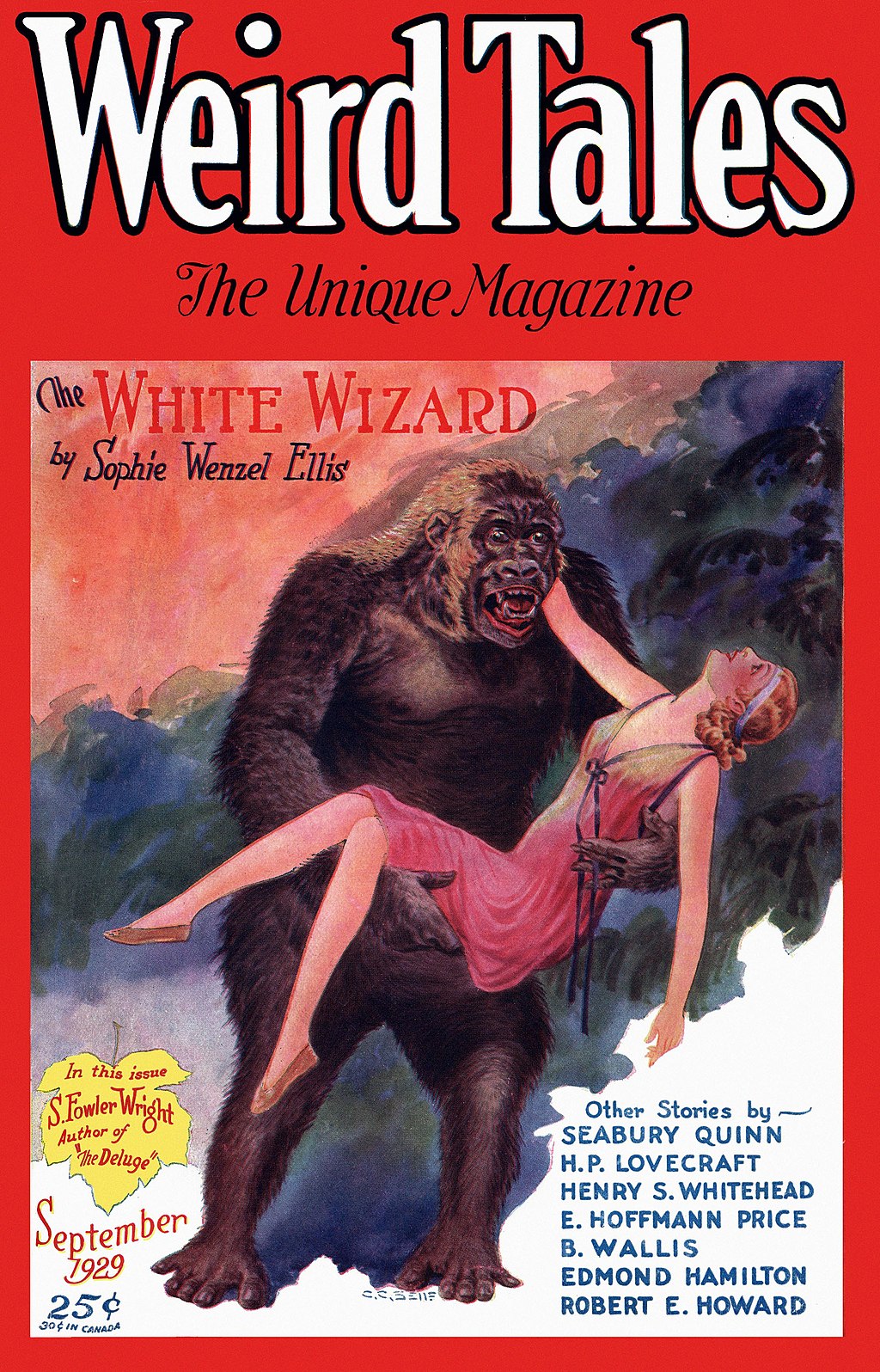

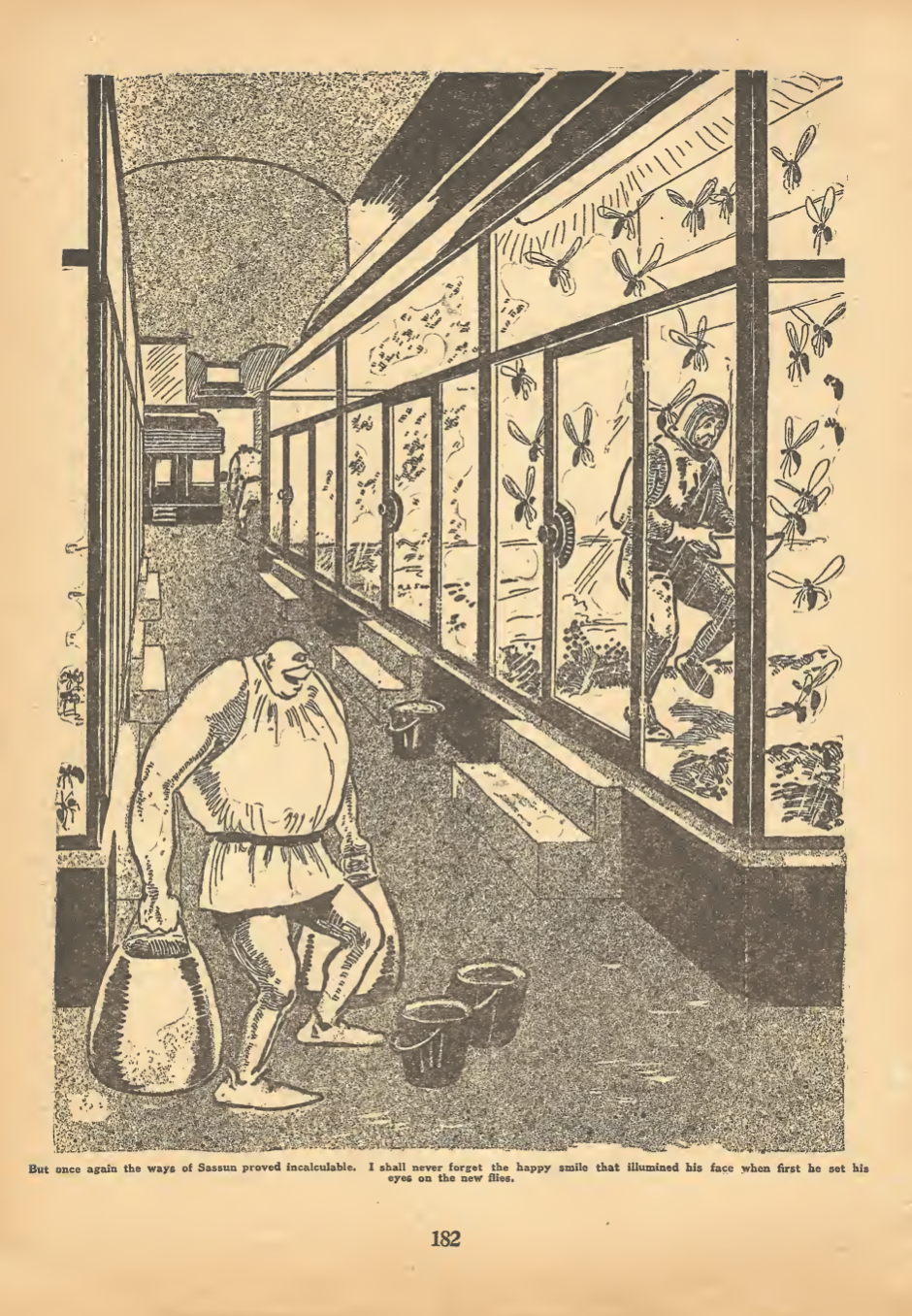

- Sophie Wenzel Ellis’s “The White Wizard.” Monster story in Weird Tales.

- Stanton A. Coblentz’s After 12,000 Years (in Amazing). Bizarre and interesting, tongue in cheek. It has been described as his best, wildest, most imaginative novel. The novel concerns Henry Merwin, who after taking part in an experiment finds himself 12,000 years in the future. Taken captive by a giant race, he is forced to care for their insect pets. He falls in love with a fellow prisoner, Luellen, but his captors will not allow them to marry. Instead he is forced to go to war with his insect charges. The insects eventually grow to such a size that they take over much of the earth.

- Wallace G. West’s “The Last Man” (Amazing). Much reprinted, considered controversial and thought-provoking at the time. Atavastic, women don’t need men. I kinda like it — ends like Blade Runner ends. Appears in the 1943 anthology The Pocket Book of Science Fiction, edited by Donald A. Wollheim. Fun facts:

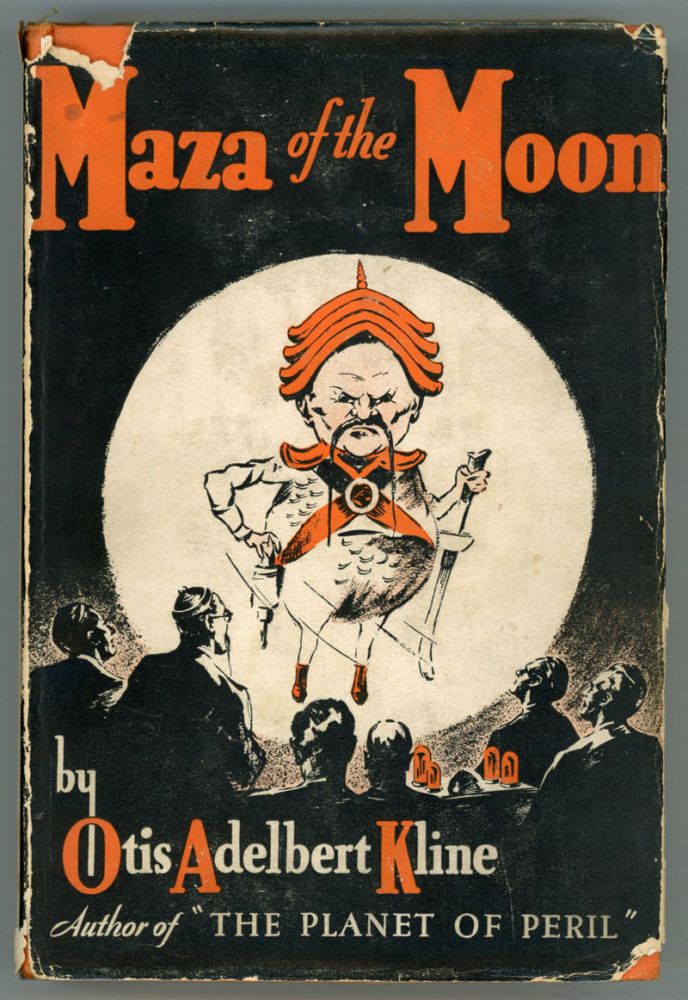

West was a US lawyer, author, public-relations man and pollution-control expert who began publishing short stories with “Loup-Garou” in Weird Tales for October 1927 and sf with “The Last Man” in Amazing from February 1929, thereafter appearing fairly regularly in the magazines until the late 1960s. - Otis Adelbert Kline’s Maza of the Moon. The author’s second book. A rousing space opera, first published as a four-part serial in Argosy, 21 December 1929 – 11 January 1930, in which earth is threatened with destruction by the inhabitants of the moon. “Interplanetary war and the Yellow Peril… Astonishing that Argosy would print this.” – Bleiler.

ALSO: Einstein’s “Unified Field Theory.” The “Vienna Circle” formed by Carnap, Hahn, etc. José Ortega y Gasset’s The Revolt of the Masses. Julian Huxley and G. P. Wells’s The Science of Life. Faulkner’s The Sound and the Fury; Hemingway’s A Farewell to Arms; Richard Hughes’s A High Wind in Jamaica; Woolf’s A Room of One’s Own; Dashiell Hammett’s The Dain Curse. Talkies kill silent films. “Black Friday” in US — Stock Exchange collapses. Tarzan of the Apes adapted into newspaper strip form with illustrations by Hal Foster; the strip Buck Rogers also first appears. “Aeropainting” was launched in a manifesto of 1929, Perspectives of Flight, signed by the Italian Futurists Benedetta, Depero, Dottori, Fillìa, Marinetti, Prampolini, Somenzi and Tato (Guglielmo Sansoni). The artists stated that “The changing perspectives of flight constitute an absolutely new reality that has nothing in common with the reality traditionally constituted by a terrestrial perspective.” Fritz Lang’s f movie Frau im Mond (Woman in the Moon) introduces the idea of counting down the time to a rocket launch.

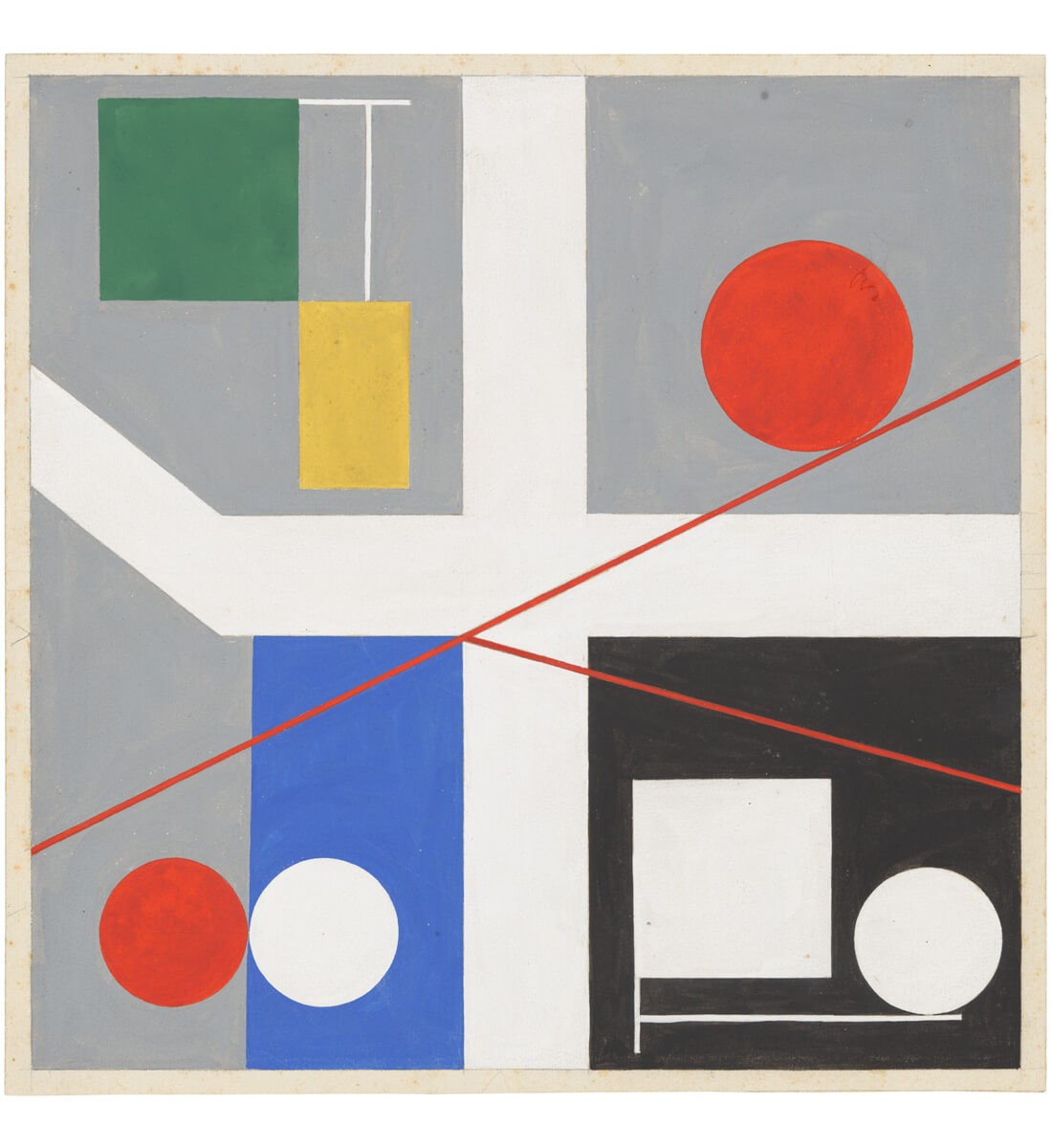

In 1929, Hans Arp and Sophie Taeuber-Arp left Zurich for Paris, Europe’s more fashionable art hub, and they soon fell in with a group of artists similarly exploring non-figurative art, including Joan Miró, Wassily Kandinsky, and Marcel Duchamp. Taeuber-Arp joined two artists groups: Cercle et Carré and Abstraction-Création. She also edited the short-lived Constructivist review Plastique/Plastic.

During that period she created some of her strongest work in abstract painting and painted reliefs. The works almost all feature perfect circular and rectangular forms depicted in primary colors cast against monochromatic backgrounds. The mood is calm, uncluttered and the focus is on color.

MORE RADIUM AGE SCI FI ON HILOBROW: HiLoBooks homepage! | What is Radium Age science fiction? |Radium Age 100: 100 Best Science Fiction Novels from 1904–33 | Radium Age Supermen | Radium Age Robots | Radium Age Apocalypses | Radium Age Telepaths | Radium Age Eco-Catastrophes | Radium Age Cover Art (1) | SF’s Best Year Ever: 1912 | Radium Age Science Fiction Poetry | Enter Highbrowism | Bathybius! Primordial ooze in Radium Age sf | War and Peace Games (H.G. Wells’s training manuals for supermen) | Radium Age: Context series | J.D. Beresford | Algernon Blackwood | Edgar Rice Burroughs | Karel Čapek | Buster Crabbe | August Derleth | Arthur Conan Doyle | Hugo Gernsback | Charlotte Perkins Gilman | Cicely Hamilton | Hermann Hesse | William Hope Hodgson | Aldous Huxley | Inez Haynes Irwin | Alfred Jarry | Jack Kirby (Radium Age sf’s influence on) | Murray Leinster | Gustave Le Rouge | Gaston Leroux | David Lindsay | Jack London | H.P. Lovecraft | A. Merritt | Maureen O’Sullivan | Sax Rohmer | Paul Scheerbart | Upton Sinclair | Clark Ashton Smith | E.E. “Doc” Smith | Olaf Stapledon | John Taine | H.G. Wells | Jack Williamson | Stanisław Ignacy Witkiewicz | S. Fowler Wright | Philip Gordon Wylie | Yevgeny Zamyatin