RADIUM AGE: 1926

By:

October 16, 2022

A series of notes towards a comprehensive account of the science fiction genre’s Radium Age (1900–1935). These notes are very rough-and-ready, and not properly attributed in many cases. More information on Josh’s ongoing efforts here and here.

RADIUM AGE TIMELINE: [1900 | 1901 | 1902 | 1903] | 1904 | 1905 | 1906 | 1907 | 1908 | 1909 | 1910 | 1911 | 1912 | 1913 | 1914 | 1915 | 1916 | 1917 | 1918 | 1919 | 1920 | 1921 | 1922 | 1923 | 1924 | 1925 | 1926 | 1927 | 1928 | 1929 | 1930 | 1931 | 1932 | 1933 | [1934 | 1935]. (The brackets, here, indicate “interregnum” years — i.e., periods of overlap between sf’s Radium Age and its Scientific Romance and so-called Golden Age eras.)

If we were to divide the Radium Age into quarters, 1926 would be the final year of its third quarter (1918-1926). How might we characterize this sub-era? Something for me to think about.

Mike Ashley claims that 1926 kicks off phase 1 of a 25-year pulp magazine era.

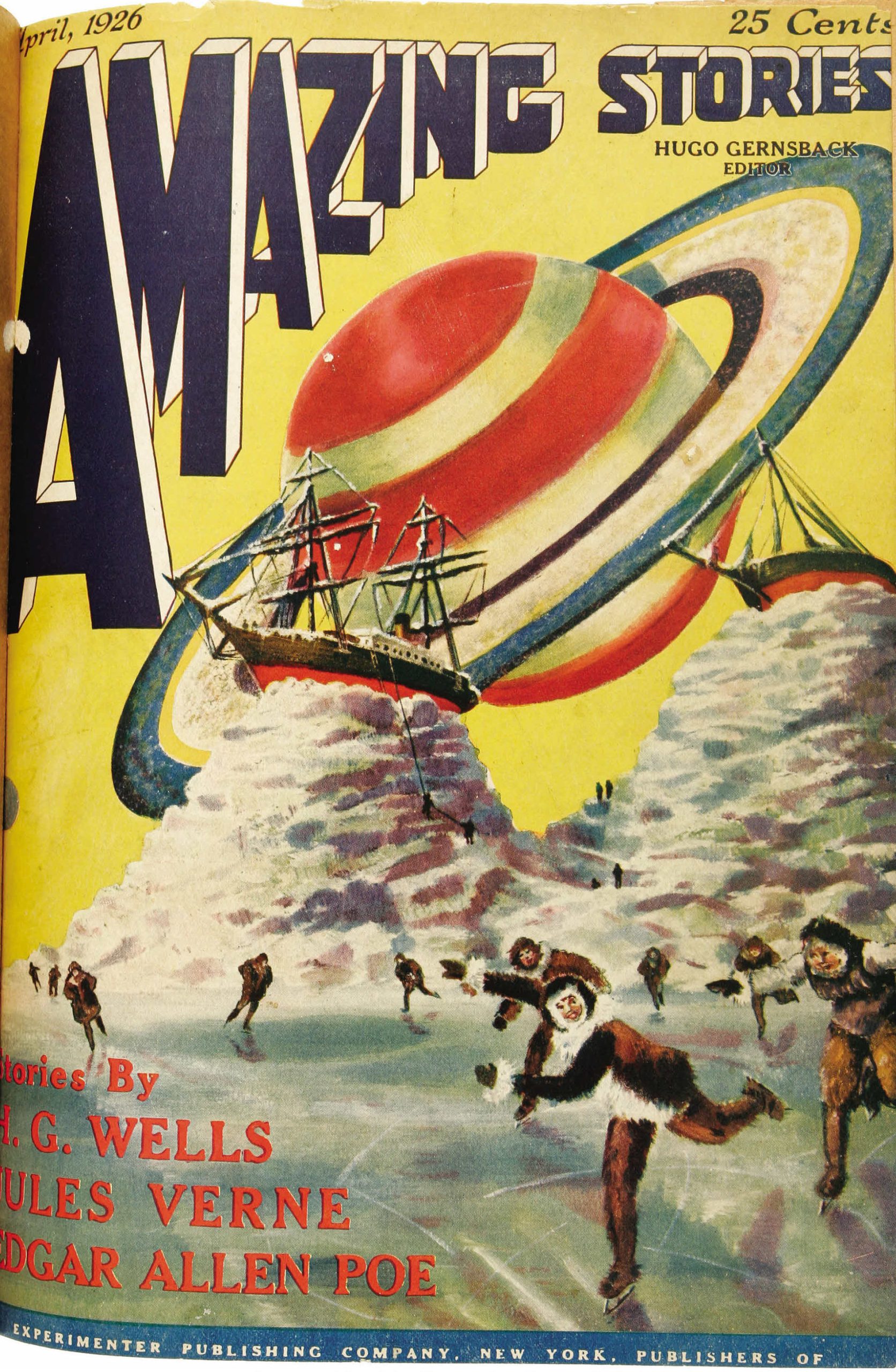

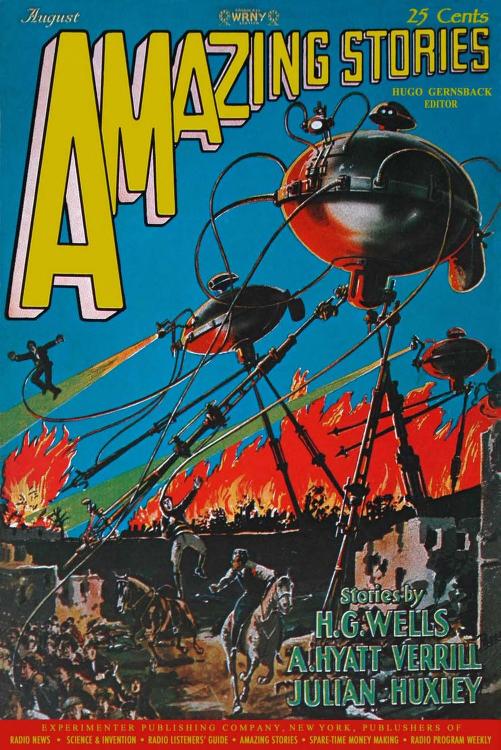

For decades, as we’ve seen in this timeline series, tales of scientific gadgetry and romance had been filling periodical pages in England, France, and America. In March/April 1926, Hugo Gernsback, a Luxembourgian-American inventor and electrical enthusiast, published the inaugural issue of Amazing Stories, the first (and longest-running) English-language magazine dedicated to what was then not quite yet called “science fiction.” Amazing Stories — along with Astounding Stories of Super-Science (later changed to Astounding Science Fiction) and Fantastic Adventures — were to be the three major sf pulps of the 1930s. Gernsback’s magazine would soon enough give a name to fiction treating the speculative and the otherworldly through the lens of systematic realism: “scientifiction.” As importantly, it established a forum for fans of the genre to debate and influence the future of its development. For these reasons, many sf scholars date the “invention” of modern science fiction to 1926.

In the foreword to Amazing’s first number, Gernsback introduced his “New Sort of Magazine,” geared as he said to the “entirely new world” of the modern. He cited as his forebears Poe, Verne, and Wells — and delineated a literary form aiming to instruct as well as entertain, to “impart knowledge … without once making us aware that we are being taught.” In fact, Gernsback was less influenced by scientific romance than by the “scientifiction” (such as his own Ralph 124C41+) that he’d already published in his other magazines. Gernsback’s project involved developing a blueprint for the capitalist technocracies of the future, to be led by daring inventors such as his own Ralph. Gernsback’s magazine — with eye-popping cover illustrations by Frank R. Paul — drew an extensive community of readers, many of whom became sf writers themselves.

Gernsback also introduced a letter column, and encouraged his readers to join in lively discussions there. In the view of Mike Ashley, a historian of science fiction, this was “the real secret of the success of Amazing Stories and is the cause of the popularity of science fiction”: the letter column gave science-fiction fans, many of whom were lonely, a forum in which to make friends and talk about their interests. The resulting community of like-minded readers gave birth to science-fiction fandom, and also to a generation of writers who had grown up reading the genre. In this communal relationship, sf historians tells us, are the roots of SF’s subsequent insularity and ghettoization, as well as the first glimmerings of the genre’s so-called Golden Age.

The first issue of Amazing consisted entirely of reprinted material, including Jules Verne’s novel Off on a Comet, and stories by H.G. Wells and Edgar Allan Poe, but new fiction quickly appeared, with Clare Winger Harris and A. Hyatt Verrill each finding success in one of Gernsback’s early reader competitions.

Amazing was very successful, reaching a circulation of 100,000 in less than a year.

PS: Strictly speaking, due to its large flat format and heavy-duty paper the early issues of Amazing Stories are not really “pulps.”

I have a half-formed thought about the pulps, inspired by the fact that they were so protean — their titles would change, they’d spin off new titles and then reabsorb them, etc. One thinks of engineers putting things out in beta, and letting the user help make final decisions. Which at least in the case of Hugo Gernsback, the tinkerer and inventor, makes perfect sense.

Copyrighted works from 1926 entered US public domain on January 1, 2022. They are now free for all to copy, share, and build upon.

A note on female proto-sf writers in the pulp magazines…

Susanne F. Bozwell’s 2021 essay “‘Whatever it is that compels her to write so seldom’: Network Analysis and the Decline of Women Writers in Pulp Science Fiction” (in Extrapolation) demonstrates that during the 1926–1946 pulp magazine period, women sf writers were “published in ways that made it nearly impossible to gain economic stability and prestige in the pulps.” Although the number of people contributing sf to the pulps increased dramatically, the percentage of them who were female dropped. There were initially many more women authors in sf pulps, but publishers and magazines eventually (and particularly after 1939, when Campbell took over Astounding and transformed it from what he regarded as an impure, generically compromised clearinghouse into what he regarded as a scientifically sound enclave) excluded women from the field — in the name of genre purity. Pointing to archival research by Justine Larbalestier, Bozwell suggests that misogyny towards women in sf became most transparent c. 1938 — the apex of the cultural era that we at HILOBROW call the Thirties (1934–1943). Here we find men writing letters to sf pulps describing these magazines as “free-from-women’s stories,” and no place for “the age-old love idea.” A young Asimov suggests, in one such letter, that pulp magazines that feature impure sf (i.e., featuring romance) alienate readers who are “far superior in intelligence, in emotional maturity and in sensibility.” Asimov, a serial harrasser of women, would go on to make similar claims in his 1970s-era Before the Golden Age anthologies.

Although Bozwell does not distinguish between the sf genre’s Radium Age (c. 1900–1935) and Golden Age (c. 1935–1965), it’s clear that during the Radium Age the pulps were more hospitable to women writers; during the Golden Age, “editorial changes in the name of genre purity led to a steep decline in the publication of women in sf magazines.” Bozwell notes that in the early pulp period (1926–1931), fifty-two women wrote for the pulps. From 1932–1939, as sf’s Radium Age gave way to its Golden Age, the number decreased sharply. As I’ve noted many times, Radium Age proto-sf isn’t a “pure” genre; it’s cobbled together from other genres, including fantasy, romance, adventure, horror, the occult, etc., where women authors were welcome. However, as the Radium Age gave way to the Golden Age, the more sf separated itself from other genres, the more it excluded female authors from its ranks.

As more and more amateur writers turned into professional sf writers, fewer and fewer of them were women. This isn’t to say that women were banned — but most sf pulps published only one or two female authors with any regularity. Astounding had C.L. Moore, Wonder had Leslie Stone, Amazing had Clare Winger Harris, L. Taylor Hansen, and Leslie Stone. Only Weird Tales, which was not strictly an sf magazine, had 10 or more regular female contributors. Gernsback himself may not have been ultra-enlightened, but it’s worth noting that after he sold Wonder Stories in 1936, the number of women’s bylines dropped precipitously.

Proto-sf coinages dating to 1926, according to the Historical Dictionary of Science Fiction: GRAVITY SCREEN (a device that creates or prevents the effects of gravity; the effect of such a device) | INHUMAN (a nonhuman being; cf. alien) | STARSHIP (a spaceship capable of interstellar travel) | VACUUM SUIT (space suit).

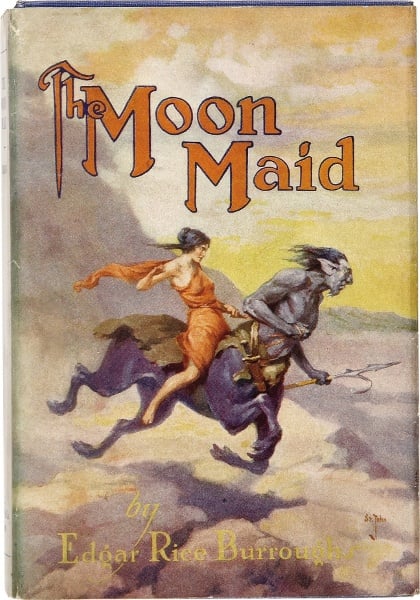

- Edgar Rice Burroughs’s The Moon Maid (1926; collects several stories from earlier years). A sprawling saga that gallops from Julian 5th’s crash-landing on the moon, where he makes a daring getaway (with a moon maid in tow) from subhuman Kalkars who dwell in the asteroid’s hollow interior; to the same Julian’s doomed effort to defeat a Kalkar invasion of Earth; to Julian 9th’s failed but inspiring rebellion against the mongrel descendants of the Moon Men, communistic tyrants who’ve presided over the Earthlings’ regression to a medieval agrarian lifestyle (a proto-Red Dawn vibe if you like that sort of thing); to the final triumph of Red Hawk (Julian 20th), the leader of a primitive tribe of freedom-fighters — who, 400 years after the invasion, defeats humankind’s overlords in a pitched battle set in the ruins of Los Angeles. Fun fact: The Julian 9th story, one hears, was originally written after the Bolshevik revolution, and was rejiggered later to fit into the Moon Maid saga.

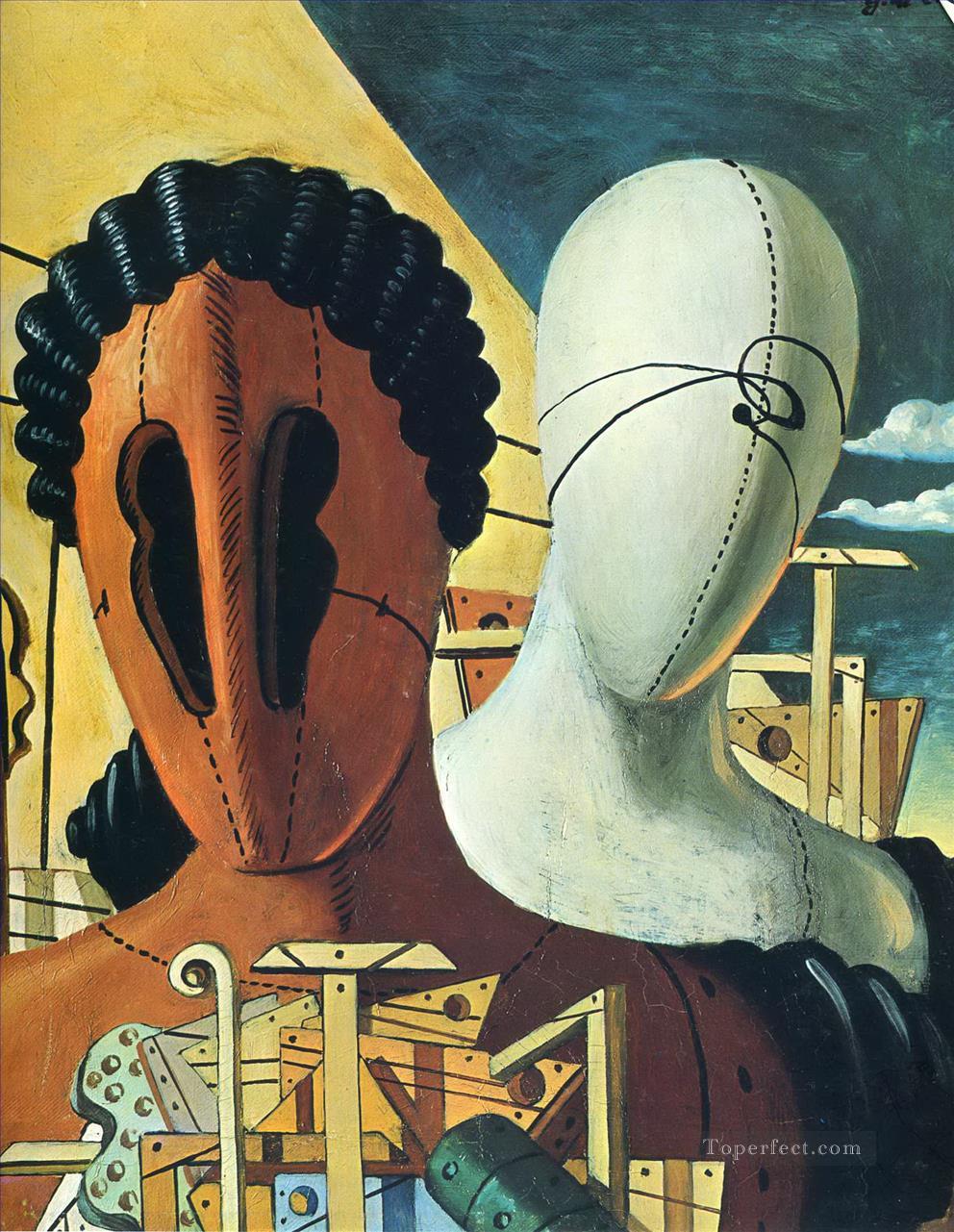

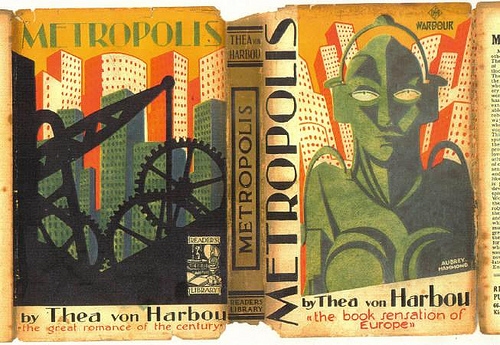

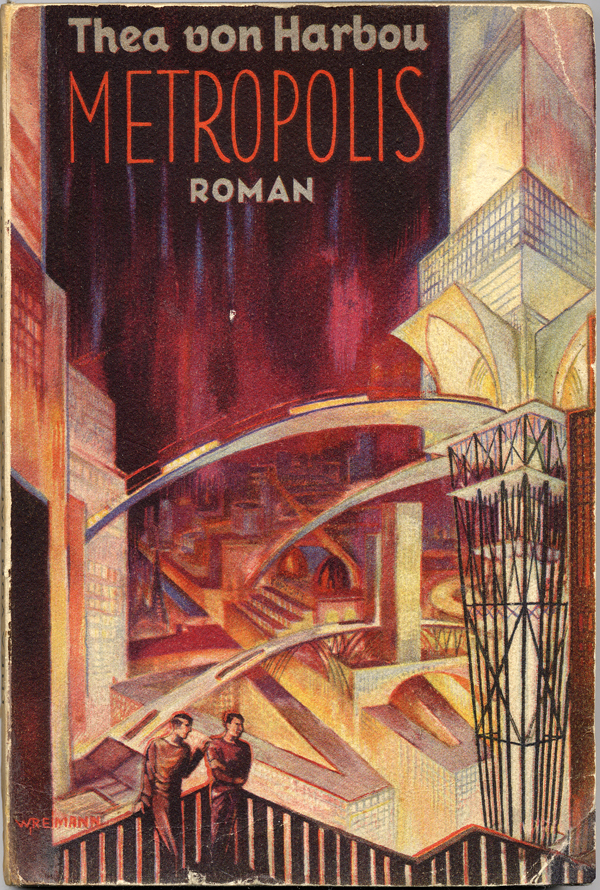

- Thea von Harbou’s Metropolis (1926). Set in a dystopian city-state, this Expressionist novel asks us to imagine a perverse synthesis of Henry Adams’s dynamo-vs.-virgin dichotomy. Metropolis’s Pharaonic master, Joh Fredersen, deplores those weaknesses that make his dehumanized laborers (who wear standard uniforms, and answer to numbers instead of names) inferior to machines. When he orders the mad inventor-magician, Rotwang, to build him “machine men,” Rotwang instead constructs an alluring female-shaped machine whom he names Parody, or Futura: “The being was, indubitably, a woman… But, although it was a woman, it was not human. The body seemed as though made of crystal, through which the bones shone silver.” After rendering Futura’s face in the exact likeness of Maria, a flesh-and-blood woman who is both the conscience of the rebellious workers and the object of Fredersen’s son’s affection, the villainous technocrats program their synthetic Virgin/Dynamo to act as an agent provocateuse. The workers revolt, and Futura/Maria is destroyed. In the end, the Virgin (sentimental religiosity) triumphs over the Dynamo (technology-driven development). Hooray? Fun fact: Von Harbou and her husband, film director Fritz Lang, developed the scenario for Metropolis, then she wrote the novelization while he directed the 1927 movie.

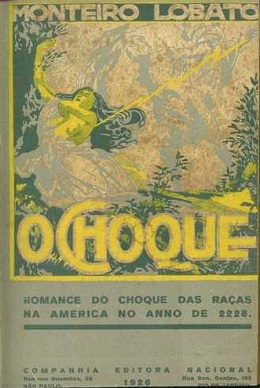

- Monteiro Lobato’s The Negro President (1926). In the year 2228, the USA’s President Kerlog (a white male) faces an unprecedented situation: In his race for reelection, he faces Evelyn Astor (a white feminist) and James Roy Wilde (a black man). Like the actual first black president of the US, Wilde is a cultivated and brilliant man, and a community organizer of sorts. Unlike Barack Obama, Wilde isn’t mixed-race — because race-mixing has been outlawed in America; the novel’s author, I’m sorry to report, appears to be in favor of this eugenicist policy. Although Kerlog offers an alliance with Roy — black votes in exchange for easing the Race Code setting limits on the growth of the black population — Roy wins the election. Kerlog then enlists Astor in an effort to protect the interests of the white race… and Roy is found dead on the day that he was supposed to assume office. Fun fact: Lobato was one of Brazil’s most influential writers, mostly because of his children’s books set on the fictional Yellow Woodpecker Farm.

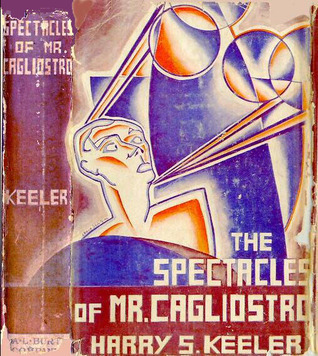

- Harry Stephen Keeler’s The Spectacles of Mr. Cagliostro (vt The Blue Spectacles, 1931). These allow the reading of a secret message that is blazoned across the country on billboards. (It’s the paranoid tale of a man who can’t get anyone to believe he’s the heir to his uncle’s fortune. Not only that, in order to inherit, he has to wear these heavy blue spectacles for a year.) Is this where Carpenter’s They Live comes from?

- Archibald Macleish’s poem “Einstein.” In the 1926 collection Streets in the Moon (the title of which is sf-ish). Published as a stand-alone book in 1929. Presents a day’s meditation that recapitulates the major stages in Einstein’s physical and metaphysical struggle to contain and comprehend the physical universe, from classical empiricism through romantic empathy to modern, introspective, analytic physics.

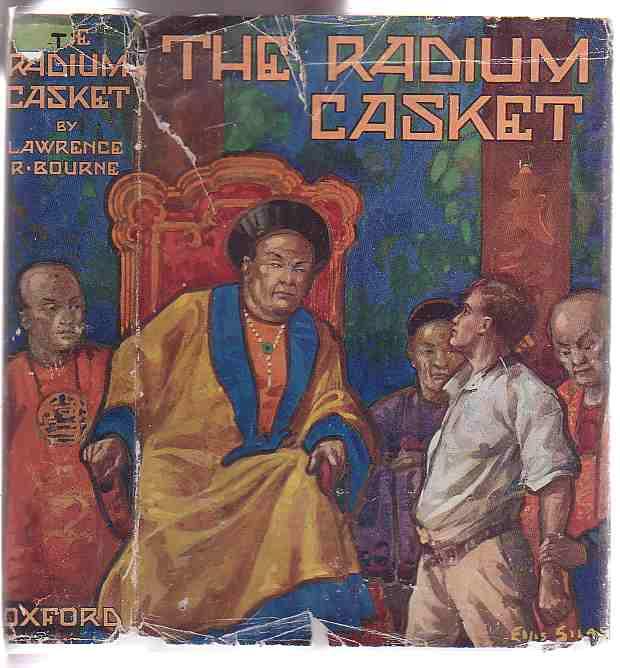

- Lawrence Bourne’s The Radium Casket. A story of China and the South Seas. There’s a sequel titled Radium Island. Not sure if these are sf?

- Greye La Spina (Fanny Greye Bragg)’s “Fettered.” La Spina (1880 – 1969) was an American writer who published more than one hundred short stories, serials, novelettes, and one-act plays. Mostly supernatural stuff. She is probably best known for Invaders from the Dark (1925), an old-fashioned but entertaining werewolf story. This one is a vampire story — is there an sf element?

- Guy Dent’s Emperor of the If. The scientist Greyne believes that the universe is maintained by the power of thought and that thought surges through every particle of matter; finally, he succeeds in gaining control of this force. Using a greengrocer’s brain-in-a-jar, he ventures out in the “world of if” — one in which the glacial period has never happened. Chaos reigns — except in one half-mile circle maintained by the will of an elderly woman who recognizes Greyne’s experiment for what it is and declares it evil. (I’m reminded, sort of, of John Christopher’s Weathermonger series.) In a second experiment, Greyne and his comrades want to see what will happen to the world if its present undesirable trends continue unchecked — two million years in the future. The earth no longer rotates, and the handful of human inhabitants are merely slaves of the machines that have become the dominant life forms — sort of like Iain M. Banks’s artificial intelligences, but not so benevolent. “An excellent idea, but muddled by weak literary skill and careless editing. Inconsistencies, loose ends, and lack of development hinder the story, while thereligious sops are unnecessary and very annoying.” — Bleiler.

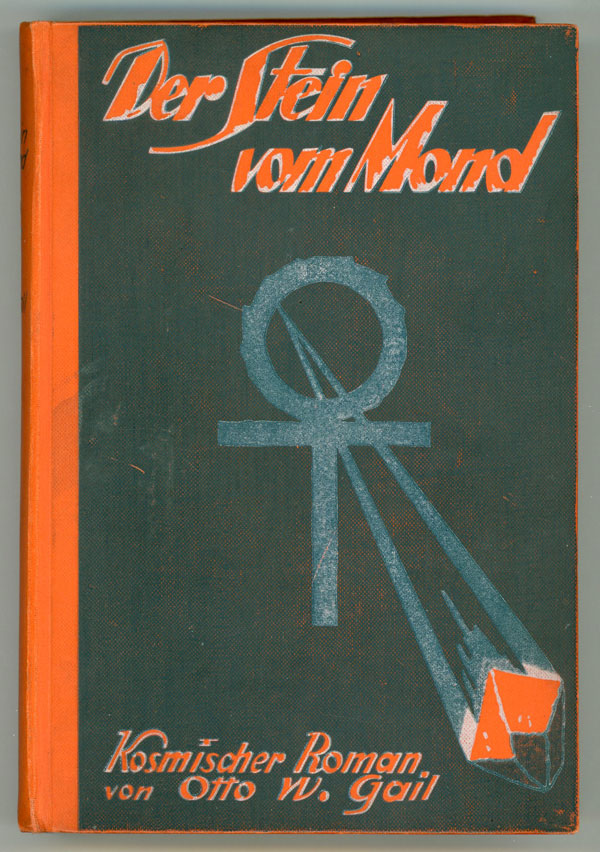

- Otto Willi Gail’s Der Stein vom Mond. Sequel to DER SCHUSS INS ALL (1925). A novel set in the near future that takes place in the Atlantic ocean, on the Yucatan Peninsula and in space near Venus. The parts of the novel concerning Yucatan and Atlantis have an occult tone and some crank science is involved. The interplanetary portion is more sound and practical. “… combines elements from Blavataksy’s Theosophy with contemporary rocketry.” – Bleiler

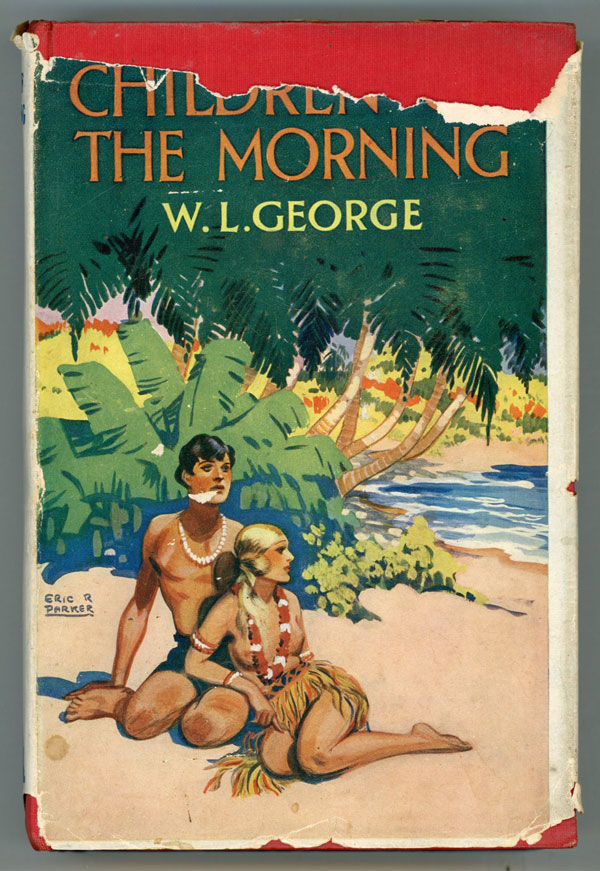

- W.L. George’s Children of the Morning. Not exactly sf — though utopian, perhaps. The author’s posthumous last novel, a story about a group of children growing up without adults on a deserted island, and their discovery of sex, violence, superstition and agriculture. “The story contrasts sharply with the romantic Robinsonades so fashionable in the nineteenth century, and provides a remarkable anticipation of William Golding’s Lord of the Flies.” – Stableford, Scientific Romance in Britain, 1890-1950.

- Diane Boswell’s Posterity. See this list of Pre-1950 Utopias and Science Fiction by Women.

- I. F.Grant’s A Candle in the Hills. See this list of Pre-1950 Utopias and Science Fiction by Women.

- Reginald Glossop’s The Orphan of Space. A cautionary future war novel, a mix of hard-core science fiction and mysticism, that depicts the “terrible results of the Yellow Peril combined with Bolshevism.” Ultimately, the allies destroy Moscow, the enemy’s seat of power, with an atomic bomb. “A fantastic tale of a future period when a wicked dictator is favoured by Satan.” – Clarke, Tale of the Future . “The sort of novel M.P. Shiel might have written had he forgotten how to write… imaginative, but amateurish and slightly eccentric.” – Bleiler. “…lamely prefigures C. S. Lewis’s RANSOM trilogy in the conceit that Earth is a diseased planet barred from the higher spheres. The plot concerns the collaboration of a kind of spirit of Gaia with the ghost of a long-dead Chinese scientist to pass the secret of atomic energy on to the protagonists in 1935, so they can cleanse the planet of its ailment.” – Clute and Nicholls.

- C.E. Jacomb’s And a New Earth. A millionaire has established on Easter Island an elitist eugenics-based society, which is forced to defend itself against the major powers and the Church, employing the advanced weaponry it has developed; during the course of this conflict civilization in general is wiped out by a great flood in 1958; but the island survives, and culture develops slowly anew, though the elite community does not itself flourish indefinitely. “Post-catastrophe, second flood. ‘Civilization’ discovers remnant of small island where a utopian society had been established prior to the catastrophe and had survived, isolated from the rest of the world.” – Lewis, Utopian Literature. “Elitist social theories and geographical upheavals… An obvious source for Olaf Stapledon’s Odd John.” – Bleiler.

- F.H. Ridley’s The Green Machine. Mr. Jinks journeys via a comet to Mars which is inhabited by numerous monstrous creatures and a highly civilized race of human-sized ants. “An odd novel, obviously written by an intelligent man who had very little scientific background. It is original in idea, yet amateurish in presentation, at times edging into eccentricity … A highly individual book in some ways, with a fairy tale approach, despite echoes of H. G. Wells, E. R. Burroughs, Verne, and the American pulps, but annoying in its bland approach to matters scientific. The author lacks the literary skills to make the horrors of Mars come alive, but it is to his credit that he did not fall back on Dejah Thoris.” – Bleiler

- R.W. Service’s The Master of the Microbe. Science fiction thriller of search for deadly bacillus stolen by criminal mastermind.

- Robert M. Coates’s The Eater of Darkness. The author’s first book, “an ignored minor masterpiece of antirealistic fiction, a novel that deserves the attention of all students of fantasy literature.” – Survey of Modern Fantasy Literature I. Coates’ novel “quite brilliantly applies a wide arsenal of literary devices, some of them surrealistic, to the exaggeratedly spoof-like tale of a master criminal and his absurd super-weapon, which sees through solids and applies remote-control heat to kill people invisibly; beneath the spoofing and the cosmopolitan style lies a sense of horror.” – Clute and Nicholls (eds), The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction.

- C.S. Lewis’s poem Dymer is of sf interest. He worked on this as early as 1916 — at the age of 17. Published pseudonymously in 1926. Dymer follows the adventures of its titular protagonist from his birth in a totalitarian state, mockingly referred to as “The Perfect City.” After leaving the city, he discovers that a revolutionary named Bran used Dymer’s actions and name to instill violent protest in the citizens, who then went on to sack and raze the city. In the end, he dons armor and prepares to fight a horrible monster… his own offspring. Idiosyncratic and problematic, Dymer nevertheless makes for provocative reading, with a philosophical vision that is striking if not precisely clear. Fun facts: David Downing calls it “obscure and artistically undistinguished.” Chad Walsh calls it a failure as a whole, while A.N. Wilson suggests that only the most dedicated Lewis enthusiasts “can ever have bothered to press on with Dymer.”

- Noëlle Roger’s The New Adam. See this list of Pre-1950 Utopias and Science Fiction by Women.

- Gladys St. John-Loe’s The Door of Beyond. See this list of Pre-1950 Utopias and Science Fiction by Women.

- Dorothy Mills’s Phoenix. About a woman who undergoes a rejuvenation process. Jim Harris maintains a website about her. UK author of several travel books which record her adventurous life in Africa and South America, and of three books of sf interest: The Arms of the Sun (1924), a Lost World tale set in Africa, where a white woman is worshipped by “natives”; The Dark Gods (1925), also set in an indefinably mysterious Africa; and Phoenix (1926), in which a foreigner (a mad scientist who cannot control his sexual urges) subjects an elderly woman to his invention, a rejuvenation treatment which makes her young. Fun fact: Lady Dorothy Mills is believed to be the first “white woman” to visit Timbuktu.

- Mikhail Kozyrev’s dystopian novel Leningrad. See Drozdz’s essay on “Parodies of Authority in the Soviet Anti-Utopias from 1918-1930.” The twentieth century witnessed the first incarnation of utopian dreams in Russia, and, as a byproduct, the vitality of the literary anti-utopia. One of the first powerful critiques of totalitar-ianism, Zamiatin’s We (see 1920), was followed by Kozyrev’s Leningrad (1925), and Andrei Platonov’s Chevengur (1926-29) and The Foundation Pit.

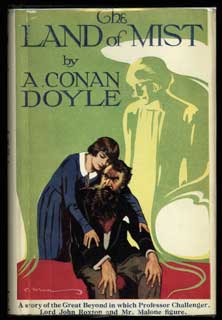

- Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Land of Mist. The third and final Professor Challenger novel. In which the scientist investigates and is converted to spiritualism. Long and mostly tedious.

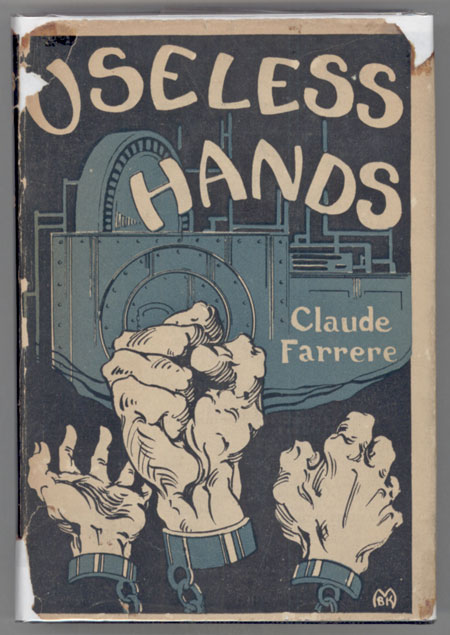

- Claude Farrere (pseudonym of Frederic Charles Pierre Edouard Bargon)’s Useless Hands. Translation of Les Condamnés a Mort — see 1920.

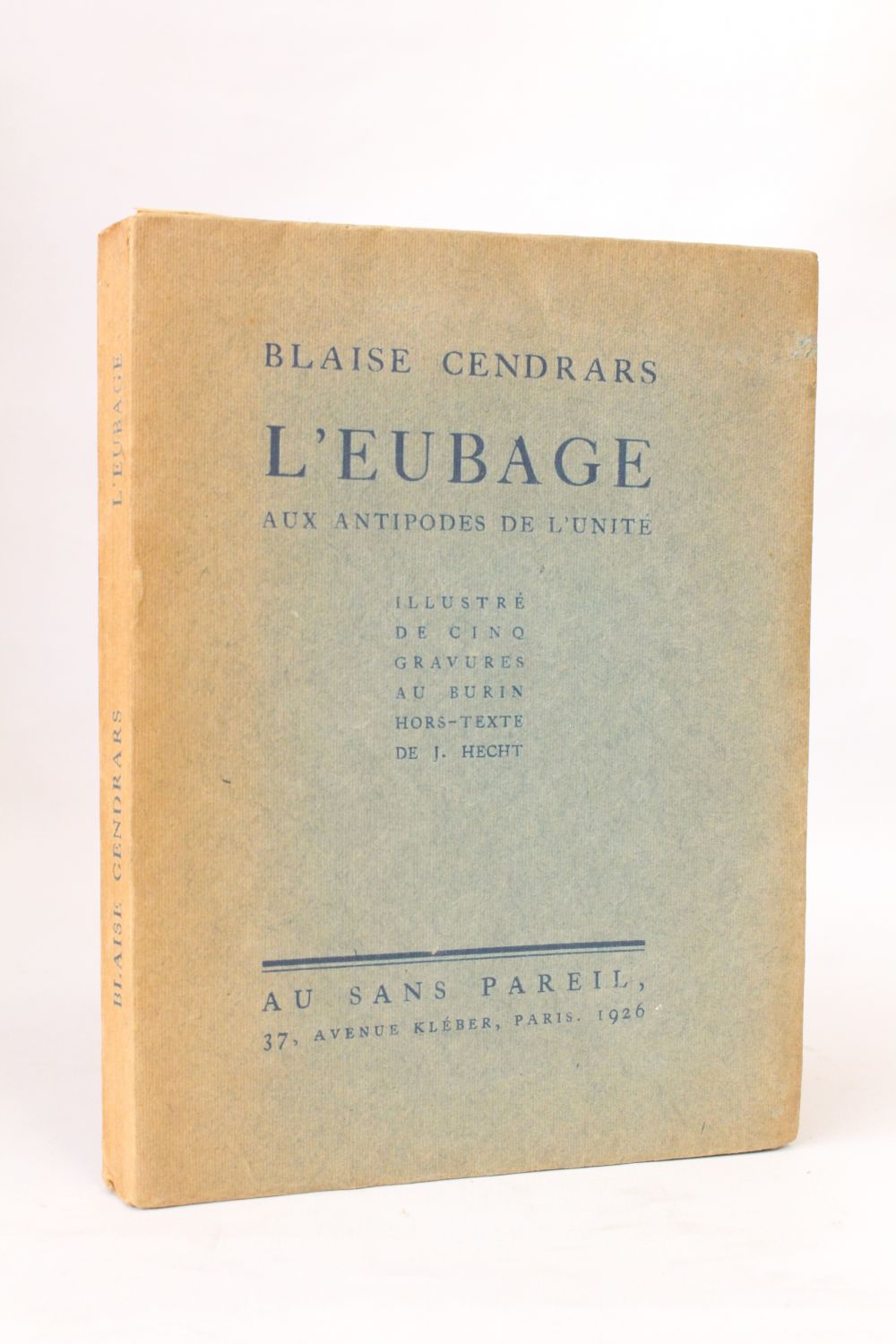

- Blaise Cendrars’s L’Eubage, aux antipodes de l’unité (trans. Esther Allen as The Eubage; Or, at the Antipodes of Unity). Combines interstellar space opera and deadpan philosophical musings, anticipatory of Lem’s sf. Surreal without social or political implications. A work of great lyrical beauty. What is an eubage? A French priest who practices fortune-telling and astrology. On this voyage science is put to use for the discovery of the forces and forms of life and of the spirit; we approach a religious endeavour. The book was conceived with numerous illustrations, all of mechanical or scientific apparatuses and descriptions of their functions. (Cendrars’ production attempts to transform science and machinery into something more human, or to find something essentially human in the machine’s movements.) Fun fact: Cendrars is the pseudonym of Swiss-born editor, controversialist, adventurer (though his memoirs contain a great deal of fiction), poet, film maker and author Frédéric-Louis Sauser (1887-1961). See 1919 for Cendrars’ Le fin du monde filmée par l’Ange Notre-Dame, and 1924 for his Kodak.

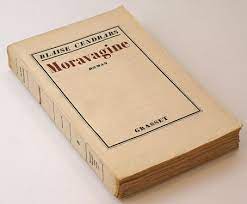

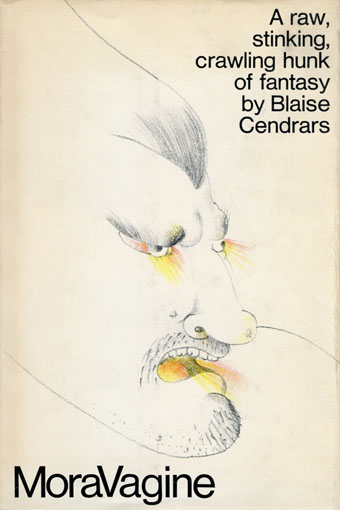

- Blaise Cendrars’s Moravagine (translated Alan Brown 1969). Scabrous, amoral, misogynist, misanthropic. A picaresque narrated by a young doctor who frees the mysterious Moravagine — a serial killer — from an asylum where he’s been imprisoned for many years. (John Coulthart notes: “’Moravagine’ is an adopted name whose origin and meaning is never addressed, although a French reader would find a rather unavoidable pun on ‘death by vagina.'”) Moravagine himself is an otherwise unnamed member of the Hungarian royal family, a dwarfish intellectual psychopath with a bad leg who goes on the run with the doctor, first to pre-revolutionary Russia, then to the United States and South America. Cendrars appears as a character in the later chapters. Why is this book of proto-sf interest? The SFE suggests that the narrator is something of a mad scientist type.

- Booth Tarkington’s “The Veiled Feminists of Atlantis.” Written not long after the 19th Amendment guaranteed American women the right to vote, Tarkington’s story reimagines the legend of Atlantis’s demise as a satire of the war between the sexes. Having agitated for the opportunity to learn the menfolk’s “magic”—technology sufficiently advanced to be indistinguishable from magic — the women of Atlantis achieve not only social, economic, and political equality but predominance… at which point they re-adopt the veils which, during their campaign for equality, they’d cast off. Outraged at their own loss of status and power, the men revolt. Will be reissued by MIT Press as part of the collection More Voices from the Radium Age.

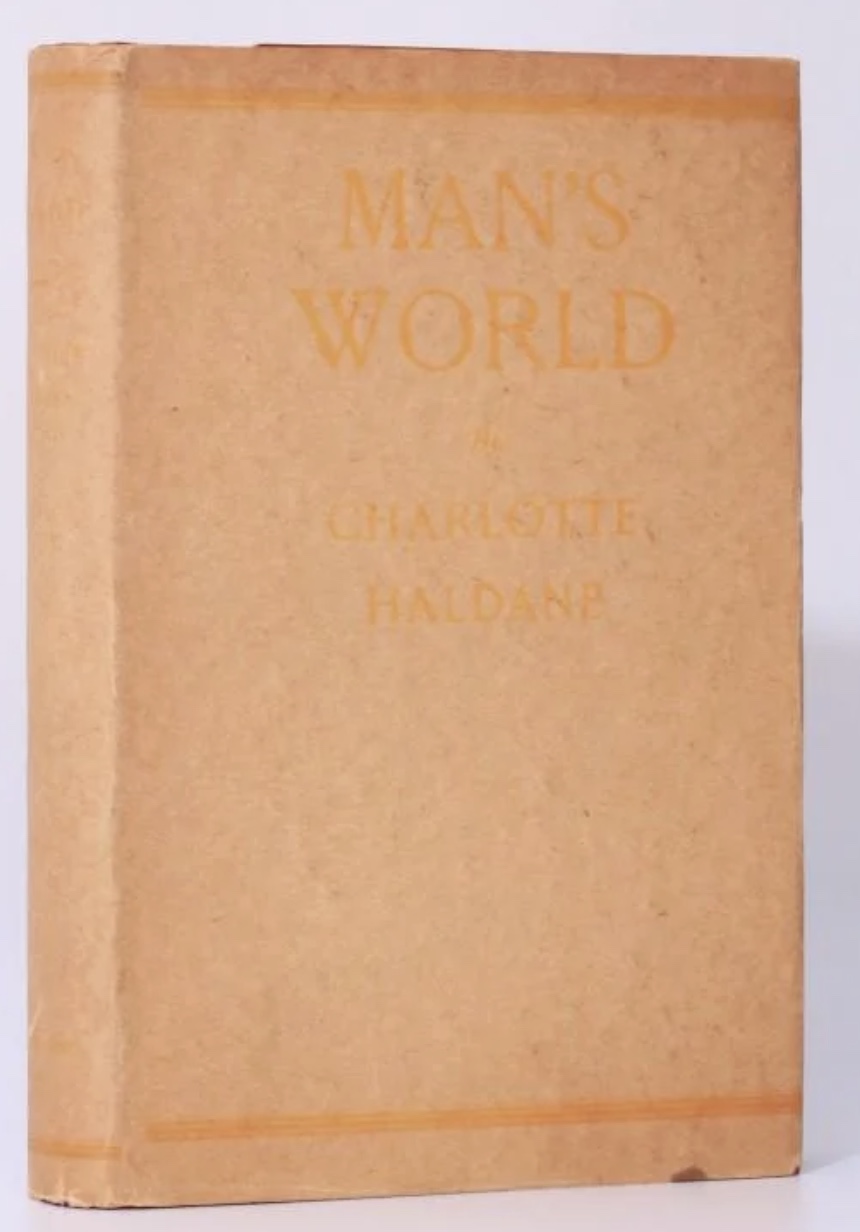

- Charlotte Haldane’s Man’s World. A HILOBROW reader got in touch, some time ago, to tell me: “You are missing one very key text, Man’s World (1926) by Charlotte Haldane, the wife of the biologist J.B.S. Haldane and sister-in-law of Naomi Mitchison. More so than Rose Macaulay’s What Not, it’s the novel that most strongly anticipates Huxley and Orwell.” With the help of my friend Matthew Battles, I tracked down a copy of this rare book. Indeed: In the not-too-distant future, eugenics has triumphed. From adolescence women are groomed to be “vocational mothers” or else, if they have no interest in motherhood, they are sterilized by the government and become “neuters.” Haldane’s ambivalent story, which draws not only on the arguments of her scientist husband J.B.S. Haldane, who espoused eugenics and predicted genetic engineering, but also on Bertrand Russell’s spirited riposte to J.B.S.’s theories, introduces us to Nicolette, a young woman who rebels against her conditioning, and to her brother Christopher, who — like Huxley’s “Savage” will in Brave New World — decides that utopia is… dystopian.

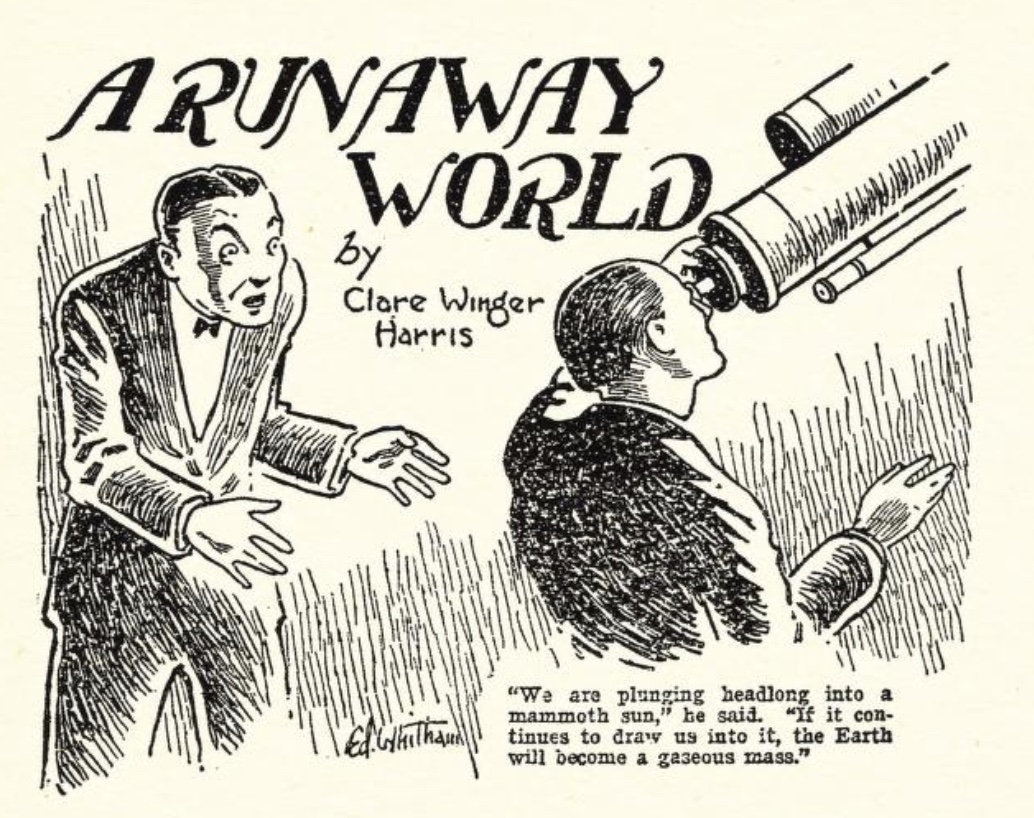

- Clare Winger Harris’s “A Runaway World” (Weird Tales, July 1926). Just as we are monkeying with subatomic particles, our own solar system is being monkeyed with! A century in the future, Mars is suddenly pulled from its orbit. Not long later, Earth follows suit and the catastrophe is accompanied by rioting. Although three years pass with the planet far away from the sun, the Griffins and their colleagues are able to survive on the food they managed to stockpile and through the use of their atomic heater. Harris plays around with the idea that the planets can move between stars, much as high level electrons can move between nuclei of atoms. There is little tension or conflict in the story, which is more a description of events, something which will be repeated throughout Harris’s work. Fun facts: Clare Winger Harris is credited as being the first woman to write science fiction for an American magazine under her own name. This is her first published story. In all, Clare Winger Harris wrote eleven stories published in Weird Tales, Amazing Stories, and Science Wonder Quarterly from 1926 to 1930.

- Hemendrakumar Roy’s Maynamatir Mayakanan (The Enchanted Garden of Maynamati). A Lost World adventure. More info on this Bangla-language novel to come.

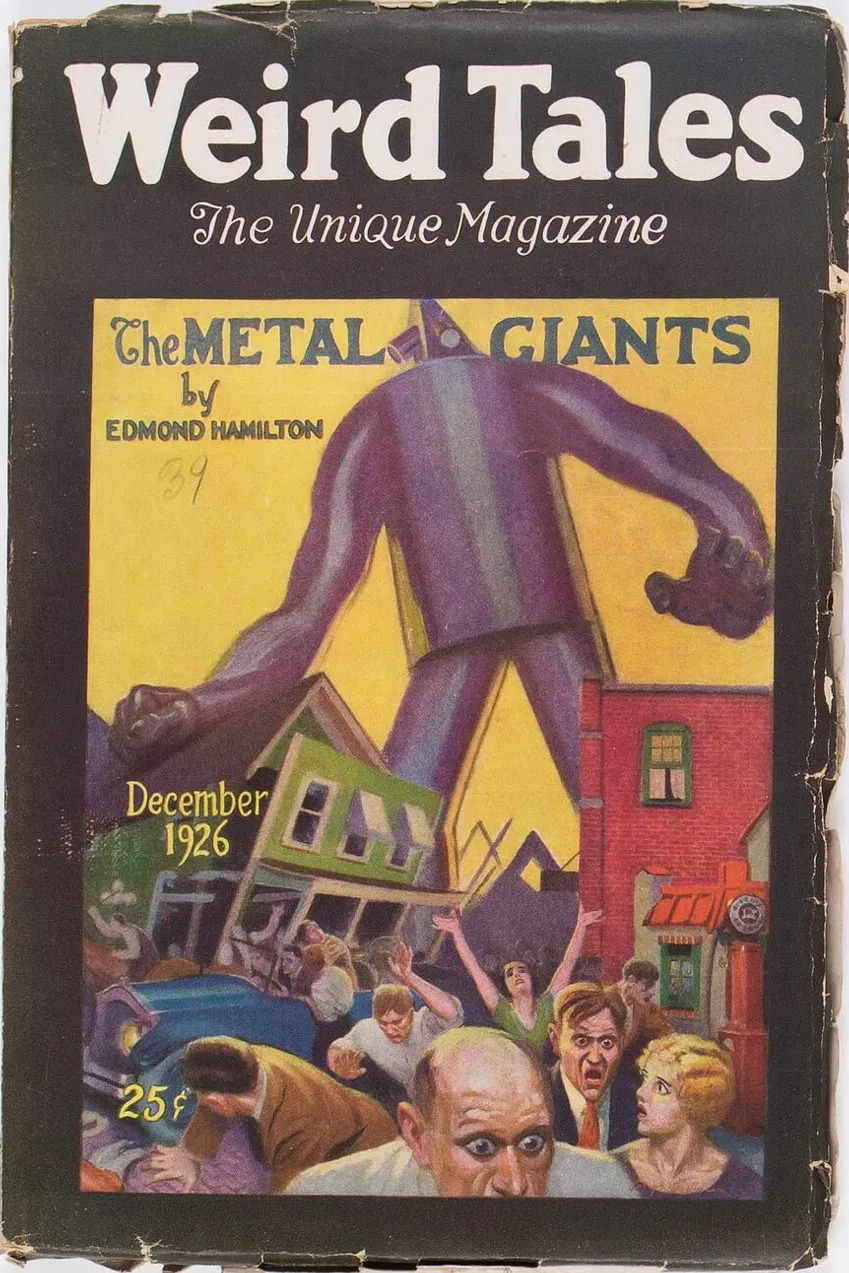

- Edmond Hamilton’s “The Metal Giants.” First appeared in the December 1926 Weird Tales. Notable for theorizing an artificial brain. “Detmold had attacked the problem from a different standpoint. It was his theory that the sensations of the nervous system are flashed to the brain as electric currents, or vibrations, and that it was the action of these vibratory currents on the brain-stuff that caused consciousness and thought. Thus, instead of trying to make simple, living cells and from them work up the complicated structure of the brain, he had constructed an organ, a brain, of metal, entirely inorganic and lifeless, yet whose atomic structure he claimed was analogous to the atomic structure of a living brain. He had then applied countless different electrical vibrations to this metallic brain-stuff, and finally announced that under vibrations of certain frequencies the organ had showed faint signs of consciousness.”

- Damir Feigel’s proto-sf adventure novel Pasja dlaka! (Hair of the Dog!). Yugoslavian. Also author of Na skrivnostnih tleh (On the Mysterious Ground, 1929), Čudežno oko (The Miraculous Eye, 1930), and Okoli sveta/8 (Around the World/8, 1935).

- Edmond Hamilton’s “The Monster-God of Mamurth.” His first story? For Weird Tales in August 1926. Vulgarized the florid weird-science world of Abraham Merritt, only hinted at the exploits to come, though Hamilton found Science Fantasy a fertile vein. This story and others were collected in his first book, The Horror on the Asteroid & Other Tales of Planetary Horror (1936).

- Edmond Hamilton’s “Across Space” (September-November 1926 Weird Tales). About refugees from Mars who have hidden for centuries on Easter Island. Bat-like Martians who have a race of synthetic android servants. Their dread purpose is to bring Earth close to Mars so the Martian race can take over the planet. Ashley notes that Hamilton is the writer most associated with the development of space opera. This is the first story he sold, though “Monster God of Mamutth” was printed first.

- Enéas Lintz’s Há dez mil séculos [“Ten Thousand Centuries Ago”]. The author is Brazilian. Aa traveller in the mountains meets an old man who by means of telepathy reveals to him some fundamental secrets of the universe, including the interior of the atom, besides taking him on a mental journey through the solar system. All very proto-Castaneda, sounds like.

- Julian Huxley’s “The Tissue-Culture King” (1926 in Cornhill Magazine and in The Yale Review, reprinted 1927 in Amazing Stories and many times afterwards). The story tells of a biologist captured by an African tribe. It incorporates the idea of immortality based on reproduction from a tissue culture and genetic engineering, and an early mention of tin foil hats and their supposed anti-telepathic properties. Brother of Aldous Huxley, Julian was an English evolutionary biologist, eugenicist, and internationalist. Serialized here at HILOBROW during 2022.

- Maurice Renard’s L’invitation à la peur [Invitation to Fear] (story collection). This and his collections Le Carnaval du mystère [The Carnival of Mystery] (1929) and Celui qui n’a pas tué [He Who Did Not Kill] (posthumous) include many fine stories, mostly extremely short, on a great variety of sf themes: clones, invisibility, time travel,cyborgs, gravity, time paradoxes, eschatology and, especially and often, altered modes of perception.

- Muriel Jaeger’s The Question Mark. Her first sf work, it depicts a utopian UK of 200 years hence (as witnessed by the protagonist, who has been roused from a cataleptic trance) and shows strongly the influences of William Morris, Edward Bellamy and H G Wells, though she deliberately undermines their visions by depicting her utopia in terms of the imperfectly dedicated mortals who occupy it, for they are imperfectly dedicated, as the visitor observes, to the rigorous austerities required of Samurai in Wells’s A Modern Utopia (1905). Brian Stableford has suggested that this undercutting of traditional visions of utopia influenced Huxley’s Brave New World (1932).

- Rudyard Kipling’s collection Debits and Credits. A mixed collection consisting of twenty-one poems and fourteen stories, including six which are fantasy or science fiction: “The Enemies to Each Other,” “The Wish House,” “A Madonna of the Trenches,” “On the Gate: A Tale of ’16,” “The Eye of Allah” and “The Gardener.” Perhaps Kipling’s finest collection of short fiction. “The Eye of Allah” implies the Alternate History that is almost generated when a microscope falls into the hands of medieval English churchmen, revealing a world of “demon” animalculae and bacteria.

- Curt Siodmak’s “The Eggs from Lake Tanganyika” (April 1926 Scherl’s Magazin as “Die Eier vom Tanganjikasee”; July 1926 Amazing). Four gigantic, blood-sucking flies get loose in Berlin and must be destroyed at all cost. Fun facts: Though he trained as a railway engineer, Siodmak became a journalist and film reporter, serving as an extra on Metropolis (1926) in order to secure an interview with Fritz Lang. He entered the film industry in 1929 as a screenwriter working sometimes with his elder brother Robert Siodmak, who became a prominent director.

ALSO: Heisenberg further develops the quantum theory; Morgan’s The Theory of the Gene. Fascist youth organizations in Germany and Italy. General strike called in England. Trotsky expelled from Moscow. Hirohito becomes emperor of Japan. Hemingway’s The Sun Also Rises, Kafka’s The Castle (posthumous), Milne’s Winnie the Pooh. Lang’s Metropolis (see Thea von Harbou entry, above); Lubitsch leaves Berlin for Hollywood. Duke Ellington’s first records. Amundsen flied over North Pole in an airship; Goddard fires the first liquid fuel rocket. Death of Harry Houdini.

The founding work of poetry and science, I. A. Richards’s Science and Poetry (1926). Richards is probably reacting to JBS Haldane’s Daedalus; but in addition to expressing concerns about science, his work also treats poetry and science as an object of study in its own right. Science and Poetry is known for its classification of science into ‘statements’ which were verifiable, and poetry into ‘pseudo-statements’ which were not.

In 1913, Neils Bohr, a student of Rutherford’s, developed a new model of the atom. In 1926 Erwin Schrödinger, an Austrian physicist, took the Bohr atom model one step further. Schrödinger used mathematical equations to describe the likelihood of finding an electron in a certain position. This atomic model is known as the quantum mechanical model of the atom.

It wasn’t until physicists had a quantum model of the atom that they were able to understand what was going on with radioactive decay. They found that the atomic nucleus was really a loose, gooey bag of protons and neutrons all sloshing around against each other. That gooey bag had a lot of complicated physics going on inside it.

For one, there’s the strong nuclear force itself, which is responsible for forming triplets of quarks into neutrons and protons. Some of this strong force “leaks out” of the neutrons and protons, however, and it’s that leftover force that is responsible for forming atomic nuclei.

Second, the protons in a nucleus are positively charged, and like-minded charges absolutely loathe being close to each other. The protons are constantly trying to push themselves away from each other, but they are usually kept in check by the gluing ability of the strong nuclear force. Occasionally, the weak nuclear force makes an appearance too, with its ability to transform a proton into a neutron and vice versa.

Most atomic nuclei are stable most of the time; the balance of forces inside them keep them together. But sometimes, things can become unbalanced.

If there are too many protons, for example, the electrostatic repulsion of those protons destabilizes the nucleus. Or, if there are too many neutrons, the strong force isn’t always capable of keeping everything together and preventing neutrons from wandering away.

If an atomic nucleus isn’t in its lowest-energy state possible, radioactive decay can happen when the nucleus reshuffles and reorganizes itself to find a new stable situation. The different ways a nucleus can rearrange itself lead to the different kinds of radiation.

In classical physics, radioactive decay could never happen, because it is not possible to spend energy that does not exist. Quantum mechanics allows for this to happen, but it does so randomly. Every once in a while, a slightly unstable atomic nucleus will spontaneously decay into something else.

Even though we can never know when a single atom will decay, we can build statistics of how a whole population of atoms will decay. That’s the idea behind a half-life.

Unlike the Bohr model, the quantum mechanical model does not define the exact path of an electron, but rather, predicts the odds of the location of the electron. This model can be portrayed as a nucleus surrounded by an electron cloud. Where the cloud is most dense, the probability of finding the electron is greatest, and conversely, the electron is less likely to be in a less dense area of the cloud. Thus, this model introduced the concept of sub-energy levels.

Schrödinger combined the equations for the behavior of waves with the de Broglie equation to generate a mathematical model for the distribution of electrons in an atom. The advantage of this model is that it consists of mathematical equations known as wave functions that satisfy the requirements placed on the behavior of electrons. The disadvantage is that it is difficult to imagine a physical model of electrons as waves.

The Schrödinger model assumes that the electron is a wave and tries to describe the regions in space, or orbitals, where electrons are most likely to be found. Instead of trying to tell us where the electron is at any time, the Schrödinger model describes the probability that an electron can be found in a given region of space at a given time. This model no longer tells us where the electron is; it only tells us where it might be.

The Bohr model was a one-dimensional model that used one quantum number to describe the distribution of electrons in the atom. The only information that was important was the size of the orbit, which was described by the n quantum number. Schrödinger’s model allowed the electron to occupy three-dimensional space. It therefore required three coordinates, or three quantum numbers, to describe the orbitals in which electrons can be found.

See 1932 for Chadwick’s discovery of the neutron.

Waldo Frank’s 1926 Virgin Spain suggests that the straight line is a symbol of the worldly, acquisitive, act. “The unreligious is the incomplete. And its symbol is the unreal straight line which moves away from its beginning. As mathematics becomes non·Euclidean, it tends toward the religious. In place of the pagan straight line, we have the geodesic· line which meets its source and completes a body for gravitational

and inertial forces.” What Frank means here is that since the geodesic line — and by extension, the circle, is infinite (having no beginning or end) it is a mystical prefiguration of eternity, whereas a straight line (which must have a beginning and an end, if space is curved) is finite and worldly. The circle thus becomes a primary religious symbol.

MORE RADIUM AGE SCI FI ON HILOBROW: HiLoBooks homepage! | What is Radium Age science fiction? |Radium Age 100: 100 Best Science Fiction Novels from 1904–33 | Radium Age Supermen | Radium Age Robots | Radium Age Apocalypses | Radium Age Telepaths | Radium Age Eco-Catastrophes | Radium Age Cover Art (1) | SF’s Best Year Ever: 1912 | Radium Age Science Fiction Poetry | Enter Highbrowism | Bathybius! Primordial ooze in Radium Age sf | War and Peace Games (H.G. Wells’s training manuals for supermen) | Radium Age: Context series | J.D. Beresford | Algernon Blackwood | Edgar Rice Burroughs | Karel Čapek | Buster Crabbe | August Derleth | Arthur Conan Doyle | Hugo Gernsback | Charlotte Perkins Gilman | Cicely Hamilton | Hermann Hesse | William Hope Hodgson | Aldous Huxley | Inez Haynes Irwin | Alfred Jarry | Jack Kirby (Radium Age sf’s influence on) | Murray Leinster | Gustave Le Rouge | Gaston Leroux | David Lindsay | Jack London | H.P. Lovecraft | A. Merritt | Maureen O’Sullivan | Sax Rohmer | Paul Scheerbart | Upton Sinclair | Clark Ashton Smith | E.E. “Doc” Smith | Olaf Stapledon | John Taine | H.G. Wells | Jack Williamson | Stanisław Ignacy Witkiewicz | S. Fowler Wright | Philip Gordon Wylie | Yevgeny Zamyatin