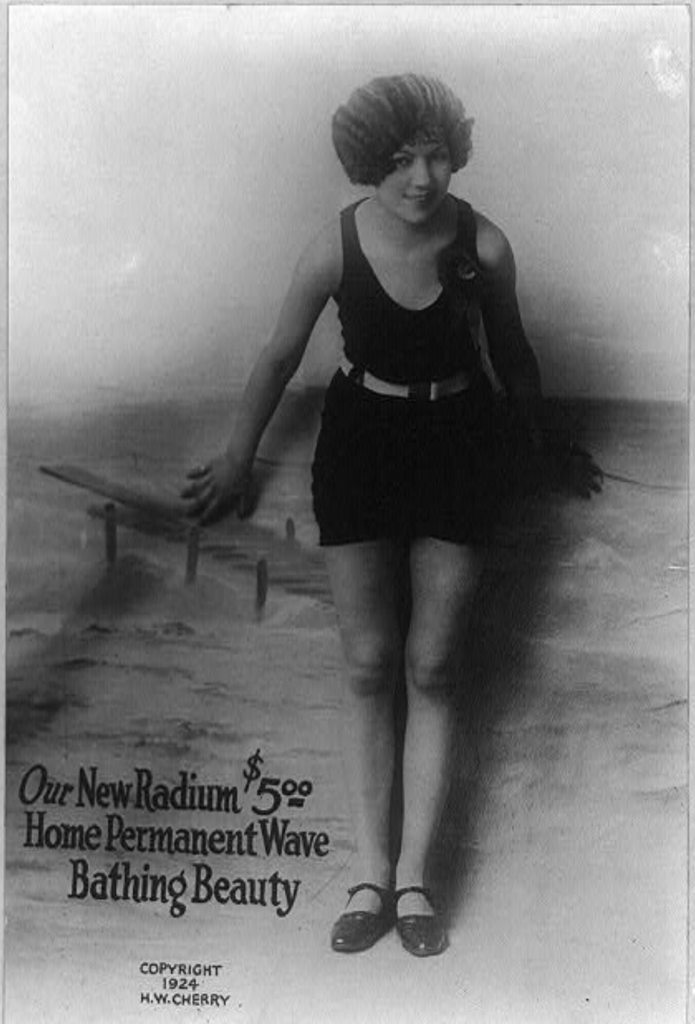

RADIUM AGE: 1924

By:

October 2, 2022

A series of notes — Josh calls it a “timeline,” but Kulturfahrplan might be the more apt term — towards a comprehensive account of the science fiction genre’s Radium Age (1900–1935). These notes are very rough-and-ready, and not properly attributed in many cases. More information on Josh’s ongoing efforts here and here.

RADIUM AGE TIMELINE: [1900 | 1901 | 1902 | 1903] | 1904 | 1905 | 1906 | 1907 | 1908 | 1909 | 1910 | 1911 | 1912 | 1913 | 1914 | 1915 | 1916 | 1917 | 1918 | 1919 | 1920 | 1921 | 1922 | 1923 | 1924 | 1925 | 1926 | 1927 | 1928 | 1929 | 1930 | 1931 | 1932 | 1933 | [1934 | 1935]. (The brackets, here, indicate “interregnum” years — i.e., periods of overlap between sf’s Radium Age and its Scientific Romance and so-called Golden Age eras.)

The year 1924, in my periodization scheme, marks the beginning of the cultural decade known as the “Twenties.” Of course there are no hard stops and starts in culture, so it’s more accurate to describe 1924 (and 1923) as cusp years during which the Teens end and the Twenties begin.

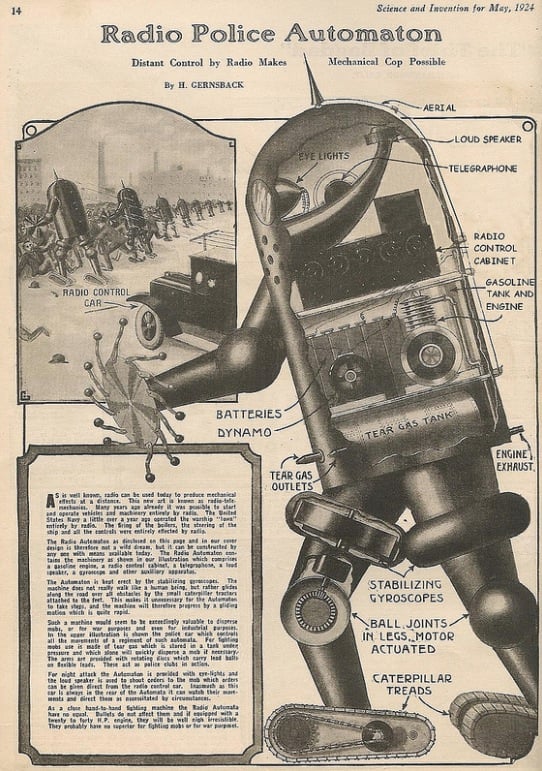

Gernsback’s The Experimenter – originally Practical Electrics, the first issue under this title was November 1924; merged into Science and Invention in 1926. In 1924 Gernsback sent a letter to subscribers suggesting a magazine that would publish only scientific fiction. The response was weak, and Gernsback shelved the project for two years (see 1926).

As early as February 1924, Farnsworth Wright took over as interim editor of Weird Tales (see 1923). The magazine went on hiatus while ownership issues were resolved. Weird Tales resumed publication with the November 1924 issue, with Farnsworth Wright as permanent editor. The magazine quickly began to improve, both in appearance and quality, as Wright nurtured talented fantasy writers such as Robert E. Howard and H.P. Lovecraft. Wright frequently published science fiction, including Edmond Hamilton’s first story, which appeared in August 1926, and work by J. Schlossel and Otis Adelbert Kline, as well as weird and occult fiction.

Proto-sf coinages dating to 1924, according to the Historical Dictionary of Science Fiction: ROBOTICALLY (in the manner of a robot; mechanically; without emotion) | SPACE-BORNE (travelling or carried through space; also, carried out in space or by means of instruments in space) | SPACE ROCKET (a rocket designed to travel beyond a planet’s atmosphere).

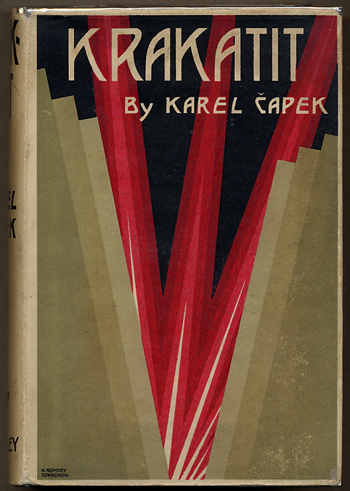

- Karel Čapek’s Krakatit (1924). When a Czech engineer, Prokop, invents an explosive which releases the destructive energy contained in atoms, and which can destroy entire cities, he is wooed and pursued by those — a wealthy munitions manufacturer, a beautiful anarchist, a villain who may be the Devil himself — who would control it. A dreamlike, absurdist, volatile admixture of romance, adventure, and philosophy, Krakatit warns that with technological advances comes unforeseen temptations and consequences. “Do you want to rule the world?” demands the villain, of Prokop. “Good. Do you want to annihilate the world? Good. Do you want to make the world happy by forcing upon it eternal peace, God, a new order, revolution, or something of the sort? Why not?” In the end, a horrific explosion occurs. Fun facts: Elsewhere, I have argued that this novel’s 1925 British dustjacket is one of the greatest Radium Age science fiction cover designs; it captures both the excitement and terror of breakthrough technology.

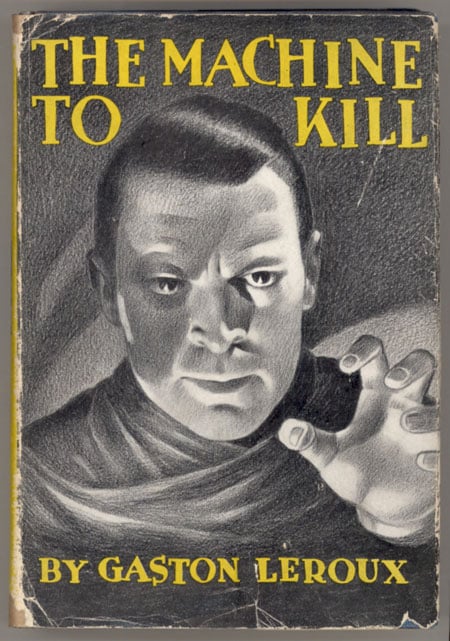

- Gaston Leroux’s The Machine to Kill (1924; in English, 1935). Dr. Jacques Cotentin, who apparently hasn’t read Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, is working on a part-human, part-mechanical man, with the invaluable aid of his future father-in-law, a clockmaker (whose name, uncannily predicting the work of the American mathematician and philosopher who pioneered cybernetics, is Norbert). Thanks to radium-infused serum and the brain and nervous system of Benedict Masson, a frightening-looking recluse who’d been found guilty, without any definitive proof, of several gory murders and recently guillotined, the creature comes to life! Masson, that is to say, finds himself alive and well — and inhabiting a body that is stronger than six men, and impervious to pain. “Gabriel,” as the creature is named, bursts loose from captivity, wreaks havoc in Paris, then vanishes… along with Christine, Cotentin’s fiancée. Gabriel must open his own chest cavity and wind up his gears once per day, which is a creepy, fun idea. More gory murders occur, in the area where Masson’s murders happened — so Lebouc, a former police detective who now wants to be a reporter, investigates. Sounds straightforward enough, but there’s also a Blavatsky-like cult of influential Frenchmen obsessed with Hindu lore… how are they involved? Fun fact: Leroux is best known for his 1909 horror tale, Le Fantôme de l’Opéra.

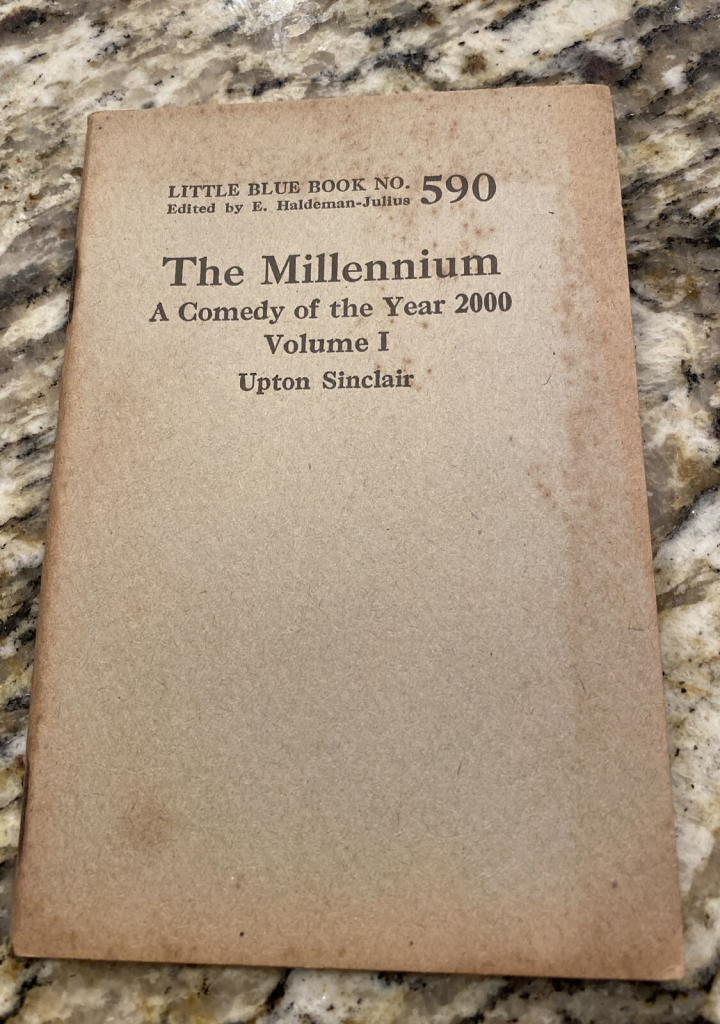

- Upton Sinclair’s The Millennium (1924 edition). In 1907, Upton Sinclair wrote The Millennium, a comedic yet serious-minded play that looks forward to the year 2000 — at which point a “radiumite” explosion will kill everyone in the world except eleven people… who experiment with one sociopolitical system after another: Socialism, Communism, Capitalism, Feudalism, survivalism. Finally, three of the survivors — led by poor but resourceful Billy Kingdom — establish a utopian colony. In 1924, Sinclair rewrote the play as a novel. Fun fact: In 1906, Sinclair plowed the proceeds from his bestselling novel The Jungle into Helicon Home Colony, an artistic commune in New Jersey; it burned down in ’07. The utopian colony at the end of The Millennium bears a striking resemblance to Helicon.

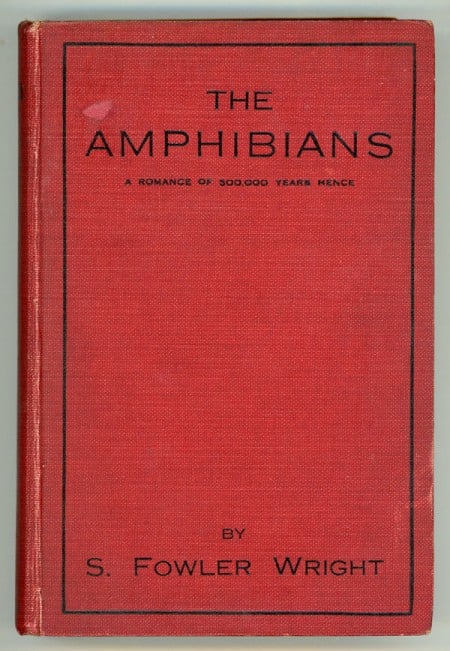

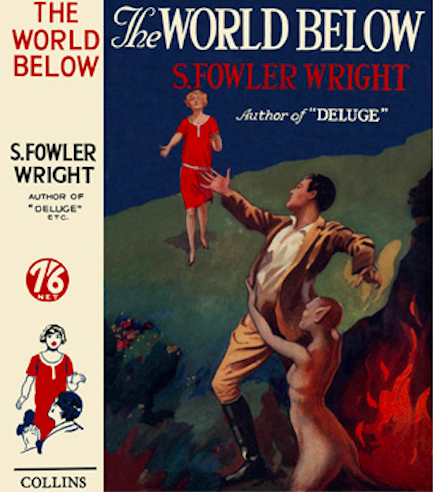

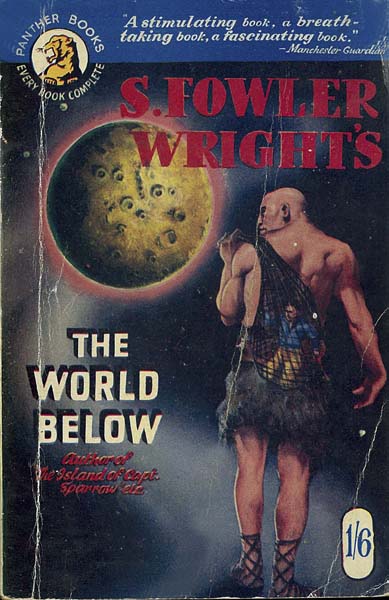

- S. Fowler Wright’s Radium Age sci-fi adventure The Amphibians (serialized 1924–1925). Half a million years from now, George, a time-traveling human — yes, he’s read H.G. Wells’s The Time Machine — discovers that the Earth’s dominant intelligent species are the Dwellers (giant troglodytic humanoids self-destructively devoted to science) and the Amphibians (otter-like, telepathic creatures who are morally more evolved than humans). Humankind as we know it, it seems, was not the endpoint of evolution — only a stage to overcome. In search of two previous time travelers who’ve failed to return, George is befriended by a peaceful, gender-fluid Amphibian who regards him as a puzzling, limited, violently emotional, rather grotesque and pathetic creature. This Kirk-and-Spock duo traverses the future Earth — a landscape of nightmarish, carnivorous flora and fauna, the depiction of which was no doubt influenced by Wright’s translation of Dante’s Inferno — while debating social, cultural, economic, and moral questions. Eventually, George comes to agree with the Amphibian regarding 20th-century humankind’s foibles; the book’s overall message is more or less a libertarian or anarchistic one. All living creatures are capable of harmony and freedom, if only we’d stop being assholes. The story ends abruptly, with no sign of the missing time travelers; in 1929, Wright published The World Below, which adds a sequel — titled The Dwellers — to The Amphibians. A third installment was never completed. Fun fact: Wright was one of the key figures in the tradition of British scientific romance; Everett F. Bleiler calls The World Below “undoubtedly the major work of science fiction between the early Wells and the moderns.” Wright’s family maintains an impressive website featuring his poetry and fiction.

- Hannah Coron’s Two Years Hence? London: See this list of Pre-1950 Utopias and Science Fiction by Women.

- Lady Dorothy Mills’s The Arms of the Sun. Lost race novel set in Africa. See this list of Pre-1950 Utopias and Science Fiction by Women.

- Perkins, Violet Lilian and Hood, Archer Leslie [United States]

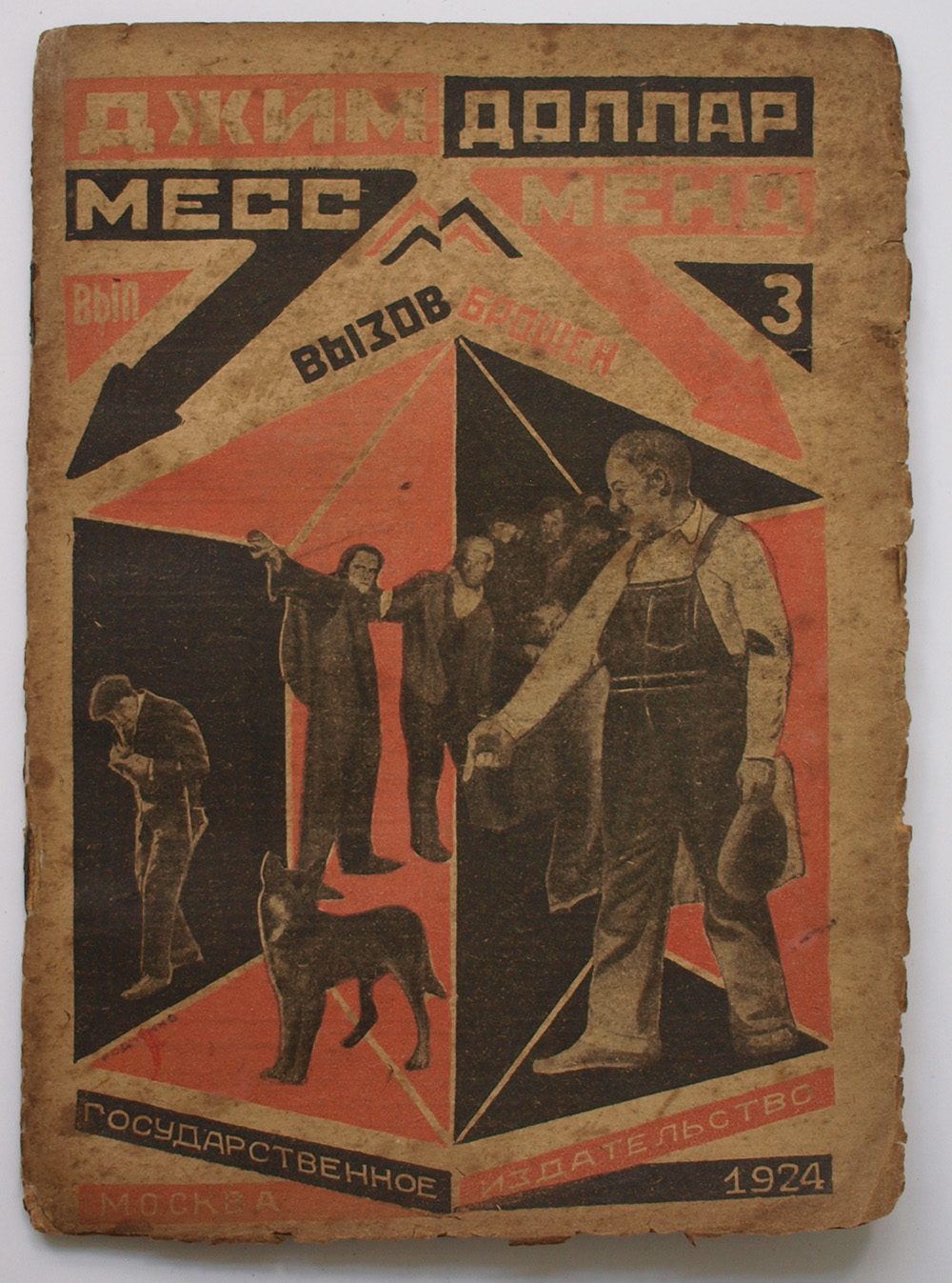

The Melody from Mars. By Lilian Leslie. [joint pseud.] New York: Authors’ International Pub. Co., 1924. See this list of Pre-1950 Utopias and Science Fiction by Women. - Marietta Shaginyan’s Месс-менд, или Янки в Петроград (Miss Mend, or Yankees in Petrograd). Shaginyan, a Moscow-born author of Armenian descent, was one of the era’s most important communist writers experimenting in satirico-fantastic fiction. This is the first in a trilogy of “proletarian detective novels” parodying the sort of US crime/spy thrillers then being published in The Black Mask and other pulps. Western capitalists and deposed Russian nobles plotting to assassinate Lenin and the Soviet government are foiled not only by a secret American workers’ organization but by a degenerative disease that turns the conspirators into beasts. Published under the cheeky nom de plume “Jim Dollar” in ten fascicules under the title, then in one volume in 1956. Alexander Rodchenko created extraordinary photomontage cover designs for the original serialization.

- Sarah Norcliffe Cleghorn’s “Utopia Interpreted” in The Atlantic Monthly. See this list of Pre-1950 Utopias and Science Fiction by Women.

- Rena Oldfield Pettersen’s Venus. See this list of Pre-1950 Utopias and Science Fiction by Women.

- Alfred Döblin’s Berge Meere und Giganten. Deals with genetic engineering as a means of evolving the capacities of a future race of humans. “A strange, hectic and visionary chronicle of future European history, spanning several centuries… Thematically similar to Stapledon, the novel is closer in spirit to the work of Cordwainer Smith, who is said to have admired it greatly.” – Anatomy of Wonder. “… Astark and wild vision of the coming wars in Europe, the clash of ideologies and races, and the titanic attempts of humankind to refashion genetically the human body. In the breadth of its scope and vision, the book is sometimes reminiscent of Olaf Stapledon, but it is much more powerful.” – Rottensteiner. “The most celebrated of the writers who occasionally experimented with SF themes was Alfred Doblin … Two of his books are surreal, metamorphic SF of very considerable power: WADZEKS KAMPF MIT DER DAMPFTURBINE (1918) and BERGE MEERE UND GIGANTEN (1924). Funf act: Döblin was not satisfied with this version of his novel and published a revised text as GIGANTEN, EIN ABENTEURBUCH in 1932.

Berge Meere und Giganten (Mountains Seas and Giants) is a 1924 science fiction novel by German author Alfred Döblin. Stylistically and structurally experimental, the novel follows the development of human society into the 27th century and depicts global-scale conflicts between future polities, technologies, and natural forces, culminating in the catastrophic harvesting of Iceland’s volcanic energy in order to melt Greenland’s ice cap. Among critics, Berge Meere und Giganten has the reputation of being a difficult and polarizing novel, and has not received nearly as much attention as Döblin’s following novel, Berlin Alexanderplatz (1929).

- Joseph Gray Kitchell’s The Earl of Hell. A scientist compounds an antigravity material which is stolen by a foreign power. An overused theme by the 1920s. However, the novel is “unusual in stressing physical properties of the metal and its commercial exploitation, rather than using it as a device for adventures. As fiction, routine work, although the author seems to be better versed in the physical sciences than most authors who wrote about radium at this time.” — Bleiler

- M.P. Shiel’s The Lord of the Sea. Among Shiel’s most important and popular books. “…. With the aid of a cache of diamonds recovered from a meteorite [Richard Hogarth] finances the building of giant floating fortresses that give him command of the sea-lanes. He uses this advantage to blackmail the nations into peace and social progress… THE LORD OF THE SEA is exceptional in offering an elaborate account of the reforms demanded by Hogarth.” – Stableford, Scientific Romance in Britain 1890-1950. “A brilliantly, highly imaginative work, conveying conviction despite its belated adherence to an early aesthetic of melodrama.” – Bleiler.

- J. Lionel Tayler’s The Last of My Race. “A man awakens after a half-million years, in surroundings that are meant to imitate those of his own period. (The details are ‘uncannily like, and equally uncannily not like.’) He is the last member of his race, and he is encouraged to write down this first-person account, more as a way of coming to terms with his own situation, to preserve his sanity for the brief remainder of his life, than as a communication to anyone else now alive, whose frame of reference is so profoundly different from his own as to render him a member of a different (and extinct) species. As a utopian tale of the far future, it is notable on several counts: its brevity (this is a novella, really), its succinctness, its easy readability, its omission of the usual ‘tour-guide’ to explain the new society (and turn the narrative into an essay), its emphasis on the alien quality of the new world, taking it beyond those terms that could let us see it as either utopian or dystopian. Also, by setting the story in a manufactured facsimile of the familiar world rather than setting forth the usual futuristic/utopian furniture (e.g., men and women in white flowing robes; airships and other gizmos, all powered by electricity; tediously detailed explanations of the new improved legislatures, telephones, sewage treatment systems, etc.), the author adds another level of meaning to the story, making it a powerful allegory about the alienation of existence in the present-day world. Tayler would not have been the only person in postwar Europe who felt profoundly alienated from a world that was evolving away from the familiar at a frightening and accelerating speed; but he was the only one who expressed that alienation in an imaginative work of this nature. A very interesting book.” – Robert Eldridge. “Evolution and the far future… In some ways a remarkable work that should receive more attention than it has. The author conveys well the emotional strain of the narrator and adds many imaginative touches that anticipate later science-fiction, notably Olaf Stapledon.” – Bleiler

- Martin Hussingtree’s Konyetz. Apocalyptic novel of world war, the Black Plague, and the end of the world. A prejudicial novel forecasting the end of western civilization (“Konyetz” is Russian for the End), as the Jewish-Bolshevik conspiracy steamrollers its way across Europe and into a Labour-governed Great Britain bombing and gassing as it goes. Fun fact: Martin Hussingtree is a pseudonym of Oliver Baldwin, whose father (Stanley Baldwin) was a three-time British Prime Minister.

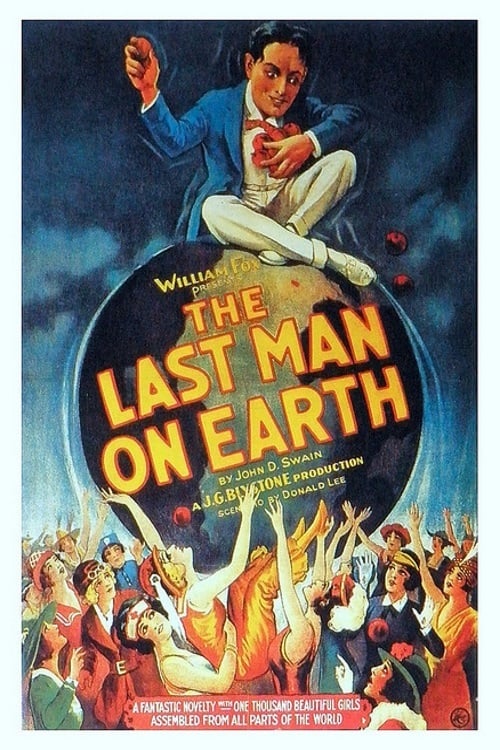

- The Last Man on Earth is a 1924 American silent comedy film directed by John G. Blystone, starring Earle Foxe and produced by Fox Film Corporation and based on the short story of the same name by John D. Swain that appeared in the November 1923 issue of Munsey’s Magazine. In 1940, Elmer Smith (Foxe) proposes to Hattie (Perdue), his childhood sweetheart, and she turns him down, saying that she would not marry him if he were the last man on earth. He jumps in his plane, determined to go where there are no women. A strange disease known as “masculitis” develops that kills all the males over fourteen years old. Women now run the world. Ten years later, Gertie (Cunard), a gangster, while fleeing from the police finds herself in a forest and discovers Elmer, who has been living as a hermit. She brings him back and, after he is examined at a hospital, the government buys him for $10,000,000 as he is the last man on earth. Then arises the problem of what to do with him.

- Vladimir Obruchev’s Plutonia (Плутония). It was written in 1915 in Kharkov and first published in the original Russian in 1924. The title Plutonia refers to the novel’s setting in a lost land. It is an underground world having its own sun, called Pluto for the Roman god of the underworld. The terrain is marked by dramatic geographic features and inhabited by prehistoric animals and primitive people.

- Rokeya Sakhawat Hossain’s Padmarag (পদ্মরাগ — The Ruby, or Essence of the Lotus), a Bengali-language feminist and anti-colonialist utopian novella set in Tharini’s House — a women-run school, boarding house, and welfare center in Bengal. The staff of Tharini’s House are progressive activists who aim to provide equal opportunities for female students, regardless of their ethnicity, religion, region, class or caste. Moreover, the instructors resist the colonialist dictates of their students’ parents, who wish only for their daughters to “speak fancy,” which is to say, to speak English with a posh accent. All women, whether Hindu, Muslim, or Christian, whether south Asian or European, are victims of oppression, we come to understand as we follow the diverse characters’ various storylines. The best possible remedy to this sorry state of affairs? A nonsectarian, inclusive and self-supporting “arcology” — to use a term popularized more recently by sf authors — directed and staffed by women. See my essay on Begum Rokeya, from which this description is excerpted.

- José Moselli’s “Le messager de la planète” is about an alien from Mercury who crash-lands in Antarctica and is discovered by explorers (in the end he is killed and eaten by their dog-team). Fun fact: Joseph Théophile Maurice Moselli (1882-1941), was a prolific writer of adventure fiction of all sorts for the French pulps. He wrote mostly as José Moselli.

- José Moselli’s “Le voyage éternel ou les prospecteurs de l’infini” tells the story of a lunar expedition that fails to return home.

- H. M. Egbert (Victor Rousseau Emanuel)’s Draught of Eternity. Originally published as a serial 1-22 June 1918 in ALL-STORY WEEKLY as “The Draft of Eternity” by Victor Rousseau. “Science fiction novel in which a drug, a variant of cannabis, projects the hero into a New York of thousands of years in the future and under Mongol rule.” – Locke, A Spectrum of Fantasy. “Fine novel of the far future when catastrophe has thrown the world back into a medieval society, and the time traveling potion has turned the hero into a burly, Conan-like hero.” – Leon Gammell

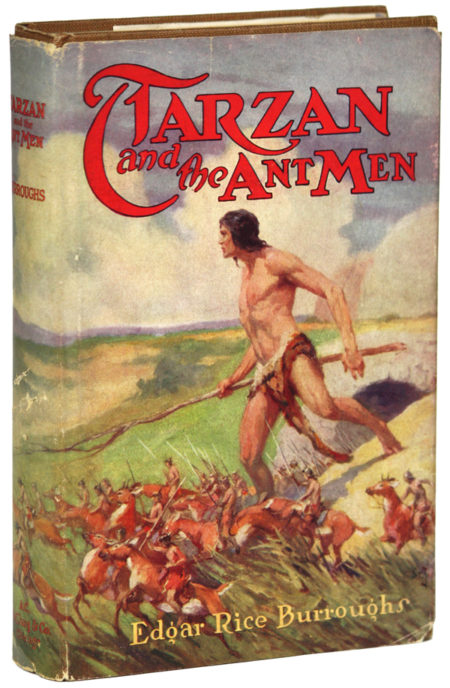

- Edgar Rice Burroughs‘s Radium Age sci-fi/Tarzan adventure Tarzan and the Ant Men. I’m very fond of the oddball, later Tarzan adventures — this is the 10th in the series. Here, Tarzan stumbles upon a lost tribe — the Minuni, normally proportioned Caucasian humans who happen to be 18 inches tall, and who are divided into civilized, advanced yet rivalrous city states. (Shades of the Lilliputians and Blefuscudians, in Gulliver’s Travels.) They are ferocious warriors, who ride on small antelopes; and they live in beehive-like structures. The Minuni practice slavery, but according to their tradition, members of the royal family may only marry and breed with slaves… which has led to the practice of raiding one another’s cities, enslaving beautiful women, and marrying them. Tarzan befriends the king, Adendrohahkis, and the prince, Komodoflorensal, of one such city-state, called Trohanadalmakus; he is captured in battle by the Veltopismakusians, whose brilliant scientist uses vibration-disks to shrink Tarzan down to their size. Like DC’s The Atom, who wouldn’t make his comic-book debut until 1961, Tarzan retains his full-size strength — which makes him a kind of superhero figure among the Minuni. This is the last novel in the sequence that began with Tarzan the Untamed (1919–1920), in which Burroughs’ imagination and storytelling abilities are at their peak; it’s a fan favorite — Harper Lee describes Scout reading it in To Kill A Mockingbird.Fun facts: First published as a seven-part serial in Argosy All-Story Weekly, and published in book form the same year. The book was adapted into comic form by Gold Key Comics in Tarzan nos. 174-175 (June–July 1969), with art by Russ Manning.

- Algernon Blackwood’s “Malahide and Forden” — story about time and space. Malahide, Forden, and our narrator, Hubert, one April day go for a walk to Barton-in-Fabis. The story “puzzles, baffles, intrigues the reader; even while reveling in the sheer loveliness of the descriptions,” according to a contemporary reviewer of Tongues of Fire, the 1924 collection in which this story appears. “One is perplexed and tantalized by one’s inability to grasp the meaning of it all. And then, in the very last paragraph, half a dozen sentences make it all clear. Everything that has gone before falls into place, seen in the light of this revelation. The tale is a triumph of that discerning of unseen forces, that power of describing the all but indescribable, so uniquely Mr. Blackwood’s own.”

- Algernon Blackwood’s “Playing Catch” — story about time and space.

- H.G. Wells’s The Dream. Twenty centuries in the future a tourist cuts his hand in the ruins of the “Ages of Confusion.” In a fever induced dream he experiences “a whole life in that old world.”

- B. Wallis’s The Abysmal Horror (in Jan-Feb 1924 Weird Tales). Bruce Wallis and his cousin, George C. Wallis, were cousins who often wrote in tandem. Alien life form menaces Earth’s oceans.

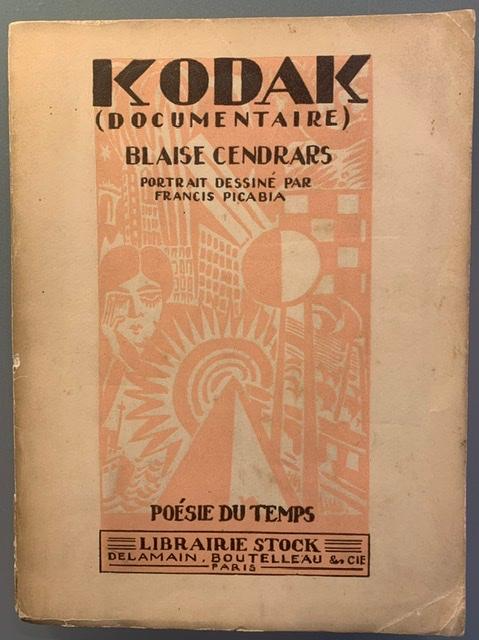

- Blaise Cendrars’ Kodak (Documentaire). A poetry collage assembled — though this was not made clear at the time — from snippets of Gustave Le Rouge’s 1922 proto-sf novel Le Mystérieux Docteur Cornelius [see 1922]. Published with a cover design employing occult motifs by Frans Masereel and frontispiece portrait by the avant-garde (mostly Cubist) painter and poet Francis Picabia, Kodak comprises sixty-three poems that look like simple vignettes caught by the poet during his travels to the U.S. and beyond, and put down on paper with the apparent immediacy of a tourist’s photographic record. Fun fact: The publisher was sent a cease-and-desist by the Kodak Co.

- Gaston Leroux’s La Poupée Sanglante: Roman d’aventures et de mystere. Leroux’s last proto-sf novel of interest, and apparently a bestseller at the time. First published in two parts (1 July-9 August 1923 Le Matin; 1924; trans. anon. as The Kiss That Killed in 1934). A romantic mystery about a love triangle, a creepy library, and a twisted crime. It features a poet voyeur who climbs a ladder to peer out of his narrow skylight at a beautiful maiden who lives next door in the celebrated Hôtel de Hesselin, a maiden who’s caught up in a louche love affair and scientific experiment, some Frankenstein-style body remaking, a vampire, a mass murder with butchery, and wonderfully evocative descriptions of the crumbling, grimy Ile Saint-Louis. There are major mysteries: that of the seven disappearing women (solved in a fragmentary fashion that leaves much to the imagination); the strange illness and death of the Marquise de Coulteray (involves proto-sf vampires); and the creature who is known as Gabriel.

- Hugh Kingsmill’s collection of novellas The Dawn’s Delay. “Comprising ‘The End of the World,’ ‘Disintegration of a Politician’ and ‘W. J.’ and ‘The Return of William Shakespeare’.” “The End of the World” is a Withnail and I-like humorous story about two Englishmen in France who believe that a comet is about to strike the Earth; although we hear a bit about how the solar system is inhabited by various species, it’s all for laughs. “W.J.” is about a future war. Fun fact: “Dawnist” was Kingsmill’s word for those infected with utopian idealism — the enemy as far as he was concerned. Kingsmill was a novelist, biographer, essayist and literary critic — best remembered as the creator of the still-famous An Anthology of Invective and Abuse.

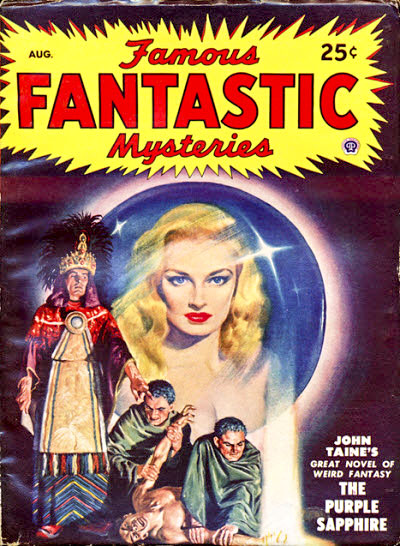

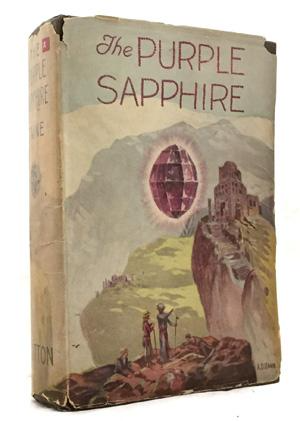

- John Taine’s The Purple Sapphire. Evelyn, an English general’s daughter who was eight at the time, was kidnapped 12 years ago in India; the general’s servant Singh seems the likely candidate. Adding to the mystery is a large sapphire left behind by the servant in a metal box with unknown writing on it. John Ford and his niece Rosita Rowe, American gem-hunters and explorers, are enlisted to seek out Evelyn; they are joined by Captain Joicey, who has been found delirious, babbling in an unknown language and clutching another large sapphire. Joicey, it turns out, has discovered a lost world tale — Tibetans who can turn sandstone into sapphires by the use of a mysterious ray, technology developed by their more advanced ancestors. Will the group find riches? Will they be able to find Evelyn and return with her to civilization? The story was later reprinted in Famous Fantastic Mysteries in 1948. Fun fact: Taine is mathematician Eric Temple Bell (1883 — 1960). This is his first novel.

- Valentin Katayev’s Povelitel’ zheleza [“Iron Master”] (1924; 1925). Katayev (1897–1986) was a Soviet novelist and playwright whose lighthearted, satirical treatment of postrevolutionary social conditions rose above the generally uninspired official Soviet style.

- Noëlle Roger’s (pseudonym of Swiss author Hélène Dufour Pittard, 1874-1953) The New Adam. A wholly logical and unpleasant superman created by gland transplants. FAfter having invented a nuclear force field, he blows himself up.

- Otfird von Hanstein’s Die Farm der Verschollenen (The Hidden Colony). Appeared in Wonder Stories, January–March 1935, tr. Fletcher Pratt). Bleiler notes von Hanstein’s focus on “technology as a way of improving efficiency and life” and wrote that “The frame situation is somewhat confusing, and the characterizations are weak, but the technology is at times fascinating. Like Hanstein’s other stories, stodgy, but readable”.

- Philip M. Fisher’s “Beyond the Pole” (May 1924 Munsey’s Magazine). A novella in which members of an expedition to the North Pole by airship finds themselves trapped in a vortex of electricity that eventually makes them all invisible.

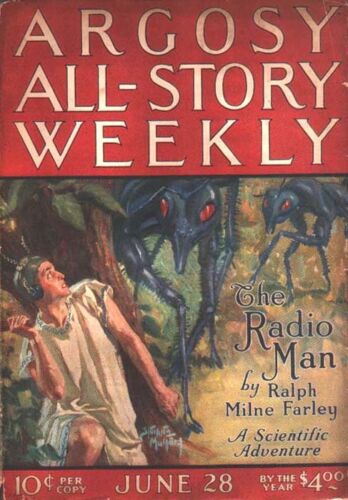

- Ralph Milne Farley’s (pseudonym of US constitutional lawyer, author and teacher Roger Sherman Hoar) The Radio Man. The first instalment of his most famous series, the Radio Man Planetary Romances featuring Miles Cabot, which continued with The Radio Beasts (21 March-11 April 1925 Argosy), The Radio Planet (26 June-24 July 1926 Argosy All-Story Weekly), The Radio War (2-30 July Argosy All-Story Weekly), etc. The sequence, at first absurdly boosted by The Argosy as scientifically accurate, is devoted to the adventures of Cabot, mostly on Venus, the Radio Planet. After being accidentally shifted to that planet via matter transmitter, Cabot quickly frees its humanoid inhabitants from domination by an ant-like race; after marrying a human princess, he continues his activities ad libitum, though sometimes his son takes over.

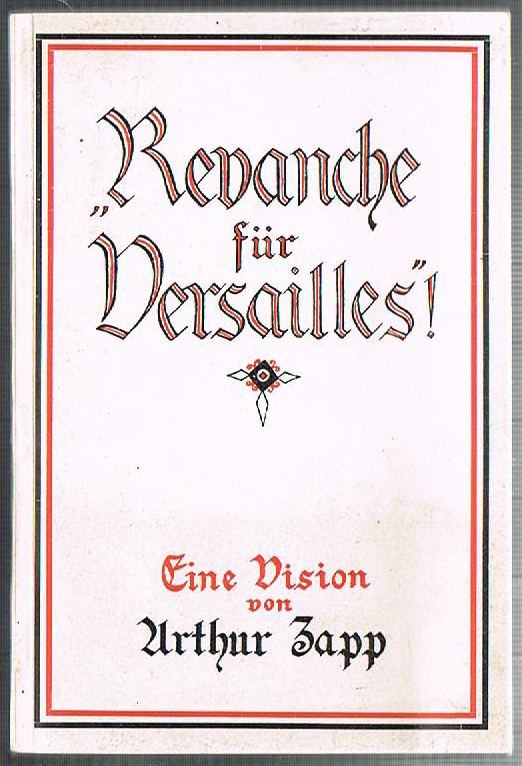

- Arthur Zapp’s Revanche fur Versailles! An ironically titled prophetic vision of a second world war by a leftist visionary who perceptively diagnosed Germany’s radical nationalist consciousness and the special appeal that nationalist ideas held for youth. A bleak vision critical of German militarism and fearful that the pacifist call for reason and civilization would go unheard due to the superior strength of the anti-pacifist, nationalist forces. The ensuing conflagration exceeds the First World War in its destructiveness. “Only through the horrors of a second world war, Zapp predicted, would mankind finally come to its senses … Despite his pessimism, Zapp ended with the hopeful image of a genuinely desired and effective international union that binds humanity together after learning a bitter lesson from the second world war. The Kulturpartei evolves into the Weltpartei, reflecting the new consciousness that all mankind is tied together. Zapp’s last plea was that ‘we ought not to consider ourselves civilized until we stop desecrating science and technology by using them to annihilate that which is most valuable to man: life.'” – Fisher, Fantasy and Politics: Visions of the Future in the Weimar Republic

- Andrei Marsov’s Love in the Fog of the Future. See Drozdz’s essay on “Parodies of Authority in the Soviet Anti-Utopias from 1918-1930.”

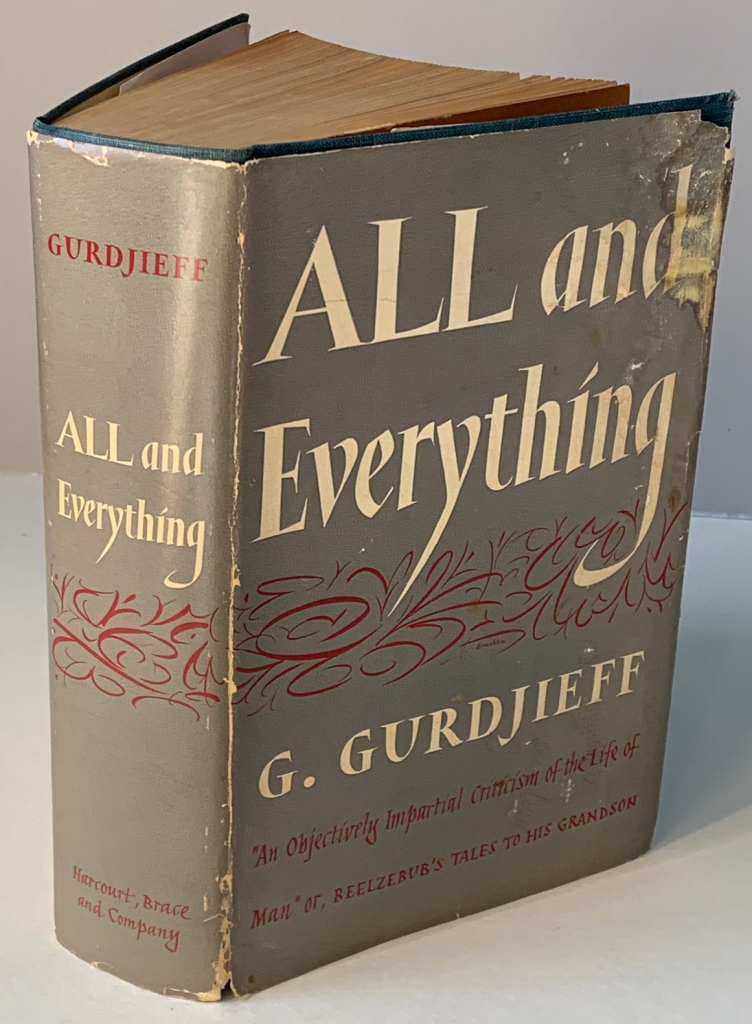

- George Gurdjieff’s Beelzebub’s Tales to His Grandson. Having migrated for four years after escaping the Russian Revolution with dozens of followers and family members, Gurdjieff settled in France and established his Institute for the Harmonious Development of Man at the Château Le Prieuré at Fontainebleau-Avon in 1922. The institute was an esoteric school based on Gurdjieff’s Fourth Way teaching. After nearly dying in a car crash in 1924, he closed down the Institute and began writing the three-part Beelzebub’s Tales to His Grandson (“An Objectively Impartial Criticism of the Life of Man”), itself the first part of the never-completed All and Everything, in a mixture of Armenian and Russian. The goal of Beelzebub’s Tales, which is at least in part a proto-sf novel, was to “destroy, mercilessly, without any compromises whatsoever, in the mentation and feelings of the reader, the beliefs and views, by centuries rooted in him, about everything existing in the world.” He would abandon the project in 1935 before finishing the third volume of All and Everything. Beelzebub’s Tales to His Grandson is a (semi-autobiographical?) narrative focusing on Beelzebub, who while en route to another planet in his starship synopsizes for his grandson’s benefit the history of planet Earth and of its “three-brained” inhabitants. Excerpt:

Through the Universe flew the trans-space communication ship Karnak.

Having left the spaces of the “Assooparatsata,” that is, the “Milky Way,” it was flying from the planet “Karatas” to the solar system “Pandetznokh,” the sun of which is called the “Pole Star.”

On this trans-space ship was Beelzebub with his kinsmen and close companions.

He was on his way to the planet “Revozvradendr,” to a conference in which he had consented to take part, at the request of friends of long standing.

Only the remembrance of these old friendships had induced him to accept the invitation, for he was no longer young, and so lengthy a voyage with its inevitable hardships was by no means an easy task for one of his years.

According to the SFE, this book “may or may not be a consciously equipoisal attempt to marry metaphysics and sf; it is, however, sufficiently unsettling to register as such an effort.”

- Ray Cummings’s The Man Who Mastered Time. Perhaps his best time travel story?

- Rose Macaulay’s Orphan Island is a near-future borderline utopia describing in retrospect a teacher’s tyranny over her forty pupils after they are shipwrecked on a remote Pacific Island in 1855; the satire of conventional Victorian social and sexual mores is very pointed. After the teacher’s death at a great age in 1925, a republic is announced, the name of the land is changed from Smith Island to Orphan Island, and flourishes.

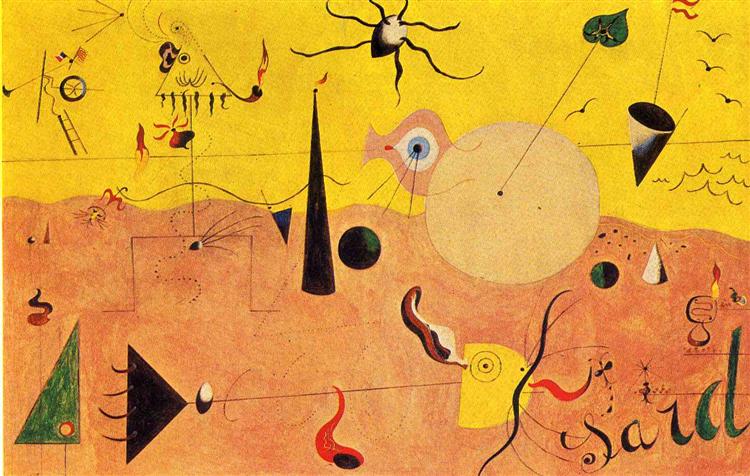

Miró’s iconographic forms, such as the pipe-smoking hunter on the left, are more than just abstractions and have become something like symbols.

ALSO: Edwin Hubble announces that Andromeda is a galaxy, and that the Milky Way is only one of many such galaxies in the universe; J.B.S. Haldane coins the term “ectogenesis” (influential on sf). In his PhD thesis, Louis de Broglie postulates the wave nature of electrons and suggests that all matter has wave properties; this concept forms a central part of the theory of quantum mechanics. Hourly time signals from Royal Greenwich Observatory are broadcast for the first time. Ford Motor Company produces 10 millionth car. Coolidge elected US president; J. Edgar Hoover becomes director of the FBI. P.C. Wren’s Beau Geste, John Buchan’s The Three Hostages, Richard Connell’s “The Most Dangerous Game.” E.M. Forster’s A Passage to India. Marinetti’s Futurismo e Fascismo. D.W. Griffith’s The Ten Commandments, De Mille’s The Thief of Bagdad, Buster Keaton’s The Navigator. Harold Gray’s comic strip Little Orphan Annie makes its debut. The American Mercury magazine founded.

Hans Berger (1873 – 1941) was a German psychiatrist. He is best known as the inventor of electroencephalography (EEG) in 1924, which is a method used for recording the electrical activity of the brain, commonly described in terms of brainwaves, and as the discoverer of the alpha wave rhythm which is a type of brainwave. His research theme was “the search for the correlation between objective activity in the brain and subjective psychic phenomena” — in fact, he started out looking for a locus in the brain for “psychic energy” that might explain his sister’s telepathy.

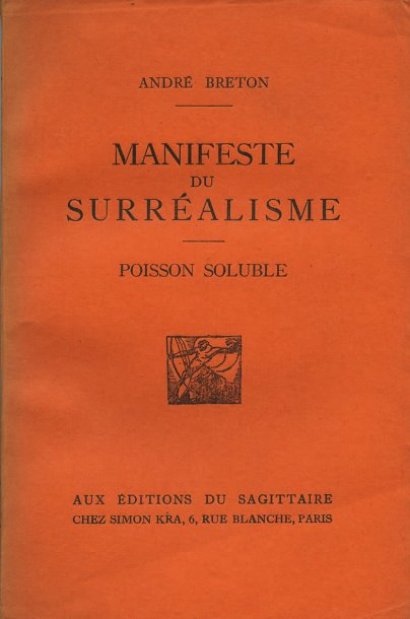

The term “surrealism” originated with Apollinaire in 1917. However, the Surrealist movement was not officially established until after October 1924, when Breton published his Surrealist Manifesto. Although Einstein’s cold and elegant concept of Space-Time had more or less replaced the spatial fourth dimension in the minds of the public, the Surrealists continued to make reference to it — as an act of rebellion and vindication of the absurd.

[T]he realistic attitude, inspired by positivism, from Saint Thomas Aquinas to Anatole France, clearly seems to me to be hostile to any intellectual or moral advancement. I loathe it, for it is made up of mediocrity, hate, and dull conceit. It is this attitude which today gives birth to these ridiculous books, these insulting plays. It constantly feeds on and derives strength from the newspapers and stultifies both science and art by assiduously flattering the lowest of tastes; clarity bordering on stupidity, a dog’s life. The activity of the best minds feels the effects of it; the law of the lowest common denominator finally prevails upon them as it does upon the others.

— Andre Breton, Manifesto of Surrealism

Surrealism showed up in the aftermath of WWI with a significantly different energy and purpose vs. the Futurists, Vorticists, and Dadaists. Their concerns were serious, and they were committed to dialogue with the “other” — see Breton’s 1924 Manifesto of Surrealism, which talks about “re-eestblishing dialogue with the absolute truth by freeing both interlocutors [that is, the surrealist and the absolute truth itself] from any obligation of politeness.”

In 1924 Breton published his Manifeste du surréalisme, and the first issue of the newly organized group’s review La Révolution surréaliste. (He also brought out his first collection of critical and polemical essays.) In contrast to the avant-garde typography of dadaist tracts this new journal deliberately set itself up to resemble a scientific periodical. Reports on dreams, examples of automatic writing, games.

They were also politically engaged — they attacked French colonialism and nationalism, they sought to reconcile orthodox Marxism with avant-garde experimentation, they were anti-fascist and later anti-Stalinist.

I’d connect surrealism and abstract art in that Surrealist paintings often exhibit a deeply mysterious atmosphere, with unexplained elements that seem to refer to something else seen, read or imagined beyond the canvas. Objects seem to symbolize something; there are symbols and hieroglyphic signs. Diametrically and sometimes more subtly opposed elements. Traces, tracks and signals point outward and inward. Objects in the world seem to carry a charge of something unspoken — perhaps threatening.

E A. Burtt’s The Metaphysical Foundations of Modern Physical Science (1924/1925) is a critique of logical positivism that would influence the historian and philosopher of science Alexandre Koyré, and through Koyré the philosopher of science Thomas Kuhn. Burtt argues that there is “no escape from metaphysics.” That is, science must account for subjective perspectives, since all objective conclusions are ultimately founded upon the subjective conditioning/worldview of its researchers and participants.

Waldo Frank’s 1924 essay “For a Declaration of War” gives a place to non-Euclidean geometries in the emergent new culture. Frank here argues tha Western culture was in a state of dissolution — that the “basal assumptions” once shared by all of its members were in the process of breaking up: Copernicus had relegated the world to a minor corner of the universe; Kant had disproved the validity of the senses; Darwin had denied man the title of Lord of Creation; Freud had robbed man of his reason, and Marx of his free will; and Einstein had unstabilized the concepts of time, energy, and matter. The modern world, which was the end product of this cycle of decay, was for Frank a “chaos of sterile facts,” a “multiverse” populated by “atomic wills,” a world empty of any order or values whatsoever. In the face of such a disaster, Frank saw no cause for despair, but instead interpreted the chaos itself as a sign not only of decay, but also of gestation. “The old spiritual body is breaking up. Ere we can be whole and hale again, we must create a new spiritual body. And that means birth.”

MORE RADIUM AGE SCI FI ON HILOBROW: HiLoBooks homepage! | What is Radium Age science fiction? |Radium Age 100: 100 Best Science Fiction Novels from 1904–33 | Radium Age Supermen | Radium Age Robots | Radium Age Apocalypses | Radium Age Telepaths | Radium Age Eco-Catastrophes | Radium Age Cover Art (1) | SF’s Best Year Ever: 1912 | Radium Age Science Fiction Poetry | Enter Highbrowism | Bathybius! Primordial ooze in Radium Age sf | War and Peace Games (H.G. Wells’s training manuals for supermen) | Radium Age: Context series | J.D. Beresford | Algernon Blackwood | Edgar Rice Burroughs | Karel Čapek | Buster Crabbe | August Derleth | Arthur Conan Doyle | Hugo Gernsback | Charlotte Perkins Gilman | Cicely Hamilton | Hermann Hesse | William Hope Hodgson | Aldous Huxley | Inez Haynes Irwin | Alfred Jarry | Jack Kirby (Radium Age sf’s influence on) | Murray Leinster | Gustave Le Rouge | Gaston Leroux | David Lindsay | Jack London | H.P. Lovecraft | A. Merritt | Maureen O’Sullivan | Sax Rohmer | Paul Scheerbart | Upton Sinclair | Clark Ashton Smith | E.E. “Doc” Smith | Olaf Stapledon | John Taine | H.G. Wells | Jack Williamson | Stanisław Ignacy Witkiewicz | S. Fowler Wright | Philip Gordon Wylie | Yevgeny Zamyatin