IN CAHOOTS (2)

By:

October 18, 2022

Second in a series of posts via which HILOBROW’s Josh Glenn offers anecdotes and advice from his own creative career.

IN CAHOOTS: GOING INDIE | MATERIAL CULTURE | COMMUNITY BUILDING | WALKING THE TIGHTROPE | OBJECT-ORIENTED | PARTNERING | CAMARADERIE.

Though I’ll return to these themes in the next installment, the current IN CAHOOTS installment discusses neither living a creative life, nor collaboration as one key aspect of doing so. Instead, I want to talk a little bit about my approach to material culture — because it’s one of the threads that knits up the ravell’d sleeve of my so-called career.

I’m fascinated by material culture — things, objects, and artifacts, including what Marx called “commodities,” which is to say things, objects, and artifacts the value of which is not intrinsic but which has been infused into them artificially by the market. To some extent, I have been influenced by my mother’s love of yard sales and thrift stores, which I inherited. But I’m also fascinated by marketing and branding — i.e., the means by which value is infused into things, objects, and artifacts. My initial influence here was Roland Barthes’s Mythologies. Unlike Barthes, however, who was engaged in ideologiekritik, my angle is a pseudo-anthropological one. In addition to being fascinated by the ideologies lurking behind advertising, I am simply fascinated — in the way that an alien visitor might be — by the whole phenomenon of marketing and branding.

I was also intrigued by the theorizing of Michel de Certeau — a French scholar whose work combined history, psychoanalysis, philosophy, and the social sciences as well as hermeneutics, semiotics, ethnology, and religion. His 1980 book The Practice of Everyday Life examines the ways in which we individualize mass culture, altering things, from utilitarian objects to street plans to rituals, laws and language, in order to make them our own. Unlike many other books about mass culture, it is refreshingly unsanctimonious. With no clear understanding of the activity of “re-use,” de Certau warns, social scientists and social critics can only conceive of people who are non-creators and non-producers in an elitist, sanctimonious fashion — i.e., as passive consumers, dupes.

At the risk of sounding like a contributor to Reason magazine: You know who perceives the mass of ordinary people as passive consumers and dupes? Elitist snobs, con artists and would-be dictators. Think about it.

My initial fascination with objects and marketing took place during a moment when, among members of my (1964–1973) generation, these were deeply uncool things with which to be fascinated. Movies that warned about the moral peril of selling out, for example, included (off the top of my head): Say Anything… (1989), Slacker (1990), Wayne’s World (1992), Singles (1992), Dazed and Confused (1993), Reality Bites (1994), Clerks (1994), Empire Records (1995), Trainspotting (1996), Jerry Maguire (1996), Good Will Hunting (1997), Grosse Point Blank (1997), The Truman Show (1998), The Big Lebowski (1998), Fight Club (1999), Election (1999), The Matrix (1999), Being John Malkovich (1999), and High Fidelity (2000). In fact, if it weren’t for Paul Thomas Anderson, Martin Scorsese, Quentin Tarantino, and Adam Sandler (the anti-John Cusack), every movie from the 1990s would have been a selling-out morality play.

Selling out became, for us, a generational neurosis whose effects continue to linger today.

To be clear, I didn’t want to go into business, or marketing, or sales — and I haven’t done so since. I was simply fascinated with the question of how branding, marketing, and product and pack design work. Why are we wised-up, enlightened, supposedly modern types so prone to perceiving unearned value in commodities, and to investing inanimate objects with emotion and meaning?

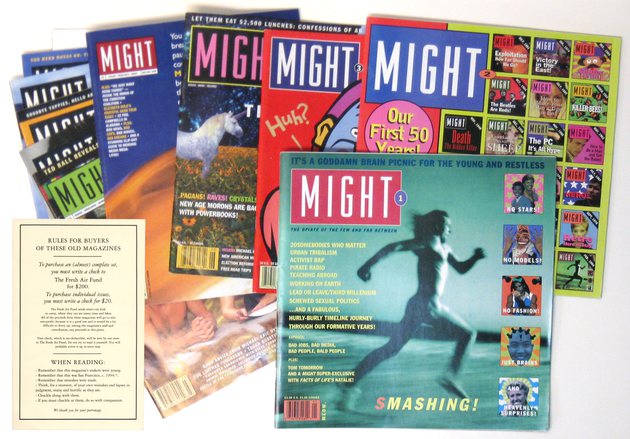

When Dave Eggers’ glossy magazine Might appeared in 1994 (the first year of the cultural era that we think of as the Nineties [1994–2003], as opposed to the calendrical 1990s), it simultaneously mocked advertising conventions while running hip Tanqueray ads. I suddenly understood Adorno’s off-the-cuff comment (in a Minima Moralia entry whose title means “to subdue us”) about “millionaire magazines.” Middlebrow anti-materialism seeks to have its cake and eat it too; David Brooks would call this “bourgeois bohemianism.”

So in a 1995 issue of Hermenaut, I offered an articulation of my own anti-antimaterialist proclivities. “Going to Disney World to drop acid and goof on Mickey isn’t revolutionary; going to Disney World in full knowledge of how ridiculous and evil it all is and still having a great innocent time, in some almost unconscious, even psychotic way, is something else altogether,” I wrote — firmly distancing my own position from an Eggers-esque, having-it-both-ways “ironic consumption,” i.e., goofing on Mickey, say, while still visiting Disney World. “This is what [Michel] de Certeau describes as ‘the art of being in-between,'” I proposed, “and this is the only path of true freedom in today’s culture.”

In Naomi Klein’s anti-material-culture book No Logo: Taking Aim at the Brand Bullies (1999), the above passage from Hermenaut would be quoted as an example of… ironic consumption. *Sigh.*

I agree with Klein that the companies closing their factories and outsourcing the production of their products to contractors and subcontractors — late capitalism, let’s call it — has been devastating to the working and middle classes. But the notion that corporations moved in this direction because they’d decided to “produce brands, not products” is a ridiculous one. I’m not persuaded that she even agrees with her own thesis; it’s bullshit, in other words — words uttered by a con artist in order to get your attention while distracting you from what they’re really doing.

Klein’s audience shares an elitist distaste for marketing, so she cleverly capitalized on that in order to get them to pay attention when — magician-like — she went on to discuss how products are made in the deregulated global supply chain, industrial agriculture and commodity prices, free-trade deals and the World Trade Organization. Bait-and-switch stuff — which may have worked to sell copies of the book, but which resulted in symbolic gestures (Klein would later express admiration for the way in which a character in William Gibson’s 2003 novel, Pattern Recognition, had the buttons on her Levi’s jeans ground smooth to remove any corporate markings) rather than any deep structural change. One thinks of Upton Sinclair’s complaint about the Pure Food and Drugs Act of 1906, which was passed in no small part thanks to public outrage inspired by his 1905–1906 novel The Jungle, which was intended instead to raise awareness about harrowing working conditions in Chicago’s meatpacking industry: “I aimed at the public’s heart and by accident I hit it in the stomach.” Except Klein’s mis-aim — at branding, instead of late capitalism — was entirely her decision.

This 2015 New York Magazine feature by Jonathan Chait takes Klein to task for her “fervently ideological, anti-empiricist style” and her “absolutist ideological reasoning.” Although I sympathize with her political and economic ends, Klein’s means are all too similar to those of the far-right ideologues against whom she’s pitted herself.

Eggers, too, has become an avatar of anti-materialism — to the detriment of his prose style. This 2022 n+1 essay is a satisfying response to Eggers’s latest anti-materialist tome, a sequel to his 2013 novel The Circle. “Eggers is working through a set of specific and reasonable anxieties about Amazon: its chillingly intimate knowledge of users who leave their Echo devices on; its hold over independent publishing and bookselling and the reading experiences those industries promote,” etc., writes Lisa Borst. “But Eggers’s shots at the platform, which is really one of the largest and easiest targets of critique in the history of capitalism, rarely seem precisely calibrated. What they are is sanctimonious and long.” Like Borst, I don’t disagree with Eggers that Amazon is a deeply problematic company that is making our lives worse. My issue is with his elitist, sanctimonious assumption that most people are passive consumers and dupes.

“Everyone should be forced to read Dave Eggers’s The Circle before buying an Apple Watch,” Klein tweeted in 2013. “Really.” Sure, don’t buy an Apple Watch, but that “really” — brrr! Talk about ideological absolutism. Klein and Eggers, who warn of apocalyptic, dystopian crisis in all their writings, seem all too ready to assume emergency dictatorial power.

To quote yet another French anthropologist, sociologist and philosopher, Bruno Latour (who died earlier this month), we have never been modern.

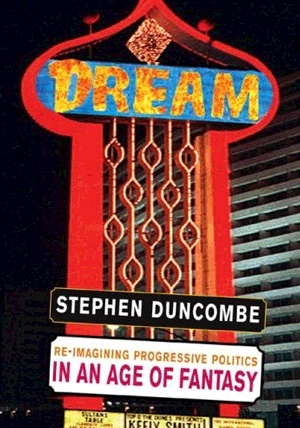

This is what fascinates me — the ongoing failure of the Enlightenment program — particularly as this fact is evidenced by our emotional connection to objects and brands. Enlightened liberal types are grossed out by the fact that we have never been modern; theirs is an aesthetic response, one which produced sanctimoniousness and thus prevents them from digging deeper into this uncanny phenomenon. (See Stephen Duncombe’s Dream for a far more articulate expression of what I’m saying here.) I want to understand not just the “what” of material culture, but the “how”; how is that we find value and meaning in stuff?

Latour, by the way, was dedicated to exploring the notion that facts do not exist outside of society, but rather are generated and advanced within dense networks of people, ideas and objects. A de-mystifying notion that serves as a much-needed corrective to absolutist ideology and sanctimony.

I mentioned Barthes, above. It was his conviction that semiotics — a social science that analyze not just what things mean, in a particular culture, but how they mean what they mean — offered the best means of exploring the sorts of questions I’d begun asking. In the late 1990s and early 2000s — when Hermenaut was going bankrupt — I found my way into the arcane world of applied semiotics. Although this wasn’t the same thing as going into marketing, it’s marketing-adjacent. Which would no doubt have felt like selling out, had I ever “bought in” to begin with. This move would provide a lesson in the art of being in-between — which can be a painful practice, since it means pursuing neither one passion nor another, but both at once.

Next time: COMMUNITY BUILDING

MORE FURSHLUGGINER THEORIES BY JOSH GLENN: SCHEMATIZING | IN CAHOOTS | JOSH’S MIDJOURNEY | POPSZTÁR SAMIZDAT | VIRUS VIGILANTE | TAKING THE MICKEY | WE ARE IRON MAN | AND WE LIVED BENEATH THE WAVES | IS IT A CHAMBER POT? | I’D LIKE TO FORCE THE WORLD TO SING | THE ARGONAUT FOLLY | THE PERFECT FLANEUR | THE TWENTIETH DAY OF JANUARY | THE REAL THING | THE YHWH VIRUS | THE SWEETEST HANGOVER | THE ORIGINAL STOOGE | BACK TO UTOPIA | FAKE AUTHENTICITY | CAMP, KITSCH & CHEESE | THE UNCLE HYPOTHESIS | MEET THE SEMIONAUTS | THE ABDUCTIVE METHOD | ORIGIN OF THE POGO | THE BLACK IRON PRISON | BLUE KRISHMA | BIG MAL LIVES | SCHMOOZITSU | YOU DOWN WITH VCP? | CALVIN PEEING MEME | DANIEL CLOWES: AGAINST GROOVY | DEBATING IN A VACUUM | PLUPERFECT PDA | SHOCKING BLOCKING.