RADIUM AGE: 1922

By:

September 18, 2022

A series of notes — Josh calls it a “timeline,” but Kulturfahrplan might be the more apt term — towards a comprehensive account of the science fiction genre’s Radium Age (1900–1935). These notes are very rough-and-ready, and not properly attributed in many cases. More information on Josh’s ongoing efforts here and here.

RADIUM AGE TIMELINE: [1900 | 1901 | 1902 | 1903] | 1904 | 1905 | 1906 | 1907 | 1908 | 1909 | 1910 | 1911 | 1912 | 1913 | 1914 | 1915 | 1916 | 1917 | 1918 | 1919 | 1920 | 1921 | 1922 | 1923 | 1924 | 1925 | 1926 | 1927 | 1928 | 1929 | 1930 | 1931 | 1932 | 1933 | [1934 | 1935]. (The brackets, here, indicate “interregnum” years — i.e., periods of overlap between sf’s Radium Age and its Scientific Romance and so-called Golden Age eras.)

Proto-sf coinages dating to 1922, according to the Historical Dictionary of Science Fiction: EARTH PERSON

- Karel Čapek’s Továrna na absolutno (The Absolute at Large, 1922; in English, 1927). In the near future, a Czech scientist invents “perfect combustion,” and an industrial concern starts manufacturing an atomic reactor that provides cheap energy — with an unexpected byproduct: the Absolute, the spiritual essence that permeates every particle of matter… or did, anyway, until matter began to be annihilated by the super-efficient Karburetor. As they’re released from imprisoning matter by efficient Karburetors and Molecular Disintegration Dynamos cranked out in the thousands by Ford Motors (the novel’s Czech title means “the factory of the Absolute”) and other manufacturers around the world, God-particles infect humankind with wonder-working powers and ecstatic religious sentiments. What’s more, the Absolute begins operating factories itself, producing far too many finished goods for anyone to consume. As a result, economies collapse, unemployment is universal, and fanatical sects whose -isms (including rationalism, nationalism, and sentimentalism) are religious only in the broadest sense do battle. Every country is drawn into the Greatest War, during which atomic weapons are deployed and civilization collapses.

- Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage (1922). When war breaks out in Europe, British civilization collapses overnight. The ironically named protagonist must learn to survive by his wits in a new Britain. When we first meet Savage, he is a complacent civil servant, primarily concerned with romancing his girlfriend. During the brief war, in which both sides use population displacement as a terrible strategic weapon, Savage must battle his fellow countrymen. He shacks up with an ignorant young woman in a forest hut — a kind of inverse Garden of Eden, where no one is happy. Eventually, he sets off in search of other survivors… only to discover a primitive society where science and technology have come to be regarded with superstitious awe and terror. Fun fact: Cicely Hamilton was an Anglo-Irish novelist, dramatist, and campaigner for women’s rights who served during WWI with an ambulance unit and at a military hospital in France. Her 1909 treatise Marriage as a Trade is a witty criticism of that institution. Serialized and reissued by HILOBROW. Note that although “future war” proto-sf flourished from c. 1870-1914, WWI caused a hiatus. This book, along with Edward Shanks’s The People of the Ruins (1920), marks a return of sorts to the subgenre, though now with much less excitement and more foreboding. Reissued by MIT Press’s RADIUM AGE series.

- Alexander Moszkowski’s Die Inseln der Weisheit (The Isles of Wisdom). Reputed to be the most rigorous and thorough of all utopian satires; frequently very funny. Features expeditions to various utopian and dystopian islands that embody social-political ideas of European philosophy and extrapolates them for their absurdities when they are put into practice. The novel’s “island of technology” (Sarragalla) anticipates mobile telephones and a thorough mechanization of life.

- Arthur Conan Doyle’s “The Leather Funnel.” “This really will be an exceedingly interesting experiment. You are yourself a psychic subject — with nerves which respond readily to any impression.” An occult story, really — not proto-sf.

- Achmed Abdullah’s Alien Souls. A collection of ethnographic fiction; fifteen stories set in the Near East. All have good characterization and local color, but there is usually only a hint of the fantastic, often involving reincarnation and fate.

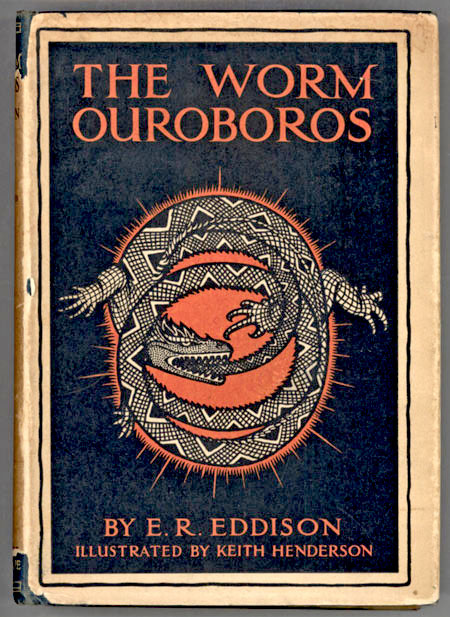

- E.R. Eddison’s The Worm Ouroboros. On the planet Mercury — essentially, a fantasy version of Earth — the Lords of Demonland (the brothers Juss, Spitfire, and Goldry Bluszco, and their cousin Brandoch Daha) are at war with King Gorice of Witchland, who demands that Demonland recognize him as overlord. Juss and his brothers reply that they and all of Demonland will submit if the king (a famous wrestler) can defeat Goldry Bluszco in a wrestling match; Gorice is killed. Gorice’s successor, a wizard, banishes Goldry to an enchanted mountain prison. Lord Spitfire is sent back to raise an army out of Demonland, while Lord Juss and Brandoch Daha, aided by King Gaslark of Goblinland, attempt an assault on Carcë, the capital of the Witches, where they think Goldry is held. Juss and Brandoch Daha are captured — will La Fireez, the prince of Pixyland, come to their aid? Many more adventures lie ahead… but when the exploits and battles are over, everything returns to exactly the way it was. Fun facts: J.R.R. Tolkien and C.S. Lewis were fans of Eddison’s novel — the title of which refers to the Norse myth of a dragon swallowing its own tail. Like the worm Ouroboros, Eddison’s tale ends where it begins.

- Coutts Brisbane’s “The Almighty Atom.” About atomic disintegration.

- The Man from Beyond is a 1922 American silent mystery film starring Harry Houdini as a man found frozen in arctic ice who is brought back to life. When he returns to life, Dr. Sinclair does not tell Howard that he is 100 years behind the times, planning to study his reactions after they return to civilization. Howard tells that he loved Felice, the daughter of the captain of a ship, and there was a mutiny. In his last memory of the event, Howard was trying to save the young woman’s father when he received a blow to the head. Dr. Sinclair persuades Howard not to search the snow and ice of the arctic, but to return to civilization. When Dr. Sinclair returns home, he learns that his ward’s father, Dr. Crawford Strange, had set out to join him in the arctic but was lost. It is the wedding day of his ward. When Howard sees the bride, he calls out to her, calling her “Felice” and begging her to recall their love. The ward’s name is Felice Strange (Connelly) and she is the reincarnation of Howard’s lost sweetheart.

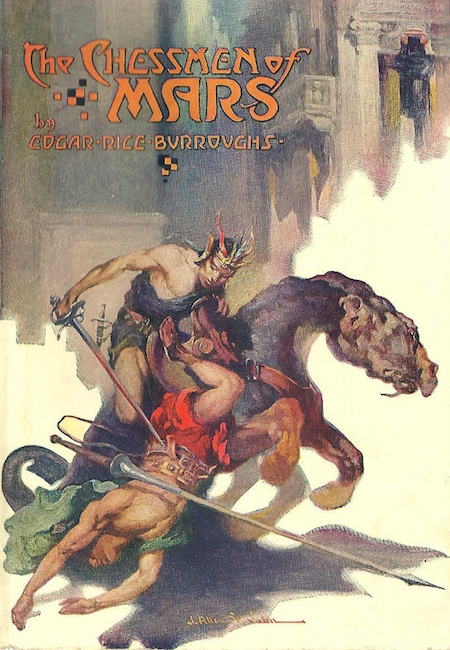

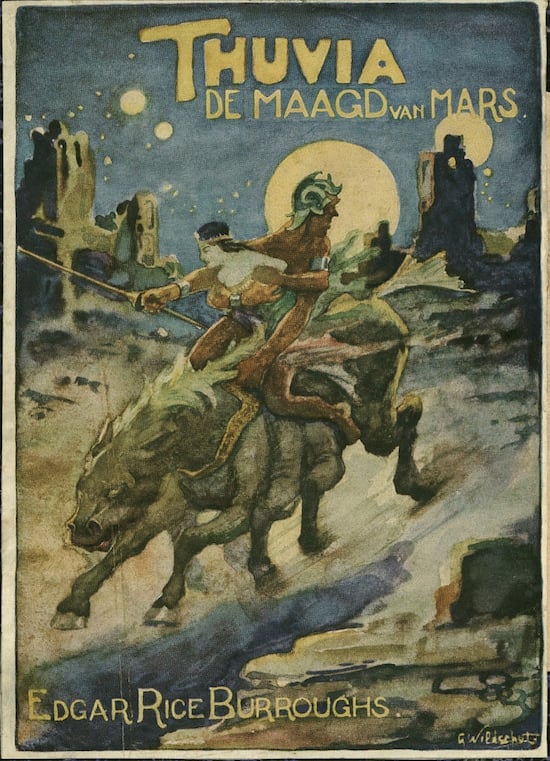

- Edgar Rice Burroughs‘s The Chessmen of Mars. Gahan, king of a small but prosperous Martian city-state, attempts to woo Tara, the spirited daughter of Earth’s John Carter… but she rebuffs him, because he’s un-manly. When Tara’s flier is lost in a Barsoomian storm, Gahan heads out to rescue her. The two are captured by the Kaldanes — super-evolved, emotionless brain-creatures who live in a symbiotic relationship with headless “rykors” — only to be befriended by Ghek, a Kaldane who has reconnected with his emotions… and who proves a fascinating and amusing companion who accompanies them for the remainder of their odyssey. The three wanderers are then captured by the hordes of Manator, who play jetan — a chess-like game in which men fight to the death for possession of the gameboard’s squares. Gahan’s successful battles — and strategic moves — demonstrate his worth to Tara. Fun facts: This is the fifth of Burroughs’s eleven John Carter novels; many readers consider it one of the best installments in the series. The Chessmen of Mars first appeared in serial form in Argosy All Story Weekly in 1922. An excerpt is collected in From Wells to Heinlein (1979, ed. James Gunn).

- Ada Barnett’s The Man on the Other Side. See this list of Pre-1950 Utopias and Science Fiction by Women.

- Isabel Griffiths’s Three Worlds. See this list of Pre-1950 Utopias and Science Fiction by Women.

- Martha Cabanné Kayser’s The Aerial Flight to the Realm of Peace. See this list of Pre-1950 Utopias and Science Fiction by Women.

- Jessie Douglas Kerruish’s The Undying Monster: A Tale of the Fifth Dimension. See this list of Pre-1950 Utopias and Science Fiction by Women.

- Ella Scrysmour’s The Perfect World: A Romance of Strange People and Strange Places. Most likelt two separate magazine novels here published together as a “fixup.” In the first main sequence the two young male protagonists are transported from a company town dominated by their family’s coal mine into an underground cave system where a lost race of dwarf Israelites — exiled after an Old Testament quarrel — has lived for 3000 years and grown horns. After the men emerge in Australia, after missing World War One, and noting that the End of the World is nigh, they escape in the nick of time with their uncle — who is responsible for the invention of a space-ready airship — to Jupiter, where another oligarchy, this time pre-Adamic, subjects the main protagonist — as had happened already underground — to erotic inducements. He marries a princess and together they rule Jupiter in peace. In dealing with the sinlessness of the Jovians, “Scrysmour ineffectively prefigured the work of C S Lewis” (according to the SFE).

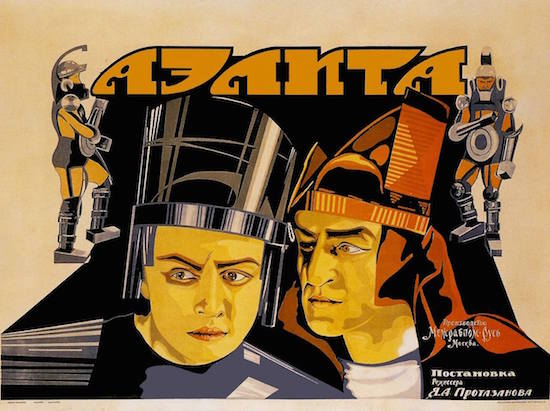

- Aleksey Tolstoy’s Aelita (serialized 1922–1923). After the Russian Civil War (1918–1920), a lonely Soviet engineer, Mstislav Los’, and a retired soldier, Alexei Gusev, travel to Mars in a rocketship. It seems that Earthmen have been there before: the Martians they encounter are the descendants of Mars natives and Atlanteans! The class divide between workers — who live underground, near their machines — and the ruling class (the Engineers) is severe. Worse, the planet faces environmental catastrophe; the Engineers’ (Jor-El-esque) leader, Toscoob, plans to destroy their city, in order to save the planet. While Gusev helps lead a worker uprising against the Engineers, Los’ — who has fallen in love with Toscoob’s daughter Aelita, the princess of Mars — works to help her father crush the rebellion. First published as a three-part serial in Red Virgin Soil, from November/December 1922 through March/April 1923. Fun fact: Aleksey Tolstoy is credited with having produced some of the earliest works of Russian science fiction. Aelita was adapted, in 1924, as a far-out silent film directed by Yakov Protazanov, the first Russian sf film. Film released in the U.S. as Aelita: The Queen of Mars or War of the Robots.

- Ilya Ehrenburg’s Istoriya neobychainykh pokhozhdenii Khulio Khurenito i ego druzei (The Fantastic Adventures of Julio Jurenito and his Friends). Depicts a future war conducted with ultimate “atomic” weapons. Ehrenburg was among the most prolific and notable authors of the Soviet Union; he published around one hundred titles. He became known first and foremost as a novelist and a journalist – in particular, as a reporter in three wars (First World War, Spanish Civil War, Second World War). His incendiary articles calling for vengeance against the German enemy during the Great Patriotic War won him a huge following among front-line Soviet soldiers.

- James Barr’s “The World of the Vanishing Point.” A microscopic adventure — Ashley singles it out.

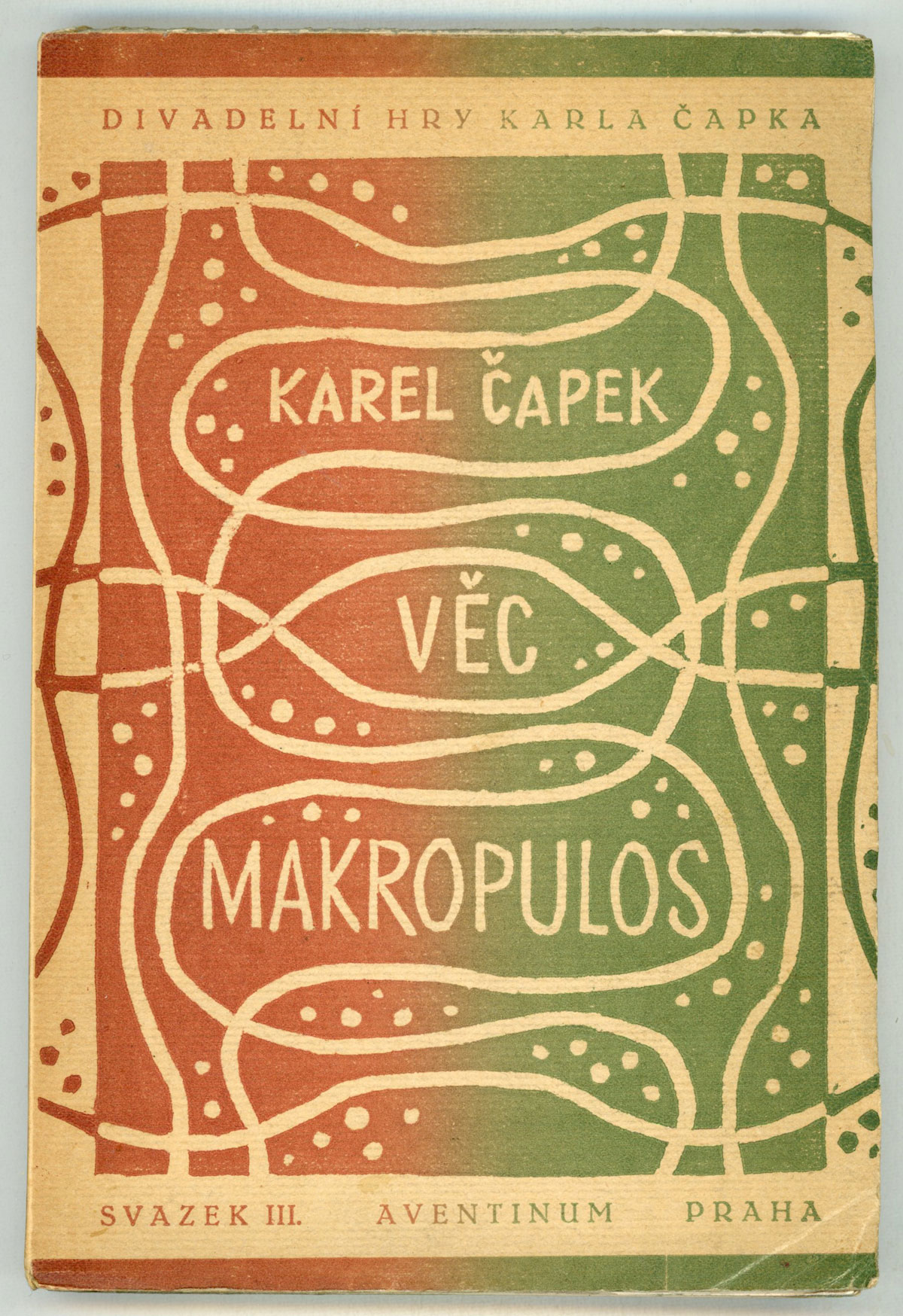

- Karel Čapek’s Vec Makropulos; komedie o třech dějstvích s přeměnou. Čapek’s play explores the theme of immortality by depicting a woman who may have used an elixir of life.

- Philip M. Fisher’s “Worlds Within Worlds” (13 May 1922 Argosy). Various vibrational frequencies mark the difference between coexistent parallel worlds. Also seeks to describe an advanced utopia.

- Harrington Hext (Eden Phillpotts)’s Number 87. Scientist discovers “number 87,” a powerful energy source, and embarks on a campaign of terror as an international anarchist killing rival scientists, various dictators, and other heads of state with explosive projectiles. “Stodgy and slow-moving at first, but it comes to life once the story leaves the Eccentric Club.” – Bleiler

- Rodolfo Teófilo’s O Reino de Kiato (No país da verdade) [“The Kingdom of Kiato (In the Country of Truth)”] (1922) by Rodolfo Teófilo (1853-1932), an island-based rational society with overt eugenics elements

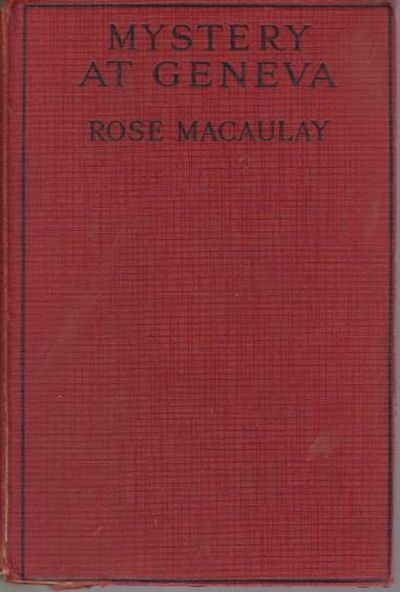

- Rose Macaulay’s Mystery at Geneva: An Improbable Tale of Singular Happenings. Set in an undefined near future where a monarchist counter-revolution has replaced the Bolsheviks in Russia and a reporter (a woman in drag) helps save the League of Nations from a conspiracy designed to restore communism.

- Vivian Itin’s Strana Gonguri [“Gonguri Land”] Although Krasnaya zvezda is often considered the earliest book of authentically Soviet sf, the first post-revolutionary work was Vivian Itin’s utopia Strana Gonguri [“Gonguri Land”] (1922). This went almost unnoticed, overshadowed by the success the same year of the interplanetary romance Aelita (1922; trans 1957) by Alexei Tolstoy. This landmark of early Soviet sf, inspired by Edgar Rice Burroughs, tells of a Russian engineer and a Martian beauty involved in a Marxist revolution.

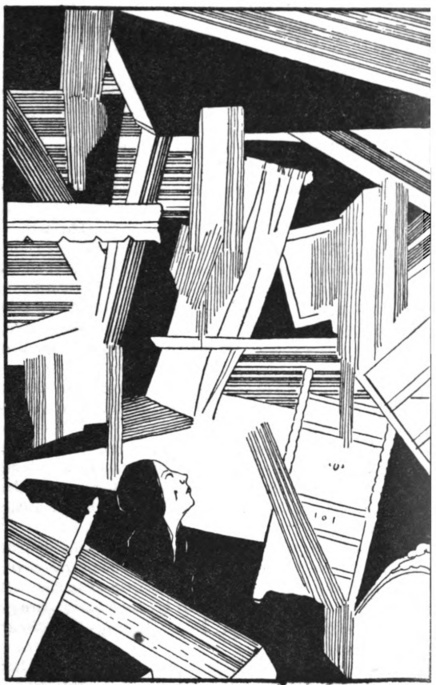

- May Sinclair’s “Where Their Fire Is Not Quenched.” Adventures in the fourth dimension. “Then, suddenly, the room began to come apart before her eyes, to split into shafts of floor and furniture and ceiling that shifted and were thrown by their commotion into different planes. They leaned slanting at every possible angle; they crossed and overlaid each other with a transparent mingling of dislocated perspectives, like reflections fallen on an interior seen behind glass.”

- E. Charles Vivian’s City of Wonder. The author’s first lost race novel. After hearing a remarkable story, the hero and his two companions journey to discover a lost land in the South Pacific that is the last outpost of Lemurian descendants in the city of Kir-Asa. The city is guarded by gigantic apes under the command of women, who are also the rulers of the city.

- J.-H. Rosny aîné’s L’Étonnant Voyage d’Hareton Ironcastle (The Amazing Journey of Hareton Ironcastle). Explorers eventually discover a fragment of an alien world, with its fauna and flora, attached to Earth. The novel was adapted and retold by Philip José Farmer.

- A.E.’s The Interpreters. George William Russell (1867 – 1935), who wrote with the pseudonym Æ (often written AE or A.E.), was an Irish writer, editor, critic, poet, painter and Irish nationalist. In 1886 he and William Butler Yeats helped found the Dublin Lodge of the Theosophical Society and much of his work reflects a mystical agenda. Set in a great city in the indeterminate future just as a long-lived Pax Aeronautica dissolves into factional warfare involving great airships; those captured in this schism then engage in philosophical debates. Also see AE’s novel The Avatars (1932).

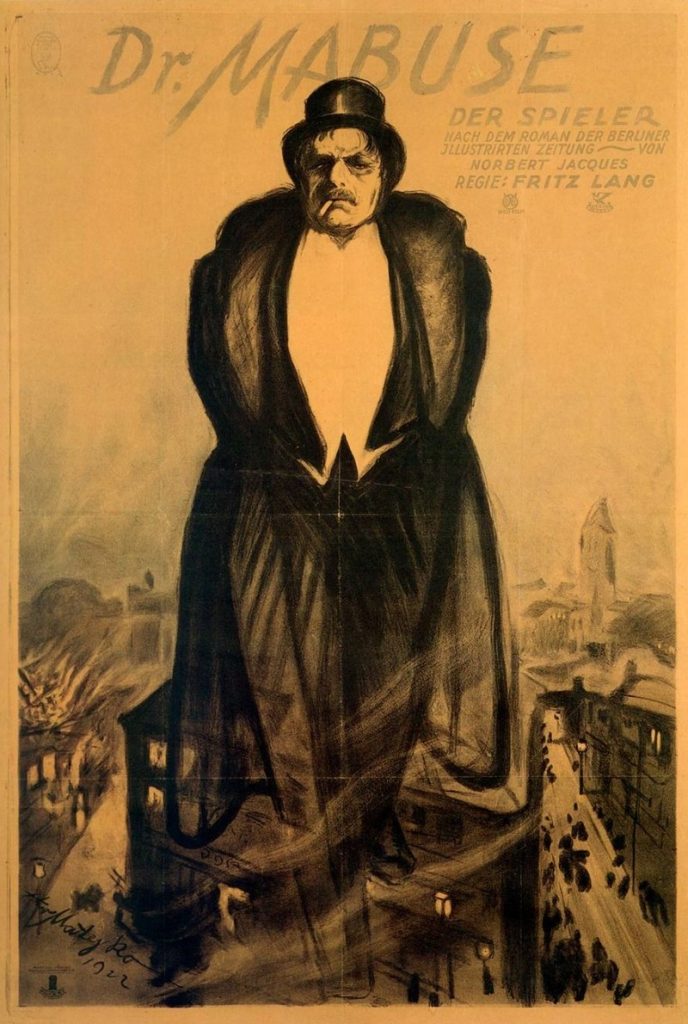

- Dr. Mabuse the Gamblers the first film in the series about the character Doctor Mabuse who featured in the novels of Norbert Jacques. It was directed by Fritz Lang and released in 1922. The film is silent and would be followed by the sound sequels The Testament of Dr. Mabuse (1933) and The Thousand Eyes of Dr. Mabuse (1960). Dr. Mabuse is a criminal mastermind, doctor of psychology, and master of disguise, armed with the powers of hypnosis and mind control, who oversees the counterfeiting and gambling rackets of the Berlin underworld. He visits gambling dens by night under various guises and aliases, using the power of suggestion to win at cards and finance his plans.

Man Ray made his “rayographs” without a camera by placing objects directly on a sheet of photosensitized paper and exposing it to light. Man Ray had photographed everyday objects before, but these unique, visionary images immediately put the photographer on par with the avant-garde painters of the day. Hovering between the abstract and the representational, the rayographs revealed a new way of seeing that delighted the Dadaist poets who championed his work, and that pointed the way to the dreamlike visions of the Surrealist writers and painters who followed.

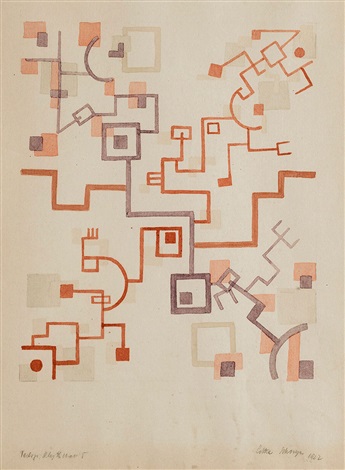

Netzwerk oder Geflecht (1922)

Georgia O’Keeffe’s Lightning at Sea (1922). One of a group of maritime paintings and pastels inspired by the artist’s 1922 visit to Maine. While many of these works are dominated by curving organic shapes, “Lightning at Sea” is unusually angular and schematic in its composition. The hard-edged linear quality of the lightning bolt and the sun rays at its center demonstrates O’Keeffe’s awareness, of and willingness to experiment with, modernist styles that were more geometric in nature.

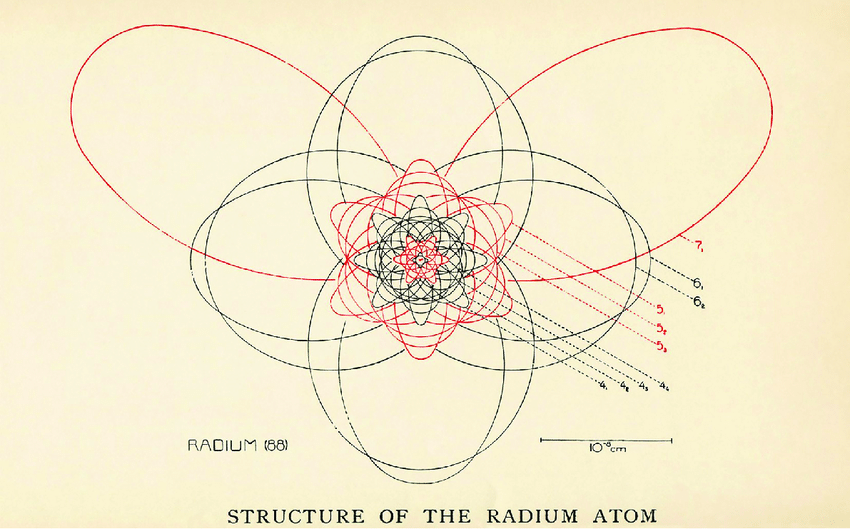

ALSO: Bohr wins Nobel for investigations into atomic structure and radiation. H. J. Muller sets out the basic properties of genetic heredity. The world’s first regular wireless broadcasts for entertainment begin transmission from a hut at the Marconi Company laboratories in England. Vitamins D and E discovered. Malinowski’s influential ethnological text Argonauts of the Western Pacific. First publication of Ludwig Wittgenstein’s Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus in an English translation. Irish Free State proclaimed, Mussolini forms Fascist government; new KKK gains political power in US. Eliot’s “The Waste Land,” Joyce’s Ulysses, O’Neill’s The Hairy Ape. Sabatini’s Captain Blood: His Odyssey. Erskine Childers, author of The Riddle of the Sands, executed. Carnap seeks to provide a logical basis for a theory of space and time in physics in his doctoral thesis Der Raum (Space). Weber’s “Methodology of the Social Sciences.” Carnarvon and Carter discover King Tut’s tomb. Murnau’s Nosferatu. Marie Stopes advocates birth control in England.

David Daiches’ The Present Age After 1920 has the following to say about British poetry of the 1920s. The era saw a “revolution” the result of which was

the ousting of the view of poetry represented by Palgrave’s Golden Treasury in favour of a poetic practice and a critical theory which exalted cerebral complexity, allusive suggestion, and precision of the individual image. The poet was no longer the sweet singer whose function was to render — in mellifluous verse and a more or less conventional romantic imagery a self-indulged personal emotion, he was the explorer of experience who used language in

order to build up rich patterns of meaning which, however impressive their immediate impact, required repeated close attention before they communicated themselves fully to the reader. A core of burning paradox was preferred to a gloss of surface beauty. It was not the function of poetry to pander to the languid dreams of a pampered sensibility, to revel in the sweetness of a cultivated nostalgia or the sad plangency of controlled self-pity. Tennyson’s ‘Break, break, break’ and Arnold’s ‘Dover Beach’ show, in yery different ways, how Victorian poetry always tended to run to elegy. Eliot’s The Waste Land, published in 1922, was worlds apart from that skilful alternation of worry and elegy which constituted Tennyson’s In Memoriam. Complex, allusive, drawing on a great variety of both occidental and oriental myth and symbol, using abrupt contrasts and shifting counter-suggestions to help unfold the meaning, eliminating all conjunctive phrases or overt statements that might indicate the relation of one scene or situation to another, The Waste Land was both a demonstration and a manifesto of what the new poetry wanted to do and could do.

Dada had been launched 1916. Totally rejecting the society and values they held responsible for the horrors of WWI. It set itself up against reason and rationalism, against bourgeois society and culture. As Tzara noted in his 1922 “Lecture on Dada,” “We have had enough of the intelligent movements that have stretched beyond measure our credulity in the benefits of science. What we want now is spontaneity.”

In a 1922 letter, Mondrian insists that his abstract “Neoplastic” work “is purely a theosophical art.” Although affected by Cubism, Mondrian’s thinking predated his encounter with Cubism, and is ultimately rooted in esoteric doctrines of mathematics. Mondrian was painting semiotic graphs — attempting to express general, not specific, truths.

MORE RADIUM AGE SCI FI ON HILOBROW: HiLoBooks homepage! | What is Radium Age science fiction? |Radium Age 100: 100 Best Science Fiction Novels from 1904–33 | Radium Age Supermen | Radium Age Robots | Radium Age Apocalypses | Radium Age Telepaths | Radium Age Eco-Catastrophes | Radium Age Cover Art (1) | SF’s Best Year Ever: 1912 | Radium Age Science Fiction Poetry | Enter Highbrowism | Bathybius! Primordial ooze in Radium Age sf | War and Peace Games (H.G. Wells’s training manuals for supermen) | Radium Age: Context series | J.D. Beresford | Algernon Blackwood | Edgar Rice Burroughs | Karel Čapek | Buster Crabbe | August Derleth | Arthur Conan Doyle | Hugo Gernsback | Charlotte Perkins Gilman | Cicely Hamilton | Hermann Hesse | William Hope Hodgson | Aldous Huxley | Inez Haynes Irwin | Alfred Jarry | Jack Kirby (Radium Age sf’s influence on) | Murray Leinster | Gustave Le Rouge | Gaston Leroux | David Lindsay | Jack London | H.P. Lovecraft | A. Merritt | Maureen O’Sullivan | Sax Rohmer | Paul Scheerbart | Upton Sinclair | Clark Ashton Smith | E.E. “Doc” Smith | Olaf Stapledon | John Taine | H.G. Wells | Jack Williamson | Stanisław Ignacy Witkiewicz | S. Fowler Wright | Philip Gordon Wylie | Yevgeny Zamyatin